Introduction

Pedagogy as a social relationship is very close in. It gets right in there – in your brain, your body, your heart, in your sense of self, of the world, of others, and of possibilities and impossibilities in all those realms

I argue these effects can be accomplished through professional work in services for families with young children, if they unfold through effective partnerships between parents and professionals. This chapter is based on a premise that in such partnerships, the pedagogic nature of professional work is intensified (Fowler & Lee, Reference Fowler and Lee2007; Fowler et al., Reference Fowler, Rossiter, Bigsby, Hopwood, Lee and Dunston2012; Hopwood, Reference Hopwood2014b, Reference Hopwood2014c, Reference Hopwood, Green and Hopwood2015a, Reference Hopwood2015b, Reference Hopwood2016; Hopwood et al., Reference 42Hopwood, Fowler, Lee, Rossiter and Bigsby2013b; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Dunston, Fowler, Hager, Lee and Reich2012; Rossiter et al., Reference Rossiter, Fowler, Hopwood, Lee and Dunston2011). This is not a pedagogy inducting parents into expert communities. It is based on reciprocal learning, where what is learned cannot be specified at the outset, and where the expertise of both professionals and parents is brought to bear.

I begin by outlining how cultural historical activity theory (CHAT) enables us to refresh views of professional expertise and challenges in professional work. I then introduce the Family Partnership Model (FPM) (Davis & Day, Reference Davis and Day2010). I frame it as a particular instance of co-configured practices, theorising it in CHAT terms. Relational agency has been shown to be a crucial feature of working with families. However, as Edwards and Kinti (Reference Edwards, Kinti, Daniels, Edwards, Engeström, Gallagher and Ludvigsen2010) note, the Learning in and for Inter-agency Working (LIW) study (Edwards et al., Reference Edwards, Daniels, Gallagher, Leadbetter and Warmington2009) found parents often in marginal position, as practitioners needed to become comfortable with interprofessional negotiations before they could negotiate their expertise with parents. I pick up on this crucial, but as yet underexplored, issue, drawing on a study of a residential parenting service run by Karitane, where the idea of partnership between professionals and parents has taken hold in the form of the FPM.

Research Problem: Building Resilience in Parents with Young Children

Karitane is based in Sydney and works with parents and their children from birth to four, offering parenting support and advice, antenatal support and education and services to alleviate parental depression and anxiety. These services are funded by the New South Wales (NSW) Ministry of Health and the Department of Family and Community Services. All of Karitane’s services operate on principles of identifying risk, intervening early and building resilience. Risk factors are considered in relation to the child, mother, partner, family parent–infant relationship, environment and life events. They are categorized as one of three levels: 1 – no specific vulnerabilities detected; 2 – factors that may impact the ability of the parent to respond, including an unsupported parent, infant care concerns, multiple birth, housing, depression and anxiety; and 3 – complex risk factors, including mental illness, drug and alcohol misuse, domestic violence and current/history of child protection issues. The Residential Unit where the study was based accepts families in the latter two categories.

I conducted an ethnographic study in the Unit (Clerke & Hopwood, Reference Clerke and Hopwood2014; Hopwood Reference Hopwood and Denzin2013, Reference Hopwood, McLean, Stafford and Weeks2014a–Reference Hopwoode, Reference Hopwood, Green and Hopwood2015a, Reference Hopwoodb, Reference Hopwood2016; Hopwood & Clerke, Reference Hopwood and Clerke2012). It accepts around ten families each week, experiencing significant challenges with children under four. Families arrive on Monday and leave on Friday. While there, they receive support from child and family health nurses, a paediatrician, psychiatrist, social workers, child-care assistants and administrative staff. The nursing team operates over twenty-four hours, through three shifts, and each family has at least one nurse assigned to them for each shift. Families are referred by their doctor or local child and family health nurse, for help with challenges of sleep and settling, night waking, breastfeeding, solid food intake and toddler behaviour management (Hopwood & Clerke, Reference Hopwood and Clerke2012). These are known to constitute risk factors, which have detrimental impact on family mental and physical well-being. Karitane’s success is conveyed in the following extracts from letters from mothers, after their stay:

Karitane helped to change our family life significantly. I was suffering with postnatal depression brought on by sleep deprivation as my little girl was a very bad, unsettled sleeper. This impacted terribly on my relationships with Jayne, my partner and my ability to cope on a day to day basis.

Before my week at Karitane I was so incredibly down, flat, emotional, anxious, nervous, exhausted … the list goes on. I didn’t know myself or how to be myself anymore. I felt like I was under a heavy grey cloud and everything around me had turned from vibrant beautiful colours to black and white. I so desperately wanted to not feel this way, but I had no strength or energy to change things. … I, like many mothers, had lost so much confidence from my lack of sleep. I felt like I was failing every step of the way. Failing my baby because I could not get him to sleep on his own, failing my partner because I had no time or energy for him, and failing myself because I just didn’t know who I was any more.

