Introduction: Enlightened Civilization as an Imaginary Space

It would be hard to overstate the significance of the term văn minh or “civilization” in colonial Vietnam between the 1900s and 1920s. It first appeared in Vietnam through the Duy Tân Reform Movement (Phong trào Duy Tân) in the 1900s, which aimed to achieve văn minh khai hóa or the transformation of Vietnam into an enlightened and civilized nation. Its advocates were a group of reformists who were the last generation of Confucian scholars in Vietnam's history and who mostly came from central and northern parts of Vietnam.

When an anti-tax uprising broke out among peasants in central Vietnam in 1908, the French colonial regime blamed Duy Tân participants for encouraging the rebels and swiftly suppressed the movement. Soon afterward, Albert Sarraut, a renowned French radical socialist and a popular, two-time governor-general in French Indochina, proposed a policy of “Franco-Vietnamese collaboration” (Pháp-Việt đề huề). Sarraut likened France to a benevolent elder brother or father who came to Vietnam to enlighten (khai hóa) the local people with civilization (văn minh). He promised that once Vietnam, the little brother or son, was “civilized,” native self-rule would be granted at some unspecified point in the future (Marr Reference Marr1981). The unsettled question of Vietnam's status as a civilized nation was further emphasized in 1919, when the last imperial examination—the test required of all civil servants—included an essay question that asked what it meant to be văn minh and whether (Vietnamese) monarchism was uncivilized (Emperor Khải Định Reference Định1919).

Numerous colonial and postcolonial scholars have examined the discourse of Enlightened Civilization as a hegemonic, universalizing narrative that regulates people's manners (Elias [1969] Reference Elias1994); grants non-Western societies sovereignty only when they meet Western or European standards of nation-states (Duara Reference Duara2001; Gong Reference Gong1984); and offers a new way for people to articulate the relationship between self and society (Bradley Reference Bradley2004). Yet fewer studies have considered what exactly this discourse meant to the “colonized” themselves. In the Vietnamese context, it begs consideration whether “Enlightened Civilization” meant the same thing to the Vietnamese as it did to the French. On the one hand, civilizational discourse was used by the French to justify their overseas imperialist expansion or mission civilisatrice, as Sarraut's characterization of Franco-Vietnamese collaboration above indicates. On the other hand, Vietnamese intellectuals had already dealt with jiaohua/giáo hoá 教化 (literally “educating and transforming”), the Sinitic version of Enlightened Civilization constituted by the knowledge of Literary Sinitic and the sagely texts written in Literary Sinitic, when Vietnam was a vassal kingdom of China. What, then, did it mean for the Vietnamese to be enlightened (khai hóa) into a civilized (văn minh) nation? How did they perceive and engage with France and China's competing discourses of Enlightened Civilization, respectively, while trying to develop their own uniquely Vietnamese văn minh? What did this Vietnamese văn minh look like, and how did it relate to the civilization envisioned by other countries?

This essay examines how the colonial Vietnamese intellectuals who first aspired to transform Vietnam into a văn minh nation through their direct or indirect involvements with the Duy Tân Reform Movement wrote adventure tales and travelogues, among other works, to engage with and reconcile the idealized discourse of civilisation and its jiaohua/giáo hoá counterpart. I argue that these adventure tales and travelogues emerged at a critical moment—one in which Vietnamese intellectuals sought what I call “vernacular modernity” through the translation of Literary Sinitic into quốc ngữ. Quốc ngữ is a Romanized script of the Vietnamese language invented by European Jesuit missionaries in the mid-seventeenth century, and it was hoped that its use would enable Vietnam to quit Literary Sinitic completely and become a truly văn minh nation with its own national literature. Using a strategy I call literary spatialization, Vietnamese authors imagined a space of văn minh constituted of two interrelated spheres: the Rivers-and-Lakes World (江湖; jianghu in Chinese; giang hồ in Vietnamese), and the Peach Blossom Spring utopia (桃源 or 桃花源; taoyuan or taohua yuan in Chinese; đào nguyên in Vietnamese). I offer close readings of three fictional works to show how colonial Vietnamese intellectuals used these spatial tropes as a covert means to critique and escape not only the hypocrisy of the French mission civilisatrice, but also what they saw as the “backward” aspects of their own Vietnamese society and culture. The three works are Nguyễn Bá Trác's Hạn mạn du ký 汗漫遊記 (An idyllic wanderer's travels, 1919–21); Tản Đà’s Giấc mộng con (Small daydreams, [1917] 2002); and Nguyễn Trọng Thuật's Quả dưa đỏ (Watermelon, 1925). In these adventure tales, the authors imagined an alternative version of civilization that rejected neither the French nor the Chinese models, but rather aimed to surpass both by selectively mixing the “best” elements of each with Vietnamese culture.

This article makes two contributions to existing scholarship on colonial subjectivity and discourse. First, in the spirit of highlighting the diverse and multifaceted experiences of paths to modernity, scholars in the field of Asian studies have offered insights into imperial modernity in prewar Japan (Han Reference Han2013), colonial modernity in colonial Korea (Shin and Robinson Reference Shin and Robinson1999), and translated modernity in China at the turn of the century (L. Liu Reference Liu1995, Reference Liu1999). I contribute to this scholarship by examining how vernacular modernity was translated and expressed in the creation of a national literature in colonial Vietnam, which, as many scholars have demonstrated, was a crucial component in modern nation-building projects (Corse Reference Corse1997; Jusdanis Reference Jusdanis1991). Second, while the temporal assumptions and implications of colonial discourse have been intensively scrutinized (Anderson [1983] Reference Anderson2006; Chakrabarty [2000] Reference Chakrabarty2007; Duara Reference Duara1995, Reference Duara2001; Gong Reference Gong1984), less attention has been accorded to its specifically spatial dimensions. When scholars have looked at spatiality, they have done so primarily from the perspective of the colonizer—noting, for example, how Western male adventurers traveled through “anachronistic space” (McClintock Reference McClintock1995) and “contact zones” (Pratt [1992] Reference Pratt2008) to the realm of the Other. In contrast, this essay examines the spatial imagination of Enlightened Civilization from the perspective of the colonized. Colonial Vietnamese intellectuals accepted the colonizers’ perspectives to a certain extent; they wanted intensely to be seen as civilized by the French and felt embarrassed by the “uncivilized” elements of their own society. But at the same time, they also recognized and were resentful of the colonizer's often hypocritical practices. It was, I argue, through a literary spatial imagination that these elites simultaneously expressed their ambivalent desire for and critique of văn minh and its multiple meanings.

Writing Adventure Tales, Translating Vernacular Modernity

The stories I examined here emerged at a critical juncture when translation, vernacularization, and modernization converged for the first time in the Duy Tân Reform Movement in Vietnam. They were written by learned men and long-standing members of the now crumbling Sinographic cosmopolis. The Sinographic cosmopolis was parallel to what renowned South Asianist Sheldon Pollock calls the Sanskrit cosmopolis—a translocal political-cultural world order in which the Sanskrit provided the ruling elites with a code of literary and political expression, as well as a basis for a politics of aesthetics. This cosmopolis came into being around 300 CE when Sanskrit, as the language of the gods, spread from South Asia to many polities in mainland and maritime Southeast Asia; and it began to disintegrate around 1300 CE, when local forms of speech were dignified as literary languages and rose to replace Sanskrit (Pollock Reference Pollock2000, Reference Pollock2006). The Sinographic cosmopolis similarly connected learned men in Vietnam, Korea, Japan, and China through shared knowledge of Literary Sinitic and jiaohua. What differentiated the Sinographic cosmopolis from its Sanskrit counterpart was that Literary Sinitic was used more broadly: learned men and rulers in East Asia used it not only in literary communication but also in administration. In addition, vernacularization took place much later in the Sinographic cosmopolis: only when China's hegemonic position in Asia was challenged by the West in the latter half of the nineteenth century did learned men across East Asia begin to see their native tongues and vernacular scripts as a crucial part of the modernization project (Pollock Reference Pollock2006).Footnote 1

In the case of colonial Vietnam, vernacularization and the pursuit of văn minh took place in the early twentieth century as learned men became aware of East Asia's power transferring from the weakening Qing China to Meiji Japan through Chinese sources that were influenced by or plagiarized from Japanese texts. Thanks to these writings, colonial Vietnamese scholars learned of Japan's successful Meiji Renovation in 1868 and Qing China's short-lived Hundred-Day Reform Movement in 1898, itself a failed imitation of the Meiji Renovation. Inspired by both movements as they were discussed in Chinese reformist writings, similarly reform-minded Vietnamese scholars created the Duy Tân Reform Movement and introduced the ideal of văn minh khai hoá, the Vietnamese rendition of the Chinese term wenming kaihua, which was translated in turn from bunmei kaika, the slogan of the Meiji Renovation. The Duy Tân Movement sent more than two hundred Vietnamese youths to Japan to learn the secret to Enlightened Civilization, an effort dubbed the “Voyage to the East” (Đông Du) Movement. Some leaders, too, stowed away to Japan, including some authors of the stories. But contact between colonial Vietnam and contemporary Japan was short-lived, for in 1908 Japan made an agreement with France to expel the Vietnamese students in exchange for trading privileges in Indochina.

