Food-based dietary guidelines (FBDG) are documents with context-specific principles and recommendations on food and nutrition that express the position of governments on how healthy eating is defined. They are intended for use by the general public to educate people on healthy diets, provide the basis for food and nutrition policies, nutrition education programmes, and dietary planning for individuals and communities, and evaluate and monitor populations(1,2) .

In response to some recent public health challenges, such as changes in food systems and people’s health conditions, as well as the emergence of new paradigms of healthy diets(3–6), FBDG are evolving into broader perspectives. Some FBDG incorporate new content, such as food combinations (meals), ways of eating, food safety considerations, lifestyle and, more incipiently, sustainability(1–Reference Gonzalez Fischer and Garnett5).

Aligned with these new approaches and recommendations, cooking is emerging as a strategy to encourage people’s adherence to healthy foods and meals(3–6) and improve diet quality(Reference Wolfson, Leung and Richardson7–Reference Mills, Brown and Wrieden10). In addition, cooking at home, especially when using mainly fresh or minimally processed foods, has been associated with higher consumption of fruits and vegetables(Reference Wolfson, Leung and Richardson7–Reference Mills, White and Brown9) and lower consumption of ultra-processed food(Reference Martins, Andrade and Oliveira11–Reference Lam and Adams13), whose consumption is associated with several chronic non-communicable diseases(Reference Monteiro, Cannon and Lawrence14).

As instruments adapted to each sociocultural context, FBDG express the current recommendations for healthy eating worldwide and value the consumption of fresh or minimally processed foods(3–6) that require culinary preparation before consumption. This article investigated whether the FBDG available in the global online repository of the FAO of the UN(15) address recommendations on cooking in their key messages.

Materials and methods

All FBDG available for download from the FAO’s global online repository of FBDG(15) on 2 August 2021 were accessed. The FAO’s repository, the largest available worldwide, publishes only FBDG that are endorsed by a governmental entity. The website includes a page for each country that has contributed materials(15). The following FBDG were included in the analysis: (a) downloadable at the FAO website or found through direct links at the FAO website; (b) target audience was the general population; and (c) written in English, Spanish, French, Romanian, Italian or Portuguese to leverage the linguistic competences of the authors.

For data extraction, we examined key messages to identify any that were explicitly related to cooking, including elements such as the selection, hygiene and preparation of food(Reference Short16,Reference Oliveira and Castro17) and messages about valuing cooking. Data were analysed inductively using thematic analysis(Reference Minayo18,Reference Braun and Clarke19) . The first author read all messages multiple times to familiarise herself with the data. A list of initial descriptive codes and messages representative of each code was generated. The researchers reviewed and discussed the initial codes, and a final list of codes was agreed upon. Each document was analysed by two researchers independently. The coded content was organised into a table and reviewed, and then the themes were identified. A third assessment was made when there was a divergence in the extracted content (10 % of cases). The messages were grouped into three themes: (i) ‘food hygiene’, for messages about good food handling practices; (ii) ‘healthy food preparation’, where the use or the restriction of some ingredients, foods or cooking techniques are encouraged; and (iii) ‘promotion of culinary practices’, in which food preparation is encouraged. Messages from each theme are presented in absolute and relative frequencies. The descriptive results are presented according to the region and country of origin, year of publication and culinary content covered in the key messages. The findings were interpreted from the perspective of health promotion(1–3).

Results

Of the total FBDG available on the FAO website (n 95) distributed in six regions (Africa, n 7; Asia and the Pacific, n 18; Europe, n 33; Latin America and the Caribbean, n 29; Near East, n 6; and North America, n 2), twenty-two were excluded (Asia and the Pacific, n 5; Near East, n 2; Europe, n 15), because the language of the document was different from those selected for analysis. This resulted in seventy-three FBDG analysed. More than half (n 39; 53·4 %) of them included at least one recommendation about cooking in their key messages.

The Latin American and Caribbean FBDG presented the greatest amount and variety of content about cooking in the key messages (eighteen of twenty-nine highlighted the theme). The Near East and North America were the regions with less emphasis on cooking (four of the thirty-nine FBDG). While Venezuela was the country with the oldest document (1991) that incorporated cooking recommendations in its key messages, the most recent documents that included the theme were from Poland and Ecuador, published in 2020(15). El Salvador (2012)(20) and New Zealand (2020)(21) were the countries that presented relatively more messages about cooking (three key messages out of nine and two in six, respectively).