Over five days, it is impossible to fully address issues such as an infant’s frequent night waking. The Unit thus aims to challenge parents’ constructs of themselves as failing or of their children as pathological and to equip them with strategies that they can implement at home. It also refers parents to other services and support within their communities.

My focus on this service continues a thread in much of the research through which the concepts of common knowledge, relational expertise and relational agency have been developed. It is about future-oriented, state-led interventions that seek to disrupt trajectories that (re)produce disadvantage and exclusion by building resilience in families at risk. Edwards and Mackenzie (Reference Edwards and Mackenzie2005) view resilience as repositioning selves as agentic participants through development of protective factors, such as positive self-regard, reflection, consistent and warm family relationships and appropriate support through extended family and the community. In CHAT terms, this can be expressed as expansive learning (Engeström, Reference Engeström1999), repositioning oneself in relation to one’s world and acting (differently) to transform it, as a result of changed interpretations of that world (Edwards & Mackenzie, Reference Edwards and Mackenzie2005).

This links to Edwards’ Charles Taylor–informed idea of agency, which involves being able to set goals, adjust them in light of experience and evaluate progress towards them. In FPM, services do not seek to solve problems for families, but help families develop the capacity to take control and negotiate their lives in ways that allow them to shape and benefit from what society has to offer. In the Unit, this involves helping parents take control over their parenting, developing the capacity to anticipate and respond to problems, shape their intrafamily relations and seek and benefit from external support when needed. Notably, some parents later become volunteers with the Unit or through community-based programs. The trajectories of such changes are not unidirectional, linear or uniform, but recursive (Edwards, Reference Edwards2007); both risk factors and protective factors that are emplaced are dynamic, existing in shifting relationships with one another.

A Refreshed View of Professional Practices and Expertise

What Edwards (Reference Edwards2010, Reference Edwards2011) refers to as the relational turn in expertise reflects a stance in contemporary professional practices. Central to this is a reshaping of relationships – whether between different professions or between professions and service users. The policy framing of this refers variously to interprofessional practice, interagency work, co-production and partnership (Dunston et al., Reference Dunston, Lee, Boud, Brodie and Chiarella2009; Fenwick, Reference Fenwick2012; Hopwood et al., Reference Hopwood, Dunston and Clerke2013a). The relationships implied here are diverse. For example, what service-user involvement might mean varies considerably – including contributing to service redesign, negotiations around priorities and more precise notions of partnership, such as those outlined in the FPM.

Edwards and Apostolov (Reference Edwards and Apostolov2007) use the term ‘co-configuration’ to describe the flexible working inherent in responsive collaboration in which no single actor has the sole responsibility and control. In describing child-centred practices for young people at risk, Edwards (Reference Edwards2007) notes how this requires agile responses to the uncertainty of developmental trajectories rather than delivery of planned arrangements. I argue, similarly, that in partnership practices (such as FPM), outcomes for families are not realized by implementing set interventions, but through complex, dynamic and always new knowledge work. There is no dilution of specialist expertise, nor hybridization, but a focus on how professionals draw on multiple forms of expertise to recognise and work with what matters for others (Edwards, Reference Edwards2011). Here, I focus on how professionals worked collectively to help parents struggling with their children. This collaboration involved recognising what matters to families and dealing with the complexities that arise when this knowledge is uncertain and unstable, and when the baton of relational work is passed from one professional to another.

Using the relational concepts to understand partnerships between professionals and parents places my analysis at a middle analytical level, between the system and the individual (Edwards, Reference Edwards2012). It views professional knowledge as accomplished in the ‘heat’ of practice, shaped by and responsive to new problems being worked on (Edwards & Kinti, Reference Edwards, Kinti, Daniels, Edwards, Engeström, Gallagher and Ludvigsen2010). Expertise is a capacity to learn, act on and transform problems of practice, including through work, that questions knowledge. Consequently, the object is never out of sight, and the issue is not knowledge in use, but the problem being worked on with knowledge in use (Edwards & Daniels, Reference Edwards and Daniels2012).

This refreshed view of being a professional, sustains the service ideal of making a difference (in this case to families) while emphasising a practice view of knowledge as a distributed resource, which is worked on and worked with in responding to complex problems (Edwards, Reference Edwards2010). This view of professional practice is not one of compliance with rules and deployment of ready-to-hand tools according to stable knowledge. Instead, it is one of questioning, reshaping and collective knowledge-making (Edwards & Daniels, Reference Edwards and Daniels2012).

