Despite numerous global initiatives on breast-feeding, trend data show exclusive breast-feeding (EBF) rates have stagnated over the last two decades( Reference Victora, Bahl and Barros 1 , 2 ). In low- and middle-income countries, only 37 % of children younger than 6 months of age are exclusively breast-fed, defined as the proportion of infants aged 0–5 months who are fed only with breast milk and no additional liquids or solids until 6 months of life( Reference Victora, Bahl and Barros 1 ). Optimal breast-feeding practices have long been known to reduce neonatal and child mortality. Morbidities such as respiratory infections, diarrhoea and otitis media are also decreased, and growing evidence indicates breast-feeding may be protective against obesity and diabetes( Reference Victora, Bahl and Barros 1 , Reference Black, Allen and Bhutta 3 ). Breast-feeding has maternal benefits, contributing to birth spacing, and longer durations are associated with reductions in ovarian and breast cancer( Reference Victora, Bahl and Barros 1 ). Although some countries have made gains in EBF, early initiation and EBF rates in many countries are drastically below global targets( 4 – 6 ). Key challenges to EBF remain unaddressed through infant and young child feeding (IYCF) programming. A recent UNICEF report notes that 43 % of newborn babies are fed prelacteal foods or liquids (feeds given to a newborn before breast-feeding is established), which can delay early initiation of breast-feeding, reduce a child’s demand for breast milk and lead to difficulties in establishing breast-feeding( 6 ). In addition, most infants are introduced to other foods or liquids too early, prior to the recommended 6 months of age( 6 – 8 ). The objectives of the present systematic review were (i) to ascertain barriers to EBF in twenty-five low- and middle-income countries according to three domains: maternal issues (prenatal barriers); barriers encountered on the first day, including initiating and establishing EBF; and barriers encountered in maintaining EBF over the first 6 months of life; and (ii) to summarize the programme implications of these findings( 9 ).

Methods

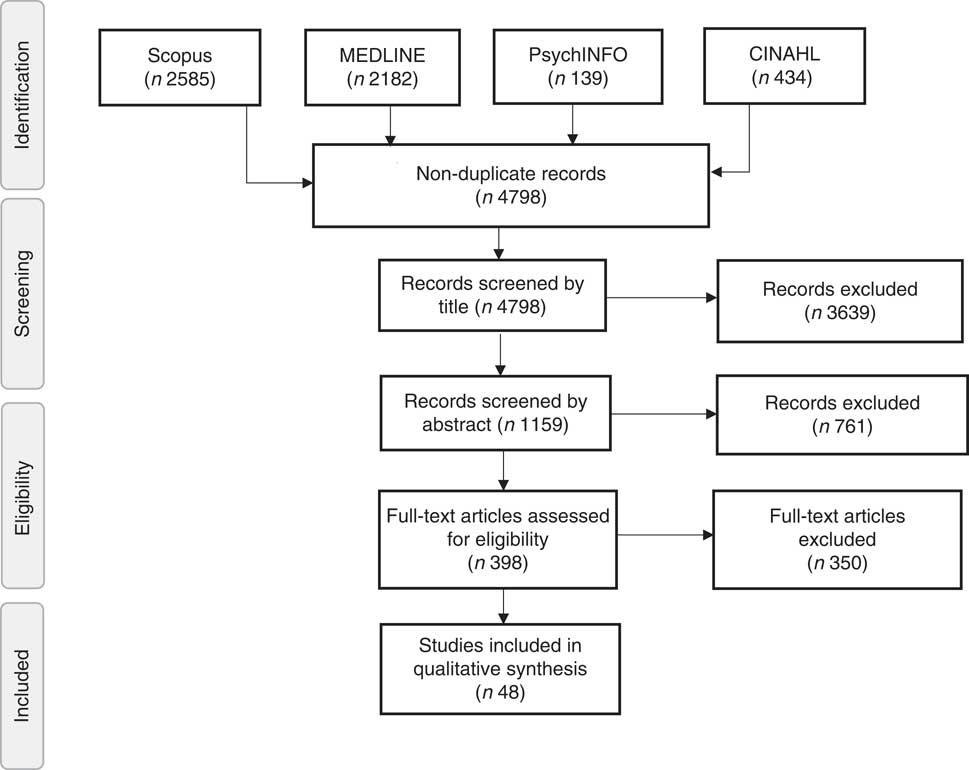

The purpose of the present systematic review was to determine barriers to EBF in twenty-five US Agency for International Development (USAID) ending preventable child and maternal deaths (EPCMD) priority countries.Footnote * The review was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (see Fig. 1 for the PRISMA flow diagram showing selection of studies).

Fig. 1 PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta Analyses) flow diagram: schematic representation of the selection of studies for the present systematic literature review on barriers to exclusive breast-feeding in low- and middle-income countries

Inclusion criteria

To be included in the present review, studies were required to report: (i) data collected on or after 1 January 2000; (ii) human data; (iii) infants as generally healthy; (iv) primary data collection by a researcher, which was inclusive of dissertations and grey literature (non-published documents, such as government, academic or organizational materials); (v) data and findings in Spanish, English or French; and (vi) data from any of the twenty-five USAID EPCMD priority countries.

Exclusion criteria

Studies were excluded if: (i) infants were reported as ill, premature and/or unhealthy; (ii) reported outcomes did not include EBF; (iii) data included intent to breast-feed without data on EBF practices; (iv) only demographic characteristics of the mother (age, socio-economic status, religion and geographic location) and no other information on EBF were reported; or (v) they were systematic or other reviews.

Search strategy and data extraction process

Four electronic databases, Scopus, MEDLINE, CINAHL and PsychINFO, were searched in September and October 2015 to find eligible studies (see Table 1 for a list of search terms). All search results were first screened by title, and then by abstract, for relevance. The remaining 398 full texts were retrieved for all remaining citations. The texts were evaluated using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) quality criteria by E.L., H.D. and J.A.K.( 10 ), which assessed the methodological quality of relevant studies, including study bias. Raters independently assessed the quality of each study, individual ratings were compared and consensus reached on each criterion. Any disagreements in ratings were discussed until the reviewers reached consensus.

