In accordance with a growing interest in workplace well-being, the number of interventions in this field has increased over recent years. Researchers aim to identify the most effective strategies for workplaces to encourage staff to live healthier lifestyles (e.g. facilitate healthy eating at work, provide facilities to exercise more frequently and/or offer services to quit smoking). Numerous studies of diet, physical activity, weight loss and/or smoking behaviour change interventions in the workplace setting are published annually, to assess the impact of such interventions on health-, diet- and ultimately economic-related (i.e. work-related) outcomes. Simultaneously, the number of reviews, systematic reviews (SR) and meta-analyses (MA) summarising these interventions is increasing, attempting to synthesise the wealth of published evidence and to inform future intervention designs as well as guide policy makers.

Few SR highlight findings from solely dietary interventions( Reference Geaney, Kelly and Greiner 1 – Reference Pomerleau, Lock and Knai 5 ). Therefore, it proves challenging to filter out intervention components successful in changing dietary behaviour as part of a workplace well-being project. To learn from previous research and implement diet behaviour change interventions likely to be most effective, relevant literature on dietary workplace interventions needs to be reviewed. When turning to SR, it needs to be considered that new guidelines on how to conduct and report SR have been introduced since the first SR were conducted( Reference Moher, Liberati and Tetzlaff 6 , Reference Shea, Grimshaw and Wells 7 ). Hence, SR are likely to differ in their reporting structure and quality. Therefore, the aims of the current SR of SR was to: (i) summarise the findings of published SR reviewing either dietary interventions or multicomponent lifestyle interventions that distinctively report dietary intervention components and their effects on diet, health- and economic-related outcomes in the workplace setting; (ii) assess the most effective intervention components; and (iii) assess the quality of the SR.

Methods

A systematic search was carried out following a predefined search protocol in accordance with the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines( Reference Moher, Liberati and Tetzlaff 6 ).

Inclusion criteria

SR and MA had to meet the following criteria: (i) be published in a peer-reviewed journal before August 2017; (ii) review interventions based in the workplace setting; (iii) be published in the English language; (iv) include adults aged ≥18 years; (v) clearly describe dietary intervention components or clearly describe the impact of a multicomponent intervention on diet-related outcomes; (vi) describe the effect of dietary intervention components on dietary behaviour-related outcomes (i.e. intake, knowledge, attitude, skills), health-related outcomes (i.e. weight, BMI, waist circumference, blood pressure, blood lipids, fasting blood glucose) or economic-related outcomes (i.e. absenteeism, sick leave, productivity, return on investment); and (vii) include the general population and/or ‘at risk’ groups. Narrative reviews, reports and position statement were excluded from the analysis.

Search strategy

The search strategy was developed in Embase and was then adapted for the following databases: MEDLINE, CINAHL, Web of Science, Cochrane Library and Google Scholar (see online supplementary material, Supplemental Fig. 1). In addition, relevant studies were identified in Zetoc and NHS Evidence, and reference lists were hand-searched to identify studies that were not detected through the database search. The search was conducted in December 2014 and was updated in August 2017. Abstracts and full texts were reviewed independently, by two reviewers (D.S. and J.V.W.), for inclusion in the current SR of SR. Any disagreement between reviewers was solved by discussion until an agreement was reached.

Data extraction

The first reviewer (D.S.) extracted all outcomes under review into a structured template which was then reviewed by the second reviewer (J.V.W.) for completeness. Any discrepancies between reviewers were discussed and resolved. All results were condensed and reported as extracted from the original research paper. Where information from the primary studies was not summarised in the SR, the researchers reported the findings as stated in the SR and did not refer back to the primary studies.

Quality assessment

The AMSTAR (‘assessment of multiple systematic reviews’) quality criteria tool has been recommended as the only validated tool for quality assessment of reviews( Reference Shea, Grimshaw and Wells 7 ) and was used to assess the quality of identified SR. The AMSTAR criteria tool ranks SR on eleven quality items. The SR quality rating was conducted by the two reviewers independently and any disagreements were discussed until consensus was reached.

Data synthesis

The heterogeneity in reporting among studies under review did not allow for a statistical analysis in form of a MA to be conducted. Instead, the reviewers conducted a narrative synthesis and systematically extracted the results for each outcome under review addressed in the SR and MA.