The Family Partnership Model from a Chat Perspective

The FPM was developed by the UK Centre for Parent and Child Support (Davis & Day, Reference Davis and Day2010; Day et al., Reference Day, Ellis and Harris2015). Front-line staff complete a five-day foundation course that covers relational skills together with an explicit partnership framework (sharing decision making, recognising complementary expertise, maintaining unconditional positive regard for parents and practicing openness and honesty) and a stepwise helping process. It has been implemented in services in the United Kingdom, continental Europe and Australasia, including early parenting services, child and adolescent mental health services and speech and language development, and as the basis for school–parent relationships. It is explicitly named as the preferred model of care in NSW policy for maternal and child primary health services (NSW Health, 2009, 2011).

The FPM was developed in response to evidence on the ineffectiveness of child and family services based on an expert model where professionals appear to hold the relevant knowledge, dictate the terms and focus of work and lead the problem solving. Parents are much more likely to follow advice from others if they feel listened to, respected and actively involved in determining the agenda and trajectory of work with professionals (Davis & Fallowfield, Reference 40Davis and Fallowfield1991). FPM does not envisage hybrid roles or symmetrical relationships. It retains a clear need for specialist, professional expertise, particularly in guiding change (Day et al., Reference Day, Ellis and Harris2015). The outcome is not focussed on developing confidence, capacity and resilience in families, as well as connectedness with and contributions to support in the wider community. The adoption of an FPM partnership-based approach infuses the process with a strong pedagogic dimension, where the pedagogy is based on solutions that are not yet known and requires professional expertise and the family’s knowledge to interact.1

FPM outcomes, seen as helping parents take control over their worlds to reshape their lives, echo Edwards’ approach to resilience (Edwards & Apostolov, Reference Edwards and Apostolov2007). The focus is helping families change the conditions in which they develop. Attention to parents’ constructs and behaviours closely parallels notions of interpretation or meaning making and their relation to our actions on the world, which are key features of learning (Edwards, Reference Edwards2005a). The joint work in FPM means that together families learn how to interpret a problem and how to respond to it. This learning is embedded in the social practices of family life and in the social relations of partnership. FPM is not a rigid model but rather a basis for agile living practice, echoing Edwards’ (Reference Edwards2007) idea of responsive adaptive practice alongside service users.

Research on FPM has identified a challenge of implementation: professionals may move too far from the expert model, becoming focussed on empathetic and supportive relationships – what Fowler et al. (Reference Fowler, Rossiter, Bigsby, Hopwood, Lee and Dunston2012) term ‘being nice’. Professionals may resist challenge, seeing it as threatening the relationship, and explicit use of professional expertise, feeling it compromises partnership. FPM does not envisage a diluted form of professional expertise, but rather a different way of deploying it, seeing challenge as crucial to effecting change. It promotes a strong role for core professional expertise alongside an additional form of relational expertise, a ‘confident engagement with the knowledge that underpins one’s own specialist practice, as well as a capacity to recognise and respond to what others might offer in local systems of distributed expertise’ (Edwards, Reference Edwards2011, p. 34). Relational expertise finds expression in FPM in terms of helper qualities and skills, including respect; genuineness; empathy; humility; quiet enthusiasm; intellectual and emotional attunement; active listening; prompting, exploring and summarising; empathic responding; and the enabling of change in feelings, ideas and actions (Davis & Day, Reference Davis and Day2010).

The challenge of failing to go beyond ‘being nice’ parallels one of two forms of co-configuration described by Edwards and Apostolov (Reference Edwards and Apostolov2007). There they point to a difference between (i) an engagement with service users where the service is the problem space to be developed through evaluations and so forth and (ii) a form of engagement where the joint focus is the developmental trajectories of the children using the service. The former reflects the limitations of ‘being nice’, while the latter calls for attention to building the capacity of service users to take control over their own problems. The FPM is an example of the latter version. It is an explicitly goal-oriented model, advocating an approach where developmental trajectories are in focus.

Edwards conceives common knowledge as a mediator of relational agency (Chapter 1). It concerns shared understanding of the ‘why’ of practice, coming to know what matters. Through common knowledge, practice can be oriented towards coherent goals, and different actors can engage with different categories, values and motives. The FPM starting point is that professionals understand parents’ priorities, their struggles and the changes they want in their worlds. Then comes a phase of exploring constructs – how parents interpret the problems they are experiencing and the resources they can bring to bear. Here, common knowledge is often about revealing and exploring differences. For example, a mother’s ideas that she is a failure as a parent, and that her child does not love her, might not be shared by the professional, but their becoming explicit and a common basis for joint work is crucial. As Edwards (Reference Edwards2011) notes, what matters often becomes apparent through narratives of past, present and future. Early interactions between professionals and parents in the Unit take this form, through intake phone calls and admission interviews. However, as we will see, common knowledge is not simply established early to remain in place as a stable resource. It is a constant and dynamic dimension of the problem space of practice.

