On 7 November 1903, the Italian vice-consul in Benghazi wrote to the consul in Tripoli that he had emancipated two enslaved boys, eleven and fourteen years old, respectively named Frag ben Mussa and Saad ben Mahmoud, both from Wadai.Footnote 1 Even though repressed by Ottoman laws and in decline, slavery and the slave trade were still practised in and through Mediterranean Africa at the beginning of the twentieth century.Footnote 2 It is not rare to find documents like this in the archives of the Italian vice-consular office in Benghazi; most are just declarations identifying a manumitted person as the object of the antislavery actions of a consular agent. The November report is similar to others, except for one added phrase: ‘I was able to free two enslaved boys, who asked for refuge and protection’.Footnote 3 In the second part of this line, the two enslaved boys are revealed as subjects and protagonists of the action. In fact, after their escape from the enslavers they went to the consulate to ask for manumission letters. Often hidden in Eurocentric and colonial documents, the subjectivity of enslaved persons — in this case, the two young boys — sheds light on their role in the end of slavery. Their asking for shelter and protection reveals not only their escape from enslavers but also their knowledge of how to achieve their emancipation within the legal and political framework of late Ottoman Benghazi.

Even though the caravan slave trade had declined since the mid-nineteenth century, human trafficking from Sahel regions to Libyan shores continued up to the late 1920s, during the post-Ottoman and Italian colonial era.Footnote 4 In the thriving scholarship on the end of slavery, the role of colonial and imperial powers are foregrounded in bringing about the ‘slow death’ of the social institution in Africa, including in Ottoman-controlled areas.Footnote 5 In these narratives, the abolition era in Libya started with the Ottoman firman (imperial decree) of 1857, which prohibited the African slave trade and manumitted all slaves imported into Ottoman territory in the future,Footnote 6 and was bolstered by further laws issued in 1896.Footnote 7 After the Antislavery Congress of 1890, European consular offices began intervening with local authorities to get manumission letters for enslaved persons.

Scholars like Elisabeth McMahon, Sean Hanretta, and Alice Bellagamba have provided important critiques of the triumphalist narrative of colonial abolitionism and underlined the emancipation strategies of the enslaved persons in relation to colonial regimes.Footnote 8 The slave trade in Libya has also been deeply analysed by John Wright and Ehud Toledano.Footnote 9 But emancipation strategies during the late-Ottoman and colonial period are understudied. This article aims to contribute to the scholarship on African Mediterranean slavery during the abolition period, focusing particularly on the strategies, trajectories, and solidarities of enslaved and manumitted persons in Libyan regions.Footnote 10 As stated by Toledano, the Ottoman firman of 1857 ‘marked the beginning rather than the end of an era’.Footnote 11 In the Libyan case, this era persisted throughout the colonial period.Footnote 12

It is generally understood by scholars on African Mediterranean slavery that Libyan regions played an important role in the slave trade during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.Footnote 13 Even though many researchers also agree on the importance of Benghazi in caravans and the slave trade,Footnote 14 specific analysis on the social history of slavery, its persistence in local contexts, and the dynamics of emancipation have focused more on western Libya than on the country's eastern regions.Footnote 15 The following analysis focuses mainly on the Benghazi area, using Italian records coming from consular and missionary archives. Because I am trying to overcome the Eurocentric bias of the records, awareness of the nature of these sources informs my analysis of the strategies, actions, and trajectories that did not fit the interests of European rule or the will of missionaries, consuls, and colonial officers.Footnote 16 The ‘failure’ and the ‘deception’ of the colonial archive leads me, on the contrary, to appreciate the personal and collective strategies of those individuals often considered as passive subjects of white, European, and colonial histories.

The city of Benghazi and its surroundings represent an excellent place to observe and analyse the different strategies of various actors involved in antislavery actions. One of these actors is the Italian government,Footnote 17 which played an important role in the repression of the slave trade in that area during the late-Ottoman period and after.Footnote 18 Starting from the actions of consular offices and antislavery society committees in a trans-imperial framework, this analysis argues that the individual and collective trajectories of enslaved Black persons shaped a particular geography and mobility alternative to the imperial one. Despite considering abolition and its aftermaths as top-down phenomena, the interest here is to also consider these processes through a bottom-up perspective. The article examines an understudied area, eastern Libya, that was at center of imperial rivalry, and underlines the strategies and trajectories of enslaved persons seeking to escape their vulnerable state. In their struggle for freedom, enslaved persons used and mobilised antislavery institutions to achieve their goals.

This article specifically analyses the case of the mission for manumitted Black children on the outskirts of Benghazi. Through considering some of the individual paths of these children, the research outlines emancipation trajectories, aiming also to demonstrate forms of solidarity that took place from the late Ottoman period through the 1930s. The failed project of the mission in Benghazi, as well as the shreds of evidence of a web of solidarity and of an urban organisation on the outskirts of the city, reframe the trajectories and role of enslaved Black people in emancipation beyond the intervention of Europeans. By avoiding the colonial perspective on abolitionism that emerges from Italian records, and focusing on processes initiated from below, it is possible to frame the mission within the struggles and the strategies of fugitive enslaved persons. Deconstructing the Eurocentric abolitionist narrative through a bottom-up perspective, this research contributes to an African Mediterranean history of Black emancipation trajectories.

The ‘little Moors’ of Fwayhāt

How to deal with individuals manumitted through its actions represented one the main issues for consular officials in Ottoman Libya. These European authorities often tried to keep the freed persons under informal protection. For older formerly-enslaved persons, consular offices granted several days of accommodation before sending the individuals off to fend for themselves. These persons frequently fell into distress: ‘given the lack of employment in Benghazi, they either fall back into slavery or indulge in idleness and uncertain and occasional work, sometimes allying themselves with the worst elements of the country’.Footnote 19 In 1908, Friar Lickens, a local agent of the Italian Antislavery Society (IAS), put several manumitted Black children into the custody of Christian families in Benghazi.Footnote 20 The difference between domestic slavery and custody in households was often a subtle one. Lickens acted alone, without consular, IAS, or Catholic approval. The poor conditions the children lived in and the risk of provoking the Ottoman administration pushed the Italian consular agent to order him to stop this action of ‘keeping, for about two years, not only boys and girls always closed in, but also forced to speak in a low voice to not make their existence known! the poor creatures are almost getting crazy’.Footnote 21 This order was also issued by the religious authority, the apostolic prefect, who ‘ordered the Belgian layman to deliver to the Italian Agricultural Institute the MorettiFootnote 22 purchased by him and whose indefinite stay in private homes was not only a danger to the mission but was even worse than slavery’.Footnote 23