Table 1 Literature search strategy for the present systematic literature review on barriers to exclusive breast-feeding in low- and middle-income countries

Structured forms were developed to extract information from each article, including study design, outcomes and results (quantitative and qualitative). Data were grouped by subject matter. For the quantitative data extraction, following grouping, data were mined by level of analysis (univariate, bivariate and multivariate), with the highest level of analysis reported and assessed. Data extraction was carried out by E.L., H.D. and J.A.K.

Results

Following application of the systematic review criteria, from the 4798 records originally identified, forty-eight articles were included in the final review (see Fig. 1). Sixteen barriers to EBF were identified (see Tables 2–4) and grouped according to three categories: (i) prenatal barriers; (ii) barriers at childbirth and during the first day of life; and (iii) barriers in the first 6 months of life. The most frequently reported barrier was ‘maternal employment’ (n 23) and the least reported was ‘planned length of EBF’ (n 2). Of the twenty-five USAID EPCMD priority countries, fourteen – including Bangladesh, Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Ghana, India, Indonesia, Kenya, Malawi, Nepal, Nigeria, Pakistan, Senegal, Tanzania and Uganda–were represented in the current systematic review. About one-third of the studies were reported from Nigeria (n 11) and India (n 10). Qualitative data illustrating various barriers are shown in Table 5.

Table 2 Matrix of reviewed papers addressing maternal barriers to exclusive breast-feeding (EBF) in low- and middle-income countries

ANC, antenatal care; DRC, Democratic Republic of Congo.

Table 3 Matrix of reviewed papers addressing barriers to exclusive breast-feeding (EBF) during the first day of life in low- and middle-income countries

DRC, Democratic Republic of Congo.

Table 4 Matrix of reviewed papers addressing continued barriers to exclusive breast-feeding (EBF) in the first 6 months of life in low- and middle-income countries

DRC, Democratic Republic of Congo.

Table 5 Selected quotes from qualitative studies addressing barriers to exclusive breast-feeding (EBF) in low- and middle-income countries

FGD, focus group discussion; IDI, in-depth interview.

Prenatal-related barriers to exclusive breast-feeding

Lack of or late attendance at antenatal care

Antenatal care (ANC) offers an opportunity to counsel women on EBF, among other health topics, in preparation for childbirth and the postpartum period. Fifteen studies described the relationship between ANC attendance and maternal report of EBF. Measurement of ANC attendance varied across studies and included: attendance at any ANC visit, frequency of ANC visits and attendance for a designated number of visits (i.e. <3 or ≥4 visits). Ten studies were cross-sectional( Reference Chandrashekhar, Joshi and Binu 11 – Reference Susiloretni, Krisnamurni and Sunarto 20 ), three were mixed-methods( Reference Setegn, Belachew and Gerbaba 21 – Reference Maonga, Mahande and Damian 23 ) and two were prospective cohort studies( Reference Babakazo, Donnen and Akilimali 24 , Reference Khanal, Lee and Karkee 25 ). Five cross-sectional studies reported a significant positive association between ANC attendance and EBF( Reference Matovu, Kirunda and Rugamba-Kabagambe 14 – Reference Ugboaja, Berthrand and Igwegbe 16 , Reference Ogunlesi 18 , Reference Susiloretni, Krisnamurni and Sunarto 20 ). Women with attendance at any ANC visit were twice as likely to practise EBF compared with women who did not attend ANC (36·4 v. 18·2 %, respectively; P=0·00, χ 2 test)( Reference Ugboaja, Berthrand and Igwegbe 16 ). Women attending four or more ANC visits in Uganda had 3·86 greater odds (95 % CI 1·82, 8·31) of practising EBF than women who attended fewer than four ANC visits( Reference Matovu, Kirunda and Rugamba-Kabagambe 14 ). Similarly, in Ethiopia, women who attended two or three ANC visits were twice as likely (95 % CI 1·18, 3·45) to practise EBF than those who only visited once( Reference Susiloretni, Krisnamurni and Sunarto 20 ).

Poor maternal knowledge of exclusive breast-feeding

Twelve studies examined the relationship between maternal knowledge of EBF and EBF practices, including seven cross-sectional( Reference Egata, Berhane and Worku 12 , Reference Ugboaja, Berthrand and Igwegbe 16 , Reference Onah, Osuorah and Ebenebe 19 , Reference Susiloretni, Krisnamurni and Sunarto 20 , Reference Tamiru, Belachew and Loha 22 , Reference Diagne-Guéye, Diack-Mbaye and Dramé 26 , Reference Yotebieng, Chalachala and Labbok 27 ), two mixed-methods( Reference Maonga, Mahande and Damian 23 , Reference Haider, Rasheed and Sanghvi 28 ), one cohort( Reference Babakazo, Donnen and Akilimali 24 ), one longitudinal( Reference Arusei, Ettyang and Esamai 29 ) and one qualitative study( Reference Aluko-Arowolo and Adekoya 30 ). Definitions of maternal knowledge of EBF varied across studies and included: maternal report of EBF definition and related benefits, recommendations and/or best practices. Only three studies found a significant association between maternal knowledge and EBF practices( Reference Egata, Berhane and Worku 12 , Reference Maonga, Mahande and Damian 23 , Reference Babakazo, Donnen and Akilimali 24 ).

In Ethiopia, a large cross-sectional study found that mothers with low knowledge of breast-feeding ‘best practices’ had 3·4 times higher odds of non-EBF than mothers with high knowledge of breast-feeding best practices( Reference Egata, Berhane and Worku 12 ). A mixed-methods study in Tanzania (n 316) found that those with ‘good’ breast-feeding knowledge had 2·15 times higher odds of EBF compared with those with poor knowledge( Reference Maonga, Mahande and Damian 23 ). In Democratic Republic of Congo, a prospective study revealed that mothers who had a low level of knowledge about breast-feeding had significantly lower odds of EBF at 6 months( Reference Babakazo, Donnen and Akilimali 24 ).

