Introduction

Though some expatriates have repatriated since the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and this crisis will affect future expatriation (Caligiuri, De Cieri, Minbaeva, Verbecke, & Zimmermann, Reference Caligiuri, De Cieri, Minbaeva, Verbecke and Zimmermann2020), many expatriates, especially self-initiated expatriates (SIEs) who are more globally mobile, will still continue to relocate internationally for varying reasons and, as such, may become an even more valuable resource for international organisations. Thus, it is important for researchers and organisations to understand SIEs' motivations as this has important implications for their continued expatriation and organisational performance and knowledge.

Though research on the SIEs phenomenon is no longer in its infancy (Suutari, Brewster, & Dickmann, Reference Suutari, Brewster, Dickmann, Dickmann, Suutari and Wurtz2018), researchers have called for a better understanding of issues associated with SIEs' expatriation (Alshahrani & Morley, Reference Alshahrani and Morley2015; Doherty, Richardson, & Thorn, Reference Doherty, Richardson and Thorn2013; Richardson & McKenna, Reference Richardson and McKenna2014) and, particularly, their motivations (Doherty, Reference Doherty2013; Lauring, Selmer, & Jacobsen, Reference Lauring, Selmer and Jacobsen2014; Suutari, Brewster, & Dickmann, Reference Suutari, Brewster, Dickmann, Dickmann, Suutari and Wurtz2018). Further, Brewster, Suutari, and Waxin (Reference Brewster, Suutari and Waxin2021) suggested that whilst the motives of SIEs to relocate to another country have received some attention, these studies have not explained whether motivations change over time in respect to whether the motivation to become an SIE is the same as the motivation to stay an SIE.

Expatriates remain an operationally and strategically important element of staffing for international organisations' global competitiveness (Schuster, Holtbrügge, & Engelhard, Reference Schuster, Holtbrügge and Engelhard2019; Tharenou, Reference Tharenou2013). Demand for their skills, knowledge, and experience needs to be better understood (Alshahrani & Morley, Reference Alshahrani and Morley2015; Doherty, Richardson, & Thorn, Reference Doherty, Richardson and Thorn2013; Schuster, Holtbrügge, & Engelhard, Reference Schuster, Holtbrügge and Engelhard2019). With the growing prevalence of SIEs in organisations worldwide, it is vital for organisations to understand the experience of, and provide suitable management for these skilled and valuable inter-company, inter-industry mobile individuals (Alshahrani & Morley, Reference Alshahrani and Morley2015; Doherty, Reference Doherty2013; Lauring & Selmer, Reference Lauring and Selmer2013; Nolan & Morley, Reference Nolan and Morley2014) to maximise their contributions to organisations (Al Ariss & Ӧzbilgin, Reference Al Ariss and Özbilgin2010). Understanding SIEs' motivations is essential to organisations for developing appropriate human resource management (HRM) strategies and practices to manage SIEs effectively. This current research responds to calls for more research into the motivations and changing motivations of SIEs. This research extends current research by highlighting additional factors important to decisions around specific host country locations such as: pre-established networks; prior experiences; cultural interest/affinity; and chance events and love, but suggests career is valued over other factors. Utilising the lens of self-determination theory (SDT), the research provides a theoretical contribution in highlighting SIEs' intrinsic and extrinsic motivations to relocate internationally and how these motivations may change while living and working overseas. The research question addressed is: Why are Australian SIEs motivated to expatriate to South Korea or the United Kingdom?