Finally, FPM can be understood as an approach to supporting families that requires and produces appropriate conditions for relational agency. This is a capacity for working with others to strengthen purposeful responses to complex problems (Edwards, Reference Edwards2005b, Reference Edwards2010, Reference Edwards2011, Reference Edwards2012). Professionals work with parents to expand the object of activity (Engeström, Reference Engeström1999), recognising what matters to the family and the resources they bring to bear in interpreting and responding to it. Professionals align their responses to new interpretations of the problem with parents’ responses and actions. The outcomes of FPM, conceived in this way, are not a reflection of core specialist expertise alone, nor the addition of relational expertise and the establishment of partnership with parents. Rather, mediated by common knowledge, parents and professionals work together to construct new interpretations of the problem and develop new responses to it. The professional is neither a leader or a passive observer in this process.2

The next section gives an account of work with one family, using data from handover and case conference meetings. These provide a window into relational work, the shifting and multidimensional problem space of practice, emerging solutions, and how they were arrived at. This is not an exhaustive account of the interactions between staff and the family. Pseudonyms are used and some factual details adjusted to ensure confidentiality.

Supporting Carly and Mark with Lizzie and Adam

Carly and Mark are parents of six-month-old Lizzie. They came to the Unit with Lizzie and two-year-old Adam. Mark is not Adam’s biological father, and Adam had been taken into foster care due to domestic violence between his biological father and Carly. Carly ended that relationship and began living with Mark, after which Adam returned to his mother. Carly and Mark wanted help developing a routine for Lizzie. Carly has a minor intellectual delay, and there is a query that Mark may have a similar condition or be dyslexic. Toddler Adam has been waking frequently at night and displaying challenging behaviours during the daytime.

On Monday night, a nurse was with Carly when she was bottle feeding Lizzie, and noticed that the liquid was very hot. The nurse suggested she check the temperature of the bottle, at which point Carly said, ‘I can’t do this at night.’ The nurses taking over the next morning planned to work with Carly on reducing the need for feeding Lizzie in order to resettle her during the night.

On Tuesday, Carly told a nurse that she wanted to encourage Mark to help make up feeding bottles and get more involved with settling both children. She felt she parented alone. The nurses and playroom coordinators noticed that Mark tended to focus on Lizzie, ignoring and withholding affection from Adam. Carly attended a toddler group, contributing by sharing her knowledge of toddler management strategies.

The nurse working with them overnight on Tuesday reported Mark’s aggressive behaviour: he became highly stressed and started to pinch Adam, pick him up and throw him down on the bed. The nurse felt Mark might punch Adam, and asked him three times to step outside for some time out. Eventually he walked out, saying, ‘I can’t do this.’ Later, they learnt from Carly that Mark has a history of hitting Adam on the head and that she is worried about Mark settling Adam, although she wants him to be involved in caring for him. Late on Tuesday, a nurse learns that Mark is not able to read or write.

On Wednesday morning, the team consider Carly’s goals, thinking about child safety, her well-being, Mark’s history and behaviours and the strengths they have observed, particularly Carly’s capacity to hold it together even during confrontational episodes at night. By this point, the work of detecting what the children respond to in terms of settling continues. Nurses and other staff are frequently seen at the nurses’ station writing in the medical records or on child behaviour charts that hang next to each nursery (Hopwood, Reference Hopwood2014c, Reference Hopwood2014d). Later that morning, the team became aware of Carly’s unease about what is being written about her. Given the history of this family with child protection services, the nurses acknowledged that Carly and Mark may feel particularly vulnerable to the idea of being judged. The decision was taken, and passed on to all professionals working with the family, to explain what was being written down.

The family was discussed at the case conference on Wednesday lunchtime, attended by the psychiatrist, nurse, paediatrician and allied health representatives. Mark was a focus of discussion, including considering whether he might be showing signs of depression and also how to best support and include him. As the problem had been revealed, suggesting one or both children might be at risk, a report was made to the Department of Family and Community Services. The case conference also discussed options for follow-up through services in the family’s community.

