Social scientists are increasingly making a case for sport to be studied with greater scrutiny, as it is ‘a vast global field of social, cultural, economic and political activity which cannot be ignored’( Reference Giulianotti 1 ). Public health has come later to consider the relationship between sport and its communities, and there is now a growing literature examining the relationship between sports clubs, their stadia and health( Reference Parnell, Curran and Philpott 2 ). From a commercial perspective, the ability of sports clubs to harness their badge/brand to engage fans is almost unique( Reference Parnell, Pringle and McKenna 3 ). Sport can provide a sense of community and belonging, and support can be lifelong( Reference Crawford 4 ). Thus, it is unsurprising that commercial organisations often choose to use sport to market their products and develop their own brands. Clubs can provide access to audiences that are large, potentially receptive and relatively stable over time. From a public health nutrition perspective, some of these products are damaging to health. In 2006, the Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA) World Cup had official partners of Budweiser beer, McDonald’s and Coca-Cola( Reference Collin and MacKenzie 5 ). In 2012, the London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games were again sponsored by Coca-Cola and McDonald’s, with confectionery brand Cadbury also involved as a ‘tier two’ sponsor, the sole supplier of chocolate and ice cream at the Games( Reference Cade, Curran and Fuller 6 ). The link between the sugar industry and the Olympics has received international criticism from public health advocates( Reference Hinds 7 ).

Mega events such as the Football World Cup and the Olympic Games are always likely to receive increased attention partly because of the huge audiences developed through global sports television broadcasting contracts worth millions of dollars( Reference Evens, Iosifidis and Smith 8 ). Professional sports clubs also have large followings, with football clubs such as Real Madrid and Manchester United having 105 million and 74 million followers on Facebook( 9 ) for example. Thus, sports themselves and traditional sponsorship practices are under increased scrutiny( Reference Garde and Rigby 10 ) and there is more understanding of how commercial organisations may use sports settings to target both children and adults. Studies have been undertaken across sports in a number of countries, including an examination of national and regional sporting organisations in New Zealand( Reference Carter, Signal and Edwards 11 ). That study found that where additional marketing activities were used to create repeat exposure for brands, these often targeted children. An international study across seven countries in Europe and Australasia in 2016 showed a positive association between exposure to alcohol sports sponsorship and alcohol consumption( Reference Brown 12 ). We know that food advertising on television impacts on children in particular and may negatively affect their snacking habits( Reference Norman, Kelly and McMahon 13 ).

When companies selling unhealthy products sponsor children’s sport, the concern may be even greater( Reference Macniven, Kelly and King 14 – Reference Kelly, Baur and Bauman 16 ). In a review of the evidence presented to the WHO in 2006, it was shown that food and drink companies systematically target children, marketing chocolate, sweets, soft drinks and other foods high in fat, sugar and salt. This kind of food promotion has been shown to influence children’s consumption and other diet-related behaviours and outcomes( Reference Hastings, McDermott and Angus 17 ).

Many fast-food franchises use sport sponsorship to penetrate their local markets( Reference Cousens and Slack 18 ). Thus, children’s frequent participation in organised sport exposes them to high levels of food and beverage sponsorship promotions( Reference Kelly, Baur and Bauman 19 , Reference Kelly, Bauman and Baur 20 ). This exposure in turn may influence their consumption of foods and beverages based on positive attitudes towards sport sponsors. Kelly et al.( Reference Kelly, Baur and Bauman 21 ) found junior sports players in Australia believed ‘food company sponsors are kind, generous and cool’.

As public health concerns around children’s health grow, and while childhood obesity continues to increase worldwide, advocates believe that fundamental changes will be required across the social and economic environment if we are to combat the rise in overweight and obesity, with the high consumption of unhealthy foods seen as the greatest culprit( Reference Ebbeling, Pawlak and Ludwig 22 ). While mega events have received attention, professional sports clubs, sometimes huge commercial brands with an ability to influence millions of fans globally, are not widely considered by public health despite their gatekeeping role in enabling brand sponsors to reach unparalleled audiences. For public health to influence the sponsorship choices and commercial arrangements that professional sport clubs choose to make, we need to understand the scale of the issue.

The present scoping review was undertaken to identify how much is known about the relationship between professional sports clubs and food and beverage companies. In doing this, we sought to identify where the gaps may lie in our knowledge and highlight the need for any further research that may be required.