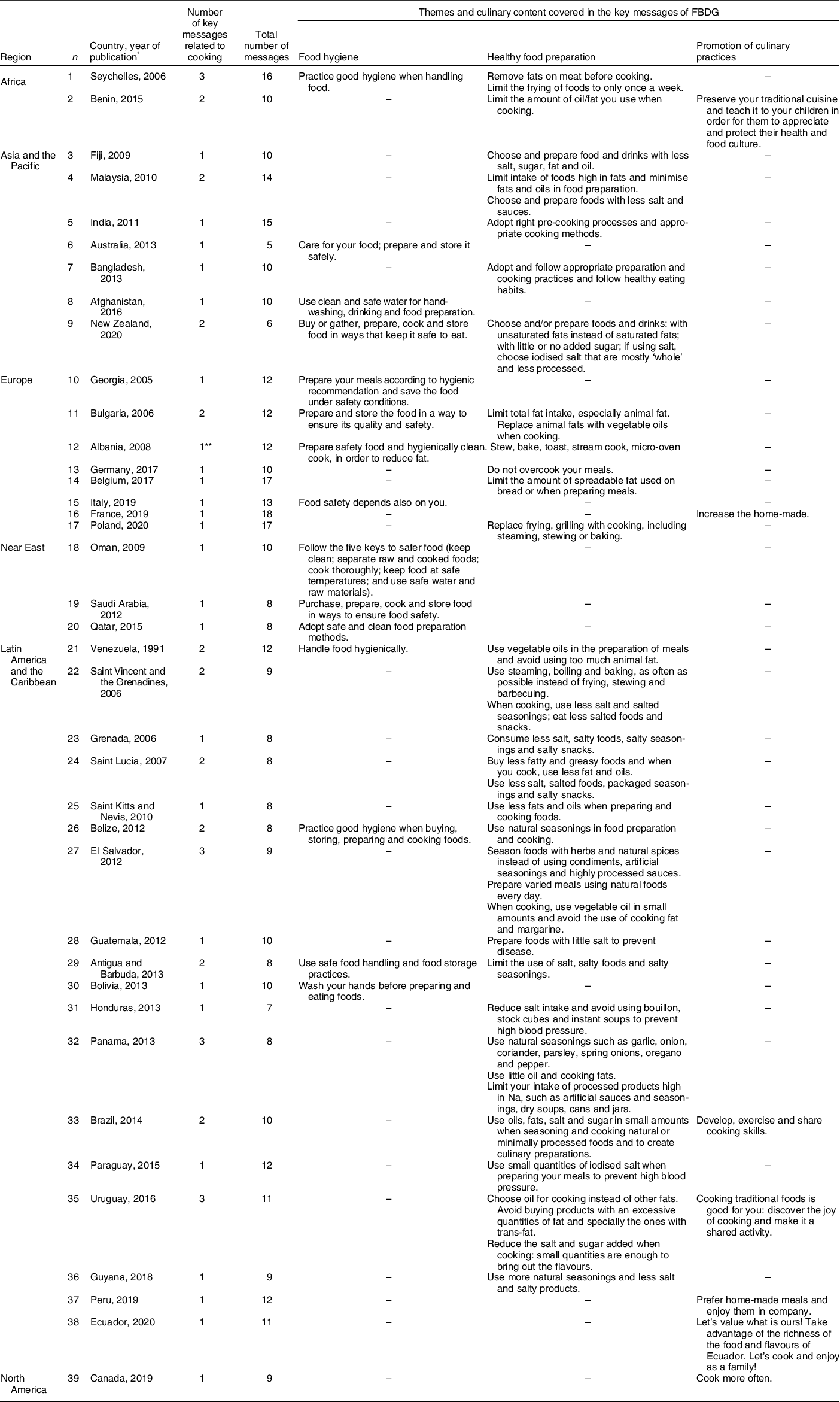

Figure 1 summarises the information about the FBDG analysed according to country and year of publication. Table 1 presents the frequency of key messages and lists the culinary content of each message according to the identified themes.

Fig. 1 Approaches to cooking present in the key messages of thirty-nine food-based dietary guidelines including culinary content according to the region of the world and year of publication

Table 1 Culinary content identified in key messages of the food-based dietary guidelines (FBDG) according to the regions and countries of origin. FAO global online repository, 2021

* All FBDG are available on the FAO’s global repository website: https://www.fao.org/nutrition/education/food-dietary-guidelines.