The Italian Agricultural Institute, known also as Fwayhāt Mission, was a Catholic institute dedicated to Black manumitted children, founded in 1904 on the outskirts of Benghazi, in a locality called (al-)Fwayhāt (الفوايهات ).Footnote 24 Under Italian consular protection, supported and funded by the IAS, Propaganda Fide, and the National Association for Italian Missionaries,Footnote 25 the institute in Fwayhāt was a mission of the Congregation of Saint Joseph and it became an important player in the antislavery actions in the Benghazi region.Footnote 26 After several visits and negotiations in 1902 and 1903, Father Girolamo Apolloni founded the mission in 1904, and it became fully operational in 1905. During its mission, the Fwayhāt institute hosted dozens of young Black formerly enslaved children, teaching them the Italian language, Catholic catechism, and handcrafting.Footnote 27 A female section was established and managed by the Sisters of Charity of Immaculate Conception.Footnote 28

The manumitted children hosted in the Fwayhāt institute were referred to in the Italian sources as Moretti (‘little Moors’).Footnote 29 As an Italian term used to designate all Black children, it was used by the missionaries in Fwayhāt specifically for the children hosted in the mission. This was a racial category used to define all the young enslaved or manumitted persons coming from different regions of the Sahel (and mainly from Wadai, Bornu, and Baghirmi). Notwithstanding their diverse geographic, social, or ethnic origins, in Fwayhāt all the children became ‘Moretti’.

In the Italian as well as the Catholic strategic visions, these Moretti were expected to play an important role in the spreading of a European-Christian imperial project in Africa. The mission officially succoured young manumitted Black children in its workhouse,Footnote 30 but this was, in reality, a means to the larger ends of converting souls and creating of a community of Black Italian-speaking Christians in Ottoman Benghazi.Footnote 31 Catholic proselytism and the imprudence of Father Apolloni drew the hostility of the local Muslim population towards ‘this our institute, that is already unpopular in Benghazi’.Footnote 32 In the attempted evangelisation of Black children, the case of the young and promising Bisciara reveals the missionaries’ hopes, projects, and failures.

Born in 1893 in Wadai, Bisciara was among the first manumitted children hosted in the Fwayhāt mission, arriving in March 1905.Footnote 33 In the following years, Bisciara (christened ‘Giuseppe’ Bisciara by the fathers) learned Italian quite rapidly and embraced Catholicism. To foster Bisciara's abilities and inclinations, the mission sent him for a short visit to the motherhouse of the Saint Joseph Congregation in Turin in 1906 or early 1907.Footnote 34 After his return to Benghazi, Bisciara repeatedly expressed his wish to return to Italy, to become Christian, and to join the Saint Joseph Congregation.Footnote 35 His desires were fulfilled in May 1909 when he returned to Italy and stayed for more than three years. The congregation sources are surprisingly silent about Bisciara's long stay, except for a file with an interview conducted before he entered the novitiate in September 1909, conducted to evaluate his knowledge and faith and interrogate whether he had a ‘mark of infamy’, criminal convictions, illness, or disability. Bisciaria's case notes read, ‘No. He belongs to the Hamitic race and [is] therefore black in complexion’.Footnote 36

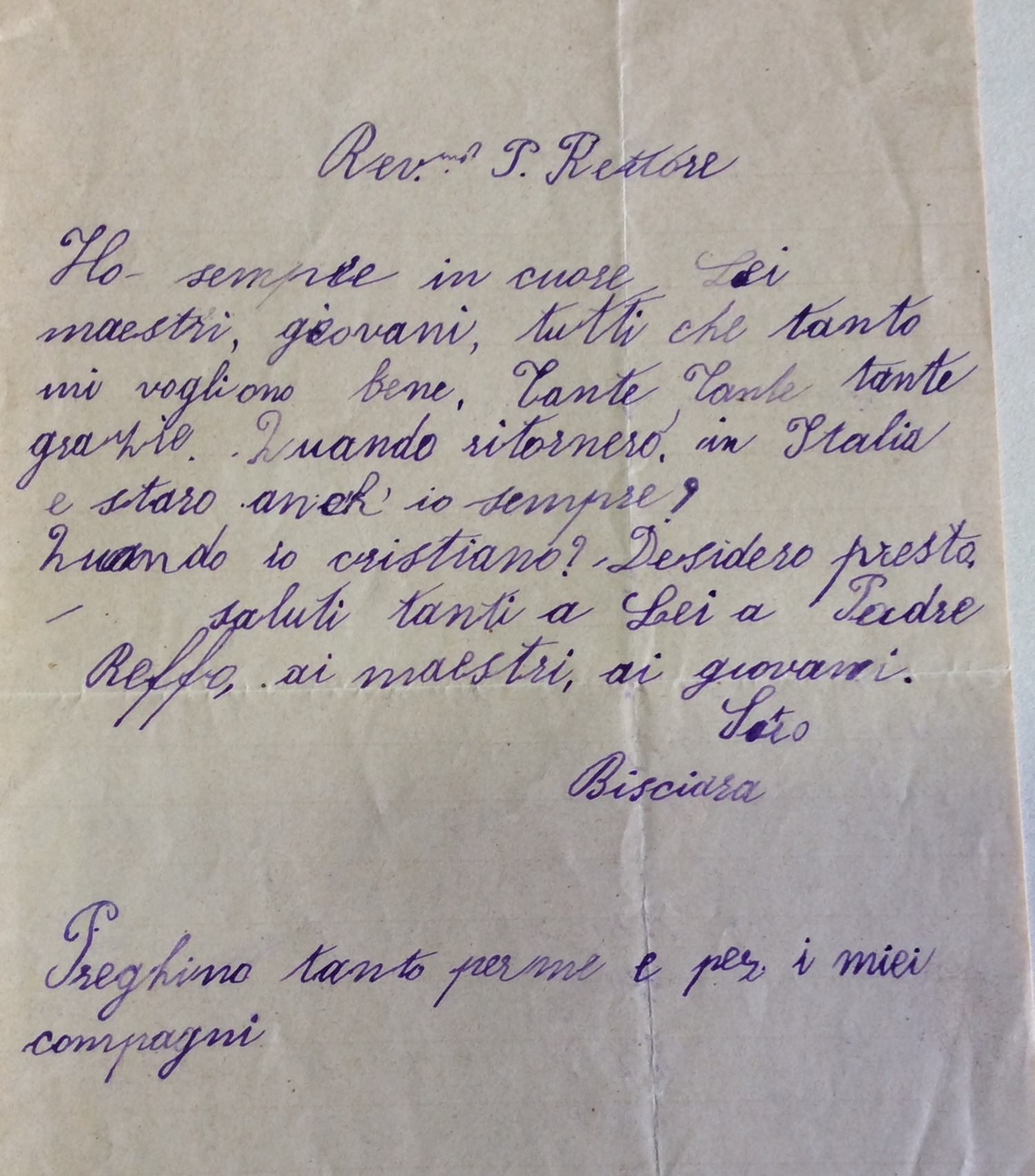

Fig. 1. Letter of Bisciara: ‘Most reverend Father Rector, I always care about you, the teachers, the youths, and all those who love me so much. Many, many thanks. When I will return to Italy and will always stay too? When I [will be] Christian? Hope soon. Many greetings to you, to Father Raffo, to the teachers, to the youths. Yours, Bisciara. Pray a lot for me and for my friends’.