Methods

As this is an emerging area of academic interest, we anticipated the possibility that we would identify few relevant studies. In developing the scoping review, we followed the framework proposed by Arksey and O’Malley( Reference Arksey and O’Malley 23 ).

Search strategy

In agreeing a search strategy, we used our existing knowledge of relevant literature and keywords identified for specific papers. We discussed the strategy with colleagues, took an iterative approach for agreeing key concepts and words, and achieved a consensus before engaging in searches.

We agreed no restrictions on geography, age groups or gender. We searched for English-language publications only, for practical reasons. Given our focus on professional sports clubs, we excluded individual sportsmen and sportswomen from our search, together with amateur or community clubs and national teams or sports governing bodies. We also excluded mega events such as the Olympics because of the attention already given to these events. Finally, we were aware that there is a growing literature around alcohol which has already received some attention on its association with sport and so excluded this from our review( Reference Brown 12 ).

Keywords used for our search are shown in Table 1. We used four concepts to exploring the relationships between Big Food corporations and professional sports clubs: ‘Professional Sports Clubs’, ‘Food and Drink’, ‘Marketing’ and ‘Health Impacts’. For each concept, we identified a ‘what’. Thus, in the focus on ‘Professional Sports Clubs’ we used search terms such as ‘sports grounds’, ‘football’, American football’ and other popular sports; in ‘Food and Drink’, we searched for ‘processed food’, ‘sweet products’ and similar. The ‘who’ (i.e. the consumer or fan/supporter) remained consistent as they are the target audience of the Big Food corporations in their relationships with professional sports clubs.

Table 1 Keywords used in the search for studies to include in the present scoping review on the relationship between Big Food and professional sports clubs

Regarding ‘Health Impacts’, the ‘what’ included the major non-communicable diseases (which may be influenced negatively through the marketing of ‘unhealthy’ foods and drinks). ‘Food and Drink’ was more complicated, but we agreed common terms for fast foods and processed foods, and included the names of major producers, Coca-Cola (Coke), Kentucky Fried Chicken (KFC), McDonald’s and PepsiCo (Pepsi), because of their known longstanding associations with sports sponsorship. In ‘Marketing’, we included words describing the various methods generally employed to market foods and drinks. Finally, we identified both ‘clubs’ to search for, but also the names of the largest team-based professional sports in the English-speaking world (e.g. football in the UK, American football in North America and rugby in Australia).

We searched six databases to identify relevant papers: CINALH Plus, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, PubMed, SportDISCUS and Web of Science. Boolean operators were used as illustrated in Table 1. We combined each block using ‘AND’. After initial trial searches, two authors discussed and refined the search terms which were finalised as in Table 1. In addition, we used test papers to ensure our search correctly identified the relevant and appropriate research papers.

Literature selection and data synthesis

The lead author carried out the first search and reviewed the titles generated. Two authors then undertook an abstract review before agreeing the papers for full review. All authors participated in the process of reading and reviewing the twenty-six papers considered at this stage of the process. Discrepancies were discussed by all three authors before agreeing the final six papers to be included in the scoping review. The reference lists of included papers were searched by hand for additional references that might fit the inclusion criteria.

Consulted experts suggested eleven papers to consider but none met the inclusion criteria described. Of these, ten were drawn from marketing literature around North American professional sport, but while their titles sounded appropriate, once examined, none made links between professional sports clubs and Big Food. The final paper excluded from the eleven was Australian in origin and was considered( Reference Kelly, Baur and Bauman 24 ). However, although relevant to discussions concerning sports sponsorship and examining views around this sponsorship, the paper was excluded as it was about ‘elite and children’s sports’ rather than professional sports clubs.

We anticipated that potentially there could be substantial variety in the types of study design and data available in relevant papers. With this is mind, we aimed to synthesise studies thematically, by country or study design, depending on what was most appropriate after all studies had been identified. When a review includes different study designs, established tools for assessing risk of bias or methodological quality are not appropriate. We therefore used a scoping review to address our aim and to enable us to see as wide a breadth of the relevant literature as possible.

