In the late third and early second millennia BCE, daily life within the small local communities of Crete likely looked much as it had for many centuries. Familiar, long-standing practices would have lent a steady, recurring cadence to social experience, carried out along well-worn paths and within well-known places. Yet archaeological evidence suggests that persons’ rhythmic activities within these communities did not merely replicate local dynamics ad infinitum, reiterating the contours of a static social world. In the process of engaging in familiar ways of doing social life, people developed novelty in response to fluctuating circumstances, interests and needs. In particular we can appreciate that the relations between communities swelled and complicated at this time, taking on new dimensions of mutuality and comparability. This can be recognized, in part, in the founding of new types of collective place in the landscape that would have been visited by members of numerous smaller communities, such as ritual sites positioned on low mountain peaks and extensive architectural complexes that appear to have been venues for large-scale consumption activities. At such supralocal places, people could gather together beyond the long-established spheres of daily life, forging experiences of communitas at new scales (Turner Reference Turner1969). Events held at these places may have been drawn from the repertoire of social actions long performed within the arenas of local communities, but their reproduction at new scales would have involved considerable reformulation and improvisation. In part, establishing new scopes of collective activity would have entailed practical flexibility and inventiveness as new venues were founded and provisioned. It also would have involved the conceptual, political and ideological work of justifying and negotiating new scales of social similarity – the premise for collectivity, be it cooperative or competitive (see Strathern Reference Strathern1990).

In the pages ahead I consider the implications of the establishment of supralocal “special places” (Lefebvre Reference Lefebvre1991) in the Cretan landscape during the close of the Prepalatial period. Just as important as investigating the events that took place at these locales will be considering the actions that would have occurred as people made their way to and between them; these were the socially saturated movements that actually brought interconnections through the landscape into being. Chapter 4 is dedicated to examination of a particular variety of such socially connective movement, the travels of newly itinerant craftspersons. In the current chapter, I investigate various other types of travel and interaction that set people in motion beyond their small local communities and engaged them in not only new scales but also new varieties of social experience. It was through such activities, subtle and repeated, but also creative and socially significant, that pathways and places in the Cretan terrain became “inhabited” with the lived rhythms of formative regional social space.

We can identify certain developments of the late Prepalatial period that would have had a particularly dynamic influence on the nature of social relation on Crete. These include specific human, material, symbolic and environmental phenomena, ranging from architecture to iconography, from ritual action to patterns of exchange. More than any single factor it is a confluence of changes occurring across these diverse dimensions of lived experience that would have contributed to the shaping of new socio-spatial relations on the island around the turn of the second millennium BCE by altering the character of interaction between communities. Below I outline eight of these key loci of change. This is followed by a more thorough discussion of late Prepalatial social dynamics in which I offer a detailed analysis of two of these contemporaneous phenomena: the founding of large-scale architectural complexes, some outfitted with open courts for gathering, and the establishment of collective ritual sites on low mountains peaks.

Key Areas of Change in Late Prepalatial Crete

[1] I begin in the realm of social ritual, with the foundation of communal open-air sites on low mountain peaks, traditionally termed “peak sanctuaries,” beginning circa EM III. The socio-symbolic significance of these places is reflected in the multitudes of anthropomorphic and theriomorphic figurine fragments that characteristically populate the sites, as well as their dramatic locations high above area settlements, in some cases near fissures or other striking natural features (Soetens Reference Soetens2009). What is less certain is the precise nature of activities that took place at the peak sites, and how they may have varied over the generations of their use (see Peatfield Reference Peatfield, Hagg and Marinatos1987; Nowicki Reference Nowicki, Laffineur and Hagg2001; Morris and Peatfield 2001, Reference Morris, Peatfield and Wedde2004). Some scholars have compellingly argued that during their initial phase of use in late Prepalatial, the significance of peak sites extended beyond their role in religious ritual. They suggest that practices performed at the sites likely included collective political and ideological actions, making them prime venues to query when seeking insight on activities involved in the actual pragmatics of social change. For example, it has been argued that peak sites were a location for events in which power over shifting socioeconomic spheres was negotiated during late Prepalatial, including control over agricultural labor and pastoral territory (Haggis Reference Haggis and Chaniotis1999, Kyriakidis Reference Kyriakidis2006).

[2] A related aspect of social change in later Prepalatial concerns a series of significant developments in economic strategies on the island. Various scholars have hypothesized alterations in this dimension of social life, some working from quite distinct lines of evidence (e.g., Manning Reference Manning, Mathers and Stoddart1994, Haggis Reference Haggis and Hamilakis2002, Burke Reference Burke2010). A phase of settlement expansion has been identified in some regions of the island heading into EM III that involved agricultural exploitation of new areas, such as mountainous zones, as well as a repeated pattern of clustering between smaller interdependent settlements (see Haggis Reference Haggis and Hamilakis2002: 125–129 and forthcoming). Manning sees this period of settlement expansion as the groundwork of increased resource exploitation and wealth accumulation that served as the basis for emerging social differentiation (Manning Reference Manning, Mathers and Stoddart1994, Reference Manning1995, Reference Manning, Nüzhet Dalfes, Kukla and Weiss1997). Meanwhile Burke, examining a specific “industry,” has argued that beginning in EM IIB there is strong indirect evidence that in some places on Crete textile manufacture was increased in order to produce a surplus for export (Burke Reference Burke2010: 29–31). Crucially each of these changes (and others) could have developed as extensions of long-standing local economic activities, which likely would have been amended for new demands and interests, but nevertheless would not have involved radically new practices. This is not to underplay the implications of such socioeconomic developments, but instead to highlight the likely nature of their formation, realization and position within long-standing processes of social life.

[3] As discussion of altering economic strategies makes clear, one must balance identification of overarching social trends in late Prepalatial Crete with close study of specific areas and corpora of evidence. Survey and excavation in the Mesara plain of south-central Crete, a geographical focus of the present work, indicates marked developments in settlement and interaction patterns during later Prepalatial. Based on extensive survey work in the western Mesara, Watrous and Hadzi-Vallianou argue that there were significant developments in settlement relationships beginning in EM II and especially in the subsequent late Prepalatial phase; in the area of Phaistos they see hierarchical center-periphery relations taking form (Watrous and Hadzi-Vallianou Reference Watrous and Hadzi-Vallianou2004: 244–252, Watrous Reference Watrous and Hadzi-Vallianou2004: 253–261; cf. Haggis forthcoming). While not advancing a hierarchical understanding of settlement in the area, excavators working at Phaistos have recently presented remarkable evidence for construction of significant late Prepalatial structures at the site, which they compelling argue would have been the venue for large-scale communal ceremonial gatherings (Todaro Reference Todaro2009a, Reference Todaro2009b, Reference Todaro2013). These studies suggest considerable developments in the scale and nature of lived social engagement in this crucial region at the end of the third and beginning of the second millennium BCE.

[4] Excavation of late Prepalatial structures at Phaistos raises the broader topic of the construction of large-scale building complexes at various locations around the island during this period, often considered to be precursors to the later palaces. Recent studies have shed new light on Prepalatial constructions subtending several of the later palace complexes of the Middle and Late Minoan periods, including those at Malia, Knossos and Phaistos (Pelon Reference Pelon1983, Reference Pelon1999; Wilson Reference Wilson and Day1994; Schoep Reference Schoep2004; McEnroe Reference McEnroe2010; Todaro Reference Todaro2009a, Reference Todaro2013). Where remains are sufficient to form an understanding of underlying architectural phases, it seems that the Prepalatial structures often share key alignments and organizational features with the later buildings, in some cases including the feature of prominent open courts, a defining aspect of Minoan “palatial” architecture.

