No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

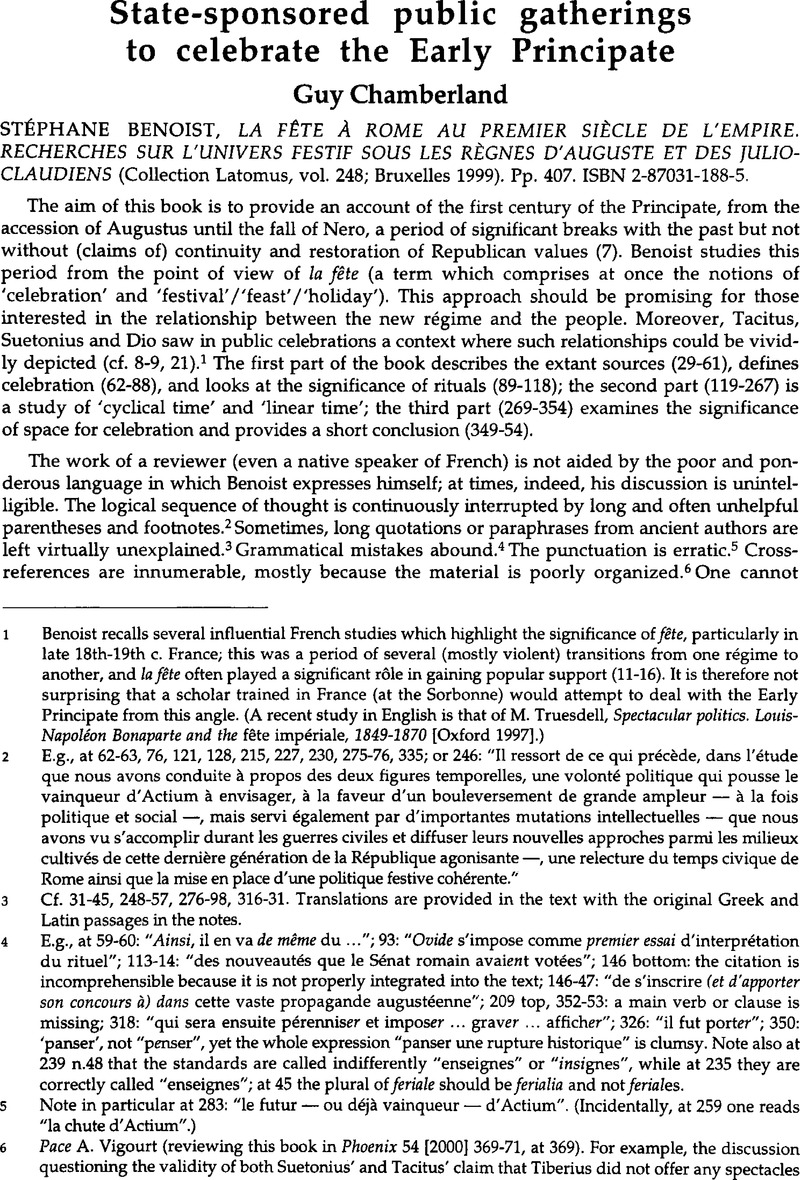

State-sponsored public gatherings to celebrate the Early Principate - Stéphane Benoist, LA FÊTE À ROME AU PREMIER SIÈCLE DE L'EMPIRE. RECHERCHES SUR L'UNIVERS FESTIF SOUS LES RÈGNES D'AUGUSTE ET DES JULIO-CLAUDIENS (Collection Latomus, vol. 248; Bruxelles 1999). Pp. 407. ISBN 2-87031-188-5.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 16 February 2015

Abstract

- Type

- Reviews

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Journal of Roman Archaeology L.L.C. 2002

References

1 Benoist recalls several influential French studies which highlight the significance of fête, particularly in late 18th-19th c. France; this was a period of several (mostly violent) transitions from one régime to another, and la fête often played a significant rôle in gaining popular support (11-16). It is therefore not surprising that a scholar trained in France (at the Sorbonne) would attempt to deal with the Early Principate from this angle. (A recent study in English is that of Truesdell, M., Spectacular politics. Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte and the fête impériale, 1849-1870 [Oxford 1997]Google Scholar.)

2 E.g., at 62-63, 76, 121,128, 215, 227, 230, 275-76, 335; or 246: “Il ressort de ce qui précède, dans l'étude que nous avons conduite à propos des deux figures temporelles, une volonté politique qui pousse le vainqueur d'Actium à envisager, à la faveur d'un bouleversement de grande ampleur — à la fois politique et social —, mais servi également par d'importantes mutations intellectuelles — que nous avons vu s'accomplir durant les guerres civiles et diffuser leurs nouvelles approches parmi les milieux cultivés de cette dernière génération de la République agonisante —, une relecture du temps civique de Rome ainsi que la mise en place d'une politique festive cohérente.”