Results

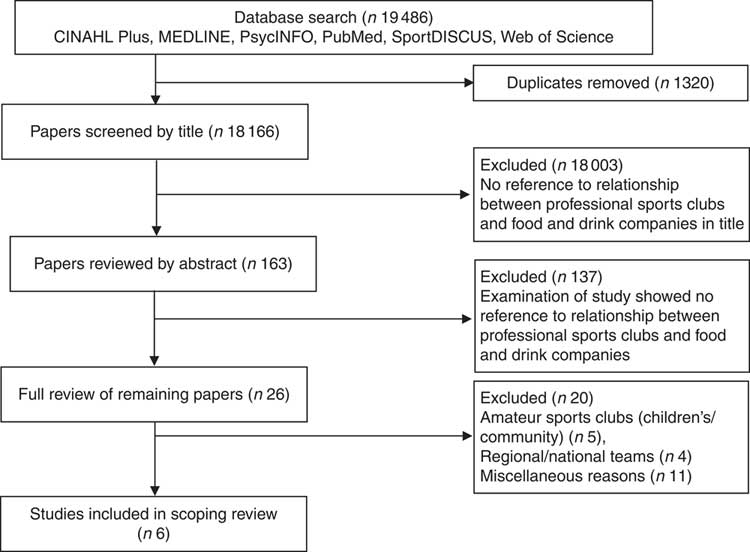

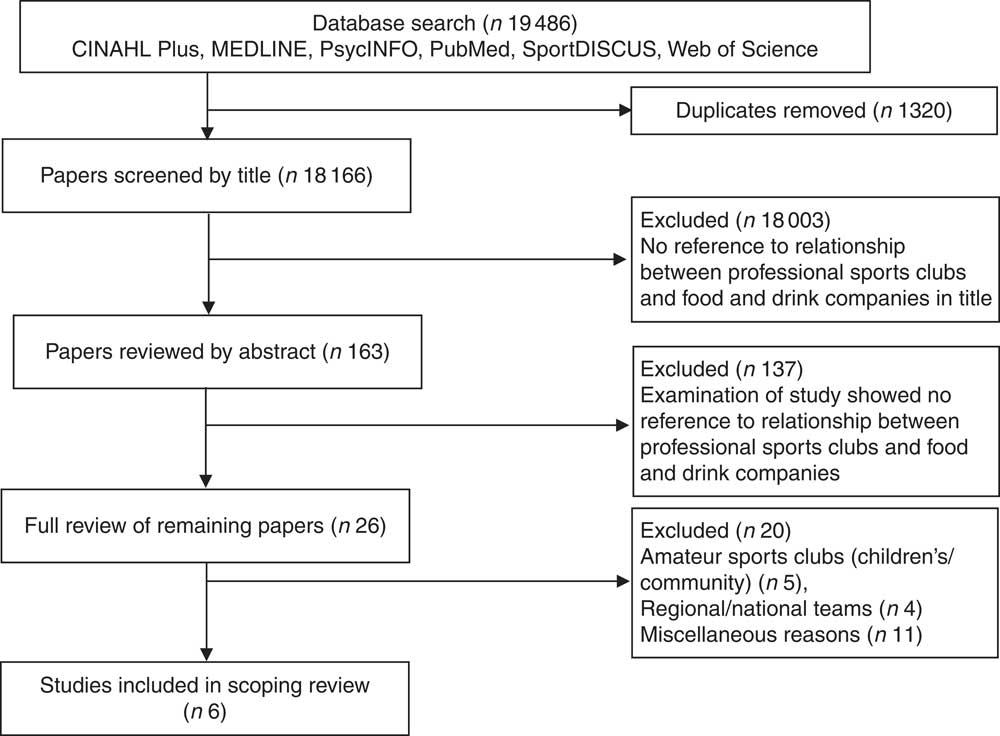

Figure 1 details the process described in the previous section and the results obtained at each stage. The database searches generated 19 486 items including papers. A further eleven papers were suggested by experts working in the area of public health and sport. The final number of items included in the search was 18 166 after duplicates were removed. The lead author then reviewed the titles of all 18 166 and retained 163 papers for abstract review. One hundred and thirty-seven papers were excluded at this stage because although sport and food or sponsorship were often indicated in titles, abstracts indicated that professional sports clubs were not included in their remit. Two authors then undertook the abstract review before agreeing twenty-six academic papers for full-text review. Of the twenty-six papers selected for review, fourteen originated from Australia and New Zealand. Twenty publications were excluded as they did not meet the inclusion criteria detailed above. These were excluded for a wide number of reasons, with the most common being that the article focused more on aspects of commercial sponsorship of sport in general, rather than professional clubs.