Results

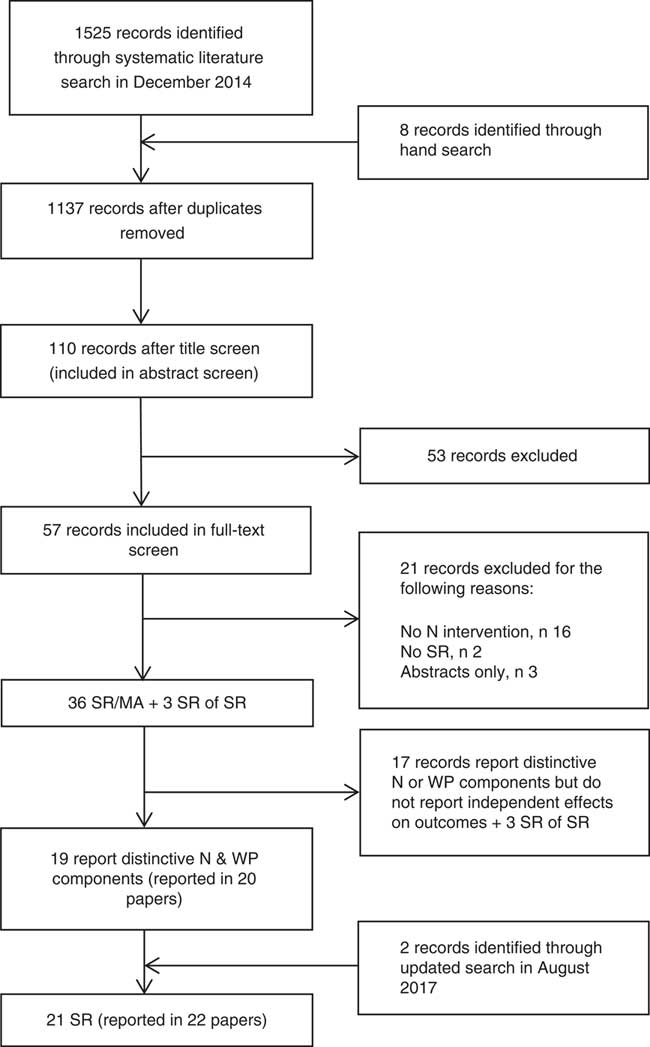

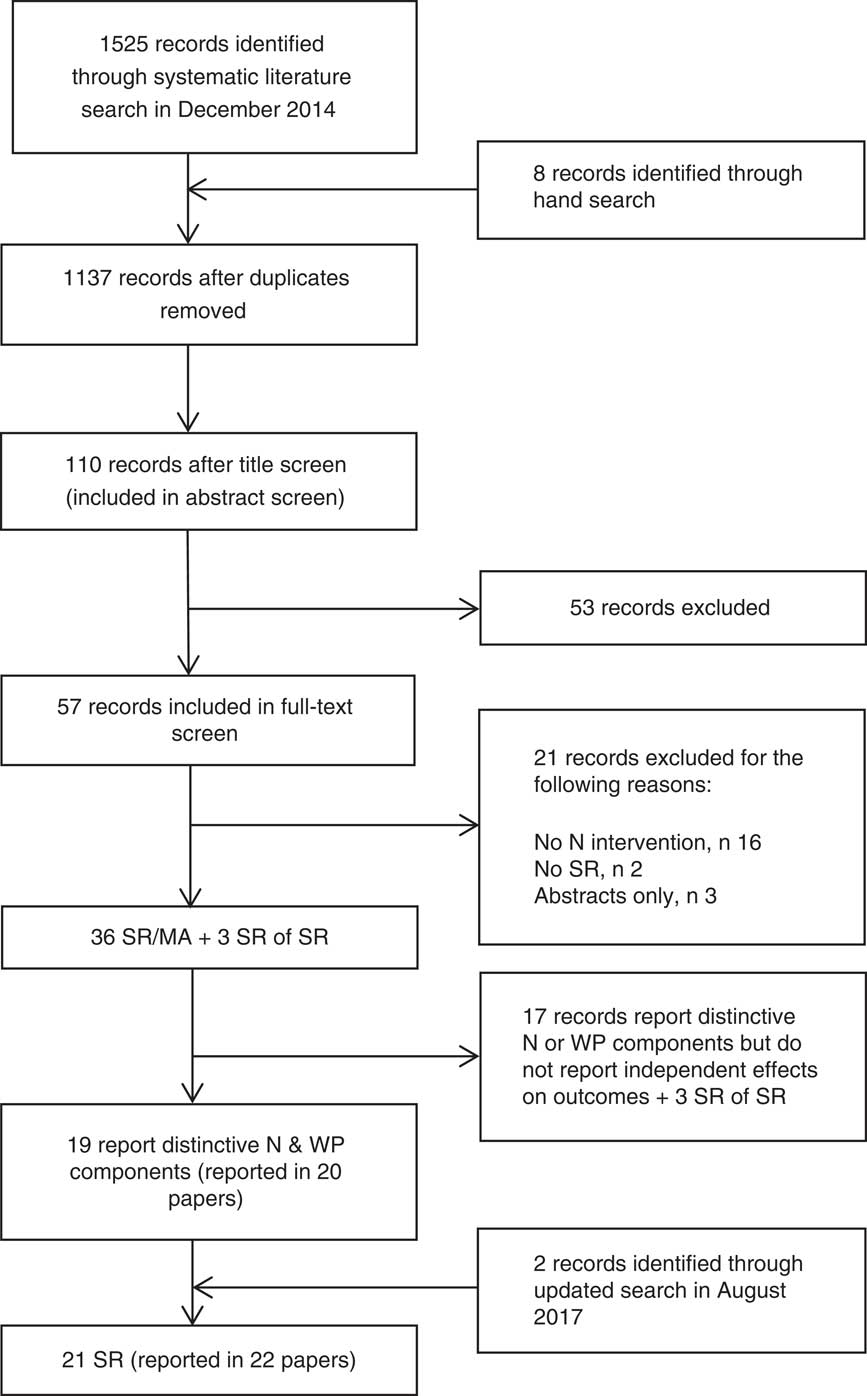

The search generated 1137 potential articles after duplicates were removed (Fig. 1), of which thirty-nine SR and SR of SR were identified that reported workplace interventions including dietary components (see online supplementary material, Supplemental Table 1). Out of these SR, nineteen SR (published in twenty papers) were identified as distinctly reporting the effect of either dietary interventions or dietary intervention components on dietary behaviour and/or other outcomes. Two additional SR were identified in the updated search, so that the final analysis included twenty-one SR (published in twenty-two papers).

Fig. 1 Flowchart of the systematic review selection process (N, nutrition; SR, systematic review; WP, workplace)

Systematic review characteristics

Among the identified SR, three carried out a MA which all assessed different outcomes: weight( Reference Anderson, Quinn and Glanz 8 ), dietary behaviour( Reference Power, Kiezebrink and Allan 9 ) and theoretical framework( Reference Hutchinson and Wilson 10 ), and could therefore not be directly compared. To be included in the current SR of SR, the effect of the dietary part of the intervention had to be apparent. Only four of the SR evaluated solely dietary interventions( Reference Geaney, Kelly and Greiner 1 , Reference Jensen 2 , Reference Pomerleau, Lock and Knai 5 , Reference Steyn, Parker and Lambert 11 ), compared with other SR that evaluated general workplace wellness programmes including multiple behaviours such as physical activity, smoking and alcohol consumption. Interventions reviewed were conducted mainly in the USA or Western Europe. One SR explicitly reviewed interventions carried out in Europe( Reference Maes, Van Cauwenberghe and Van Lippevelde 12 ). All SR included interventions carried out in both male and female adults. None of the SR included focused on groups at high risk of disease and two SR focused on health-care professionals( Reference Power, Kiezebrink and Allan 9 , Reference Torquati, Pavey and Kolbe-Alexander 