The unusually dry summer of 2018 brought exceptional conditions for aerial archaeology across Britain and Ireland. Arguably, some of the most striking discoveries of this drought came from Ireland and, in particular, from the Brú na Bóinne World Heritage site, revealing a series of cropmark enclosures including some of unusual design (Condit & Keegan Reference Condit and Keegan2018). In parallel to these remarkable aerial discoveries, many other previously unidentified archaeological features have been revealed by an ongoing programme of large-scale geomagnetic survey, covering c. 350 ha of the World Heritage Site core area and buffer zones since 2014. These discoveries provided the initial impetus for this review, the main objective of which is to provide an up-to-date survey of the late Neolithic monumentality of Brú na Bóinne and to place some of these recent discoveries in a regional context. It must be stressed at the outset that any synthesis of these sites is severely hampered by the lack of excavation of Irish henge monuments in recent decades (cf. Smyth Reference Smyth2009, 91). Much of the information presented here can therefore only be based upon analogies with excavated sites in Ireland and elsewhere and interpretations are likely to be subject to change with any future excavation and dating of archaeological features.

THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL ENSEMBLE OF THE BEND IN THE BOYNE (BRÚ NA BÓINNE)

Brú na Bóinne is one of only two UNESCO World Heritage Sites in the Republic of Ireland and one of the most significant prehistoric archaeological landscapes in Europe. The ‘Bend in the Boyne’ occupies a broad, rock-cut meander in the river, bounded to the north by a second, smaller river, the Mattock (Lewis et al. Reference Lewis, Gallagher, Davis, Turner, Foster, Brown, Breda, Mulrooney, Guinan, Brady and Meehan2017). The area is best known for its Neolithic passage tombs, especially the large developed tombs of Knowth, Dowth, and Newgrange, which were constructed towards the end of the 4th millennium bc (see dates summarised in Smyth Reference Smyth2009; Eogan & Cleary Reference Eogan and Cleary2017), and for the remarkable corpus of megalithic art within the necropolis (c. 400 decorated stones at Knowth alone; O’Sullivan Reference O’Sullivan2006).

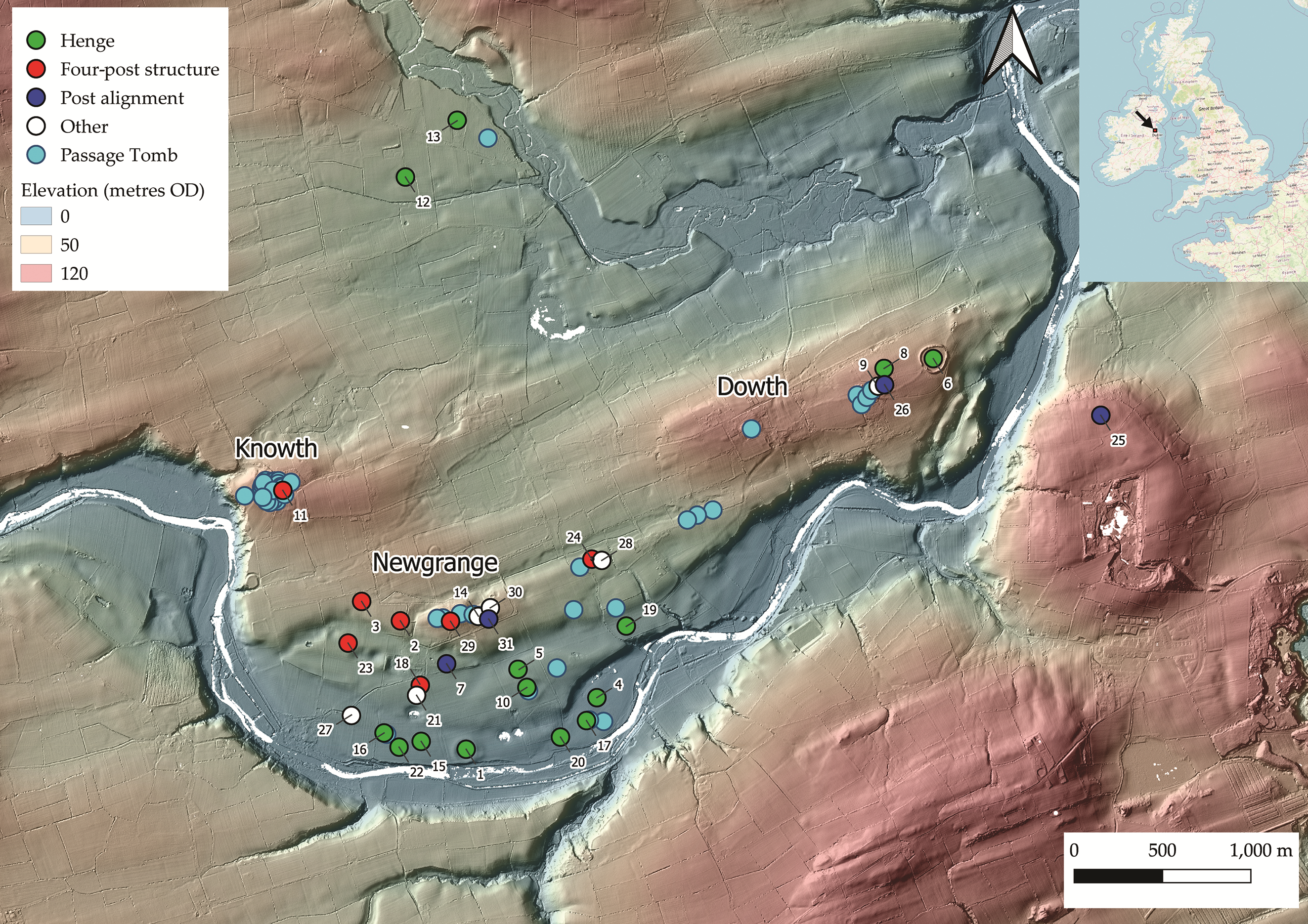

In addition to the middle Neolithic tombs, for which it is justifiably famous (Herity Reference Herity1975; Eogan Reference Eogan1986; Eogan & Doyle Reference Eogan and Doyle2010), Brú na Bóinne preserves a remarkable collection of probable late Neolithic monuments that are especially concentrated in the area between Newgrange and the River Boyne. These comprise an increasingly diverse group of earthen and timber monuments, most likely dating to the early–middle 3rd millennium bc. They include ‘embanked enclosures’ (see Stout Reference Stout1991) or henge monuments (see below), circular/sub-circular enclosures incorporating a central four-post setting (‘square-in-circle’ monuments or ‘four-post structures’ – eg, Bradley Reference Bradley2007, 119; Noble et al. Reference Noble, Greig, Millican, Anderson, Clarke, Johnson, McLaren and Sheridan2012; Carlin & Cooney Reference Carlin, Cooney, Stanley, Swan and O’Sullivan2017), and timber structures, including palisades and post alignments. This monumental complex has seen relatively little ground-based research and has largely been discovered in recent years through aerial photography, satellite imagery, analysis of LiDAR data, and large-scale geomagnetic surveys (Davis et al. Reference Davis, Brady, Megarry, Barton, Cowley and Opitz2013; Megarry & Davis Reference Megarry, Davis, Comer and Harrower2013 Condit & Keegan Reference Condit and Keegan2018; Davis Reference Davis2018; Leigh et al. Reference Leigh, Stout and Stout2018; Rassmann et al. Reference Rassmann, Davis and Gibson2019; see Fig. 1 & Table 1). Along with chance discoveries of late Neolithic material during excavations in the vicinity of Knowth and Newgrange these sites, many of which have little or no surface expression, are crucial to our understanding of Brú na Bóinne in the period following passage tomb construction.

Fig. 1. LiDAR-based 32-direction hillshade showing potential late Neolithic sites. Passage tomb and probable passage tomb locations also marked. Elevation data over 32-direction hillshade. For key see Table 1 (LiDAR data courtesy of Meath County Council)

TABLE 1: SITES MARKED IN FIG. 1

Means of discovery: AP = aerial photography; G = geophysics; E = excavation; ALS = airborne laser scanning (LiDAR). Other sites were recorded historically.

Site type: H = henge; 4P = four-post structure; PA = post alignment; OT = other.

1 Site name after Condit & Keegan (Reference Condit and Keegan2018).

2 Site name after Davis et al. (Reference Davis, Brady, Megarry, Barton, Cowley and Opitz2013).

A note on site names in Brú na Bóinne

Historically, sites within Brú na Bóinne were assigned single letter identifiers, first by Coffey (Reference Coffey1912) with subsequent revision by Claire O’Kelly (Reference O’Kelly1978); while initially useful, this led to an inevitable shortage once the end of the alphabet was reached with Tomb Z (O’Kelly et al. Reference O’Kelly1978). This has in turn led to a more ad hoc naming of sites in recent years, such as the sites regrettably identified by one of the authors as Sites LP1 and LP2 (LP = Low Profile; Davis et al. Reference Davis, Brady, Megarry, Barton, Cowley and Opitz2013) and the more recent descriptive names assigned by Condit and Keegan (Reference Condit and Keegan2018) such as ‘The Great Palisade’, ‘The Geometric Henge’ and the ‘Great Rectangular Palisade Enclosure’. Clearly the naming of these sites is long overdue for revision. In the current paper O’Kelly’s (Reference O’Kelly1978) identifiers are used where possible; however, ‘new’ sites are lacking these and so they are primarily referred to using the unique Irish Sites and Monuments Record (SMR) number.Footnote 1 Most of the potential archaeological sites identified by the ongoing campaign of geomagnetic survey have not yet been included in the SMR database and have each been assigned a unique identifier within the survey GIS, comprising a two or three-letter townland abbreviation and a site number. These are summarised in Table 1 and Figure 1, which also identifies the means by which more recently discovered sites have been identified. Additionally, within Brú na Boinne there remain issues of classification regarding some site types. Some sites that are almost certainly passage tombs and have been discussed as such within the literature (eg, the Ballinacrad tombs; Cooney Reference Cooney2000, 154) are recorded within the SMR and RMP as mound barrows and/or mounds. Similarly, the classifications ‘henge’ and ‘embanked enclosure’ are used interchangeably and seemingly arbitrarily. For the purposes of this paper, henges and embanked enclosures are regarded as indistinguishable. Passage tombs, mound barrows, and mounds within Brú na Bóinne are more problematic and have tended to be treated as ‘known unknowns’ – sites that are widely known and accepted as passage tombs (eg, Herity Reference Herity1975) but are not classified as such within the Irish RMP or SMR.