Fig. 1 Flowchart showing the search for studies to include in the present scoping review on the relationship between Big Food and professional sports clubs, and the results obtained at each stage

The twenty papers excluded during full-text review received careful scrutiny. The studies from Australia and New Zealand were particularly relevant to the wider discussion around sport and health, and suggested that the food and drink industry targets its sponsorship to children’s sport within the community. The organisation of Australian sport reflects the federal system of government and includes national and state sporting organisations who are represented as peak or umbrella organisations. These peak organisations have received attention in Australian academic literature because of the media attention they generate and the consequent attention they receive from commercial sponsors. However, as regional bodies, they fall outside the remit of the current scoping review.

Characteristics of included studies

Table 2 lists the six papers that were included in the review showing their authors, study design, study countries of interest and main results. As is common in scoping reviews, study designs varied substantially. Two studies had an experimental design( Reference Bestman, Thomas and Randle 25 , Reference Pettigrew, Rosenberg and Ferguson 26 ). Other study designs were a systematic review( Reference Carter, Edwards and Signal 27 ), a case study( Reference Jensen, Weston and Wang 28 ), a content analysis( Reference Sherriff, Griffiths and Daube 29 ) and a survey of professional football team shirt sponsors( Reference Unlucan 30 ). Three studies contained data from Australia( Reference Bestman, Thomas and Randle 25 , Reference Pettigrew, Rosenberg and Ferguson 26 , Reference Sherriff, Griffiths and Daube 29 ), one from the USA and Austria( Reference Jensen, Weston and Wang 28 ), and two had a worldwide scope( Reference Carter, Edwards and Signal 27 , Reference Unlucan 30 ). Sports examined included football (soccer)( Reference Jensen, Weston and Wang 28 , Reference Unlucan 30 ), rugby league( Reference Bestman, Thomas and Randle 25 ) and union( Reference Pettigrew, Rosenberg and Ferguson 26 ), Australian football( Reference Bestman, Thomas and Randle 25 , Reference Pettigrew, Rosenberg and Ferguson 26 ), basketball( Reference Bestman, Thomas and Randle 25 ), netball( Reference Pettigrew, Rosenberg and Ferguson 26 ) and cricket( Reference Bestman, Thomas and Randle 25 – Reference Carter, Edwards and Signal 27 , Reference Sherriff, Griffiths and Daube 29 ).

Table 2 Summary of the papers included in the present scoping review on the relationship between Big Food and professional sports clubs

Five of the six studies examined the possible relationship between sports spectators and the advertising and sponsorship that they may be exposed to in stadia or through watching broadcasts( Reference Bestman, Thomas and Randle 25 – Reference Sherriff, Griffiths and Daube 29 ). The final study( Reference Unlucan 30 ), a survey, focused more on the potential scale and value of sports sponsorship in generating income for football clubs, with food and drink sponsorship identified as a product category.

Main findings

Overall, results highlighted the commercial potential of corporate actors from the food and beverage industry engaging with professional sport. Large quantities of money were available to clubs, with food and beverage companies the leading product category of sponsorship( Reference Unlucan 30 ). The potential reach of sponsorship and advertising to sports fans was highlighted, as well as some evidence that young fans had internalised associations between teams and certain brands/products( Reference Bestman, Thomas and Randle 25 , Reference Pettigrew, Rosenberg and Ferguson 26 ). Results also suggested that sponsorship could be lucrative for the clubs involved. A single study highlighted that sponsorship relationships could result in negative reactions from fans( Reference Jensen, Weston and Wang 28 ).