Carly had asked Mark to lead in parenting both children. The family joined the pram walk, and Mark was seen pushing Adam away. Adam refused to hold Mark’s hand on the walk back to the Unit. One nurse talked with him and suggested much of Adam’s behaviour is normal for a toddler, and that Mark might ‘pick his battles’ for what is important to him. Both the nurses and playroom coordinators noted how Mark, unlike Carly, doesn’t seem to know how to praise Adam. The afternoon shift reported that despite Carly’s encouragement, Mark had been very disengaged, even from Lizzie. He was reluctant to try tummy time to help stretch Lizzie’s waking period, saying he wanted to put her down earlier in order to have his lunch. Lizzie was difficult to settle. That afternoon, Adam defecated in the playroom, and Mark took him to a bathroom to clean up. Mark became angry; Adam bit Mark, and ran out seeking Carly. Carly found this very upsetting, and stood with Mark, away from Adam, calling her son over. The nurse on hand suggested she might go up to him and offer him a cuddle. Later they discussed again the idea of Mark preparing bottles, but he ‘flatly refused’.

On Thursday morning, there was an altercation between Carly and Mark over Lizzie’s solid intake, after Mark once again walked out at a meal time. However, Mark did spend time with a nurse working on preparing bottles for feeding Lizzie. While printed materials were given to Carly (who can read them), the nurse helped Mark put special marks on the bottle that he could use. Carly was pleased, and the nurses reflected that Mark’s reluctance may have been out of embarrassment or disempowerment relating to his illiteracy. They later talked to Mark about being guided by Lizzie’s cues, settling her when she displayed tired signs, rather than being guided according to his meal times or cigarette urges. He accepted this, and Lizzie went down later and slept for longer than the previous night. Her naps and feeds became more routinized during the daytime. On Thursday afternoon, Adam’s behaviour was much calmer, he was playing well and Mark made visible attempts to praise him. Adam was settled easily by Carly at night.

Discussion: The Intramediated Problem Space of Practice in Partnership

In the Unit’s work with the family, there were three problems of practice in play: the family, professional–family relationships and outcomes. I see these as dimensions of a single complex evolving object, mediating each other. These map closely onto the concepts of common knowledge, relational expertise and relational agency.

The team’s understanding of what mattered to the family changed daily, becoming increasingly layered, establishing that common knowledge was a nonlinear, recursive process of expansive learning. Different professionals interacted with the family, later exchanging narratives in handovers and case conferences that bring distributed interpretations and actions together. As well as learning what mattered to the family, the staff came to recognise their strengths and vulnerabilities: Carly’s ability to praise, Mark’s illiteracy. This further expanded interpretations of what matters and why, as when Mark’s lack of interest in bottle feeding was understood as a lack of perceived agency, because he associated preparing bottles with a need to read and write. This new knowledge had implications for their relational work with the family, helping them to imagine new possibilities.

The team was also constantly monitoring its relationship with the family. How can we include Mark? How can we reduce their concerns about being judged when we write about them? Note how the nurses initially followed Mark’s lead in trying to settle Lizzie early, at a time when he was pushing back against the staff; later on, after the success with using marks on the bottle, the relationship provided a basis for professionals to work with him in guided change to routines and feeding practices. Relational expertise is discussed across the team in terms of the affordances it creates for current action and in terms of further relational work needed. It may enrich common knowledge or help practitioners realise where current understandings of what matters require further work.

Finally, the team never lost sight of outcomes for families: progressing towards their goals (which were themselves shifting) and developing resilience. Over the course of the week, they noted changes in the ease with which Lizzie could be (re)settled, Adam’s improved temperament, and Mark’s involvement with both children. The focus was not just the nature and extent of change, but why this was so and how this was known. The narrative accounts presented in handovers and case conferences mediated how the team made sense of what happened, what they knew (and didn’t know) and what to do next. These narratives operated as ‘why’ and ‘where to’ tools (Edwards, Reference Edwards2011; Edwards & Daniels, Reference Edwards and Daniels2012; Edwards et al., Reference Edwards, Kinti, Daniels, Edwards, Engeström, Gallagher and Ludvigsen2010; Engeström, Reference 41Engeström2007a, Reference Engeström, Daniels, Cole and Wertschb). That is, they were tertiary artefacts, presenting possibilities of imagined worlds rather than merely reflecting or organizing what already is (Wartofsky, Reference Wartofsky1973). Discussions were future-oriented, using representations of the past and category work (e.g. concepts of depression, normal toddler behaviour, illiteracy) to explore reasons and motives (‘whys’), which in turn helped to expand possible next steps and inform judgements as to an appropriate course of action (‘where tos’). Such discussions were mediated by common knowledge and relational expertise.