In identifying and assessing these earlier generations of court buildings, we should not simply push back in time reductive arguments that in effect see emergent social complexity as an inevitable and unproblematic counterpart of such large-scale structures. Instead, we must interrogate the development of this particular form of built space in terms of the activities that it contributed to in later Prepalatial Crete and in the context of other contemporaneous innovations in social practice. Here, too, we have evidence that social relation was being conceived at new scales and in new settings, at what we might term “regional” venues.1 At the same time, the collective events that occurred at Phaistos (and other large-scale buildings) during late Prepalatial likely took their form from familiar types of social action that were performed both previously and contemporaneously within established local-scale arenas on the island, where tombs served as places for communal events (see Branigan Reference Branigan1998a; Legarra Herrero Reference Legarra Herrero2014; Déderix Reference Déderix, Cappel, Günkel-Maschek and Panagiotopoulos2015a, Reference Déderix and Sarris2015b).

[5] Staying with the question of alterations in the scale of social relations, notable shifts in exchange patterns between different areas of the island are evident in the transition into late Prepalatial during EM II. Wilson and Day’s exceptional studies of ceramic imports to Knossos during these phases provide our clearest evidence of such alterations in the dynamics of exchange (Wilson and Day Reference Wilson and Day1994, Reference Wilson and Day1999; Day et al. Reference Day, Kiriatzi, Tsolakidou and Kilikoglou1999; also Whitelaw et al. Reference Whitelaw, Day, Kiriatzi, Kilikoglou and Wilson1997 on Myrtos Fournou Korifi). They have demonstrated that during EM I and IIA, persons at Knossos imported various distinctive wares produced in workshops in south-central Crete. These included fine tablewares that may have been used in collective eating and drinking events at the major northern site, where the vessels’ clearly extra-Knossian origins would have been on display as a vehicle for prestige-building. This usage scenario impels us to consider the possible social and economic dimensions of the long-standing importation of south-central wares to the town of Knossos, a place, already age-old in late Prepalatial, that was likely the locus of considerable collective memory and power (Day and Wilson Reference Day, Wilson and Hamilakis2002). What precisely the imported wares signified in this context will remain difficult to assert, but the value of the vessels likely involved both the distance inherent in their presence at Knossos and the exchange relations that would have moved them from the south to the north of the island.

Taking into account the social dimensions of such exchange, and considering how established the relationships that moved the ceramics from the south likely were by the end of EM IIA, the sudden cessation of this importation during EM IIB is quite dramatic. At that time, Knossos began importing ceramics from eastern Crete instead, notably including the distinctively mottled Vasilike Ware (Wilson and Day Reference Wilson and Day1994, Reference Wilson and Day1999); interestingly, this situation is paralleled in the ceramics repertoire of the small EM II village, Myrtos Fournou Korifi. Naturally we cannot know what the basis of this decisive shift was, which saw the abandonment of one set of relationships and the establishment of others extending into another area of the island. In a general sense, Knossos’ new dealings with eastern parties may have been comparable to those which had long been established with the south, both being based, at least in part, on the importation of distinctive ceramic wares. But these relations were notably reoriented in EM IIB, a change that would have involved novel practical circumstances and social motivations, and hence improvisation and adaptation on the part of those taking part.

[6] The underlying impetuses impelling the reformulation and generation of social relations in late Prepalatial Crete were no doubt fluid and multinature. One potential factor that deserves close consideration is a relatively sudden climate change event that could have had direct and/or mediated effects on social life in Crete. A century-scale event of intense aridification has been detected in paleoclimate proxy data and the archaeological record from elsewhere in the eastern Mediterranean and Near East during this time, beginning circa 2275 BCE and continuing for approximately 250–350 years (Weiss Reference Weiss, Bawden and Reycraft2000: 78–83). The onset of aridification appears to have been rapid, a matter of decades, and extreme, with a 20–30 percent decrease in precipitation in areas of the Near East. It has been argued that this climate event was involved in major social reconfigurations in the region, including dramatic population movements, site abandonments, revision of subsistence strategies and sociopolitical collapse (Weiss Reference Weiss, Bawden and Reycraft2000: 84–89, Reference Weiss, Killibrew and Steiner2014; Cullen and deMenocal Reference Cullen and deMenocal2000).

The effects of this event on the Aegean have not been resolved. Notable alterations in the nature (and decreased archaeological visibility) of social life in areas of the Greek mainland and the Cycladic islands might be connected to abruptly altered climate conditions or to major disruptions in overseas exchange systems involving Near Eastern groups, leading to economic turbulence and collapse (see Forsén Reference Jeanette1992, Watrous Reference Watrous1994, Weiss Reference Weiss, Bawden and Reycraft2000: 89–90, Broodbank Reference Broodbank and Shelmerdine2008: 326, 338). While in some ways the archaeological record of Crete seems to tell a very different story during this time,2 in fact some of the same patterns are visible. Instances of population movement have been identified in later Prepalatial, in some cases characterized by a gathering together of settlement sites, which in certain contexts have been identified as potentially constituting “nucleation.” The formation of such settlement clusters, whether or not they represented nucleated patterns, could have provided groups with more subsistence and social support in a time of environmental change. Likewise, altered subsistence/economic strategies adopted in some areas during this period (discussed above) may have constituted related responses. These developments would have entailed revised and new social practices, involving formative relations between social groups and between people and the landscape. Moreover, such altered lifeways could have contributed to considerable, ongoing sociocultural and sociopolitical effects, something that will be discussed in detail in the pages ahead.

The possibility that a late third millennium BCE climate event had a direct impact on Crete becomes more clearly compelling if one follows Watrous’ reading of the EM III period. He has argued that evidence of a substantive EM III phase in many areas of the island collapses between data from EM II and MM IA, rendering EM III more of a void than a distinct archaeological horizon (see Watrous Reference Watrous1994: 717–720, Watrous and Hadzi-Vallianou Reference Watrous and Hadzi-Vallianou2004: 251–252). Watrous’ discussion is careful and detailed, and deserves close attention. It depends on a combination of settlement and mortuary data and a reevaluation of the dating of certain material corpora, including ceramics and glyptic. For example, incorporating results of his own survey work, Watrous draws together evidence of widespread site abandonment following EM IIB with concurrent evidence that some multigenerational tombs fell out of use. Likewise he has asserted that ceramic and architectural sequences at certain sites should be reconsidered, arguing that they in fact reveal a significant gap between EM IIB and MM IA (e.g., at Gournia, Vasilike; Watrous Reference Watrous1994: 719–720). He connects this evidence of social disruption in the communities of Crete to broader evidence of such in the eastern Mediterranean during this period, and himself indicates that environmental factors could have been involved (Watrous and Hadzi-Vallianou Reference Watrous and Hadzi-Vallianou2004: 267). Whether or not one recognizes the same level of disruption in the archaeological record as does Watrous, the coincidence of data suggesting social reformulation is very significant.

[7] Even if there currently is no consensus concerning whether (or to what degree) the inhabitants of late Prepalatial Crete would have been directly impacted by a late third millennium BCE climate change event, some of the very probable indirect effects could have been quite considerable. To examine this situation we need to evaluate certain changes in the importation of foreign goods over the course of the Prepalatial period. In EM II, Crete was already involved in overseas exchange drawing goods from the Near East and Egypt as well as locations further north in the Aegean. This exchange is clearly illustrated in various distinctive imported objects and materials that have been excavated in EM II contexts, such as Melian obsidian discovered in numerous burials, a hippopotamus tusk from EM IIA Knossos, the gold finery found in tombs at Mochlos and several seals produced either in the Greek mainland or Cyclades that were excavated from the basal level of tholos tomb II at Lebena (see Wiencke Reference Wiencke and Niemeier1981: 259, concerning CMS II1:202, 203; Wilson Reference Wilson, Evely, Hughes-Brock and Momigliano1994: 40; Sbonias Reference Sbonias1995: 80; Carter Reference Carter and Branigan1998; Phillips Reference Phillips2008). Such objects were surely valued on Crete for the physical and social distance that they embodied and the prestige that they could bring to persons with whom they were associated (see Helms Reference Helms1988, Reference Helms1993; Schoep Reference Schoep2006; Colburn Reference Colburn2008; Anderson Reference Anderson and Englehardt2013). In many cases, including Cycladica excavated from EM I–II contexts, preserving the overseas identity of the objects seems to have been important (e.g., obsidian blades deposited in Cretan graves in a manner that appears to imitate Cycladic practices; see Carter Reference Carter and Branigan1998). The possibility that there were Cycladic settlers in areas of northern Crete during early Prepalatial suggests that for Cretans living in this region of the island, the signification of difference occurring through such objects may have been complicated by particular associations. In more general terms, we should likely imagine that the early imports served as a material-symbolic resource with which competing figures or social groups could distinguish themselves, a role that appears to have been repeated, with various cultural inflections, in numerous contexts across the island at this time (Legarra Herrero Reference Legarra Herrero2009). Indeed, even as these imported items were unquestionably rare, they nevertheless are seen frequently enough in EM II levels to presume that they formed a crucial and relatively widespread means of social display and power negotiation.