EXCAVATION AND CHRONOLOGY

As already stated, there has been little excavation of henge monuments or timber circles within Brú na Bóinne in recent decades and no earthen henge monument has been excavated here since the partial excavations at Monknewtown (Sweetman Reference Sweetman1971; Reference Sweetman1976). Both O’Kelly et al. (Reference O’Kelly, Cleary, Lehane and O’Kelly1983) and Sweetman et al. (Reference Sweetman, O’Sullivan, Gunn, Monk, Donnabháin and Scannell1985) excavated elements of the Newgrange Pit Circle, with further excavations undertaken at the possible Western Circle (Sweetman et al. Reference Sweetman, McCormick and Mitchell1987) and the Knowth four-post structure (Eogan & Roche Reference Eogan and Roche1997; Reference Eogan, Roche, Cleal and MacSween1999). In this context, the test excavation of part of the ‘Great Rectangular Palisade’ in 2018 (Leigh et al. Reference Leigh, Stout and Stout2018; Reference Leigh, Stout and Stout2019) represents the most significant recent excavation within the Brú na Bóinne late Neolithic complex. While the dates from the Knowth four-post structure, possible Western Circle, and Newgrange Pit Circle cluster in the early–middle 3rd millennium bc, those from the Monknewtown Henge remain highly problematic, ranging from the middle Neolithic through to the early medieval period. These dates are summarised in Smyth (Reference Smyth2009, appendix iv).

THE ‘EMBANKED ENCLOSURES’ OR HENGES OF BRÚ NA BÓINNE

The class of monuments known in Ireland as ‘embanked enclosures’ are generally considered to be analogous to British henge monuments (Stout Reference Stout1991; Condit & Simpson Reference Condit and Simpson1998; O’Sullivan et al. Reference O’Sullivan, Davis and Stout2012). In form these mostly comprise large (140–200 m), saucer-shaped earthen enclosures, most of which are greatly denuded with surviving banks significantly less than 1 m in height. They are predominantly located on the lower terraces of the Boyne and incorporate a gentle to moderate slope, often facing towards water (cf. Richards Reference Richards1996).

In her comprehensive (for the time) review of the Boyne embanked enclosures, Stout (Reference Stout1991) suggested that these monuments did not have internal ditches as in classic British henge monuments but were, instead, formed by scarping out an area internal to the line of the bank in order to create material for bank construction. This ditchless form has become widely accepted as normal for Ireland (eg, Harding Reference Harding2003, 19) and has led to comparison with British sites lacking a ditch such as Mayburgh, Cumbria (Topping Reference Topping1992). While this does appear to be the case in some Irish sites (eg, Ballynahatty, Co. Down and Fourknocks, Co. Meath), geophysical survey (eg, Davis Reference Davis2013; Davis et al. Reference Davis, Brady, Megarry, Barton, Cowley and Opitz2013, and unpublished data), aerial photography (Condit & Keegan Reference Condit and Keegan2018), and limited excavation (eg, Danaher Reference Danaher2005; Reference Danaher and Danaher2007; Ó Donnchadha & Grogan Reference Ó Donnchadha and Grogan2010) have, in recent years, shown the situation to be much more complex with a number of sites now shown to have at least internal and, in some cases, external ditches.

Most Irish sites appear to possess only a single opening; however, both Dowth Henge and Newgrange Site P have indications of dual opposing entrances. The lack of any obvious opening in many of these sites is problematic but may indicate that the original entrance was relatively unelaborated, perhaps just a narrow break in the bank as appears to be the case in the west of Newgrange Site P. Similarly, at Tonafortes, Co. Sligo, Danaher (2007, 46) describes the entrance as comprising ‘an 8.2m-wide undug causeway … [with] no other associated features’. It is also possible that the lack of obvious entrance features is indicative of deliberate ‘blocking’ of entrances as sites fell from use (cf. Brophy & Noble Reference Brophy and Noble2012). The status of these monuments in Ireland is far from clear, with a wide-ranging review by Condit and Simpson (Reference Condit and Simpson1998) identifying a very broad spectrum of potential ‘hengiform’ sites; to some extent this emphasises the point eloquently made by Alex Gibson (2012): that archaeologists can no longer clearly define what a henge actually is.

ARCHAEOLOGICAL PROSPECTION IN BRÚ NA BÓINNE: LIDAR AND AERIAL SURVEY

Prior to 2010 there were four recorded embanked enclosures/henge monuments in the wider Brú na Bóinne landscape: the Monknewtown Henge, partially excavated by Sweetman (Reference Sweetman1971; Reference Sweetman1976) and subsequently largely destroyed; Sites A and P between Newgrange and the Boyne; and Dowth Henge (more rarely referred to as Site Q) to the east. The anomalous ‘ritual pond’ at Monknewtown is also a developed monument of this class, comprising a high enclosing bank surrounding a sunken, water-retaining central area. A radiocarbon date of 2847–2469 cal bc was obtained from a core through the waterlogged external ditch fill (Beta-288747; 4050±40 bp: Davis et al. Reference Davis, Megarry, Brady, Lewis, Cummins, Guinan, Turner, Gallagher, Brown and Meehan2010; recalibrated using IntCal20: Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Austin, Bard, Bayliss, Blackwell, Bronk Ramsey, Butzin, Cheng, Edwards, Friedrich, Grootes, Guilderson, Hajdas, Heaton, Hogg, Hughen, Kromer, Manning, Muscheler, Palmer, Pearson, Plicht, Reimer, Richards, Scott, Southon, Turney, Wacker, Adolphi, Büntgen, Capano, Fahrni, Fogtmann-Schulz, Friedrich, Köhler, Kudsk, Miyake, Olsen, Reinig, Sakamoto, Sookdeo and Talamo2020). Sites A and P are similar in gross morphology, both being shallow and dish-shaped with no topographic evidence of either an inner or outer ditch or of internal scarping. They are flattened to their western side, possess broad, low banks, and each also includes an unusual annex to the eastern side, creating an additional defined space between the main enclosure and an apparent entrance (Stout Reference Stout1991; O’Sullivan et al. Reference O’Sullivan, Davis and Stout2012; Davis et al. Reference Davis, Brady, Megarry, Barton, Cowley and Opitz2013). Site A encloses a substantial mound, most likely a passage tomb, but interpretation of the site is hampered by significant damage that occurred in the 1960s (O’Kelly et al. Reference O’Kelly, Lynch, O’Kelly, Twohig, Erskine, McCormick and Roche1978, 50). While Dowth Henge is also flattened to one side (the south-west) it is substantively different from the other recorded Boyne sites, both in terms of its landscape position and gross morphology: it is situated in an elevated position above the Boyne and has substantial, well-preserved banks, dual opposing entrances and clear evidence of internal scarping. Arguably, however, the eccentric ovoid form seen at Dowth Henge is equivalent to the primary phase of Sites A and P (and of site ME026-033 – see below), representing the outline of the enclosure plus annex (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Henges/embanked enclosures in Brú na Bóinne: top left: ME026-033 (‘Dronehenge’); transcribed from aerial photography; top right: Site P; bottom left: Site A; bottom right: Dowth Henge; 32-direction LiDAR hillshade overlain with outlines of henge Sites A, P and ME026-033 plus annexes (aerial photography © BlueSky 2018; LiDAR data courtesy of Meath County Council)

LiDAR analysis in 2010 identified a further four possible henge monuments (Table 1; Fig 1: Sites 8, 9, 13 & 19) between Newgrange and the River Boyne (O’Sullivan et al. Reference O’Sullivan, Davis and Stout2012; Davis et al. Reference Davis, Brady, Megarry, Barton, Cowley and Opitz2013), some of which have subsequently been confirmed by aerial photography (Condit & Keegan Reference Condit and Keegan2018). The same programme of research also identified a fifth site of this type at Carranstown, Co. Meath, a further 6 km south-east of Newgrange, midway between the cluster of sites in Brú na Bóinne and a second group of at least three henge monuments associated with the passage tomb cemetery at Fourknocks, Co. Meath (Stout Reference Stout1991; O’Sullivan et al. Reference O’Sullivan, Davis and Stout2012).

Aerial photography has contributed significantly to our understanding of the construction of these monuments, especially in the context of Collins’s (Reference Collins1957) excavations at the Giant’s Ring, Ballynahatty, Co. Down. Collins proposed a three-phase bank construction: an outer gravel ‘guide’ enclosure (most likely an early construction phase), insubstantial but defining the periphery of the bank; the main body of the bank made from earth and stone; and a boulder revetment placed on the inner shoulder of the monument (Fig. 3). Elements of this phased construction are apparent in aerial images of Site P taken over several decades. While the main body of the bank is visible as a substantial parchmark, an outer parchmark enclosure can also be seen in dry years (eg, 2018; Fig. 3). At Site P, the eastern annex, rather than being continuous with the main bank, is instead an extension of the outer enclosure. The irregular nature of the parchmark, especially in the annex, may suggest a segmented construction technique, also argued by Condit and Keegan (Reference Condit and Keegan2018, 85–9) for Site A. Aerial imagery also suggests the presence of an opposing, unelaborated narrow western entrance at Site P, present as a break in the parchmark of the main bank (Stout Reference Stout1991, 247), and an internal ditch, neither of which are evident in the LiDAR survey.