13 ). Therefore, no conclusions could be drawn with regard to nationality, work type, high-risk populations or other sociodemographic characteristics of the target population, as this was not examined in most SR. Three SR focused on weight-loss interventions( Reference Anderson, Quinn and Glanz 8 , Reference Power, Kiezebrink and Allan 9 , Reference Benedict and Arterburn 14 ) and four SR examined interventions focusing on environmental aspects( Reference Matson-Koffman, Brownstein and Greaney 15 – Reference Allan, Querstret and Banas 18 ). One SR looked at interventions to reduce major cancer risk factors( Reference Janer, Sala and Kogevinas 19 ) and Steyn et al. ( Reference Steyn, Parker and Lambert 11 ) focused on interventions published by the World Health Organization. The aims and objectives, as well as the focus of the interventions and outcomes of each SR, are reported in the online supplementary material, Supplemental Table 1. Outcomes that could most commonly be linked to the dietary intervention component were diet-related outcomes, such as fruit and vegetable (FV) intake (rather than health- or economic-related outcomes).

Study quality

Table 1 provides an overview of the quality of the SR according to AMSTAR criteria( Reference Shea, Grimshaw and Wells 7 ): five SR were of high quality (8–11 points)( Reference Geaney, Kelly and Greiner 1 , Reference Anderson, Quinn and Glanz 8 , Reference Power, Kiezebrink and Allan 9 , Reference Allan, Querstret and Banas 18 , Reference Osilla, Van Busum and Schnyer 20 ); fifteen were of medium quality (4–7 points)( Reference Jensen 2 – Reference Pomerleau, Lock and Knai 5 , Reference Hutchinson and Wilson 10 – Reference Engbers, Van Poppel, Chin and Paw 17 , Reference Janer, Sala and Kogevinas 19 , Reference Aneni, Roberson and Maziak 21 , Reference Wilson 22 ); and one was rated low quality (0–3 points)( Reference Riedel, Lynch and Baase 23 ).

Table 1 Quality of systematic reviews and meta-analysis under review rated according to the AMSTAR (‘assessment of multiple systematic reviews’) quality criteria

+, criteria met; o, criteria not met.