Closer analysis of certain relevant EM II contexts indicates that the quantity of imports to the island may have dropped off substantially in the course of the period, potentially extending into EM III. At Knossos, for example, Wilson notes evidence of a steady importation of extra-island material in EM IIA followed by essentially no examples dating to EM IIB (Wilson Reference Wilson, Evely, Hughes-Brock and Momigliano1994: 42–43). Similar patterns have been identified elsewhere on Crete (Watrous Reference Watrous1994). The dramatic climate change event identified in Near Eastern contexts circa 2300 BCE may in part be responsible for this, potentially having disrupted established exchange networks running across the eastern Mediterranean basin, both in terms of supply (on the eastern side, if not also the western) and transport. Manning has argued that areas of mainland Greece and especially the Cyclades may have been heavily impacted by the collapse of such exchange networks, given that their economies were more deeply embroiled in them (Manning Reference Manning, Nüzhet Dalfes, Kukla and Weiss1997). Such climate-related factors should be considered in tandem with possible internal social developments that could have involved people in the Aegean choosing to limit their material and social contact with other regions.

While Crete does not appear to have suffered the same level of disruption in socioeconomic processes as that experienced by groups in other areas of the Aegean at this time, external contact and importation of foreign goods to the island did potentially fall off, and this change could have had very real social effects. The value and role of foreign material inevitably would have altered in the face of such disruption, as Crete effectively became more isolated from foreign sources – whether that isolation was imposed or self-motivated.3 In such a context, the embedded meaning, role and identity of foreign finished products and materials would have been revised, so that while certain associations may have been retained by such objects, they also would have taken on new connotations and social value linked to their increased scarcity. In this way social access to foreign signifiers may have become far tighter, thus influencing the signification that such objects embodied. Manning discusses the possibility that a decrease in supply of foreign material culture could have led to a monopoly on those imports already on the island, rendering them a powerful means for asserting social control and prestige between competing social figures (Manning Reference Manning, Nüzhet Dalfes, Kukla and Weiss1997, Reference Manning and Shelmerdine2008). It also appears that during late Prepalatial, less emphasis was placed on maintaining the (perceived) original foreign profile of an object than there had been during the early Prepalatial, with some imported materials now being put to novel uses. Hence the altered valuation of imported material is intimately bound up in the question of developments in late Prepalatial sociopolitical dynamics (see Schoep Reference Schoep2006). As these factors demonstrate, whether effected directly or indirectly, perturbations in the climate and thus in the macroregional system of long-distance exchange likely had complicated, tangible impacts on the lives of Cretan communities at the close of the third millennium BCE. This is one crucial thread to consider when assessing the context of social innovations taking form on the island in late Prepalatial.

[8] Contemplating the changing status of imported material on Crete brings us to the greater topic of material culture’s role in the social changes of the late Prepalatial period. A primary concern of this book is to explore the dynamic ways that objects and materials, the practices that formed them and the activities in which they were engaged, contributed to a significant reformulation of social relation on the island. I discuss various examples of material culture in this light, while maintaining a central focus on a distinctive group of seals dating to late Prepalatial known as the “Parading Lions group,” a name first coined by Yule in his study of early Cretan glyptic (Yule Reference Yule1981: 208–209). This group of seals participated in the innovation of social interactions between people, and between people and the physical world, in multiple ways. The seals belong in part to discussion of foreign materials on the island. Each is fashioned of imported hippopotamus ivory, the origins of which lay in either Egypt or the Levant. Yet the finished seals of this group, which are rendered in a uniform style and stamp-cylinder form, have no foreign counterparts and stand as distinctive, unprecedented Cretan creations. Examples of the seals, and impressions rendered by them in clay, have been found at sites spanning the island, with a concentration of pieces stemming from the well-documented round tholos tombs of south-central Crete. Many of these tombs were repeatedly used and cleaned over multiple generations, rendering their stratigraphy confused and hence making fine-scale dating of materials within the Prepalatial subphases a challenge at best and impossible in some cases. However, thanks in large part to the careful work of Sbonias, we can rather confidently anchor the dating of the Parading Lions group at two points, beginning in EM III and ending in MM IA (see Sbonias Reference Sbonias1995: 89–99).

Tying back into the question of a late third millennium BCE climate change event and disruption of macroregional interaction, the chronological span of the Parading Lions group raises some complicated issues. Crafting of this group of seals, rendered from imported ivory, appears to have begun during a period of very limited foreign importation, EM III. Yet their production (or at least deposition, a distinction discussed ahead) extended into MM IA, when overseas exchange had rebounded considerably. This time span indicates that we should consider the value of the Parading Lions seals as having been fluid, given that access to the ivory from which they were carved may have altered substantially over the period of the corpus’ production and use. Meanwhile, apart from the matter of importation, over the course of the late Prepalatial period the meaning attached to this distinctive group of social objects likely would have evolved as it took on the dimensions of an established tradition on the island, carrying particular sociocultural and perhaps sociopolitical connotations across multiple generations.4 The Parading Lions seals thus stand as exceptional embodiments of the complex social dynamics of the late Prepalatial period, which integrated foreign material and Cretan practice in an innovative material form.

Ivory is not the only imported element of the Parading Lions seals. The eponymous “parading lions,” tiny striding quadrupeds, constitute the principal figures of finely wrought iconographic motifs that were engraved on one of the two flat sealing faces of the seals. The lions are usually depicted in circular chains, accompanied or occasionally replaced by other creatures or design elements. These motifs would have been reproduced as imprints when the seals were stamped in moist clay or a similar substance, which usually was attached to or formed part of another object (e.g., a clay nodule that sealed an object closure, or a jar stopper).

Lions were not native to Crete and there is no evidence suggesting that the beasts were ever present on the island during the Bronze Age. Hence the representation of lions would have been imported, undoubtedly conjuring extraordinary notions in the minds of Cretans concerning the unfamiliar beasts, their nature, origins and meaning. Like the ivory, the engraved lions would have been valued in part for the distance they embodied, which separated the imagined homeland of the beasts from the Aegean island, as well as for other qualities that Cretans associated with the novel leonine figure. The pieces of hippopotamus tusk may even have been understood as the teeth of the depicted lions, which could sink into the moist materials they stamped. Thus, despite initially being imported, the carefully inscribed lions developed a distinct visual form on Crete and surely also took on new meanings. And like the ivory in which it was engraved, the social value of the Parading Lions iconography may have fluctuated over time as it became a more established Cretan phenomenon, and as levels of contact with foreign places altered.