Western ideas translated by Japanese thinkers continued to arrive in Vietnam, but they did so indirectly—via the medium of Chinese sources, which were translated from Japanese texts and known as “new books” (tân thư) in Vietnam (Đinh Xuân Lâm Reference Lâm1997). The most influential Chinese new books were those by Kang Youwei (1858–1927) and his student Liang Qichao (1873–1929), the leaders of the Hundred-Day Reform Movement. Both Kang and Liang went into exile in Japan after the movement was crushed by Qing China and then traveled, trying to raise funds for further organizing. Both men wrote political and social texts introducing Western thoughts and ideas, as well as travelogues that sought to highlight models and examples for China to follow.

The Duy Tân activists freely borrowed and improvised on Chinese reformist writings both to effect a complete break from Literary Sinitic and to criticize Confucian learning and precolonial literature for losing touch with two realities: one, the rapidly changing world; two, the Vietnamese reality that was absent in most of the precolonial literary works written in Literary Sinitic, in which the authors extoled Chinese scenes but turned a blind eye toward their own society. To repair the damage done by Literary Sinitic and ensure Vietnam's survival, Duy Tân activists advocated the replacement of Confucian learning by “practical learning,” a solution also proposed by Chinese reformist writers. In Văn minh tân học sách 文明新學策 (The strategy of civilization and new learning, [1904] 2010), the manifesto of the Duy Tân Movement, the activists urged their fellow Vietnamese to stop admiring Literary Sinitic at the expense of “our national script” (chữ nước ta) but to view the former as simply one of many national scripts with which “our national script” enjoyed equity. By elevating Vietnamese vernacular language to the national language while demoting Chinese from its previously privileged status, colonial Vietnamese intellectuals sought to establish what Lydia Liu (Reference Liu1995, Reference Liu1999) calls the hypothetical linguistic equivalence between the two languages. This equivalency was utterly unthinkable in precolonial Vietnam, when learned men used the Chinese-based vernacular Nôm script as a pedagogical tool to facilitate the learning of terms and texts written in Literary Sinitic (J. Phan Reference Phan2013).

By providing the ontological foundation for the translation from Chinese into quốc ngữ, Sino-Vietnamese linguistic hypothetical equivalence facilitated the process of vernacularization, which was crucial for the establishment of a national literature. While colonial Vietnamese intellectuals insisted that quốc ngữ was indispensable to the survival of Vietnamese nation, they also emphasized that translating Chinese would help enrich Vietnam's vocabulary and strengthen its expressive power. Paradoxical as this may seem, it was a necessary strategy given the relatively sparse literary materials Vietnamese scholars had to work with in order to construct a national literature. Though precolonial Vietnamese literati took pride in Vietnam's status as a “domain of manifest civility,” the rich textual tradition, vibrant printing business, and thriving mass consumption of literature found in other East Asian societies such as China, Japan, and Korea simply did not exist in precolonial Vietnam (DeFrancis Reference DeFrancis1977; McHale Reference McHale2004). The most developed precolonial literary works were written in Literary Sinitic. As a result, imitating other countries’ literature through translation so as to build a foundation for the development of Vietnam's national literature was a feasible solution; translated Chinese fictions, especially historical novels and fantasies, were flooding colonial Vietnam's emerging quốc ngữ reading public (Yan [1987] Reference Yan and Salmon2013). Western literature was also translated into quốc ngữ largely from Chinese translations, which in turn were very likely translated or plagiarized from Japanese (Trần Ngọc Vương and Phạm Xuân Thạch Reference Vương, Thạch and Lân2000).

It was not until the 1930s that vernacular prose fiction in Vietnam was mature enough for intellectuals there to feel they could reduce their heavy reliance on translation, especially works translated from Chinese; further, by this point there existed a critical mass of readership literature in quốc ngữ. The Self-Strengthening Literary Group (Tự Lực văn đoàn), Vietnam's first literary group, founded in 1932 by several famous Westernized intellectuals, established as its first tenet: “We will produce books with literary values with our own labor. We won't just translate foreign books with only aesthetic values. Our goal is to enrich the literary legacy of our nation” (Tự Lực văn đoàn [1934] Reference văn đoàn and Nguyễn Cừ2006).

It was in this context of vernacularization and modernization through translation that the authors I discuss here were inspired by the Duy Tân Movement to write their adventure tales and travelogues. Growing up, these authors were trained in Chinese learning in preparation for the imperial examination. The lower-level examinations ended in Tonkin in 1915 and in Annam in 1918, and the examination system concluded entirely with the palace examination of 1919. (It was abolished in the South in 1864.) As a result, they were most comfortable reading and writing in Literary Sinitic. They were avid readers of Kang Youwei and Liang Qichao's works, and their own literary output should be considered part of what Karen Thornber (Reference Thornber2009, 2) describes as “the literary contact nebulae”—the transcultural engagements with Japanese literature by writers and translators from semicolonial China, colonial Korea, colonial Taiwan, and occupied Manchuria, where the influence of Japan's newly established intellectual authority was keenly felt, even though Vietnam at the turn of the century was under French rule.Footnote 2 Some of these Vietnamese authors shared the experience of actually escaping French pursuit and stowing away overseas; others were familiar with such experiences through the accounts of their comrades and friends or those that appeared in Kang Youwei and Liang Qichao's works, among others. After the Duy Tân Movement ended, their accounts of these experiences became the stories I analyze in this article.

Why did those who survived the French suppression choose to write about their experiences in the literary forms of adventure fiction and travelogue? A review of both Vietnam's first theoretical treatment of fiction by Phạm Quỳnh (1892–1945) and The strategy of civilization and new learning reveals that, prior to the 1930s, colonial Vietnamese intellectuals believed that the popular genre of adventure fiction provided the fastest and most efficient means to both accomplish literary vernacularization and cultivate a modern Vietnamese people. Adventure fiction as a genre started with English writer Daniel Defoe's classic Robinson Crusoe in 1719, the pioneer of realism and the first modern fiction. Characterized by its commitment to factual details and descriptive language, realism was believed by colonial Vietnamese authors to be capable of curing the “disease” of aloofness that was rampant in precolonial literature. While their predecessors considered composing poems in Literary Sinitic to applaud beautiful scenes in China, a tasteful display of their giáo hoá, colonial Vietnamese intellectuals rebelled and questioned their predecessors’ devotion of so much ink to places that no Vietnamese—not even the poets themselves—had ever visited. Colonial Vietnamese scholars also felt that realism, as a literary style, was straightforward, and would be relatively easy for the young and still growing quốc ngữ to imitate (Phạm Quỳnh Reference Quỳnh1921). Better yet, Phạm Quỳnh reasoned, both the would-be writer and the reader were well-prepared for Western adventure tales, not only because of the universal human traits of curiosity and adventurousness, but also because the Vietnamese reading public had already immersed themselves in Chinese historical novels, which contained plenty of adventurous elements and enjoyed tremendous popularity during the colonial era (Phạm Quỳnh Reference Quỳnh1921). Phạm Quỳnh's view about how human curiosity made readers receptive to adventure tales was echoed by Thiếu Sơn, a French-educated young intellectual who published a well-known literature commentary in the 1930s (Thiếu Sơn Reference Sơn1933).

Colonial Vietnamese intellectuals thus seemed to agree with Phạm Quỳnh's observation that composing adventure stories in quốc ngữ would be a less daunting task than pursuing other literary genres, such as detective novels. Japanese and Chinese reformist intellectuals had started to translate Western detective novels in the 1890s and subsequently tried their hand at creating their own versions by the 1920s. Their hope was that their readers would learn logical and scientific thinking by observing how Western detectives solved crimes. Arthur Conan Doyle's iconic figure Sherlock Holmes and Edgar Allan Poe's works were extremely popular in both Japan and China starting in the late nineteenth century (Hung Reference Hung and Pollard1998; Igarashi Reference Igarashi2005; Kawana Reference Kawana2008). While Chinese-translated detective novels were popular in colonial Vietnam—the protagonists of two of the twelve stories under consideration here claimed to be able to detect someone spying on them, thanks to detective novels (Nguyễn Bá Trác Reference Trác1919, Nam Phong 24:219; Phan Bội Châu [1925–26] Reference Châu, Qinghao and Xun2010, 254)—there seemed to be no interest in writing detective novels in quốc ngữ during the colonial era. Indeed, the first Vietnamese-authored detective fiction, written by Phạm Cao Củng, had to wait until the latter half of the 1930s to appear.