SIEs defined

Unlike assigned expatriates (AEs), who are posted by (and bound to) their employer to work internationally, SIEs individually and voluntarily choose to expatriate. SIEs may find employment of their own initiative on arrival in the foreign country or, to a lesser extent, prior to expatriating (Cerdin & Selmer, Reference Cerdin and Selmer2014; Suutari & Brewster, Reference Suutari and Brewster2000). Given their independent and proactive mobility across organisational, geographical, and occupational domains, SIEs have been described as pursuing boundaryless careers (Alshahrani & Morley, Reference Alshahrani and Morley2015). While some research has identified similarities between AEs and SIEs, it has also been revealed there are distinct differences including: the source of initiative (self-initiated versus organisationally-assigned); goals for the foreign job (personal goals versus organisational goals); the source of funding for employment (self-funded versus organisationally funded); and career type (Inkson, Arthur, Pringle, & Barry, Reference Inkson, Arthur, Pringle and Barry1997; Suutari & Brewster, Reference Suutari and Brewster2000). Within the expatriation/global mobility literature, there has been some focus on the distinction between SIEs and migrants. For instance, Cerdin and Selmer (Reference Cerdin and Selmer2014) differentiated SIEs from other forms of expatriation and migration in four respects; self-initiated international relocation; regular employment intentions; intentions of a temporary stay; and skilled/professional qualifications. Other researchers separate migrants from expatriates but note expatriates might have migrant status (McNulty & Brewster, Reference McNulty and Brewster2017). Migrants can be considered as individuals that have chosen to relocate without a fixed date for or intent to return to their home country/current country of residence and indeed some SIEs may subsequently apply to migrate following expatriating. Przytuła (Reference Przytuła2016) referred to migration as a relatively permanent change of residence whereas SIEs are a separate group that initiate an unlimited length of stay (without permanent intent). McNulty and Brewster (Reference McNulty and Brewster2017) suggested there are issues of construct clarity around what is a (business) expatriate and establish some boundary conditions for business expatriates. McNulty and Brewster (Reference McNulty and Brewster2017) noted that expatriates were a term initially used to refer to people that made a life elsewhere without any real possibility of return (which is what we now call migrants). McNulty and Brewster (Reference McNulty and Brewster2017) considered SIEs to meet the boundary condition of an expatriate (not a migrant) in respect to organisational employment, temporal nature of relocation, and not being citizens of the host country. Moreover, Baruch, Dickmann, Altman, and Bournois (Reference Baruch, Dickmann, Altman and Bournois2013) suggested a distinction between migration and expatriation is a legal definition of rights to permanent residency. In sum, given SIEs intend to relocate to work for a temporary period, and then repatriate or expatriate elsewhere, they are not migrants (Cerdin & Selmer, Reference Cerdin and Selmer2014; Richardson & Zikic, Reference Richardson and Zikic2007). Within this paper, the focus is on SIEs and not on migrants.

SIEs' motivations and contributions to international organisations

Research has explored the motivations of expatriates including reference to extrinsic and intrinsic motivations which may differ between business expatriates and those in religious/humanitarian organisations (Oberholster, Clarke, Bendixen, & Dastoor, Reference Oberholster, Clarke, Bendixen and Dastoor2013). Findings about the motivations of SIEs, specifically, has been diverse with earlier seminal research suggesting they are motivated by unspecified desires to seek adventure, novel experiences, and travel (Inkson et al., Reference Inkson, Arthur, Pringle and Barry1997) with later studies highlighting family, financial and career-related considerations (Lauring, Selmer, & Jacobsen, Reference Lauring, Selmer and Jacobsen2014; Muir, Wallace, & McMurray, Reference Muir, Wallace and McMurray2014; Richardson & McKenna, Reference Richardson and McKenna2006). Whilst some research found SIEs had career advancement through international experience, professional learning, and development of global networks (Nolan & Morley, Reference Nolan and Morley2014; Richardson and McKenna, Reference Richardson and McKenna2014), SIEs have been regarded as primarily motivated by personal and lifestyle rather than career goals (Doherty & Dickmann, Reference Doherty, Dickmann, Andresen, Al Ariss, Walther and Wolff2012; Doherty, Dickmann, & Mills, Reference Doherty, Dickmann and Mills2011).

SIEs represent an important resource of expertise and knowledge for many global organisations. SIEs have been deemed strategically important as they may be knowledge brokers in organisations and thus provide organisational competitive advantage (Shao & Al Ariss, Reference Shao and Al Ariss2020). Moreover, it has been suggested foreign executives with significant host country involvement (which may include having a local spouse) provide advantages to local organisations (Arp, Reference Arp2013). Increasingly employed to address skilled international manager shortages (Doherty, Dickmann, & Mills, Reference Doherty, Dickmann and Mills2011; Tharenou, Reference Tharenou2013), SIEs may constitute a much bigger and potentially more influential share of the international workforce than AEs (Doherty, Dickmann, & Mills, Reference Doherty, Dickmann and Mills2011). SIEs have: strong motivation to live abroad (Suutari & Brewster, Reference Suutari and Brewster2000); confidence to work and live abroad (Doherty, Dickmann, & Mills, Reference Doherty, Dickmann and Mills2011); greater desire for a cross-cultural experience than AEs (Doherty, Dickmann, & Mills, Reference Doherty, Dickmann and Mills2011; Suutari & Brewster, Reference Suutari and Brewster2000); and work abroad for longer than AEs (Cerdin & Le Pargneux, Reference Cerdin and Le Pargneux2010; Doherty, Dickmann, & Mills, Reference Doherty, Dickmann and Mills2011; Jokinen, Brewster, & Suutari, Reference Jokinen, Brewster and Suutari2008). SIEs may not experience the same degree of expatriate home sickness (see Hack-Polay and Mahmoud, Reference Hack-Polay and Mahmoud2020) as AEs because they have a greater cultural affinity for their host country with better cross-cultural skills and stronger social networks with locals (Tharenou, Reference Tharenou2013). Further, SIEs are known to be readily accessible to employers in the host country and inexpensive because they do not receive expatriate compensation packages (Tharenou & Harvey, Reference Tharenou and Harvey2006).