Diet-related outcomes

Dietary behaviour change outcomes most under review were FV consumption, overall diet, and fat and fibre intake (descending in order of frequency; Table 2). Strongest evidence was reported for improving fruit and/or vegetable intake. Four( Reference Geaney, Kelly and Greiner 1 , Reference Power, Kiezebrink and Allan 9 , Reference Allan, Querstret and Banas 18 , Reference Osilla, Van Busum and Schnyer 20 ) high-quality SR and all eight( Reference Jensen 2 , Reference Ni Mhurchu, Aston and Jebb 3 , Reference Pomerleau, Lock and Knai 5 , Reference Torquati, Pavey and Kolbe-Alexander 13 , Reference Kahn-Marshall and Gallant 16 , Reference Engbers, Van Poppel, Chin and Paw 17 , Reference Janer, Sala and Kogevinas 19 , Reference Aneni, Roberson and Maziak 21 ) medium-quality SR that reported FV intake as an outcome found that the number of studies reporting an increase in FV consumption outweighed the number of studies reporting no effect. Individual studies reviewed in the SR reported improvements in various ways, e.g. percentage of FV, grams of FV, portions or overall increase. The few SR that reported an increase in portions found an improvement of between 0·2 and 0·7 portions( Reference Geaney, Kelly and Greiner 1 , Reference Ni Mhurchu, Aston and Jebb 3 , Reference Pomerleau, Lock and Knai 5 , Reference Torquati, Pavey and Kolbe-Alexander 13 , Reference Matson-Koffman, Brownstein and Greaney 15 ). ‘Overall diet’ was reported in twelve SR( Reference Jensen 2 , Reference Glanz, Sorensen and Farmer 4 , Reference Power, Kiezebrink and Allan 9 , Reference Maes, Van Cauwenberghe and Van Lippevelde 12 , Reference Torquati, Pavey and Kolbe-Alexander 13 , Reference Matson-Koffman, Brownstein and Greaney 15 , Reference Kahn-Marshall and Gallant 16 , Reference Allan, Querstret and Banas 18 – Reference Wilson 22 , Reference Wilson, Holman and Hammock 24 ), with evidence being suggestive of a positive effect. Improvements in overall diet were defined as ‘significant improvements in any of the dietary factors’( Reference Janer, Sala and Kogevinas 19 ) or ‘increased consumption of healthier foods’ (e.g. FV, fibre, low-fat products)( Reference Power, Kiezebrink and Allan 9 , Reference Allan, Querstret and Banas 18 ) and two SR( Reference Power, Kiezebrink and Allan 9 , Reference Torquati, Pavey and Kolbe-Alexander 13 ) reported diet scores as well as other diet-related factors; however, no explanation was given on how individual studies calculated diet scores. Findings on change in total fat consumption were reported in eight( Reference Geaney, Kelly and Greiner 1 – Reference Ni Mhurchu, Aston and Jebb 3 , Reference Power, Kiezebrink and Allan 9 , Reference Hutchinson and Wilson 10 , Reference Engbers, Van Poppel, Chin and Paw 17 , Reference Janer, Sala and Kogevinas 19 , Reference Osilla, Van Busum and Schnyer 20 ), and on change in saturated fat consumption in two SR( Reference Power, Kiezebrink and Allan 9 , Reference Torquati, Pavey and Kolbe-Alexander 13 ), with mixed to positive results. Results on fat intake were generally reported as a reduction in fat consumption( Reference Power, Kiezebrink and Allan 9 , Reference Engbers, Van Poppel, Chin and Paw 17 ) and a few studies reported a percentage reduction in total fat, e.g. a change of between −9·1 and +1·3 % in energy from total fat( Reference Geaney, Kelly and Greiner 1 , Reference Ni Mhurchu, Aston and Jebb 3 , Reference Janer, Sala and Kogevinas 19 ). The evidence for change in fibre consumption was reported in four SR( Reference Jensen 2 , Reference Power, Kiezebrink and Allan 9 , Reference Engbers, Van Poppel, Chin and Paw 17 , Reference Janer, Sala and Kogevinas 19 ) and was conflicting. The four SR that looked at total energy intake all demonstrated positive effects( Reference Geaney, Kelly and Greiner 1 , Reference Power, Kiezebrink and Allan 9 , Reference Allan, Querstret and Banas 18 , Reference Osilla, Van Busum and Schnyer 20 ); however, the number of individual studies included in these SR was very limited.

Table 2 Summary of dietary, health and economic-related outcomes extracted from each systematic review/meta-analysis

WC, waist circumference; BP, blood pressure; ROI, return on investment; SR, systematic review; MA, meta-analysis; n/a, not assessed; D, diet; PA, physical activity; RCT, randomised controlled trial; WP, workplace; FV, fruit and vegetables; + , positive effect; F, fruit; V, vegetables; N, nutrition; POP, point-of-purchase labelling; ANR, outcomes were assessed but not reported; NC, data (as presented in SR) did not allow clear distinction between diet-related components; −, negative effect; HDL-C, HDL-cholesterol; TC, total cholesterol; WHR, waist-to-hip ratio.

The findings on diet-related behaviour change outcomes, such as diet knowledge, purchasing behaviour and attitudes towards healthy options, were also very limited. Three SR reported favourable findings on the effectiveness of dietary interventions to improve diet-related knowledge( Reference Geaney, Kelly and Greiner 1 , Reference Jensen 2 , Reference Steyn, Parker and Lambert 11 ). One of those SR( Reference Geaney, Kelly and Greiner 1 ) described one study that reported a score improvement of 1·34 (out of 10), whereas other SR reported a general knowledge improvement, without reporting scores( Reference Jensen 2 , Reference Steyn, Parker and Lambert 11 ). The association between dietary intervention and attitude towards diet was reported in only one medium-quality SR which concluded that results were not very strong; however, small positive results were reported( Reference Wilson 22 ). Self-efficacy was reported in one SR( Reference Geaney, Kelly and Greiner 1 ) and food purchasing patterns were reported in five SR( Reference Geaney, Kelly and Greiner 1 , Reference Glanz, Sorensen and Farmer 4 , Reference Matson-Koffman, Brownstein and Greaney 15 , Reference Kahn-Marshall and Gallant 16 , Reference Allan, Querstret and Banas 18 ). However, the number of studies that reported on these outcomes was relatively small so that no conclusion could be made and further evidence was needed. Overall, changes, although positive, were small and the potential impact as well as the long-term effectiveness on diet and health are unknown.

