Introduction

The Cambrian Explosion marks the most important biodiversification event in Earth history (Erwin and Valentine, Reference Erwin and Valentine2013). All major animal body plans appeared in the fossil record during this biodiversification event, setting the stage for the evolution of modern animal phyla (Knoll and Carroll, Reference Knoll and Carroll1999; Erwin et al., Reference Erwin, Laflamme, Tweedt, Sperling, Pisani and Peterson2011). Recently, our understanding of the Cambrian Explosion has been significantly improved, in large part due to systematic studies of various exceptionally preserved fossil assemblages or Konservat-Lagerstätten from the early−middle Cambrian Period, including the Sirius Passet, Chengjiang, Guanshan, Emu Bay Shale, Kaili, and Burgess Shale biotas (Holmes et al., Reference Holmes, García-Bellido and Lee2018). One of the early Cambrian Lagerstätten that has yet to be brought under the spotlight is the Hetang biota, which occurs in deepwater black shales of the lower-middle Hetang Formation in southern Anhui Province of South China (Fig. 1). The Hetang biota is dominated by sponge fossils and contains some of the earliest articulated sponges, particularly abundant in a unit of highly organic-rich and combustible mudstone (known locally as the stone coal unit) in the lower Hetang Formation (Hu et al., Reference Hu, Chen, Yao-songWang, Jin-quanWang and Xun-lai2002; Yuan et al., Reference Yuan, Xiao, Parsley, Zhou, Chen and Hu2002; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Hu, Zhou, Xiao and Yuan2004; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Yang, Janussen, Steiner and Zhu2005; Xiao et al., Reference Xiao, Hu, Yuan, Parsley and Cao2005; Botting et al., Reference Botting, Muir, Xiao, Li and Lin2012; Botting et al., Reference Botting, Yuan and Lin2014). However, other macrofossils in the Hetang Formation are either poorly illustrated or largely ignored in previous studies (Yuan et al., Reference Yuan, Xiao, Parsley, Zhou, Chen and Hu2002; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Hu, Zhou, Xiao and Yuan2004). To more fully document the diversity of the Hetang biota, we describe a new group of problematic animal fossils from black shale/mudstone of the middle Hetang Formation (Cambrian Stage 2−3) in the Lantian area of South China. The fossils, described as a new taxon, Cambrowania ovata Tang and Xiao, new genus new species, may represent either the carapace of bivalved arthropods or early life stages of sponges.

Figure 1. Geological map and stratigraphic column of the Neoproterozoic–lower Cambrian succession in the Lantian area of southern Anhui Province in South China. lo. = lower; LGW = Leigongwu Formation; Fm. = formation; SSF = small shelly fossils.

Geological setting

The Hetang Formation is mainly distributed in southern Anhui and neighboring northern Jiangxi and western Zhejiang provinces. It can be traced with relative ease in these areas, although its stratigraphic thickness may vary in places (Xue and Yu, Reference Xue and Yu1979). In this study, we focus on the Lantian area of southern Anhui Province where the Hetang Formation overlies siliceous rock of the largely terminal Ediacaran Piyuancun Formation and underlies the early Cambrian limestone of the Dachenling Formation (Fig. 1). Regionally, the Hetang Formation is ~318 m in maximum thickness. It can be subdivided into four lithostratigraphic units. The basal unit is a ~68 m thick siliceous-carbonaceous mudstone rich in phosphorite nodules at the base. Overlying this basal unit are, in ascending stratigraphic order, the lower unit of ~30 m thick stone coal (combustible organic-rich mudstone), the middle unit of ~110 m thick siliceous-carbonaceous mudstone and shale, and the upper unit of ~110 m thick carbonaceous shale with carbonate nodules. It should be noted that there are variations in the literature with regard to the lithostratigraphic boundary between the Piyuancun and Hetang formations: (1) some authors place the boundary just above the phosphorite nodule bed of the basal unit (Yue and He, Reference Yue and He1989; He and Yu, Reference He and Yu1992; Yue and Zhao, Reference Yue and Zhao1993; Xiao et al., Reference Xiao, Hu, Yuan, Parsley and Cao2005); (2) Xiang et al. (Reference Xiang, Schoepfer, Shen, Cao and Zhang2017) place the boundary at about 150 m below the stone coal unit; and (3) in regional geological survey reports (Bureau of Geology and Mineral Resources of Anhui Province, 1987) and in more recent literature (Steiner et al., Reference Steiner, Li, Qian, Zhu and Erdtmann2007; Dong et al., Reference Dong, Song, Xiao, Yuan, Chen and Zhou2012), the Piyuancun-Hetang boundary is placed at the base of the phosphorite nodule bed. In this paper we follow the latter stratigraphic treatment, in which the Ediacaran-Cambrian boundary is at or near the Piyuancun-Hetang boundary (contra Xiang et al., Reference Xiang, Schoepfer, Shen, Cao and Zhang2017) because the Piyuancun Formation contains typical terminal Ediacaran fossils whereas the phosphorite nodule bed contains basal Cambrian small shelly fossils (Dong et al., Reference Dong, Song, Xiao, Yuan, Chen and Zhou2012). Sedimentological and geochemical data suggest that the Hetang Formation was mainly deposited in a ferruginous slope-basinal environment (Zhou and Jiang, Reference Zhou and Jiang2009; Yuan et al., Reference Yuan, Cai, Wang, Xiang, Jia and Chen2014; Xiang et al., Reference Xiang, Schoepfer, Shen, Cao and Zhang2017).