Maternal health and attitudes

Six studies examined the relationship between maternal health and attitudes regarding desire and ability to breast-feed and EBF practices, including four cross-sectional studies( Reference Mahmood, Srivastava and Shrotriya 13 , Reference Ugboaja, Berthrand and Igwegbe 16 , Reference Adeyinka, Ajibola and Oyesoji 31 , Reference Sohag and Memon 32 ), one cohort study( Reference Babakazo, Donnen and Akilimali 24 ) and one qualitative study( Reference Otoo, Lartey and Pérez-Escamilla 33 ). Measures of maternal health and attitudes differed across studies and included personal frustrations, confidence in one’s ability to breast-feed, stress and maternal illness. A cohort study found that Congolese women who described themselves as ‘not confident’ in their ability to breast-feed were more likely to cease EBF than those who reported being ‘very confident’ (adjusted hazard ratio=3·9; P=0·002)( Reference Babakazo, Donnen and Akilimali 24 ). Congolese women’s attitudes towards breast-feeding, whether positive or negative, were not found to affect EBF practices( Reference Babakazo, Donnen and Akilimali 24 ). Up to one-third of mothers in Pakistan, Nigeria and Ghana reported ceasing breast-feeding for their own physical or mental health, indicating that breast-feeding was a stressful, frustrating and/or painful experience, due to illness or breast problems( Reference Ugboaja, Berthrand and Igwegbe 16 , Reference Adeyinka, Ajibola and Oyesoji 31 , Reference Sohag and Memon 32 ).

Lack of intention to practise exclusive breast-feeding

Two studies examined the relationship between having a plan to exclusively breast-feed and EBF practices( Reference Babakazo, Donnen and Akilimali 24 , Reference Seid, Yesuf and Koye 34 ). A cohort study found that women with a prenatal EBF plan had 3·75 times higher likelihood of practising EBF than those who did not( Reference Seid, Yesuf and Koye 34 ). A large cross-sectional study in Democratic Republic of Congo found that women who had no planned length of EBF were 2·9 times more likely to discontinue EBF than those who planned to breast-feed exclusively( Reference Babakazo, Donnen and Akilimali 24 ).

Barriers to exclusive breast-feeding: first day of life

Delivery outside a health facility

Sixteen studies examined the relationship between the place of birth and EBF practices. Thirteen studies were cross-sectional( Reference Chandrashekhar, Joshi and Binu 11 , Reference Mahmood, Srivastava and Shrotriya 13 – Reference Tiwari, Mahajan and Lahariya 15 , Reference Joshi, Angdembe and Das 17 , Reference Ogunlesi 18 , Reference Susiloretni, Krisnamurni and Sunarto 20 , Reference Seid, Yesuf and Koye 34 – Reference Kishore, Kumar and Aggarwal 39 ), two were cohort studies( Reference Ukegbu, Ukegbu and Onyeonoro 40 , Reference Kimani-Murage, Madise and Fotso 41 ) and one was a mixed-methods study( Reference Maonga, Mahande and Damian 23 ). Seven studies found a significant and positive association between delivery in a health facility and EBF practices( Reference Chandrashekhar, Joshi and Binu 11 , Reference Mahmood, Srivastava and Shrotriya 13 , Reference Tiwari, Mahajan and Lahariya 15 , Reference Joshi, Angdembe and Das 17 , Reference Maonga, Mahande and Damian 23 , Reference Okanda, Borkowf and Girde 35 , Reference Kishore, Kumar and Aggarwal 39 ). Two studies in Ethiopia and Uganda found a two to three times higher likelihood of practising EBF in women who delivered in a health facility than those who delivered at home( Reference Seid, Yesuf and Koye 34 , Reference Ssenyonga, Muwonge and Nankya 38 ). Similarly, a cross-sectional study in Nigeria showed that those who delivered outside a health facility were less likely to practise EBF (OR=2·6; P=0·049)( Reference Ogunlesi 18 ).

Delivery by caesarean section v. vaginal birth

Fifteen studies examined the association between method of delivery and EBF practices: nine cross-sectional( Reference Chandrashekhar, Joshi and Binu 11 , Reference Matovu, Kirunda and Rugamba-Kabagambe 14 , Reference Tiwari, Mahajan and Lahariya 15 , Reference Joshi, Angdembe and Das 17 , Reference Onah, Osuorah and Ebenebe 19 , Reference Seid, Yesuf and Koye 34 , Reference Okanda, Borkowf and Girde 35 , Reference Sharma and Kanani 37 , Reference Ssenyonga, Muwonge and Nankya 38 ), four cohort( Reference Khanal, Lee and Karkee 25 , Reference Ukegbu, Ukegbu and Onyeonoro 40 , Reference Karkee, Lee and Khanal 42 , Reference Raghavan, Bharti and Kumar 43 ) and two mixed-methods studies( Reference Setegn, Belachew and Gerbaba 21 , Reference Maonga, Mahande and Damian 23 ). One study was observational and did not perform statistical analysis on the aforementioned association( Reference Ukegbu, Ukegbu and Onyeonoro 40 ). Six of these studies found a significant relationship between type of delivery and EBF practice( Reference Chandrashekhar, Joshi and Binu 11 , Reference Matovu, Kirunda and Rugamba-Kabagambe 14 , Reference Khanal, Lee and Karkee 25 , Reference Sharma and Kanani 37 , Reference Ssenyonga, Muwonge and Nankya 38 , Reference Karkee, Lee and Khanal 42 ).

Five studies found mothers were 2·28 to 10·54 times more likely to exclusively breast-feed following vaginal birth in comparison to infants delivered through caesarean section( Reference Chandrashekhar, Joshi and Binu 11 , Reference Matovu, Kirunda and Rugamba-Kabagambe 14 , Reference Seid, Yesuf and Koye 34 , Reference Sharma and Kanani 37 , Reference Ssenyonga, Muwonge and Nankya 38 ).

Two studies examined the relationship between caesarean birth and cessation of EBF( Reference Khanal, Lee and Karkee 25 , Reference Karkee, Lee and Khanal 42 ). A large study in Nigeria found that women who delivered by caesarean section were 29 % less likely to practise EBF than those who delivered vaginally( Reference Onah, Osuorah and Ebenebe 19 ). Similarly, in Nepal, study findings revealed that women with a vaginal delivery had 7·6 times greater likelihood of EBF than those who delivered via caesarean section (P=0·008)( Reference Chandrashekhar, Joshi and Binu 11 ).