Context of the research

This research examines Australian SIEs who have relocated to South Korea (SK) or the United Kingdom (UK). The research provides insight into an under-explored area of the expatriate population (Australian expatriates) who work in globally important markets. The experiences of North American and European expatriates in Japan and China have dominated the attention of academic research (McDonnell, Stanton, & Burgess, Reference McDonnell, Stanton and Burgess2011) but less is known about Australian SIEs. South Korea and the UK are the focus of this study because they are economically important internationally and to Australia (Austrade, 2020; Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), 2007).

Though the COVID-19 pandemic has significantly reduced expatriation out of Australia, prior to the pandemic it had been estimated that there were approximately one million Australian expatriates residing abroad with many in OECD countries and the UK being a key destination (Department of Foreign Affairs & Trade (DFAT), 2016; Guest, Reference Guest2021). In addition to both South Korea and the UK being economically important to Australia, they were selected to study two very culturally distinct countries to understand if this affected Australian SIEs' motivations. Though Australia and the UK are considered culturally similar on Hofstede's dimensions of power distance, collectivism/individualism, masculinity/femininity, uncertainty avoidance, and indulgence, both Australia and the UK are quite distinct from South Korea (see Hofstede, Reference Hofstede2021). South Korea is an important host context for business and expatriates (Austrade, 2016). Over the last three decades, Australia and South Korea have maintained a growing bi-lateral commercial relationship. On 12th June 2021, Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison and South Korean President Moon Jae-in met and agreed to work towards elevating the bilateral relationship to a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership, and in progressing this agreement, the countries are building cooperation in the Indo-Pacific region (Department of Foreign Affairs & Trade (DFAT), 2021a, 2021b). The UK has traditional and long-standing economic, legal, political, and monarchical ties to Australia (DFAT, 2015). Australia's relationship with the UK is underpinned by a shared heritage, common values, and closely aligned strategic outlook and interests. This relationship is further strengthened by a shared history of active service in conflict zones and international security. Australia and the UK have maintained a growing bi-lateral commercial relationship. The UK is one of Australia's most like-minded trade partners. The UK Government's post-Brexit vision of a ‘Global Britain’ campaign includes looking to old friends to increase trade and investment with Australia viewed as a key trading partner (Department of Foreign Affairs & Trade (DFAT), 2021a, 2021b).

Although there has been some research about Australian AEs (see, Fee, Heizmann, & Gray, Reference Fee, Heizmann and Gray2017; Hutchings, Reference Hutchings2005) there is limited knowledge about Australian SIEs. It has been suggested SIE research should give attention to new contexts (Biemann & Andresen, Reference Biemann and Andresen2010; Muir, Wallace, & McMurray, Reference Muir, Wallace and McMurray2014) and McDonnell, Stanton, and Burgess (Reference McDonnell, Stanton and Burgess2011) advocated Australia as one such context. Though this study focuses on an underexplored cohort of SIEs and underexplored context, the research provides insights for SIEs generally who relocate to culturally similar and dissimilar contexts.

Literature review

SIEs – as distinguished from assigned expatriates (AEs)

While AEs might have some say about which country or region they prefer for international relocation, they are typically assigned on a fixed-term basis to meet a specific job or goal in an organisation's international operations and then return to the same organisation in the home country. The international experience is intended to result in career development for the individual, competent completion of the job assignment, and organisational learning with the transfer of new skills and knowledge after repatriation (Tharenou, Reference Tharenou2013). In contrast, SIEs voluntarily relocate internationally, usually for an indefinite or non-fixed time (Suutari & Brewster, Reference Suutari and Brewster2000). Early literature suggested people that voluntarily moved to work overseas often had diffuse and unspecified individual goals such as to ‘see the world’, ‘try something different’, or to ‘find myself’ (Inkson et al., Reference Inkson, Arthur, Pringle and Barry1997). Inkson et al. (Reference Inkson, Arthur, Pringle and Barry1997) undertook initial research on self-initiated overseas experience (or what are now referred to as SIEs) and suggested they are differentiated from AEs based on the career type they pursue. Inkson et al., (Reference Inkson, Arthur, Pringle and Barry1997) argued that AEs pursue the ‘microcosmic international representation of the ‘organisational career’ in which the individual moves from role to role building company-relevant skills and ascending in status within one company’ (p. 352). In comparison, those who pursued self-initiated expatriation are the microcosmic representation of an individually-driven career in moving between organisational and national boundaries, aimed at the development of skills across the global labour market (Inkson et al., Reference Inkson, Arthur, Pringle and Barry1997). Subsequent research has noted that SIEs pursue increasingly self-managed and fluid careers characterised by the engagement of temporary assignments centred on building skills and competencies (Alshahrani & Morley, Reference Alshahrani and Morley2015; Biemann & Andresen, Reference Biemann and Andresen2010).