The Hetang Formation contains abundant fossils that are biostratigraphically informative. Regionally, phosphorite in the basal unit contains small shelly fossils such as Anabarites trisulcatus Missarzhevsky in Voronova and Missarzhevsky, Reference Voronova and Missarzhevsky1969, Protohertzina anabarica Missarzhevsky, Reference Missarzhevsky1973, and Kaiyangites novilis Qian and Yin, Reference Qian and Yin1984 (Yue and He, Reference Yue and He1989; He and Yu, Reference He and Yu1992; Yue and Zhao, Reference Yue and Zhao1993; Steiner et al., Reference Steiner, Li, Qian, Zhu and Erdtmann2003), but no Cloudina or Sinotubulites. Although rare specimens of Anabarites and Protohertzina have been reported from the terminal Ediacaran Period (Zhu et al., Reference Zhu, Zhuravlev, Wood, Zhao and Sukhov2017; Cai et al., Reference Cai, Xiao, Li and Hua2019), the absence of Cloudina or Sinotubulites and the presence of Kaiyangites novilis indicate that the small shelly fossils from the Hetang Formation are characteristic of the basal Cambrian Anabarites trisulcatus–Protohertzina anabarica Assemblage Zone (Yao et al., Reference Yao, Xiao, Yin, Li and Yuan2005; Steiner et al., Reference Steiner, Li, Qian, Zhu and Erdtmann2007). In other words, the basal unit is likely Cambrian Fortunian in age. The stone coal in the lower unit contains abundant articulated sponge fossils (Xiao et al., Reference Xiao, Hu, Yuan, Parsley and Cao2005). Regional litho- and biostratigraphic correlation of the Hetang Formation in southern Anhui and western Zhejiang provinces indicates the lower unit or the stone coal unit may be Cambrian Stage 2 (Xiao et al., Reference Xiao, Hu, Yuan, Parsley and Cao2005). Carbonate nodules in the upper unit in western Zhejiang Province yield trilobites such as Hunanocephalus, Hupeidiscus, and Hsuaspis (Li et al., Reference Li, He and Ye1990; He and Yu, Reference He and Yu1992), which are indicative of Cambrian Stage 3 (Peng et al., Reference Peng, Babcock, Cooper, Gradstein, Ogg, Schmitz and Ogg2012). Therefore, the age of the carbonaceous mudstone and shale of the middle unit, from which the fossils reported in this paper were collected, is probably somewhere between Cambrian Stage 2 and Stage 3, with the ambiguity related to the uncertainty of the first appearance datum of trilobites in the Hetang Formation.