In addition to the fact that adventure tales were relatively easy for aspiring Vietnamese authors to imitate with quốc ngữ, intellectuals believed that developing a tradition of travel writing and reading adventure tales would help to advance Vietnam's level of văn minh. The colonial era was a time when both intellectuals and educated youths were curious about the world and interested in “rediscovering” their own home country, as it became increasingly embedded in the world via French colonialism. They were enthusiastic about tourism, travel, and opportunities to observe their native land from new perspectives (Nguyễn Hữu Sơn Reference Sơn2007). Travel writings, whether by Vietnamese writers, Chinese reformists, or Western authors, left a long-lasting impression on colonial Vietnamese readers (Phạm Quỳnh Reference Quỳnh1923). Furthermore, the connection between adventure tales and Western imperialist expansion has been eloquently argued by many scholars of Western literary history (Butts Reference Butts and Hunt2004; D'Ammassa Reference D'Ammassa2009; Dawson Reference Dawson1994; Green Reference Green1980), and this link certainly did not escape Vietnamese intellectuals at the time. They saw Western travel tales as the embodiment of adventurism, the driving force that was thought to give rise to Western imperialist expansion. In The strategy of civilization and new learning (Tản Đà [1904] Reference Đà and Thâu2010, 213) and other intellectual writings (Hoa Đường [Phạm Quỳnh] Reference Đường1924; Phạm Quỳnh Reference Quỳnh1922, 433; Reference Quỳnh1923, 80), Europeans’ love of travel and adventure was seen as driving the progress and promulgation of Western civilization. In “The origins of a society,” the first chapter of Quốc dân độc bản 國民讀本 (The reader for the nation), also published by the Duy Tân activists aiming to mold Vietnam into a văn minh nation, the anonymous authors used Robinson Crusoe as an example to argue that a society founded upon collaboration and civilization advanced as a result of the spirit of independence (Tản Đà [1907] Reference Đà and Thâu2010, 343, 381).

The Tropes: The Rivers-and-Lakes World and the Peach Blossom Spring

I have located twelve adventure tales and travelogues written in both Chinese and quốc ngữ by seven Duy Tân writers. The authors envisioned two recurring spatial tropes for văn minh: the Rivers-and-Lakes World, and the Peach Blossom Spring. Both are literary tropes that were well known among premodern East Asian literati. The term “rivers and lakes” is a potent metaphor in Chinese and Vietnamese societies that refers to a web of interpersonal relationships among exiles from the control of state. As late as the fourteenth century, the symbol of rivers and lakes denoted a fraternal realm of risks, uncertainty, and even criminal activities. The literary evidence can be found in Shui hu zhuan 水滸傳 (Water margin), one of the four classics of traditional Chinese fictions that tells the tale of Song dynasty outlaws who formed a formidable army in the rivers and lakes, eventually won amnesty from the government, and went on a campaign to resist foreign invasions and suppress local rebels. That such stories existed in folk tales indicates the popularity of the rivers-and-lakes metaphor for centuries before being formalized in manuscripts in the fourteenth century.

Since then, the Rivers-and-Lakes World has become one of the most favored settings in Chinese popular literature, especially historical fantasies, martial arts fantasies, or a combination of both. In this imagined world, unusual figures come together to form sworn communities, sects, clans, and schools of martial arts. The world has its own laws: when conflicts or disputes arise, they are often resolved using force and presided over by an arbiter of justice, who is usually both a respected xia 俠 (the honor code, knight or chivalry) and a superb martial artist of noble character. The Confucian ethics of loyalty, righteousness, and benevolence are emphasized. The inhabitants, who are “stateless subjects,” depend on each other to survive persecution from the allegedly law-abiding world, where courts are dysfunctional, bureaucrats corrupt and self-seeking, and injustice rampant (P. Liu Reference Liu2011).

The origins of the rivers-and-lakes trope in China and its appearance in Vietnam are difficult to trace, but historical and literary evidence shows that the meaning of Vietnamese giang hồ is very similar to that of Chinese jianghu, if not identical. It is likely that the idea was popularized in colonial Vietnam via translated Chinese historical and martial arts fantasies that were flooding colonial Vietnam's burgeoning quốc ngữ reading public in the early 1900s (Yan [1987] Reference Yan and Salmon2013). A survey of early dictionaries shows that the term had an entry in 1930, which defines the implication of giang hồ as “people who drift around.”Footnote 3

The metaphor of the Peach Blossom Spring is an even more potent symbol. It is found not only in literature, but also in drama, paintings, music, dancing, and even popular Taoist belief systems in Chinese communities within and beyond China (Bokenkamp Reference Bokenkamp1986; Shafer Reference Shafer1986; Shi Reference Shu-Qian2012). In East Asia, in both high culture and popular culture, the Peach Blossom Spring signifies a Confucian Shangri-La where happiness and peace exist in place of war and strife. Both the Rivers-and-Lakes World and the Peach Blossom Spring exist outside of a disappointing state and evoke utopian connotations, yet they also differ significantly. While the Rivers-and-Lakes World is a complex underground society inhabited by extraordinary people exiled from regular society and seeking to restore the Confucian order, the Peach Blossom Spring is a magical world of perfect tranquility populated by immortals and glimpsed only briefly by fortunate mortals.

The story of the Peach Blossom Spring began as an oral folk tale made famous by the fifth-century poet Tao Yuanming (365–427), who resigned from his humble administrative post rather than allow his integrity to be compromised by a lowly, poorly paid job. In Tao's written version, a fisherman discovers the hidden utopia by accident and is shocked to find a blissful realm of plenty, devoid of the turmoil besetting the outside world. The contented inhabitants are friendly, but ask that the fisherman keep the place a secret. The fisherman breaks his promise, but efforts to find the place again are futile. Once Tao Yuanming put this oral tale into writing, the metaphor of the Peach Blossom Spring flourished in a number of artistic styles and literary subgenres. Variations developed in both China and Vietnam. For example, subsequent tales often featured beautiful maidens inhabiting the Peach Blossom Spring and marrying the protagonists who, nonetheless, eventually have to leave; others emphasized the slower passage of time within the discovered paradise.

The different emphases and elements of the two tropes notwithstanding, the Rivers-and-Lakes World and the Peach Blossom Spring in the three stories discussed here served to highlight and critique the chaos and corruption of existing society, and imagine instead the ideals that would lead to văn minh.

The Stories: Idyllic Wanderer's Travels, Small Daydreams, and Watermelon

Vietnamese authors of adventure tales and travelogues employed the tropes of the Rivers-and-Lakes World and the Peach Blossom Spring to spatialize their experiences of and imagination about travel and adventure while exiled outside of state, to express their yearning for and discovery of văn minh, and to advance their nationalist effort to glorify their home country. Of the twelve stories, eight related giang hồ experiences that were full of dangers and suspense, but also often sweetened by the protagonists’ bonding with likeminded revolutionaries from other Asian countries that, like Vietnam, were striving for independence. The most representative work of this subgroup was Nguyễn Bá Trác's Idyllic wanderer's travels. This story was a huge hit, and shortly after it appeared in Chinese, Nguyễn Bá Trác himself translated it into quốc ngữ. Famous Duy Tân leaders Phan Bội Châu and Phan Chu Trinh also found this theme appealing. Phan Chu Trinh's work offers a particularly clear example of how translation facilitated vernacularization in colonial Vietnam. His six-eight metered verse story, titled Giai nhân kỳ ngộ (The ballad of wonderful encounters with the beauties), was a reworking of Liang Qichao's novel Jia ren qi yu 佳人奇遇 (Wonderful encounters with the beauties) [in 1898, itself a loose translation of Meiji thinker Shiba Shirō’s political novel of the same title (Kajin no kigū 佳人之奇遇) published between 1885 and 1897. Shiba Shirō’s extremely popular political novel, in turn, was inspired by scholar-beauty genre fiction that had long been popular in China, Korea, and Vietnam but had only recently caught Meiji writers’ attention (Sakaki Reference Sakaki2000). Phan Chu Trinh got to know this work in Chinese translation through Liang Qichao's Collected essays from the ice-drinker's studio (1902), one of his favorite works, and reworked it into quốc ngữ while he was exiled in Paris, but he never finished it (Vĩnh Sính Reference Sính and Trinh2005).