Health-related outcomes

In total, nineteen SR(Reference Geaney, Kelly and Greiner1–Reference Pomerleau, Lock and Knai5,Reference Anderson, Quinn and Glanz8–Reference Benedict and Arterburn14,Reference Kahn-Marshall and Gallant16–Reference Osilla, Van Busum and Schnyer20,Reference Wilson22–Reference Wilson, Holman and Hammock24) included health outcomes, five( Reference Geaney, Kelly and Greiner 1 , Reference Anderson, Quinn and Glanz 8 , Reference Power, Kiezebrink and Allan 9 , Reference Allan, Querstret and Banas 18 , Reference Osilla, Van Busum and Schnyer 20 ) of which were from high-quality SR. However, only nine SR( Reference Geaney, Kelly and Greiner 1 – Reference Glanz, Sorensen and Farmer 4 , Reference Power, Kiezebrink and Allan 9 , Reference Steyn, Parker and Lambert 11 , Reference Engbers, Van Poppel, Chin and Paw 17 , Reference Wilson 22 , Reference Riedel, Lynch and Baase 23 , Reference Wilson, Holman and Hammock 24 ) clearly drew conclusions with regards to the effectiveness of dietary interventions alone (Table 1), and results included mainly weight-related outcomes( Reference Geaney, Kelly and Greiner 1 – Reference Ni Mhurchu, Aston and Jebb 3 , Reference Power, Kiezebrink and Allan 9 , Reference Engbers, Van Poppel, Chin and Paw 17 ) and cholesterol( Reference Geaney, Kelly and Greiner 1 , Reference Jensen 2 , Reference Engbers, Van Poppel, Chin and Paw 17 , Reference Wilson, Holman and Hammock 24 ). Results from high-quality SR were not conclusive for dietary interventions alone, except for two SR( Reference Geaney, Kelly and Greiner 1 , Reference Power, Kiezebrink and Allan 9 ) that reported positive outcomes regarding reductions in weight and HDL-cholesterol and were based on a very limited number of studies. Overall results for weight-related outcomes ranged from a weight reduction of between −4·4 and −1·0 kg( Reference Jensen 2 , Reference Ni Mhurchu, Aston and Jebb 3 , Reference Power, Kiezebrink and Allan 9 ), which was in line with a reduction in energy intake, to a statistically significant BMI (kg/m2) increase( Reference Geaney, Kelly and Greiner 1 , Reference Ni Mhurchu, Aston and Jebb 3 , Reference Engbers, Van Poppel, Chin and Paw 17 ). Cholesterol reductions were generalised in most studies as a ‘significant decrease in cholesterol’ and Geaney et al. ( Reference Geaney, Kelly and Greiner 1 ) reported an increase in HDL-cholesterol by 0·06 mmol/l. One SR reported overall positive long-term health improvements as a result of dietary interventions( Reference Riedel, Lynch and Baase 23 ). Blood pressure was another commonly reported measure; however, it was unclear whether change in blood pressure was due to a change in dietary behaviour. That applies also to other health-related outcomes, such as blood glucose levels and overall morbidity and mortality, which were reported less often.

Economic-related outcomes

In eight SR (two of high quality( Reference Anderson, Quinn and Glanz 8 , Reference Osilla, Van Busum and Schnyer 20 ), three of medium quality( Reference Jensen 2 , Reference Steyn, Parker and Lambert 11 , Reference Benedict and Arterburn 14 ) and one of low quality( Reference Riedel, Lynch and Baase 23 )), work-related outcomes, i.e. productivity, return on investment, health-care costs and sickness/absenteeism, were assessed (Table 1). Three of these SR did not find information on economic outcomes in the individual intervention studies under review( Reference Geaney, Kelly and Greiner 1 , Reference Ni Mhurchu, Aston and Jebb 3 , Reference Benedict and Arterburn 14 ). Furthermore, three SR reported findings but could not draw conclusions with regard to dietary interventions alone( Reference Anderson, Quinn and Glanz 8 , Reference Osilla, Van Busum and Schnyer 20 , Reference Riedel, Lynch and Baase 23 ). Only two medium-quality SR reported a positive change in work-related outcomes as a result of a dietary intervention, i.e. that interventions were cost-effective( Reference Steyn, Parker and Lambert 11 ) and reduced absenteeism as well as costs due to loss of productivity( Reference Jensen 2 ). No specific values were provided, except for one study included in the SR by Jensen that reported a reduction in absenteeism by 20 % which was the equivalent of three days( Reference Jensen 2 ). Kahn-Marshall and Gallant( Reference Kahn-Marshall and Gallant 16 ) also noted that environmental and policy-based interventions were low-cost to implement.