Materials and methods

In total, 436 specimens of Cambrowania ovata Tang and Xiao, n. gen. n. sp. were recovered from mudstone/shales of the middle Hetang Formation (Fig. 1). The majority of the specimens are preserved as carbonaceous compressions, although some are secondarily mineralized. All specimens were initially examined with reflected light microscopy (RLM) using an Olympus SZX7 stereomicroscope connected with an Infinity 1 camera. Well-preserved specimens were subsequently examined using backscattered electron scanning electron microscopy (BSE-SEM), secondary electron scanning electron microscopy (SE-SEM), and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) on an FEI Quanta 600FEG environmental SEM coupled with a Bruker EDX with a silicon-drifted detector (Muscente and Xiao, Reference Muscente and Xiao2015). The operating voltage in BSE-SEM, SE-SEM, and EDS modes was 5−20 kV in high-vacuum condition. Selected specimens with mineralized structures were scanned using an Xradia micro-CT to visualize internal structures. The X-ray source for the micro-CT scanning was operated at 90 kV and 88 μA with a flat area detector. The detector has a resolution of 2,048 × 2,048 pixels; each pixel size is 0.05 mm × 0.05 mm. The scanned sample was placed in the middle between the X-ray source and the detector. The source-object and source-detector distances were 25 mm and 155 mm, respectively. Under such geometric setting, the generated micro-CT images have a matrix size of 2,048 × 2,048 with the voxel size 4.40 μm × 4.40 μm.

Repository and institutional abbreviation

Types, figured, and other specimens examined in this study are reposited at Virginia Polytechnic Institute Geosciences Museum (VPIGM), Blacksburg, Virginia, USA.

Systematic paleontology

Phylum, Class, Order, Family incertae sedis

Genus Cambrowania Tang and Xiao, new genus

Type species

Cambrowania ovata Tang and Xiao, n. gen. n. sp.; by present designation; by monotypy.

Diagnosis

Spheroidal, ovoidal, or fusoidal truss-like fossils consisting of organic-rich, rafter-like crossbars or blades. The crossbars are nearly straight or slightly curved, singularly or doubly arranged, originally cylindrical and perhaps internally hollow, and interlaced to form a network-like truss. A terminal aperture may be developed.

Occurrence

Specimens were recovered from shale and mudstone of the middle Hetang Formation (Stage 2–3, lower Cambrian) in the Lantian area, South China.

Etymology

The genus name is derived from Cambrian and Wan (Anhui Province), referring to the stratigraphic and geographic occurrence of the type species.

Remarks

Cambrowania Tang and Xiao, n. gen. is distinguished from other known fossils of the early Cambrian Period, such as radiolarians (Braun et al., Reference Braun, Chen, Waloszek, Maas, Vickers-Rich and Komarower2007), the scyphozoan Olivooides (Dong et al., Reference Dong, Cunningham, Bengtson, Thomas, Liu, Stampanoni and Donoghue2013), and any known bivalved arthropods (Steiner et al., Reference Steiner, Li, Qian, Zhu and Erdtmann2003), by its spheroidal truss-like body plan with rafter-like crossbars that are cylindrical and internally hollow.

Cambrowania ovata Tang and Xiao, new species

Figures 2−6

Holotype

HT-T8-9V-25, illustrated in Figure 2.1, reposited at Virginia Polytechnic Institute Geosciences Museum (catalog number VPIGM-4729).

Figure 2. Cambrowania ovata Tang and Xiao, n. gen. n. sp. from the middle Hetang Formation. (1) Holotype, HT-T8-9V-25, VPIGM-4729. (2) Schematic sketch of specimen in (1), highlighting the marginal crossbars, interior crossbars (e.g., single crossbars and double crossbars), and convergent point. (3–7) HT-T5-46-1, VPIGM-4730; HT-T8-12-3, VPIGM-4731; HT-T8-10-3, VPIGM-472; HT-T5-17-1, VPIGM-4733; and HT-T8-1V-1V, VPIGM-4734, respectively. All fossil images are backscattered electron scanning electron microscopy (BSE-SEM) photographs unless otherwise noted. Field collection numbers (prefix HT-) and museum catalog numbers (prefix VPIGM-) are given for each illustrated specimen.

Figure 3. Cambrowania ovata with aperture-like structures, outgrowths, and crossbars that protrude beyond the margin of the fossils. (1–5) Specimens with aperture-like structures (blue arrowheads). HT-T8-9V-8V, VPIGM-4735; HT-T8-25-6, VPIGM-4736; HT-T7-55-1,VPIGM-4737; HT-4-35-1, VPIGM-4738; and HT-T5-55-1, VPIGM-4739, respectively. Inset image in (5) is a close-up view of the aperture-like structure (blue arrowhead and rectangle). Yellow arrowhead marks an outgrowth structure. (6, 7) Specimens with outgrowths (yellow arrowheads) consisting of marginally converging crossbars. HT-T6-58-1, VPIGM-4740 and HT-T8-3-3, VPIGM-4741, respectively. (8) Specimen with crossbars protruding beyond the margin of the fossil (red arrowhead). HT-T4-10-1, VPIGM-4742. RLM = reflected light microscopy photograph. All fossil images are backscattered electron scanning electron microscopy (BSE-SEM) photographs unless otherwise noted. Field collection numbers (prefix HT-) and museum catalog numbers (prefix VPIGM-) are given for each illustrated specimen.

