At the beginning of his work, Thucydides tells of the early history of Greece, making use of inference and adducing myth as well as material evidence (Th. 1–23). This section is commonly called the ‘Archaeology’, an appellation that was probably coined in the mid-nineteenth century.Footnote 1 Yet, a scholion that describes a passage within Thucydides’ prooemium as ἀρχαιολογία might point to some awareness on the scholiast’s part that this section goes beyond the scope of Thucydides’ work: it deals with prehistory, myths, material remains, and heroic genealogies – in short, something that came to be known as ἀρχαιολογία or antiquitates.Footnote 2 In turn, the present chapter at the outset of this study will begin with an archaeology of the carpe diem motif: it will look at the prehistory of the motif, its myths, material remains, constructed genealogies, and false beginnings.

Thucydides’ Archaeology of early Greek history turns eastward to Troy. A prehistory of carpe diem may take the same direction and discuss the interdependency of Sumerian, Akkadian, Egyptian, Hebrew, Greek, and Roman material. Such attempts have indeed been made.Footnote 3 But a genealogy of carpe diem which makes the Egyptian Harper’s Songs the source of Horace has to remain speculative – much like the genealogies of heroes and the foundations of cities, which constitute Greek ἀρχαιολογία. Indeed, the presence of the carpe diem motif in Chinese poetry should caution us that many parallels between ‘Eastern’ and Greco-Roman material may be accidental.Footnote 4 Nor are we likely to find the origins of carpe diem in a supposedly lyric age of individuality, in which an alleged shift of mentalities makes poets sing of present enjoyment rather than heroic deeds.Footnote 5 If we then cannot answer the question ‘where does it come from?’ in relation to carpe diem, it is perhaps the wrong question. Instead, we may rather ask the question why the origins of carpe diem matter or, better still, how the Greeks constructed the origins of carpe diem. Rather than establishing a historical sequence, I will look at the Greek discourse of the past – that is, their Archaeology of carpe diem.

This chapter’s archaeology of carpe diem will thus be an archaeology in more than one sense; it considers the Greek discourse of ἀρχαιολογία, that is, an interest in material remains, prehistory, and genealogies – an early ancestor of modern archaeology. But the chapter also discusses an ‘archaeology’ of a motif – that is, a constructed origin of a literary mode. Finally, in describing a Greek discourse of the past rather than the Greek past itself, this approach owes something to Michel Foucault’s Archaeology of Knowledge: ‘in our time, history is that which transforms documents into monuments’.Footnote 6

The monument under investigation here is the Sardanapallus epitaph. Attributed to the legendary last king of Assyria, the epitaph became one of the most-often quoted and one of the most openly hedonistic carpe diem texts. Its alleged priority in both temporal terms and terms of hedonism make it a natural starting point for this discussion. The first section deals with the complex Quellenkritik of the epitaph and argues that the Greeks constructed it as an archaeological forerunner of the carpe diem motif in general and carpe diem in epigrams in particular. The Greeks invent the Sardanapallus epitaph in both senses of the Greek verb εὑρίσκω: they both find the epitaph and devise it (the ambiguity would also be true for Latin inuenio). The second section looks at elements of present time and performance in the epitaph. The third section looks at the art of variation in other epigrams dealing with the Sardanapallus epitaph and argues that these epigrams construct an Epicurean ‘archaeology’ of the carpe diem motif. The last section of this chapter analyses how one can read a theatrical performance of Sardanapallus’ pleasures and how the epitaph is adapted in Rome. This chapter will analyse, then, how the Sardanapallus epitaph was constructed as the origin of a Greek tradition of carpe diem. Addressing this question, the chapter engages with the two main themes of this study: evocation of present time and reading carpe diem.

The figure of Sardanapallus has fascinated people for centuries. Indeed, Sardanapallus offers perhaps the only issue on which a classicist can vie with Isaac Newton, qui genus humanum ingenio superauit, as the Lucretian epigram on his statue in the chapel of Trinity College, Cambridge proclaims. For Newton, Sardanapallus was a real king, and Sardanapallus’ alleged existence was one element in Newton’s work on the chronology of the ancient world.Footnote 7 Newton, as well as his contemporaries, took a legend for a fact, but the legend is worthy of investigation. This chapter will look at one of the best-known aspects of Sardanapallus’ legend, his death, and how this is linked to carpe diem.

1.1 The Invention of Carpe Diem

I have what I ate and my kinks, and the pleasures I received in bed. But my many well-known riches are gone.

These words from Sardanapallus’ epitaph were widely known, Strabo tells us (Str. 14.5.9: καὶ δὴ καὶ περιφέρεται τὰ ἔπη ταυτί). Indeed, when Strabo quotes the two lines in his Geography, written in the first centuries ʙᴄ and ᴀᴅ, the lines had already been quoted, imitated, and parodied by Aristotle, Chrysippus, Cicero, and many more, sometimes with slightly varying words, sometimes in a longer version.Footnote 9 And the fame of the epitaph does not stop there. Athenaeus would later talk of people who ‘aspired to the lifestyle of Sardanapallus’ (Ath. 8.335e–337a and 12.530c–531b): the poet Archestratus of Gela, a character from a play, and a man whose epitaph praises hedonism are all said to emulate Sardanapallus; even Homer’s tale of the pleasure-loving Phaeacians is among the texts that are subsumed under the theme of Sardanapallus. Aristotle sees in Sardanapallus the prime representative of a life of pleasure when he discusses three different ways of life that are commonly thought to lead to the good (τὸ ἀγαθόν) or to happiness (ἡ εὐδαιμονία), namely the life of pleasure, the life of politics, and the life of contemplation (EN 1.3 1095b 22; cf. EE 1.5 1216a 16). Other writers link Epicurus’ philosophy with Sardanapallus’ lifestyle. For Athenaeus, Sardanapallus offers the archetype for anyone who aspired to a lifestyle of carpe diem. How did Sardanapallus become this archetype? In order to answer this question, we will uncover layers of the legend of Sardanapallus as we follow a Greek expedition that tries to make sense of his alleged tomb.

Besides the hexameter version of Sardanapallus’ epitaph, a prose version also circulated in Greek culture, which Strabo, for instance, quotes along with the verse version (Str. 14.5.9): Σαρδανάπαλλος ὁ Ἀνακυνδαράξεω παῖς Ἀγχιάλην καὶ Ταρσὸν ἔδειμεν ἡμέρῃ μιῇ· ἔσθιε, πῖνε, παῖζε· ὡς τἆλλα τούτου οὐκ ἄξια (τοῦ ἀποκροτήματος) (‘Sardanapallus, the son of Anacyndaraxes, built Anchiale and Tarsus in a single day. Eat, drink, and fool around, because everything else is not worth this! (“This” refers to the snapping of the fingers)’). The epitaph, Strabo says, was written on a monument that featured a statue of a man snapping his fingers. The story of this epitaph is the story of Greeks who encounter a foreign ancient monument and interpret it as a monument of carpe diem. This story begins on the eve of the Battle of Issus in 333 ʙᴄ, as the army of Alexander the Great comes to Anchiale near Tarsus in South Cilicia, where they see an ancient monument. Writers who accompanied Alexander on his campaign tell of the events in Anchiale. Thus, the Alexander historians Clitarchus and Callisthenes almost certainly will have told of the tomb, though their accounts are lost.Footnote 10 The account of another Alexander historian, Aristobulus, survives; Strabo and Athenaeus give us an almost identical text of the event, which they both attribute to Aristobulus.Footnote 11

