Book contents

- Carpe Diem

- Cambridge Classical Studies

- Carpe Diem

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures

- Acknowledgements

- A Note on Ancient Texts and Translations

- Abbreviations

- Introduction In Search of Present Time

- 1 The Archaeology of Carpe Diem

- 2 A Moveable Feast

- 3 Gathering Leaves

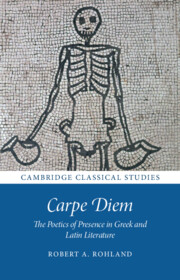

- 4 The Pleasure of Images

- 5 As Is the Generation of Leaves, So Are the Generations of Cows, Mice, and Gigolos

- Epilogue

- Bibliography

- General Index

- Index Locorum

- References

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 18 November 2022

- Carpe Diem

- Cambridge Classical Studies

- Carpe Diem

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures

- Acknowledgements

- A Note on Ancient Texts and Translations

- Abbreviations

- Introduction In Search of Present Time

- 1 The Archaeology of Carpe Diem

- 2 A Moveable Feast

- 3 Gathering Leaves

- 4 The Pleasure of Images

- 5 As Is the Generation of Leaves, So Are the Generations of Cows, Mice, and Gigolos

- Epilogue

- Bibliography

- General Index

- Index Locorum

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Carpe DiemThe Poetics of Presence in Greek and Latin Literature, pp. 239 - 281Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2022

- Creative Commons

- This content is Open Access and distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/cclicenses/