11.1 Introduction

Today, more than half of the world’s population lives in urban areas. While cities are projected to continue to grow, they are currently not equipped to accommodate such large populations when faced with rapid urbanization. This rapid urbanization and growth are resulting in greater socioeconomic inequities, air pollution, overcrowding, displacement and overburdened infrastructure, particularly in developing countries (Reference Eckert and KohlerEckert & Kohler, 2014; Reference PatilPatil, 2014). Sustainable Development Goal 11 (SDG11), titled “Sustainable cities and communities”, comes at a critical time to promote and develop cities that are inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable. With a multisectoral urban governance approach that emphasizes health, cities can expand successfully and equitably while leaving no residents behind.

This chapter provides an overview of the current struggles experienced by cities, and how urban governance driven by health equity can play a critical role in avoiding rapid and unequal urbanization. Our approach recognizes health as an outcome of, and a precursor to, sustainable cities. However, our reliance on the urban governance framework and our commitment to a health equity lens will favour our interpretation of SDG11 towards one where urban planning changes must be implemented to see a resulting change in health and health equity (Reference 214Borrell, Pons-Vigués and MorrisonBorrell et al., 2013). This chapter will also provide a causal pathway that models the relationship between SDG11 (sustainable cities and communities) and SDG3 (good health and wellbeing) within the context of the other SDGs. For example, the causal pathway will show that SDG2 (zero hunger) mediates the relationship between SDG11 and SDG3 because access to food is influenced by the urban environment and ultimately impacts people’s health. The causal pathway described will show bidirectional arrows due to the complex nature of the interactions. To demonstrate these relationships, we will provide examples of interventions that have been implemented through a multisectoral approach, using urban planning strategies to impact health.

First, the Youth at a Healthy Weight (JOGG) initiative in the Netherlands is a public–private partnership that uses urban planning principles to promote healthy lifestyles for children in municipalities across the Netherlands (JOGG-Aanpak, n.d.). As a response to projections for rising overweight and obesity in the Netherlands, JOGG has grown into a national intervention that has now been implemented in over half of the Netherlands’ 352 municipalities. The goal of the intervention is to promote healthy weight in the Netherlands to prevent illness and social costs associated with overweight and obesity. Second, the Barcelona Superblocks in Spain is a large-scale multisectoral initiative that aims to improve public spaces, promote more sustainable mobility, and increase urban green spaces (Reference Palència, León-Gómez and BartollPalència et al., 2020; Reference RuedaRueda, 2016). Through such programmes, the goal is to address Barcelona’s high air pollution levels, reduce noise exposure and traffic injuries, and improve health, culture and economic gains.

Both programmes provide insight on the intersections between urban governance and health system governance and examine their population-health impacts. We use the term urban governance, defined as the political power exercised over the physical and social environments within diverse settings and across unequal contexts (Reference 214Borrell, Pons-Vigués and MorrisonBorrell et al., 2013). We refer to health systems as the network of public and private institutions that promote health as a primary goal of its function (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2017). Using this definition and focus on urban areas, we use the term health system governance to refer to city-level health systems’ power over the physical and social environment within diverse settings and across unequal contexts. Although some of this power may be governed by a national-level health system, implementation of policies and programmes can still differ across cities (WHO, 1991). While both of our main case studies come from high-income settings in Europe, these are strong cases that address some of the consequences of rapid urbanization and provide insight on opportunities that urban health system governance can achieve in developing healthy, sustainable, inclusive and resilient cities.

11.2 Background

As cities continue to grow, it is expected that by 2030, more than 60% of the world’s population will be living within an urban area (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2018). The focus is now on how current physical and social environments can accommodate this expanding population. To add to the complexities of overcrowding in many urban areas worldwide, growing socioeconomic inequities will result in a new set of challenges. In particular, cities experiencing fast growth rates have adjusted through rapid urbanization, resulting in swift actions that tend to leave marginalized populations behind. For example, due to a lack of affordable housing, there has been an increase in slum dwellings, and as a result of older infrastructure, water and sanitation systems have been overburdened, resulting in greater periods of shut-offs and sewage-related complications (United Nations, n.d.-b). Furthermore, this unplanned urban sprawl has contributed to greater traffic, directly impacting air and noise pollution in many cities (United Nations, n.d.-a). In 2016, it was estimated that air pollution had caused 4.2 million premature deaths (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, n.d.).

The disciplines of urban planning and health have long been interconnected (Reference Kochtitzky, Frumkin and RodriguezKochtitzky et al., 2006). Public health and urban planning collaborations date back to the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries when the first wave of migration to cities occurred as a result of growing industrial cities in places like the United Kingdom and the United States (Reference BartonBarton, 2005; Reference Northridge and FreemanNorthridge & Freeman, 2011). With this growth, issues of overcrowding and unsanitary conditions began to rise and both sectors came together to address them through more adequate housing and the development of sewage systems. However, as city funding decreased post-industrialization, urban planning became a profitable sector through private development, and public health turned to issues of contagion. Today, the effects of dissociation have become evident with growing evidence of health inequities in cities worldwide. Place-based research has shown the inequities in accessing resources including health, food and social services, primarily in low-income neighbourhoods. These same neighbourhoods are associated with poorer health and life opportunities including education and employment (Reference Ross and MirowskyRoss & Mirowsky, 2001).

SDG11, sustainable cities and communities, comes at a critical time as it recognizes the challenges faced by rapid urbanization. The United Nations outlines seven targets to better grasp the scope of SDG11 and focus action on the greatest needs. The targets include goals to 1) provide everyone access to an affordable home and basic services, 2) ensure access to affordable transportation, 3) improve urban planning in every country, 4) conserve cultural and natural heritage, 5) reduce deaths by improving disaster responses, 6) reduce the adverse environmental impact of cities, and 7) ensure access to public green space (United Nations, n.d.-a). Investments in infrastructure, public transportation and green spaces can have tremendous benefits for economic activity, climate change and ultimately the health and wellbeing of residents. By developing sustainable cities and communities, we provide opportunities for healthy cities to flourish where they can engage residents and policymakers to address inequities and promote health and wellbeing. Therefore, urban health systems have a critical role to lead, promote and implement good governance and leadership for cities to achieve health and wellbeing.