Here we must pause and begin to appreciate not just the novel contents of these fine-scale figural productions, but also the crucial social implications of such production itself. The Parading Lions seal motifs constitute the earliest glyptic iconography on Crete, and arguably the island’s earliest known iconographic tradition of any kind.5 These iconographic motifs stood as a new socio-symbolic form on the island, with real and significant potential to contribute to a reformulation of how persons interacted with one another. Seals carrying the iconography have been found in locations across the island. The development, production and use of the seals thus constituted a widely shared symbolic phenomenon, embodied in highly distinctive material signifiers that were deliberately reproduced at an extralocal and even extraregional scale. The iconographic seals, and the clay impressions stamped by them, accordingly provided an innovative means of asserting sociocultural similarity between persons, and in this way contributed to a broader context of altering social relations on the island during late Prepalatial. The following chapters closely examine the development and crafting of the Parading Lions iconography – the hands and activities that brought it into being, as well as the roles that it played in establishing new varieties of relation between persons who used the seals. What I wish to argue is that in order to appreciate the social effects of these innovative iconographic objects, certain factors should be kept at the forefront of our analysis. In particular, one must: [1] consider the Parading Lions objects as embedded elements within the context of other contemporary changes on the island; [2] recognize the ability of the Parading Lions iconography and style, deliberately shared and reproduced in different locales, to express connections between the identities and actions of people; [3] problematize the crafting of the seals, treating changes that affected the lived processes through which the objects were produced as another rich dimension of social alteration embodied in group; [4] interrogate the lived microcontexts in which seal use involving the Parading Lions objects was performed and [5] recognize that seal impressions, stamped by the Parading Lions seals in clay, were distinct and equally significant socio-symbolic objects, which also contributed to developments in social relation on Crete as they engaged in their own interactive social trajectories, separate from those of the sealer and seal.

Traveling and Gathering: Interaction and Alteration in the Late Prepalatial Landscape

From the turn of the twentieth century CE, understandings of social life and social change on Bronze Age Crete were fixed upon certain unmoving points. The sites of the Middle and Late Bronze Age palaces, Phaistos, Malia and especially Knossos, received immense attention as the hotbeds of “Minoan” society and culture, where power fermented and whence advancements trickled down to the population of the rest of the island. Excavation accordingly focused on these loci and the sometimes spectacular finds they provided to archaeologists. Despite the many crucial and admirable advances made in the process of early archaeological work on Crete, this tunnel vision was selective and isolating, and in important senses uncritical. The “preeminent” status of these places, and the social hierarchy over which they were understood to have ruled, became de facto truths in subsequent scholarship, and their origins were duly searched out in the period preceding construction of the first palaces, the “Prepalatial” period.

Fortunately, and inevitably, this approach has been challenged from various directions. A crucial reframing of social change in later Prepalatial Crete has placed emphasis on the role of interaction. Perhaps the single most important work in this direction, to which many subsequent studies, including the present one, are indebted, is Renfrew and Cherry’s study of peer polity interaction, which examines the processes through which social groups’ being in contact with one another stimulates internal changes in each (Renfrew and Cherry Reference Renfrew and Cherry1986). Since then, numerous scholars have examined specific aspects of the interactive dynamics of late Prepalatial and Protopalatial Crete, with especially rich work emerging from studies of particular corpora of material culture (e.g., Wilson and Day Reference Wilson and Day1994, Knappett Reference Knappett1999, Haggis Reference Haggis and Hamilakis2002, Schoep Reference Schoep2006, Legarra Herrero Reference Legarra Herrero2014).

The fundamental architectural premise that subtends the truism of a palatial emergence has also been challenged by studies that revisit early reconstructions of the first palace complexes and reassess both their accuracy and the assumption that certain architectural features originated with them, en masse (Hitchcock Reference Hitchcock2000, Schoep Reference Schoep2004, Todaro Reference Todaro2009a, McEnroe Reference McEnroe2010); indeed some have asserted that the Cretan palace, and especially the Middle Bronze Age manifestations thereof, are as much modern phenomena as ancient realities (Hitchcock and Koudounaris Reference Hitchcock, Koudanaris and Hamilakis2002, Gere Reference Gere2009). The most disruptive and important contributions in this revisionary vein have demonstrated that large-scale structures, some with built courts (the defining heart of the palace form according to most traditional views) in fact predated the “Protopalatial” MM IB structures at the major palace sites by centuries, their construction traced back to MM IA and EM III levels (or perhaps even EM IIB levels, in the case of Malia) below the later palace structures. Further, these earlier structures, as well as the Protopalatial ones that followed, in fact varied significantly in form from one site to another. Hence we are left with a situation in which there was neither a great palatial revolution in MM IB, nor even a single architectural form to label exclusively “palatial.” Consequently, Schoep has suggested that we utilize an alternative term, “early court buildings,” to describe this heterogeneous group of constructions (Schoep Reference Schoep2004). Moreover, once working outside of the box of “palace sites,” we will also benefit from considering other contemporary venues as part of a broader and more eclectic phenomenon of later Prepalatial built gathering places (Haggis Reference Haggis and Chaniotis1999, Driessen Reference Driessen, Schoep, Tomkins and Driessen2012). The social and conceptual basis of such places likely grew out of earlier (and persistent) forms of locally based collective activity. Yet during Prepalatial these familiar models appear to have flexed and adapted in order to accommodate new scales of social interrelation.

Considerations of Prepalatial collective activity must begin with the venue of built tombs. Funerary behavior and forms have traditionally been understood as elements of community definition and affirmation, and hence as crucial aspects of anthropological inquiry (e.g., Malinowski Reference Malinowski, Lessa and Vogt1958, Aries Reference Ariès1974, Bloch Reference Bloch, Cederroth, Corlin and Lindstrom1988, Hertz Reference Hertz1906, van Gennep Reference Gennep1909, Durkheim Reference Durkheim1912). In studies of Prepalatial Cretan mortuary evidence, attention has typically focused on the prominent and “monumental” tomb types, such as the house tombs of the north and round tholos tombs of south and central Crete (Blackman and Branigan Reference Blackman and Branigan1975, Reference Blackman and Branigan1977, Reference Blackman and Branigan1982; Soles Reference Soles1992; Sakellarakis and Sapouna-Sakellaraki Reference Sakellarakis and Sapouna-Sakellaraki1997; Branigan Reference Branigan1970b, Reference Branigan1998a; Panagiotopoulos Reference Panagiotopoulos2002; Murphy Reference Murphy2003; Alexiou and Warren Reference Alexiou and Warren2004; Papadatos Reference Papadatos2005; Hamilakis Reference Hamilakis2007; Legarra Herrero Reference Legarra Herrero2009, Reference Legarra Herrero2014; Déderix Reference Déderix, Cappel, Günkel-Maschek and Panagiotopoulos2015a, Reference Déderix and Sarris2015b) (Figure 1.1). How the human remains from these tombs reflect funerary practices and negotiation of social identity within Prepalatial communities is debated. Many have associated the tombs with “kin groups,” variably defined as groupings of nuclear families or as collectives of persons linked through other lines of blood and/or social heredity. Numerous scholars have approached the topic by seeking to estimate the total size of populations that utilized a given tomb and their distribution across generations (e.g., Bintliff Reference Bintliff1977, Whitelaw Reference Whitelaw, Krzyszkowska and Nixon1983, Soles Reference Soles1992, Panagiotopoulos Reference Panagiotopoulos2002), or by querying the identity of interred individuals according to demographic factors such as gender and age (e.g., Branigan Reference Branigan1970b, Maggidis Reference Maggidis and Branigan1998, Alexiou and Warren Reference Alexiou and Warren2004). Certainly there are strong grounds for supposing that some Prepalatial tombs were associated with relatively small-scale multigenerational lineages: the occurrence of tombs found in conjunction with isolated farmsteads points in this direction, as do examples whose use spans centuries (see Branigan Reference Branigan1993: 81–95). However we must also appreciate that funerary practice likely varied considerably both within and between Prepalatial communities. Legarra Herrero’s recent study of mortuary data across the island has stressed regional variability not only in tomb form but also at the finer and more nuanced level of social activities and meaning surrounding tomb use (Legarra Herrero Reference Legarra Herrero2009). Within south-central Crete, Relaki has argued that the use of tholos tombs within the Asterousia mountains and Mesara plain should be differentiated (Relaki Reference Relaki, Barrett and Halstead2004). Meanwhile Driessen contends that within Pre- and Protopalatial communities different persons may have received divergent treatments at death, and that the politics of funerary recognition may have varied considerably between sites, even between those in close proximity (Driessen Reference Driessen, Schoep, Tomkins and Driessen2012; cf. Legarra Herrero Reference Legarra Herrero2009, Reference Legarra Herrero2014).