Extent of food and beverage advertising

Unlucan( Reference Unlucan 30 ) classified the main shirt/jersey sponsors in the top (men’s) football leagues of seventy-nine countries. The study highlighted the vast money available to clubs when working with a shirt sponsor, providing examples from a range of European football clubs. For example, Unlucan noted that FC Barcelona earned about £25 million per year from the Qatar Foundation for its shirt sponsorship in 2014–15 (this is dwarfed by the deal announced by Real Madrid with Emirates Airlines in September 2017 for $82 million per year( Reference Ozanian 31 )). When shirt sponsorship was analysed, the sector with the largest number of shirt sponsors (149 from 969 teams; 15 %) was food and beverage companies including alcohol producers. The next most represented industrial classification was travel and leisure companies which included gambling, such as online gambling, online casinos and other betting companies (120 companies; 12 %). The study noted that ‘in some countries laws and regulations do not allow companies in industries like tobacco, gambling and alcohol to sponsor football/soccer clubs’ (p. 51). It was also noted that some companies (such as Pepsi and McDonald’s) sponsor ‘several teams’ (p. 48). The study concluded that in an environment of increasing costs, shirt/jersey sponsorship represented one of the most important revenue sources for football clubs.

Potential reach and fan responses

Jensen et al.’s( Reference Jensen, Weston and Wang 28 ) study suggested that professional clubs must approach sponsorship cautiously. Using a case study methodology, they detailed the negative reaction of fans to the renaming and branding of two football teams, after receiving sponsorship from Red Bull, an energy drink company. The study found opposition to renaming professional football teams after the Red Bull energy drink, and that this opposition came from politicians and civic leaders as well as fans.

The four remaining studies focused on fan exposure, with two studies specifically examining children’s recognition of professional sports club sponsors( Reference Bestman, Thomas and Randle 25 , Reference Pettigrew, Rosenberg and Ferguson 26 ). Data from these studies were collected in Australia. Sherriff et al.( Reference Sherriff, Griffiths and Daube 29 ) analysed sports sponsorship by food and alcohol companies in Australian cricket (in limited-over competition specifically). They considered the proportion of time that the main sponsor’s (Kentucky Fried Chicken) logo was seen during three telecasts, the extent of paid advertising in the telecasts, and also included the associated ground advertising. They suggested sport sponsorship through telecasts was able to saturate family viewing time without any form of regulation. The main sponsor’s logo was visible in some form (including on equipment and clothing) for 44 % of the game time in one telecast and 74 % of the game time in the other.

Pettigrew et al.( Reference Pettigrew, Rosenberg and Ferguson 26 ) used an experimental design with 164 children aged 5–12 years living in Perth, Western Australia to explore children’s implicit associations between popular sports and a range of sports sponsors (ten out of twenty-three of which were for unhealthy foods and beverages). Three-quarters of the children (76 %) were able to align at least one correct sponsor with the relevant sport. Just over half correctly matched an Australian Football League team with its fast-food chain sponsor. In addition, children appeared to associate certain sports with unhealthy foods and beverages in general, even if they did not identify the correct unhealthy food and beverage sponsor.

Bestman et al.( Reference Bestman, Thomas and Randle 25 ) used similar techniques to measure the implicit recall of team sponsorship by 5–12-year-old children. The sponsors (two unhealthy foods) of seven sporting teams were used, covering the sports of rugby league, Australian Football League, basketball and cricket. Of the eighty-five children included in the study, 77 % were able to identify at least one correct shirt sponsor, with 9–12-year-olds significantly more likely to recall sponsors than the younger children. Similar to Pettigrew et al.( Reference Pettigrew, Rosenberg and Ferguson 26 ), associations between sponsorship and teams were identified at both the brand and product level. In addition, teams that were identified as being most liked by children were sponsored by brands selling unhealthy foods.

Carter et al.( Reference Carter, Edwards and Signal 27 ) undertook a systematic review to identify and critically appraise research on food environments in sports settings. They found fourteen English-language studies, of which ten were from Australia and one from New Zealand. Studies included in the review were mainly concerned with junior level and amateur sports clubs, and thus these studies’ findings were not relevant to the present scoping review. A single study (Sherriff et al.( Reference Sherriff, Griffiths and Daube 29 )) was identified as meeting the inclusion criteria for the scope of our review and has been discussed above.

Discussion

The present scoping review found very few papers examining the health-related dimensions of commercial sponsorship of professional sports clubs by food and beverage companies. We therefore can conclude that this is an area that has received little scrutiny from an academic public health perspective.