The second-largest group of stories—three out of twelve—highlighted what an ideal Peach Blossom Spring utopia should look like once humanity found a way for peace and progress to coexist. Two of these were authored by Phan Bội Châu in Chinese to express his disillusionment with Enlightened Civilization, but the most popular one was Tản Đà’s semi-autobiographical Small daydreams (1916), which related how the protagonist—that is, Tản Đà himself—stumbles upon a Confucian-utopian Peach Blossom Spring văn minh while traveling the world. Its popularity was such that Tản Đà went on to publish Small daydreams II in 1932 and Big daydreams (Giấc mộng lớn) in 1933.

Finally, in 1925, Nguyễn Trọng Thuật rewrote a short Vietnamese legend Tây qua truyện 西瓜傳 (The tale of watermelon) into a Vietnamese version of Robinson Crusoe, in which a Confucian sage is exiled in a stateless Rivers-and-Lakes World but manages to civilize a deserted island into a Confucian Peach Blossom Spring utopia. His accomplishments were such that he inspired awe among high-profile Chinese scholar-officials. Watermelon was not widely read, but soon after it was published, it won the first quốc ngữ novel contest held by the Association for Intellectual and Moral Formation for Vietnamese (in French, l'Association pour la Formation Intellectuelle et Morale des Annamites; in Vietnamese, Hội Khai trí tiến đức), a Francophile institute and a cultural arbiter of the colonial regime.

Searching for Văn Minh in the Rivers-and-Lakes World: Nguyễn Bá Trác's An Idyllic Wanderer's Travels

An idyllic wanderer's travels is a revolutionary romance about a Vietnamese youth—i.e., the author Nguyễn Bá Trác (1881–1945) himself—who finds himself in a transnational Rivers-and-Lakes World brought into being by the revolutionary and anti-colonial activities spreading across East Asia in the early twentieth century. In China, between the late 1890s and the early 1900s, the symbol of the Rivers-and-Lakes World became increasingly associated with revolutionary activities. Depicted as a secret fraternal society seeking to restore the Confucian justice thwarted by some bad elements in a state, the Rivers-and-Lakes World provided a powerful discursive tool to represent and rally anti-state rebellions. This was so because of the Republican Revolution that overthrew the rule of Qing dynasty and established the Republic of China in its place in 1911: the revolution's leaders not only recruited and mobilized many secret societies to join their uprisings, but also explicitly modeled their revolutionary organizations after the rivers-and-lakes societies depicted in literature (Duara Reference Duara1995). In the late nineteenth century, due to the Qing suppression, quite a few Chinese members of the anti-Manchu Heaven-and-Earth Society (Tiandi Hui 天地會) were exiled to Southeast Asia, including Cochinchina, where they inspired Vietnamese patriots and bandits to form a Vietnamese Heaven-and-Earth Society (Thiên địa hội) for mutual aid and anti-colonial activities (Sơn Nam Reference Nam2003). Phan Bội Châu, the most respected Duy Tân leader of clandestine activities and also an author, was keenly attuned to the Chinese political situation and modeled several revolutionary societies after those involved in the successful Republican Revolution. He hoped that these secret-society-like organizations would stir up revolution in Vietnam and eventually replace the French colonial state with an independent Vietnamese national one.

Nguyễn Bá Trác was a successful candidate in the provincial level of the imperial examination, and one of the two hundred Vietnamese youths who answered the call for Duy Tân by participating in the Đông Du Movement. In the preface, he claimed that he wrote the story to remember his travels, study, and adventure in Siam, Hong Kong, Japan, and China between 1904 and 1908 (Nguyễn Bá Trác Reference Trác1919, Nam Phong 22:149–50). Nevertheless, a close examination of the story reveals that the author sprinkled his memoir lavishly with news reports and rumors about trans-Asian revolutionary activities and figures in order to increase the story's suspense. His comments on the culture, history, and society of the countries he visited resembled many contemporary Chinese travelogues, most notably Kang Youwei's Ouzhou shiyi guo youji 歐洲十一國遊記 (The travelogues of eleven European countries, [1905–8] 1985) and Liang Qichao's Xin dalu youji 新大陸遊記 (The travelogues in a new continent, [1903] 2007), in which the two authors described the countries they visited in great detail and combined their own observations and comments. Nguyễn Bá Trác, too, integrated information about the history, geography, races, and culture of the countries he visited in order to give his work an aura of authenticity and satisfy readers’ curiosity about the outside world.

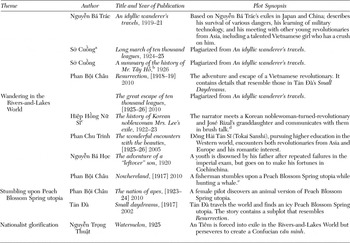

Table 1. Colonial Vietnamese Adventure Tales and Travelogues

Notes:

a Sở Cuồng is the penname of Lê Dư, the brother-in-law of prominent scholar Phan Khôi. “Sở Cuồng” is the Vietnamese rendition of Chu Quang 楚狂, literally “a lunatic from the Chu State,” a talented scholar and a contemporary of Confucius in the fifth century BCE who refused to put his talent in service for any power contenders during the chaotic Spring and Autumn era. The record of his encounter with Confucius appears in The Analects.

b Phan Tây Hồ is Phan Chu Trinh's penname.

c “Hiệp hồng nữ sĩ,” literally “the Lady, with Knight Soul,” is a penname. I have not been able to locate the identity of this author, but it is most likely that it was a male writer who read Literary Sinitic and who witnessed the Duy Tân Movement.

d José Rizal (1861–96) is the national father of the Philippines. The narrator claimed that he had a granddaughter who was raised by a Japanese rōnin 浪人 (a samurai with no master or lord) and was thus versed in Literary Sinitic and was able to have brush talks with the narrator. Brush talk (筆談; “bi tan” in Chinese; “bút đàm” in Vietnamese) is used by two individuals who have no common spoken language but can communicate by writing in Literary Sinitic.

e The plot might have been partially influenced by Herman Melville's classic Moby-Dick.

For Nguyễn Bá Trác, Siam, Hong Kong, Japan, and China constituted the Rivers-and-Lakes World, with Japan and China representing the new and old spaces of văn minh, respectively. The two spaces aroused different emotions in him. His feelings for Japan were overwhelmingly positive: he found Japan to be clean, modern, prosperous, and well-organized, and Japanese people to be civilized, polite, hardworking, and patriotic (Nguyễn Bá Trác Reference Trác1919, Nam Phong 25:13–17; 1919, Nam Phong 26:44–52; 1919, Nam Phong 27:81–93). His feelings for China, however, were far more complex. As a member of the last generation of Confucian scholars in Vietnam, Nguyễn Bá Trác had already established an understanding and perception about China well before he arrived there. Once there, he found some practices revolting and some of its big cities busy, yet morally decadent. But he also felt nostalgic when he visited some famous tourist attractions that appeared frequently in Chinese Tang poems and that drew many Southern envoys en route to the Middle Kingdom, especially those located in the Jiangnan area (Nguyễn Bá Trác Reference Trác1919, Nam Phong 29:151–53), which was geographically and historically tied to the Red River Delta, the traditional heartland of Vietnam.Footnote 4

Nguyễn Bá Trác employed two mechanisms to move his adventures forward. The first, similar to the sworn communities who help the protagonist navigate the Rivers-and-Lakes World, involves kind-hearted people who provide vital connections and financial support. These characters emerge at every critical moment of transition and enable the author to continue his adventure. Nguyễn Bá Trác communicates with many of them via brush talk in Chinese characters. Representing a variety of nationalities and encountered in a range of contexts, these figures—from a Vietnamese steamboat owner who takes Nguyễn Bá Trác from Saigon to Siam for free, to a Chinese male who pays his living expenses and tuition for his study in Japan, to a Japanese police chief who advises him to leave Japan and covers all his costs for sightseeing in Japan—are all anonymous and volunteer to assist Nguyễn Bá Trác without being asked. In the case of the Chinese man described above, he offers to assist Nguyễn Bá Trác after first being fascinated by the Chinese-translated Western adventure novel the latter is reading on his way to Japan in a liner. Here, it is likely that Nguyễn Bá Trác was alluding to Liang Qichao's experiences; he was given The wonderful encounters with the beauties by a Japanese captain as he escaped to Japan after the failed Hundred-Day Reformation. While in China, a kind Chinese officer enrolls Nguyễn Bá Trác in a military school and pays all his tuition and living expense. In the middle of his training, a Vietnamese senior lady approaches him, and Nguyễn Bá Trác gets to know her daughter, a young, talented, beautiful, and patriotic girl with a Vietnamese mother and a Chinese father. Determined to stay Vietnamese, she admires Nguyễn Bá Trác's talent and tries to have him marry her so that she and her Vietnamese mother can return to Vietnam with him. Nonetheless, Nguyễn Bá Trác does not reciprocate her feelings, because he feels he is not ready to settle down and get married. He is heartbroken when he later learns that the girl is killed by a wealthy and powerful scoundrel in revenge for her refusal to be one of his concubines.