The social significance of Prepalatial tombs encompassed but extended beyond their role as a final resting place for the dead. Déderix’s important work on the cemetery environment of south-central Crete strongly indicates that tombs held a crucial position in the traveled landscape of local communities during the Prepalatial period (Déderix Reference Déderix, Cappel, Günkel-Maschek and Panagiotopoulos2015a, Reference Déderix and Sarris2015b). Focal mobility network analyses suggest that the tombs were located on or near principal pathways that linked the villages of this area of the island (Déderix Reference Déderix and Sarris2015b). In this position they potentially acted as complex social symbols: landmarks that guided travelers between places while also announcing local territorial claims; markers of distinct multigenerational lineages that also, through their common form, testified to elements of shared culture (see discussion in Déderix Reference Déderix and Sarris2015b).

The tombs were also sites of ritual action performed by the living. As places where the remains of generations of community members were interred, and which continually accumulated the residua of further deceased persons (sometimes accommodated through construction of further structures in the same area), the tomb locales were defined by some sense of group identity pertaining both to the amassed dead and to the living who reiterated and maintained their association with a particular place (Murphy Reference Murphy2003).6 Group events of nonfunerary nature almost certainly were staged in these places that would have embodied a core of a community’s collective life (see Driessen’s comparison to “established houses,” Reference Driessen, Schoep, Tomkins and Driessen2012). In the case of the tholos tombs of south-central Crete, which are of particular interest to the present study as they have produced most of the examples of the Parading Lions seal group, multiple tombs were specifically outfitted for such collective actions. At various sites, such as Moni Odiyitria and Ayia Kyriaki, paved areas in front of the tombs defined venues for gathering. Annexes added to some tombs, for example at Platanos and Ayia Kyriaki, appear to have served as ossuaries holding selected skeletal remains that could be given ritual attention (perhaps offerings) without necessitating the opening of the main chamber of the tomb.7 Remains of drinking vessels indicate specific varieties of ritualized consumption. Murphy has read the increased deposition of “mass produced” conical cups at Prepalatial tholos tombs as evidence of a popular funerary-related rite, which she argues may have been manipulated by the elite factions associated with the tombs (Murphy Reference Murphy and Branigan1998).

Working from a different theoretical perspective, Hamilakis has also explored rites of consumption performed at the tholos tombs (Hamilakis Reference Hamilakis2002). He discusses the performance of collective eating and drinking rituals, perhaps in the midst of the (in some cases decomposing) remains of ancestors, as a moment and locus of social definition and cohesion. He describes the social experience of consuming bodies gathered together in the “heterotopic space” (Foucault Reference Foucault1984) of a tholos tomb, a place that was positioned within, and as part of, the broader space of the living community while at the same time being marked out as the realm of the dead. Working in terms close to Turner’s discussion of the ritualized social performance of communitas and “flow” (Turner Reference Turner1982, Reference Turner1969), Hamilakis thus sees the tombs, and the actions that took place in and around them, as having occupied their own space and time. This provided the assembled group with an opportunity to reaffirm their bonds as part of a common social corpus, through eating and drinking together, experiencing altered states of consciousness, engaging in rhythmic movements through dance and percussive sound, and sensing distinctive smells, tastes, visions and textures. Hamilakis uses the term “incorporate” in this context, to describe both the distinctive manner in which persons were engaging with one another as part of a common social entity in a discrete shared space, as well as the individual corporeal acts that were part of this experience as food, drink, sights and odors were brought into persons’ bodies.8 My own use of the term incorporate, developed below, can be connected to Hamilakis’ understanding of it. At the same time, I seek to explore a physio-social phenomenon specific to later Prepalatial social dynamics that involved multiple forms of relational experience that entangled humans, the natural world and material culture. Such activities would have in a sense built upon the type of long-standing collective experiences described so vividly by Hamilakis at Prepalatial tombs.

New Places and New Collective Bodies

During the later Prepalatial period, from EM IIB to MM IA, even as many individual tholos tombs and cemeteries continued in use, novel forms of built space were established that could accommodate collective activity at an expanded scale. The large-scale structures attested below the later palace complexes at Malia, Phaistos and Knossos, as well as constructions at other sites such as Vasilike and Palaikastro,9 can be understood as architectural crystallizations of this moment. While sharing with the tholos tombs the fundamental role of providing discrete spaces for people to gather for shared events, these building complexes and courts constituted novel types of built space with new social motivations embodied in their design and would, in turn, have had different effects on the experience of those gathered. These late Prepalatial structures also would have carried unprecedented associations, quite distinct from those of tombs with their highly localized histories and funerary connotations. The new buildings were extralocal in their geographical and social position, key places within a shared intercommunity landscape that was taking form.

Indications that at least some of the late Prepalatial complexes involved open courts are especially significant. This is not (only) because open courts were a fundamental feature of the later palace structures on the island (and hence the Prepalatial structures may have been their conceptual precursors). The principal significance of the late Prepalatial courts arises instead from the varieties of social action they suggest. A court, most basically understood, is a built space that accommodates collective action, providing a venue free of fixed internal barriers. Yet a court is not simply an empty, generic locale that is passively occupied. Courts delimit the parameters of performed actions and emphasize them in particular ways. With their open design, courts facilitate and even shape the mutual experience of persons gathered within, who can see, hear, potentially touch and smell one another, perhaps as part of specific activities (e.g., in dance, choreographed oration or song, etc.). In fact, far from an empty frame, the openness of courts can be the crucial element in effecting a remarkable flexibility in internal spatial demarcations: objects, furniture, people and beasts can be moved and positioned in a multiplicity of arrangements to create different interrelationships within a defined space. They can also define the boundaries of what or who is included and what or who is blocked out. Moreover, courts can spotlight actions taking place within their borders for viewers located outside of them. A court positioned beside a building façade or wall, overlooked by a balcony or portico, can become an exposed venue of display and revelation. This aspect of courts is characterized on a finer level by the specific details of each: for example, a court deeply embedded within an architectural complex, viewed by spectators along tight angles, with limited air flow and sounds ricocheting off of surrounding walls (or muffled by curtains), would contribute toward a markedly different collective experience than a court positioned on a hillside and open on its edge to a view outward upon the land. Hence while courts share their role in defining and emphasizing collective action, they do so in highly particularized ways, with diverse potential effects. In this light, the built courts of the late Prepalatial stood as distinct and innovative social formulations of space that participated in a recontextualization of collective experience.

The site of Phaistos, located in the Mesara plain of south-central Crete, provides clear evidence of such innovative reformulations of space dating to late Prepalatial. Recent excavations and reassessments of previously excavated material from the site have revealed ten Prepalatial levels subtending the palatial strata, including several dating to late Prepalatial (EM III–MM IA) (Todaro Reference Todaro2009a: 124). In particular, this recent work has clarified that in Phaistos Level VIII, corresponding to EM III, a building project was undertaken which “substantially changed the look of the hill” in the areas of both the southern and western slopes as well as the top of the hill, and which largely defined the fundamental form that the architectural complex would have until the end of the Protopalatial period (Todaro Reference Todaro2009a: 142). This restructuring project involved extensive filling and terracing operations and the construction of buildings with colored plaster floors on various levels, some of which were associated with external paved court areas (Todaro Reference Todaro2009a: 124–125, 136).

The construction of court areas is of particular interest as we consider the provisioning of space for collective activities at the site during late Prepalatial. Subtending the later “palatial” courts (including the areas of the west and central courts of the Middle Minoan palace), layers of pavement have been discovered that indicate that these same places were established as open courts from the moment of the EM III restructuring project onwards. That is, during EM III certain places within the built space of the Phaistos complex were delineated as zones for potential gathering, a role that was retained through succeeding phases, extending into and through the Protopalatial period. This fact highlights late Prepalatial, and more specifically EM III, as a moment of remarkable innovation in the development of Phaistos’ structural and sociocultural identity, characterizing it as a locus of regional collective action.

