Article contents

Social Determinism and Rationality as Bases of Party Identification*

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 01 August 2014

Extract

In The Responsible Electorate, V. O. Key urged upon us “the perverse and unorthodox argument … that voters are not fools.” He challenged the notion that the voting act is the deterministic resultant of psychological and sociological vectors. He believed that the evidence supported the view of the voter as a reasonably rational fellow. The present article offers a corollary to Key's “unorthodox argument.” It suggests that certain sociological determinants, secifically group norms regarding party identification, may, upon examination, prove to be rational guides to action. For the voter who is a reasonably rational fellow, it will be argued, these group norms may seem rather sensible.

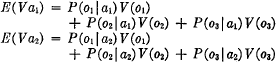

Before proceeding to the analysis of data, some discussion of the notion of rationality seems in order. The usage subscribed to in the present analysis derives from contemporary game theory. Put most simply, being rational in a decision situation consists in examining the alternatives with which one is confronted, estimating and evaluating the likely consequences of each, and selecting that alternative which yields the most attractive set of expectations. Formally, this process entails making calculations of the following type as a basis for the decision:

where:

E(Vai) = expected value of alternative i.

P(oj∣ai) = probability of outcome j given that V(oi) = value of outcome j to the decision maker.

- Type

- Research Article

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Political Science Association 1969

Footnotes

Much of the development and analysis in this article is a byproduct of efforts to develop a dynamic model of voting behavior. These efforts were funded by the National Science Foundation during the summers of 1966 and 1967. The body of data used in the present analysis was provided by the Survey Research Center at the University of Michigan. It is comprised of the 1956 election study (#417) plus occasional items from the 1958 and 1960 waves of the same panel.

References

1 Key, V. O. Jr. The Responsible Electorate (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1966), p. 7 CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

2 See Luce, R. Duncan and Raiffa, Howard, Games and Decisions (New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc., 1957), Chapter IIGoogle Scholar.

3 One may regard education, from this point of view, as a capital investment oriented toward long-run reduction of information and calculation costs. For these notions on rationality and education, I am indebted to Peter C. Ordeshook, from whose work on a general rationality model of electoral behavior they are derived.

4 The seminal work here has been Downs, Anthony, An Economic Theory of Democracy (New York: Harper and Row, 1957)Google Scholar. For critical appraisals see: Stokes, Donald E., “Spatial Models of Party Competition,” this Review, 57 (1963), 368–377 Google Scholar; and Converse, Philip E., “The Problem of Party-Distances in Models of Voting Change,” in Jennings, M. Kent and Zeigler, L. Harmon (eds.), The Electoral Process (Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1966), Chapter IXGoogle Scholar.

5 See, for example: Buchanan, James M. and Tullock, Gordon M., The Calculus of Consent (Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 1962)Google Scholar; Davis, Otto A. and Hinich, Melvin, “A Mathematical Model of Policy Formation in a Democratic Society,” Mathematical Applications in Political Science, II. Arnold Foundation Monographs XVI. (Dallas, Texas: Arnold Foundation, Southern Methodist University, 1966), 175–208 Google Scholar; and Riker, William H. and Ordeshook, Peter C., “A Theory of the Calculus of Voting,” this Review, 62 (03, 1968), 25–42 Google Scholar.

6 Downs, op. cit.

7 For example, in Burdick, Eugene and Brodbeck, Arthur J. (eds.), American Voting Behavior (Glencoe, Illinois: The Free Press, 1959)CrossRefGoogle Scholar, see Arthur J. Brodbeck, “The Problem of Irrationality and Neuroticism Underlying Political Choice,” Franz Alexander, “Emotional Factors in Voting Behavior,” and Richard E. Renneker, “Some Psychodynamic Aspects of Voting Behavior.”

8 See Edelman, Murray, The Symbolic Uses of Politics (Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 1964)Google Scholar.

9 See, for example: Berelson, Bernard R., Lazarsfeld, Paul F., and McPhee, William N., Voting (The University of Chicago Press, 1954), Chapters IX–XGoogle Scholar; Campbell, Angus, Converse, Philip E., Miller, Warren E., and Stokes, Donald E., “Party Loyalty and the Likelihood of Deviating Elections,” Journal of Politics, 24 (1962), 689–702 Google Scholar.