Timing of initiation of breast-feeding: early v. delayed

Eight studies assessed the relationship between initiation of breast-feeding and the practice of EBF within the first 6 months, including four cross-sectional( Reference Matovu, Kirunda and Rugamba-Kabagambe 14 , Reference Tiwari, Mahajan and Lahariya 15 , Reference Susiloretni, Krisnamurni and Sunarto 20 , Reference Meshram, Laxmaiah and Venkaiah 44 ), two prospective cohort studies( Reference Khanal, Lee and Karkee 25 , Reference Raghavan, Bharti and Kumar 43 ), one mixed-methods( Reference Maonga, Mahande and Damian 23 ) and one longitudinal study( Reference Arusei, Ettyang and Esamai 29 ). Five studies found a significant positive association between early initiation of breast-feeding, defined as within the first hour following childbirth, and the continued practice of EBF at 6 weeks, 10 weeks and 6 months after birth( Reference Matovu, Kirunda and Rugamba-Kabagambe 14 , Reference Tiwari, Mahajan and Lahariya 15 , Reference Arusei, Ettyang and Esamai 29 , Reference Raghavan, Bharti and Kumar 43 , Reference Meshram, Laxmaiah and Venkaiah 44 ).

A study in Uganda reported that women who initiated breast-feeding early were more likely to adhere to EBF than women who delayed initiation for more than an hour following childbirth (adjusted OR=10·17; 95 % CI 4·52, 22·88)( Reference Matovu, Kirunda and Rugamba-Kabagambe 14 ). In India, findings from a cohort study revealed that women who initiated breast-feeding more than an hour after birth were at a higher risk of ceasing EBF by 6 weeks (relative risk=1·77; 95 % CI 1·1, 2·84)( Reference Raghavan, Bharti and Kumar 43 ). This same study named maternal perception of inadequacy of milk, nipple problems, pain and difficulty in sitting up, and breast refusal as challenges that play a role in the decision to delay initiation of breast-feeding beyond the first hour of life( Reference Raghavan, Bharti and Kumar 43 ).

Prelacteal feeding

Prelacteal feeding is defined as giving foods and/or liquids, other than colostrum, to an infant prior to establishing breast-feeding. Seven studies examining prelacteal feeding and EBF practices were identified, with five cross-sectional studies, one qualitative and one cohort study( Reference Egata, Berhane and Worku 12 , Reference Joshi, Angdembe and Das 17 , Reference Onah, Osuorah and Ebenebe 19 , Reference Susiloretni, Krisnamurni and Sunarto 20 , Reference Ukegbu, Ukegbu and Onyeonoro 40 , Reference Meshram, Laxmaiah and Venkaiah 44 , Reference Engebretsen, Moland and Nankunda 45 ). Observational data revealed that prelacteal feeding prevalence ranges from 13 to 76 %, depending on the country context. Glucose water, infant formula, honey, cow’s or buffalo’s milk, or water were cited as common prelacteal feeds( Reference Egata, Berhane and Worku 12 , Reference Joshi, Angdembe and Das 17 , Reference Onah, Osuorah and Ebenebe 19 , Reference Susiloretni, Krisnamurni and Sunarto 20 , Reference Meshram, Laxmaiah and Venkaiah 44 , Reference Engebretsen, Moland and Nankunda 45 ). In Ethiopia, although 76 % of mothers gave prelacteal feeds, prelacteal feeding was not associated with non-EBF, following bivariate analyses( Reference Egata, Berhane and Worku 12 ). In Nigeria, a large cross-sectional study showed that when breast milk was given as first feed, women had a 3·4 times higher likelihood of EBF (95 % CI 1·75, 6·66) compared with infant formula as a first feed, which lowered likelihood of EBF by 46 %( Reference Onah, Osuorah and Ebenebe 19 ).

Colostrum feeding practices – discarding of the colostrum

Nine studies examined whether feeding colostrum, the ‘first milk’, is associated with EBF. This included seven cross-sectional studies( Reference Chandrashekhar, Joshi and Binu 11 , Reference Egata, Berhane and Worku 12 , Reference Tiwari, Mahajan and Lahariya 15 , Reference Joshi, Angdembe and Das 17 , Reference Onah, Osuorah and Ebenebe 19 , Reference Susiloretni, Krisnamurni and Sunarto 20 , Reference Meshram, Laxmaiah and Venkaiah 44 ), one mixed-methods( Reference Tamiru, Belachew and Loha 22 ) and one cohort study( Reference Ukegbu, Ukegbu and Onyeonoro 40 ). Two studies found a statistically significant association between providing or discarding colostrum and the likelihood of EBF( Reference Chandrashekhar, Joshi and Binu 11 , Reference Tamiru, Belachew and Loha 22 ).

In Ethiopia, discarding colostrum was associated with higher odds of non-EBF during the first 6 months (adjusted OR=1·78; 95 % CI 1·09, 4·94), after taking confounding variables into account( Reference Tamiru, Belachew and Loha 22 ). In Nepal, a multivariate analysis showed that women who fed colostrum had a 27·2 times greater likelihood of EBF for 6 months compared with those who gave other foods as a first feed (P<0·001)( Reference Chandrashekhar, Joshi and Binu 11 ). Reasons reported for discarding colostrum included receipt of advice from elders, that it was ‘not good for health’, ‘the child could get sick’ and that colostrum was ‘difficult for child to digest’( Reference Meshram, Laxmaiah and Venkaiah 44 ).

Barriers to maintaining exclusive breast-feeding in the first 6 months of life

Maternal employment

Full-time employment may limit the ability of women to breast-feed their children, considering women without maternity leave, those who work long hours outside the home, those who perform physical labour or those without workplace protections, such as breaks for breast-feeding. Twenty-three studies examined maternal employment in relation to EBF practices, including fifteen cross-sectional( Reference Joshi, Angdembe and Das 17 – Reference Onah, Osuorah and Ebenebe 19 , Reference Diagne-Guéye, Diack-Mbaye and Dramé 26 , Reference Adeyinka, Ajibola and Oyesoji 31 , Reference Sohag and Memon 32 , Reference Seid, Yesuf and Koye 34 – Reference Ssenyonga, Muwonge and Nankya 38 , Reference Cherop, Keverenge-Ettyang and Mbagaya 46 – Reference Safari, Kimambo and Lwelamira 49 ), four qualitative( Reference Aluko-Arowolo and Adekoya 30 , Reference Otoo, Lartey and Pérez-Escamilla 33 , Reference Engebretsen, Moland and Nankunda 45 , Reference Kimani-Murage, Wekesah and Wanjohi 50 ), two mixed-methods( Reference Setegn, Belachew and Gerbaba 21 , Reference Maonga, Mahande and Damian 23 ) and two cohort studies( Reference Babakazo, Donnen and Akilimali 24 , Reference Khanal, Lee and Karkee 25 ). Definitions of maternal employment varied across the studies and included employment status, type of occupation, return to work following childbirth and/or employment cited as a barrier to EBF. Seven studies (six cross-sectional and one mixed-methods) reported a statistically significant association between maternal employment and EBF( Reference Ogunlesi 18 , Reference Setegn, Belachew and Gerbaba 21 , Reference Adeyinka, Ajibola and Oyesoji 31 , Reference Seid, Yesuf and Koye 34 , Reference Obilade 47 – Reference Safari, Kimambo and Lwelamira 49 ).