Fig. 3. Top: Newgrange Site P, July 2018 (aerial photograph courtesy of Anthony Murphy); bottom: Section through bank at the Giant’s Ring, Ballynahatty (after Collins Reference Collins1957).

Aerial photography from 2018 (Condit & Keegan Reference Condit and Keegan2018; Ken Williams pers. comm.) has led to substantially more detail being visible for ME019-094 (Site LP2: Davis et al. Reference Davis, Brady, Megarry, Barton, Cowley and Opitz2013) in addition to the identification of at least one, and up to four, previously unidentified monuments probably in this class.

The most striking of these new discoveries has become colloquially known as ‘Dronehenge’ (Murphy Reference Murphy2019) owing to it being first identified in drone imagery by local photographers Anthony Murphy and Ken Williams. The site has subsequently been alternatively called the ‘Geometric Henge’ by Condit and Keegan (Reference Condit and Keegan2018) but is referred to here by its SMR number, ME026-033 (Figs 2, 4 & 5). It possesses remarkable similarities to Site P (Fig. 5) and to ME019-094, the two sites located directly to its east and west (Fig. 4). The most unexpected new feature visible at both ME019-094 and ME026-033 is the segmented form of the main ditch circuits. In the case of ME019-094 (see further discussion below) the ditch comprises a single segmented circuit with suggestions of an external parchmark representing the low bank previously observed with LiDAR and most likely analogous to Collins’ gravel enclosure; however, in ME026-033 these ditch sections are doubled, resulting in a unique segmented double ditch form. As in Site P and Site A, an eastern annex is also evident at ME026-033, in this case as a separate section of segmented ditch using the same architectural motif as the main enclosure. The entrance into the annex is flanked by additional ditch sections, so that here there are three rather than two segments, with substantial pits or post-holes positioned either side, perhaps forming a façade.

Fig. 4. Brú na Bóinne henges: left: ME026-094 (Site LP2; Davis et al. Reference Davis, Brady, Megarry, Barton, Cowley and Opitz2013; ‘The Univallate Henge’; Condit & Keegan Reference Condit and Keegan2018); centre: ME026-033 (‘Dronehenge’); right: Site P. River Boyne to south of image (LiDAR 32-direction hillshade courtesy of Meath County Council).

Fig. 5. Left: ME026-033, otherwise known as ‘The Geometric Henge’ (Condit & Keegan Reference Condit and Keegan2018) or ‘Dronehenge’ (Murphy Reference Murphy2019) (transcribed from aerial imagery © BlueSky 2018 & from orthophotography provided by Ken Williams); right: Transcribed outline of ME026-033 overlain on Site P, rotation 10.8o anticlockwise. Scale identical

Directly opposite the annex, in the position that in Site P is occupied by the narrow second entrance, is a rectangular structure. The inner (henge) side of this comprises a series of six substantial pits or post-holes which form one side of a rectangular ditched structure with a narrow, extended entrance feature on the western side. Two large internal post-holes constitute possible roof supports and suggest this represents a roofed building. The series of six pits/post-holes corresponds with a low mound previously identified through LiDAR survey (Davis et al. 2010) and is evident as a parchmark in the Reference Davis2018 data. This suggests a possible low bank at this point only, perhaps as an anchor for a substantial post setting. Outside the main segmented ditch are located two concentric pit/post circles which continue, at least partly, within the eastern annex. A series of less distinct anomalies present to the west of ME026-033 has been named by Condit and Keegan (Reference Condit and Keegan2018, 58–62; figs 53–7) as ‘the Hidden Henge’; they consider these to form part of another large post-built enclosure. However, the exact nature of these features remains unclear and fragmentary.

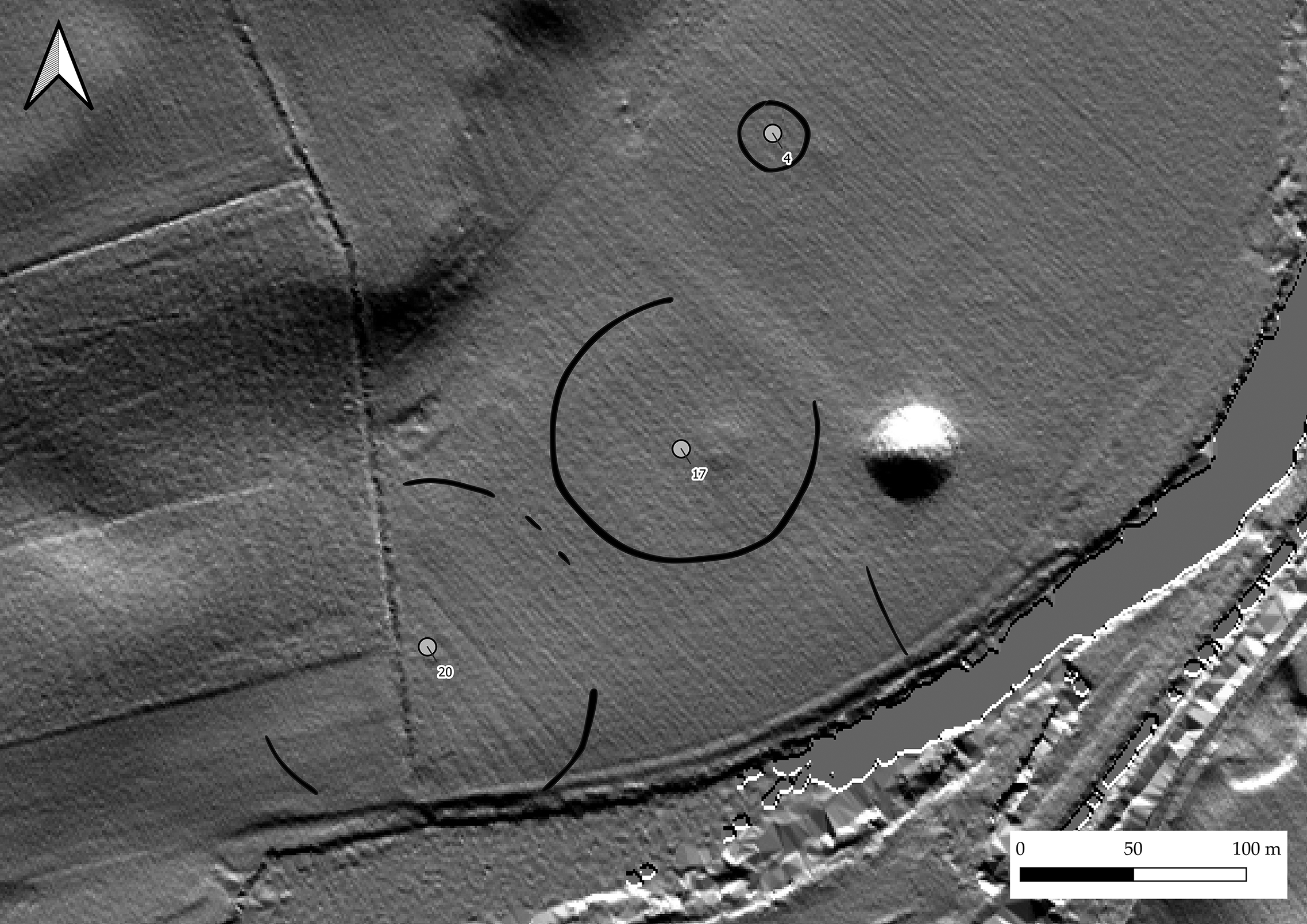

Another cluster of sites has been identified c. 400 m to the east of Site P, adjacent to the probable passage tomb of Site B (Fig. 6). The low mound of Site B1 is located off-centre within a very low-profile embanked enclosure, first identified from LiDAR in 2010 (Davis et al. Reference Davis, Brady, Megarry, Barton, Cowley and Opitz2013). A clear enclosure ditch is evident at this site in the 2018 aerial imagery, positioned external to the previously identified bank. An additional large circular enclosure (‘The Riverside Henge’: Condit & Keegan Reference Condit and Keegan2018) is visible as a cropmark directly south-west of ME019-058002 and 400 m west of Site P: this is the largest of all the Brú na Bóinne enclosures identified to date, with an internal diameter of 154 m. This site displays no evidence of any bank in aerial survey. A smaller enclosure (prosaically named ‘The Small Enclosure’ by Condit & Keegan Reference Condit and Keegan2018) is also visible as a cropmark north-north-east of ME019-058002, where the LiDAR survey shows it to be adjacent to a slight mound. This enclosure is anomalously small for an Irish henge monument and may represent the external ditch of a barrow, a number of which have been identified in geomagnetic survey further east along the river (unpublished data). This close spatial arrangement of an internally embanked site together with an apparently unembanked enclosureFootnote 2 offers a striking parallel to the Welsh sites of Llandegai A and B (Houlder Reference Houlder1968; Lynch & Musson Reference Lynch and Musson2004; Gibson Reference Gibson2012a), the former of which is potentially early in date (Harding Reference Harding2003, 15. NPL-221; 4420±140 bp, 2675–3515 cal bc; median probability 3110 bc; recalibrated with IntCal20: Stuiver et al. 2020). Both ME019-058002 and the Riverside Henge could be considered atypical henges, with Harding (Reference Harding2003) suggesting some of these stylistic traits (eg, external rather than internal bank as at Llandegai A) are likely to be early in the typological sequence of British and Irish henges.