11.3 Causal pathways

Our framework to identify health policy co-benefits between SDG3 and SDG11 draws on the framework for urban governance outlined by Reference 214Borrell, Pons-Vigués and MorrisonBorrell and colleagues (2013). As shown in Fig. 11.1, health system governance in urban areas influences the urban physical and social environment by providing or influencing the infrastructure needed to perform medical interventions, encourage healthy behaviours, and improve resource access (WHO, 1991). For instance, the health system may combine urban planning, the natural environment and environmental characteristics to create green spaces that help reduce the health impacts of air pollution while creating opportunities for residents to exercise, play and relax. However, health system intervention in the urban environment is not always equitable. It may result in inequities in access to resources and medical care, across social class, race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, ability and age dimensions. For example, while health systems may determine the location of health care facilities throughout a city, without adequate public transportation, some residents, particularly those with no access to private vehicles, may not be able to access those services. Urban inequities lead to population health inequities and exacerbate population health needs, which therefore influence and dictate how health systems should govern the urban environment. These inequities are attributed to historical and contemporary policies that result in the segregation of residents based on social class, race and ethnicity (Reference DwyerDwyer, 2010; Reference Taeuber and TaeuberTaeuber & Taeuber, 2009). Segregated areas are then more susceptible to disinvestment and lack of resources that directly impact the health of residents (Reference Acevedo-Garcia, Lochner, Kawachi and BerkmanAcevedo-Garcia & Lochner, 2003). For instance, many cities failed to equitably distribute the COVID-19 vaccine, resulting in population health needs specific to certain groups (Reference DiRago, Li and TomDiRago et al., 2022). Box 11.1 describes the example of Chicago.

Fig. 11.1 Urban health system governance and Sustainable Development Goal co-benefits

In cities where COVID-19 vaccines have become available, vaccine distribution has been inequitable, contributing to unequal COVID-19 infections, hospitalizations and deaths. The Chicago Health Department collected in-depth data on COVID-19 infections, hospitalizations and deaths by race throughout the pandemic and it demonstrates the inequity in vaccination. In the earliest stages of COVID-19 vaccine rollout in Chicago, vaccines were disproportionately administered to White Chicagoans. Even though 33% of Chicago residents are White and 59% are Black or Latinx, in the first week of vaccine rollout over 65% of the vaccines were administered to White Chicagoans compared to 18% for Black and Latinx Chicagoans (Chicago Department of Public Health, n.d.). As of 25 June 2021, in Chicago, six months after the first doses were administered, inequities still persisted as 38% of the Black population and 46% of the Latinx population had received at least one dose of the vaccine compared to 61% of the White population (Chicago Department of Public Health, n.d.).

Inequitable vaccination translated to inequitable health impacts (Reference Zeng, Pelzer and GibbonsZeng et al., 2021). The June 25th Reopening Metrics Update showed that Black and Latinx Chicagoans represented a far larger portion of COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations and deaths, compared to White and Asian Chicagoans. Black and Latinx Chicagoans were represented in about 75% of COVID-19 cases from 19 June to 25 June 2021, greater than three out of every four COVID-19 hospitalizations from 1 June to 25 June, and greater than three of every four COVID-19 deaths in the city of Chicago from 1 May to 22 June 2021 (Chicago Department of Public Health, 2021). These massive racial gaps in COVID-19 health outcomes should indicate to Chicago health authorities the need to prioritize reaching the Black and Latinx populations in COVID-19 interventions moving forward.

There is a strong relationship between SDG3 and SDG11, as health system governance in urban areas is linked to the urban planning and public policy sectors. Population health is directly and indirectly impacted by physical and social factors like city infrastructure, land costs, property taxes, transportation and housing. Providing health services in a sustainable city requires a built environment that includes buildings to house health services and community amenities like food outlets and green spaces to promote public health. Health services practitioners have outlined that the provision of health services should involve an accessible location; design principles that create a patient-friendly, healing, spacious, clean, flexible and accommodating environment; and amenities located in the surrounding environment that provide food, shopping, internet access and childcare services (Reference LuxonLuxon, 2015). The principle of accessibility is especially important for promoting urban health equity. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, people with mobility and cognitive impairments saw impacts on their caregiving and more barriers in accessing care owing to limited accommodating public policies (Reference BaumerBaumer, 2021; Reference 216Landes, Turk and FormicaLandes et al., 2020; Reference 218Turk, Landes and FormicaTurk et al., 2020). Furthermore, social distancing policies resulted in disruptions in care and isolation, while lack of utilities including water and electricity made it difficult for many to stay at home (Reference 217Pineda and CorburnPineda & Corburn, 2020).

As health systems alter physical and social environments in urban areas, they will influence other SDGs. For instance, a health system that prioritizes green space to give city residents an outdoor space for exercise, games and sports will produce co-benefits for SDG15 (Life on land) by providing a place for plants and animals to live and grow. Health system governance in urban areas can also have a co-benefit with SDG1 (no poverty), SDG2 (zero hunger), SDG4 (quality education) and SDG8 (decent work and economic growth) by stimulating economic activity and investment. For example, hospitals can serve as important “anchor institutions” that contribute to the vitality of the surrounding urban area (Reference SchwartzSchwartz, 2017). Globally, about 60 per 10 000 people are medical doctors or nurses (WHO, 2021). In the United States, the country that spends the most on health care, the health care sector employs about one in eight jobs (KFF, 2021). Additional jobs are supported indirectly, through purchase of goods and services from other businesses (American Hospital Association, 2017).