Evaluation outcomes

Evaluation outcomes such as attrition( Reference Benedict and Arterburn 14 ), staff participation and feasibility of the interventions were often not reported. No adverse intervention outcomes or financial losses were found. A criticism of individual studies included in the SR was that any problems in study implementation and study fidelity were frequently not reported( Reference Maes, Van Cauwenberghe and Van Lippevelde 12 , Reference Allan, Querstret and Banas 18 ). Some SR did report information on the intervention workplaces but did not make comments on intervention effectiveness with regard to the kind of workplace or workplace size, except for some SR which highlighted that most interventions are carried out in medium- and large-sized businesses and interventions may not be suitable for smaller businesses( Reference Jensen 2 , Reference Anderson, Quinn and Glanz 8 , Reference Kahn-Marshall and Gallant 16 , Reference Janer, Sala and Kogevinas 19 , Reference Osilla, Van Busum and Schnyer 20 ). Anderson et al. noted that one potential benefit of workplace well-being projects would be to improve the relationship between staff and management( Reference Anderson, Quinn and Glanz 8 ). Interventions were criticised, however, for not including qualitative evaluation findings that would help explore that aspect( Reference Ni Mhurchu, Aston and Jebb 3 ).

Findings for most effective intervention

Due to the high heterogeneity in the design of the interventions under review and in SR, there was a lack of consistency in findings of what interventions were most effective. Therefore, a summary of suggestions that were pointed out by at least some of the SR is presented in Table 3. Only findings from high- and medium-quality studies have been summarised.

Table 3 Limitations from previous research and recommendations for the future (high- and medium-quality studies only)

Discussion

Overall findings

The current SR of SR synthesises best available evidence from SR and MA evaluating dietary workplace interventions. Individual workplace dietary interventions assessed a range of outcomes and the heterogeneity of reported findings made it challenging to summarise results. Overall, positive effects for increasing FV consumption and overall diet, increasing diet knowledge, aiding weight loss and reducing total cholesterol were reported. Improvements in health- and diet-related outcomes were often small but may potentially be clinically significant, i.e. a reduction in total fat intake has been linked to a reduction in body weight and improvement in LDL-cholesterol and total cholesterol, as well as the ratio between HDL- and LDL-cholesterol( Reference Hooper, Summerbell and Thompson 25 ). Furthermore, an improvement in FV intake by up to 0·7 portions is an important improvement, considering that FV intake has stagnated over recent years( 26 ). None of the SR distinguished between dietary behaviour at home in comparison to dietary behaviour at work. Change in diet throughout the week, however, is important, as it might indicate whether or not employees are likely to continue with the positive changes they have made at work( Reference Geaney, Kelly and Greiner 1 , Reference Ni Mhurchu, Aston and Jebb 3 ). Few studies examined the effect of dietary interventions alone on work-related outcomes. Overall, findings suggest that outcomes from dietary interventions may help to reduce employer’s expenses. Cancelliere et al. found that people who had a poor diet and were overweight were more likely to suffer from absenteeism( Reference Cancelliere, Cassidy and Ammendolia 27 ), which suggests that dietary interventions may result in cost savings due to preventing presenteeism as well as absenteeism. Further supportive evidence on cost savings is available for workplace well-being projects in general, rather than specifically dietary interventions, that were not included in the current SR of SR( Reference Baicker, Cutler and Song 28 , Reference Baxter, Sanderson and Venn 29 ).

Type of intervention

The majority of SR looked at interventions targeting multiple health behaviours. The evidence on whether dietary interventions alone or in combination with other health behaviours are more effective in improving health is mixed. A number of SR suggested that intensive interventions (i.e. interventions with numerous intervention components) are most effective( Reference Anderson, Quinn and Glanz 8 , Reference Engbers, Van Poppel, Chin and Paw 17 ) and that environmental changes (e.g. improving food choices in canteens and vending machines and labelling healthy options) should be included( Reference Geaney, Kelly and Greiner 1 , Reference Steyn, Parker and Lambert 11 , Reference Aneni, Roberson and Maziak 21 ), although not all authors were able to draw that conclusion( Reference Ni Mhurchu, Aston and Jebb 3 , Reference Allan, Querstret and Banas 18 ). One large multicomponent randomised controlled trial (twenty-four worksites) that included environmental aspects was conducted by Sorensen et al. ( Reference Sorensen, Stoddard and Peterson 30 ) in the USA. The intervention comprised education, food tastings, family training, increased availability of FV and food labelling. The study reported that the most intensive intervention arm (including the family component) was most successful and reported a significant increase in FV consumption. The Seattle 5 a Day Worksite Program by Beresford et al. ( Reference Beresford, Thompson and Feng 31 ) (twenty-eight worksites) also delivered multiple intervention components such as changes to the work environment (catering policies, healthier options in vending machines, etc.) and individual education components (e.g. cooking classes and posters), and reported an increase in FV consumption in the intervention sites compared with control sites.