Fig. 6. Presumed passage tomb of Site B, with mound and enclosure of Site B1 (ME019-058002) to west, ‘Small Enclosure’ to north and ‘Riverside Henge’ to south-west. Sites numbered after Table 1 (transcribed from aerial imagery © BlueSky 2018; Anthony Murphy 2020; 32-direction LiDAR hillshade, courtesy of Meath County Council)

HENGE MONUMENTS IN BRÚ NA BÓINNE: GEOPHYSICAL SURVEYS

To date only three of the embanked enclosures/henge monuments within Brú na Bóinne have been subject to geophysical survey using modern methods: ME019-094 (Site LP2; ‘Univallate Henge’), ME019-103 (Site LP1), and Dowth Henge (Davis et al. 2012; Davis Reference Davis2013), with additional survey also covering the area of the Newgrange Pit Circle. The ‘Pit Circle’, excavated in part by O’Kelly et al. (Reference O’Kelly, Cleary, Lehane and O’Kelly1983) and Sweetman et al. (Reference Sweetman, O’Sullivan, Gunn, Monk, Donnabháin and Scannell1985), has been interpreted by Sweetman (1997) as comparable to British henge monuments, despite its perimeter being comprised entirely of pits/post-holes. Geophysical surveys within Stout’s (Reference Stout1991) review, while innovative at the time, are not of sufficient spatial resolution to provide useful archaeological information.

At ME019-094 the slightly flattened ditch outline is clearly evident in the geomagnetic survey (Davis et al. Reference Davis, Brady, Megarry, Barton, Cowley and Opitz2013, 230), although the segmented form that is apparent in the aerial imagery is not clearly visible, but hinted at with the benefit of hindsight (Fig. 7). The most striking feature here is a NNE–SSW oriented linear anomaly within a central high resistance area. This is likely to represent a cut feature within the footings of a central mound. Given parallels with ME019-058002 and with Site A where probable passage tombs are enclosed by henge monuments this may represent the remains of a denuded passage tomb.

Fig. 7. ME019-094 (Site LP2) Transcribed geomagnetic data (with white outline) overlying transcribed 2018 aerial imagery. Central shaded area represents limits of high resistance anomaly (geomagnetic survey, Kevin Barton; aerial imagery © BlueSky 2018, red channel only)

A further enclosure, ME019-103, initially described as Site LP1 (Davis et al. Reference Davis, Brady, Megarry, Barton, Cowley and Opitz2013; Fig. 1, Site 19; Fig. 8) is located c. 500 m north-east of Site B. Here, geophysical survey revealed weakly magnetic ditches both internal and external to the broad bank. These are not visible to the south where they may have been destroyed. To the east the monument is partly overbuilt by a small circular enclosure, which forms part of a substantial complex of probable later prehistoric features that extends east-north-east from here for almost a kilometre. This mirrors the situation noted by Gibson (Reference Gibson2010, 245) at Dyffryn Lane, Pembrokeshire where the site remains a focus for ritual activity even after the construction of its closing central mound.

Fig. 8. ME019-103 (Site LP1), transcribed geomagnetic survey showing internal and external ditches, absent to south. Complex of enclosures obscuring eastern perimeter (LiDAR 32-direction hillshade, data courtesy of Meath County Council)

At Dowth Henge, multiple phases of geomagnetic survey have identified broad ditches both inside and outside the main enclosure (Davis Reference Davis2013; Fig. 9). These appear to show clear interruption at both entrances, suggesting that these are both original features. Some confusion has arisen because of the construction of an ornamental 18th century ‘tree ring’ blocking the north-eastern entrance, the removal of which has caused extensive disturbance. The geomagnetic data shows berms both inside and outside the henge bank. For most of the perimeter the internal and external berms are comparatively narrow (c. 5 m); however, the external berm broadens to 12 m approaching the south-western entrance/egress (Davis Reference Davis2013).

Fig. 9. Dowth Henge and wider area, transcribed geomagnetic data. ME020-083 visible to west of henge (LiDAR 32-direction hillshade courtesy of Meath County Council overlain by Local Relief Model, courtesy of Ralf Hesse)

Within the henge enclosure, in addition to at least one roughly circular central pit or post arrangement, a pair of large pits or post-holes spaced 4.5 m apart is located directly in line with the south-west entrance. Also central within Dowth Henge is a complex collection of elongated pits which may represent the footings of a demolished passage tomb similar to that centrally located within the Giant’s Ring at Ballynahatty, Co. Down (cf. Hartwell 1991; 1998; Reference Hartwell2002; Rassmann et al. Reference Rassmann, Davis and Gibson2019).

A second possible henge, ME020-083 (recorded in the SMR as a ring barrow), measuring 46 m in diameter with a broad internal ditch has been identified at Dowth, 200 m west of Dowth Henge adjacent to a complex of enclosures of unknown date. The most striking aspect of these associated features is a small rectangular structure, one side of which comprises a row of large post-holes, the other, two ‘C’-shaped magnetic anomalies which are likely to represent heavily burned features (Fig. 10). This has obvious similarities to the structure identified by aerial photography at the western entrance of ME026-033.

Fig. 10. Left: Dowth rectangular structure (Fig. 9; transcribed geomagnetic data); right: rectangular structure at western side of ME026-033, same scale (aerial imagery ©BlueSky 2018)

Regional parallels: ME026-033

Segmented-ditch or causewayed enclosures are well-known in the early Neolithic period in Britain (Palmer Reference Palmer1976; Oswald Reference Oswald, Dyer and Barber2001), with ‘formative henges’ (Harding Reference Harding2003; Burrow Reference Burrow, Leary, Darvill and Field2010) such as Flagstones, Dorset (Woodward Reference Woodward1988; Healy Reference Healy1997) and Stonehenge Phase 1 (Darvill Reference Darvill2006, 97; Darvill et al. Reference Darvill, Marshall, Parker-Pearson and Wainwright2012) sharing a similar construction technique with these earlier monuments. Similarly, some large henge enclosures such as the Ring of Brodgar (Downes et al. Reference Downes, Richards, Brown, Cresswell, Ellen, Davis, Hall, McCulloch, Sanderson, Simpson and Richards2013, 110) and Mount Pleasant (Linford et al. Reference Linford, Linford and Payne2019; Greaney et al. Reference Greaney, Hazell, Barclay, Ramsey, Dunbar, Hajdas, Reimer, Pollard, Sharples and Marshall2020) appear to continue this tradition of irregular segmented ditches into the late Neolithic. There is still some debate as to the validity of ‘formative henge’ as a site type, in particular with the chronological implications of the word ‘formative’ – implying that these pre-date conventional henge monuments (Gibson 2012). Given this lack of clarity it might be more prudent to describe these as ‘atypical henges’.

A number of the Boyne monuments likely belong in this atypical group. The extreme regularity and uniformity of the short double ditch segments of ME026-033 finds no clear parallels in either the British or Irish Neolithic, aside from its neighbour ME019-094, which has single regular segments of the same form. The angular form to the north of ME026-033 may argue for the ditches having been dug in gangs rather than as a single unified project, as has been suggested in causewayed enclosures (Startin & Bradley Reference Startin, Bradley, Ruggles and Whittle1981).

There are many parallels for henge monuments enclosing either stone or timber settings; however, the motif of a ditch within a palisade is unusual (Gibson Reference Gibson, Cleal and Pollard2004), although a timber circle was constructed around the small henge at Forteviot (Henge 1; Brophy & Noble Reference Brophy and Noble2012) and Milfield North was surrounded by a ring of pits (Harding Reference Harding1981). If the palisade at ME026-033 is viewed as a precursor to bank construction, mirroring as it does the position of the earthen bank at Site P, then parallels could also be drawn with British sites where sub-bank enclosures have been identified. These include Meini Gwyr, Carmarthenshire (cf. Darvill & Wainwright Reference Darvill and Wainwright2003, 36–8) where geophysical survey revealed a series of pits/post-holes described by the authors as ‘more or less under the centre of the bank’ (ibid., 29) and Blackshouse Burn, Lanarkshire where the largely stone bank overlay and incorporated a timber palisade, dating to the later Neolithic (GU-1983; 4035±55 bp; 2864–2410 cal bc; Lelong & Pollard Reference Lelong and Pollard1998; recalibrated using IntCal20; Stuiver et al. 2020). Recent research at Durrington Walls (Gaffney et al. Reference Gaffney, Neubauer, Garwood, Gaffney, Löcker, Bates, Smedt, Baldwin, Chapman, Hinterleitner, Wallner, Nau, Filzwieser, Kainz, Trausmuth, Schneidhofer, Zotti, Lugmayer, Trinks and Corkum2018, 264–6) has also demonstrated that an earlier monument comprising a series of substantial post-holes was overbuilt by and perhaps formalised by the construction of the later earthen henge enclosure.

EMBANKED ENCLOSURES & STRUCTURAL DEVELOPMENT

From the range of earthworks preserved and evidence from aerial and geophysical survey it is possible that some of the enclosures in Brú na Bóinne were only ever surrounded by low banks and that the raising of banks to form substantial earthworks was limited to only a few monuments. However, once again excavation is required to understand fully the sequence of development at these sites.