3 Cf. 31-45, 248-57, 276-98, 316-31. Translations are provided in the text with the original Greek and Latin passages in the notes.

4 E.g., at 59-60: “Ainsi, il en va de même du 93: “Ovide s'impose comme premier essai d'interprétation du rituel”; 113-14: “des nouveautés que le Sénat romain avaient votées”; 146 bottom: the citation is incomprehensible because it is not properly integrated into the text; 146-47: “de s'inscrire (et d'apporter son concours à) dans cette vaste propagande augustéenne”; 209 top, 352-53: a main verb or clause is missing; 318: “qui sera ensuite pérenniser et imposer … graver … afficher”; 326: “il fut porter”; 350: ‘panser’, not “penser”, yet the whole expression “panser une rupture historique” is clumsy. Note also at 239 n.48 that the standards are called indifferently “enseignes” or “msi'gnes”, while at 235 they are correctly called “enseignes”; at 45 the plural of feriale should be ferialia and not feriales.

5 Note in particular at 283: “le futur — ou déjà vainqueur — d'Actium”. (Incidentally, at 259 one reads “la chute d'Actium”.)

6 Pace A. Vigourt (reviewing this book in Phoenix 54 [2000] 369–71, at 369)CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed. For example, the discussion questioning the validity of both Suetonius' and Tacitus' claim that Tiberius did not offer any spectacles (cf. infra) begins at 59 and is completed at 250-51. Cf. also below on chapt. 6, and note that the general conclusion, chapt. 9, is inserted into Part 3.

7 Thus, under 27 August “Volturnalia” is spelled out 6 times according to epigraphic variants. This is appropriate in an epigraphic work such as Degrassi's, but of little use in a monograph.

8 Cf. Bradley, K., “The significance of the spectacula in Suetonius' Caesares ,” RivStorAnt 9 (1981) 129–37Google Scholar. It is Benoist's view that the imperial family “se retrouve à l'origine de la production et de la direction effective de tous les grands événements festifs de la capitale” (62), a very forceful, but unsubstantiated, statement.

9 This is confirmed by the index, 395-97. For a book on fête, one is struck by how little the author has to say on Republican ludi (cf. ibid.), which accounted for 77 days of celebration in the Augustan Principate (cf. Degrassi [op. cit. in text] 372).

10 One is further confused when Benoist claims that circus games (and presumably scenic games?) are “célébrations profanes” (226), even though “«l'amusement», ou plus généralement la Fête,… a toujours revêtu une signification religieuse à Rome” (249).

11 This is also suggested by Augustus' “assaut du temps calendaire” (244), discussed below. At 128 Benoist seems to suggest that celebrations such as the emperor's birthday more properly belonged to linear time, but also that for such celebrations the demarcation between linear and cyclical time was blurred because of the imperial cult; yet this point is not actually discussed.

12 On the legal aspects of the dies imperii, cf. Parsi, B., Désignation et investiture de l'empereur romain (Paris 1963) 125–68Google Scholar; also Brunt, P. A., “Lex de imperio Vespasiani,” JRS 67 (1977) 95–116 Google Scholar.

13 Cf. Wiedemann, Th., Emperors and gladiators (London 1992) 133–34, 173 CrossRefGoogle Scholar; id., CAR 2 vol. 10, 206-7, 215. Tiberius' failure to complete the rebuilding of Pompey's theatre, after the fire of 22, must also be seen as a lack of willingness to invest in spectacle (Suet. Tib. 47, cf. Tac. Ann. 3.72; he apparently completed only the stage [scaena]: Tac. Ann. 6.45; Dio 60.6.8).

14 They could now enjoy only the praetorian manera offered in December. Ville's catalogue of known productions shows that imperial munera (including those of the emperor's relatives) were rare under Tiberius, while they were rather frequent not only under Augustus but also during the short reign of Caligula ( Ville, G., La gladiature en Occident des origines à la mort de Domitien [Rome 1981] 99–106, 129–34)CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

15 Eight or so pages are given to long quotations and paraphrases from ancient sources.

16 For a better treatment see Herz's, P. admirable dissertation, Untersuchungen zum Testkalender der römischen Kaiserzeit nach datierten Weih- und Ehreninschriften (Mainz 1975)Google Scholar.