The second narrative mechanism involves the descriptions of danger. Nguyễn Bá Trác includes four such episodes in his accounts, which send him from Japan to China, from place to place in China, and finally from China back home on the eve of World War I. Of these four episodes, the most fascinating one takes place in Japan. When he arrives in Tokyo, thanks to the advice and assistance of a kind-hearted Chinese man who came to him to borrow the adventure novel, Nguyễn Bá Trác tries to hide his nationality by passing as a Chinese surnamed 高 (Gao in Chinese, Cao in Vietnamese, and Ko in Korean). Unfortunately, shortly before his arrival, Itō Bumi 伊藤博文, the governor-general of Korea, which was at that time a protectorate of Japan, is assassinated by a Korean patriot. Through a series of mishaps, Nguyễn Bá Trác finds himself being followed by a team of Japanese agents, who first mistake him for a Korean and then a Chinese revolutionary due to his false surname.Footnote 5 He explains that he is able to make sense of what is happening to him because he has read of similar situations in other adventure tales and some detective novels. When he manages to meet the chief of police in Tokyo, he complains that he has not been treated in a very văn minh manner. The chief apologizes and offers to cover all the costs incurred from sightseeing. Through this narrative, Nguyễn Bá Trác affirms Japan's văn minh and beauty before he heads for China (Nguyễn Bá Trác Reference Trác1919, Nam Phong 24:217–21). After a short but romantic encounter with the Vietnamese admirer, Nguyễn Bá Trác moves on with his journey in the Rivers-and-Lakes World and witnesses the overthrow of the Qing dynasty by the Republican Revolution in 1911 while in Hong Kong. He decides to call it a day and returns to Vietnam on the eve of World War I, after he narrowly escapes stray bullets in a crossfire between revolutionaries and counter-revolutionaries.

These narrative devices illustrate the uniqueness of colonial Vietnamese reformed scholars’ rivers-and-lakes adventure stories between the 1910s and 1920s. Both the theme of danger and the tendency for the protagonists to be relatively passive and absolutely indebted to others who move the action forward were handled in ways that differentiated Vietnamese adventure tales from their Western and Chinese counterparts. First, danger was an essential literary component in Western, Vietnamese, and Chinese adventure tales alike, but Vietnamese heroes differed from their Western and Chinese peers in significant ways. In Western adventure tales, the protagonist leaves civilization to explore untamed areas overseas. His masculinity grows as he overcomes trials along the way and brings civilization in his wake. The danger is typically described in great detail and drama. In Vietnamese adventure tales, by contrast, physical danger is mentioned only briefly, and only then as a device to get the story going. As the journey progresses, the protagonist's level of văn minh grows, though not through the sort of heroic events featured in Western narratives.

Second, far from being hypermasculinized, the protagonists in Vietnamese adventure tales resemble the soft, fragile scholar/student archetype popularly found in the Chinese genre of scholar-beauty romance fictions (Song Reference Song2004)—one of the traditional Chinese literary pairings most popular in precolonial Vietnam. Whereas the Western hero survives thanks to his own resilience, the Vietnamese protagonist benefits from the assistance of kind-hearted people and rarely suffers along the way. In addition, while the Chinese hero in the Rivers-and-Lakes World would go a long way to repay his sworn brothers’ kindness, even to the extent of sacrificing his own life, his Vietnamese counterparts do not seem to feel obliged to do the same. I suggest that this passivity on the part of many of these Vietnamese protagonists likely reflected the authors’ sense of powerlessness and inadequacy derived from their experiences with the Duy Tân Reform Movement and their sense of ambivalence about the discourse of Enlightened Civilization and its practices and its contradictions in colonial reality.

Another notable feature of Nguyễn Bá Trác's story is the way it includes a variety of characters involved in East Asian anti-colonial revolutionary activities. The technique, also seen in other such adventure tales, helped to enhance the readability of the story and enabled the author to include discussion of various historical events and political issues. In one instance, for example, Nguyễn Bá Trác created an anonymous Korean patriot exiled in China. Claiming he developed a special bond with this Korean exile, he uses the opportunity to insert an account of the history of Korea's loss of national sovereignty (Nguyễn Bá Trác Reference Trác1919, Nam Phong 29:153–59).

The reference to Korea was hardly surprising. Since Japan managed to rise from a peripheral society in the Sinographic cosmopolis to Asia's most significant power after the Meiji Renovation in 1868, astounded intellectuals in China, Korea, and Vietnam had clamored to identify what it was that enabled this unprecedented reshuffling of power. Colonial Vietnamese intellectuals, who had in the past focused only on China, now developed a new interest in Korea. Discourses of how the enduring presence of the imperial examination in Korea, Vietnam, and China and its notable absence in Japan paved different paths for each society had been predominant in Vietnam since the Duy Tân Movement. For a Duy Tân scholar like Nguyễn Bá Trác, discussing the colonization of Korea and adding characters such as Korean revolutionaries in his story was a way of using the rivers-and-lakes trope to create a transnational Asian fraternal space of revolution. In such a space, the author could then freely express his identification with the anti-colonial struggles in Korea (and by implications, other Asian societies), a society that shared a similar past and predicament of colonization as that of Vietnam in the early twentieth century.

Dreaming the Peach Blossom Văn Minh in the Rivers-and-Lakes World: Tản Đà’s Small Daydreams

Small daydreams is a dreamy account of Tản Đà’s imaginary travels around the world and his accidental discovery of the ideal Peach Blossom văn minh. Tản Đà is the penname of Nguyễn Khắc Hiếu (1889–1939), a famous but bitter poet who never managed to pass the imperial examination despite his prodigious literary talent. When young poets formed the Self-Strengthening Literary Group in 1932, Tản Đà became the target of their iconoclastic attacks. In Small daydreams, over the course of his journey, Tản Đà’s adventures take place in four spaces that symbolize văn minh in various ways; these are, in order of appearance: a gold store owned by a successful French businessman in Saint Étienne, France; a brothel called the “City of Sorrow” (Sầu Thành) in New York; another store in Washington, D.C.; and a Peach Blossom nowhereland near the Arctic Circle. Like Nguyễn Bá Trác, Tản Đà enjoys both the assistance of kind-hearted people and admiration from beautiful and talented Vietnamese girls.Footnote 6

The gold store, the first văn minh space in the account, is Tản Đà’s base in the Rivers-and-Lakes World. He gets a job in the store thanks to his friend, a French official in Cochinchina who knows the store owner. Tản Đà’s first impression of the store as a “golden world” (Tản Đà [1917] Reference Đà and Xương2002, 73) establishes it as a site symbolizing the “light of enlightenment,” an idea popular among French imperialists. Things go smoothly at first: the owner takes a special liking to Tản Đà and pays for English and French lessons to “civilize” and prepare him for his future adventures. Tản Đà also meets an admirer, a beautiful and talented young maiden, Chu Kiều Oanh, who is knowledgeable in Western learning but also passionate about the future for Vietnamese national literature. The couple flirts and discuss Tản Đà’s writings, sharing their concerns regarding Vietnam's future (75). Learned men in colonial Vietnam considered discussions of literature in particular to be intellectual and patriotic and therefore suitable for the modern archetype of the scholar-beauty couple, who were frequently portrayed as leading the country into the future while enjoying romantic Platonic love.Footnote 7 Chu Kiều Oanh, a Vietnamese girl born in France, symbolizes the author Tản Đà’s belief that the best văn minh would happen if the Vietnamese could exercise their agency and selectively combine the best components of Enlightened Civilization and Vietnamese culture together.