** On Albania’s FBDG, a key message covers two categories: food hygiene (‘Prepare safety food and hygienically clean’) and healthy food preparation (‘Stew, bake, toast, stream cook, micro-oven cook, in order to reduce fat’).

In general, the recommendations presented in key messages were of a qualitative nature (no quantitative recommendations, such as food portions). Some were imprecise, such as ‘Adopt appropriate pre cooking processes and appropriate cooking methods’, while other messages were more direct, such as ‘Prepare a variety of foods daily using natural foods’. The culinary contents most frequently presented in FBDG were those related to ‘healthy food preparation’ (n 35; 61·4 % of the fifty-seven culinary key messages identified), especially those with warnings about limiting the use of salt and/or fat (mainly those of animal origin, such as milk fats, butter and rendered fats) and the promotion of the use of natural herbs and seasonings (such as aromatic herbs and condiments). In the theme ‘food hygiene’ (n 14; 24·6 %), the most recurrent recommendation referred to the general care necessary for the safe preparation of food, such as keeping the kitchen clean and paying attention to conditions for shopping, food storage, and handwashing. Key messages regarding the ‘promotion of culinary practices’ theme, which value cooking as a sociocultural practice, were the least frequent (n 7; 12·3 %) and were identified only in dietary guidelines published from 2014 onwards. Albania’s key message covered two themes: food hygiene and healthy food preparation (n 1; 1·8 %).

Discussion

Although FBDG are the main instruments that express the recommendations for healthy eating worldwide(1,2) and most of these recommendations include foods that require preparation/cooking before consumption(3–6), just over half (53·4 %) of the seventy-three FBDG analysed included content on cooking among their key messages. When included, the most frequent recommendations related to cooking were those with restrictive content that focused on limiting the use of fat and/or salt during food preparation or those referring to safe food preparation, such as the proper storage of food. On the other hand, in recent years, seven countries (Brazil(22), Benin(23), Uruguay(24), Ecuador(25), Peru(Reference Serrano and Curi26), France(27) and Canada(28)) have emphasised key messages in the promotion of culinary practices in their FBDG, four of which explicitly relate this practice to sociocultural aspects.

The development, practice and sharing of culinary skills have been associated with the consumption of diets with better nutritional quality(Reference Lavelle, Spence and Hollywood29–Reference McGowan, Caraher and Raats31), including a lower consumption of ultra-processed foods in the home environment(Reference Martins, Andrade and Oliveira11–Reference Lam and Adams13). The dietary guidelines for the Brazilian population(22), published in 2014, was the first FBDG to include guidelines to encourage cooking. It presented a broader and less technical perspective that encouraged the improvement of culinary skills, the division of tasks in the kitchen and the transmission of culinary knowledge between generations. After that publication, Benin(23), Uruguay(24), Ecuador(25), Peru(Reference Serrano and Curi26), France(27) and Canada(28) also adopted similar approaches.

France(27) and Canada(28) encourage people to cook more frequently through the messages ‘Augmenter le fait Maison’ and ‘Cook more often’, respectively. This incentive to cook is opportune since the greater the frequency of cooking at home(Reference Wolfson, Leung and Richardson7) and the consumption of home-cooked meals(Reference Mills, Brown and Wrieden10), the better the quality of the diet consumed. However, information on what kind of food to prefer for cooking is equally relevant as the sales and consumption of ultra-processed foods are increasing worldwide(Reference Baker, Machado and Santos32). El Salvador’s dietary guidelines(20) contain a recommendation that considers both pieces of information: ‘Prepare a variety of meals daily using natural foods’. This message is aligned with cooking from scratch, a type of cooking based on the preparation of fresh or minimally processed foods, which is recognised as a way of healthier cooking(Reference Martins, Andrade and Oliveira11,Reference Lavelle, McGowan and Spence33) .