Source: ACG, 5.2 Comunità e Opere, 2.4 corrispondenza Girolamo Apolloni a Padre Giulio Constantino, n.d. (1907?).

Although the congregation's records are largely silent on Bisciara's Italian experience, the reports from Benghazi reveal its great impact on the mission. Bisciara's departure from Benghazi in September 1909 excited the other children of the Fwayhāt institute. One year after he left, in 1910, six Moretti were sent to Italy from Fwayhāt. Ironically, the control and restriction on the mobility of Black passengers — which the IAS and antislavery agents promoted, accusing Ottomans of tolerating human trafficking — became the biggest problem for the missionaries:

The first three, Mussa, Idris, and Abdallah, [were] accompanied by Brother Costa Maurizio. But what and how many difficulties it took to embark them! […] Since last year, rumours have spread in Benghazi that we had embarked many Moors […] so that extraordinary surveillance began and is still being carried out at the port so that blacks do not leave without a passport; then the passport is not given to those who request it, and so if they want to leave they have to do it by smuggling, and smuggling a Moor in broad daylight is all the more difficult as it is necessary to act in such a way as not to compromise our Institute. How did it happen this time? The three young people dressed up as ragmen and sent to accompany horses to the steamer […] Two weeks after their departure from Benghazi, Fr. Gerolamo left with three other Moors, named Abdellai, Said and Saad […] fortunately peasants and Moors from Misrata, who had come to Benghazi to cut the barley, left with that boat; our three Moors mingled with the same ones; but not without serious difficulties so that one of them had to be pulled aboard with a rope from the rear side of the ship.Footnote 37

Perhaps heightened by the departure of the Moretti, by the open evangelisation of the fathers, or by the new political situation in the Ottoman Empire, hostility towards the mission became increasingly problematic in Benghazi.Footnote 38 A father of the congregation wrote to the housemother's superiors the disappointment to be still under the Ottoman rule hoping the Italian one in the region.Footnote 39 Considering the situation, one director of the institute proposed to move the mission to Scicli, in southern Sicily.Footnote 40 However, the Italian consul refused this proposal, citing his reasons concerning the health risks experienced by Black people transferred to ‘a country of white people’.Footnote 41 The mortality of Moretti was already high in the Libyan mission and in northern Italy their condition of health worsened. Like other cases of Moretti sent to Europe during the nineteenth century,Footnote 42 those from Benghazi to Italy experienced illness and death often related to bronchitis. Out of seven Moretti sent to Piedmont, three died from health complications in 1911.Footnote 43

The journey of Moretti to Italy and the attempt to create a Black local clergy within Saint Joseph Congregation should have sealed the mission's success, but in reality, sent it into crisis. The Moretti who went to Italy did not have great success in their religious training. Father Apolloni wrote: ‘Said and Saad, quite cheerful but lunatic. Abdellai remains, who would like to enter the novitiate but it does not seem that Fr Rejneri is very happy. Fr Achille continues to protest that it would be better to send them back to Benghazi'.Footnote 44 Even the most promising, Bisciara, left the novitiate at the end of 1910 and moved to a workhouse belonging to the congregation to train as a carpenter. By late 1911, Bisciara expressed his wish to return to Benghazi.Footnote 45 On 22 December 1912, two months after the signing of the treaty that ended the Italo-Turkish War, and more than three years since his departure, he travelled from Syracuse to Benghazi.Footnote 46 The other three Moretti from the mission living in Piedmont — Said, Saad, and Abdellei — also returned to Benghazi around the same time. Even though their religious careers did not succeed, their training and formation, at Fwayhāt and in Turin, proved useful in a Benghazi occupied by the Italian army.

The introduction of Italian colonial rule reshaped the local society, creating new power relations within the country and, consequently, groups who had been a minority or marginalised during the former rule could take advantage of the new conditions.

‘The desire of the Moors to leave’

The Italian occupation brought destruction and uncertainty to Libyan society, as well as to Fwayhāt mission. When the war broke out, in September 1911,Footnote 47 the fathers evacuated the mission and were hosted in Benghazi in a Franciscan convent, leaving the Moretti behind.Footnote 48 Local Libyan Bedouins destroyed the mission's buildings and re-enslaved some of the Moretti. During the war, with the slow advance of the Italian army, Fwayhāt became for months a military frontier dividing an occupied zone from strongholds of local Ottoman resistance.Footnote 49 The warfare reframed not only the mission and its activities but also, and above all, the remaining Moretti and their opportunities. Young, local, Christian, Italian-speaking, and educated according to the occupiers’ ideals of civilisation, the Moretti could play a useful role for the Italian colonial enterprise. The beginning of Italian occupation started the decline of mission, due to the new social and economic conditions of the emerging colonial society:

The lads run away from us and we no longer know how to keep them in; they are reduced to twenty and if they could and let themselves go they would all go away (maybe except two). The captain of the carabinieri scolded them saying that they should not leave us but who knows if it will help… all Italians are looking for and want these little blacks… they give them money and good food.Footnote 50

While some Moretti were employed in domestic work by Italian civilians, even more job opportunities were found in the army.Footnote 51 In 1912, Said, Saad, and Abdellei (baptised as Pancrazio) came back from Italy and were rapidly recruited into the colonial troops, thanks especially to their skills in Italian and local languages, knowledge of Italian and local customs, and familiarity with the Benghazi area.Footnote 52 Although the mission failed to launch religious careers, it did an excellent job training future soldiers. By 1913, former residents of the Fwayhāt mission were almost all soldiers among the Italian colonial troops.Footnote 53 Moretti were viewed by the Italian invaders as a friendly local element, useful for facilitating their occupation of the region. The rapidity and the ease of recruitment of Moretti for the colonial troops contrasted with the initial hesitation of Italian commanding officers about the deployment of other Ascari (African soldiers of the Italian Army) in the Libyan battlefield.Footnote 54