10 See: Hyman, Herbert H., Political Socialization (Glencoe, Illinois: The Free Press, 1959), Chapters II–IIIGoogle Scholar; Easton, David and Hess, Robert D., “The Child's Political World,” Midwest Journal of Politics, 6 (1962), 229–246 CrossRefGoogle Scholar; and Greenstein, Fred I., Children and Politics (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1965), Chapter IVGoogle Scholar. An overview of the socialization processes involved is provided in Lane, Robert E. and Sears, David O., Public Opinion (Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1964)Google Scholar.

11 Cf. Campbell, et. al., op. cit. p. 147; see also Converse, Philip E. and Dupeux, Georges “Politicization of the Electorate in France and the United States,” Public Opinion Quarterly, 26 (1962), p. 14 CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

12 The reader should note, at this point, that in the operation to be described, statistical averages of a national sample were used as representations of felt environmental norms. This dubious procedure will be discussed at a later point in the analysis (see pp. 10, below). Particular sociological characteristics were chosen with a view toward reducing the discrepancies between such averages and felt norms and with a concern for minimizing multicollinearities. The specific characteristics utilized were: religion, self-rating on class, size of community, region (South, non-South), and race (white, non-white).

13 In all cases, nominal data were converted to dummy variables and treated as prescribed in Suits, Daniel B., “The Use of Dummy Variables in Regression Equations,” Journal of the American Statistical Association, 52 (1957), 548–551 CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

14 The reader's attention is called to the fact that paternal partisan preference is ascertained on the basis of respondent's recall. Work by M. Kent Jennings and Richard G. Niemi suggests something of the magnitude of the error thus induced. From the point of view of correlation, Niemi finds a Kendall's tau of 0.60 between party identification claimed by the respondent's father and that ascribed to the father by the respondent. See Niemi, Richard G., A Methodological Study of Political Socialization in the Family (unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Michigan, 1967), pp. 113–115, and 128 Google Scholar. A further analysis of this data by this writer with the cooperation of Professor Niemi indicates that 78.4% of the students correctly identify their fathers in the broad categories of Democrat, Independent, Republican. The 21.6% of incorrect identifications are about evenly split between incorrect assignment with regard to the category of Independent (10.6%) and assignment to incorrect partisanship (11.0%).

Insofar as there is any systematic bias in the errors, it seems to operate in a manner not seriously debilitating to the present analysis. Respondents appear to be biased toward perceiving their parents as having a partisanship which is “normal” for people of like social characteristics. Thus where parents are identified as having a sociologically deviant identification, the ascribed identification is apt to be correct. This is rather important as such identification proves of central concern in the present analysis. See Niemi, op. cit., pp. 126–128.

15 See Blalock, Hubert M. Jr., Social Statistics (New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc., 1960), pp. 232–234 Google Scholar.

16 About the best that has been done along these lines with a single variable is the 7.29% of the variance in level of voter stability explained by family reinforcement, in McClosky, Herbert and Dahlgren, Harold E., “Primary Group Influence on Party Loyalty,” this Review, 53 (1959), 774 Google Scholar.

17 Clearly some qualms arise in using the residuals of a linear regression analysis in which the dependent variable was dichotomous. One worries about saturation effects, etc. [See Goldberg, Arthur S., Econometric Theory (New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc., 1964), pp. 248–251 Google Scholar.] In the actual event, visible saturation effects were infrequent (less than 1% of the cases had predicted values less than zero or greater than one). Moreover, the dichotomous nature of the dependent variable offered certain advantages. First, there is only one possible way to obtain each non-zero value of the residual. Second, there are only two points at which the residuals can be zero, namely, where the predicted and actual values are zero, and where the predicted and actual values are one. These polar points become, in effect, the “normal” points for their respective segments of the distribution (this division occurring at that value of X which yields a predicted value of y of 0.5). Thus, by comparing any two cases on the basis of the absolute values of their residuals, one can say which is closer to his respective “normal” point. It is on this basis that sociological deviance in paternal party identification was measured.

18 See Dahl, Robert A., Who Governs? (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1961), Chapter V, especially Table 5.4, p. 60 Google Scholar.