This is in agreement with the Overcoming Obesity report by the McKinsey Global Institute, which outlines that healthy choices should be made easily accessible and less healthy choices should be made less easily accessible, to nudge healthier diet behaviour( Reference Dobbs, Sawers and Thompson 32 ). In a recent commentary, public health experts highlighted the need to reduce unhealthy nudges that can be detrimental to efforts made in public health and to increase positive nudges( Reference Marteau, Ogilvie and Roland 33 ). One limitation of interventions that have reported changes of the environment is that these are often carried out in workplace canteens. Therefore, the evidence for workplaces without canteen facilities on-site is limited and, in future, it should also be explored what works in smaller workplaces that often do not provide canteen facilities.

Systematic review quality

The SR were generally of medium quality, with few SR of high quality. It has to be taken into account that AMSTAR criteria were published in 2007, after some of the earlier SR were carried out, and therefore less guidance was available for researchers at the time. Furthermore, some of the criteria were not applicable and therefore the score may not accurately present the quality of each SR, namely: (i) ‘combining findings’, which indicates pooling of results and was not applicable for most SR due to the heterogeneity and may be more applicable for MA; (ii) ‘conflict of interest’ has only recently been introduced; (iii) ‘publication bias’, which is generally assessed through funnel plots, was also not applicable for most studies (the score for publication bias was given for SR that did not carry out a MA when publication bias was discussed); and (iv) depth of information on ‘study characteristics’ varied widely between studies. The quality scoring criteria used also varied in most SR, and few SR performed a formal quality assessment. A point was given for this criterion for a less formal consideration of study designs. Under ‘quality in conclusions’, only SR that clearly discussed their findings together with the quality of SR were scored a point.

Strengths and limitations

The current SR has extracted the results from the best knowledge sources available on dietary interventions or dietary intervention components, so that researchers, policy makers and employers have a reliable source of information when implementing dietary interventions in the workplace. However, by including SR only, important findings from other reviews may have been overlooked. Although we aimed to review only dietary interventions in the workplace, because most SR targeted multiple health behaviours, some of the conclusions made with regards to intervention delivery may overlap with recommendations for workplace interventions in general.

Publication bias (i.e. only successful interventions are published) and selection bias (i.e. participants who volunteered to take part in studies are more likely to want to change) in individual studies are a possible explanation for the positive findings of SR( Reference Van Dongen, Proper and Van Wier 34 ). However, the improvement in outcomes reported in each SR as a result of dietary interventions in the workplace is relatively small and therefore it seems unlikely that results were skewed by this bias. The limitations of the individual interventions are also limiting the current SR of SR in its conclusions, such as self-reporting of diet outcomes, imprecise reporting of work-related outcomes, limited follow-up periods, missing information on intervention reach and lack of thorough evaluation (i.e. lack of process evaluation and use of qualitative as well as quantitative data collection). Osilla et al., for example, highlight that incentives are commonly used as part of workplace well-being programmes( Reference Osilla, Van Busum and Schnyer 20 ); however, there is little information on their effectiveness.

Another limitation of the current SR is that scores for the quality of SR were given only when the SR clearly stated the required criterion and therefore some of the SR may have been judged inappropriately. It is hoped this will encourage researchers in future to clearly describe how quality criteria have been met to ensure researchers produce a good evidence base. The lack of rigorous study design, i.e. non-randomised and non-controlled trials, was commented on by a number of authors( Reference Anderson, Quinn and Glanz 8 , Reference Power, Kiezebrink and Allan 9 , Reference Engbers, Van Poppel, Chin and Paw 17 ); however, others argue that randomised controlled trials are not the most appropriate designs for public health interventions and that researchers should rather aim to increase efficacy, reach and uptake of interventions( Reference Maes, Van Cauwenberghe and Van Lippevelde 12 ). This argument was further explored by O’Donnell who argues that representative sampling, measures that appropriately assess the outcomes, correct use of statistical analysis and consideration of the elements of the programme are more important in a robust study methodology than a randomised controlled trial design( Reference O’Donnell 35 ). Further, he argues that it is impossible to control the different factors of a comprehensive workplace programme and mentions key factors that are more important, including management support and a company-tailored programme, which agrees with SR discussed here( Reference Ni Mhurchu, Aston and Jebb 3 , Reference Steyn, Parker and Lambert 11 , Reference Janer, Sala and Kogevinas 19 ). Investors and business owners want to get the best return for their time and resource investment, which is another reason why randomised controlled trials may not be the most suitable design for these interventions and before-and-after designs are commonly implemented( Reference Pelletier 36 ). One way to evaluate non-controlled interventions would be to introduce intervention components in a staged manner( Reference Power, Kiezebrink and Allan 9 ).