Those Moretti recruited into the army leveraged their backgrounds to improve their lot within the Italian colonial project. Even though recruited into the colonial troops of the Ascari alongside mainly Eritrean soldiers, the Moretti had a different background, training, and education.Footnote 55 For instance, Abdellei Pancrazio, recruited by the colonial troops immediately after his return from Italy, had to dress in the colonial uniform that forced soldiers to walk and march barefoot. The imposition of the Eritrean Ascari custom to go barefoot did not suit Abdellei Pancrazio.Footnote 56 Not being used to this, he stayed for a long time in the hospital because of the injuries to his feet and then asked to be excused from military service.Footnote 57 But despite refusing these orders, he continued his job with the army as an interpreter,Footnote 58 revealing how precious his cultural and linguistic knowledge was considered by the military administration.

The Moretti could use the skills gained at the mission to advance in the newly emerging society beyond the boundaries imposed by the religious fathers, who complained of ‘the desire of the Moors to leave – for the money that is easily recovered – for the requests – for freedom – entertainment’.Footnote 59 In 1913 the fathers considered closing the mission because of the ongoing warfare and their disappointment with the choices and life trajectories of so many former mission residents.Footnote 60 The fathers had previously sought to keep the grown Moretti close to the mission through a family bond within a Catholic framework. One of the strategic aims of the Saint Joseph Congregation was, from the beginning, the creation a village of Christian Black families attached to the mission. Because the mission had targeted Black enslaved children, the issue of marriages emerged only a number of years after the beginning of its activity. Yet by 1912 the situation had become quite urgent, with one of the fathers of Fwayhāt mission writing: ‘One thing, however, begins to annoy us and it is that these Christian boys of ours, soldiers and not, want to take a wife and the dilemma is to find them for everyone’.Footnote 61 The fathers had to act quickly if they did not want to see the collapse of their project.

The Moretti's desire for sexual relations jeopardised the religious and sexual normative boundaries that structured the colonial system. In 1913, Marcelo, a Moretto who had enrolled in the army, had sexual intercourse with a Black Muslim woman, breaking the fathers’ requirement that he take a Moretta — that is, a Black Christian woman — as a wife. According to Father Pagliani, this occurred because of the lack of available women in the Moretti group. The religious prohibition became a military imposition and Marcelo was severely punished with several days in the pillory.Footnote 62 Despite efforts to control and manage the private and sexual lives of the Moretti, numerous residents crossed the moral and sexual boundaries built up by the religious mission:

Fargialla and Girolamo had left the military … Here they lived badly full of pretensions and lazy, and it gets worse: together with Said and Bisciara dishonestly had affairs, the husbands with the wives of the others and also the wives with each other, all without exception … And they weren't even ashamed to admit it. The fact that Said – graduated zaptié – and Bisciara go to the casinos, however, we know from them. From others, we know that Giannina who is at the Berca and the other women who are now in the city lend themselves to satisfying other men while their husbands are at the field or the service.Footnote 63

The desire to escape the strictures of the mission can also be seen in the estrangement of Bisciara, once considered the most promising pupil, from the fathers. Having abandoned his religious career, Bisciara worked as a carpenter upon his return to Benghazi. The letters and postcards of young Bisciara (sent between 1908 and 1911) asking to go to Italy and to become a priest reveal a specific moment in his personal formation. In the same terms, the estrangement of Bisciara from the mission attests to his eventual autonomy from the schemes and paths programmed for him.

The Moretti, raised and educated by the mission, did not fulfil the expectations of the fathers. At least, not all of them: ‘Apart from the dead who they alone give us consolation, otherwise of the living who have left the Mission not even one lives according to the education and teaching they have had. Not even one lives as a good Christian. Everyone lives an immoral and dishonest life’.Footnote 64 The sad comment of Father Airale about the former residents, regarding them as far from the moral education given to them by the Catholic mission, sheds light on the personal and collective agencies of these individuals. Their desires and personalities emerge alongside the different antislavery institutional projects and actors (including consulates and missionaries). The detachment of Bisciara from the mission and the placement of Abdellei Pancrazio within the army show two different strategies for achieving personal autonomy and individual fulfilment.

A web of solidarity

The community-making of the Moretti in the mission created a space of connection and shared experiences and knowledge, not only among them, but also with the fathers that taught them the Italian language. In turn, the fathers learned a new geography beyond their Eurocentric knowledge. In 1907, some years after the beginning of the mission's activities, Father Airale asked the Moretti to tell him their stories of enslavement and of their journeys. Thanks to these stories he reconsidered the Saharan space, its peoples, its distances, and the complexity of its environment, stating in his report that ‘the idea that we have in Europe of the great desert is wrong’.Footnote 65 It seems that the rich and detailed description of the countries, peoples, and customs the Moretti had seen during the trans-Saharan crossing widened the fathers’ understanding. Moreover, some of the fathers learned Libyan ArabicFootnote 66 in order to be able to have basic conversations — although for complex discussions or concepts, a Moretto translated from Italian: ‘In the evening the Father would say a few words to them in Arabic so that they could also understand the new ones. He says the slightly more difficult sentences in Italian and for the most part, Mussa then translates them with ease into his own language’.Footnote 67

Although a great part of the Moretti came from the Wadai region, like Bisciara, others like Mussa came from Kukawa, the capital of Bornu, or from Banda region, Bagirmi, and so on. This meant that the Moretti spoke a variety of languages. The archival sources don't detail the language or pidgin used as a lingua franca at the mission. But the fact that Father Girolamo Apolloni, the subject of the above quote, was fluent enough to be able to preach in the local Arabic by 1909, only one year later, and the reference in the source to ‘his own language’ suggest that the language was not Libyan Arabic.Footnote 68 It is possible that the common experience of trans-Saharan crossing and periods of enslavement, as well as post-emancipation life in Benghazi and the mission gave rise to a shared lingua franca amongst the Moretti at the mission.

