Why a book on rewilding?

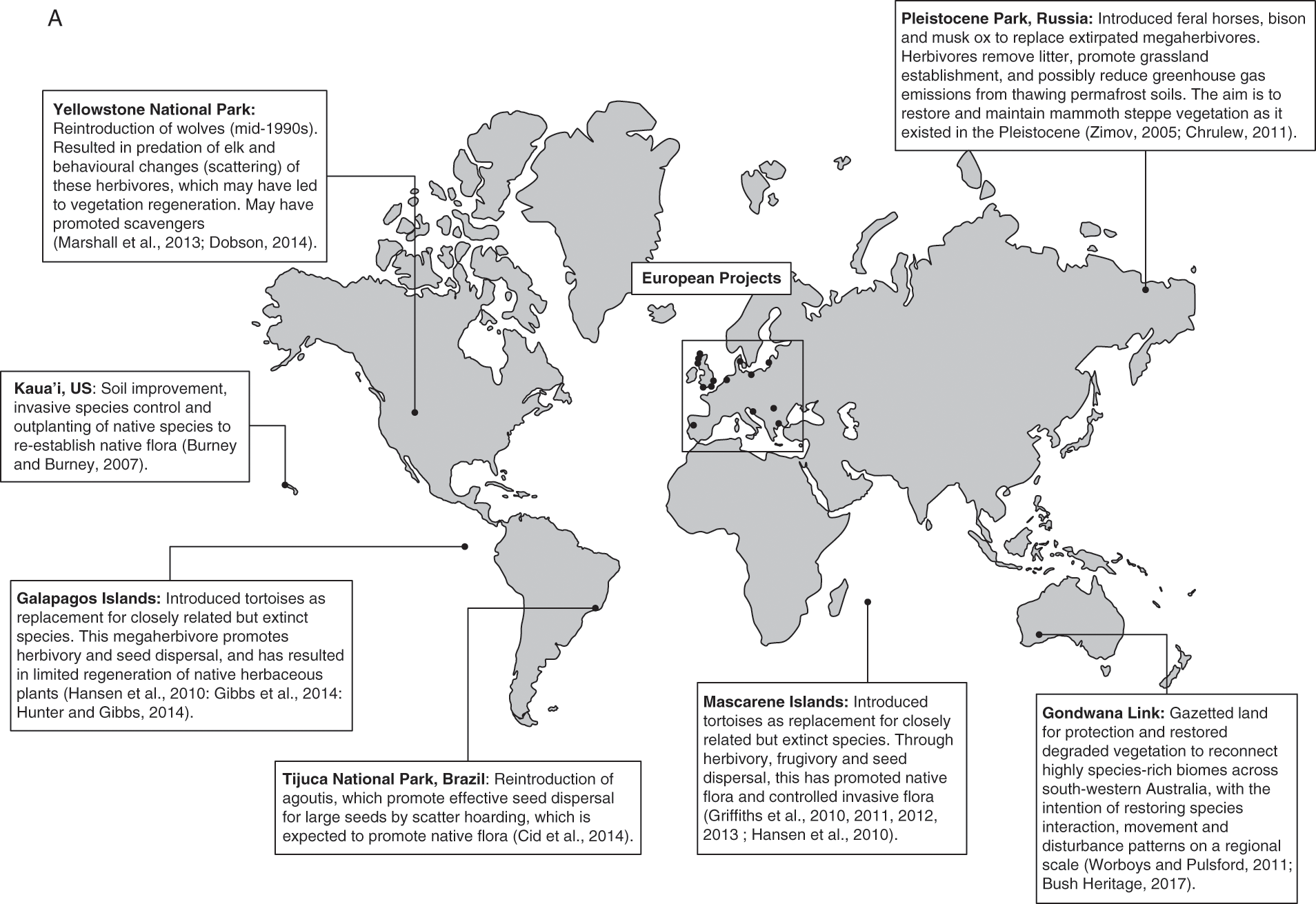

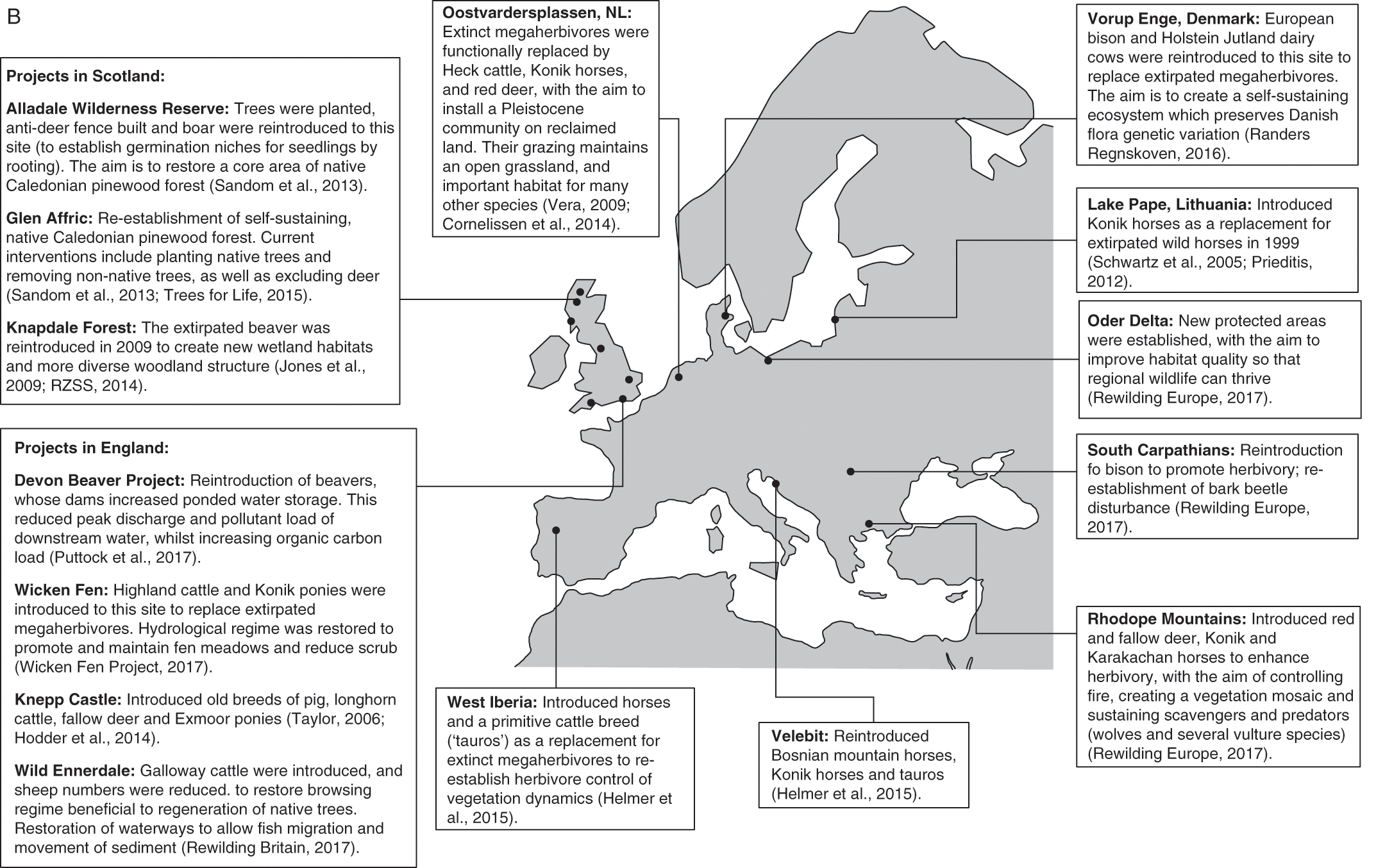

Rewilding is a novel and rapidly developing concept in ecosystem management, representing a transformative approach to conserving biodiversity. Originally defined as a conservation method based on ‘cores, corridors, and carnivores’ (Soulé and Noss, Reference Soulé and Noss1998), the term is now broadly understood as the repair or refurbishment of an ecosystem’s functionality through the (re-)introduction of selected species. Although the term first occurred in print in 1990, its popularity only started to grow substantially over the past decade; during this time, rewilding has moved from a theoretical concept to a practical idea. It is currently being hailed by many as a potentially cost-effective solution to reinstate vegetation succession, reactivate top-down trophic interactions and predation processes, and improve ecosystem service delivery through the (re-)introduction of ecosystem engineers (Pettorelli et al., Reference Pettorelli, Barlow and Stephens2018). Several rewilding projects have now been implemented in