Aristobulus’ text arguably also forms the basis of the most detailed description of the encounter in Anchiale, which the second-century-ᴀᴅ historian Arrian provides, though Arrian seems to rely on more than one source.Footnote 12 In Arrian’s account, we enter ‘archaeological’ territory, as he makes inferences about the past based on material evidence: the foundations and circumference of Anchiale’s walls attest to the power this town once had.Footnote 13 As the scene shows remains from a powerful past, Arrian describes the epitaph of Sardanapallus (Anab. 2.5.2–4):Footnote 14

αὐτὸς δὲ ὕστερος ἄρας ἐκ Ταρσοῦ τῇ μὲν πρώτῃ ἐς Ἀγχίαλον πόλιν ἀφικνεῖται. ταύτην δὲ Σαρδανάπαλον κτίσαι τὸν Ἀσσύριον λόγος· καὶ τῷ περιβόλῳ δὲ καὶ τοῖς θεμελίοις τῶν τειχῶν δήλη ἐστὶ μεγάλη τε πόλις κτισθεῖσα καὶ ἐπὶ μέγα ἐλθοῦσα δυνάμεως. καὶ τὸ μνῆμα τοῦ Σαρδαναπάλου ἐγγὺς ἦν τῶν τειχῶν τῆς Ἀγχιάλου· καὶ αὐτὸς ἐφειστήκει ἐπ᾿ αὐτῷ Σαρδανάπαλος συμβεβληκὼς τὰς χεῖρας ἀλλήλαις ὡς μάλιστα ἐς κρότον συμβάλλονται, καὶ ἐπίγραμμα ἐπεγέγραπτο αὐτῷ Ἀσσύρια γράμματα· οἱ μὲν Ἀσσύριοι καὶ μέτρον ἔφασκον ἐπεῖναι τῷ ἐπιγράμματι, ὁ δὲ νοῦς ἦν αὐτῷ ὃν ἔφραζε τὰ ἔπη, ὅτι Σαρδανάπαλος ὁ Ἀνακυνδαράξου παῖς Ἀγχίαλον καὶ Ταρσὸν ἐν ἡμέρᾳ μιᾷ ἐδείματο. σὺ δέ, ὦ ξένε, ἔσθιε καὶ πῖνε καὶ παῖζε, ὡς τἆλλα τὰ ἀνθρώπινα οὐκ ὄντα τούτου ἄξια· τὸν ψόφον αἰνισσόμενος, ὅνπερ αἱ χεῖρες ἐπὶ τῷ κρότῳ ποιοῦσι· καὶ τὸ παῖζε ῥᾳδιουργότερον ἐγγεγράφθαι ἔφασαν τῷ Ἀσσυρίῳ ὀνόματι.

Later he [i.e., Alexander] left Tarsus and arrived in Anchiale on the next day. It is said that Sardanapallus the Assyrian had founded this town. The circumference and the foundations of its walls clearly indicate that the town was great at its foundation and then became very powerful. Near the walls of Anchiale was the tomb of Sardanapallus. On top of it stood Sardanapallus himself, and his hands were brought together as if he was clapping; an epigram in Assyrian characters was inscribed upon the tomb. The Assyrians said that it was written in verse, and its sense was: ‘Sardanapallus, the son of Anakyndaraxes, built Anchiale and Tarsus in a single day. But you, stranger, eat and drink and fool around, because all other human things are not worth this’ – the riddle was referring to the sound of the hand clap. Also, they said that the words ‘fool around’ were naughtier in Assyrian.

The Greeks who look at the surroundings of a once-great city, marvel at a monument of a legendary king, and attempt to make sense of its inscription may remind us of Shelley’s poem Ozymandias (= Ramesses II), in which a ‘traveller from an antique land’ marvels at a fragmented Egyptian statue and its inscription. The inscription extols Ozymandias’ power and his empire, of which nothing remains in the desert. The ‘archaeological’ view of past empires is strikingly similar to the events in Anchiale, and perhaps not coincidentally both the Sardanapallus epigram and the Ozymandias epigram are among passages from Diodorus Siculus which are adopted in English Romantic literature.Footnote 15 Yet, more importantly, Shelley’s traveller also engages in a similar ‘act of reading’ that pays attention to the inscription and its surroundings.Footnote 16 Indeed, the episode of the Sardanapallus epitaph gives us a glimpse into ways of reading epigrams and constructing a carpe diem of the past.

The whole story of the discovery of the Sardanapallus epitaph is rather shady (and not only because of a ‘naughty’ word in the ‘Assyrian’ inscription Arrian reports). As scholars have long recognised, there existed no Assyrian king who matches the characterisation of the ‘Sardanapallus’ in Greek sources: Sardanapallus was a figure of the Greek imagination, a legendary king, who was a symbol of wealth, luxury, carpe diem, and the decay of the Assyrian empire.Footnote 17 Whatever monument the Greeks saw in Anchiale was probably rather different in nature from the one they tell of. A reasonable theory is that the monument was a victory monument of the Assyrian king Sennacherib, whose name the Greeks misunderstood as Sardanapallus.Footnote 18 Already Eduard Meyer had argued that the Alexander historians engage in an interpretatio Graeca of a foreign monument.Footnote 19 The Greeks are then not so much reading an inscription as misreading or constructing it so that meaning is created by the reader rather than the writer. In a manner Stanley Fish could have only wished for, the Greek interpretive community approach a text, read it through their interpretive framework, and create meaning as readers. All we have of the ‘text’ is their reading.Footnote 20

Before we turn in detail to the Greek interpretation of the monument, a short excursus is necessary in order to explore a deeper stratum of the Sardanapallus legend. Alexander’s expedition came to the East with the preformed opinion of Sardanapallus as one of the most famous Assyrians in history and as a character who stood for carpe diem. This cultural formation determined how the Greeks misread the Assyrian monument. It cannot be said with certainty at what point in time the figure of Sardanapallus emerged in Greek culture, but he is mentioned in Greek sources of the fifth century bc: Herodotus mentions his wealth, the antiquarian Hellanicus distinguished between two kings called Sardanapallus – a virtuous one and a less virtuous one – and the name was so well-known that ‘a Sardanapallus’ appears as a stereotype for a flashy inspector in a comedy of Aristophanes.Footnote 21 For a long time scholars had thought that the prose epitaph of Sardanapallus also goes back to this time, as ionicisms in the epitaph seemed to point to a fifth-century-bc Ionian historiographer.Footnote 22 Yet, Walter Burkert showed in an important article that the ionicisms do not go back to an earlier source but were added by the Alexander historians in an attempt to render the original ‘Assyrian’ language through dialect.Footnote 23

The earliest source that tells us of Sardanapallus’ death and associates him with the idea of carpe diem is, then, Ctesias, a Greek historian who was physician to the Persian king (late fifth to early fourth century). Ctesias describes in his Persica how Sardanapallus burns himself along with his precious possessions and his concubines on a pyre when he realises that the enemy forces of the Medes will defeat him.Footnote 24 In Athenaeus’ rendering of Ctesias, Sardanapallus essentially constructed a massive banqueting hall on his pyre, including 150 gold couches with as many tables to accommodate Sardanapallus, his wife, and an improbably high number of concubines. The essence of the carpe diem motif was thus already present in Ctesias: death and dining.Footnote 25 This was not just any death, but the death of the first world empire; nor was it just any feast, but one of enormous proportions, which was directly linked to the end of this empire. Ctesias combines a Greek idea of death and dining with some ‘Eastern’ flavouring; the absence of male aristocrats seems ‘Eastern’, and so does the magnitude of a banquet that includes – if each couch accommodated a single diner – a staggering 150 people, consisting of Sardanapallus and his wife and concubines (in Diodorus, also his eunuchs). Yet, despite some ‘Eastern’ flavouring, most ingredients of Sardanapallus’ banquet are decidedly Greek. In fact, an unbelievably high number of fifty prostitutes had already characterised an extravagant Greek symposium; or, in other words, the staggering number of prostitutes at Sardanapallus’ banquet is part of a Greek sympotic discourse to mark extravagance.Footnote 26 Furthermore, the emphasis on communal reclining during the banquet is more Greek than Assyrian.Footnote 27 Spectacular and ‘oriental’ as Sardanapallus’ death may seem, lurking behind it is the carpe diem of the Greek symposium.Footnote 28