Evidence of an information sharing network among the enslaved people in the Benghazi region is demonstrated by the case of the 13-year-old Imar, who escaped from slavers in the Libyan hinterland and was helped by unknown Black persons to reach Benghazi and the Fwayhāt mission in 1909. An unknown Black person informed Imar about how to pursue manumission and about the existence of the mission. Knowing this information, the boy ran away and reached Benghazi after ten days of walking. Fearing re-enslavement, he hid in some gardens trusting no one until he found another Black person, an old Muslim man, to ask for help. The boy told his story and the old Black Muslim ‘moved with compassion’ accompanied the young Imar to the Catholic mission. The action of the old man surprised the fathers, who wrote in a report ‘this is an exceptional and strange thing for a Muslim’.Footnote 69

The informal web of solidarity in this case took the form of a suggestion, passed by word-of-mouth to an adolescent boy, of how to pursue emancipation. Imar's vulnerability as a young runaway in a foreign land shaped his decisions about who to ask for help during his escape: the boy viewed Black people as less likely to betray him, perceiving a sense a shared social subalternity. While other factors (like the proximity to Fwayhāt and the sympathetic inclination of two random persons) certainly played a role in his emancipation, Imar's perception of Black solidarity was, in his case at least, vindicated: two unknown Black persons, in different moments and places, helped the young Imar to get his manumission.

Evidence of the solidarity of enslaved people, moreover, predates the mission, and played an important role in mobilising the IAS network and consulates to abolition. In 1904, the Italian Minister of Foreign Affairs, informed by the IAS board, wrote to the Consul in Tripoli that two enslaved women, named Fatima and Hdiga, escaped with other enslaved Black persons from Zliten and fled to Homs. Zeid el Mal, their companion, did not manage to escape and she remained in slavery. Fatima and Hdiga claimed the liberation of Zeid el Mal and were helped by other enslaved or former enslaved Blacks, especially by Bubakar who accompanied them to Tripoli to involve the British and the Italian consulates in the matter. Thanks to this action, the diplomatic pressure of the consulates obliged the Pasha of Tripoli to investigate this issue concerning slavery.Footnote 70 The mobilisation of the IAS, Italian, and British consular authorities widened the possibilities for manumission, by enabling liberated people to seek freedom for companions still in bondage. The existence of informal solidarity in Libya among Black enslaved persons is confirmed by the implication of Bubakar and others who helped the women and testified that Zeid el Mal was kept in slavery:

Despite the fear of the Negroes of meddling in such affairs, some of them, among whom their chief, have deposed that the Zeid el Mal is kept hidden in chain by the master, and that money has been offered to the Negroes to bribe them and that one named Bubakar who refused to persuade the fugitives to return to their master was then falsely accused by a relative of Sinusi Bin Hag Mohamed Mahgiub and imprisoned. After his release, Sinusi and his accomplices told him ‘now the Consul of Homs protects you, but we are capable of beating him, as we have beaten another Consul’ thus trying to intimidate the blacks so that they do not speak or lay the false.Footnote 71

Zeid el Mal was liberated in the end, thanks to the actions of Fatima, Hdiga, Bubakar, and others who mobilised different institutional actors to their cause. Social conditions informed these actions of solidarity: even though enslaved persons came from different regions, in the Libyan context they were racialised as ‘Blacks’ and categorised socially as ‘slaves’. Opportunities arose to help one another to alleviate a shared marginalisation.

Slavery is a homogenising category that hides a wide range of variation. Following the analysis of Toledano on the necessity of understanding slavery in Ottoman areas more as a ‘continuum of various degrees of bondage rather than as a dichotomy between slave and free’,Footnote 72 it is important to focus on its racialising effects. Even though colonial and Eurocentric documents represent ‘slavery’ and ‘blackness’ as overlapping categories in Libya, the variety of conditions of enslaved or formerly enslaved Black people differed, as did the racialised perception of blackness. Similar to the Moroccan case, in Libya ‘slavery was associated with blackness',Footnote 73 but both were also contested categories. Lineage, gender, age, religion, geographical origin, and skin colour played a major role in the enslavement as well as in the emancipation process, destabilizing any monolithic understanding of Black slavery.Footnote 74 In addition, sexual relationships between male masters and female enslaved persons were common and the acknowledgement of the offspring could generate ‘black’ or ‘dark-skinned’ heirs in notable familiesFootnote 75. Nevertheless, discriminatory views about blackness as a ‘stigma of ex-slave’Footnote 76 — that is, a sociocultural construction based only partially in phenotypic features and involving lineage, history, religion, and customs — influenced the life trajectories of Black Libyans into the postcolonial era.Footnote 77 The complexities and variations within the categories of ‘Black’ and ‘slave’ did not negate social and racial discrimination towards enslaved or formerly enslaved people.

Acts of solidarity amongst enslaved Black persons facilitated mobility, enabling escape to places where they could live as free people — or, at least, freer people. Building on the insights of David Featherstone, the cases mentioned above confirm ‘the importance of marginal groups in shaping practices of solidarity’, challenging ‘the assumptions that subaltern groups, those subject to diverse forms of oppression, lack the capacity or interest to construct solidarities’.Footnote 78

Little Wadai: a Black heterotopia

Consulates, the IAS, and missions could be useful tools in the struggle to acquire vital documents like letters of manumission, legal support, and shelter. In individual and collective struggles for emancipation, formerly enslaved people not only created alternative forms of mobility through which they enacted their solidarity, but also alternative urban spaces. The Fwayhāt mission hosted several Moretti but was organised, planned, and managed by the Italian fathers. Beyond the Moretti of Fwayhāt and Black persons still living under conditions of slavery — in households or in agricultural fields — there was a third group of Black formerly enslaved people in Benghazi.Footnote 79 Built after the first manumissions, in 1857, a community known as Little Wadai or the Sudanese Village was located at As-Sabri, close to the old city on the eastern shore.Footnote 80 A neighbourhood comprised largely of enslaved or formerly enslaved Black persons was hardly unique in North Africa, as Ismael Montana and John Hunwick have detailed in their works on the bori ‘colonies’ in Mediterranean Islamic urban areasFootnote 81. The ‘Sudanese Village’ in Tripoli lasted from 1877 until at least 1909 and in Benghazi until the early 1930s.Footnote 82