Tản Đà stumbles upon the second space of văn minh—a brothel—while exiled in America. The exile results unexpectedly when the gold store is burglarized, and Tản Đà panics, thinking his boss will suspect him. True to type, Tản Đà remains passive, and it falls to Chu Kiều Oanh and another female friend to help him stow away in a coffin and put him on a steamer to New York. Once there, he is able to get by with the English skills he learned in France and the allowance given to him by the two girls, but he is unable to find a job and soon grows bored. One day, he wanders off the beaten path and finds himself in a place full of women. Far from beautiful, young immortals, however, these are American prostitutes, most of whom are well past their prime. He spends the remainder of his money on the women in the City of Sorrow—not courting them, but paying them to sing songs and play the pipa for him, while he writes them poems in return.

Financially questionable, Tản Đà’s decision to spend his money in this way serves as a means for the author Tản Đà to demonstrate his own sophistication. From the seventeenth century onward, an intellectual subculture began to emerge in Southern China's affluent urban areas, in which it was a sign of distinction to use poetry to woo knowledgeable and beautiful courtesans. Indeed, the popularity of a courtesan was believed to be reflected in the taste, talent, and characters of her suitors (Yeh Reference Yeh2006). In precolonial Vietnam, there were similar anecdotes of affairs between scholars and ả đào, songstresses who performed chamber music to entertain royal courts, scholars, and bureaucrats (Nguyễn Ngọc Thành and Hà Ngọc Hòa Reference Thành and Hòa2012).Footnote 8 Having the character Tản Đà visit a brothel was thus the author's own way of claiming a level of văn minh and showing off his literary talent in composing poems, a talent once highly valued among precolonial Vietnamese scholars and exam takers, but increasingly undervalued under French rule. Tản Đà concludes his visit by pitying his ignorant Vietnamese friends who spend their entire lives in the darkness of his hometown (Tản Đà [1917] Reference Đà and Xương2002, 87), while asserting that visiting such a brothel is considered “very văn minh” by Americans (85).

Tản Đà enters a third văn minh space, this time by traveling first to Washington, D.C., where he works at a store owned by a recently deceased friend of Chu Kiều Oanh's father. Tản Đà performs his job so well that he finds favor in the eyes of the owner of the new store, and he feels he is a “tycoon in a land of văn minh” (93). The protagonist Tản Đà’s success, I argue, reveals the author Tản Đà’s desire to win recognition and respect from the inhabitants of a văn minh land—specifically, America. He improves his English, learns other foreign languages, and “climbs up the social ladder” by befriending other intellectuals, with whom he discusses Vietnam's lack of văn minh in social customs and learning.

Invited to travel around the world with a retired doctor, Tản Đà joins a cruise that delivers him into the fourth space of văn minh when the ferry is hit by thick sea ice after sailing away from Niagara Falls. Seven passengers are killed, and the remaining survivors abandon the ferry and discover an island paradise inhabited by the most civilized races in the world. The survivals’ arrival in this icy version of Peach Blossom utopia marks the story's climax—not only Tản Đà’s arrival at a sublime space of ideal Enlightened Civilization, but also, symbolically, the achievement of văn minh for an entire generation of the Duy Tân scholars.

Here, the author Tản Đà combines Confucianism—especially the idea of Great Unity (大同; “datong” in Chinese), or a state in which perfect peace and harmony reign because people do not pursue their self-interest—with Western scientific novels and socialist utopian ideas to create the perfect văn minh space. As usual, it takes accidents and disasters to disrupt the protagonist's journeys in the Rivers-and-Lakes World and transport him to the Peach Blossom Spring utopia, where the ideal of văn minh is embodied in the inhabitants’ deeds, characters, technology, and societal arrangements. All the usual characteristics of the Peach Blossom Spring are here: beautiful scenes of nature, plentiful resources, and tranquil social relations. But so too are other markers of human advancement, including an intricate crystal palace,Footnote 9 as well as technological marvels that draw warmth from the earth and moonlight, an idea possibly inspired by French novelist Jules Verne's Journey to the Center of the Earth ([1864] 2008). The elder inhabitants of this space—attractive, elegant white people whose language sounds like English—welcome the survivors and explain that their ancestors left the “Old World” of England in anger and frustration in 1770 (101). Here, the author Tản Đà inserts an allusion to the iconic Mayflower voyage from England to the New World America in the seventeenth century. In this way, he further constructs a contrast between the colonial reality in which he was living and the ideal of văn minh about which he dreamed.

In a particularly innovative move, the author Tản Đà also draws upon the racial dynamics of America both to offer a subtle critique of Franco-Vietnamese relations and to situate Vietnamese văn minh as at least more developed than that of another Other. While all the Mayflower pioneers were white people, the inhabitants of the Arctic New World consist of both white people and “redskins” (người da đỏ), with a ratio of one to two. “Redskins” is, of course, a disparaging racial term used by European colonizers to describe North American indigenous peoples, but for the author Tản Đà, a scholar imbued with the Social Darwinist idea that indigenous peoples were the most inferior and backward races, the term functions in a way that is simultaneously condescending and hopeful. At first, the character Tản Đà does not even notice the existence of the redskins; only when the elders point them out does he realize how marvelous this new New World is: the white people are so fully committed to perfecting evolution and improving their chances of survival in the Arctic Circle that they allow not the slightest waste of time and energy on wars and conflicts. Consequently, even the redskins are able to make good progress in becoming văn minh and gaining the right to vote (113). The implication is that if even the lowliest race in the world could become văn minh under the care of the white people, so could the Vietnamese, who supposedly occupied a much higher position in the racial hierarchy and were currently under the protection of France, the birthplace of văn minh. In the author/protagonist Tản Đà’s words of amazement: “[L]ook at their intelligent look and their dignified conduct, who can tell that they come from the same racial stock of the native peoples in North America!” (113).

This văn minh space is wealthy and peaceful without the presence of currency or a market economy. While Tản Đà is amazed, his Western travel companions are embarrassed and defensive. They assert that thanks to human competition they, too, have made great strides in evolution, but they are only further shamed when they are reminded that evolution in the old New World has produced both positive and negative outcomes. For instance, as laws have evolved, so too have criminal activities, and the benefits of the positive aspects of competition have thus been canceled out by the harm associated with the negative aspects (111–12). These comments about the old New World echo the common perceptions about French Enlightened Civilization held by colonial Vietnamese reformed scholars: it was materially fascinating and productive, but morally dangerous and decadent.

Creating a Vietnamese Văn Minh Space: Nguyễn Trọng Thuật's Watermelon

Watermelon, clearly influenced by Robinson Crusoe, is a fictionalization of a short folktale “The tale of watermelon” (Tây qua truyện 西瓜傳; literally “melon from West”) that first appeared in Lĩnh Nam chí ch quái 嶺南摭怪 (Arrayed tales of selected oddities from the south of the passes) in the fifteenth century.Footnote 10 The protagonist of the original story is a non-Vietnamese young man who arrives in Vietnam as a boy via maritime trading ships during the time of the Hùng kings (Hùng Vương), the legendary progenitor of the ancient Văn Lang 文郎 kingdom who allegedly ruled the Red River Delta in 4000 BCE before it was turned into the southernmost province of Chinese empire in the second century BCE.

According to the original version, the Hùng king selects the boy to be his servant, names him An Tiêm 安暹, and looks upon him with favor as the boy grows. But An Tiêm becomes arrogant and claims that his wealth and honor are derived from accomplishments in his previous life. The king is enraged and exiles An Tiêm and his family to a sandbank in the sea. An Tiêm's wife is distressed, but An Tiêm is perfectly happy. He assures his wife that since Heaven gave birth to him, the very same Heaven will surely provide for him. Just then a giant white bird emerges with seeds that soon grow into fruits. Because the fruit is tasty and grows in abundant quantity, An Tiêm and his family not only survive but also become wealthy by selling the fruit to traders, farmers, fishers, and villagers. When the king is told that An Tiêm and his family are prospering thanks to the unknown fruit, he has to admit that An Tiêm is indeed fortunate, and not just thanks to the king's favor. The story ends with the king asking An Tiêm back and reinstituting him in the royal court (Chen and Sun Reference Qinghao and Xun2010).

The story, with its elements of exile, isolation, and successful trading activities, presented an excellent opportunity for the author Nguyễn Trọng Thuật to imaginatively return to Vietnam's past and set it upon the path to văn minh. Nguyễn Trọng Thuật worked as an editor for the influential colonial journal Nam Phong, and subscribed to a specific form of humanistic Buddhism (renjian fuojiao/phật giáo nhân gian 人間佛教) that originated in China in the early twentieth century and emphasized service for the living, rather than rituals for the dead. Ancient Vietnam, in Nguyễn Trọng Thuật's story, can become a perfect văn minh space if Confucianism, nationalism, and science exist in harmony under the leadership of a Vietnamese Robinson Crusoe who is also a Confucian sage-king. The story resonated with resurgent interests in the mysterious Văn Lang kingdoms and the Hùng rulers in colonial Vietnam (Nguyễn Thị Điểu Reference Điểu2013).