Ctesias’ account almost certainly did not include an epitaph, but his story of a party that ended the Assyrian empire was distilled into an epitaph at a later point.Footnote 29 It is probable, though not certain, that the two famous hexameters quoted at the beginning of this chapter emerged in Greek culture in the fourth century and were already known to the Greeks when they encountered the monument in Anchiale in 333 ʙᴄ.Footnote 30 Whether or not the Sardanapallus epitaph already circulated in Greek culture before 333, the Greeks were certainly eager to add material evidence to a well-known tale and figure – perhaps comparable to their ‘discoveries’ of armour of Homeric heroes.Footnote 31

The popular Sardanapallus legend influenced the Greeks’ interpretation of the monument in Anchiale – and so did their reading practice of epigrams. The role of the reader has been the focus of several studies of Hellenistic epigram.Footnote 32 Crucially, in the case of Sardanapallus’ epitaph, we can observe the act of reading in action. For as Alexander and his fellow travellers from an antique land encounter a difficult inscription, they apply their usual toolkit of reading methods. Let us, for a moment, imagine that a different epigram had been written about the events in Anchiale. In this alternative epigram, the writer might have said: ‘What is the meaning of this monument in an old town in Cilicia? I can discern some foreign letters, and above them is the image of someone in precious Eastern clothes. Is he perhaps a king? And what does the movement of his hands signify? I think I have found a solution: the king is Sardanapallus and he playfully snaps his fingers, because everything in life is not worth more than this snap of the finger!’ There are of course Hellenistic epigrams which describe exactly such an act of reading: the act of making sense of riddling monuments and inscriptions, the attempt to create a literary epigram through reading riddling images, and the act of understanding language as a primarily visual, not an oral, medium.Footnote 33 The difference is that in such Hellenistic epigrams the act of reading is self-conscious and problematised, whereas it is not in the case of the Sardanapallus epitaph;Footnote 34 but I maintain that the act of reading as described in Hellenistic epigrams is based on actual practice in life, which preceded Hellenistic literature.Footnote 35 The Sardanapallus episode thus shows the complex ways in which Greeks were reading epigrams before the advent of either the Hellenistic period or book epigrams.

The reading of the Sardanapallus epitaph is an extremely elaborate reverse Ergänzungsspiel. While Peter Bing described how Ergänzungsspiel in numerous Hellenistic literary epigrams invites the reader to supply the surroundings of the epigram now that the epigram appears isolated from its surroundings on the scroll,Footnote 36 the opposite happens in the case of the Sardanapallus epitaph: monument and surroundings were present to the Greeks in Anchiale, but almost the entire inscription was added (ergänzt) by the readers. The only part of the epitaph that may have belonged to the actual inscription in Anchiale are the place names Anchiale and Tarsus, which could have been part of a victory monument of Sennacherib.Footnote 37

The Greeks supplied the epigram as they tried to make sense of the puzzling Assyrian monument. The monument arguably would have featured a statue or relief of an Assyrian ruler making a gesture with an extended thumb and a pointed index finger, which indicates the presence of a god (ubāna tarāṣu in Akkadian), as Eduard Meyer argued in a seminal article.Footnote 38 The Greeks were puzzled at the odd gesture of the statue and assumed that the inscription must have supplied an explanation. Consequently, they supplied the deictic τούτου in the inscription as a reference to the hand gesture (Aristobulus’ account at Str. 14.5.9): τἆλλα τούτου οὐκ ἄξια (‘everything else is not worth this!’). There arguably was no such deictic marker in the ‘Assyrian’ inscription. Rather, we can see how the Greeks read the material surroundings of the epitaph and construct a text that reflects their interpretation. As a result, we find a deictic pronoun in the epitaph, which can also be found in numerous Greek epigrams as a particularly strong marker of interplay between text and monument.Footnote 39

It is not only the Greeks at Anchiale who were puzzled at a monument. Puzzlement is a reaction that many Hellenistic epigrams describe when viewers look at art.Footnote 40 Already an epitaph roughly contemporary to the events in Anchiale asks the viewer not to be surprised when seeing the accompanying relief that depicts a man mortally wounded by a lion.Footnote 41 In the case of Sardanapallus’ gesture, viewers were also surprised and expected that here, too, the inscription would provide clarity. What is remarkable is that once meaning is constructed, the Alexander historians reverse the dynamics between clues and solutions in their accounts; they quote an inscription including the demonstrative τούτου, which is unintelligible on its own and requires an explanation that relates the pronoun to the statue (Aristobulus’ account at Str. 14.5.9): ‘everything else is not worth this (τούτου)! (“This” refers to the snapping of the fingers)’.Footnote 42 They thus present the image as a supplement to text in the conventional way, though in fact the text was originally a supplement to the image.Footnote 43 Beside the deictic pronoun, there are several other features of the epigram which were arguably formed by the assumptions that Greek readers had about the style of epitaphs. This includes the verse form, the deceased as a first-person speaker, the second-person verbs that address a wayfarer, the paraenetic tone, and the father’s name of the deceased.Footnote 44

As the Greeks believe that they have successfully deciphered the monument, they present their solutions with a rhetoric of expertise. Several features of the narratives of the Alexander historians stress their thorough research methods. This is particularly clear in Arrian’s account. There it is noted that the Greeks inspected the site of Anchiale. The former greatness of this town, inferable from the circumference of its walls, lends credence to the presence of a monument there, which is associated with the Assyrian king best known to the Greeks. The Greeks also stress the foreignness of the inscription, which they deciphered. They mention its Assyrian letters, they note the explanations of locals, and they render the foreign language in Ionic dialect. The different dialect marks the epigram as ‘Asian’ and attempts to give readers a closer impression of the original. And yet, here, just as in the content of the inscription, what is meant to look foreign turns out to be Greek. Other remarks also aim to show expertise; thus, it is mentioned that the epigram was originally written in verse. This was hardly a feature of the Assyrian inscription; rather, the tradition of the well-known verse version of Sardanapallus’ epitaph (or indeed the general Greek tradition of verse epitaphs) influenced the Greek reading here. The boasting about the knowledge of connotations of an Assyrian word for having sex in Arrian can be explained in two ways. If this section goes back to Aristobulus, then Aristobulus already attempted to boast about his scholarly credentials. Alternatively, it is possible that Arrian compares accounts of different Alexander historians and notes the discrepancy between παῖζε and ὄχευε in these sources.Footnote 45 But one thing is clear: as Greek authors argue whether Sardanapallus exhorted readers to ‘fool around’ or to ‘fuck’, they believe they are discussing a reliable source, which they scrutinise with scholarly methods.Footnote 46