In addition, the health care sectors of wealthier countries are beginning to address social needs arising from health inequities associated with the physical and social environments in growing urban areas. In the United Kingdom, a model known as “social prescribing” links patients of primary care physicians to social and community services to improve health, wellbeing and social connection (Reference Bickerdike, Booth and WilsonBickerdike et al., 2017). Interventions typically involve link workers, who connect patients to resources such as housing, welfare and budgeting, education and literacy, peer networks, counselling, exercise activities, outdoor recreation, gardening and others (Reference Tierney, Wong and RobertsTierney et al., 2020). For example, Life Rooms, a social prescribing intervention for people with mental illness who reside in disadvantaged communities in Liverpool and Sefton (UK), connects patients with learning opportunities and financial counselling (Reference Hassan, Giebel and MorasaeHassan et al., 2020). In the United States, non-profit hospitals are required to perform community investment in order to maintain their tax-exempt status. As a result, a growing number of hospitals are implementing interventions that reconstruct and influence the physical and social environments and opportunities surrounding patients, including creating affordable housing, promoting nutritious food access, expanding transportation options, enhancing local education, and constructing community facilities (Reference Horwitz, Chang and ArcillaHorwitz et al., 2020; Reference Koeman and MehdipanahKoeman & Mehdipanah, 2021; Reference SchwartzSchwartz, 2017).

However, we return to equity as a key priority for health systems, since a health system’s outreach and intervention within an area may have the unintended consequence of contributing towards gentrification in cities by increasing property values and “pricing out” the surrounding community (Box 11.2) (Reference Cole, Mehdipanah and GullónCole et al., 2021). Academic scholarship has debated the comparative strength and influence of the public and private sectors in the health system and their potential impacts on urban health equity. Research has suggested that health systems with a greater reliance on the private sector may place less emphasis on equity, public health and primary care and will be less coordinated than those with a greater reliance on the public sector (Reference Basu, Andrews and KishoreBasu et al., 2012). This is evident in a growing body of research that discusses health care gentrification where for-profit health care systems favour wealthier residents by situating themselves in higher-income areas, including areas recently gentrified, to improve profit returns as opposed to reducing health care inequalities (Reference Dahrouge, Hogg and MuggahDahrouge et al., 2018; Reference Martínez, Smith and Llop-GironésMartínez et al., 2016; Reference Sumah, Baatiema and AbimbolaSumah, Baatiema & Abimbola, 2016). Regardless of whether the public or private sector is dominant, more investment in policies and regulations focusing on zoning and land development are needed to promote health across the whole city and improve the sustainability of the urban health system (Reference Elsey, Agyepong and HuqueElsey et al., 2019).

In Amman, Jordan, the development of two hospitals highlights the detrimental consequences for urban areas that can occur when little coordination goes into the development of a private hospital. Jordan Hospital is a 247-bed hospital that was initiated in 1996 and Khalidi Hospital is a 160-bed hospital that was initiated in 1978. At the time that these hospitals were built, private hospitals were subject to very few requirements and regulations regarding city planning and the locations of the hospitals were largely subject to the population’s medical needs and city’s circumstances. Private hospitals saw an opportunity for profit owing to the location and health services demand, city laws allowed for an easy change from residential to commercial zoning, and no city-wide planning went into the development of these two hospitals. As a result, the introduction of these two private hospitals increased land prices and dramatically changed the composition of the surrounding area, increasing the number of commercial and medical buildings while decreasing the number of residential buildings including affordable housing. The changes also resulted in more traffic jams and little space for parking in the areas surrounding the two hospitals (Reference Irmeili and SharafIrmeili & Sharaf, 2017).

11.4 Case study 1: Youth at a Healthy Weight (JOGG) initiative in Dutch cities

Our first case study describes the Youth at a Healthy Weight (Jongeren op Gezond Gewicht – JOGG) intervention in the Netherlands. JOGG is a national organization with ANBI status (non-profit) that promotes public–private partnership between the Netherlands Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport, local municipalities and private partners to improve healthy living for youth in the Netherlands by altering the urban physical and social environments. The focus on the environment surrounding youth mirrors the EPODE approach, a methodology established in France and in use in similar projects in six European countries (Reference Borys, Le Bodo and JebbBorys et al., 2012). JOGG was established in 2014 out of the efforts of the Healthy Weight Covenant and has since cultivated a diverse network of partners that now includes the Netherlands Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport, over 180 municipalities and nearly 40 other organizations (Reference Collard, Slot-Heijs and DellasCollard et al., 2019; JOGG-Aanpak, n.d.; Reference Renders, Halberstadt and FrenkelRenders et al., 2010). Early developments in JOGG’s network building included partnering with six business partners to focus on promoting good nutrition and exercise, but quickly developed into a national effort (Reference Slot-Heijs, Gutter and DellasSlot-Heijs et al., 2020). In 2018, JOGG signed the National Prevention Agreement, elevating its role in promoting a healthier Netherlands (Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport, 2019). With 90% of funding coming from the Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport, JOGG is now a national organization that recommends and helps municipalities implement strategies (Reference Slot-Heijs, Gutter and DellasSlot-Heijs et al., 2020).

Between 2015 and 2019, JOGG expanded in four important ways. First, the amount of funding that JOGG received from the Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport almost doubled between 2015 and 2019, from $3.9 million to $7.6 million. Second, the number of social partners grew from 16 in 2015 to 22 in 2019 and the number of business partners grew from 6 in 2015 to 14 in 2019. Third, the number of municipalities partnering with JOGG (JOGG municipalities) grew from 91 in 2015 to 143 in 2019. As a result, the number of children and youth living in JOGG municipalities grew from 545 243 in 2015 to 1 195 111 in 2019, a number that represents nearly half of the country’s youth population. Finally, the percentage of JOGG municipalities that have appointed a JOGG director for at least 16 hours per week grew from 41% in 2015 to 81% in 2019 (Reference Slot-Heijs, Gutter and DellasSlot-Heijs et al., 2020).