multiple countries around the world (Figure 1.1), all being expected to hold potential for enhancing local biodiversity, ecological resilience, and ecosystem service delivery (see e.g. Lorimer et al., Reference Lorimer, Sandom, Jepson, Doughty, Barua and Kirby2015; Pereira and Navarro, Reference Pereira and Navarro2015; Svenning et al., Reference Svenning, Pedersen and Donlan2016).

Rewilding has clearly attracted the attention of practitioners and the general public, as well as national and international bodies concerned with the management of our environment. Policy-makers are increasingly setting up inquiries, briefs, committees, and task forces to assess the potential opportunities associated with rewilding approaches. Similarly, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Commission on Ecosystem Management has recently launched a task force on rewilding (IUCN, 2017). Yet the more sensational connotations of the early proposals for rewilding, such as reintroducing native predators or introducing exotic megafauna (Donlan et al., Reference Donlan, Greene and Berger2005), fuel criticism on scientific, aesthetic, legal, political, economic, and cultural grounds (Lorimer and Driessen, Reference Lorimer and Driessen2014; Arts et al., Reference Arts, Fischer and van der Wal2016; Bulkens et al., Reference Bulkens, Muzaini and Minca2016; Nogués-Bravo et al., Reference Nogués-Bravo, Simberloff, Rahbek and Sanders2016). Critics point to uncertainties and difficulties associated with the definition of rewilding and the practical implementation of rewilding projects. Of particular concern are issues related to the definition and consideration of appropriate ecological baselines and spatiotemporal scales when designing rewilding initiatives. There are also doubts about the extent to which ecological processes could resume significance in human-dominated landscapes. Other challenges include defining the role of humans in rewilded landscapes; aligning rewilding with legal, management and cultural categorisations and frameworks for species and lands; realistically evaluating costs and benefits of potential rewilding initiatives; as well as improving the monitoring and assessment of these projects (Pettorelli et al., Reference Pettorelli, Barlow and Stephens2018).