In the preface, Nguyễn Trọng Thuật explained why he was moved by Lĩnh Nam chích quái: he discovered in these stories strong evidence that prior to the long period of Chinese reign, Vietnam had its own civilization that was totally different from that of China and bore some resemblance to other world civilizations. Of all the surviving stories, Nguyễn Trọng Thuật found Watermelon particularly appealing because he saw in the protagonist An Tiêm a perfect combination of both the modern spirit of adventure and the deep wisdom of the mystery and philosophy of Heaven. Explaining his motive in fictionalizing Watermelon, Nguyễn Trọng Thuật insisted that the story was no less than a historical document about a real adventurer, whom he believed was also a nationalist, a prophet, a Confucian sage-scholar, and a benevolent and wise colonial master (Nguyễn Trọng Thuật Reference Thuật1926, Nam Phong 103:69).

Of course, Nguyễn Trọng Thuật had to reconcile the original An Tiêm's arrogance, and he argued that An Tiêm was the first Vietnamese who embraced both Confucianism and Buddhism, with the former emphasizing loyalty and the latter the power of karma. Because these two schools of thoughts were newly transmitted to Vietnam during the era of the Hùng kings, people mistook An Tiêm's acknowledgement of the role karma played in his life for ingratitude and thus were offended. Nguyễn Trọng Thuật explained that he wanted the reader to recognize that the home pagoda was no less effective than the foreign ones and thus people should look no further than their hometown buddhas and deities for help (Nguyễn Trọng Thuật Reference Thuật1926, Nam Phong 103:169).

Nguyễn Trọng Thuật set the backdrop of the story in a time when the inhabitants of the Văn Lang kingdom were struggling with a “barbarous” Thục people (rợ Thục). Though Nguyễn Trọng Thuật did not specify, he put his hero in the Warring States period (475–221 BCE), from which the centralizing Chinese Empire as we know it today emerged. According to Chinese and Vietnamese records, the Shu/Thục 蜀 kingdom was located in today's Sichuan 四川 Province, and in 275 BCE, a prince of Shu/Thục named An Yang Wang/An Dương Vương 安陽王 invaded Văn Lang and put an end to the genealogy of the Hùng kings. In 221 BCE, the Qin state annihilated its rival states—including Shu/Thục, and that is how the Red River Delta became part of China's territory for the next millennium (Holcombe Reference Holcombe2001).

The beginning of the story is a nod to Vietnam's history of Nam Tiến, that is, southward advance that resulted in present-day Vietnam's S-shaped territory at the expense of the ancient Champa kingdom and neighboring Cambodia. During the colonial period, Vietnamese intellectuals began to use Nam Tiến to create a glorious past for Vietnam (Ang Reference Ang2013), and Nguyễn Trọng Thuật was no exception. This interest was preceded by Liang Qichao, whose essay “On China's eight great colonizers” proudly listed some overseas Chinese historical figures who rose above their humble origins and turned themselves into kings and rulers in Southeast Asia, and appeared in his Collected essays from the ice-drinker's studio. Worrying about the threats from the Thục people, An Tiêm proposes that the king should send people out to explore and acquire new territory so as to increase the kingdom's wealth and power. The king is pleased with this idea, and An Tiêm's team is the most successful of all the expedition teams. But his success leads to his own banishment to the Rivers-and-Lakes World. Officials who fall out of the king's favor become resentful and spread rumors that An Tiêm denies the favor the king bestows upon him and attributes his success to his own karma instead. They further suggest that the king exile An Tiêm to the island in the sea in order both to giáo hóa (civilize) the barbarians there and to see whether he can, indeed, develop the island without any assistance from the king, thus testing his karma (Nguyễn Trọng Thuật Reference Thuật1926, Nam Phong 103:173).

Giáo hóa, or jiaohua in Chinese, as I pointed out earlier, was the Sinitic version of Enlightened Civilization and the organizing principle of the Sinographic cosmopolis, in which the Middle Kingdom believed itself to be the sole source of universal truth, learning, and wisdom to which other barbarian societies should pay tribute. The principle of giáo hóa designated that the closer to the center a barbarian was, the more blessings of jiaohua he would receive. After Vietnam broke away from Chinese rule in the tenth century, it became a vassal kingdom of China until the late nineteenth century. Over time, Vietnam absorbed the idea of jiaohua and tried to establish its own Vietnam-centric giáo hóa world in Southeast Asia by demanding tributes from its neighbors such as Champa and Cambodia, with mixed results. In the story, the island is located far away from Văn Lang, and thus symbolizes a barbarous space awaiting giáo hóa from a civilized Văn Lang.

When An Tiêm and his family are exiled by the dysfunctional Confucian state to the Rivers-and-Lakes World, his task is two-fold: he must redeem his reputation by bringing the barbarous island under state control through the Vietnamese version of mission civilisatrice, and he must restore the state to the ideal Confucian order. As in the two adventure stories discussed above, Nguyễn Trọng Thuật spends little time describing the dangers and difficulties An Tiêm encounters. An Tiêm and his wife believe that, as long as one has honesty, perseverance, reverence for Heaven and one's king, as well as love for one's nation and people, God—whom An Tiêm also refers to as Creator or Heaven—will help one overcome whatever hardship and difficulties may come (Nguyễn Trọng Thuật Reference Thuật1926, Nam Phong 103:177–78).

The process of civilizing the island involves five stages, after each of which An Tiêm worships God by offering tears of gratitude, dancing, and singing—the latter two of which were considered by Confucius to be essential components of successful jiaohua/giáo hóa—and finally, the watermelon he grows. The first stage involves a fire so as to enter the phase of Toại nhân, or Suiren 燧人 in Chinese (Nguyễn Trọng Thuật Reference Thuật1926, Nam Phong 104:288), one of the Chinese legendary progenitors who allegedly introduced the practice of drilling wood for fire in high antiquity. Next, An Tiêm finds the source of fresh water (Nguyễn Trọng Thuật Reference Thuật1926, Nam Phong 106:490). Once they have fire and fresh water, he starts the third phase by using a calendar and making proper clothes for them to wear, both when receiving guests and visiting a sacred hill from the top of which they could see their beloved Văn Lang (Nguyễn Trọng Thuật Reference Thuật1926, Nam Phong 107:94). In the fourth stage, he requires his children to learn to read and write, because “only through learning can one evolve” (Nguyễn Trọng Thuật Reference Thuật1926, Nam Phong 108:196). They learn the stories of their great Hùng kings written in “the characters of Chinese letter” (chữ Hoa văn) invented by Thương Hiệt, or Cangjie 倉頡 in Chinese, the mythical figure who is believed to invent Chinese characters, and “the characters of Vietnamese language” (chữ Việt ngữ) that the Hùng king created based on the Chinese characters (Nguyễn Trọng Thuật Reference Thuật1926, Nam Phong 108:197).

It is important to point out that, despite the existence of Nôm, many colonial Vietnamese intellectuals were troubled that their ancestors did not create Vietnam's “own” script, as was the case in Japan and Korea. Some insisted that it was impossible that a văn minh race like Vietnamese people failed to create their own script when their barbarous neighbors did, and they blamed China for the disappearance of their native script (Ng.-H-V 1918).

In the fifth stage, An Tiêm further establishes the Confucian social order. He bestows giáo hóa on two castaways from the Văn Lang kingdom, both of which can be seen as the Vietnamese equivalent to the character of Friday in Robinson Crusoe. After Crusoe saves an islander from cannibalism, he names him Friday, teaches him to speak English, encourages him to eat meat instead of human flesh, and converts him to Christianity. In Watermelon, An Tiêm saves two men from the seas and becomes their master. Realizing that they are ignorant commoners without any giáo hóa, he pities them and follows the good Confucian way of civilizing by teaching them to dress properly, sing songs, and worship God (Nguyễn Trọng Thuật Reference Thuật1926, Nam Phong 111:500).