At Site ME019-094 (Site LP2; Fig. 7) geophysical survey and aerial photography imply the monument had very insubstantial banks only, the external parchmark suggesting a bank width of c. 6.5 m, comparable to the outermost parchmark at Site P. At ME026-033 there is no evidence that the monument was ever embanked; the same is true of the ‘Riverside Henge’. It is suggested that where banks did occur they existed at most in the form of Collins’s (Reference Collins1957) outer gravel ‘guide enclosure’, most likely representing an early structural phase. While these enclosures are clearly delimiting space, they are unlikely for the most part, to be controlling any visual aspect of the landscape nor could they have done so without significant additional timber construction. An exception to this is Dowth Henge which, owing to its elevated position and substantial banks, offers a truly enclosed space, visually isolated from the outside world.

Site P and ME026-033 possess a remarkable degree of similarity to one another (Fig. 5) and differ principally in that Site P is enclosed by at least two phases of earthen bank while ME026-033 is likely to have instead been enclosed by timber uprights, perhaps planked or connected with screens. It is also possible that the segmented ditches at this site could have held short lengths of palisade or planking. The bank at Site P may effectively be formalising the double post enclosure seen at ME026-033. The principal difference is with the structure of the annex: at Site P this is preserved as an earthen rampart while at ME026-033 the post circuits run within the segmented ditch which defines the innermost boundary of the annex. Dowth Henge sees still further elaboration in the form of more significant internal and external ditches, two clear and opposing entrances, and substantial raised banks. This may imply that it falls late in the construction sequence of henges in Brú na Bóinne, in keeping with generally accepted dating evidence within a British context (Gibson Reference Gibson2012a, 13–20), or that Dowth Henge has undergone significant modification and embellishment since its original construction.

As regards formal access to the interior of these enclosures, at the Newgrange Pit Circle, Site P, ME026-033 and at Dowth Henge, there are clearly formalised points of access/egress. At Sites P and Dowth Henge there are two apparent openings; however, in some cases the boundaries are essentially permeable at any point without palisading and planking. It may be that, as at the western opening of Site P, these formal access points exist but are unelaborated and potentially very narrow, or that they have been deliberately blocked upon the site’s abandonment (cf. Brophy & Noble Reference Brophy and Noble2012).

From currently available data it is impossible to say how many of the Brú na Bóinne henges were in concurrent use (or indeed, what or when that use might have been); however, the large number of these sites in close proximity suggests that perhaps each was used for a limited period only rather than them all being constructed and in use simultaneously. In terms of palisaded structures, these would have had a finite lifespan. The frequently-cited estimate of Wainwright and Longworth (Reference Wainwright and Longworth1971, 224–5) of a rate of wastage of 15 years per inch for oak posts means that without replacement of posts it is likely that an enclosure of this type would be in substantial disrepair within a few centuries at most. Beyond this lifespan perhaps some of these monuments were further commemorated by the raising of significant earthen banks, emphasising the line of the former palisade.

TIMBER ARCHITECTURE: LATE NEOLITHIC/EARLY BRONZE AGE FOUR-POSTER STRUCTURES

Aerial and geophysical surveys to date have identified at least six four-poster or ‘square-in-circle’ monuments within Brú na Bóinne (Fig. 11), in addition to the ones excavated at Knowth (Eogan & Roche Reference Eogan and Roche1994) and possibly at Newgrange (Sweetman et al. Reference Sweetman, McCormick and Mitchell1987). One of these has recently been identified through aerial survey (ME019-067002; K. Williams pers. comm.; Condit & Keegan Reference Condit and Keegan2018, 25–32), with the other five identified through large-scale geomagnetic survey. Most of these monuments are in the area between Knowth and Newgrange and all are aligned in an easterly or south-easterly direction (Table 2). These have been referred to as possible mortuary enclosures (eg, Hartwell Reference Hartwell1991, 11; Condit & Keegan Reference Condit and Keegan2018, 25) although interpretation of them is still very much a matter for debate (see discussion in Carlin & Cooney Reference Carlin, Cooney, Stanley, Swan and O’Sullivan2017).

Fig. 11. Brú na Bóinne four-poster structures drawn to same scale. 1. Knowth four-post structure, excavated outline (redrawn after Eogan & Roche Reference Eogan and Roche1994); 2. ME019-067002 (transcribed from aerial image); 3. DOW61; 4. NG39; 5. NG10; 6. NG16 (transcribed from geomagnetic data)

TABLE 2: APPROXIMATE DIMENSIONS AND AZIMUTH OF FOUR-POST STRUCTURES IN BRÚ NA BÓINNE

In all cases the central four-post setting is laterally compressed.

ME019-046005 excluded as it is not possible to determine dimensions of either four-post setting or azimuth.

In addition to the common motif of a central rectangular setting that would have comprised four substantial posts, all display a degree of enhancement on one side, usually including a pair of post-holes or pits and possibly reflecting an entrance arrangement. In the excavated example at Knowth, this comprises an eastern post-built ‘porch’ (Eogan & Roche Reference Eogan and Roche1994) or embellished façade, with ME019-067002 and NG10 also showing evidence of extended entrance avenues to the east and south-east respectively. Elsewhere in Ireland such aggrandisement of the eastern and south-eastern sides of monuments of this period has also been noted (eg, Ballynahatty; Hartwell 1998; Reference Hartwell2002; Balgatheran, Co. Louth; Ó Drisceoil Reference Drisceoil2009). The enhancement of entrance features seen at these sites could be considered analogous with the annex structures seen at Site A, Site P and ME026-033 (Fig. 12).

Fig. 12. Left: Knowth four-post structure (redrawn from Eogan & Roche Reference Eogan and Roche1994); right: ME026-033 – eastern annex (transcribed from aerial photography)

In ME019-067002 the post-circle is doubled, with a parchmark between the two circuits suggesting the presence of a bank. This monument appears to be enclosed by a closely-spaced oval palisade c. 95 m in diameter (Condit & Keegan Reference Condit and Keegan2018, 29). DOW61 and NG39 also appear to possess a double circuit of posts although only the façade is visible in geomagnetic survey. This suggests the inner post-ring may have been burned or have burned material incorporated into its fill, as at Ballynahatty (Hartwell Reference Hartwell1998). This is also the case at the partially excavated Western Circle at Newgrange (Sweetman et al. Reference Sweetman, McCormick and Mitchell1987, 291), where none of the outer (Group 4) post-holes included packing stones or larger pieces of charcoal. As at ME019-067002, DOW61 appears to be set within a larger enclosure and possesses traces of an unusual ‘double-ditched entrance’ feature (see Fig 17), discussed further below.

The final example of these four-post structures (NG16) represents a greatly embellished form. This large, circular enclosure appears to be open to the east, facing towards Newgrange (Figs 11 & 13) and may have an opposing entrance to the west (Rassmann et al. Reference Rassmann, Davis and Gibson2019). The central area comprises two parallel short settings of pits or post-holes, oriented in a north-west to south-east direction and enclosing a secondary arrangement of smaller pits/post-holes. To the north-west of these lie two large pits or post-holes, mirrored at Balgatheran Building 3 among other sites (see Ó Drisceoil Reference Drisceoil2009, 94; Smyth Reference Smyth2014, 88) which, along with the central setting, create a defined axis of symmetry. To the south-east are traces of up to three concentric rings of pits or post-holes, flattened to this direction. This is paralleled in ME019-067002 and also at BHN6 at Ballynahatty where the excavated post-holes towards the entrance area were packed with burned material and charcoal (Hartwell Reference Hartwell1998). The four-post arrangement at NG16 measures 18.2 × 16.5 m, approximately 1.5 times the size of any other similar structure in Ireland. Externally NG16 is surrounded by several highly magnetic anomalies, perhaps large post-holes or stone sockets, similar to outliers in a stone circle. This ‘lithicisation’ of timber settings has also been noted at Stanton Drew SSW (Fig. 13; David et al. Reference David, Cole, Horsley, Linford, Linford and Martin2004), Machrie Moor (Haggarty Reference Haggarty1991), and on a smaller scale at Knowth (Eogan & Roche Reference Eogan and Roche1997, 103). Preliminary archaeo-astronomical assessment (Frank Prendergast pers. comm.) suggests the central setting of NG16 is, like Newgrange, aligned on the winter solstice sunrise. While the east–west orientation of the external ditch is shared with the ‘Great Linear Palisade’ (see below) and, as noted by Leigh et al. (Reference Leigh, Stout and Stout2018), closely aligns on the spring and summer equinox sunrises, this may be a consequence of its position relative to Newgrange as opposed to a deliberate astronomical trait (cf. Ruggles Reference Ruggles1997).

Fig. 13. Newgrange Site NG16 (transcribed geomagnetic data) compared with SSW circle at Stanton Drew; identical scale (redrawn after David et al. Reference David, Cole, Horsley, Linford, Linford and Martin2004)

Regional parallels: Newgrange Site NG16

The architectural motif of squares within circles has been elaborated upon in detail elsewhere (eg, Pollard Reference Pollard2012, 100–2). Likewise, late Neolithic four-post structures have been reviewed elsewhere in both Scotland (Noble et al. Reference Noble, Greig, Millican, Anderson, Clarke, Johnson, McLaren and Sheridan2012) and in Ireland (in Brophy Reference Brophy, Brophy, MacGregor and Ralson2016, 217–20; Smyth Reference Smyth2014; Carlin & Cooney Reference Carlin, Cooney, Stanley, Swan and O’Sullivan2017, 42–6).