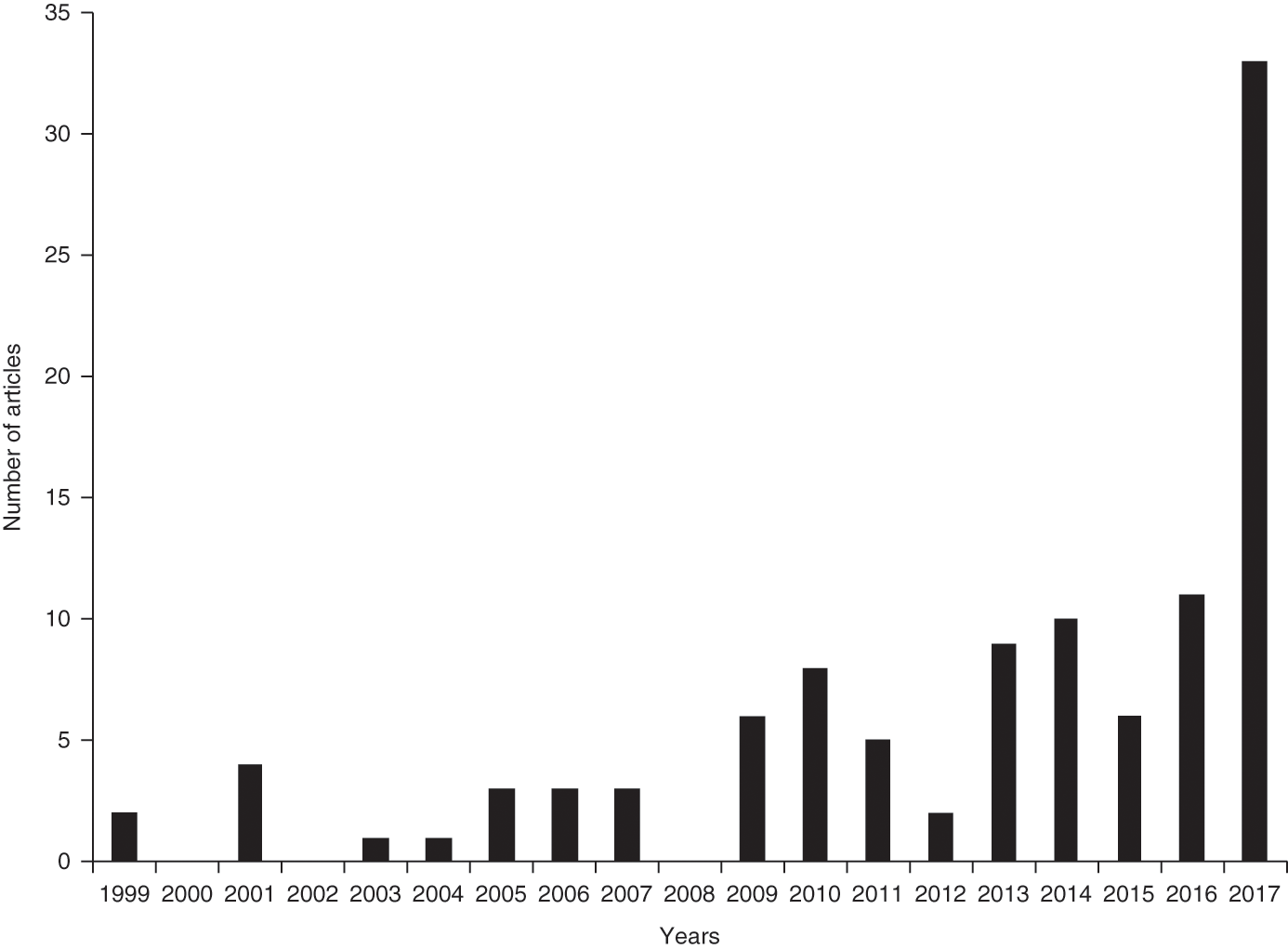

As applied scientists heavily involved with the management of natural resources in various countries and regularly confronted with the realities of planning for the delivery of ecological outcomes in human-dominated systems, we believe now is the time to synthesise available information on the benefits and risks, as well as the economic and sociopolitical realities, of rewilding as a conservation tool. Literature relevant to rewilding discussions has grown quickly over the past few years (Figure 1.2), yet until now there is no scientific book written by world leaders in the field that addresses rewilding with a global and inclusive perspective, or that examines rewilding in the context of social–ecological systems. To address that need, this book (1) introduces key rewilding definitions and initiatives and highlights their differences/similarities; (2) reviews matches and mismatches between the current state of ecological knowledge and the stated aims of rewilding projects; (3) discusses the role of humans in rewilding initiatives; and (4) highlights the merits and dangers of rewilding approaches. It does so by capitalising on the wealth of studies available in the fields of restoration ecology, reintroduction and conservation biology, social sciences, and conservation psychology to examine the concept of rewilding in a critical and objective light. This comes at a time when the field of conservation science is going through a difficult and controversial stage of redefinition, with pragmatism challenging purism (Kareiva and Marvier, Reference Kareiva and Marvier2012). The pace of global change throws the definition of restoration ecology into question (Rohwer and Marris, Reference Rohwer and Marris2016) and novel ecosystems are gaining acceptance as inevitable and irreversible stages in some ecological transitions (Miller and Bestelmeyer, Reference Miller and Bestelmeyer2016). There is a need for new directions for environmental management to move in – going back is no longer an option – and rewilding stands as a candidate concept to be evaluated for certain systems under certain conditions. One could argue that rewilding opens a fresh perspective on the practice of ecological conservation, challenging our relationship to the natural world, encouraging a more interdisciplinary approach to environmental management. However, deciding whether that argument holds merit requires a well-researched, comprehensive overview of the roots, meaning, applications, and challenges of the rewilding concept. Our goal here is to provide exactly that.