Although the Greeks are fascinated with Sardanapallus’ exhortations to present enjoyment, and although they ostensibly stress how one of these exhortations has rather peculiar connotations in Assyrian, in the end all these exhortations look very Greek.Footnote 47 Such exhortations to merriment were at home in sympotic poetry. Thus, we can read the following words in an elegiac fragment of Ion of Chios (fr. 27.7): πίνωμεν, παίζωμεν (‘let’s drink, let’s fool around!’). This is not to say that we can draw a direct line from Ion to the Sardanapallus epitaph, where Arrian and others read ἔσθιε καὶ πῖνε καὶ παῖζε. The alternative ὄχευε in place of παῖζε in some sources lessens the verbal similarity to a degree. Nor should we assume that Ion’s words were of such proverbial nature that the Alexander historians had them in mind. Rather, it seems likely that the fragment of Ion allows us a glance at the type of exhortations that would have been common in many sympotic poems. Thus, we encounter commands that pair πῖνε and παῖζε also in a different elegiac fragment of Ion and – in a carpe diem context – in a fragment from comedy.Footnote 48 Sympotic poets also used pairs of other commands, told their addressees to drink and eat (Thgn. 33: πῖνε καὶ ἔσθιε), to be joyful (or greeted?) and drink (Alc. fr. 401a: χαῖρε καὶ πῶ τὰνδε), and very often simply to drink.Footnote 49 The Sardanapallus epitaph urges to drink and merriment, and its text evokes lyric exhortations to present enjoyment. As the Greeks ostensibly uncover the words of an Assyrian king, they actually engage in an archaeology of their own literary past: Sardanapallus speaks in the familiar language of a Greek sympotic tradition that reaches at least as far back as Alcaeus and Theognis.Footnote 50 Sardanapallus speaks to the Greeks as if he were a symposiast whose banquet they join. The Sardanapallus epitaph, then, unearths traditional commands from Greek sympotic poetry and makes them present; the imperatives that call to merriment construct the fiction of Sardanapallus speaking to his readers in their presence. For a moment we seem to party with Sardanapallus.

Reading the Sardanapallus epitaph and writing it comes down to one and the same thing. The interpretive process of reading signs can create a new text, in a way that is probably best explained by Stanley Fish. The Sardanapallus story tells us much more about the Greek readers than about any Assyrian king. The way in which the Greeks read the Sardanapallus epitaph is notable in particular for two concerns. First, the account of the events in Anchiale points to a sophisticated way of viewing and reading that is commonly associated with the Hellenistic period. Yet, as the events in Anchiale show, this way of reading precedes the Hellenistic period, and it thus offers us valuable information concerning the prehistory of Hellenistic epigram. Second, the way the Greeks read the Sardanapallus epitaph points to an archaeological method with which they attempt to make sense of the distant past. As they apply these methods to the Sardanapallus epitaph they invent its carpe diem message. It seemed to fascinate Greeks that in Anchiale they found themselves in the material presence of Sardanapallus; though long dead, the king seemed to momentarily snap his fingers and tell his readers to live it up. The story of Sardanapallus gained traction after the spectacular discovery in Anchiale, so that Plutarch could say some centuries later that there was no difference between Sardanapallus’ life and his tombstone (Plu. Mor. 336d). Pleasure had become text.

1.2 To Have and Have Not: Sardanapallus in Verse

The game of supplementing the Sardanapallus inscription goes further. The sight of Sardanapallus’ supposed tomb gave rise not only to the prose epitaphs with which the previous section was occupied but also new impetus to the verse epitaph. Thus, one account of Alexander’s campaign, written by Amyntas, tells us that a certain Choerilus made a verse translation of the inscription in ‘Chaldean letters’.Footnote 51 Amyntas gives us a prose paraphrase of Choerilus’ verses, which he apparently took and shortened from an earlier source. Amyntas’ testimony is then secondary, which may account for some confusions within it – not least of which is that the tomb of Sardanapallus is moved from Anchiale to Nineveh in order to suit his supposed place of death.Footnote 52 Despite these caveats, Amyntas’ testimony offers support for placing the verse version of the Sardanapallus epitaph into the environment of Alexander’s campaign; Choerilus of Iasus, a poet who accompanied Alexander on his campaign, responded to the sight of the foreign inscription with his ‘translation’.Footnote 53 In fact, Choerilus was not so much translating an Assyrian inscription into Greek as transferring Greek material to an Assyrian monument. As I briefly mentioned above, two hexameters of Sardanapallus’ epitaph were particularly popular and probably already circulating before Alexander (lines 4–5).Footnote 54 Choerilus, then, added lines 1–3 to the well-known lines 4–5, creating an epitaph of five lines. Later, two more lines were added. I print the text of Lloyd-Jones and Parsons (SH 335 Choerilus of Iasus (?)):

Make yourself happy and enjoy feasts in the knowledge that you are mortal. Nothing is of any use for a dead man. For even I am dust, though I was king of great Nineveh. I have what I ate and my kinks, and the pleasures I received in bed. But my many well-known riches are gone. [These are wise words to live by, and I will never forget them. But let anyone who wants that amass endless gold.]

Choerilus virtually inscribes a proverbial epitaph upon a monument, and as he does so he expands it. His additions in lines 1–3 reflect the physical encounter with the monument during Alexander’s campaign; the admonition to the reader conforms to the prose versions of the epitaph that arose in Anchiale. The cultural dynamics of Choerilus’ verse epitaph are then comparable to those of the prose epitaph: Choerilus’ reading of a foreign monument turns out to be a creative adaption of an already well-known Greek text.

The verses of Sardanapallus’ epitaph are endlessly quoted,Footnote 55 but it is rarely noted how striking they are. The exceptions are perhaps Aristotle and Cicero, who refer to the oldest part of the epitaph, lines 4–5. In De finibus, Cicero discusses Sardanapallus’ epitaph and the possibility of enjoying bodily pleasures when they are past. According to him, Aristotle asked, ‘how could a sensation last with a dead man which even in his lifetime he could only feel while he was actually enjoying it?’ (Aristotle Protrept. fr. 16 Ross = 90 Rose apud Cic. Fin. 2.106 and apud Cic. Tusc. 5.101). To be sure, Cicero here makes a philosophic argument about the nature of pleasure, which relates to more general discussions in Epicurean and Stoic philosophy about what is and is not attainable in life and how self-mastery can be achieved (and the implications of pairing Sardanapallus with Epicurus and past pleasures will be discussed below);Footnote 56 but the comment cuts to the nature of the epitaph and indeed of this book: how does enjoyment work in the past tense?

The paradoxical nature of Sardanapallus’ statement, which Aristotle discerns, is further underlined in its choice of words. The most striking word in the epitaph is arguably its usage of ἔχω. The verb ἔχω is very common in epitaphs. Crucially, though, it almost always takes the deceased as the object, while the subject is the tomb, the monument, or something similar.Footnote 57 The word is formulaic to the extent that Asclepiades would later play with its meaning in an epigram, which begins with the words: ‘I hold (ἔχω) Archeanessa the hetaera of Colophon’ (AP 7.217 = Asclepiades 41 HE). Who is holding the hetaera? A lover or a tomb? The impossibility of determining this is precisely the point of the poem, which plays with generic boundaries, as Richard Thomas has shown. And it is the formulaic nature of ἔχω that makes such a play possible.Footnote 58 Being dead is a question of to have and have not. No dead man can be the agent of ἔχω; there is nothing to have in the underworld; only the tomb has the corpse. This is of course reversed in the Sardanapallus epitaph: Sardanapallus has all the things eaten, his kinks and the pleasures he received in bed. Indeed, the surprising usage of ἔχω is highlighted by the more conventional usage of λείπω: all other things are left behind. The verb λείπω is another formulaic expression on epitaphs. This verb almost always takes the deceased as the subject (in the passive construction of the Sardanapallus epitaph the deceased is of course the logical subject).Footnote 59 Dead people conventionally leave things behind and do not have or own anything anymore. While Sardanapallus does leave almost everything behind, he still has pleasure. Aristotle is rightly struck by this assertion.