The scale and complexity of the Newgrange site sets it apart from other four-post structures thus far recorded within Ireland and Scotland. However, geophysical survey at the SSW circle at Stanton Drew (David et al. Reference David, Cole, Horsley, Linford, Linford and Martin2004; Linford et al. Reference Linford, Linford and Payne2018) provides a close parallel. Here, the outer stone circle (c. 44 m diameter) encloses three concentric rings of magnetic anomalies, interpreted as pits filled with ‘magnetically enhanced material’ (Fig. 13; David et al. Reference David, Cole, Horsley, Linford, Linford and Martin2004, 350). The Stanton Drew enclosure incorporates a series of larger anomalies on the boundary of the outermost ring, four of which form a large square setting with sides measuring c. 17 m in length. Further anomalies to the north-east create an axis of symmetry, as seen in some Irish four-post structures (see Smyth Reference Smyth2014, 88).

Another possible parallel can be seen at Coneybury Henge, Wessex (Richards Reference Richards1990, 123–58; 259; Pollard Reference Pollard2012, 102). Here, a central linear setting of six post-holes and associated shallow features was excavated, with an additional two, more closely spaced post-holes apparently ‘flanking the axis of symmetry’ of the central setting (Richards Reference Richards1990, 137), in this case directly aligned with the entrance of the enclosure to the east. The central setting at Coneybury was surrounded by a ring of shallow post-holes. Based on ceramic evidence, Ellison (Reference Ellison1990, 149) suggests that the enclosure at Coneybury post-dates the central setting. It is notable that these two parallels belong not to the Irish or Scottish corpus, but to southern England.

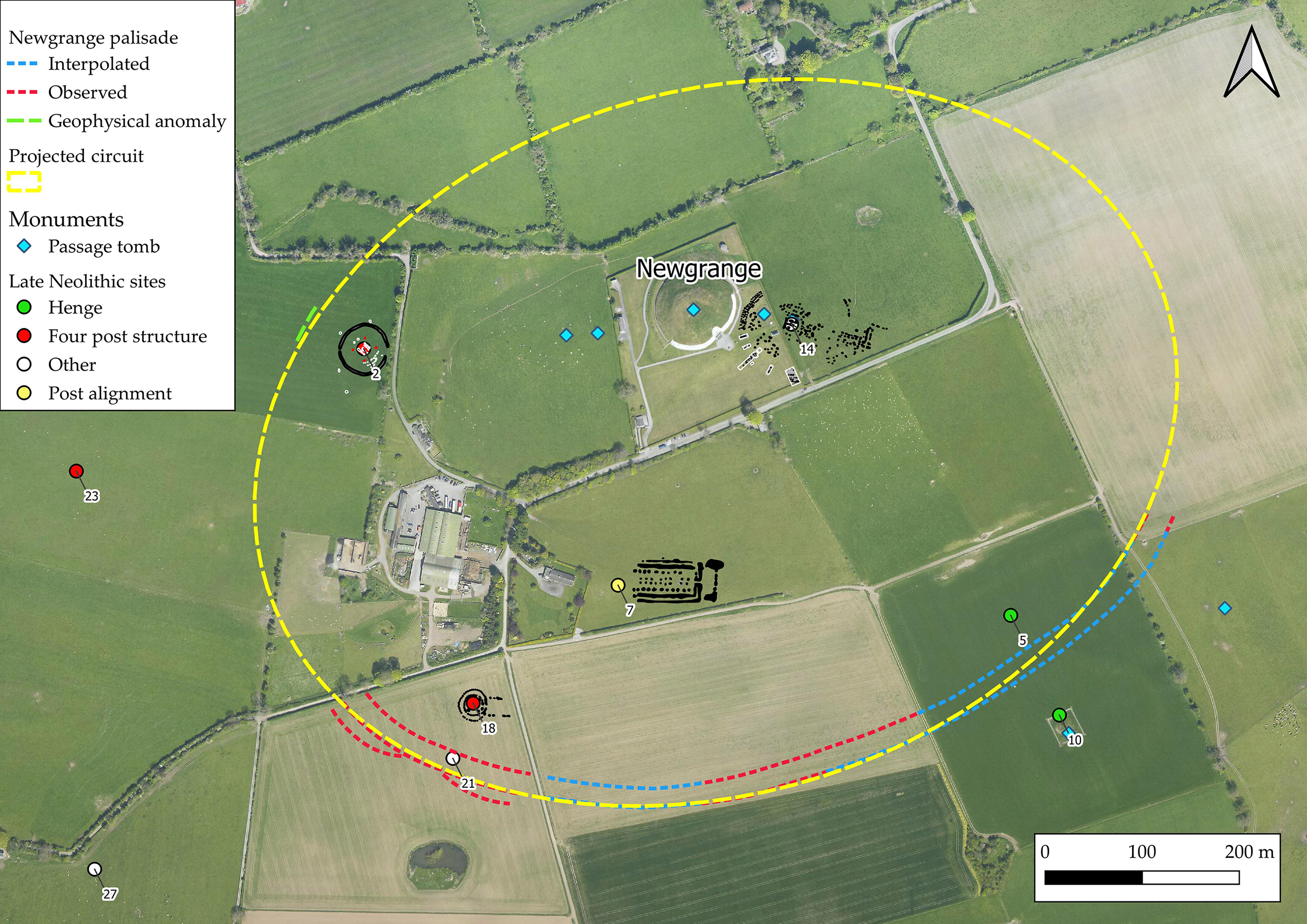

TIMBER ARCHITECTURE IN BRÚ NA BÓINNE: PALISADED ENCLOSURES

As well as the earthen enclosures identified or confirmed by aerial survey in 2018 perhaps the most remarkable discovery was an enormous palisaded enclosure that appears to enclose a large part of the Newgrange precinct (Figs 14 & 15). Dubbed by Condit and Keegan (Reference Condit and Keegan2018, 33) ‘The Great Palisade’, they suggest this could form a triple-palisaded enclosure approximately 900 m on its long axis with a post spacing of 1.5–2 m. A short section of palisade with similarly spaced magnetic anomalies is visible due west of Newgrange, potentially encompassing site NG16. The visibility of some sections of this palisade within the geomagnetic survey perhaps echoes the situation at Mount Pleasant where some portions of the palisade were destroyed by fire (Wainwright Reference Wainwright1979, 240).

Fig. 14. Newgrange and the ‘Great Palisade’. Circuit marked in red is recorded within aerial imagery; blue interpolated; green section visible in geomagnetic survey. Dashed yellow line is a projection of potential entre circuit (aerial imagery ©BlueSky 2018)

While Neolithic palisaded enclosures are well-documented from Britain (Whittle Reference Whittle1997; Gibson Reference Gibson1998a; Reference Gibson1998b; Reference Gibson, Cleal and Pollard2004; Hale et al. Reference Hale, Platell and Millard2009; Noble & Brophy Reference Noble and Brophy2011; Millican Reference Millican2016, 47–52) and to a lesser extent Ireland (Grogan & Roche Reference Grogan and Roche2002), the scale of this monument is exceptional. Again, detailed discussion is hampered by a lack of excavation and hence chronological control: in scale and complexity the only other parallels in Ireland are the Iron Age earthworks of The Dorsey and the Black Pig’s Dyke, gigantic palisaded earthworks, the function of which remains enigmatic (Lynn Reference Lynn1977; Hurl & McSparron Reference Hurl and McSparron2004). While the focus of the Newgrange palisade on so significant a Neolithic complex might argue for a late Neolithic date, there is considerable evidence of Iron Age activity within Brú na Bóinne (eg, Eogan Reference Eogan1968, 365–73; Reference Eogan1974, 68–87; Reference Eogan2012; Carson & O’Kelly Reference Carson and O’Kelly1977; Bendry et al. Reference Bendrey, Thorpe, Outram and Wijngaarden-Bakker2013) and the idea that monuments might have been either modified or constructed during this period can certainly not be discounted.

The only Neolithic palisaded enclosure of comparable size across Britain and Ireland is Hindwell in Wales, with approximate dimensions of 880 m east–west by 540 m north–south and enclosing an approximate area of 34 ha (Gibson Reference Gibson1998a). It is significantly smaller than the projected area of the Newgrange enclosure (55 ha). Considering that Hindwell itself is perhaps four times the size of its nearest rival (ibid., 76), this represents timber monumentality on a massive scale and complexity. At Hindwell, for a single circuit of palisade, Gibson (Reference Gibson1999, 154) estimates construction materials in the order of 1410 posts and 6300 tonnes of oak. He also suggests that enclosures of this type, where posts are not contiguous, are likely to have been planked in order to effectively manage access to the interior, assuming this was an important part of their function. This would require further significant timber resources. The origin of such prodigious quantities of timber remains unclear but it is unlikely to have been available from within the immediate area of Brú na Bóinne (Davis Reference Davis2017). As such, its felling, splitting, and transport to site may well have been as monumental a task as that of quarrying and moving orthostats and kerbstones in previous generations.

The closest parallels to the massive Newgrange enclosures in the Irish Neolithic are the timber structures at Ballynahatty, Co. Down (Hartwell Reference Hartwell1998); these incorporate some features that closely resemble those evident at Newgrange albeit on a far smaller scale. The large, double-circuit four-post timber enclosure of Ballynahatty BHN6 is mirrored by the similar, although larger structure ME019-067002 at Newgrange. At Ballynahatty, this lies off-centre within the double oval timber palisade of BHN5, in the same manner that ME019-067002 lies off-centre within the likely circuit of the Newgrange palisades. The projected triple-palisaded enclosure, while incorporating Newgrange and ME019-067002 apparently intersects both the henge at Site A and the Newgrange cursus. It is possible that the point of intersection with Site A is responsible for the scarping of this enclosure noted to the north-west by Davis et al. (Reference Davis, Brady, Megarry, Barton, Cowley and Opitz2013).