Five of these seven studies found women who self-defined as a housewife or as unemployed were more likely to practise EBF than woman who had formal employment( Reference Ogunlesi 18 , Reference Setegn, Belachew and Gerbaba 21 , Reference Seid, Yesuf and Koye 34 , Reference Olayemi, Aimakhu and Bello 48 , Reference Safari, Kimambo and Lwelamira 49 ). A cross-sectional study from Nigeria found that women who returned to work had a 51·8 % lower likelihood of practising EBF than those who did not (P<0·05)( Reference Olayemi, Aimakhu and Bello 48 ). A similar finding was reported in Nigeria among women professionals who did not practise EBF (P=0·024)( Reference Ogunlesi 18 ). In Ethiopia and Tanzania, three studies found that women who remained unemployed or were noted as housewives had between 2·2 and 10·4 times higher odds of practising EBF (compared with women in formal employment)( Reference Setegn, Belachew and Gerbaba 21 , Reference Seid, Yesuf and Koye 34 , Reference Safari, Kimambo and Lwelamira 49 ).

Perceptions of poor infant behaviour, health and cues of feeding problems

The perceived behaviours of an infant can be cues for a mother in regard to her decision and/or ability to exclusively breast-feed. Eleven studies examined perceived infant behaviours and/or health in relation to EBF practices. These included five cross-sectional( Reference Mahmood, Srivastava and Shrotriya 13 , Reference Adeyinka, Ajibola and Oyesoji 31 , Reference Sohag and Memon 32 , Reference Cherop, Keverenge-Ettyang and Mbagaya 46 , Reference Gewa, Oguttu and Savaglio 51 ), four qualitative( Reference Otoo, Lartey and Pérez-Escamilla 33 , Reference Engebretsen, Moland and Nankunda 45 , Reference Kimani-Murage, Wekesah and Wanjohi 50 , Reference Afiyanti and Juliastuti 52 ), one cohort( Reference Suresh, Sharma and Saksena 53 ) and one mixed-methods study( Reference Haider, Rasheed and Sanghvi 28 ). Infant behaviours and cues included interpretation of crying, fussiness, and perceived receipt of adequate nutrition for the infant and infant health, which included perceptions of health in relation to other infants of a similar age. Only one study performed a full multivariate analysis and found that maternal perception of infant health was not associated with breast-feeding practices( Reference Gewa, Oguttu and Savaglio 51 ). Cross-sectional studies reported the following reasons for not exclusively breast-feeding: infant gaining insufficient weight, colic, breast-feeding suckling difficulties and perceptions that infants were not satiated by breast-feeding( Reference Suresh, Sharma and Saksena 53 ).

Perceptions of insufficient breast milk

Nine studies examined the relationship of maternal perception of insufficient milk with EBF practices: four cross-sectional( Reference Mahmood, Srivastava and Shrotriya 13 , Reference Matovu, Kirunda and Rugamba-Kabagambe 14 , Reference Sohag and Memon 32 , Reference Cherop, Keverenge-Ettyang and Mbagaya 46 ), three qualitative( Reference Afiyanti and Juliastuti 52 , Reference Østergaard and Bula 54 , Reference Maman, Cathcart and Burkhardt 55 ), one mixed-methods( Reference Yotebieng, Chalachala and Labbok 27 ) and one cohort study( Reference Suresh, Sharma and Saksena 53 ). Five studies, inclusive of four cross-sectional and one cohort study, provided observational data on insufficient milk and related insufficient breast milk to EBF practices( Reference Mahmood, Srivastava and Shrotriya 13 , Reference Sohag and Memon 32 , Reference Cherop, Keverenge-Ettyang and Mbagaya 46 , Reference Suresh, Sharma and Saksena 53 ). A study conducted with Ugandan women reported that women who believed they could produce enough breast milk were 3·9 times more likely to practise EBF than women who believed their breast milk was ‘not enough’( Reference Matovu, Kirunda and Rugamba-Kabagambe 14 ). Insufficient milk or inadequate milk secretion was cited as a primary reason for ceasing to exclusively breast-feed and introduce other foods and liquids in two studies in India( Reference Mahmood, Srivastava and Shrotriya 13 , Reference Suresh, Sharma and Saksena 53 ). Qualitative data revealed mothers perceived their breast milk to be lacking in quantity to nourish infants and introduced other foods, such as porridge and fruit, as a way to satiate infants and calm cries of hunger or fussiness( Reference Afiyanti and Juliastuti 52 , Reference Østergaard and Bula 54 , Reference Maman, Cathcart and Burkhardt 55 ).

Perceived inadequate maternal nutrition

Five studies examined maternal diet and EBF: two cross-sectional( Reference Egata, Berhane and Worku 12 , Reference Kamudoni, Maleta and Shi 36 ), two qualitative( Reference Engebretsen, Moland and Nankunda 45 , Reference Kimani-Murage, Wekesah and Wanjohi 50 ) and one mixed-methods that used both quantitative and qualitative data( Reference Webb-Girard, Cherobon and Mbugua 56 ). Maternal nutrition was described within the context of household food insecurity and the ability to purchase food or the lack of staple foods (i.e. maize) for a period of time. Neither cross-sectional study found a significant association between maternal nutrition and EBF practices( Reference Egata, Berhane and Worku 12 , Reference Kamudoni, Maleta and Shi 36 ). Qualitative data described the linkage between mothers ‘eating well’ and ‘sufficient amounts of food’ and breast milk sufficiency (see Table 5)( Reference Engebretsen, Moland and Nankunda 45 , Reference Kimani-Murage, Wekesah and Wanjohi 50 , Reference Webb-Girard, Cherobon and Mbugua 56 ).