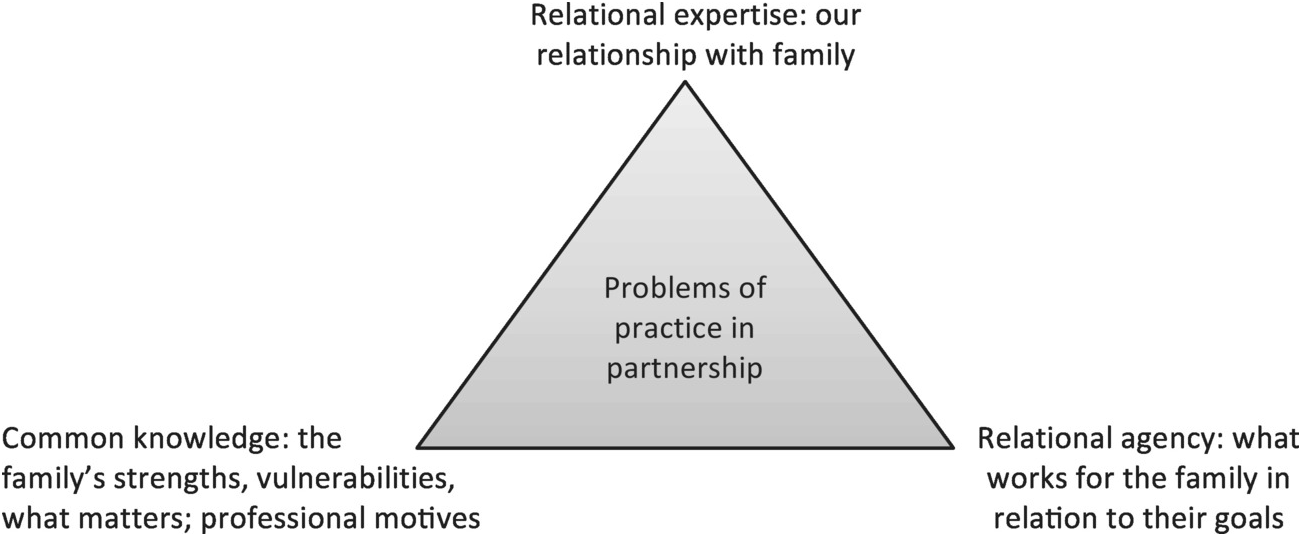

Expanding understanding of what mattered enabled adaptive, responsive practices (Edwards, Reference Edwards2012). Figure 2.1 represents this problem space of practice. Changing knowledge of each point provides a shifting basis for actions in practice, as well as a changing basis for (re)interpreting the other two. I conceive the family as a single object, intramediated by the three points. These are dialectical relationships of reverse action: two mediate the third, while a change in one has implications for the other two. This is in contrast to seeing them in linear sequence, or interconnected but separate domains of professional learning and expertise. The problem of practice is mediated by common knowledge, relational expertise and relational agency.

Figure 2.1. The intramediated problem of practice for professionals working in partnership with families.

The three points of the triangle in Figure 2.1 mediate each other, enabling expanded interpretations of and actions on an unstable object of activity. It may helpful to conceive this kind of partnership work as framed around families as knowledge objects, where the family contributes to the knowledge work. I use the term here in the same sense in which Edwards and Daniels (Reference Edwards and Daniels2012) developed Knorr Cetina’s (Reference Knorr Cetina1997, Reference Knorr Cetina1999; Knorr Cetina & Brueggar, Reference Knorr Cetina and Brueggar2002) ideas. The family is the focus of professional knowledge work, not as a stable thing to be known, but rather as an object that unfolds and draws professionals into epistemic work. In partnership, the family is discussed in a way that is generative of questions, and those questions are not all directly about the family. Rather, those questions are mediated: they are about the nature, status and extent of what is known about the family, relationships between professionals and the family and what appears (for now) to be working for them. The family is not a thing to be known, but rather a focus of knowledge work. This knowledge work is done through handover and case conference activities as sites of knowledge making and professional learning, through exchanges of narratives rather than exchange of information. Through FPM, families pull professionals into mediated knowledge work.

There is thus a sense in which the family also constitutes a runaway object (Engeström, Reference Engeström, Beyerlein, Beyerlein and Kennedy2005). The goals that matter to parents change, but they alone do not define the problem space for practice. Conceived in the triangular sense conveyed in Figure 2.1, the object constantly runs ahead of practice, even when a shift or set of interactions is framed around a goal that has been expressed by a family beforehand. These professionals responded to such runaway objects not by trying to hold them still, but through practices that embraced their elusiveness.