A later poem by the Hellenistic poet Machon might be an instructive comparison. In this poem, perhaps influenced by Sardanapallus, Machon tells of an absurd form of convivial death:Footnote 60 having eaten a giant octopus, the dithyrambic poet Philoxenus is told by his doctor that he will die (Machon 9 Gow apud Ath. 8.341a–d). Philoxenus then asks to be served the head of the octopus that had still been left, intending to run off to the underworld having all the things that are his (ἵν᾿ ἔχων ἀποτρέχω πάντα τἀμαυτοῦ κάτω). In this anecdote, Philoxenus succeeds in keeping the things he ate even after death; he has his octopus and eats it. Yet, Philoxenus has of course to go to absurd lengths in order to achieve this, and the ingenuity displayed by Philoxenus illustrates the difficulty in extending possessions and pleasure after death.

The case of Sardanapallus presents an even more extreme version of extending pleasures. The Greeks read that Sardanapallus still has the things he ate, and so forth – in the present tense! This present-tense ἔχω points to present enjoyment, although it is long gone. It constitutes an attempt to bring back present time, which simultaneously points to its loss. And yet, the gap in time is enormous in this case: when Choerilus rewrote the epitaph in Alexander’s times, Sardanapallus had been dead for centuries. Indeed, Choerilus’ addition of three lines emphasises the gap; he inserts a reference to Sardanapallus’ rule over ancient Nineveh right before Sardanapallus tells us in the present tense of his enjoyment (SH 335.3–4): Νίνου μεγάλης βασιλεύσας | ταῦτ’ ἔχω ὅσσ’ ἔφαγον καὶ ἐφύβρισα […] (‘though I was king of great Nineveh. I have what I ate and my kinks […]’). Greeks would have assumed an even longer gap. While modern historians date the fall of Nineveh to 612 ʙᴄ, Greek sources from Ctesias in the fifth century ʙᴄ to Eusebius in the fourth century ᴀᴅ locate Sardanapallus’ reign somewhere in the ninth century ʙᴄ. The mere fact that the Greeks were wrong is of little interest for the present study. Nor does the addition of approximately two centuries matter in itself. Rather, I wish to stress the probable reasoning behind the Greek chronology and how this affects the reading of the Sardanapallus epitaph. For Ctesias and for Alexander’s expedition, Assyrian history preceded Greek history; that is, they locate the end of the Assyrian empire in a time in which there were no known Greek historical events, just a transition period between myth and history proper. Many centuries later, around ᴀᴅ 300, this chronology would become more pronounced when Eusebius compiled chronological tables that synchronised events of world history, for he dates the fall of Nineveh before the first Olympic Games, that is, neatly on the other side of the demarcation line of history.Footnote 61 Naturally, the Greeks who encountered the Sardanapallus epitaph in the fourth century ʙᴄ did not have anything comparable to the sophisticated synchronisation tables of Eusebius. Yet, as Denis Feeney has argued, Eusebius’ tables go back to a Greek historiographical tradition, which in the fifth century ʙᴄ already noted that ‘Eastern’ history preceded Greece’s own.Footnote 62 In other words, Sardanapallus is quite literally pre-history, and his story is best investigated with archaeological methods. The monument from pre-history comfortably stands at the beginning of a Greek tradition of carpe diem. Though in actual fact the fall of Nineveh is roughly contemporary with the poetry of Mimnermus, such a thought would arguably never have crossed Greek minds.Footnote 63 Sardanapallus precedes their tradition.

As Greeks encounter the monument in 333 bc and read the words ‘I have what I ate […]’, they must assume that they encounter a daring present tense that bridges centuries and links pre-history with the present moment. Indeed, Greek epitaphs conventionally assume that they will be read for time to come, so that the words they use and the time frame they construct must be true for an indefinite future.Footnote 64 In the case of the Sardanapallus epitaph, this means not only that this striking present tense has been there for immeasurable time, but also that it will persist in being there. In eternity, Sardanapallus always has his pleasures. While Ctesias described a last monumental banquet Sardanapallus enjoyed, the banquet had become a monument in Anchiale. Expressions from banqueting, the ‘eat, drink, and be merry’ of sympotic lyric, are still present, but they are monumentalised: enjoyment lasts in an eternal present, as people read carpe diem.

1.3 The Art of Variation

An epigram is never alone. It belongs to the core of the genre that inscriptions are surrounded by other inscriptions, vie for the attention of a wanderer, and share a set of formulae. Once collected in books, epigrams create meaning through juxtaposition with neighbouring epigrams, and series of allusive epigrams are common.Footnote 65 The following section turns to the ‘art of variation’ in epigrams similar to the Sardanapallus epitaph.Footnote 66

Following their extensive ‘archaeology’, it is only natural that Greeks treat Sardanapallus as the archetype for similar inscriptions.Footnote 67 Thus, Athenaeus says that ‘a certain Bacchidas, who enjoyed the same lifestyle as Sardanapallus, after his death also has inscribed on his tomb’ the following epigram (GV 1368 apud Ath. 8.336d):

Naturally, no one knows whether Bacchidas’ life really resembled that of Sardanapallus’, as Athenaeus claims. Most likely this conclusion is drawn from the content of the epitaph, which belongs to an otherwise unknown person (‘a certain Bacchidas’; Βακχίδας δέ τις; the name may have reinforced Athenaeus’ interpretation). Yet, there is something to learn from Athenaeus’ reception of the epitaph. At least for a reader who was as learned in literature and sympotic affairs as Athenaeus, the conclusion is clear: through his epitaph and (by extension) through his life, Bacchidas aims to emulate Sardanapallus. Though the Sardanapallus epitaph is not the archetype of the carpe diem theme on epitaphs, it was treated as an archetype in the reception of such epitaphs. Thus, Athenaeus collects material of people who ‘aspire to the lifestyle of Sardanapallus’ and are ‘similar to Sardanapallus’.Footnote 68

The content of Bacchidas’ epitaph is less interesting than its framing by Athenaeus. Walter Ameling collected dozens of parallels.Footnote 69 One aspect in the second line is noteworthy, though: κἠγὼ γὰρ ἕστακ᾿ ἀντὶ Βακχίδα λίθος (‘For I stand here in Bacchidas’ place: a stone’). This line is strongly evocative of the third line of Choerilus’ epigram: καὶ γὰρ ἐγὼ σποδός εἰμι, Νίνου μεγάλης βασιλεύσας (‘For even I am dust, though I was king of great Nineveh’). In both cases the deceased is substituted by inanimate substance – in one case dust and in the other stone.Footnote 70 But whatever Bacchidas’ qualities in life were, he certainly was not the ruler of a world empire. The argumentum a fortiori, ‘even I who used to rule great Nineveh am dust and bones’, does not work in his case. Instead, his epigram plays with the role of the speaker. At least, anyone with knowledge of the Sardanapallus epitaph would most naturally assume that the speaker is the deceased. Only the last three words of the epigram reveal the identity of the speaker: not Bacchidas, but a stone (λίθος). This is the point of the epigram; the sympotic exhortations for the living are contrasted with the voicelessness and non-existence of the deceased. There are no pleasures for Bacchidas anymore, who is replaced by a stone. Bacchidas’ voicelessness is in strong contrast to Sardanapallus’ present-tense voice, which bridges centuries.

An epitaph similar to Sardanapallus’, which predates the events in Anchiale, was found on the tomb of a Lycian dynast. Michael Wörrle dated it to the early fourth century and discussed it in detail (SGO 17/19/03, from where I take the text).Footnote 71

I lie here dead, Apollonius, the son of Hellaphilus. I acted justly; I always had a pleasant life, while I was alive, eating and drinking and fooling around. But go and farewell.