19 Campbell, et. al., op. cit., pp. 458–459.

20 Henry W. Riecken, “Primary Groups and Politcal Party Choice,” in Burdick and Brodbeck, op. cit., p. 167.

21 Ibid., pp. 167–168. The relevant works are: Berelson, Lazarsfeld, and McPhee, op. cit.; Maccoby, Eleanor E., Matthews, Richard E., and Morton, Anton S., “Youth and Political Change,” Public Opinion Quarterly, 18 (195?), 23–29 CrossRefGoogle Scholar; McClosky and Dahlgren, op. cit. An intimation of the findings of the present study may be seen in Converse, Philip E.. “The Nature of Belief Systems in Mass Publics,” in Apter, David E. (ed.), Ideology and Discontent (London: Collier-Macmillan Limited, The Free Press of Glencoe, 1964), pp. 231–233 Google Scholar.

22 At this point, it may be worth noting that this concept (sociological deviance) helps to clarify at least one peculiar finding in the existing literature. In The American Voter, Campbell, et al., after noting that the direction of intergenerational social mobility, as measured by occupational status differences, did not seem to be associated with shifts toward the Republican or Democratic identification go on to note, on pp. 458–459, n. 15, that:

Upward mobile people are slightly more likely to have shifted from Democrat to Republican identification, than those people whose status has moved downward, but both types of changers are more likely to have moved toward the Republican Party than away from it. [My italics.]

However, this appears to be a consequence of the operation of sociological deviance in paternal party identification, because when analysis is confined to those respondents whose fathers were normally identified, the findings are more in line with what one might traditionally have expected. Upward mobile offspring of Democrats are more apt to become Republicans than are downward mobile off-spring of Democrats. Conversely, downward mobile offspring of Republicans are more apt to become Democrats than are upward mobile offspring of Republicans. Moreover, contrary to the SRC suggestion, the downward mobile progency of normal Republicans are more likely to become Democrats than are such progency of normal Democrats to become Republicans. Finally, where occupational status has not changed between generations, the Republicans have lost more than the Democrats—a finding compatible with the history of the Republican party over the past thirty years.

23 Strictly speaking, the reduction is calculated against a null model which is based upon random assignment in proportions prescribed by the distribution on the dependent variable. For clarification, the reader is again referred to Blalock, loc. cit.

24 Lest the reader be apprehensive that the findings in Table VI reflect only the impact of education on offspring of sociologically deviant Democratic identifiers, through the ensuring that such offspring will be in a Republican environment, a further breakdown is presented below.

25 See n.3, above.

26 Maccoby, Matthews, and Morton, op. cit.

27 The problem raised by such an index is that it is difficult, probably impossible, to ascertain which permutation of the components is reflected in a particular instance of a given value of the index, yet it is by no means clear that a given value of the index has the same theoretical relationship to the independent variables, regardless of the permutation of components upon which it is based.

28 Maccoby, Matthews, and Morton, op. cit., p. 38.

29 See n. 10, above.

30 For operational procedures see: Goldberg, Arthur S., “Discerning a Causal Pattern Among Data on Voting Behavior,” this Review, 60 (12, 1966), 922 Google Scholar.

31 Cf. Blalock, loc. cit.

32 Cf. McPhee, William N., Formal Theories of Mass Behavior (London: Collier-Macmillan Ltd., The Free Press of Glencoe, 1963), Chapter IIGoogle Scholar. See also McPhee, William N. and Glaser, William A., Public Opinion and Congressional Elections (New York: The Free Press of Glencoe, 1962), esp. pp. 139–151 Google Scholar.

33 Pool, Ithiel de Sola, Abelson, Robert P., and Popkin, Samuel L., Candidates, Issues, and Strategies (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The M.I.T. Press, 1964)Google Scholar.

34 Ibid., pp. 54–56.

35 Ibid., pp. 56–57.

36 Ibid., pp. 102–106.

37 Despite Key's laudable efforts in this direction in The Responsible Electorate (see for example, pp. 79–89 of that work), I suggest that the question remains open.

38 Berelson, Lazarsfeld, and McPhee, op. cit., p. 91.

39 Maccoby, Matthews, and Morton, op. cit.

40 Ibid., pp. 33–36.

41 McClosky and Dahlgren, op. cit.

42 Jackson, Elton F. and Crockett, Harry J. Jr., “Occupational Mobility in the United States: A Point Estimate and Trend Comparison,” American, Sociological Review, 29 (1964), 5–15 CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

A correction has been issued for this article:

- 9

- Cited by

Linked content

Please note a has been issued for this article.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.