JOGG’s growth results from the Netherlands’ response to an alarming outlook that projected an increase in adult overweight and obesity. According to the Netherlands Public Health Future Outlook, the percentage of overweight Dutch adults will rise from 49% in 2015 to 62% in 2040 (National Institute for Public Health and the Environment, 2018). Rising overweight and obesity is especially alarming because of a resulting impact on social costs. For example, rising overweight and obesity contributed to 3.7% of the burden of disease and €1.5 billion in health care costs in the Netherlands in 2018 (Reference Gibson, Allen and DavisGibson et al., 2017; National Institute for Public Health and the Environment, 2018; Reference Quek, Tam and ZhangQuek et al., 2017). As a result, the 2018 Dutch National Prevention Agreement, which JOGG signed, highlighted overweight and obesity in order to reverse these trends (Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport, 2019). Furthermore, JOGG decided that the Netherlands’ youth population is an appropriate area to intervene because 13.2% of children aged 4 to 18 years in the Netherlands were overweight or obese in 2018 (National Institute for Public Health and the Environment, 2018).

The “JOGG approach” connects stakeholders and intervenes in living environments to promote health among people younger than 19 years old (JOGG-Aanpak, n.d.). Because the focus is to improve health by altering the physical and social environments around youth, the JOGG approach exemplifies the potential for co-benefit between SDG3 and SDG11. The JOGG approach addresses seven environments that children and youth contact the most: home, neighbourhood, school, sport, leisure, work and media (JOGG-Aanpak, n.d.). Several of these environments correspond closely to the physical and social environments described in the Urban Health System Governance Framework (Fig. 11.1). For example, home and neighbourhood, key intervention environments, are part of the built environment (SDG11). In the city of Eindhoven, JOGG partnered with Ballast Nedam Development, a private developer, to promote healthy urbanization on the Berckelbosch development project (Ballast Nedam Development, 2020). The Berckelbosch development project involves the development of 950 homes in Eindhoven and the partnership with JOGG involves creating a healthier urban environment with ample green space, safe walking and biking, and infrastructure for sports and games (Berckelbosch Reference EindhovenEindhoven, n.d.).

Preliminary results suggest that the JOGG approach improves health (SDG3) and promotes health equity (SDG10). While two studies conflict in their analysis of the overweight prevalence in children between JOGG and non-JOGG areas, both show an overall decrease in overweight prevalence of almost 10% in JOGG areas over the study period (Reference Kobes, Kretschmer and TimmermanKobes, Kretschmer & Timmerman, 2021; National Institute for Public Health and the Environment, 2020). However, this result must be interpreted with caution. The studies do not rule out the possibility that decreases in overweight and obesity were happening before JOGG was implemented, that other initiatives may be more responsible for the decrease, or that relevant differences between municipalities skew the results (National Institute for Public Health and the Environment, 2020). In fact, one study concluded that it is socioeconomic status (SES) that most likely explains this result, not the approach’s success. Yet when analysing only low SES areas that implemented JOGG at least six years ago, which were typically areas with the highest overweight prevalence, this study showed a significant decrease in overweight prevalence, suggesting that JOGG is especially successful in the areas most severely affected by overweight and obesity (Reference Kobes, Kretschmer and TimmermanKobes, Kretschmer & Timmerman, 2021). The preliminary results suggest that JOGG improves health in some areas (SDG3) and the unequal reach of the intervention is moving in a positive direction, where low SES areas are more strongly benefited, thereby promoting health equity across Dutch municipalities. According to the Health System Governance Framework (Fig. 11.1), this is a case where the intervention on the physical and social environments alleviates urban health inequities (SDG10).

The JOGG approach has significant potential for co-benefits with other SDGs, which increases its importance. SDGs 4 (Quality education) and 2 (Zero hunger) are two examples. Over 1500 schools work with Healthy School, an initiative funded in part by JOGG (JOGG-Aanpak, n.d.). Healthy School is a national collaboration between several ministries that have developed a step-by-step plan for promoting an educational environment that helps children thrive. It involves four pillars: education to develop skills needed for a healthy lifestyle; a school environment that helps children pursue a healthy lifestyle; identification of health problems at an early age; and incorporation of health promotion measures into school policy (Gezonde School, n.d.). JOGG also used the school environment to address food security (SDG2). Over the 2020–2021 school year, JOGG piloted a programme to improve healthy food in schools in the cities of Alkmaar, Lelystad and Katwijk. The pilot was focused on limiting an unhealthy food supply in the municipality, making the food supply around schools healthier, and influencing healthy choices within schools (JOGG, 2021).