Figure 4. Cambrowania ovata with V-shaped clefts or offset margins. (1–3) HT-T5-23-1, VPIGM-4743; HT-T8-2-1, VPIGM-4744; and HT-T8-1V-7, VPIGM-4745, respectively. (4) Schematic sketch of specimen illustrated in (3). Arrows denote V-shaped clefts or offset margins. All fossil images are backscattered electron scanning electron microscopy (BSE-SEM) photographs unless otherwise noted. Field collection numbers (prefix HT-) and museum catalog numbers (prefix VPIGM-) are given for each illustrated specimen.

Figure 5. Taphonomy of Cambrowania ovata, with evidence for carbonaceous preservation and pyrite formation. (1) HT-T4-11-1, VPIGM-4746. (2) Close-up view of rectangle in (1), showing molds of pyrite framboids. (3) Paratype, HT-T3-8-1, VPIGM-4747. (4) Close-up view of rectangle in (3), showing crossbars of different widths. (5) Close-up view of black rectangle in (4). (6) Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) point analysis at location marked by red circle in (5). (7) EDS elemental maps of blue rectangle in (4). Elements labeled in lower left. SE-SEM = secondary electron scanning electron microscopy photograph. All fossil images are backscattered electron scanning electron microscopy (BSE-SEM) photographs unless otherwise noted. Field collection numbers (prefix HT-) and museum catalog numbers (prefix VPIGM-) are given for each illustrated specimen.

Figure 6. Taphonomy of Cambrowania ovata, with evidence for secondary baritization. (1, 2) HT-T7-30-1, VPIGM-4748, RLM and BSE-SEM photographs, respectively, of the same baritized specimen. Bright area in (2) shows where barite is present. Note that the central part of the specimen [area marked as 3, 4, 7, 8 in (1)] was removed after RLM (1) and before BSE-SEM (2), hence a window of no barite in (2). (3, 4, 7, 8) Cross-sectional view of crossbars removed from marked and labeled positions in (1), showing baritized crossbars and a thin layer of barite [bracketed by white arrows in (3) and (4)] that covers the entire fossil. (5) Close-up view of yellow rectangle in (1). (6) Micro-CT reconstruction of radiating crossbars shown in (5). (9) EDS elemental maps of rectangle in (3), with elements marked in lower left. RLM = reflected light microscopy photograph. All fossil images are backscattered electron scanning electron microscopy (BSE-SEM) photographs unless otherwise noted. Field collection numbers (prefix HT-) and museum catalog numbers (prefix VPIGM-) are given for each illustrated specimen.

Paratype

HT-T3-8-1, illustrated in Figure 5.3, reposited at Virginia Polytechnic Institute Geosciences Museum (catalog number VPIGM-4747).

Diagnosis

A species of Cambrowania with the maximum dimension in millimeter scale.

Occurrence

Shale/mudstone of the middle Hetang Formation in the Lantian area, South China.

Morphological description

Fossils are preserved as discoidal (Fig. 2.1−2.4), subpolygonal (Fig. 2.5), oval to elliptical (Fig. 2.6), and fusiform (Fig. 2.7) carbonaceous compressions that are 1.7–10.7 mm in maximum dimension. Main structures of the fossil include marginal bars defining the outline of the fossil and interior crossbars contained within the fossil (Fig. 2.2). Interior crossbars typically terminate at the margin of the fossil. Multiple interior crossbars can terminally converge at a point on the margin to form a cluster of radiating crossbars (Fig. 2.1−2.3, 2.5). Double crossbars consist of two crossbars that are subparallel and, in some cases, terminally convergent (Fig. 2.1−2.3). Crossbars are 15–94 μm in width and 1–6 mm in length, with broader ones forming blades (Fig. 2.4). Crossbars of different widths can be present in the same specimen (Figs. 2.1, 2.3). Most crossbars are straight (Figs. 2.1, 2.3, 2.5), although some are curved (Fig. 2.3, 2.4) and even twisted (Fig. 2.1, 2.3, 2.5). When the marginal bars are straight, the fossils typically have a polygonal outline (Fig. 2.5).