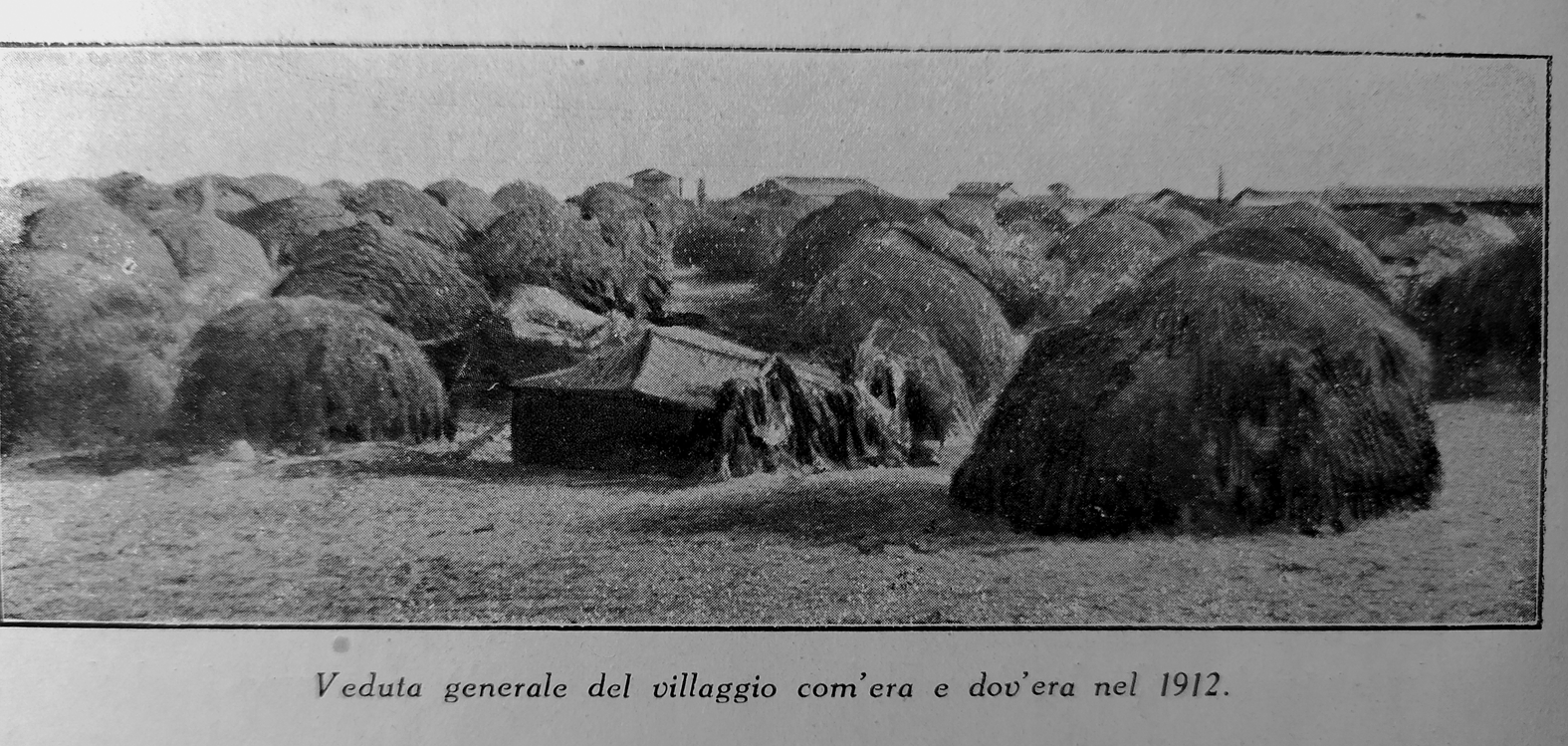

The boundaries between the three groups of Black people of Benghazi (Fwayhāt, Old City, As-Sabri) were porous. For instance, some of the grown Moretti left the Fwayhāt mission and went to As-Sabri.Footnote 83 The inhabitants of Little Wadai were employed daily in the saltworks, one of the main commercial activities of Benghazi, as well as in seasonal works,Footnote 84 strengthening their commercial and social connection with the Old City.Footnote 85 The ethnic specificity of Little Wadai was revealed also in its urban structure, in its separation from the rest of the city, as well as in the architecture of its houses, closer to the Central African tukul (circular structures, often with conical roofs: see Fig. 2, below).Footnote 86

Fig. 2. Little Wadai/Sudanese Village ‘Overview of the village as it was and where it was in 1912’.

Source: U. Tegani, Bengasi: uno studio coloniale (Milan, 1920), 140.

A French journalist in 1912 crossed the palm grove of As-Sabri, ‘near which stand many branch huts, which suddenly transport us to the heart of the Sudanese country’, and gave a description of the regional composition of the inhabitants: ‘almost all from Bornou, Wadai and regions bordering Lake Chad’.Footnote 87 The journalist assessed that the inhabitants of the palm grove neighbourhood numbered approximately 20,000, clearly making a mistake — or a typographical error — considering that she later stated that the total population of Benghazi was 25,000.Footnote 88

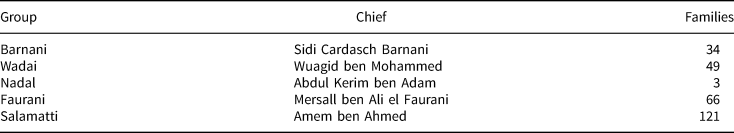

While the French report published in 1913 refers to the Ottoman period, the publication of an Italian journalist, Ulderico Tegani, gives us more details on Little Wadai after the colonial occupation. A census done by the Benghazi municipality (or ‘Beladìa’ in the Italian transliteration of the Arabic term) at the end of 1913, assessed that the ‘Sudanese’ people of Little Wadai numbered 952, identified according to the groups included in Table 1.

Table 1. Census of Little Wadai by Benghazi Municipality, 1913.

Source: Tegani, Bengasi, 123.

Beyond the inhabitants of Little Wadai, the journalist declared the existence of a Black population still enslaved within the households of the city: ‘then there was news of another 5-600 Negroes scattered as slaves to notable and wealthy Arab families of the city’.Footnote 89 Not surprisingly, the previous Italian abolitionist initiative aimed more at undermining Ottoman rule and justifying colonial invasion than at a real humanitarian purpose. In fact, as stated by Tegani's report, forms of slavery continued even during Italian colonial rule, a common practice in European colonial empires analysed by several scholars.Footnote 90

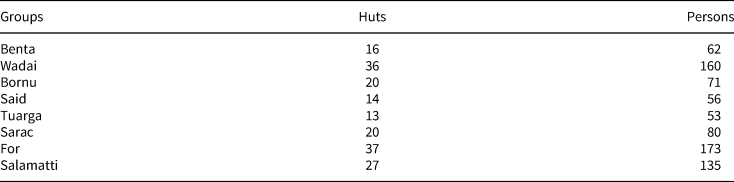

It is noteworthy to consider the differences between the numbers, categories, and group-identifications of Beladia (in Table 1, above) and those in the Italian medical census made in 1914 when faced with an outbreak of plague (below, in Table 2).