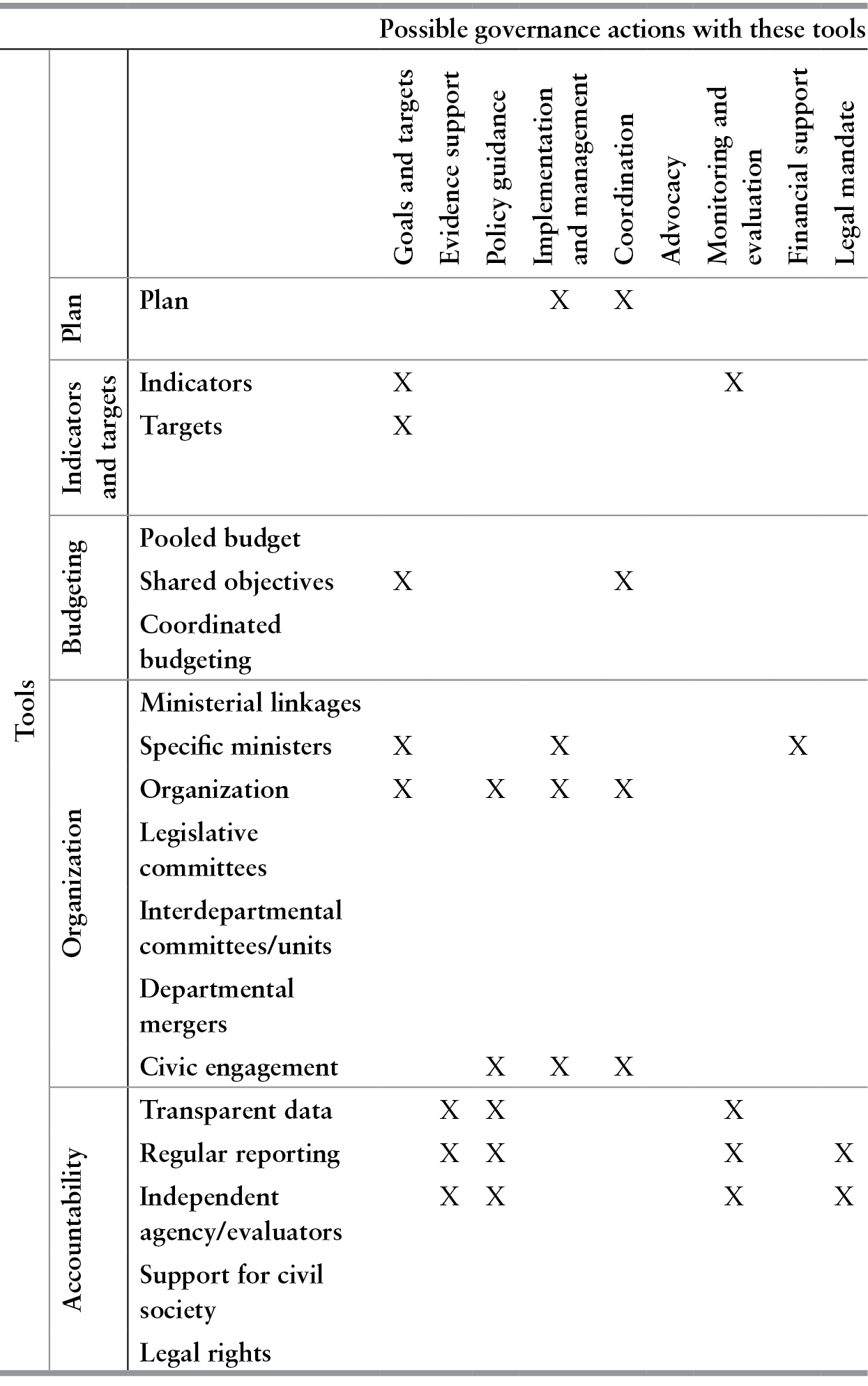

The Intersectoral Governance Framework (Table 11.1) describes the tools and actions JOGG used to produce co-benefits between SDG11 and SDG3. The table reflects organizational shifts from the Dutch National Prevention Agreement, intervention through civic engagement, and accountability through evaluation. First, along with the Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport and various social partners, JOGG helped to develop and signed the National Prevention Agreement in 2018, which committed JOGG and its partners to a coordinated plan, increased JOGG’s funding, set its goals and targets, identified shared objectives across partners and ministries, and altered its organizational structure. In 2019, 90% of JOGG’s $8.5 million budget was funded by the Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport (Reference Slot-Heijs, Gutter and DellasSlot-Heijs et al., 2020). The National Prevention Agreement created the target and indicator to reduce youth overweight and obesity prevalence to 9.1% and 2.3% respectively by 2040 (Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport, 2019). Many of JOGG’s business and social partners provided input and signed the agreement, and the agreement identifies shared objectives between ministries. For example, the National Prevention Agreement identifies cycling to school and work as an intervention area, which overlaps with the transportation goals of the Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management (Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport, 2019). Also in response to the National Prevention Agreement, JOGG’s organizational structure changed, obtaining a board of directors and a scientific advisory committee to manage and advise JOGG’s progress and evaluation methods. Second, JOGG intervenes through partnership with municipalities and helps them implement local interventions. JOGG municipalities utilize members from the municipality to form a JOGG team that includes a JOGG director, JOGG policy officer and other stakeholders from the municipality in order to promote civic engagement (JOGG-Aanpak, n.d.). As a reflection of local partnership, the Association of Dutch Municipalities, which represents the interests of all Dutch municipalities, also committed to the National Prevention Agreement (Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport, 2019). Third, JOGG is held accountable through evaluation. The National Prevention Agreement also mandated that the National Institute for Public Health and the Environment, an independent agency, will monitor progress towards the goals in order to guide policy decisions (Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport, 2019). This agency, in collaboration with the Mulier Institute, has produced annual reports for JOGG since 2015 (Reference Slot-Heijs, Gutter and DellasSlot-Heijs et al., 2020). JOGG also provides transparent data to document its partnerships and partner municipalities (JOGG-Aanpak, n.d.).