While Hale et al. (Reference Hale, Platell and Millard2009, 286) highlight that in many cases palisaded enclosures are overlooked by large Neolithic mounds, in this case it would seem possible that the triple palisade extends to actually enclose the mound of Newgrange in addition to a substantial area around the tomb. Elsewhere within Brú na Bóinne the enclosure of passage tombs is a common motif but the palisade here would enclose not just a single tomb but an entire precinct, potentially delimiting an enormous ceremonial space between Newgrange and the river. This idea is possibly echoed in the enclosing ramparts described by Bergh (Reference Bergh2000) at Knocknarea, Co. Sligo, where the entire plateau appears to have been enclosed by earth and stone banks. Similar large precincts appear to have been defined at some Irish ‘Royal’ sites, in particular at Rathcroghan, Co. Roscommon (Waddell et al. Reference Waddell, Fenwick and Barton2009) and Uisneach, Co. Westmeath (Schot Reference Schot, Schot, Newman and Bhreathnach2011), again unexcavated and undated, but associated with probable later prehistoric landscapes.

TIMBER ARCHITECTURE IN BRÚ NA BÓINNE: LINEAR POST ALIGNMENTS

At least four linear post alignments have now been recorded in the wider area, including one each at Dowth and Oldbridge to the south side of the river and two examples at Newgrange (Fig. 16). While published in a preliminary form (Smyth Reference Smyth2009, 22), no high-quality image of the geomagnetic survey from the Newgrange Pit Circle/cursus area is currently available for analysis. The pit circle itself is not clearly visible in the available geomagnetic data; however, a double pit or post-alignment is evident running in a north-west to south-east direction and terminating to the south-east in a perpendicular double pit or post row. At the north-west end of the post alignment are two short parallel pit or post-rows, potentially with some indications of burning. Part of a possible fifth post alignment was partially excavated by O’Kelly south-west of Newgrange (O’Kelly et al. Reference O’Kelly, Cleary, Lehane and O’Kelly1983), although the location of this at the western limit of his excavation area and the lack of dating evidence hampers detailed interpretation.

Fig. 15. Detail of the ‘Great Palisade’ showing three palisade circuits (aerial image courtesy of Anthony Murphy, May 2020)

Fig. 16. Linear post alignments, Brú na Bóinne: clockwise from top left: ME019-129 (‘Great Rectangular Palisade’) (transcribed resistivity data after Leigh et al. Reference Leigh, Stout and Stout2018, LiDAR data with Local Relief Model. Projected features in grey); Newgrange Pit Circle (transcribed geomagnetic survey after Smyth Reference Smyth2009); Oldbridge pit/post alignment OLD12 (transcribed geomagnetic survey); Dowth pit/post alignment DOW19 (transcribed geomagnetic survey)

The Oldbridge alignment occupies an elevated position on the south side of the Boyne. It comprises two parallel rows of regularly spaced pits or post-holes which extend for c. 40 m in a north-west to south-east direction. The central pits/post-holes are enclosed within a weakly magnetic rectilinear feature. This alignment has clear similarities with those identified at Newgrange and Dowth. It may also be analogous with an undated structure excavated at Ballingowan, Co. Kerry (Moloney Reference Moloney2013; Long et al. 2020, 39–42, 95–7) and bears a striking similarity to the undated Scottish free-standing timber avenues reviewed by Millican (Reference Millican2016, 41–3).

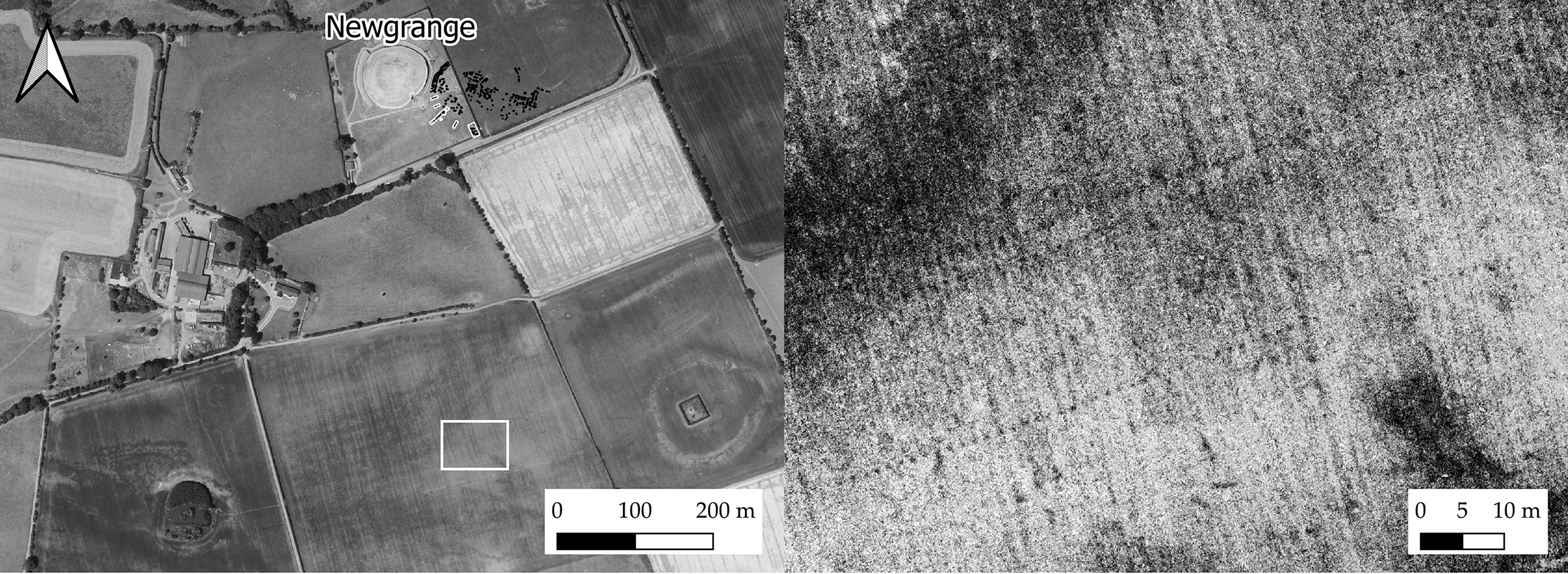

The most remarkable of these linear structures was discovered through geophysical survey in 2015, extending for almost 200 m east–west on a low ridge beneath the main shale outcrop on which Newgrange stands (Leigh et al. Reference Leigh, Stout and Stout2018; Fig. 16). Briefly, the structure comprises two parallel rows of regularly spaced pits or post-holes, larger ones to the outside (5–7 m apart), smaller to the interior (4.5–5 m apart), enclosed within a regular double rectilinear enclosure. A narrow entrance feature, c. 3 m across is located to the east. A second probable post-built linear feature runs north–south, perpendicular to the long axis of the structure and perhaps controlling access to the entrance. Recent test excavations yielded a preliminary date of 2829–2468 cal bc from oak charcoal (heartwood) recovered from the basal fill of the outer ditch (UBA-38707; 4034±33 bp; Leigh et al. Reference Leigh, Stout and Stout2019; recalibrated using IntCal20; Stuiver et al. 2020); two further radiocarbon dates on animal bone were attempted but failed owing to poor collagen preservation (Matthew Stout pers. comm.). Given the nature of the material available for selection this date should obviously be treated with a degree of caution. Although this monument has been described as a ‘hybrid cursus’ (Leigh et al. Reference Leigh, Stout and Stout2019), the late Neolithic date and internal partitioning make it unlike other cursus monuments. While cursus monuments in Ireland are very much under-researched (Corlett Reference Corlett2014; Kenny Reference Kenny2014) and unexcavated, none of those so far identified has evidence for internal pits, double ditches, or a façade.

These post alignments most likely represent ceremonial avenues: both the Dowth example and that associated with the Newgrange Pit Circle are closely associated with both passage tombs (Site Z; the recently discovered tombs at Dowth Hall) and henge monuments (eg, Dowth Henge) or henge-like structures (the Newgrange Pit Circle). Post alignments are recorded within a number of significant late Neolithic landscapes in Britain and Ireland; however, in some ways they mirror discussion of henge monuments in that the one thing that is agreed upon is that they are ‘extremely heterogeneous’ (Waddington Reference Waddington1997, 22) and are associated with ‘a range of features of varying date’ (ibid., 24). The earliest dated examples, like the Newgrange site, date from the late Neolithic and appear to be associated with Grooved Ware activity (ibid., 29–30; Harding Reference Harding2013, 136–7), although similar monuments seem to have been constructed well into the Bronze Age (Millican Reference Millican2016, 41–2).

Two of the linear monuments described (Newgrange Pit Circle and Great Rectangular Palisade) also possess what could be termed ‘double linear’ entrances, comprising two linear ditch/palisade sections perpendicular to the direction of the alignment, each with a narrow, well-defined entrance. Two other similar features have been identified within the Brú na Bóinne geomagnetic surveys, one of which (DOW62) is associated with the four-post structure DOW61 (Fig. 17). It seems likely that these entrance features are formalising the approach to certain structures, perhaps controlling access to important sites.

Fig. 17. Double linear entrance features: clockwise from top left: NG51; DOW62 (transcribed from geomagnetic survey); ME019-129 (‘Great Rectangular Palisade’: redrawn after Leigh et al. Reference Leigh, Stout and Stout2018); Newgrange Pit Circle (transcribed from geophysical survey in Smyth Reference Smyth2009)

LATE NEOLITHIC ARCHITECTURE IN BRÚ NA BÓINNE: A COMMONALITY OF MOTIFS

As has been strongly argued elsewhere (Carlin Reference Carlin2017, 176–81) there are significant architectural commonalities between later Neolithic enclosures and the passage tombs that preceded them. In the case of ME026-033, Newgrange itself offers an obvious parallel: both have axial symmetry and significant aggrandisement to the front and the rear, with the elaborate entrance stone and the highly decorated opposing Kerbstone 52 at Newgrange mirrored by the annex and rectangular structure at ME026-033. Moreover, the idea of discontinuous boundaries, such as is evident at both ME019-094 and ME026-033, is most clearly demonstrated in the orthostatic passage tomb kerbs themselves and, at Newgrange, by the Great Stone Circle, although this is considered to be later in date than the pit circle (Sweetman et al. Reference Sweetman, O’Sullivan, Gunn, Monk, Donnabháin and Scannell1985, 208–9; Carlin Reference Carlin2017, 178). This stresses the idea that these sites are, at least in part, re-imaginings of stone structures in timber and earth.