Breast-feeding problems

Seven studies examined the relationship between breast-feeding problems and EBF practices, including three cross-sectional studies( Reference Chandrashekhar, Joshi and Binu 11 , Reference Sohag and Memon 32 , Reference Safari, Kimambo and Lwelamira 49 ), three cohort studies( Reference Babakazo, Donnen and Akilimali 24 , Reference Karkee, Lee and Khanal 42 , Reference Suresh, Sharma and Saksena 53 ) and one qualitative study( Reference Otoo, Lartey and Pérez-Escamilla 33 ). Breast-feeding problems are defined as physical breast problems, which included mastitis, breast engorgement, and cracked or inverted nipples. Of the quantitative studies, three studies reported descriptive information( Reference Sohag and Memon 32 , Reference Safari, Kimambo and Lwelamira 49 , Reference Suresh, Sharma and Saksena 53 ), one reported bivariate analyses( Reference Karkee, Lee and Khanal 42 ) and two performed multivariate analysis( Reference Chandrashekhar, Joshi and Binu 11 , Reference Babakazo, Donnen and Akilimali 24 ). Two cohort studies found a significant negative association between breast-feeding problems and likelihood of EBF( Reference Babakazo, Donnen and Akilimali 24 , Reference Karkee, Lee and Khanal 42 ). In Democratic Republic of Congo, mothers with breast-feeding problems during the first week were 1·5 times more likely to cease EBF during the first 6 months than mothers without breast-feeding problems( Reference Babakazo, Donnen and Akilimali 24 ). Similarly, in Nepal, breast-feeding problems were significantly associated with cessation of EBF (adjusted hazard ratio=2·07; 95 % CI 1·66, 2·57; P<0·001) at 4, 12 or 22 weeks following delivery, and urban mothers were more likely than rural mothers to cease breast-feeding early( Reference Karkee, Lee and Khanal 42 ). In Tanzania and Pakistan, 4–12 % of mothers reported breast problems, such as engorgement, breast pain, cracked nipples and mastitis, as a contributing factor to non-EBF( Reference Sohag and Memon 32 , Reference Safari, Kimambo and Lwelamira 49 ). Focus group discussions with Ghanaian mothers described breast and nipple problems, including swollen and painful breasts, breast abscesses and sore nipples, as important barriers to EBF( Reference Otoo, Lartey and Pérez-Escamilla 33 ).

Counselling on breast-feeding

Fourteen studies examined the association between counselling on breast-feeding and EBF. These included nine cross-sectional studies( Reference Mahmood, Srivastava and Shrotriya 13 , Reference Matovu, Kirunda and Rugamba-Kabagambe 14 , Reference Ugboaja, Berthrand and Igwegbe 16 , Reference Joshi, Angdembe and Das 17 , Reference Adeyinka, Ajibola and Oyesoji 31 , Reference Seid, Yesuf and Koye 34 , Reference Sharma and Kanani 37 – Reference Kishore, Kumar and Aggarwal 39 ), two qualitative studies( Reference Kimani-Murage, Wekesah and Wanjohi 50 , Reference Østergaard and Bula 54 ), two cohort studies( Reference Khanal, Lee and Karkee 25 , Reference Raghavan, Bharti and Kumar 43 ) and one mixed-methods study( Reference Maonga, Mahande and Damian 23 ). Of the twelve quantitative studies, four studies reported a significant and positive association between counselling and EBF( Reference Matovu, Kirunda and Rugamba-Kabagambe 14 , Reference Khanal, Lee and Karkee 25 , Reference Seid, Yesuf and Koye 34 , Reference Sharma and Kanani 37 ). Two studies in Ethiopia reported that mothers who were counselled on infant feeding practices had a greater likelihood of exclusively breast-feeding( Reference Seid, Yesuf and Koye 34 , Reference Sharma and Kanani 37 ). A study in Nepal examined the effect of types of breast-feeding advice on cessation of EBF and found that mothers who received the advice ‘breast-feeding on demand’ and ‘not to provide pacifier or teats’ were less likely to cease EBF practice before 6 months( Reference Khanal, Lee and Karkee 25 ). In Uganda, one study showed that HIV-positive mothers benefited more from individual counselling than group counselling for improving EBF practices( Reference Matovu, Kirunda and Rugamba-Kabagambe 14 ).

Family and community support for exclusive breast-feeding

Seventeen studies examined the relationship between family and community support and EBF practices. Six studies were cross-sectional( Reference Chandrashekhar, Joshi and Binu 11 , Reference Matovu, Kirunda and Rugamba-Kabagambe 14 , Reference Ugboaja, Berthrand and Igwegbe 16 , Reference Adeyinka, Ajibola and Oyesoji 31 , Reference Otoo, Lartey and Pérez-Escamilla 33 , Reference Olayemi, Aimakhu and Bello 48 ), five were qualitative( Reference Aluko-Arowolo and Adekoya 30 , Reference Otoo, Lartey and Pérez-Escamilla 33 , Reference Engebretsen, Moland and Nankunda 45 , Reference Afiyanti and Juliastuti 52 , Reference Østergaard and Bula 54 ), three were cohort( Reference Khanal, Lee and Karkee 25 , Reference Ukegbu, Ukegbu and Onyeonoro 40 , Reference Suresh, Sharma and Saksena 53 ) and three were mixed-methods studies( Reference Yotebieng, Chalachala and Labbok 27 , Reference Haider, Rasheed and Sanghvi 28 , Reference Aubel, Touré and Diagne 57 ). Twelve of seventeen studies reported observational or qualitative data on types of family and community support (defined as presence of grandmothers in the household, grandmother’s and father’s feeding preferences, advice or preference from friends and/or the community, and/or husband’s assistance during breast-feeding) and EBF( Reference Ugboaja, Berthrand and Igwegbe 16 , Reference Khanal, Lee and Karkee 25 , Reference Yotebieng, Chalachala and Labbok 27 , Reference Haider, Rasheed and Sanghvi 28 , Reference Aluko-Arowolo and Adekoya 30 , Reference Adeyinka, Ajibola and Oyesoji 31 , Reference Otoo, Lartey and Pérez-Escamilla 33 , Reference Engebretsen, Moland and Nankunda 45 , Reference Afiyanti and Juliastuti 52 – Reference Østergaard and Bula 54 , Reference Aubel, Touré and Diagne 57 ). Seven of eight qualitative studies indicated that grandmothers have an influential role in infant feeding practices( Reference Yotebieng, Chalachala and Labbok 27 , Reference Haider, Rasheed and Sanghvi 28 , Reference Otoo, Lartey and Pérez-Escamilla 33 , Reference Raghavan, Bharti and Kumar 43 , Reference Afiyanti and Juliastuti 52 , Reference Østergaard and Bula 54 , Reference Aubel, Touré and Diagne 57 ). Most women described the grandmother (i.e. mother of study participant or mother-in-law) as a key influencer of feeding practices, either providing advice on early introduction of foods or actively feeding the infant during the first 6 months, with or without the mother’s consent (see Table 5).