Apollonius’ epitaph confirms the striking nature of the present-tense ἔχω in the Sardanapallus epitaph, discussed in Section 1.2. For in Apollonius’ epitaph we encounter the imperfect εἶχον; he used to have all sorts of pleasures while alive. This is, of course, a much more natural understanding of death, and there are numerous parallels on like epitaphs, in which ἔχω describes the absence of pleasures in the underworld. One deceased, for instance, can speak with the authority of autopsy that ‘down here you have none of these [sc. pleasures]’.Footnote 72 Against the comparison of the Apollonius epitaph and its parallels, the usage of ἔχω in the Sardanapallus epitaph is a remarkable invention.

The cultural dynamics are perhaps the most striking aspect of Apollonius’ epitaph. Wörrle discussed them in some detail, and he showed that Apollonius, a Lycian dynast, here presents himself as adopting a Greek lifestyle. As the son of Hella-philus, a name not attested elsewhere, as Wörrle notes, he might have been prone to philhellenism. If the design of his tomb goes back to Apollonius himself, then he chose to present himself as an aristocratic Greek symposiast in image and text: a Totenmahl-relief depicts Apollonius raising a cup, and the epitaph below picks up Greek sympotic vocabulary. Burkert notes that the writer struggles at points with the Greek metre, and that the expression ἠργασάμην δικαίως might be a syntactic code-switch from a Semitic language, where ‘making justice’ sounds more idiomatic than in Greek.Footnote 73 According to Burkert, the linguistic shortcomings suggest that Apollonius’ family only recently came under the influence of Greek culture and might have spoken more commonly Luwian-Lycian. The question is what part of Greek culture influenced Apollonius or the writer of the epitaph. Wörrle thinks that the mention of justice could have been influenced by fourth-century Greek philosophical thought, and the carpe diem theme by sympotic culture. While the latter seems entirely convincing, the single word δικαίως does not seem a strong enough marker to philosophical influence. In fact, as Wörrle himself sees, Greek lyric already combined drinking, merrymaking, and justice in ways comparable to Apollonius’ epitaph (Ion of Chios fr. 26.16): πίνειν, καὶ παίζειν, καὶ τὰ δίκαια φρονεῖν (‘to drink and to fool around and to have just thoughts’).Footnote 74 The Greek symposium, then, seems to be the cultural institution that the epitaph attempts to emulate throughout. Strikingly, Apollonius’ epitaph displays the opposite dynamics of cultural transfer from the Sardanapallus epitaph; before Greeks in Anchiale believed that they uncovered an ‘Eastern’ sentiment, Apollonius’ epitaph already presents this very sentiment as something Greek for people in the ‘East’.Footnote 75

One parallel epigram to the Sardanapallus epitaph was written by the Cynic philosopher Crates of Thebes (AP 7.326 = Crates 8 Diels = SH 355):Footnote 76

I have what I studied and thought and the venerable things I learnt with the Muses. But delusion seized my many riches.

Crates’ parody follows the Sardanapallus epitaph in the Greek Anthology, and Plutarch also quotes the two epigrams as a pair (Plu. Mor. 546a). ‘Companion pieces’, that is, epigrams which can only be understood as a response to different epigrams, are a common feature of the genre.Footnote 77 Crates’ epigram is such a companion piece, as there is little point in the epigram without the reference to Sardanapallus. Kathryn Gutzwiller thinks that the two epigrams might have circulated orally as a pair before book editions grouped parallel epigrams.Footnote 78 At any rate, Crates’ epigram is certainly an early example of a non-inscriptional parallel epigram.Footnote 79

Crates engages with Sardanapallus’ text as epigram, that is, he recognises epitaphic conventions and makes use of them himself: τὰ δὲ πολλὰ καὶ ὄλβια τῦφος ἔμαρψεν (‘but delusion seized my many riches’). The verb μάρπτω (‘seize’) is not part of the tradition of the Sardanapallus epigram, but is Crates’ invention. Invention is perhaps the wrong word, though, since the verb can be found on numerous epitaphs. On these epitaphs, it is usually Hades, a Moira, or another agent of death who is the subject of the seizing.Footnote 80 The scribes of the Palatine and Planudean Anthologies also recognised the epi-taphic language, but did not recognise the Cynic philosophy. And thus their readings τάφος (P) and τύμβος (Pl) in place of τῦφος (Diogenes Laertius) are telling: in their mind, death takes away everything, and this should be the point of an epigram in Book 7 among other sepulchral epigrams. In fact, Crates replaces the agent of death with the Cynic concept of τῦφος; whether this is best translated as ‘mist’, ‘fog’, or ‘delusion’, at any rate it describes a Cynic concept of an incorrect perception of the world. Crates’ sentence is similar to a famous saying that is usually attributed to Crates’ follower and fellow Cynic Monimus (SSR V G 2): τῦφος τὰ πάντα (‘everything is delusion’). In contrast to the way the scribes of the Anthology understood it, Crates’ epigram does not necessarily refer to death.Footnote 81 A real Cynic already has no possessions in life, so that being dead makes no difference to this; and this is precisely the point of three epigrams on the Cynic Diogenes which play with this meaning of ἔχω.Footnote 82 Crates’ epigram is thus not primarily sepulchral in its purpose, but it plays with sepulchral language. Indeed, his usage of μάρπτω is rather daring: a ‘fog’ or a ‘mist’ cannot easily ‘seize’ anything. Parallels from epitaphs, in which even Charon’s boat seizes someone, might ease the boldness of the iunctura. The act of seizing and grasping is an important action in both epitaphs and carpe diem poems: while Hades seizes young people on epitaphs, carpe diem poems reverse these dynamics and here humans can take control of time and seize it (I will revisit this issue in Chapter 2 and in Chapter 3). Sardanapallus, too, is holding onto his pleasures. Admittedly, ἔχω is an extremely weak haptic word. But since Crates says that he ‘holds’ the things that have not been ‘seized’ (μάρπτω), and Cicero says that Sardanapallus was able to ‘carry off’ his pleasures (aufero), the Sardanapallus epitaph was at least read as a struggle over seizing pleasure.Footnote 83 All this does not make a Callimachus out of Crates. But the epitaph is notable for its play with epitaphic formulae in a non-epitaphic context, something characteristic of many later Hellenistic literary epigrams. The epigram is also notable as an early companion piece. Indeed, if Gutzwiller is right and these companion pieces circulated orally for a while, then Crates’ epigram in many ways looks forward to the development of the Hellenistic book epigram. The Sardanapallus epitaph thus becomes part of a development of reading carpe diem, in which readers add their own versions of the epitaph by adopting epigrammatic conventions. One reason for Crates to attack Sardanapallus is that he is an easy straw man.Footnote 84 A Cynic life in poverty might not appeal to many, but neither does the extreme ‘Eastern’ luxury of Sardanapallus. By contrasting his lifestyle with Sardanapallus’, Crates creates a false dichotomy: you don’t agree with Sardanapallus’ luxury? Then you should join us Cynics in the barrel!

Sardanapallus did not serve as a foil for Crates alone. In the Aetia, Callimachus notably says about symposia that only the fruits of intellectual enquiry proved lasting, whereas the pleasures of wreaths and food quickly faded (fr. 43.12–17 Harder). Like Crates, Callimachus reverses the stance of the Sardanapallus epitaph.Footnote 85 Indeed, Callimachus seems to flag up that he joins in a conversation of people who disagree with Sardanapallus, as he introduces his statement with the words καὶ γὰρ ἐγώ (‘for in my case, too’, polemically taken from the Sardanapallus epitaph at SH 335.3 Choerilus). On the face of it, Callimachus here arguably expresses his agreement with a preceding statement of his interlocutor, now lost. But Callimachus’ assertive answer can also be extended to Crates, with whom he virtually joins in a dialogue. At any rate, soon Crates and Callimachus would be joined in their criticism of the Sardanapallus epitaph. For the Stoic philosopher Chrysippus also adapted Sardanapallus’ epitaph, in this case all five lines of Choerilus (SH 338 = SVF iii.200 fr. 11 apud Ath. 8.337a):Footnote 86

Make yourself happy and enjoy conversations in the knowledge that you are mortal. Nothing is of any use to you once you have eaten it. For I, too, am tattered, although I ate as much as possible and enjoyed myself. I have what I studied and thought, and the good things I experienced along with this. But all the rest is gone, though it was pleasant.