Where does rewilding originate from and what does it mean?

Rewilding is believed to have been first discussed by Dave Foreman in 1992, and its definition has been evolving ever since (Chapter 2). This evolution, to a certain extent, captures the changing trends that have shaped conservation biology over the past decades, providing a key outlook on how priorities and leading ideas have switched as our ecological understanding improved over time. Understanding current rewilding discussions is difficult without knowing about the history of the concept and without an appreciation of the link that connects rewilding to the concept of wilderness, an arguably subjective notion that tends to evoke landscapes where natural processes are permitted to operate without human interference. Articulating the link between wilderness and rewilding is indeed central to understanding the diversity of views on rewilding, and to exposing many of the values and politics that have been deep-rooted in modern conservation practice. What is ‘wild’ for some can be described as ‘dominated’ by others, and there is a vast diversity of perceptions of what the wild resembles and what natural means (Jørgensen, Reference Jørgensen2015). These perceptions vary geographically and culturally, can be linked to people’s access to nature, but importantly are ultimately underpinned by clear social constructs that may influence how rewilding projects are being designed and implemented (Carver et al., Reference Carver, Evans and Fritz2002; Diemer et al., Reference Diemer, Held and Hofmeister2003; Bauer et al., Reference Bauer, Wallner and Hunziker2009; Chapter 3).

The use of the term ‘rewilding’ is increasing in the peer-reviewed literature (Figure 1.2), but it has different meanings for different people, and also different framings, which we discuss later. There are three main themes in the current definitions (Table 1.1), the first being the resumption of wildness, by which degraded areas may regain biodiversity and develop into undefined future states without further interference, and not necessarily with any further utility to humans (Lorimer et al., Reference Lorimer, Sandom, Jepson, Doughty, Barua and Kirby2015; Corlett et al., Reference Corlett2016). The second theme is about reintroducing extirpated species (or their substitutes) so that an ecosystem may resume a semblance of its former functionality, with potential benefits to humanity (Naundrup and Svenning, Reference Naundrup and Svenning2015; Prior and Brady, Reference Prior and Brady2017; van der Zanden et al., Reference van der Zanden, Verburg, Schulp and Verkerk2017). Finally, an emerging theme recognises that biodiversity exists within constantly changing social–ecological systems in which perceived costs and benefits dictate which parts of wildness stay or go. The focus of this theme is the self-sustaining functionality of an ecosystem, which managers might not necessarily restore to a former state but could reorganise to provide ecosystem services with minimal intervention under prevailing environmental conditions (Law et al., Reference Law, Gaywood, Jones, Ramsay and Willby2017; Pettorelli et al., Reference Pettorelli, Barlow and Stephens2018). All three themes have applications in different places and circumstances, but they share a common departure that distinguishes rewilding from restoration: rewilding is about choosing new trajectories of change towards wildness in future undefined states; restoration is generally about reversing a trajectory of change to return to a defined previous state.