Some compressed specimens appear to have an aperture-like structure. This structure can be a subtle indentation (Fig. 3.1) or a protrusion (Fig. 3.2−3.5) at one end of the fossil, with the opposite end being round (Fig. 3.1−3.3) or tapered (Fig. 3.5). The aperture, 0.2−0.6 mm in width, gradually transitions to the main body of the fossil (Fig. 3.1−3.4), without a clearly defined boundary such as a constriction. It is possible that the terminal aperture was present in all specimens of Cambrowania ovata but only visible in laterally compressed specimens. Subround to triangular outgrowths, which appear to have developed from convergent points that protruded beyond the margin of the fossils (Fig. 3.5−3.7), are present in some specimens. Occasionally, individual crossbars are found protruding beyond the margin of the fossil (Fig. 3.8).

In addition, a few specimens in our collection (four out of 436 specimens) preserve a medial split (Fig. 4.1, 4.2) that is reminiscent of the ventral margin of the carapace of bivalved arthropods (e.g., Hou and Bergström, Reference Hou and Bergström1997, fig. 20). This split results in a V-shaped cleft, with two hemispherical halves connected on one side and gaping on the other. The gaping margin of the hemispherical halves is defined by marginal crossbars, and apparently no crossbars reach beyond the margin (Fig. 4.1, 4.2), indicating that the medial split may be a biological rather than a taphonomic structure. The gaping angle is 14° to 67°, and butterflied configuration (i.e., gaping angle of 180°; Briggs et al., Reference Briggs, Liu, McKay and Witzke2015) is not seen. Some specimens that do not show a V-shaped cleft appear to have slightly offset margins (e.g., Fig. 4.3, 4.4). It is possible that specimens with V-shaped clefts (e.g., Fig. 4.1, 4.2) and those with slightly offset margins represent taphonomic variants (cf. lateral versus anterior-posterior compression of bivalved arthropod carapace with gaping margins).

Taphonomic description

The crossbars are mostly preserved as two-dimensional carbonaceous compressions, with a few exceptions where they are secondarily mineralized in three dimensions. Abundant pyrite framboids and their molds are present in the crossbars (Fig. 5.1, 5.2), indicating organic degradation through sulfate reduction. The carbonaceous nature of the crossbars is confirmed in EDS point analysis and elemental maps. EDS point analyses show high carbon (C) and oxygen (O) peaks and low sulfur (S), aluminum (Al), and silicon (Si) peaks (Fig. 5.3−5.6), indicating the crossbars mainly consist of organic material. EDS elemental maps confirm the enrichment of C and deficiency of S, Ca, Al, and Si in the crossbars relative to the matrix (Fig. 5.7).

One secondarily mineralized fusoidal specimen has been analyzed in detail (Fig. 6). This specimen is partially covered with a thin barite layer, which is confirmed by BSE-SEM images and elemental maps (Fig. 6.2, 6.9). In cross sections perpendicular to the bedding plane, the barite layer is 10−16 μm in thickness (Fig. 6.3, 6.4). A cluster of marginally converging crossbars occurs at one end of the fusoidal specimen (Fig. 6.5, 6.6), reminiscent of a hexactine-based sponge spicule. It is possible that another cluster occurs at the opposite end, but the crossbars are exfoliated, and only vague imprints are visible (Fig. 6.1). The crossbars are three-dimensionally replicated by barite, and this is clearly seen in a large crossbar running between the two apices of the fusoidal fossil (Fig. 6.1). In transverse cross sections, the baritized crossbars are internally hollow with centripetally growing barite crystals and slightly compressed with a maximum diameter of 180−208 μm (Fig. 6.3, 6.4, 6.7, 6.8).

Etymology

The species epithet is derived from Latin ovatus, referring to the fusoidal to ovoidal shape of this species.

Materials

A total of 436 specimens from shale/mudstone of the middle Hetang Formation.

Remarks

Cambrowania ovata Tang and Xiao, n. gen. n. sp. is morphologically similar to the problematic fossil Chuaria circularis Walcott, Reference Walcott1899 (Tang et al., Reference Tang, Pang, Yuan and Xiao2017) and the carapaces of the bivalved arthropod Iosuperstes collisionis (Briggs et al., Reference Briggs, Liu, McKay and Witzke2015). However, neither of these species has rafter-like crossbars that are interlaced to form a network-like truss, which is the main character of Cambrowania ovata.