Chrysippus takes over the entire first line of Choerilus without change, and even the initial word of the second is the same, until he substitutes θαλίῃσι for μύθοισι. In the whole piece, only very few words are altered; in line 2 Chrysippus reads φαγόντι instead of θανόντι; in line 3 he reads ῥάκος instead of σποδός (arguably in order to make the epigram sound less sepulchral), and omits the reference to ruling Nineveh. The final two lines are for the most part taken from Crates. A notable change is Chrysippus’ ἡδέα instead of ὄλβια in Choerilus and Crates.Footnote 87 While Chrysippus’ alterations, for the most part, reverse the sense of the epigram, there is no such great difference between ἡδέα and ὄλβια; either way, good things are left behind. And yet, Chrysippus made a point of changing this word, though his epigram elsewhere shows the aim to stick as closely to Choerilus and Crates as possible. But in writing ἡδέα, his epigram alludes to Epicurus’ philosophy, which proclaims that ἡδονή is the highest good. Chrysippus’ method is perhaps slightly more subtle than accusing Epicurus of frequenting a prostitute called Ἡδεία, as others did,Footnote 88 but the motif is the same in either case: a smear-campaign against Epicurus, the philosopher of shady pleasures. By putting Epicurus’ words into Sardanapallus’ mouth, Chrysippus creates a straw man of a truly hedonistic philosophy. Epicurus is then just a follower of Sardanapallus.

Elsewhere Chrysippus claims that the origin of Epicurus’ philosophy is the Hedypatheia of the didactic poet Archestratus of Gela.Footnote 89 The strategy is the same in each case; Epicurus is not a serious philosopher, but simply added the label of philosophy to the teachings of a weak Eastern despot and a debauched gourmand (for good measure the prostitute/erotic writer Philaenis is thrown into the mix). The Sardanapallus epitaph, of course, presents a case of carpe diem, and so does one of the fragments of Archestratus which was perhaps programmatic in Archestratus’ poem and which Athenaeus explicitly associates with Epicurus (Archestratus fr. 60 Olson and Sens apud Ath. 3.101f). Epicurus, however, would arguably not have made this argument.Footnote 90 If death is nothing to us, then it can hardly provide the urgency for hurried pleasure-seeking. Indeed, Lucretius, whose Epicurean credentials are beyond doubt, explicitly condemns this attitude (Lucr. 3.912–30). But for critics of Epicurus, such as Chrysippus, Epicurus can be placed in a line of decadence that begins with Sardanapallus and includes Archestratus and Philaenis. This argument develops the archaeology of carpe diem further, as it constructs a genealogy in which Sardanapallus becomes the origin of Epicurean philosophy. Naturally, the king of Nineveh and the Athenian philosopher sound rather similar once Epicurus’ words are inserted into Sardanapallus’ mouth. The damage was lasting.Footnote 91 Cicero, in discussing Epicureanism in De finibus, still adduces the Sardanapallus epitaph (2.106): in proper Epicurean fashion, Sardanapallus seems to enjoy past pleasures (bona praeterita).

1.4 The Professor of Desire, Sardanapallus in Rome

A fragment from comedy directly precedes Chrysippus’ ‘emended’ version of the Sardanapallus epitaph in Athenaeus. This fragment is allegedly a passage from a lost play of Alexis, a playwright of Middle Comedy. Athenaeus gives its title as Ἀσωτοδιδάσκαλος (‘The instructor in profligacy’). Athenaeus’ editing choice shows that he noticed the similarity between this passage and the Sardanapallus epitaph. Indeed, the speaker of the passage seems to be virtually responding to Crates and Chrysippus, as he launches into an attack against philosophers.Footnote 92 In his introduction to the passage, Athenaeus says that it tells how a slave called Xanthias exhorts his fellow slaves to live it up ([Alexis] fr. 25 apud Ath. 8.336d–f):

Why are you talking this nonsense and are making a mess of the Lyceum, the Academy, and the gates of the Odeon, the gibberish of the sophists? None of this is any good. Let’s drink! Let’s drink up, Sicon, Sicon! Let’s enjoy ourselves as long as we can make ourselves happy! Live it up, Manes! Nothing gives more pleasure than the belly. Only the belly is both your father and your mother. But the prestige from ambassadorships and generalships is pompous vanity and rings as hollow as dreams. At the destined time some god will finish you off. All you’ll have is what you eat and drink; all the rest is dust: Pericles, Codrus, Cimon.

The textual history of this fragment is difficult. Athenaeus tells us that he has found no play called Ἀσωτοδιδάσκαλος in over 800 Middle Comedies (though the number might be conventional), and he says that it was neither catalogued by Callimachus, nor by Aristophanes, nor in Pergamum. Athenaeus encountered the excerpt in the work of the philosopher Sotion of Alexandria. As the fragment further includes some linguistic oddities and a probable anachronism, it is likely that it was not authentic, as has been argued in detail by Geoffrey Arnott.Footnote 93

Arnott originally assumed that the play was forged for reasons of financial gain, but revised this assumption later, and in his commentary argued that the passage is a ‘bogus quotation designed to illustrate the enemy viewpoint in an anti-Epicurean pamphlet composed in the third or second century’.Footnote 94 This is a very plausible suggestion. Indeed, the association of Epicurus with Sardanapallus is arguably more pronounced than Arnott assumes. For he argues that Ettore Bignone, who earlier linked the passage to Epicureanism, ‘fails to prove any positive relationship between Epicurus and epitaph beyond their common hedonism’.Footnote 95 Yet, the case of Chrysippus, who makes Sardanapallus sound like Epicurus, points to this relationship. The fact that Cicero adduces the Sardanapallus epitaph in a discussion of Epicurean pleasures further strengthens the case (Fin. 2.106). Just like Chrysippus, Pseudo-Alexis merges the Sardanapallus epitaph with Epicurean sentiments. This includes notably the rejection of public offices in lines 8–9,Footnote 96 and I wonder if the equation of public prestige with hollow sound is not a faint ring of the assertion of the Sardanapallus epitaph, according to which any human achievements do not even equal the sound of snapping of the fingers. The mention of the belly also looks suspiciously like an attack on Epicurus.Footnote 97 Arnott disagrees and thinks that the passage on the belly lacks a direct verbal tie to Epicurus. But need there be one? Is it not more significant that the belly appears as a stock motif in anti-Epicurean writing rather than in Epicurus? And here the charge is clear: Epicurus is a philosopher of the belly. Indeed, the closest parallel for the belly in Pseudo-Alexis is a fragment from New Comedy, in which Hegesippus attributes the saying to Epicurus that men always seek pleasure and that ‘nothing is better than chewing’ (τοῦ γὰρ μασᾶσθαι κρεῖττον οὐκ ἔσθ’ οὐδὲ ἕν | ἀγαθόν, Hegesippus Philetairoi fr. 2.5–6).Footnote 98 As a mock-quotation of the Sardanapallus epitaph in a philosophic context, the Ἀσωτοδιδάσκαλος is comparable to Crates’ and Chrysippus’ versions of the Sardanapallus epitaph. Moreover, there is perhaps another such text, if Adelmo Barigazzi is right to assume that a Hellenistic iamb, which also adopts the Sardanapallus epitaph, would have included in lost lines some criticism on this epitaph.Footnote 99