Newgrange site NG16 also incorporates many of the same architectural motifs seen at Newgrange passage tomb. Here, the enclosing ditch mirrors a stone kerb, while centrally a timber ‘passage’, aligned on the winter solstice sunrise has clear parallels in the orthostatic passage of Newgrange. The circular post settings within the enclosure provide the concentricity or ‘wrapping’ evident in the design of Irish passage graves (Robin Reference Robin2010; Richards & Cummings Reference Richards, Cummings, Cummings, Hofmann and Pollard2017). Darvill (Reference Darvill2010, 4) describes the barrow at North Mains (Barclay Reference Barclay1983) as ‘essentially a timber passage grave’: this seems a very appropriate description for some elements of the Newgrange structure, although chronology clearly remains a major issue and one that is only really possible to address through excavation.

Spatially, the Boyne four-post structures appear to be more within the domain of passage tombs than henge monuments: the recorded examples to date do not extend to the lowest floodplain terraces where most of the henges are located but are instead located in elevated areas, visible from the river. Questions of the domestic or ritual nature of these sites have been extensively discussed (eg, Sheridan Reference Sheridan, Roche, Grogan, Bradley, Coles and Raftery2004, 29; Smyth Reference Smyth2011, 22–3; Noble et al. Reference Noble, Greig, Millican, Anderson, Clarke, Johnson, McLaren and Sheridan2012, 151–8; Brophy Reference Brophy, Brophy, MacGregor and Ralson2016). Increasingly these are interpreted as ‘monumentalised versions of people’s homes’ (Carlin & Cooney Reference Carlin, Cooney, Stanley, Swan and O’Sullivan2017, 46), although the idea of a straightforward division between ceremonial and domestic life and architecture in the late Neolithic is generally recognised to be a gross oversimplification (eg, Noble et al. Reference Noble, Greig, Millican, Anderson, Clarke, Johnson, McLaren and Sheridan2012, 167; Thomas Reference Thomas2015, 154; Carlin & Cooney Reference Carlin, Cooney, Stanley, Swan and O’Sullivan2017, 41–6).

The post alignments, especially ME019-129, while superficially cursus-like and perhaps having a similar ceremonial function, have their clearest parallels in rectangular building architecture although the scale of these structures at Brú na Bóinne probably precludes the possibility of them ever having been roofed. These similarities are at their most apparent in extended ‘piered’ structures within Orkney (eg, Structure 8 at the Ness of Brodgar) and in Orcadian stalled cairns (eg, Callandar & Grant Reference Callandar and Grant1934; Fig. 18), representing in elongated form the same parallels often drawn between Skara Brae type house architecture and four-post structures (Bradley 2007, 118–26; Reference Bradley2013). Parallels can be drawn between this design and the late 3rd millennium timber structures excavated at Balfarg, Fife, interpreted by Barclay and Russell-White (Reference Barclay and Russell-White1993, 180) as ‘part of the continuum … from the relatively small long mortuary enclosures to the great cursus monuments’, as well as with some early Neolithic long houses, especially from Scotland (eg, Crathes; Murray et al. Reference Murray, Murray and Fraser2009; or Lockerbie Academy; Kirby Reference Kirby2011) although these were constructed almost 1000 years earlier.

Fig. 18. Rectangular architecture in Orkney and Brú na Bóinne: top: Midhowe plan (redrawn from Callander & Grant 1934); Ness of Brodgar Structure 8 (redrawn from Towers et al. Reference Towers, Card and Edmonds2017); Newgrange ME019-129 (‘Great Rectangular Palisade’)

This continuum between cursus monuments, long mounds, long houses, and ‘mortuary enclosures’ has been discussed in detail elsewhere (Bradley Reference Bradley1983; Loveday Reference Loveday1985; Reference Loveday2006; Thomas 1999, 51–2; Reference Thomas2006; Millican Reference Millican2016, 38–40). In the same way that Clare (Reference Clare1987, 462) draws parallels between early Neolithic timber mortuary structures beneath long barrows and timber settings associated with late Neolithic henge monuments, it is likely that these late Neolithic monuments represent ‘a conscious evocation’ of earlier monumental forms (Thomas 1999, 52).

CONCLUSIONS

This paper demonstrates not only the remarkable diversity but also the equally remarkable commonality of some of the motifs related to the probable late Neolithic monument complex within Brú na Bóinne. While many of the architectural themes are conserved between the middle–late Neolithic (as recently discussed by Carlin Reference Carlin2017) there is, as has been discussed elsewhere, a move towards timber and earthen construction rather than building in stone. In the majority of the Boyne enclosures, the control of visual aspects of the landscape seems to be of limited importance: while these enclosures may be delimiting areas of ceremonial activity from areas where such activity did not take place, visually it seems likely that the interior of many of these sites remained connected to the rest of the landscape, the act of enclosure in itself being the primary consideration (Younger Reference Younger2015, 139–42). As regards what was actually being enclosed, in several sites the focus of enclosure would appear to be probable megalithic tombs (eg, Site A; ME019-103; ME019-058002; Dowth Henge); this mirrors the situation at Balregan (Ó Donnchadha & Grogan Reference Ó Donnchadha and Grogan2010), where appreciable quantities of middle Neolithic pottery were recovered in association with the henge ditch: the location of these later Neolithic enclosures is likely to have already been significant prior to their construction.

In the four-post structures some typical passage tomb motifs are very much apparent. At NG16 this not only includes some clear passage tomb cosmology (eg, axial symmetry; concentricity; winter solstice alignment) but is potentially treated in a similar fashion by being ‘henged’, similar to the sequence outlined at Coneybury by Pollard (Reference Pollard2012, 102–3), and potentially ‘lithicised’ as at the Knowth timber circle, Machrie Moor, and arguably Newgrange itself. This treatment echoes the recent views of Carlin (Reference Carlin2017), who stresses the degree of continuity in place and practice evident between the period of passage tomb construction, late Neolithic monumentality, and subsequent Beaker activity. While the smaller four-post structures can be compared to the Scottish monuments reviewed by Noble et al. (Reference Noble, Greig, Millican, Anderson, Clarke, Johnson, McLaren and Sheridan2012), NG16 finds its closest comparisons in southern England (eg, Stanton Drew SSW), perhaps arguing for closer contact between Brú na Bóinne and southern England in the late Neolithic. Similarly, wider regional contacts may in part explain the form of the linear post-built structures: while it is likely that these functioned as ceremonial avenues, they are not cursus monuments in any conventional sense, but have echoes of long mound/long house architecture, insular in design but perhaps reflecting continued contact with Orkney and Mainland Scotland.

As an overall complex, the scale and diversity of the Boyne monuments invites few parallels and appears to represent a mix of broader regional ideas (eg, possible connections to Orkney, mainland Scotland and southern England) mingled with some insular developments in style. Despite this remarkable diversification, the late Neolithic monumentality of Brú na Boinne remains firmly rooted in its megalithic past. Passage tombs are enclosed by henge monuments; post alignments, also aligned on megaliths, echo both earlier cursus monuments and rectangular building architecture; four-post structures reflect a range of architectural motifs familiar from the developed passage tombs of the area. While the Brú na Bóinne passage tomb cemetery clearly represents a period of intense landscape-scale activity in the centuries prior to c. 3000 bc, the activity seen in the post-passage tomb period is hardly less intensive or extensive; however, the changing construction materials (timber and earth) of these post-passage tomb monuments are such that many have only become visible owing to recent survey campaigns.

Clearly there are some obvious and very significant gaps in our knowledge so far as the late Neolithic complex in Brú na Bóinne is concerned, in particular as regards both the chronology and function of these sites. Several key research gaps highlighted within Smyth’s (Reference Smyth2009) World Heritage Site Research Framework are as valid now as they were over a decade ago. Further excavation is sorely needed and it is clear that this review represents only a part of a continuing conversation on the late Neolithic and early Bronze Age monumentality of Brú na Bóinne and its wider regional connectivity.

Acknowledgements:

The authors would like to thank a number of colleagues for helpful discussion, comment, and suggestion, especially Richard Bradley and Alison Sheridan, as well as Muiris O’Sullivan, Geraldine Stout, Neil Carlin, Joanna Brück, and Susan Greaney who provided helpful comments on earlier drafts of this article. We would also like to thank BlueSky International and Meath County Council for the use of aerial and LiDAR data, Ken Williams and Anthony Murphy for allowing the use of their remarkable images, and the landowners of Brú na Bóinne, especially Austin Downey, Pascal and Kevin Hand, Brigid Salmanovic, and Alice and Owen Brennan, for allowing our continued survey campaigns. Early surveys at Sites LP1 and LP2 were funded by the Heritage Council and at Dowth Henge by the Office of Public Works. Thanks are due to Christine Markussen, Chris Carey, Susan Curran, Kevin Barton, and Joanna Leigh for assistance with early geophysical surveys and Conor McDermott for help with figures. The authors are also extremely grateful for the valuable and constructive comments provided by two anonymous referees.