Discussion

Morphological reconstruction

Although specimens of Cambrowania ovata are mostly preserved as carbonaceous compressions, three-dimensionally baritized specimens (Fig. 6) indicate that the species was not a flattened organism when alive. Crossbars that radiate from a convergent point are reminiscent of hexactine-based spicules of glass sponges in early ontogenetic stages or of single-rayed oxeas (Fig. 7.1, 7.2); these ‘spicules’ can project beyond the margin of the organism in C. ovata (Fig. 4.8) just as spicules can in modern sponges (Fig. 7.1, 7.2). At least one possible ‘spicule’ is reminiscent of hexactine-based spicules (Fig. 6.1, 6.2, 6.5, 6.6). In addition, the aperture-like structure of Cambrowania ovata is somewhat similar to the osculum of sponges (Fig. 7.3, 7.4). If we interpret these features as spicules and oscula, then we would reconstruct Cambrowania ovata as a spheroidal or ovoidal organism that is similar to the postlarval juveniles of the hexactinellid sponge Oopsacas minuta Topsent, Reference Topsent1927 (Fig. 7; Leys et al., Reference Leys, Kamarul Zaman and Boury-Esnault2016). Alternatively, considering that a few specimens in our collection are preserved with a V-shaped cleft (Fig. 4.1, 4.2) or offset margins (Fig. 4.3, 4.4), Cambrowania ovata may be interpreted as a bivalved organism housed within a carapace similar to those of bivalved arthropods (Briggs et al., Reference Briggs, Liu, McKay and Witzke2015). Mitigating against the arthropod affinity is the fact that only a very small number of specimens have a V-shaped cleft, and thus we cannot completely rule out the possibility that this structure may be a taphonomic artifact (e.g., rupture along crossbars). Therefore, we tentatively favor the spheroidal or ovoidal reconstruction and the sponge affinity over the bivalved reconstruction and the arthropod affinity.