Table 2. Medical census of Little Wadai, 1914.

Source: Tegani, Bengasi, 125.

The medical census assessed the total number of inhabitants of Little Wadai at 790 (and the total number of inhabitants of Benghazi at 21,292), indicating the number of huts in order to be able to control the infected ones.Footnote 91 The names of the ‘Chiefs’, which could reveal Little Wadai as a confederal system with a hierarchical structure, were not identified in the medical census. While some groups were the same as in the previous census, others emerged in the new list. It seems that the group identifications mainly followed the regional origins of the inhabitants (Wadai, Bornu, Salamat) or ethnic ones (For, Tuarga, Benta).Footnote 92

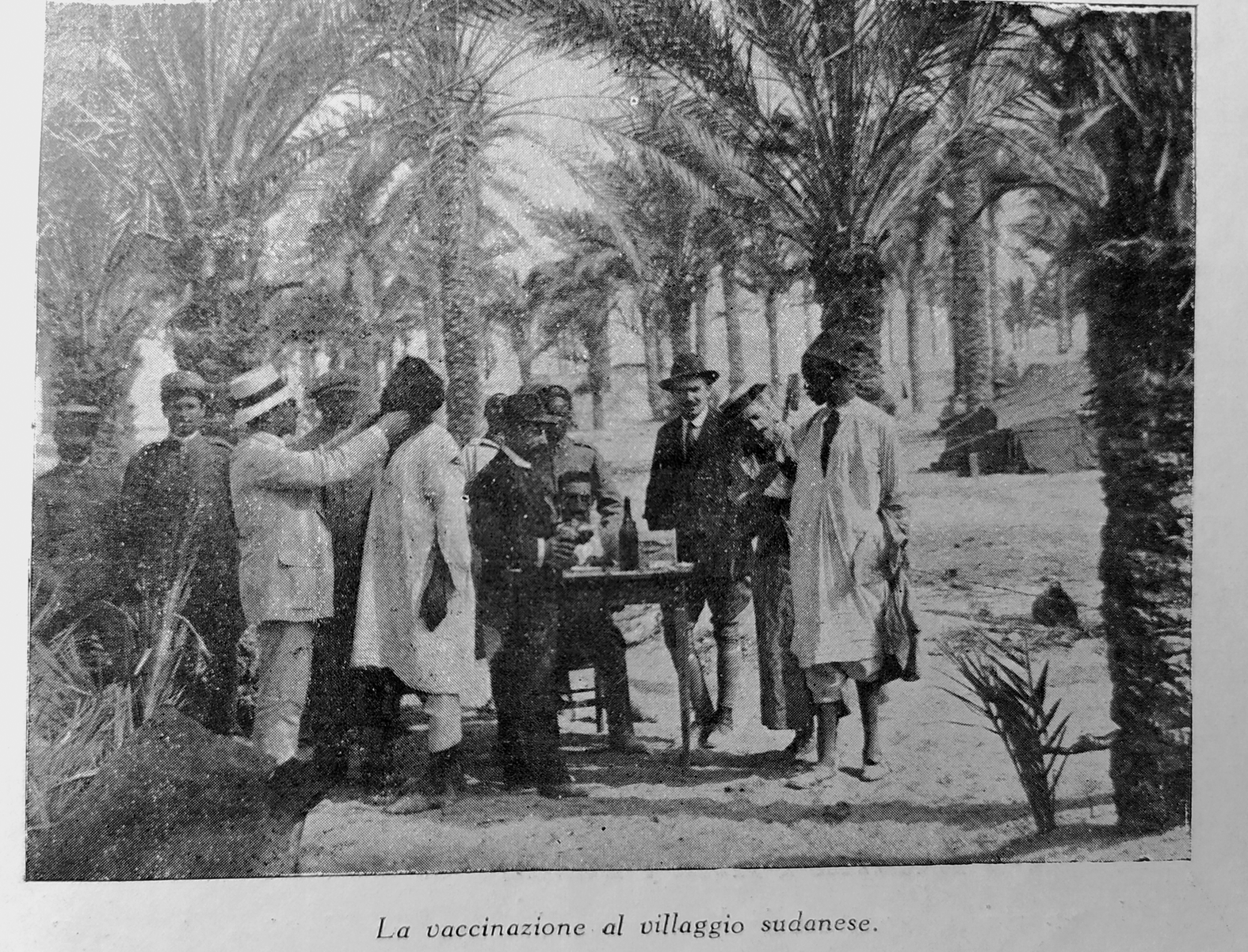

Little Wadai was marginalized both socially and in terms of infrastructure. It had no public services and no sewer drainage, so the hygienic conditions were already poor when, in the last months of 1913, the plague began to hit Benghazi. The colonial administration wanted to avoid a hotspot in Little Wadai at all costs. The director of the Health Office, Vincenzo Mercatelli, opted for a drastic solution. He ordered Little Wadai burned and its population transferred elsewhere for mass vaccination: ‘the village made up of huts of minimal value was then set on fire, the Sudanese were awaited in a neighbouring land, they were isolated, after which the cases of plague ceased. Health returned among those people who thanked the Italian Government’.Footnote 93 The report issued by the Italian Ministry of Colonies completely hides the reactions to this destruction, which we can imagine greatly affected the inhabitants. In Tegani's report, the same dramatic moment of the destruction of Little Wadai is described with some sorrow from the inhabitants: ‘amidst the comment of not a few tears, the dirty old tukul fell to ashes, raising a formidable column of smoke. The fire, which was spectacular, took place on February 12, 1914, and the Blacks were immediately vaccinated’.Footnote 94

Fig 3. ‘Vaccination at Sudanese Village’

Source: Tegani, Bengasi, 181.

The 1914 destruction did not put an end to Little Wadai. In fact, in January 1915 the Official Bulletin of Cyrenaica published a decree (issued in November 1914) concerning public works for ‘the building of the new Sudanese Village’.Footnote 95 Curiously, the construction of the new village, even though under colonial administration and planning, followed ancient urban forms. Little Wadai attracted the attention of the anthropologist Nello Puccioni, who came to Cyrenaica in January 1928 also to study its population. In his diary, he described the village as ‘consisting of huts made with all systems, wood, old oil cans etc. Only a few are made of palm leaves as they should originally be’.Footnote 96 So, in 1928, Little Wadai and its houses looked much like they had before the great burn of 1914.