The fifth stage is also the phase in which An Tiêm, with his giáo hóa accomplishments, wins respect and acknowledgement from China. In this stage, he cultivates agriculture, manages to light his home by using pine sap for fuel, and discovers watermelon under the guidance of a mysterious crow (Nguyễn Trọng Thuật Reference Thuật1926, Nam Phong 109:289). Traditionally, Vietnamese women dyed their teeth black for aesthetic reasons, and in the watermelon's red flesh and black seeds An Tiêm sees Vietnamese girls’ lovely lips and black teeth, so he names the watermelon “Việt Nga,” literally “beautiful Vietnamese lady” (Nguyễn Trọng Thuật Reference Thuật1926, Nam Phong 109:295). He chooses some of the best watermelon to offer to God and some others to send off to the sea, with his poems cut onto the watermelon skins. These watermelons with poems catch the attention of a junk from the state of Tề, or Qi 齊 in Chinese, one of the most powerful states during the Warring States period, which, in this story, serves to represent China. A famous scholar-mandarin on the junk admires the poems he reads on the watermelon skins, while the crew and the captain of the junk are impressed by the taste and medical benefits of the watermelon. They follow the clues in the poems to the island and begin brush talk with An Tiêm.

When the Tề people first spot the island, they see An Tiêm's two disciples and laugh at their shabby clothes. Therefore, when An Tiêm receives the Tề people, he makes a point to have his family and the disciples wear the proper “national costume” made by his wife. Soon, everyone from the Tề junk is so awestruck by An Tiêm that they view him as no less than a demi-god (Nguyễn Trọng Thuật Reference Thuật1926, Nam Phong 111:504). The captain strikes a trading deal with An Tiêm, and the scholar-mandarin enthusiastically recruits him to work for the Tề state, telling him “we here at China are in awe at your virtues” (Nguyễn Trọng Thuật Reference Thuật1927, Nam Phong 113:76). An Tiêm politely declines the offer, explaining that it is God who decides where people should live and flourish (Nguyễn Trọng Thuật Reference Thuật1926, Nam Phong 111:504). Through these diplomatic exchanges, the Tề people come to see An Tiêm's tiny island as the equal to China (Nguyễn Trọng Thuật 1927, Nam Phong 113:75). With China's recognition, the civilizing process is complete, and An Tiêm's adventures in the Rivers-and-Lakes World come to an idealized ending: thanks to his own perseverance and the grace of God, An Tiêm has successfully transformed a deserted island into a Confucian Peach Blossom utopia—in this case, a watermelon utopia—and won, for himself and his home country, the respect and admiration of its hegemonic neighbor.

Conclusion

Between the latter half of the nineteenth and the early twentieth centuries, a Western version of Enlightened Civilization entered East Asia and eventually displaced the preceding hegemony of Sinitic jiaohua. This transformation ushered in the dual projects of nationalism and modernization, which manifested through pan-East Asian Reform Movements aiming to achieve “civilization and enlightenment,” first in Japan in the late 1860s, then in China in 1898, and finally in French colonial Vietnam in the 1900s. This period also saw the collapse of the Sinographic cosmopolis, which had for millennia bonded East Asian political and cultural elites together through the knowledge of Literary Sinitic. As the dominance of Literary Sinitic drew to a close, the demand for linguistic and literary vernacularization began to emerge in Vietnam. For colonial Vietnamese reformed scholars, vernacularization was the first step toward the establishment of a national literature—something considered essential if Vietnam was to become a văn minh khai hóa nation deserving of sovereignty in the new international world of nation-states.

With relatively few literary materials at hand, the last generation of colonial Vietnamese Confucian scholars who were inspired by the pan-East Asian Reform Movements began to utilize their knowledge of Literary Sinitic to participate in the East Asian transculturation of Japanese literature. Their literary output constituted what I call a translated vernacular modernity—a literary vernacularization and emulation of Western literature first introduced into East Asia by Meiji Japanese thinkers and then made available to colonial Vietnamese intellectuals by Chinese translation and plagiarism of Japanese texts. Dignifying vernacular speech at the expense of a universal script was necessary for translated vernacular modernity: whereas in the precolonial era the vernacular Nôm script served as a pedagogical tool to facilitate the learning of Literary Sinitic, during the colonial period Literary Sinitic was demoted from the universal script and key to truth and wisdom in East Asia to one of many national scripts with which Vietnamese language was equal.

The genre of travel literature, including adventure tales and travelogues, was an appealing one to colonial Vietnamese intellectuals engaged in this translation of vernacular modernity. First, these scholars found that travel literature was relatively easy to imitate using the young quốc ngữ vernacular script, and they estimated that the growing quốc ngữ reading public who had long been familiar with Chinese historical novels and martial arts novels would be a receptive audience to the adventurous tropes of travel literature. Better yet, the literary realism of travel literature was perfect not only for cultivating the Vietnamese people's adventure spirit, but also for shifting their attention from remote China to their local society. Furthermore, travel literature provided colonial Vietnamese intellectuals a creative and flexible means to reflect on their own engagements with and opinions of Enlightened Civilization and Sinitic jiaohua/giáo hoá, something they had already begun in the Duy Tân Movement. Therefore, travel literature, including fictional and semi-fictional works, emerged after the Duy Tân Movement was suppressed in 1908 and before a young Westernized generation grew to replace the Confucian elites in the 1930s.

In this article, I have analyzed twelve travel stories by five Duy Tân authors, all of whom were well versed in Literary Sinitic. They were avid readers of Chinese literature and reformist writings, and through the latter they learned of the concept of Enlightened Civilization, which was what the French colonial government promised to bestow upon Vietnam. As they grappled with and selectively appropriated from this discourse, and reflected on its ascension over Sinitic jiaohua/giáo hoá, Vietnamese authors sought to create their own national literature. In doing so, they participated in what Karen Thornber (Reference Thornber2009) calls an intra-East Asian “literary contact nebula”—namely, Chinese, Taiwanese, Korean, and Manchurian processes of transcultural engagement with Japanese literature. Through their adventure stories, Vietnamese writers employed a strategy of literary spatialization that drew on the East Asian literary tropes of a dangerous, stateless Rivers-and-Lakes World leading, ultimately, to a blissful Peach Blossom Spring văn minh utopia. By imagining adventures that took place in strange wonderlands beyond the constraints of their daily lives, these authors were able to both escape and critique the colonial reality, while envisioning a specifically Vietnamese version of civilization or văn minh.

The twelve stories can be categorized into three groups. The first group includes eight stories that features the protagonists’ voyages in the Rivers-and-Lakes World, of which Nguyễn Bá Trác's An idyllic wanderer's travels is the best known. The three stories in the next group highlight sublime experiences in the Peach Blossom Spring utopia; Tản Đà’s Small daydreams is the most popular example here. The protagonists of both An idyllic wanderer's travels and Small daydreams are the authors themselves, depicted as passive scholars who only prevail thanks to the assistance of kind-hearted foreigners and beautiful and patriotic Vietnamese girls. These two works were influenced by famous Chinese reformists’ nonfictional travelogues, whose purpose was to introduce different cultures and peoples to their Chinese readers. Both works, like the Chinese travelogues that inspired them, include commentary on various societies’ history and culture, especially those that shared the similar fate of colonization with Vietnam. But unlike their Chinese counterparts, the Vietnamese stories wove together fictional and nonfictional elements. Finally, in the third category, we find Nguyễn Trọng Thuật, who rewrote a very short and relatively obscure folktale Watermelon into a Vietnamese version of Robinson Crusoe. Whereas the other stories I discuss told of protagonists accidently discovering a Peach Blossom Spring văn minh space via the Rivers-and-Lakes World, Nguyễn Trọng Thuật had a more ambitious aim. Watermelon thus tells of a Confucian sage and adventurous hero from Văn Lang who transforms a deserted island into a văn minh land so civilized that it wins admiration from the Chinese themselves.

The study of these colonial Vietnamese travel stories in the 1910s and 1920s makes two contributions to the field of Asian studies. First, the stories can be seen as the fruits of colonial Vietnamese intellectuals’ efforts to create a national literature by translating Chinese texts that were themselves transculturations of Japanese literature. The stories were meant to both perform and reflect modernization; as such, they demonstrated colonial Vietnamese intellectuals’ engagement with translating vernacular modernity. Their literary output not only testifies to the diverse paths to modernity they imagined, but also demonstrates the mediating role played by Literary Sinitic within and along those paths, even as the Sinographic cosmopolis was disintegrating in the latter half of the nineteenth century. Second, while scholars have the various temporal, racial, and gendered assumptions of civilizational discourse that imagined colonial projects as masculinist adventures, this article explores the spatial dimension of Enlightened Civilization and pays attention to the imagined adventures and travels of colonized subjects themselves.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Asia Research Institute at the National University of Singapore, the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies in Singapore, and the Center for Asia-Pacific Area Studies at Academia Sinica in Taiwan. Exchanges with Phựng Minh Hiê´u and comments from Prasenjit Duara, Yi Li, Nguyễn Phúc Anh, Bruce Lockhart, and especially two anonymous reviewers greatly improved the quality of this manuscript.