This brings us to relational agency. The professional expertise in play here includes stable bodies of core specialist expertise (the psychiatrist’s understandings of depression, nurses’ understandings of safe bottle feeding etc), relational expertise (framed here in terms of the FPM) and emerging expertise in the mediated problem of practice. This kind of partnership creates solution spaces as ‘sites of action’ (Edwards et al., Reference Edwards, Kinti, Daniels, Edwards, Engeström, Gallagher and Ludvigsen2010). These require collective input of the multiprofessional team and direct work with families. Attuning to handholding on the way back from the pram walk, temperatures of bottles and the strengths within families was folded into the joint construction of solutions. Each professional expanded interpretations of a particular goal and guided actions in relation to it. These become part of a wider object of activity (see Figure 2.1), where the professional team worked together, fuelling expansive learning, recognising the resources brought by different members of the team and parents.

The question of how to align responses to these shifting, expanded interpretations is not simply one of coordination for consistency across the team. Alignment is not always self-evident and is never totally secure. As the account of working with Carly and Mark shows, current interpretations are always provisional. Common knowledge and relational expertise mediate expansive learning of what works for a family and why.

I argue that the professional team coped with the fragile epistemic basis of their work in three linked ways:

1. Constructing the family as a runaway object, pulling the team into knowledge or epistemic work.

2. Recognising narrative exchange as a tertiary artefact that raised questions of ‘why’ and ‘where to’, exploring possibilities beyond the status quo.

3. Pursuing this knowledge work in relation to a problem of practice that is mediated by common knowledge, relational expertise and relational agency.

Despite the professionals’ robust specialist expertise, partnership work constantly provokes epistemic work that must confront conditions of incompleteness, provisionality and instability in what is known. The basis upon which to act cannot be exclusively located in the realm of core expertise. It can be accounted for only in terms of agile, emergent and adaptive relational work, co-configured around unstable, intramediated problems of practice.

Reflections on the Concepts in Use

Partnerships between professionals and families are central to respectful services, helping mitigate the effects of disadvantage and building resilience in families. Models of care, such as FPM, translate ambitious visions and often ambiguous policy rhetoric into specific ways of working. By applying the ideas of common knowledge, relational expertise and relational agency, we can see how partnership work intensifies the forms of professional expertise required. The rejection of ‘expert-led’ models in favour of relational, negotiated modes of working may challenge practices. Yet Edwards’ suite of concepts, within a broader CHAT framework, provides precise ways to elucidate partnership work and to get a firm analytical grip on the ‘heart’ of effective partnership work and the fluid horizontal linkages (Edwards, Reference Edwards2012) that emerge.