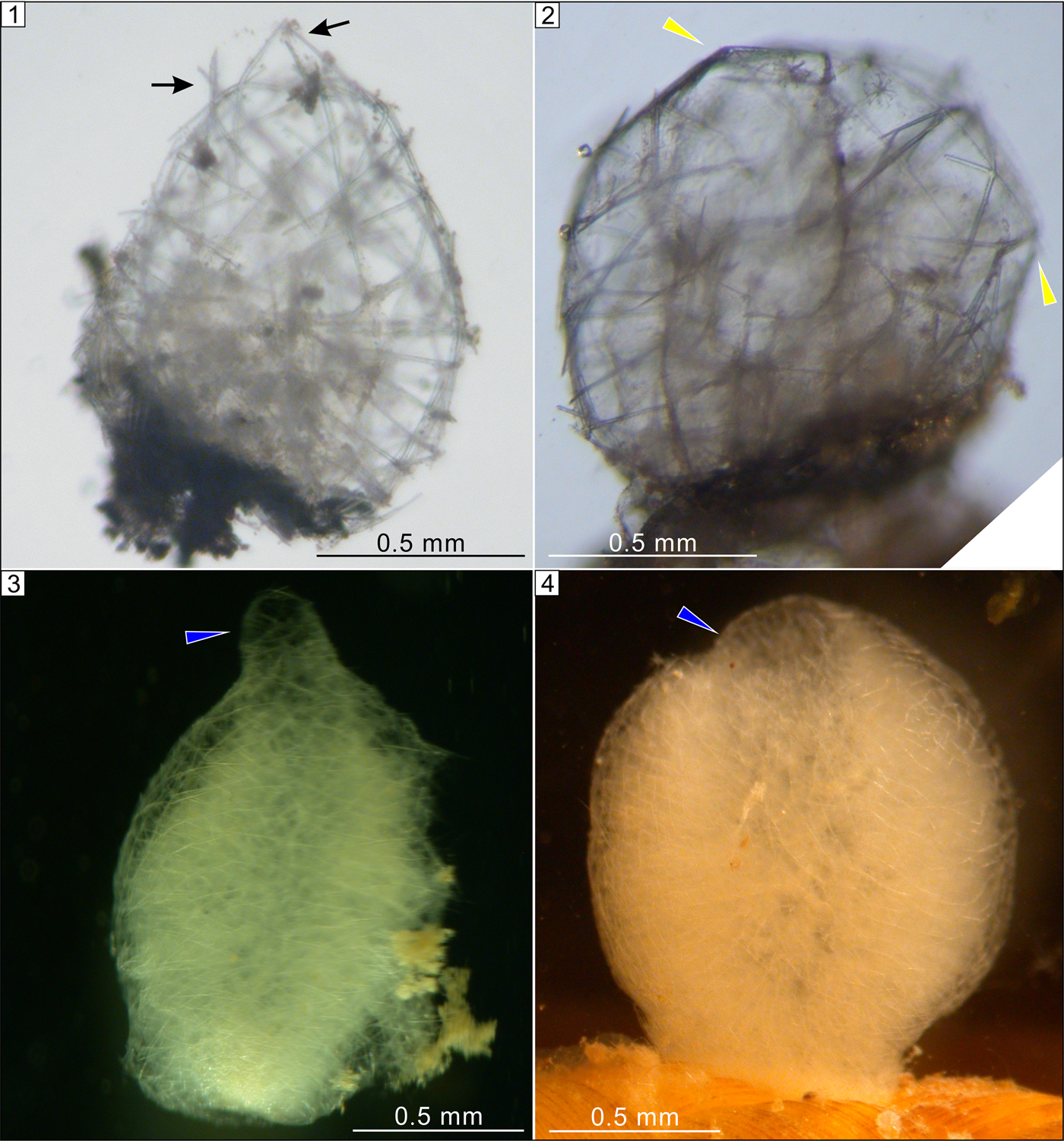

Figure 7. Extant hexactinellid sponge Oopsacas minuta in early life history stages. (1, 2) Spheroidal stage of metamorphosis with protruding spicules (black arrows) and a polygonal outline (yellow arrowheads). (3, 4) Juvenile stage with either a raised or a depressed osculum (blue arrowheads).

Biological interpretation

Although Cambrowania ovata is superficially similar to some algal fossils (e.g., Chuaria) in having spheroidal morphology and organic-rich composition, we are unaware of any algae, fossil or extant, that have hollow cylindrical crossbars similar to those in Cambrowania ovata. In addition, Cambrowania ovata superficially resembles some Cambrian radiolarians (Dong et al., Reference Dong, Knoll and Lipps1997). Indeed, putative radiolarians have been reported from the basal unit of the Hetang Formation (Braun et al., Reference Braun, Chen, Waloszek, Maas, Vickers-Rich and Komarower2007). However, Cambrowania ovata is more than an order of magnitude larger than these Cambrian radiolarians, and it does not have the spherical lattice with radiating spines characteristic of radiolarians. Thus, the following discussion is focused on the possible animal affinities of Cambrowania ovata.

The V-shaped cleft invites a tentative comparison between Cambrowania ovata and bivalved arthropods. Specimens with a V-shaped cleft may represent carapaces of bivalved arthropods, but these bivalved carapaces probably had limited gaping, given the lack of any butterflied specimens in our collection. The strongly irregular traces of organic matter (yellow arrows in Fig. 2.1, 2.5) could be crumples or wrinkles on a flexible carapace due to taphonomic compaction, which are common in high-relief carapaces of arthropods (Fu and Zhang, Reference Fu and Zhang2011; Briggs et al., Reference Briggs, Liu, McKay and Witzke2015). However, the straight and gently curved crossbars of Cambrowania ovata would then likely represent thickened ribs that are structural components of the organism, particularly if their hollow and cylindrical nature, as shown in baritized specimens (Fig. 6), is confirmed in the future.

The crossbars of Cambrowania ovata may represent ornaments (e.g., thickened ribs or ridges) of bivalved carapaces. Many Paleozoic bivalved arthropods have various ornaments on their carapaces, such as reticulate ornaments on the carapace of Tuzoia (Vannier et al., Reference Vannier, Caron, Yuan, Briggs, Collins, Zhao and Zhu2007), striated ornaments on the carapace of Isoxys (Fu et al., Reference Fu, Zhang and Shu2009), and pits on the carapace of Iosuperstes (Briggs et al., Reference Briggs, Liu, McKay and Witzke2015). It is acknowledged that these ornaments are morphologically distinct from the crossbars of Cambrowania ovata, but in principle, thickened ribs or ridges are not unimaginable as carapace ornaments. Indeed, some extant crustaceans can develop reticulate ornaments on their carapaces, with cylindrical ridges somewhat similar to the crossbars of Cambrowania ovata. Polycope reticulata Müller, Reference Müller1894, for example, develops reticulate sculptures with cylindrical ridges forming primary polygonal ornamentation on its carapace (Vannier et al., Reference Vannier, Caron, Yuan, Briggs, Collins, Zhao and Zhu2007).