Mothers reported that grandmothers preferred mothers to adopt the same feeding practices as their own generation( Reference Otoo, Lartey and Pérez-Escamilla 33 ).

Two studies reported a significant and positive association between family and community support and EBF( Reference Chandrashekhar, Joshi and Binu 11 , Reference Ukegbu, Ukegbu and Onyeonoro 40 ). In Nepal, having friends who exclusively breast-fed had a positive impact on the EBF practices of women( Reference Chandrashekhar, Joshi and Binu 11 ). In Nigeria, family attitudes towards EBF were examined( Reference Ukegbu, Ukegbu and Onyeonoro 40 ). Among women, 44 % who cited a family environment of positivity towards EBF practised EBF, while only 29 % of those who perceived a negative family attitude towards EBF practised it (P=0·028). In Nigeria, reasons for discontinuing or not practising EBF included it not being culturally acceptable, husband refusal to allow EBF or receipt of advice from elders to discontinue( Reference Ugboaja, Berthrand and Igwegbe 16 ). Social support was identified as an aid in continuing EBF in Nigeria and Ghana( Reference Adeyinka, Ajibola and Oyesoji 31 ).

Discussion

Our search of the academic and grey literature found sixteen barriers to EBF in the first 6 months of life in fourteen USAID EPCMD priority countries. These barriers were sub-categorized into prenatal barriers, barriers during the first 24 h after birth and barriers that extend through the first 6 months. Our analysis is congruent with recent findings on impediments to EBF practices( Reference Balogun, Dagvadorj and Anigo 58 , Reference Bevan and Brown 59 ). We conclude that there is moderate evidence (i.e. at least five studies) of a negative association between maternal employment and EBF due to mixed results from quantitative and qualitative studies. Data on intent to breast-feed were limited and it is unclear as to its effect on EBF practices.

Studies that investigated barriers at childbirth and the initial 24 h after delivery found strong evidence that type of delivery, particularly caesarean section, can impede EBF practices. The current review reveals moderate evidence for early initiation of breast-feeding and likelihood of practising EBF. Breast-feeding problems and perceived insufficient breast milk were commonly reported, yet data emanated from weak study designs (i.e. cross-sectional or observational). Our review reveals that counselling on EBF and the presence of family and/or community support have some impact on improved EBF practices, given that half of studies showed associations of significance. It is unclear as to the role of perceived infant behaviours/cues in EBF practices, given limited evidence.

Promising interventions and programmatic implications of the current review

Workplace support for breast-feeding

Half of the identified studies in our review demonstrated that support for EBF is challenging for women in formal employment. Our findings are similar those reported from Ethiopia, Kenya and Brazil, which show that women who self-define as ‘unemployed’ tend to have better EBF practices than their formally employed counterparts( Reference Egata, Berhane and Worku 12 , Reference Asemahagn 60 – Reference Nyanga, Musita and Otieno 62 ). Lack of on-site child care; absence of physical areas to support breast-feeding, such as breast-feeding rooms or breast pumps; and short maternity leave are common obstacles to EBF for working mothers( Reference Mlay, Keddy and Stern 63 – Reference Soomro, Shaikh and Saheer 65 ). Available global guidance for employers provides key actions to support breast-feeding in the workplace, to enforce country policies on paid maternity leave, and to facilitate a supportive working environment for breast-feeding( 66 – 68 ).

Caesarean delivery and exclusive breast-feeding

According to findings from the current review, giving birth by caesarean section is a substantial barrier to EBF practices. A recent systematic review reported that rates of early initiation of breast-feeding were lower after caesarean section compared with vaginal birth, and full/exclusive breast-feeding at 6 months was lower following caesarean delivery( Reference Prior, Santhakumaran and Gale 69 ). Practices surrounding caesarean deliveries may create barriers to EBF, including no skin-to-skin contact, separation of mother and infant, and delayed initiation of breast-feeding, which are compounded by longer recovery times and reported late onset of full lactation( Reference Ahluwalia, Li and Morrow 70 – Reference Chapman 72 ). Postpartum fatigue, pain and complications associated with caesarean delivery should also be considered regarding breast-feeding behaviours, which can contribute to early cessation of EBF( Reference Fein, Mandal and Roe 73 ). Mothers and families should receive encouragement and support for rooming-in of mother and infant, support to learn how to manually express breast milk during separation, and discouragement from use of formula for satiating hunger and from early cessation of breast-feeding, unless medically indicated.

Strengthening health-worker skills at health facilities and Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative

Our findings reveal the need to address difficulties with EBF, such as physical breast problems or perceptions of insufficient milk, so women can EBF for the full 6-month duration. Health workers play a critical role in EBF counselling and should be equipped with the necessary skills to address breast-feeding problems during ANC and postnatal care, especially in light of recent WHO ANC guidelines( 74 ). The development of practical, simple guidance and job aids on how to identify and address breast-feeding difficulties may aid overburdened health providers, who often face high demands on time and provide multiple services.

A recent systematic review of randomized controlled trials of the Baby-Friendly Hospital InitiativeFootnote * demonstrated improvements in any breast-feeding and EBF rates( Reference Sinha, Chowdhury and Sankar 75 – Reference Ojofeitimi, Esimai and Owolabi 77 ). Baby-friendly support, counselling, or education and special training of health staff provided through health facility services had a significant impact on improved EBF (for three interventions, relative risk range=1·33–1·66; 95 % CI 1·14, 1·92)( Reference Pérez-Escamilla 76 ). Studies supportive of our findings indicate that inadequate staff knowledge and practices related to breast-feeding, reliance on infant formula and clarification on which circumstances to use formula can contribute to inconsistent breast-feeding information from health facility providers, which needs to be addressed( Reference Semenic, Childerhose and Lauzière 78 , 79 ).