From the evidence available, it appears that the late Prepalatial complex at Phaistos contained an interpermeating network of distinct venues for gatherings. This was established as part of the major restructuring project initiated in Level VIII. At this time a paved ramp was constructed in the western zone of the complex that extended between (and linked access to) various built areas positioned on multiple levels of the hill. In the south, the ramp appears to have originated from a paved floor subtending Piazzale LXX, extending northward along a circuitous route to ultimately reach another external court area, paved with cobbles, beneath Piazzale I. Along its paved course between these two larger court areas, the ramp provided access to various buildings with colored floors that were situated on different levels of the complex, at least three of which were associated with their own (smaller) external paved areas. Furthermore, from the paved court below Piazzale I, reached at the northernmost extent of the paved ramp, remains of a cobbled passage extending further upslope were found which led to a large, unpaved open area at the top of the hill (Todaro Reference Todaro2009a: 124–125, 142). Far from static and generic venues, this complex of courts and paved areas provided numerous different possible shapes, scales and positions for the experience of collective activities, each with distinct access flows and relationships with other places within the complex, both interior and exterior. Different court areas may have provided different perspectives outward beyond the complex, upon the surrounding landscape with its variable sights, sounds and sensations penetrating inward and outward (e.g., allowing persons to feel a west wind, to view a mountain, stars or sun, or to hear the sounds of wildlife). So too, within the complex, the variable relationship of different areas positioned along the west ramp, between terraces, and within or without walls, would have permitted gatherings in distinct zones to be more or less aware of one another. Hence persons engaged in collective actions throughout the complex could have been closed off from, or in communication with actions occurring in other places, thus constraining or encouraging their movements and experiences along specific physical and social paths at different moments and with different motivations (cf. Lefebvre Reference Lefebvre1991: 93, 99).

While we cannot be certain of the precise nature of the gatherings that took place at Phaistos in the late Prepalatial – activities which motivated the construction of gathering places at the complex and which in turn were shaped by those places once they took form – scholars working at the site have made some fascinating suggestions. Certain areas of the west slope produced evidence of periodic large-scale ceramic fine ware production, leading to their identification as artisans’ quarters. Todaro argues that this material stems from seasonal gatherings of potters who worked communally in paved areas of the west slope to produce ceramics for ceremonial performances taking place in the west court area (Todaro Reference Todaro2009a: 124–125, 141, 142; Reference Todaro2009b). With this suggestion, we can begin to appreciate how the production of novel forms of collective space was entangled with specific varieties of innovative social practice, including the performance of craft. One can imagine the late Prepalatial complex at Phaistos teeming with the bodies of people gathered in discrete areas of the hill and engaging in different manners of collective action simultaneously. The evidence not only indicates the dynamic nature of the Phaistos complex as a venue for formative scales of social experience, but also provides a powerful example of the social dimensions of craftwork (a topic that will be returned to in the chapters ahead).

Todaro contends that seasonal ceremonial events held in the west court of the Phaistos complex during late Prepalatial would have drawn together persons from sites in the surrounding region. Moreover, as evidence of activity in this area of the site extends back to FN strata, she suspects that gatherings may have taken place there already during that early phase in the site’s history (Todaro Reference Todaro2009a: 142, Reference Todaro2009b). If we follow this reasoning, two crucial implications emerge. The first being that by late Prepalatial, Phaistos’ status as a special place in the area of the Mesara plain was already ancient. Secondly, despite this continuity in the site’s esteem, during late Prepalatial the socio-spatial contours of Phaistos were significantly reformulated through the construction projects that initiated Phaistos VIII, effectively recreating its form and hence refining its identity as a place of gathering. These changes were the product of social labor involving the bodies of workers who terraced the hill, cut passageways and paved courts. Whether voluntary or coerced (or somewhere in-between), this labor constituted another variety of collective action that coalesced at the site during late Prepalatial, and stands as another manifestation of the lived practice that supported novel scales of social relation on the island at this time.

According to Lefebvre, such venues of collective action and significance play a crucial role in the process by which social space is produced. In his view, social space “‘incorporates’ social actions, the actions of subjects both individual and collective who are born and who die, who suffer and who act” (Lefebvre Reference Lefebvre1991: 33). The scale of social spaces can vary greatly (more on scale below), from a small village to an entire land, yet in all cases their incorporative nature draws together. Thus social spaces fundamentally involve “encounter, assembly, simultaneity,” wherein that which is assembled includes “everything: living beings, things, objects, works, signs and symbols.” This drawing together focuses on specific points, where the potential for assembly and accumulation is implied, whether or not it is in fact realized (Lefebvre Reference Lefebvre1991: 101). Embedded in this idea is one of the central contributions distinguishing Lefebvre’s work. By recognizing space and social life as being both real and imagined – not as alternatives, but as simultaneous aspects of unified experience – Lefebvre in fact moves beyond both terms. This is the “thirding” of social experience that Soja develops in his notion of Thirdspace, a project that builds on Lefebvre’s work to transcend the familiar structuring binaries of the material and metaphorical, the social and historical, the subjective and objective and so on (Soja Reference Soja1996). Following this, we can see that action, which is inherently spatial, is ever crucial to social reality, but it resides in multifold dimensions of experience – in daydreamings and in manual work, in storytelling and in planning, in the present and in the presently remembered.10

Lefebvre clearly asserts that social space is the “outcome of past actions” (Lefebvre Reference Lefebvre1991: 73). Thus social practice, and more specifically “spatial practice,” brings about or “secretes” social space and, in that sense, precedes it (e.g., Lefebvre Reference Lefebvre1991: 34, 73, 85–86, 101). Yet, as part of a dialogic relationship in which space is produced and space in turn produces (Lefebvre Reference Lefebvre1991: 86), he also describes certain “special places” as being crucial, even “necessary” to the process of creating social space, as they provide active contexts for the negotiation of a social group’s self-definition (Lefebvre Reference Lefebvre1991: 34–35). These are places conceptually marked out in the social landscape, yet steeped in the realized relations of the group(s) in question. Activities undertaken at such places can in turn play essential roles in the ongoing formulation of group dynamics.11 On this point, Lefebvre’s understanding of such special places, and the actions that they see, coincides with Victor Turner’s discussion of “social dramas” – performances enacted by groups that are vital venues for the negotiation of their communal life (Turner Reference Turner1982: 29–47). Turner describes the temporal/spatial moments of social dramas as being embedded in the ongoing “work” of social life, while nevertheless being unique for their role in reasserting and potentially restructuring social bonds. The special places discussed by Lefebvre, like Turner’s social dramas, are not isolated from their broader contexts of social practice and experience, yet stand as singular nodes for the “self-presentation and self-representation” of communities (Lefebvre Reference Lefebvre1991: 34). Activities at these places can evoke moments of the stirring copresence and collective unity that Tuner describes as communitas (Turner Reference Turner1969, Reference Turner1982: 46–47). With time they become symbols of collectivity, laden with social significance born of immediate experience, memories and imaginings alike.

The restructured complex at Phaistos likely would have acted as such a special place in late Prepalatial south-central Crete. It was itself a product of and a venue for currents of developing social practices – the outcome of invested labor and wealth, motivated by the changing needs and desires of the social present. In the Phaistos complex we see a specialized location, fit to certain varieties of collective activity that were carried out at particular moments. At such moments, gathered persons could experience a new scale of social collectivity of which they were part. The activities that took place at the complex, whatever their specific occasion, thus would have acted as instances of self-conceptualization for the assembled, who could perform and formalize their relations within the communal context. Such events, staged within the courts at Phaistos or in other late Prepalatial “special places,” likely entailed socio-symbolic acts involving gathered parties who may have also had other more practical dealings with one another (e.g., exchange relationships, territorial agreements etc.). Hence the collective venues would have accommodated a need to assert and define the existence of a new scale of social relation between members of different communities, and to do so in the presence of one another.12

While it is tempting to interpret the significant changes taking place at Phaistos in late Prepalatial as indications that the site was rising to a preeminent sociopolitical status in the region – as a “political center” in a traditional sense – the particular character of Phaistos’ relationship to other sites at the time remains unclear. Phaistos hill was one of the earliest areas occupied in south-central Crete and, as we have seen, it is likely that gatherings of one sort or another occurred at the site from early points in its history (Watrous and Hadzi-Vallianou Reference Watrous and Hadzi-Vallianou2004, Todaro Reference Todaro2009a). Hence the changes occurring in late Prepalatial did not involve a fundamentally new sociocultural pattern in the area. Yet interpreting finer scale diachronic variations in intersite relationships stands as a crucial challenge. Watrous argues that throughout late Prepalatial Phaistos increasingly developed as a settlement nexus and place of ranked significance in the region (Watrous Reference Watrous2004: 237–244). Haggis, however, asserts that there is no basis on which to see Phaistos’ relationship to smaller neighboring sites as one of hierarchical preeminence or control. He contends that larger villages such as Phaistos may have been “special function sites” and “centers” that were potentially invested with cultural, economic and political significance for the broader population of a region, but that they did not hold sway over settlement (Haggis forthcoming).