Puccioni wrote of his first trip to the community that he visited the hut of the ‘chief of Wadai’, named Marsal El Haida. In a second visit, in March 1929, Puccioni met another chief of the village, Salabi (sometimes spelled also Sallabbi), who approved and prepared the people for the anthropological study.Footnote 97 The negotiation for this visit to Little Wadai suggests a form of autonomy of this specific urban space that was represented, and represented itself, as something different and detached from Benghazi, not just as its periphery. This partial autonomy could be seen in the official nomination of a chief of the village: ‘Sallabbi’, who is defined by Puccioni as ‘chief of the camp appointed by Benghazi municipality’.Footnote 98 Sallabbi gave to Puccioni, during his first visit, a demographic census of the village that stated a total of 519 inhabitants, divided into different groups (Uadai 82, For 49, Saràua 34, Baghirmi 86, Banda 38, Salamat 67, Bornu 43, Dagiu 70, Rascièt 50).Footnote 99

Sallabbi not only organised the visit but acted also as a mediator for the anthropologist, explaining to him that in the village there were two main groups of mutually understandable dialects, one composed by Salamat, Dagiu, and Rascièt groups, the other by Saràua and Baghirmi. The other four groups in the village spoke different dialects without any linguistic affinity with each other.Footnote 100

Little Wadai, whose urban life was thriving at least until 1930, had its autonomy and complexity: ‘the Sudanese Village is a real Village that has its streets, its crossroads, its squares’.Footnote 101 The village became quite known for its dances. The French report of 1912 mentioned above notes, ‘Every Friday, there is a festival in the village. To the sound of tam-tam, darboukas, high-pitched flutes, bizarre instruments, swollen, ornate skins, amulets and pearls, the negroes perform the “Sudanese dance”’.Footnote 102 Even though there is no detailed description of this dance, or analysis of its social and cultural role, it is possible to frame it within the widespread phenomenon of bori ceremonies among North African Black communities. Thanks to the anthropological study of Arthur John Tremearne on demon-dancing in West and North Africa we know that bori ceremonies were practiced in Tripoli until 1914.Footnote 103 Sixteen years after the French report, an Italian anthropologist, Nello Puccioni watched a dance celebration, but it happened on Sunday and not on Friday, and was organised by the colonial administration for the anthropologist with ‘the Commissioner who had invited some ladies… ask[ing] them not to deviate into incorrect dances’.Footnote 104

According to Puccioni's description, the federative composition of Little Wadai also informed the community's cultural expressions. The creation of a federative urban space and the inhabitants’ maintenance of their cultural and linguistic traditions embodied the rejection of enslavement as the totalising experience of their lives. Although brutal and traumatic, enslavement did not negate who they were before. It is not clear, at the present state of the research, what kind of interactions occurred between the different chiefs described by Tegani in 1920, and whether the ‘chief of the village’ appointed by the municipality like Sallabi was elected or nominated by the village. Nevertheless, these documents offer new perspectives on Black emancipation trajectories on Libyan shores. The Blacks of Little Wadai reformed their groups, their cultures, and a federative political system claiming in this way a form of autonomy, even though socially marginalised.Footnote 105

The case of Little Wadai demonstrates the autonomous organisation of a part of the former enslaved Black population. It differs from the experience of the Fwayhāt mission, in which the main direction and management came from the Italian missionaries even though, as we have seen, some divergences from the established paths occurred in the lives of the Moretti. While in the Fwayhāt mission all the Black children became Moretti for the fathers, who omitted the regional or ethnic origins of their guests, in Little Wadai the origins of the inhabitants, formerly enslaved persons, were claimed and structured the social system of that urban space. ‘Moretti’ was a homogenising and imposed category in the hierarchical system of the mission, as opposed to what occurred in Little Wadai with a federation of the different groups. Little Wadai created a specific form of an African village reflecting its different components.

Even though the social and economic relations tightly linked Little Wadai to Benghazi Old City, access to this urban space for foreign (white) visitors was mediated and prepared by the inhabitants through their representative. More than an ethnic neighbourhood but less than a city, Little Wadai was at the same time the product of discrimination and the outcome of an autonomous organisation that took place after the segregation and in the margins of the ruling society. Considering its relationship of conflict and dependency with the city, Little Wadai could be framed as a Black heterotopia, a counter-space that reflected and challenged the power relations of Benghazi.Footnote 106 Avoiding romanticisation, this analysis argues that these forms of autonomy, as well as of solidarity, took place more as an original result of segregation and discriminatory policies than as a form of structured political resistance.

Conclusion

Highlighting the individual and collective actions of Black enslaved people and their struggle for emancipation, this article argues for the existence of an informal web of solidarity that helped Black enslaved persons throughout Libya pursue freedom. At the present state of research on this topic, we cannot assess if this web of solidarity was structured and organised like an African Mediterranean version of the North American underground railroad.Footnote 107 But the circulation of information about how to get manumission letters demonstrates the existence of at least an informal network of solidarity. The scattered sources and the reticence of the consular records on the role of the enslaved persons in most of the manumission acts do not allow for defining the precise nature and dynamics of self-help and solidarity. Nevertheless, the cases of Saad Ben Mohammed and Frag Ben Musa, Zeid el Mal, and Imar reveal a bottom-up process of emancipation involving more than individual runaways, thereby complicating prevailing narratives of abolitionism and Black emancipation in Libya. This article reveals how the pursuit of freedom by individuals interfaced with and informed the collective mobilisation of different institutional actors, like the IAS, consulates, and missionaries to obtain manumission and social advancement. Black solidarity also found expression in processes of self-configuration in understudied diasporic spaces such as Little Wadai. Born after the Ottoman firman of 1857 and still existing in the 1930s, the community wrested a share of autonomy on the outskirts of both the city and society. In these margins, Black former enslaved groups created a space of a negotiated self-autonomy, with their customs and political forms. Little Wadai and the Sudanese Village in As-Sabri constituted an important node in the diasporic Black web that encompassed Central African regions and the Mediterranean areas.

Descendants from this diaspora today comprise a North African Black minority that still today faces racial discrimination, especially in post-revolutionary Libya.Footnote 108 Imperial borders and repression of mobility, moreover, remain important factors in the persistence and emergence of new forms of slavery in Libya. Nevertheless, mobility networks, sometimes fueled by solidarity but more often exploited by criminality, pursue greater social and economic opportunities thereby challenging imperial borders transcribed as postcolonial frontiers.Footnote 109

Acknowledgement

This article has received funding from the European Research Council under the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (SlaveVoices, Grant Agreement ID: 819353).