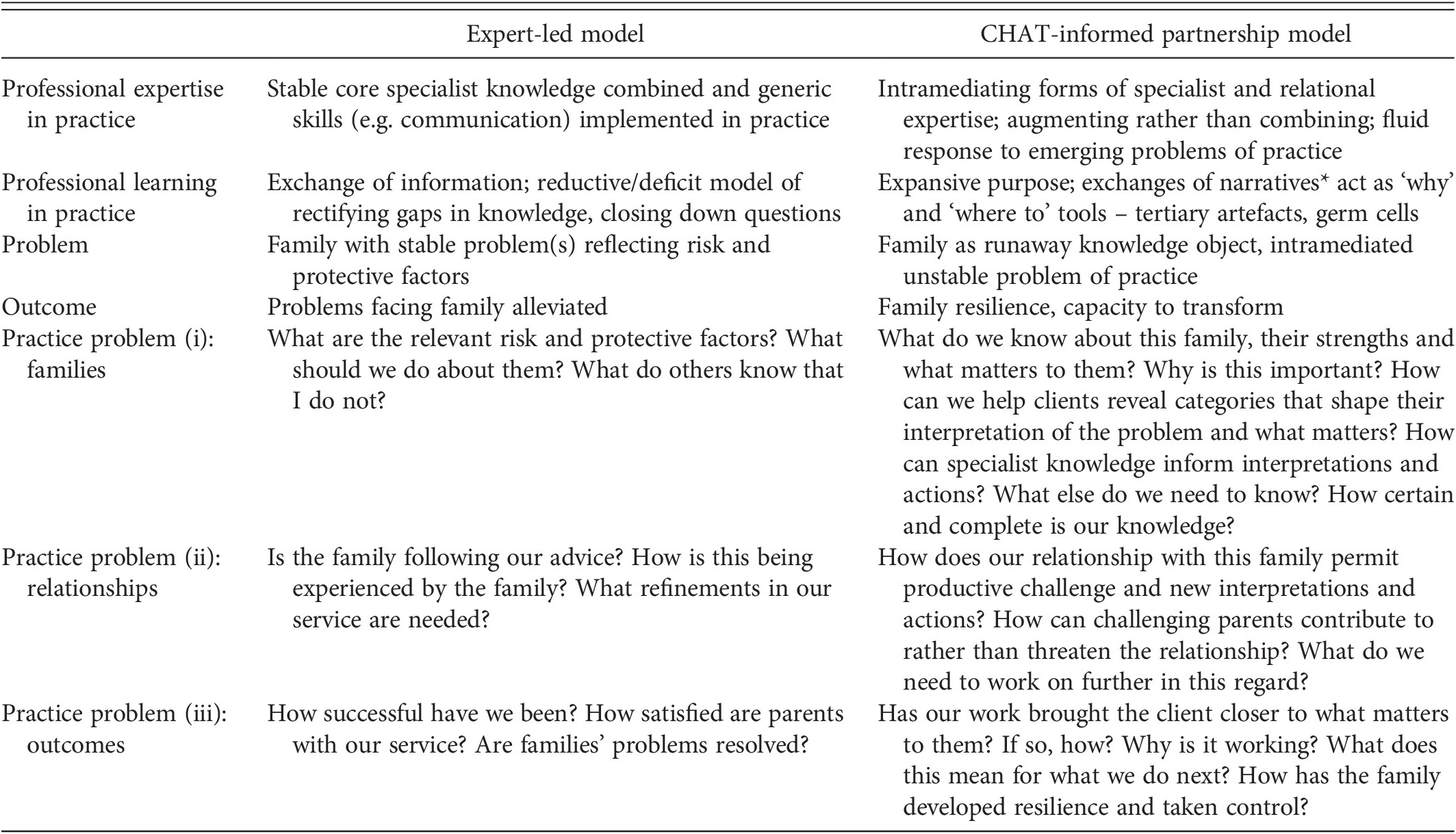

Building on Figure 2.1, Table 2.1 contrasts a partnership approach conceptualized using CHAT, with an expert-led model. While the latter is somewhat artificial, it highlights the moves at play. Such contrasts also show how the kind of work discussed here is not easy, suggesting the need for a refreshed view of professional expertise. Table 2.1 therefore elucidates frequently unarticulated features of partnership work, further highlighting the value of the relational concepts.

| Expert-led model | CHAT-informed partnership model | |

|---|---|---|

| Professional expertise in practice | Stable core specialist knowledge combined and generic skills (e.g. communication) implemented in practice | Intramediating forms of specialist and relational expertise; augmenting rather than combining; fluid response to emerging problems of practice |

| Professional learning in practice | Exchange of information; reductive/deficit model of rectifying gaps in knowledge, closing down questions | Expansive purpose; exchanges of narratives* act as ‘why’ and ‘where to’ tools – tertiary artefacts, germ cells |

| Problem | Family with stable problem(s) reflecting risk and protective factors | Family as runaway knowledge object, intramediated unstable problem of practice |

| Outcome | Problems facing family alleviated | Family resilience, capacity to transform |

| Practice problem (i): families | What are the relevant risk and protective factors? What should we do about them? What do others know that I do not? | What do we know about this family, their strengths and what matters to them? Why is this important? How can we help clients reveal categories that shape their interpretation of the problem and what matters? How can specialist knowledge inform interpretations and actions? What else do we need to know? How certain and complete is our knowledge? |

| Practice problem (ii): relationships | Is the family following our advice? How is this being experienced by the family? What refinements in our service are needed? | How does our relationship with this family permit productive challenge and new interpretations and actions? How can challenging parents contribute to rather than threaten the relationship? What do we need to work on further in this regard? |

| Practice problem (iii): outcomes | How successful have we been? How satisfied are parents with our service? Are families’ problems resolved? | Has our work brought the client closer to what matters to them? If so, how? Why is it working? What does this mean for what we do next? How has the family developed resilience and taken control? |

Table 2.1 shows how in partnership the problem of practice can be reshaped. Partnership work is driven by questions that refer to knowledge and yet never escape the heat of action and the ultimate requirement to produce positive change by building the capacity in families to transform their worlds. It is on this point that I return to one of mothers, whose letter I quoted earlier. She did not come to participate in expert practices, but changed her interpretations, which formed the basis of new actions and a capacity to transform life for her family, through pedagogies that reflect the quotation from Ellsworth with which I began:

What an amazing experience it was to find that all I had to do was trust. Trust in the three most important people in this story! Me, my partner and my baby. Karitane helped me to learn to trust in both myself and my partner. To realise that we are indeed, and have been all along, really great parents! … Since returning home, Tom, Fabi and I have done really well. Our baby is sleeping in his cot at night (and even in the day!) and his daddy can put him to bed awake now too! Fabi may still wake up to twice a night, but we know how to deal with it now, and how to read his cues. As his mum I have so much more energy in the day to enjoy my baby!! My baby is not textbook, but what good part of life ever is?! Sometimes in life I think we just need someone to help us turn the mirror back towards us to remind us of the strength we have inside (it is a heavy mirror to turn alone when you are so tired!).