Table 11.1 Intersectoral governance framework: the case of JOGG

| Tools | Possible governance actions with these tools | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Goals and targets | Evidence support | Policy guidance | Implementation and management | Coordination | Advocacy | Monitoring and evaluation | Financial support | Legal mandate | ||

| Plan | Plan | X | X | |||||||

| Indicators and targets | Indicators | X | X | |||||||

| Targets | X | |||||||||

| Budgeting | Pooled budget | |||||||||

| Shared objectives | X | X | ||||||||

| Coordinated budgeting | ||||||||||

| Organization | Ministerial linkages | |||||||||

| Specific ministers | X | X | X | |||||||

| Organization | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Legislative committees | ||||||||||

| Interdepartmental committees/units | ||||||||||

| Departmental mergers | ||||||||||

| Civic engagement | X | X | X | |||||||

| Accountability | Transparent data | X | X | X | ||||||

| Regular reporting | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Independent agency/evaluators | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Support for civil society | ||||||||||

| Legal rights | ||||||||||

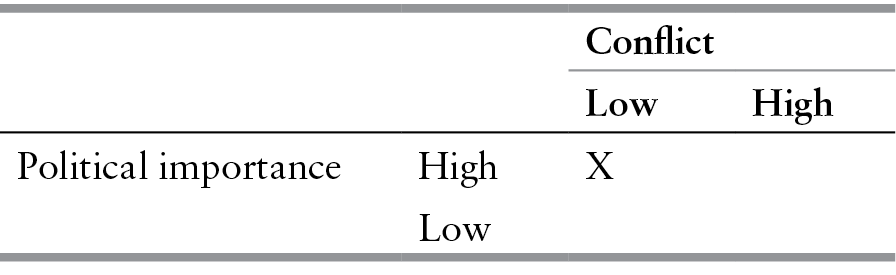

The JOGG approach is favourable on the conflict-political importance scale represented in Table 11.2. The JOGG approach has become more important and less conflictual in the last several years, as indicated by its rapid growth. Continued expansion will indicate the increasing popularity of this intervention. While the intervention is popular, a legal mandate as well as a more active role in coordinating and recommending municipal actions from the national government may improve the intervention’s reach. For example, a legal mandate could require all municipalities to meet a set of recommendations in the seven environments that JOGG prioritizes. Further, JOGG must be careful to minimize conflicts of interest among its business and social partners. The EPODE International Network, of which JOGG is a member, is funded by Nestlé, potentially causing conflicts of interest to arise from food retailers that have an adverse impact on obesity rates (Reference Borys, Le Bodo and JebbBorys et al., 2012; Cision, 2012). Nevertheless, JOGG is a strong example of an intervention with low political conflict and high political importance that has benefited youth health by emphasizing healthy change to surrounding environments and prioritizing building a strong network of partners.

Table 11.2 Political importance and conflict: the case of JOGG

| Conflict | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | ||

| Political importance | High | X | |

| Low | |||

11.5 Case study 2: Superblocks in Barcelona

Over the last couple of decades, Barcelona has experienced challenges attributed to population growth that have impacted the health and health behaviours of its residents (Agència Reference de Salut Públicade Salut Pública, 2021). This has included a rise in environmental hazards including air pollution, while traffic injuries and a lack of green spaces have contributed to rising sedentary behaviours and health complications. At pre-2020 pollution levels (years 2018–2019), it was estimated that in the city of Barcelona 7% of natural deaths (about 1000 deaths per year), about 11% of new cases of lung cancer (about 110 cases per year) and about 33% of new cases of childhood asthma (about 525 cases per year) were attributed to air pollution in excess of WHO recommendations (10 µg/m³ PM2.5 and 20 µg/m³ NO2) (Reference Rico, Font and ArimonRico et al., 2020). In response to these issues and others, in May 2016, the Barcelona city council approved the measure “Omplim de vida els careers” (“Improving life on the streets”), to create Superblocks across the city (Ajuntament de Barcelona, n.d.; Reference Mehdipanah, Novoa and León-GómezMehdipanah et al., 2019; Reference RuedaRueda, 2016). The Barcelona Superblocks consist of amalgamations of blocks throughout the city to improve the habitability of public spaces, sustainable mobility, and urban green, and to promote residents’ participation and co-responsibility (Ajuntament de Barcelona, n.d.). If the initially planned 503 Superblocks were to be implemented, it is estimated that it would reduce annual air pollution by 24% and could prevent almost 700 annual premature deaths (Reference Mueller, Rojas-Rueda and KhreisMueller et al., 2020). Ultimately, the Barcelona Superblock programme aims to achieve the sustainable city and community development goal of SDG11 by improving the physical and social environments within intervened areas (Fig. 11.1).

The Barcelona Superblocks were developed by the Department of Ecology and Infrastructures of the Barcelona city council. Each superblock promotes universal accessibility by redeveloping interior spaces for pedestrians and cyclists while creating more opportunities for public spaces to help facilitate cultural, economic and social exchanges. By reducing speed limits to 10km/h and increasing public spaces, the Superblocks aim to ultimately improve quality of life for residents and create more opportunities for social cohesion and economic activity. At the heart of this intersectoral approach to the Barcelona Superblocks is the participatory process that is meant to be inclusive of residents living within the intervention neighbourhoods. A three-step planning process is undertaken. First, a team from the city’s Department of Planning and Prospection and the Management of Urban Model Projects drafts an Action Plan for each designated area. Second, through a participatory process involving neighbourhood associations and residents, each Action Plan is finalized. Third, the Action Plan is implemented. Through a partnership with the Public Health Agency of Barcelona, the Superblocks were evaluated for their effects on the environment, health and health inequities (Agència de Salut Publica, n.d.). Currently, although they are small interventions, five superblocks have been completed, with another three within the implementation process. The goal is to implement Superblocks in each of Barcelona’s ten districts.

So far, the initiative has reduced air and noise pollution, promoted more interactions among residents, and some improvements in physical activity (Agència de Salut Publica, n.d.). Although there are still concerns among residents around traffic congestion and safety, the Barcelona Superblocks are an important example of urban governance addressing issues associated with urban growth.