Table 1.1. Main broad definitions of rewilding, as proposed over the past five years.

| Definition | Key points | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| ‘Rewilding has multiple meanings. These usually share a long-term aim of maintaining, or increasing, biodiversity, while reducing the impact of present and past human interventions through the restoration of species and ecological processes’ | Focus on reducing impacts of management interventions | Lorimer et al. (Reference Lorimer, Sandom, Jepson, Doughty, Barua and Kirby2015) |

| Targets ecological processes and species restoration | ||

| ‘Reintroduction of extirpated species or functional types of high ecological importance to restore self-managing functional, biodiverse ecosystems’, ‘emphasises species reintroductions to restore ecological function’ | Focus on (re)introductions | Naundrup and Svenning (Reference Naundrup and Svenning2015) |

| Targets ecological functions | ||

| ‘Rewilding implies returning a non-wild area back to the wild … This is the definition adopted in this review, except that I have followed normal usage in also including increases in relative wildness, i.e., from less wild to more wild’ | Targets levels of wilderness | Corlett et al. (Reference Corlett2016) |

| ‘A process of (re)introducing or restoring wild organisms and/or ecological processes to ecosystems where such organisms and processes are either missing or are “dysfunctional”’ | Focus on (re)introductions | Prior and Brady (Reference Prior and Brady2017) |

| Targets species composition and ecosystem processes | ||

| ‘The focus [of rewilding philosophy] is on benefits of renewed ecosystem function or processes (e.g. water storage, enhanced water quality, biodiversity support), rather than classic restoration thinking where a community converges towards a predefined target via a predictable trajectory’ | Focus on non-predictable trajectory | Law et al. (Reference Law, Gaywood, Jones, Ramsay and Willby2017) |

| Targets ecosystem function/process | ||

| ‘The idea that unproductive and abandoned land can serve as new wilderness areas (“rewilding”) i.e. self-sustaining ecosystems close to the “natural” state often supported by (re-)introduction of large herbivores and habitat protection for carnivores and other species’ | Focus on (re)introductions and habitat protection | van der Zanden et al. (Reference van der Zanden, Verburg, Schulp and Verkerk2017) |

| Targets self-sustaining ecosystems | ||

| Supports low level of interaction between people and landscape | ||

| ‘The reorganisation of biota and ecosystem processes to set an identified social–ecological system on a preferred trajectory, leading to the self-sustaining provision of ecosystem services with minimal ongoing management’ | Acceptance of change, emphasis on reorganisation rather than restoration, focus on the social–ecological system and desired ecosystem services | Pettorelli et al. (Reference Pettorelli, Barlow and Stephens2018) |

Introducing the different framings of rewilding

The concept of rewilding was originally framed as a call for large, connected wilderness areas to support wide-ranging keystone species such as apex predators (Soulé and Noss, Reference Soulé and Noss1998). Since then, the multiple definitions of rewilding (Table 1.1) relate to successive framings that have not necessarily replaced earlier ones. At present, there are four distinct framings that can be recognised in the literature: Pleistocene rewilding; trophic rewilding; passive rewilding; and ecological rewilding.

Pleistocene rewilding generally refers to restoring ecological processes lost because of the late-Pleistocene megafaunal extinctions. Josh Donlan and colleagues (Reference Donlan, Greene and Berger2005) galvanised conservation biology with this bold and arguably overambitious framing of rewilding that invokes taxonomic substitution, using proxy species from other continents to serve the functions of extinct megafauna. Many describe Pleistocene rewilding as an absurd concept formulated by a small group of conservation biologists with little understanding of the practicalities and politics of animal translocations. Others, however, see this framing of rewilding as heuristically useful for developing the idea that extinct species leave vacant niches, and those vacancies have far-reaching ramifications through the ecosystem. Dealing with those ramifications requires an appreciation of the importance of conserving ecosystem processes and functions, and an acknowledgement that unorthodox management interventions may be required where all else fails.

Trophic rewilding specifically frames the reactivation of top-down trophic interactions. This framing is conceptually close to Pleistocene rewilding, but discards its historical benchmark and retains its main theoretical tenants: (1) megafaunal processes are important for ecosystem structure and functioning, promoting overall biodiversity in various ways, notably via top-down trophic effects fostering environmental heterogeneity; (2) rich megafaunas have been typical worldwide on evolutionary timescales and so modern species assemblages have evolved in, and are therefore adapted to, megafauna-rich ecosystems; (3) losses of megafauna from recent to distant times have led to ecosystem changes and biodiversity losses.