It may be that problematizing the “special” status of sites such as Phaistos provides us with the most promising path toward appreciating their distinctive positions in the changing landscape of late Prepalatial Crete. Watrous has proposed that since Phaistos was the original point of settlement in the region, it may have developed and retained its prestige as an ancestral home even as generations of people branched out to establish communities in other locations (Watrous Reference Watrous and Hadzi-Vallianou2004: 255–256). This understanding of Phaistos, as a locus of collective memory, aligns well with the archaeological evidence from the site discussed by Todaro (Todaro Reference Todaro2009a; cf. Day and Wilson Reference Day, Wilson and Hamilakis2002 concerning Knossos). Indeed, approaching the diachronic regional role of Phaistos in terms of memory provides us with an analytical means uniquely apt for considering the significant architectural modifications made there in late Prepalatial. Memory, referring to a past yet a product of a present with its current demands, is mutable and responsive. At the Phaistos complex, we are charged with reconciling centuries of prior activity with deliberate alterations and new constructions on the very same spot – continuity and explicit change are coterminous. In this context, by premising our understanding of the site in terms of memory, we can appreciate how the social character of the place may have been reformulated even as it was reiterated over time, in step with a changing social environment.

If, following Lefebvre, we understand a social space to be specific to a given social moment, with its distinctive dynamics, relations, praxes and interests, then sites such as Phaistos that were occupied over great stretches of time, represent, in a sense, generations of overlaid social spaces – of which one is always the active, realized present: “the space engendered by time is always actual and synchronic – and always presents itself as of a piece” (Lefebvre Reference Lefebvre1991:110). The present space can hold “traces” of old social spaces (Lefebvre Reference Lefebvre1991: 37), visible elements of previous buildings or paths, relational dynamics that persist or are remembered, perhaps in the form of consciously upheld “tradition” (which may or may not accurately correspond to previous ways of doing). Such traces of past social spaces, elements of memory, can be emphasized, hidden or manipulated for present social purposes (cf. Driessen’s discussion of “heirlooms,” Reference Driessen and Pullen2010: 46–47). At Phaistos, it may have been socially and politically useful to assert a physical link to the past by perpetually rebuilding in the same location (and retaining the placement of courts throughout successive building phases). Yet at the same time an attempt was apparently made to control how persons would have understood this trace of previous social spaces by reshaping it for present needs.

In this light, the restructuring of the Phaistos complex beginning in EM III (Level VIII), suggests specific ways that people both responded and contributed to altering community dynamics. In particular, it represents the formalization of spaces dedicated to a larger community of participants, removed from the charged space of the tholos tomb. Indeed the EM III Phaistos complex stood as an innovative manifestation of another scale and type of monumental space, quite distinct from that of the tholoi. It had its own history of social activity extending back to the Neolithic period, and it was upon this past that new spaces took form in late Prepalatial.

Some of the activities that were performed at Phaistos may have been derived from or related to social rites carried out within local communities. Yet the change in scale would not have been a matter of degree alone; with it the nature of the action also would have been transformed.

Hence it is crucial to recognize that during late Prepalatial, the complex at Phaistos (and other comparable places) did not replace the role of local cemeteries – they coexisted in a vibrant social landscape. Late Prepalatial is characterized by a distinct socio-spatial dynamism involving distinct collective locales that saw a variety of actions. At Phaistos we see crucial developments in the structuring of such actions, alterations that took place atop traces of old places and were contemporaneous with events occurring at the long-standing venues of local cemeteries. It is not until the end of MM I that we have indications that places like Phaistos began to take precedence over the local tombs, the latter in some cases being abandoned in a landscape of settlement change (see Déderix Reference Déderix, Cappel, Günkel-Maschek and Panagiotopoulos2015a, Reference Déderix and Sarris2015b).

While my discussion has focused on Phaistos, large-scale architectural complexes and courts were constructed in various other locations on the island in late Prepalatial, including but not limited to the “early court buildings.” These, too, could be investigated from the perspective taken here on the Phaistos complex, considering each for its specific development, shape and implications for social relations in a landscape swelling with interconnections.