When considering the health benefits of culinary practices, the approaches are diverse. The key messages related to ‘healthy food preparation’ are in line with the WHO healthy diet recommendations(6) and with culinary practices that prevent chronic non-communicable diseases related to unhealthy diets(Reference Raber, Chandra and Upadhyaya34), such as obesity, hypertension and diabetes(Reference Swinburn, Kraak and Allender35). Thus, encouraging healthy culinary practices, that is, those related to the preparation of meals based mostly on fresh or minimally processed foods(22) and prepared with frequent use of natural herbs and seasonings and moderate use of salt, oils, fats, sugars, and fried foods(Reference Raber, Chandra and Upadhyaya34), consists of promoting ‘healthy diets’(6) and, consequently, can potentially contribute to the control and reduction of non-communicable diseases(Reference Raber, Chandra and Upadhyaya34). Although key messages about ‘food hygiene’ are less frequent among more recent documents, diseases caused by the consumption of contaminated food and/or water are still a reality around the world(36), justifying their maintenance in the documents.

Among all FBDG analysed, only the Uruguayan FBDG(24) highlighted cooking as a pleasurable practice(Reference Farmer and Cotter37), thus valuing and considering the expanded concept of health(38). Another issue that is overlooked by documents that promote the practice of cooking is the importance of sharing household tasks (including those related to cooking) and addressing gender issues. The sharing of tasks related to cooking between genders – including men and boys, who usually have less responsibility for this task(Reference Mills, White and Brown9,Reference Wolfson, Ishikawa and Hosokawa39) – is a way to promote healthy eating recommendations based on foods that require preparation/cooking before consumption without overloading women (either older or younger). It is concerning that only two (Brazil(22) and Uruguay(24)) of the seventy-three FBDG analysed presented messages about the importance of sharing activities related to cooking. Additionally, the Ecuador dietary guidelines(25) raise awareness of the importance of ‘cooking with the family’, and Benin’s dietary guidelines(23) recommend the transmission of culinary knowledge to children as a way to promote health and maintain the country’s food culture; these benefits have been observed in recent studies(Reference Martins, Andrade and Oliveira11,Reference Lavelle, Spence and Hollywood29,Reference Martins, Machado and Louzada40) .

This study provides the first analysis of culinary content in key messages of FBDG and highlights the importance of giving visibility to the promotion of cooking in FBDG as a strategy for public policy-makers to develop actions that simultaneously promote the health of people and the planet. The fact that messages encouraging culinary practices seem to be gaining attention in the most recent FBDG is a positive indicator that cooking is considered an essential practice for promoting healthy eating. However, it can also be an alert that, as an example of the culinary skills transition process seen in the British reality(Reference Lang and Caraher41), other populations around the world may be changing their relationship with domestic cuisines and encouraging a growing number of orientations that promote cooking. On the other hand, the absence of key messages regarding sustainable cooking practices is also an important indicator that this subject is not considered strategic to mitigate climate impacts – a position different from that indicated by recent scientific evidence(Reference Frankowska, Rivera and Bridle42–44).

Despite the strengths of this study, its results need to be interpreted considering its limitations. A limitation of this study is the fact that only FBDG available in the FAO repository(15) were included in our analyses; however, to the best of our knowledge, this is the largest database on dietary guidelines in the world(2). Another limitation of this study was the omission of 30·1 % (n 22) of the documents made available by the FAO’s repository(15) because they were written in languages not chosen for analysis in this study.

Conclusion

Cooking is a practice developed by individuals in the home environment, and there is growing evidence that it is related to improvements in individuals’ and populations’ food consumption(Reference Mills, White and Brown9,Reference Martins, Andrade and Oliveira11,Reference Lam and Adams13,Reference McGowan, Caraher and Raats31,Reference Frankowska, Rivera and Bridle42,44) . In addition, it is considered a strategy to facilitate the implementation of healthy and sustainable diets; thus, cooking should be encouraged, promoted and supported by public policies, including FBDG. The good news is that several of the FBDG already present culinary content in their key messages. Nevertheless, this subject needs more visibility and should be presented more broadly in official documents that guide healthy eating, such as the FBDG, whose purpose is to assist the general population in following food, nutrition and related health recommendations(45).

Acknowledgements

Financial support: This study was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior – Brasil (CAPES) – Finance Code 001 and had the support of the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (FAPERJ) (process numbers E-26/210.064/2021). Authorship: M.F.B.O. and I.R.R.C. were responsible for the conception and design of the study; all authors developed the data collection and analysis; M.F.B.O. wrote the original draft of the manuscript; I.R.R.C. and C.A.M. contributed to writing the manuscript and revised each draft; I.R.R.C. was the study supervisor. All authors have read and agreed to the final version of the manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: This work did not involve human subjects or ethical approval.

Conflicts of interest:

There are no conflicts of interest.