However, the majority of Cambrowania ovata specimens do not have any trace of a V-shaped cleft, casting doubts on the interpretation of Cambrowania ovata as carapaces of bivalved arthropods. More important, the carapace interpretation is incompatible with many specimens that have a polygonal morphology (Fig. 2.5), an aperture-like structure (Fig. 3.1−3.5), and sharp outgrowths (Fig. 3.5−3.7).

Considering the possible presence of an osculum (Fig. 3.1–3.5) and the morphological similarity between the clustered crossbars and hexactine-based sponge spicules such as pentactines (e.g., those in Sanshapentella dapingi Xiao et al., Reference Xiao, Hu, Yuan, Parsley and Cao2005), it is tempting to consider Cambrowania ovata a spheroidal sponge. Although extant sponge spicules are usually biomineralized (either siliceous or calcareous), some modern demosponges have only organic skeletons (de Cook and Bergquist, Reference de Cook, Bergquist, Hooper, Van Soest and Willenz2002; Hill et al., Reference Hill2013). In addition, many fossil sponges have weakly biomineralized or entirely organic skeletons; these include the demosponge Vauxia (Ehrlich et al., Reference Ehrlich2013) and some protomonaxonids such as piraniids and chancelloriids (Botting and Muir, Reference Botting and Muir2018). Thus, the largely organic composition of the crossbars does not necessarily exclude a sponge interpretation for Cambrowania ovata. Intriguingly, although adult sponges typically have tubular bodies, sponge juveniles tend to be spheroidal in shape. For example, the hexactinellid sponge Oopsacas minuta in the metamorphosis stage is broadly spheroidal with a polygonal outline (Fig. 7.2; Leys et al., Reference Leys, Kamarul Zaman and Boury-Esnault2016) and subsequently develops an osculum in the juvenile stage (Fig. 7.3, 7.4; Leys et al., Reference Leys, Kamarul Zaman and Boury-Esnault2016). The comparison with juvenile sponges is further supported by the presence of a putative osculum in some specimens of Cambrowania ovata (Fig. 3.1−3.5). The V-shaped cleft in a few Cambrowania ovata specimens, if it proves to be a biological rather than a taphonomic structure, seems to contradict the sponge interpretation. However, given that Cambrowania ovata may represent an early ontogenetic stage of sponges (which tend to have a high proportion of organic matter in the skeleton), it is possible that the skeleton of Cambrowania ovata was flexible and the V-shaped cleft might be a taphonomic artifact due to sedimentary compaction.

In summary, Cambrowania ovata is reconstructed as a spherical organism and is interpreted as a possible bivalved arthropod, but more likely it represents an early life history stage of a sponge with a mainly organic skeleton.

Conclusions

The early Cambrian Hetang Formation contains abundant articulated sponge fossils, but it also yields other problematic fossils. This paper describes one of these problematic fossils, Cambrowania ovata Tang and Xiao, n. gen. n. sp., mostly preserved as carbonaceous compressions in the middle Hetang Formation. As preserved, Cambrowania ovata is characterized by a subcircular structure with a network of crossbars that may have been internally hollow. Some specimens have an aperture-like structure, whereas a few have a V-shaped cleft. It is reconstructed as a spheroidal organism. Although we cannot rule out the possibility that Cambrowania ovata may represent the carapaces of a bivalved arthropod, it is more likely a spheroidal juvenile sponge with a mostly organic skeleton. Despite the phylogenetic uncertainty, Cambrowania ovata adds to the taxonomic diversity of the Hetang biota in early Cambrian deepwater environments.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Science Foundation (EAR 1528553), NASA Exobiology and Evolutionary Biology (80NSSC18K1086), National Natural Science Foundation of China (41502010), Geological Society of American, Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, Paleontological Society, and Society for Sedimentary Geology. We thank J.P. Botting and D.E.G. Briggs for discussion, J. Wang for field assistance, and B. Bomfleur and an anonymous reviewer for constructive criticism on an early version of the manuscript. SPL thanks N. Boury-Esnault and J. Vacelet and the staff at the Station Marine d'Endoume, Marseille, France.