The six included papers covered a variety of sports and highlighted that sponsorship by brands selling unhealthy products is common, and that this exposure is likely to create an association between clubs and sponsors among fans. As stated above, there appears to have been greater academic examination of sponsorship by brands selling unhealthy foods in Australia. These Australian studies have been particularly concerned about the impact on children and young people of this kind of sponsorship. To develop the understanding of these findings, there is a clear case to be made for undertaking further studies worldwide on the impact of sports sponsorship on buying preferences.

The papers identified related primarily to sports clubs in high-income countries, although Unlucan’s study of football shirt sponsorship covered seventy-nine football leagues. Given this, our review does not reflect the global reach of many sports clubs. The English Premier League (the richest football league in the world) broadcasts in 212 territories attracting approximately 4·7 billion views per season( Reference Cleland 32 ), highlighting that English football clubs’ relationships with junk food and drink brands is likely to influence behaviour beyond the UK, including in low-income countries. Cricket is another sport with a significant global following, including in India and Pakistan. Although no studies were found linking Indian professional sports clubs with Big Food corporations, Silk and Andrews( Reference Silk and Andrews 33 ) describe how Indian cricket and its star performers have been used to promote both Coca-Cola and Pepsi.

It is surprising that advertising and sponsorship by unhealthy foods and beverages in professional sports clubs has largely escaped scrutiny within the academic public health literature, despite commercial determinants of health being added to those originally listed in the Ottawa Charter( 34 ). Kickbusch et al.( Reference Kickbusch, Laverack and Pinto 35 ) argue that in the 21st century, we need to address the interface of the political and commercial determinants of health; in other words, how society and government are affected by powerful transnational companies and their marketing. They wrote that in the mid-1980s we underestimated globalised corporate and marketing power and gave as an example how access to beer was provided at the FIFA World Cup in Brazil at the insistence of the FIFA General Secretary despite this being contrary to Brazilian law. In this example, the commercial clout of sponsorship overrode a state’s law, reflecting the debate globalisation theorists have about the erosion of state power in an era of global capitalism( Reference Strange 36 – Reference Mann 38 ).

Gilmore et al.( Reference Gilmore, Savell and Collin 39 ) discuss how corporations may contribute to the global burden of disease. Food and alcohol companies often use corporate social responsibility to enhance reputation and to promote brands. And it can be argued that sport is a useful vehicle for the marketing of food companies. We have highlighted that more research has been carried out in Australia and New Zealand concerning sport and health than in other countries, and it is argued that the consumption of live sport is mirrored by the consumption of high quantities of ‘meat pies, chips and beer’ in these countries( Reference Parry, Hall and Baxter 40 ). However, researching the commercial determinants of health in sport is still a relatively new area. There is likely to be further scrutiny of shirt sponsorship particularly as individual players( 41 ) and some fans( Reference Sainty 42 ) may object to some industries’ involvement from a wide range of perspectives. Since Jensen et al.( Reference Jensen, Weston and Wang 28 ) published their Red Bull study, the energy drink company has founded a team known as RB Leipzig now playing in the top tier of the German Bundesliga. Both RB Leipzig and Red Bull Salzburg qualified for the Union of European Football Associations (UEFA) Champions League in 2017–18, raising questions about ownership and fair sporting competition( 43 ). RB Leipzig has also raised concerns from German football fans who dismiss them as a ‘plastic club’ whose purpose is to help sell fizzy drinks( Reference Shotter 44 ). Crompton( Reference Crompton 45 ) highlights that the primary source of reputational risk for a commercial sponsor in sport (such as Red Bull) may be the ‘increased public sensitivity to the negative health impacts of some product categories, most prominently those of tobacco, alcohol, gambling and products that are high in fat, salt or sugar’ (p. 420).

Professional football shirt sponsorship by the gambling and online betting and casino industry has received attention recently( Reference Bunn, Ireland and Minton 46 , Reference Lopez-Gonzalez and Griffiths 47 ) and this has become a political issue, with the British Labour Party promising to end gambling industry shirt sponsorship should it form the next government( Reference Davis 48 ). Just as ethical debate about the appropriateness of sponsorship is being applied to mega events and whether policies can be applied to provide healthier environments( Reference Piggin, Tlili and Louzada 49 ), this scrutiny is likely to be applied to individual professional clubs and leagues in the future.