Comparison with the literature

A limited number of SR of SR reported findings on behaviour change in the workplace, including a change in eating habits. Greaves et al., for example, found that engaging in social support and targeting both diet and PA behaviour as well as building interventions on behaviour change techniques increased intervention effectiveness in type 2 diabetes patients( Reference Greaves, Sheppard and Abraham 37 ). Findings from another SR of SR suggested workplace settings are most effective in changing diet, as well as other health behaviours, compared with community-based settings or individual interventions( Reference Jepson, Harris and Platt 38 ) and that environmental changes to the canteen environment, such as increased availability of healthier food and drink options, together with the labelling of healthier options, were effective in encouraging people to eat a healthier diet( Reference Mozaffarian, Afshin and Benowitz 39 ). This is in agreement with the findings of the current SR of SR, as the majority of interventions recommended the inclusion of environmental changes when designing dietary interventions for workplaces. The most recent SR of SR in this area of research included SR on multiple health behaviours and only three SR reported dietary interventions( Reference Schröer, Haupt and Pieper 40 ). It also lacked quality assessment of the SR and was therefore limited in its conclusions. By thoroughly assessing solely the dietary component of each SR under review, the outcomes of the present research have added valuable insight into the effectiveness of dietary studies alone on diet-, health- and economic-related outcomes.

Application of findings

The findings need to be considered with caution, as most SR have looked at well-being interventions that addressed multiple behaviours. Improvement in diet could be clearly linked to the dietary components; however, conclusions drawn with regards to health- and economic-related outcomes are limited. The reviewed interventions were mainly carried out in the USA or Western Europe and findings of the current SR may not be applicable elsewhere. However, two SR, excluded here, discussed initiatives in Latin America( Reference Mehta, Dimsdale and Nagle 41 ) and New Zealand( Reference Novak, Bullen and Howden-Chapman 42 ). No recommendations can be made with regard to the type of work, age or gender, as these were not reported in the included SR, and the two SR that looked at interventions in health-care professionals were not able to draw conclusions( Reference Power, Kiezebrink and Allan 9 , Reference Torquati, Pavey and Kolbe-Alexander 13 ). Studies not included in the current SR also looked at blue-collar workers( Reference Groeneveld, Proper and Van Der Beek 43 ), health-care professionals( Reference Chan and Perry 44 ), overweight and obese populations( Reference Pearson 45 ), and groups at risk of CVD( Reference Novak, Bullen and Howden-Chapman 42 , Reference Groeneveld, Proper and Van Der Beek 43 ).

Future research

While there is a small number of studies looking at different study populations, there is a need for further research to identify the effectiveness of dietary workplace interventions in different populations. Interventions and messages should be tailored to the study population and adapted to the requirements of each workplace to increase effectiveness. For intervention success, it is essential to make use of the unique opportunity that the workplace setting provides, i.e. nudge the environment, involve employees in intervention planning and delivery, and encourage effective leadership and management support. Intervention studies should also be set up over a longer period of time to assess long-term improvements. To improve comparability between study outcomes, gold standard measurements need to be developed to measure economic-related outcomes and a mixed-methods approach should be applied to assess the ‘how’ and ‘why’ as well as the ‘what’ has changed( Reference Geaney, Kelly and Greiner 1 ).

As the ultimate goal of research is to enhance practice and learn from previous findings, it is important to carefully evaluate each intervention and report in detail: (i) all intervention components, planned and delivered, so that future research may be able to replicate or tweak what has been done previously; (ii) participant as well as workplace characteristics (including management buy-in); and (iii) all relevant outcomes, including participant retention rate and fidelity of intervention delivery. MRC (Medical Research Council) guidelines should be followed to design and evaluate complex interventions( Reference Craig, Dieppe and Macintyre 46 ) and TREND (Transparent Reporting of Evaluations with Nonrandomized Designs) guidelines used for the accurate reporting of non-randomised trials( Reference Jarlais, Lyles and Crepaz 47 ).

Conclusion

Dietary workplace interventions seem to have small positive effects, in the short term, on increasing FV intake, reducing fat intake, aiding weight loss and reducing cholesterol. There is no ‘one design fits all’; thus intervention designers should shift their focus from finding the ‘perfect’ design and apply some crucial criteria that have been repeatedly mentioned to improve the chances of intervention success, including tailoring the intervention to the workforce, aiming for high participation and low dropout rates, utilising the unique social and environmental assets of the workplace, ensuring management support and employee involvement, incorporating multiple components, considering eating habits at work and outside the workplace, carrying out mixed-methods process evaluation, and measuring health- and economic-related outcomes. More transparency in reporting of what did and did not work and what was well accepted by staff is encouraged, so that policy makers, employers and other researchers can learn from future efforts. Workplace dietary interventions seem to have the potential to improve some aspects of dietary behaviour and health outcomes, which is likely to save companies costs in the long term.

Acknowledgements

Financial support: This work was supported by the John Wilson Memorial Trust. The John Wilson Memorial Trust had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. Conflict of interest: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest. Authorship: D.S. and J.V.W. formulated the research question. D.S. carried out the search and conducted the title screen. D.S. and J.V.W. conducted the abstract and full-text screens independently. D.S. extracted all information into predefined templates, which were checked by J.V.W. Both authors conducted the quality review independently and differences were resolved through discussion. D.S. wrote the manuscript, which was guided by J.V.W. Ethics of human subject participation: Not applicable.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980018003750