The slave Xanthias in Pseudo-Alexis asserts that it is only possible to hold onto pleasures, whereas everything else is void. While Pseudo-Alexis expresses the same sentiment as the Sardanapallus epitaph and also copies its phrasing, the words do not refer to Sardanapallus anymore; we are still told that worldly prestige is dust and ashes, but the prestige is now associated with the Athenians Pericles, Codrus, and Cimon rather than with the Assyrian king. The sentiment is translated and made present to suit a conversation in Athens; the fiction of the Eastern king is given up. And so is the fiction of the epitaph; Choerilus’ σποδός (‘dust’) makes it into the text of Pseudo-Alexis and may remind us of its epitaphic heritage, but the text of Pseudo-Alexis constitutes a piece of a conversation, not an inscription. As the fragment abandons the illusion of the epitaph, Xanthias in Pseudo-Alexis exhorts with first-person-plural verbs in the present tense: πίνωμεν, ἐμπίνωμεν, ὦ Σίκων, <Σίκων>, | χαίρωμεν, ἕως ἔνεστι τὴν ψυχὴν τρέφειν (‘Let’s drink! Let’s really drink, Sicon, Sicon! Let’s enjoy ourselves as long as we can stay happy!’). These are exhortations among the living, where everyone – speaker as well as addressees – can join in the drinking.Footnote 100 As we have seen, such exhortations are evocative of sympotic poetry which urges symposiasts to enjoyment (Ion of Chios fr. 27): πίνωμεν, παίζωμεν· ἴτω διὰ νυκτὸς ἀοιδή, ὀρχείσθω τις (‘let’s drink, let’s fool around; let singing continue through the night, let someone dance’). The theatrical performance seems to approximate the performative quality of lyric carpe diem: leaving behind the heritage of stones and inscriptions, the comedic fragment seems to enact present enjoyment.Footnote 101 And yet, also this passage in the tradition of Sardanapallus is at least as much about reading carpe diem as it is about performing carpe diem. The forgery imagines a scene never to be performed, but always to be read by anti-Epicureans with scorn; they neither hear the call πίνωμεν at the symposium, where they can enact it, nor do they watch it on stage, where others perform it, but they read carpe diem and reject it.

It is not only Pseudo-Alexis who inserts the Sardanapallus epitaph into character speech.Footnote 102 Sardanapallus’ epitaph continued to fascinate readers, and still in Latin epic we find a version of it inserted. Rabirius was an epic poet who probably lived under Augustus and wrote a work that included a description of Mark Antony’s death.Footnote 103 Seneca provides a quotation from this scene along with some context (Sen. Ben. 6.31 quoting Rab. poet. fr. 2 Courtney, FLP = 2 Blänsdorf, FPL = 231 Hollis, FRP):

egregie mihi uidetur M. Antonius apud Rabirium poetam, cum fortunam suam transeuntem alio uideat et sibi nihil relictum praeter ius mortis, id quoque, si cito occupauerit, exclamare:

hoc habeo, quodcumque dedi.

I think that in the poet Rabirius Mark Antony put it very well, when he witnessed that his fortune went to someone else and that nothing was left to him except the right to determine his own death, and that too only if he seized it quickly; then he exclaimed: ‘I have whatever I have given away.’

Only half a hexameter survives of Rabirius’ scene of Mark Antony’s death. The commentators have long noticed that this fragment adapts and reverses Cicero’s translation of the Sardanapallus epitaph by addition of one letter (Tusc. 5.101):Footnote 104 haec habeo, quae edi, quaeque exsaturata libido | hausit; at illa iacent multa et praeclara relicta (‘I have what I ate and all the kinks I enjoyed fully. But my many well-known possessions are gone’). The main point of Rabirius’ fragment is apparently to contrast Mark Antony’s well-known generosity with Sardanapallus’ self-centred hedonism; it is his generosity that gives Mark Antony lasting benefits.Footnote 105 Whether it would have mattered for Rabirius’ poem that both Sardanapallus and Mark Antony committed suicide as the control of a world empire was slipping away from them cannot be said with certainty on the basis of the short fragment. But what we can say is that Rabirius lets Mark Antony virtually speak a ‘self-epitaph’;Footnote 106 that is, the résumé that Mark Antony draws at the end of his life consciously evokes the form of a tomb inscription. For we can find the words of the Sardanapallus epitaph also as a motif on Roman tomb inscriptions (Reference CourtneyCourtney (1995) 160, no. 169 = CLE 244 = CIL vi 18131): quod edi bibi, mecum habeo, quod reliqui perdidi (‘I have what I ate and drank. I have lost what I left behind’). Another Roman proclaims on his epitaph in Sardanapallus’ fashion that ‘he has everything’ (omnia se habet), before he lists sensuous pleasures.Footnote 107 The Sardanapallus epitaph was, then, both part of discussions in Roman philosophy about the good life, as Cicero attests, and a very real material presence, as the epitaphs show which extol the lasting benefits of the hedonistic life (not all of them may have thought of Sardanapallus, but for a leaned reader the link is clear).

Scholars have noticed how epitaphic gestures in Vergil and other poets are important techniques through which poets engage with epigrammatic qualities, such as the medium of written text, its public nature, the materiality of everlasting stone, or the role of the reader.Footnote 108 Rabirius, in turn, joins an epigrammatic tradition of rewriting the Sardanapallus epitaph; Crates, Chrysippus, and others have rewritten the Sardanapallus epitaph in order to flaunt their philosophies, which stand in opposition to Sardanapallus’ lifestyle. As Rabirius lets Mark Antony look at his past life at one of the most momentous points of Roman history, we are invited to compare him with Sardanapallus, whose epitaph espouses momentary pleasures and carpe diem. The gesture towards epitaphs, texts which by their very nature keep people in memory and memorialise them, here becomes also part of an intertextual memory that looks back at the various versions and rewritings of the Sardanapallus epitaph.Footnote 109 Rabirius’ adaption of the Sardanapallus epitaph brings us to Augustan Rome. In the next chapter we will turn to carpe diem poetry under (and about) Augustus.

This chapter has traced the archaeology of carpe diem, as Greeks try to make sense of a monument in Cilicia. Their reading of the monument proved extremely influential. Sardanapallus is made to stand at the beginning of a tradition of carpe diem, and anyone else – whether it is the philosopher Epicurus or someone who chose similar sentiments on his tombstone – becomes part of a constructed genealogy of carpe diem which begins with the legendary Assyrian king. At least since the Greeks saw a monument in Anchiale in 333 ʙᴄ, Sardanapallus’ carpe diem has been associated with reading and writing. In reading his inscription, Greeks wrote it, and the subsequent history of the Sardanapallus epitaph has been one of rewriting it by adopting epigrammatic conventions. And yet, some of these texts also evoke presence and performance: Choerilus’ Sardanapallus epitaph speaks in the present tense.Footnote 110 Though it is centuries old, Sardanapallus’ enjoyment is always present.

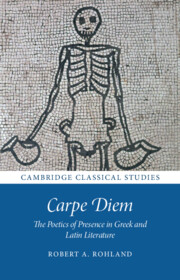

A Roman statue provides a postscript to Sardanapallus’ story. Sardanapallus continued to fascinate and one Roman, who may have regarded Sardanapallus as a model of hedonism, wrote the name ΣΑΡΔΑΝΑΠΑΛΛΟΣ upon a Dionysus statue, thus effectively transforming the god of wine into the Assyrian king (Figure 1.1).Footnote 111 Another misinterpretation of a statue (in this case perhaps a conscious one), another inscription added to a statue finally allows a Roman to be in the material presence of Sardanpallus.

Figure 1.1 Statue of ‘Dionysus Sardanapallus’