Self-initiated expatriates (SIEs) as boundaryless careerists

SIEs have been categorised as boundaryless careerists (Alshahrani & Morley, Reference Alshahrani and Morley2015; Biemann & Andresen, Reference Biemann and Andresen2010; Jokinen, Brewster, & Suutari, Reference Jokinen, Brewster and Suutari2008; Suutari & Brewster, Reference Suutari and Brewster2000), reflecting SIEs' independent and proactive mobility across organisational, geographic, and occupational domains. Distinct from traditional careers where an individual may progress the hierarchy of a single organisation, the boundaryless career concept (Arthur & Rousseau, Reference Arthur and Rousseau1996) refers to careers as individually planned, designed, and evaluated across multiple organisations, occupations, industries, and national boundaries. SIEs have been described as the most extreme form of a boundaryless career (Thorn, Reference Thorn2009). While AEs receive long-term career planning within the organisation, SIEs design their own career goals (Cerdin & Le Pargneux, Reference Cerdin and Le Pargneux2010). Biemann and Andresen (Reference Biemann and Andresen2010) and Alshahrani and Morley (Reference Alshahrani and Morley2015) found SIEs exhibit higher organisational mobility and more frequently intend to change organisations than AEs. Moreover, Linder (Reference Linder2018) found SIEs tend to be less embedded in organisations than AEs, and as career satisfaction is a result of deep embeddedness, AEs were more likely to perform tasks exceeding contractual requirements. Increased evidence of boundaryless career orientations among expatriates underlines the growing importance of internal career characteristics for their career decisions (Wechtler, Koveshnikov, & Dejoux, Reference Wechtler, Koveshnikov and Dejoux2017) but there has been limited examination of SIEs' career decisions. Given that Gratton (cited in McKeown & Leighton, Reference McKeown and Leighton2016) suggested an ageing world population will have multiple stages of life and a much wider array of ways of working into older ages, self-initiated expatriation is likely to form part of working in different life stages.

Motivation to expatriate

The literature has argued that the motives of SIEs are more complex than originally proposed (Muir, Wallace, & McMurray, Reference Muir, Wallace and McMurray2014; Nolan & Morley, Reference Nolan and Morley2014; Richardson & McKenna, Reference Richardson and McKenna2006; Selmer & Lauring, Reference Selmer and Lauring2011). Suutari, Brewster, and Dickmann (Reference Suutari, Brewster, Dickmann, Dickmann, Suutari and Wurtz2018) review contrasting AEs and SIEs found motivations of SIEs vary according to demographic factors and the industry or sector in which the SIEs work, although non-career motivations are consistently of more significance for SIEs than AEs. Early research described those who voluntarily relocated to work overseas as being on a personal odyssey and as a youthful ‘backpacker culture’, who travelled overseas for a prolonged period of travel, work, and tourism. Typically, these groups comprised young graduates who viewed overseas experience as a ‘rite of passage’ (Inkson et al., Reference Inkson, Arthur, Pringle and Barry1997). Later research by Richardson and Mallon (Reference Richardson and Mallon2005) and Doherty, Dickmann, and Mills (Reference Doherty, Dickmann and Mills2011) found, irrespective of demographic influences (such as age, gender and accompanying or non-accompanying children), the desire for adventure, challenge and opportunities offered by travel and work and personal and lifestyle goals rated consistently as the most influential decision for SIEs to move abroad.