Kangaroo mother care, defined as skin-to-skin care, EBF and supportive care for the mother and baby dyad in health facilities, is also a key intervention for supporting EBF( Reference Engmann, Wall and Darmstadt 80 ), with evidence of its benefits on EBF rates and neonatal morbidity and mortality( Reference Conde-Agudelo and Díaz-Rossello 81 ). In addition, as part of a comprehensive breast-feeding package, a few studies have noted a positive correlation of increased breast-feeding rates in hospitals with human milk banks for vulnerable infants( Reference Bertino, Giuliani and Baricco 82 – Reference DeMarchis, Israel-Ballard and Mansen 85 ).

Strengthening family- and community-level interventions

A central finding from the current review is the identified need for improving and sustaining breast-feeding support at the household and community levels. Promotion, counselling and education on EBF in the health facility and community was deemed one of the ‘most powerful interventions’ examined to improve breast-feeding, showing a 152 % increase in EBF( Reference Pérez-Escamilla 76 ). Counselling as a single intervention in the community or by health staff demonstrated lower effects on EBF, suggesting the importance of linking communities with health facilities to support EBF( Reference Pérez-Escamilla 76 , Reference Semenic, Childerhose and Lauzière 78 ).

Strong implementation of the tenth step of the WHO/UNICEF 10 Steps of Successful Breast-feeding is a key aspect of sustaining gains in breast-feeding achieved in maternity wards beyond the day of birth, evidenced by the lack of strong breast-feeding outcomes/benefits, often due to weak implementation and support at the community level( 79 , Reference Taddei, Westphal and Venancio 86 – Reference Coutinho, de Lira and de Carvalho Lima 88 ). Targeted breast-feeding promotion and support by trained clinic personnel in tandem with peer-based counselling for addressing breast-feeding problems is needed. The Baby-Friendly Community Initiative expands the tenth step via combination of mother and community support groups and home visits by community health volunteers throughout the first year of life to provide support for EBF( 89 ). The success of large-scale IYCF programmes lies in the importance of IYCF counselling and community support, in tandem with community awareness( Reference Baker, Sanghvi and Hajeebhoy 90 ).

Several randomized controlled trials have demonstrated that community-led interventions, with an attention to quality, content and frequency of counselling, show positive effects on EBF( Reference Sikander, Maselko and Zafar 91 , Reference Younes, Houweling and Azad 92 ). A randomized controlled trial in Kenya found that women who received intensive home-based breast-feeding counselling addressing prevention and management of breast-feeding challenges were more likely to exclusively breast-feed than women who received semi-intensive counselling at a health facility( Reference Ochola, Labadarios and Nduati 93 ). In a cluster-randomized controlled trial carried out in Bangladesh, the implementation of participatory women’s groups led to significant increases in EBF for 6 months (15 %) and mean duration of breast-feeding (+38 d) in intervention v. control areas and pre- v. post-intervention( Reference Younes, Houweling and Azad 92 ). Similarly, in India, peer counselling through mother support groups showed improved initiation within an hour of birth, EBF and decreased prelacteal feeding at 2 and 5 years post-baseline( Reference Kushwaha, Sankar and Sankar 94 ).

The present review also underscores the importance of involvement of family members, who can influence when, what and how babies are fed( 6 , Reference Negin, Coffman and Vizintin 95 ). A study in Indonesia demonstrated that multilevel breast-feeding promotion, including individuals, families, communities and health facilities, resulted in a tenfold higher prevalence of EBF at 6 months in the intervention v. control group( Reference Sikander, Maselko and Zafar 91 ).

Strengths and limitations

The present review has a number of strengths. Inclusion of data sources in multiple languages, including French and Spanish, provided a richer analysis than conventional data sources. We also adhered closely to PRISMA guidelines, which provide a rigorous schema for data reporting. Finally, we identified gaps in the literature to inform on future research, programming and policy work.

Many studies included in the review were descriptive or observational and did not explore the associations between noted barriers and EBF. The definition of certain variables, such as inadequate maternal diet, was lacking or not described in depth. In addition, more information is needed on the quality and content of counselling given on EBF within the context of ANC and at the community level.

A major limitation is the lack of information on country-level implementation of the International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes. Mixed feeding and use of infant formula is common through actions such as free provision in maternity wards and aggressive promotion of these food products( Reference Piwoz and Huffman 96 ). Of 136 countries, only about one-third have legislation covering most or all provisions of the Code( 79 ). Effective monitoring and enforcement of national Code legislation is a key challenge, as insufficient laws and lack of sanctions allow for continued Code violations, which are compounded by the lack of political will, lack of coordination among stakeholders, continued intervention from manufacturers and distributors, insufficient data, and limited human and financial resources( 79 ). In Thailand and Cambodia, commercial promotion of breast-milk substitutes and continued provision of formula milk in hospitals continue to negatively impact EBF and contribute to high rates of prelacteal feeding among children 0–5 months of age( Reference Thepha, Marais and Bell 97 , Reference Pries, Huffman and Mengkheang 98 ). Pervasive marketing to young children continues in the face of restrictive national laws( Reference Pries, Huffman and Mengkheang 98 ).

Conclusion

To reach the World Health Assembly target of increasing the rate of EBF in the first 6 months up to at least 50 % by 2025, cultural and health systems barriers that impede EBF should be addressed. Improving knowledge and counselling skills of health workers to address breast-feeding problems and increasing community support for breast-feeding are critical to the success of IYCF programmes. Key actions are needed to support legislation and regulations on marketing of breast-milk substitutes, paid maternity leave and breast-feeding breaks for working mothers in low- and middle-income countries.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors gratefully acknowledge Sarah Straubinger for aiding with screening articles and Allison Gottwalt editing the manuscript and extraction of qualitative data from papers included in this review. Financial support: This work is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the US Agency for International Development (USAID) under the terms of the Cooperative Agreement AID-OAA-A-14-00028. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: J.A.K. formulated the research question and directed the systematic literature review. E.L. and H.D. carried out the literature review and compilation of data, with input from J.A.K. J.A.K., E.L., H.D. and C.E. jointly wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: Not applicable.