Movement and Perspective: Peak Sanctuaries as Nexuses of Social Action

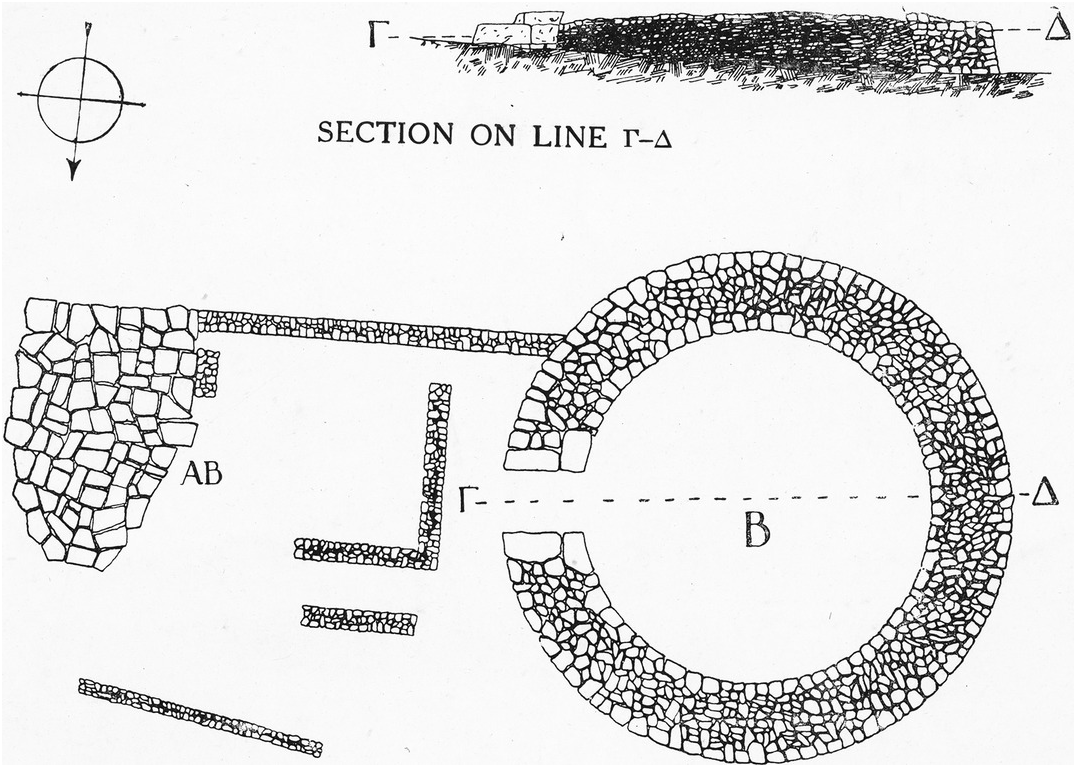

While people gathered in the courts of the restructured architectural complex at Phaistos during late Prepalatial, others ventured high up in the hills and mountains of the island to a new variety of collective ritual site first founded in this period (Peatfield Reference Peatfield1990, Nowicki Reference Nowicki1994, Reference Nowicki, Laffineur and Hagg2001). There has been much discussion and debate concerning the defining attributes of these “peak sanctuaries.” In general, the accepted sites are open air venues located on accessible peaks, marked by the deposition of pebbles, cups, figurines and “votive” material, evidence of gathering, and in some cases built elements (Figure 1.2). They often are associated with distinctive topographical features including dramatic fissures, around which activities seem to have focused (e.g., at Atsipadhes Korakias and Juktas). The relationship of peak sanctuaries to other types of contemporaneous sites is a further point of significant deliberation and some disagreement. Some scholars argue that shrines positioned on lower hilltops, several of Prepalatial date, should be associated with the peak sanctuaries as variants of the same general type of elevated ritual space, for example, the hilltop sanctuary at Ephendi Christou near Phaistos (Peatfield Reference Peatfield1992, Branigan Reference Branigan1998b; cf. Watrous Reference Watrous, Laffineur and Niemeier1995). Meanwhile the relations between the peak sanctuaries and settlements below are central to the assertions of some scholars. Kyriakidis, like Peatfield and others, argues that the view from peak sanctuaries was a defining element of the site type (Peatfield Reference Peatfield1983; Kyriakidis Reference Kyriakidis2006; also Soetens, Driessen et al. Reference Soetens, Driessen, Sarris and Topouzi2002; Soetens, Sarris and Topouzi Reference Soetens, Driessen, Sarris and Topouzi2002; Soetens Reference Soetens2006; cf. Briault Reference Briault2007) (Figure 1.3). In making this assertion, Kyriakidis distinguishes between the “greatest view” afforded from a location, which would be defined by the site’s elevation, merely as a matter of the extent of the viewshed, versus the “best view,” which would instead be a socioculturally determined factor defined by its affordance of perspective upon specific areas of interest below – which might benefit from a closer (i.e., less elevated) vantage point; it is the latter that Kyriakidis argues was a crucial dimension of the peak sanctuaries (Kyriakidis Reference Kyriakidis2006: 21). More specifically, he contends that intervisibility between a peak sanctuary and settlements below was a regular (if not necessarily defining) feature of the sites, a topic considered extensively by Peatfield (see Peatfield Reference Peatfield1983: 276, Reference Peatfield1992, Reference Peatfield2009: 257–259). Kyriakidis crucially expands this topic by considering the possibility of auditory interconnection between a peak site and settlements, in which persons assembled at a peak site would be able to hear sounds – voices, bells, music and so on – produced at lower-lying settlements, and perhaps vice-versa. A given peak sanctuary could have held such visual and auditory links with multiple settlements simultaneously – a topic we will return to shortly.

The connection between settlements and peak sites would have been experienced most immediately as persons made their way from their homes below to the ritual sites “on high.” The particular challenges and sensory experiences that travel to a peak sanctuary entailed would have varied from person to person depending on distance, topography of a given path, one’s physical condition, age and so on. As Peatfield emphasizes, peak sanctuaries were not secluded places separate from local communities, but were prominent points intervisible with them, in some cases associated with particular sites and importantly positioned as elements of a shared supralocal landscape. From a settlement within the region, the pilgrim’s trek likely would have taken a few hours, through the wild and pastoral terrain. One’s path, then, was not intended as a grueling feat to be endured and overcome, but would have been an extended moment of intense, focused engagement with the physical, sensed reality of the region’s environment. In this way, the location of the sanctuaries at higher elevations suggests that “heightened” somatic experiences were sought by travelers. The expenditure and extension of time and effort involved in reaching one’s destination by trudging through the natural and unpredictable terrain of sharp rocks and vegetation, the significant and directly experienced effect of ascending and appreciating an unfolding perspective, and the experience of ultimately achieving a new and reflexive position in the landscape were all potentially important factors in people’s visitation to these places. Intriguing in this light is the deposition at numerous peak sanctuaries of clay objects that appear to be votive body parts that might have served as representative prayer devices for sick or injured persons seeking help from a divine source (Peatfield Reference Peatfield1992: 73–74, with ref. to Myres Reference Myres1902/3). The possibility that people suffering bodily ailments may have regularly made the trek to peak sanctuaries should remind us that the experience of engaging with the path between one’s local community and a regional sanctuary would have been attentive and significant.

In a landscape marked by high contrast between lowlands and mountains, the corporeal experience of approaching an elevated site, and the altered perspective afforded once there, were surely appreciated by people on Crete long before the late Prepalatial period. During the Neolithic period domestic sites were sometimes located on hills and it appears that at certain peak sanctuaries, such as Juktas and Atsipadhes Korakias, some sort of ritual activity may have begun already in EM II or even during FN (Peatfield Reference Peatfield1992, Nowicki Reference Nowicki, Laffineur and Hagg2001). It is during later Prepalatial that we begin to see the wider establishment of peak sites and more compelling evidence for ritual activity. The number of sites founded in this period is an open matter and the challenging and heterogeneous data should remind us that these were complex and fluid places embedded in various sociocultural spheres.13 That said, the increasing number of peak sites and a gradual formalization or typification of their general profile indicate that venues took on distinctive roles at this time or that longer-standing roles began to carry a different social emphasis.14 Here Haggis’ discussion of the emergence of peak sanctuaries as places of ideological power is important (Haggis Reference Haggis and Chaniotis1999). He argues that control asserted by certain persons over ritual actions performed at these venues may have extended into the realm of productive actions, such that power over the ritual domain coincided with command of labor. These figures may have sponsored, led or otherwise mediated collective socio-symbolic activities at the newly established peak sites. As such events likely drew together members of multiple local communities, the scale of power asserted over corresponding productive labor may have also increased, resulting not only in a more integrated sociocultural area but also, potentially, in a greater accumulation of wealth in the hands of a select few. Hence if peak sanctuaries arose as points of ritual life held in common by a broader catchment of communities, the social power enacted and attained at such sites could have likewise been involved in a broadening scope of labor power and integration of production throughout those same communities. Haggis’ argument crucially draws together discussion of actions that occurred within the parameters of the peak sanctuaries with those that took place “below,” that is, actions that formed other elements of community praxis. With this we begin to see these places as parts of developing social spaces, constituted by active social relations that extended into and integrated various locations in the landscape.

Kyriakidis also discusses the possible ideological role of peak sanctuaries, drawing out an important link between this aspect of the sites and their distinctive elevated position. He suggests that the view from a peak site be considered as “commanding,” a term with which he asserts that the perspective afforded by these locations carried with it the potential for holding – or negotiating – power (Kyriakidis Reference Kyriakidis2006: 17, 21). This idea is clearly illustrated with his example of a military guard post being positioned at a peak site, from which one would be able to observe enemies approaching and raise an alert (see also Soetens, Sarris and Topouzi Reference Soetens, Sarris and Topouzi2001; Soetens, Driessen, et al. Reference Soetens, Driessen, Sarris and Topouzi2002). I would build upon this idea to consider how even “friendly” observation from a strategic point implies social control: the mutual gaze of fellow members of a social formation maintains shared norms, and those members who occupy a position from which they can watch more hold a considerable power (cf. Foucault Reference Foucault1975). The perspective attained from a peak site down upon surrounding settlements, the ability to see, hear and when desired to be seen or heard, could certainly have been a factor in the establishment of these sites in late Prepalatial. How that powerful vantage was awarded, shared and utilized could have varied. Its establishment alone, however, as a recurrent variety of place, indicates that something about this view – social as it was physical – gained a more formalized weight in late Prepalatial.

To further explore this notion, I would like to work with another of Kyriakidis’ examples concerning the potential political role of peak sites’ commanding views. In addition to the possibility that they hosted military guard posts, Kyriakidis also mentions that shepherds could have used the vantage point of a peak site to negotiate boundaries for grazing, looking down upon the land below and reckoning something along the lines of, “‘I’ll graze my sheep from that tree to that rock, and you’ll graze yours from that rock to that ravine’” (Kyriakidis Reference Kyriakidis2006: 21). What I find particularly interesting about this insightful example is how, working from it, we can begin to imagine the perspectives offered from these peak sites not simply as the generic view from a high point, but instead in terms of the specific types of things that persons would have been seeing and looking for from such a place – and how they were seeing them.