Passive rewilding refers to abandoned post-agricultural landscapes that are no longer actively managed, a framing that is current especially in Europe. It could be seen as an alternative to classic environmental management, substituting management for nature with management by nature. This framing of rewilding is conceptually close to ecological rewilding, which involves limited active management to facilitate natural processes and allow them to regain dominance.

Acknowledging the human dimension of rewilding

Rewilding does not happen in a vacuum. Social, cultural, psychological, economic, and political dimensions will all affect the ultimate success of any rewilding intervention. As such, it is impossible to discuss rewilding without considering its human dimensions, acknowledging that humans are key to the success, and the failure, of rewilding initiatives. Importantly, human responses to rewilding shed light on our responses and relationship with nature, providing us with important insights that can inform adaptive management and sustainable development.

Individual reactions to conservation actions are shaped by our perceptions of nature and our link to it, with people generally adopting one of four possible general attitudes towards nature: being a nature lover; a nature sympathiser; a nature-connected user; or a nature controller. These attitudes are not fixed in time and people may change their attitudes towards nature as their stage of life, place of residence, level of knowledge and experience change. Interestingly, rewilding is predominantly discussed in the context of developed countries, commonly in association with opportunities to increase nature’s presence in urban settings. Yet living with nature in urban settings could have beneficial, but also harmful and unpredictable outcomes, which could ultimately affect people’s support for rewilding initiatives. So far, little research has been done to deepen our understanding of the drivers shaping our relationship with wilderness, meaning that our current ability to predict and mitigate negative attitudes to rewilding projects is low.

Discussing the challenges associated with rewilding

Rewilding poses daunting ecological and societal challenges to practitioners who are left in charge of initiating and overseeing such projects. Any formulation of a rewilding project is underpinned by a number of ecological assumptions, which, if not met, could lead to damaging outcomes for the entire social–ecological system. For example, a badly designed rewilding project could increase the risk of new, unwanted ecological interactions (Nogués-Bravo et al., Reference Nogués-Bravo, Simberloff, Rahbek and Sanders2016). Ideally, the initiation of these projects should thus be preceded by a clear identification of the overarching goals, guiding principles, available management options, and key assumptions. Experience so far suggests that these foundational stages are rarely negotiated in full.

Carnivore (re-)introductions are often critical to rewilding discussions from the onset, because of their linkages to the restoration of ecological processes, yet these are known to be particularly challenging. Our general scientific understanding of the factors driving translocation success indeed remains relatively poor, which is a problem for rewilding initiatives placing translocations at the centre of their management approach. Recent experience from Europe has shown there is enormous scope for large carnivore recovery, even in shared and human-modified landscapes, but the extent to which we can expect large carnivores to resume their ecological functions in the rewilded landscapes of the Anthropocene is currently unknown. Additionally, evidence that rewilding approaches can restore top-down control of ecosystems remains equivocal.

To be successful, rewilding approaches need to demonstrate cost-effectiveness. Conservation funds are always limited and investments cannot be justified for projects that might fail or return low conservation benefits. As of present, rewilding is associated with fluid and unscripted targets as well as indeterminate outcomes. This lack of clarity extends to the monitoring and assessment of rewilding projects, begging critical questions such as ‘how do we know that the rewilding project we paid for is successful?’ or ‘how do we know when success is met?’

Conclusions

This edited volume brings together, for the first time, leading authors in the rewilding literature who were each charged with synthesising the current thinking on their speciality within this field. The book was designed to provide a comprehensive, interdisciplinary overview of rewilding that outlines key concepts and details informative case studies. The need for an inclusive, scientifically rooted discussion on rewilding exists because of the unprecedented rates of environmental change in the Anthropocene, which call for a paradigm shift from focusing on the preservation of individual species to the enhancement of ecosystem health and processes, and for new and pragmatic options for mitigating the degradation of biodiversity and ecosystem services. Until now, however, rewilding has lacked the conceptual foundation needed for it to develop as a forward-looking, science-based, and policy-supported option. Our objective will be met if this book provides that foundation.