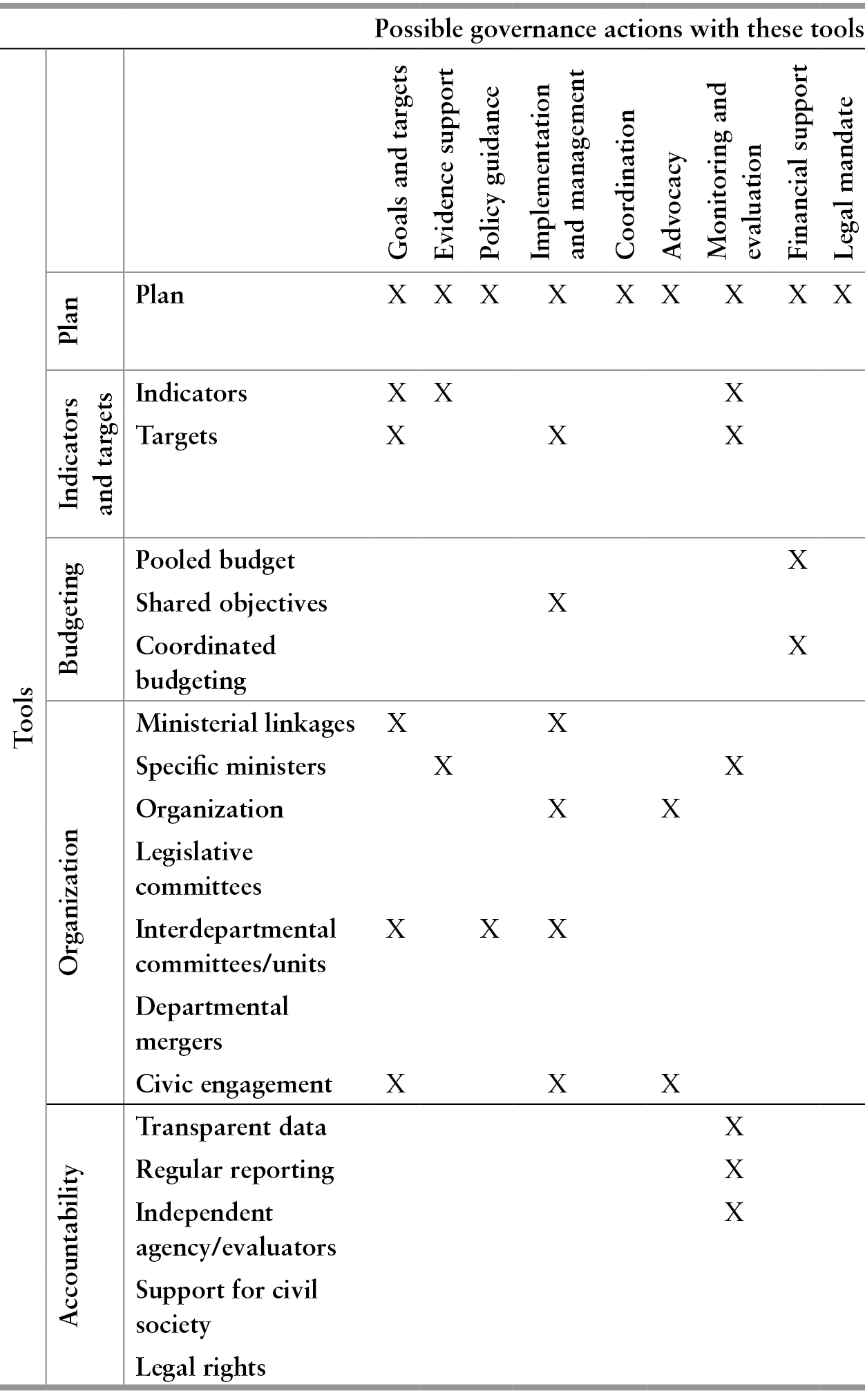

Using the Intersectoral Governance Framework (Table 11.3), planning was used as a tool across all possible governance actions including setting goals and targets, guiding policy and the implementation and management of the programme. Multiple departments are involved throughout the planning, implementation and evaluation phases, including the role of the Barcelona Public Health Agency in assessing the environmental and health impacts of the Superblocks (Reference Mehdipanah, Novoa and León-GómezMehdipanah et al., 2019; Reference Palència, León-Gómez and BartollPalència et al., 2020). Central to the Barcelona Superblocks is the public engagement piece that ensures residents provide input on the planning and implementation phases of the projects. Furthermore, residents’ opinions are captured through surveys and interviews post-implementation to better understand the perceptions towards multiple aspects of the projects including traffic, public spaces and social networking opportunities. In addition, businesses are also interviewed to better understand the economic gains of these projects through the greater foot traffic and visibility provided.

Table 11.3 Intersectoral governance framework: the case of the Barcelona Superblocks

| Tools | Possible governance actions with these tools | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Goals and targets | Evidence support | Policy guidance | Implementation and management | Coordination | Advocacy | Monitoring and evaluation | Financial support | Legal mandate | ||

| Plan | Plan | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Indicators and targets | Indicators | X | X | X | ||||||

| Targets | X | X | X | |||||||

| Budgeting | Pooled budget | X | ||||||||

| Shared objectives | X | |||||||||

| Coordinated budgeting | X | |||||||||

| Organization | Ministerial linkages | X | X | |||||||

| Specific ministers | X | X | ||||||||

| Organization | X | X | ||||||||

| Legislative committees | ||||||||||

| Interdepartmental committees/units | X | X | X | |||||||

| Departmental mergers | ||||||||||

| Civic engagement | X | X | X | |||||||

| Accountability | Transparent data | X | ||||||||

| Regular reporting | X | |||||||||

| Independent agency/evaluators | X | |||||||||

| Support for civil society | ||||||||||

| Legal rights | ||||||||||

The Barcelona Superblocks involve multiple players in the funding, development, implementation and evaluation processes. For example, funding came together from pooling and coordinating budgets from the federal and regional governments through initiatives aimed to support public transportation. This illustrates that through the programme’s multiple outcomes, including the reduction of environmental hazards and better transportation, the Barcelona Superblocks are well positioned to attract and attain diverse financial support.