The evidence of how food and drink and alcohol marketing through sponsorship of community and professional sport in Australia may influence children’s food and drink choices has also led to advocacy from charities wanting government action on this type of marketing and new approaches to sport sponsorship( 50 ). Spectators at sporting events often cannot understand why healthier foods are not promoted when players themselves are portrayed role models for health( Reference Ireland and Watkins 51 ). There is certainly a case for public health advocacy to address and champion the public good when food corporations use commercial levers to promote products which may be harmful to human health( Reference Brinsden and Lang 52 ), even if care may need to be taken in the approach to this advocacy( Reference Smith and Stewart 53 ).

The current scoping study considered food and drink sponsorship of professional sports clubs. There are wider concerns in the public health community about how food companies build brand images and target parents and children( Reference Richards, Thomas and Randle 54 , Reference Speers, Harris and Schwartz 55 ) through corporate social responsibility initiatives. This scrutiny is likely to apply to sport and the appropriateness of alcohol, gambling and food and drink sport sponsorship( Reference Danylchuk and MacIntosh 56 ).

Strengths and limitations

The strength of the present study is that it has highlighted that the examination of food and beverage sponsorship in professional sport is an under-researched area. By using a scoping review design, we were able to accommodate a range of study designs and data into our synthesis. The search strategy was comprehensive, and we believe that we captured the relevant academic literature.

A potential study weakness was that the databases we searched are primarily concerned with evidence-based peer-reviewed papers and therefore it is possible that relevant articles in the grey literature may have been missed. Only English-language sources were retrieved and reviewed, which was also a limitation. Although the scoping review design allowed us to be inclusive in terms of including a wide variety of study types, it was challenging to synthesise such disparate studies. A study such as Jensen et al.( Reference Jensen, Weston and Wang 28 ) used a case study approach, with relatively unclear methods, and therefore it was difficult to assess the extent to which this could be considered a research study. In addition, the other studies of fan exposure( Reference Bestman, Thomas and Randle 25 , Reference Pettigrew, Rosenberg and Ferguson 26 , Reference Sherriff, Griffiths and Daube 29 ) were relatively small scale, with limited generalisability.

A further limitation is that due to the heterogeneity of the included studies, we could not conduct a risk of bias assessment of the included studies. Finally, we considered professional sports clubs only in the present study. Individual ‘celebrity’ sportsmen and sportswomen are used to endorse a wide range of products to influence consumption( Reference Cashmore 57 ) and this deserves further study.

Conclusions

Given the prominence sport plays in international cultures, it can provide corporations with an unparalleled opportunity to promote their brands and products on a global stage. It is no surprise that some of the wealthiest food and drink companies will use this reach by trading on the relationships and status in the community that professional sports clubs often possess. The present scoping review demonstrates that there is only a very limited evidence base in this field. If advocates are to address the commercial determinants of health in sport, a wider body of evidence will be required to convince others of the potential of unhealthy food and beverage sponsorship to impact negatively on health. As has been described, fans themselves have a view on ‘their’ clubs and the brand relationship between supporters and clubs is complex. More studies that reveal how food and drink marketers work, and the audiences they carefully select, will lead to a wider discussion about the ethics of sport sponsorship, whether the sponsor is a fast-food company, a gambling corporation or an alcohol product. This discussion is likely to include a debate about regulation and legislation by sports leagues, governing bodies of sport and by government, particularly when the audience of most sports includes children and young people. More comprehensive studies on the relationship between commercial corporations and sport are therefore urgently required.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors thank Dr Matthew Philpott for his contributions to early discussions about the focus of the paper and the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments. Financial support: This work was supported by the University of Glasgow, College of Social Sciences. S.C. is funded by the Medical Research Council and the Chief Scientist Office (Scotland) (Medical Research Council Strategic Award MC_PC_13027; Medical Research Council grant numbers MC_UU_12017/12 and MC_UU_12017/14); and the Chief Scientist Office of the Scottish Government Health Directorates (grant numbers SPHSU12 and SPHSU14). The funding agencies had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interests. Authorship: The paper was conceived jointly. Database searches were undertaken by R.I., supported by C.B. and S.C. Sifting of references was led by R.I. with support from S.C. R.I. first-drafted the manuscript and S.C. and C.B. contributed to redrafting. Ethics of human subject participation: Not applicable.