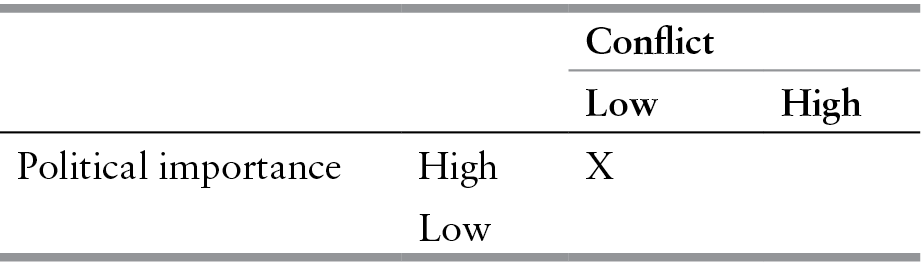

On a political importance and conflict scale, the Barcelona Superblock is of high political importance and high conflict (Table 11.4). The Superblock initiative addresses major issues the city faced in relation to air pollution and traffic. Concerns have been raised through residents and community organizations in relation to potential gentrification and displacement, in addition to the unequal distribution of health benefits, particularly in the initial neighbourhoods where residents’ input was not considered. Residents have demonstrated both support and opposition (Reference TorresTorres, 2019). At a political level, the initiative has been challenged by the conservative opposition and used to criticize the progressive government of Ada Colau, the current mayor of Barcelona (Reference KlauseKlause, 2018).

Table 11.4 Political importance and conflict: the case of the Barcelona Superblocks

| Conflict | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | ||

| Political importance | High | X | |

| Low | |||

Nonetheless, sustainability and continued financial investment in such a programme is an imminent concern, particularly when regional or state level governments dictate programme funding. This has been an issue in Barcelona where, in 2011, the Llei de Barris (Neighbourhood Law) urban renewal programme had invested approximately €1.3 billion in improving 143 largely disinvested neighbourhoods throughout the Catalonia region (Departament de Politica Territorial i Obres Publiques, 2009). While the goal was to continue expanding the programme, in 2012, the newly elected conservative coalition suspended the programme’s funding. Although the government made a renewed commitment to complete existing programmes in 2014, disruptions through unfinished programmes had impacted neighbourhood residents and businesses (Reference Mehdipanah, Rodríguez-Sanz and MalmusiMehdipanah et al., 2014).

To prevent similar occurrences, programmes like the Barcelona Superblocks must seek multiple funding sources, including both public and private investments to ensure the continuity of growth. They must also continue working with various sectors to demonstrate the added value the initiative brings, including public health, where a recent evaluation showed the positive effects on health with an improvement in the quality of life of residents and people who used the Superblocks. The reduction in noise, improvement in sleep quality, decrease in air pollution and increase in social interactions were all contributing factors to the improved wellbeing reported by residents (Agència de Salut Publica, n.d.).

11.6 Conclusion

In this chapter we presented a background for understanding the close relationship between urban planning and public health, a framework for understanding the co-benefits between SDG11 and SDG3, and two examples that illustrate health system governance in urban areas. Through this work, two important themes necessary to understand co-benefits between the two SDGs emerged. First, achieving SDG11, that is, making cities healthy, sustainable, inclusive and resilient, is a prerequisite to achieving good health and wellbeing (SDG3). Under the health system governance framework identified in the causal pathways section, we showed that health systems govern through altering the physical and social environment with direct and indirect health impacts. With a growing population living in cities, the importance of SDG11 as a catalyst to achieve good population health and wellbeing cannot be underestimated. As we identified above, green spaces in a city allow for exercise, quality transportation is necessary to acquire resources such as medical care, and vaccine equity is necessary for achieving strong population health. In addition, the JOGG and superblocks interventions suggest that a healthy, sustainable, inclusive and resilient city has potential to improve population health. The JOGG approach targets the environment surrounding a child to promote healthy growth and the superblocks create public spaces that allow for residents to connect. To create co-benefits between SDG3 and SDG11, intervening on SDG11, the built environment around the population, with the goal of improving health is a common and strong approach.

Second, addressing health inequities should be a strong priority in ensuring urban growth is sustainable, inclusive and resilient, and to promote equity, the health system and other urban governance structures must work together to create strong intersectoral collaboration. More equitable policies and practices around land development and zoning can produce more equitable growth, reduce negative impacts of for-profit development, including gentrification, and promote good health and wellbeing (Reference Basu, Andrews and KishoreBasu et al., 2012; Reference Dahrouge, Hogg and MuggahDahrouge et al., 2018; Reference Martínez, Smith and Llop-GironésMartínez et al., 2016; Reference Sumah, Baatiema and AbimbolaSumah et al., 2016). Stronger coordination between public and private, health care and social services, and profit-making and mission-driven sectors in a health system can promote the commitment to equity necessary for sustainable, inclusive and resilient cities. The JOGG and superblocks interventions are excellent examples of interventions that are developing strong intersectoral partnerships. Through partnership with the Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport, municipalities, business partners and social partners, JOGG has reduced overweight prevalence in low-SES areas, improving health equity in the Netherlands. Using interdepartmental collaboration and public engagement, the superblocks intervention has reduced air and noise pollution, promoted more interactions among residents, and improved physical activity.

As countries look to improve their commitment to building sustainable, healthy, inclusive and resilient cities, stronger coordination across multiple sectors is needed to ensure policies and programmes targeting equitable growth are in place to prevent the negative consequences of rapid urbanization. As the global population continues to shift towards urban living, these areas must provide opportunities for residents to thrive healthfully.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Dr Katherine Pérez and the Salut als Carrers Working Group for their guidance on the Barcelona superblocks case study.