Richardson and McKenna (Reference Richardson and McKenna2006) revealed a more complex picture of the motivations of SIEs, encompassing five broad categories: adventure/travel, a life change/escape; what is best for the family; financial reasons; and using the experience for career-building purposes. Jackson et al., (Reference Jackson, Carr, Edwards, Thorn, Allfree, Hooks and Inkson2005) found motivations may vary from one geographical location to another suggesting the importance of a particular host location. The motivation for life change/escape was a significant motivating factor in studies of older and younger people (Richardson & McKenna, Reference Richardson and McKenna2006; Wechtler, Reference Wechtler2018). The desire to create a life change involves physical distance from negative work or life situations and expatriation is an avenue for escaping boredom with the home country as well as an opportunity for change (Selmer & Lauring, Reference Selmer and Lauring2011; Suutari & Brewster, Reference Suutari and Brewster2000). The desire to do what is best for the family may also play a significant role in the decision to move abroad (Doherty, Dickmann, & Mills, Reference Doherty, Dickmann and Mills2011; Richardson & Mallon, Reference Richardson and Mallon2005; Richardson & McKenna, Reference Richardson and McKenna2006; Selmer & Lauring, Reference Selmer and Lauring2011). Selmer and Lauring (Reference Selmer and Lauring2011) found unmarried SIEs were mostly motivated to expatriate to change their life, but Tharenou (Reference Tharenou2013) found being married and having a family created barriers to expatriation. Thorn (Reference Thorn2009) found, after travel, being in a relationship with a person from the host country was the second most important motivation to expatriate. Further, impulsiveness, fate, chance, or luck also present opportunities for SIEs (Muir, Wallace, & McMurray, Reference Muir, Wallace and McMurray2014; Richardson & Mallon, Reference Richardson and Mallon2005).

Doherty, Dickmann, and Mills (Reference Doherty, Dickmann and Mills2011) explained that, compared to AEs, career aspirations are complementary to SIEs' personal life paths and their international experience is motivated by the achievement of personal goals with future career prospects less important. Yet, whilst some women SIEs were motivated by personal reasons, they serendipitously also acquired career capital Myers, Inkson, and Pringle (Reference Myers, Inkson and Pringle2017). Some research suggested developing a career alongside other personal development considerations was important (Nolan & Morley, Reference Nolan and Morley2014; Richardson & McKenna, Reference Richardson and McKenna2006, Reference Richardson and McKenna2014). Biemann and Andresen (Reference Biemann and Andresen2010) found SIEs perceive their foreign work experience as a valuable competitive asset on the external labour market and accumulation of career capital provides accelerated development opportunities. In contrast, Pinto, Cabral-Cardoso, and Werther (Reference Pinto, Cabral-Cardoso and Werther2020) found young and highly-educated individuals reported professional achievements lower than they had expected.

SIEs may be motivated by financial incentives to earn and save a large amount of money (Lauring, Selmer, & Jacobsen, Reference Lauring, Selmer and Jacobsen2014; Selmer & Lauring, Reference Selmer and Lauring2011; Suutari & Brewster, Reference Suutari and Brewster2000). Thorn (Reference Thorn2009) and Selmer and Lauring (Reference Selmer and Lauring2012) studies, found, however, that financial incentives scored lower than other motivating factors. Richardson and Mallon (Reference Richardson and Mallon2005) and Selmer and Lauring (Reference Selmer and Lauring2011) found marriage and/or having children was influential when financial incentives were the main reason for expatriation.

Muir, Wallace, and McMurray (Reference Muir, Wallace and McMurray2014) noted that, given SIEs can self-select their host destination, they may choose a host country with a personal appeal. Napier and Taylor (Reference Napier and Taylor2002) found SIEs who had studied in a specific country earlier in their life (e.g., as a school or university exchange student) often returned later to improve their language skills or explore the culture further. Other SIEs expatriated to a specific country to re-establish contacts with friends or family or for personal attachment and interest such as family background (Muir, Wallace, & McMurray, Reference Muir, Wallace and McMurray2014). Doherty, Dickmann, and Mills (Reference Doherty, Dickmann and Mills2011) noted country-level initiatives, regulations and societal patterns, and attractiveness of employment opportunities also influence an SIE's decision to live in a specific location. SIEs also have greater interest in traveling to developed countries because of security concerns, healthcare systems, political stability, and desire for a better lifestyle (Al Ariss & Özbilgin, Reference Al Ariss and Özbilgin2010; Doherty, Richardson, & Thorn, Reference Doherty, Richardson and Thorn2013). Some SIEs purposefully avoid moving to a location perceived as culturally challenging (Doherty, Richardson, & Thorn, Reference Doherty, Richardson and Thorn2013).

Self-determination theory (SDT)

Noting that people vary in levels and orientation of motivation, Deci and Ryan (Reference Deci and Ryan1985) coined the concept of SDT in which they argue that motivation can be distinguished based on different reasons or goals which then lead to actions. SDT was used to distinguish between behaviour that is volitional (entailing freedom and autonomy and a sense of self) and behaviour that is accompanied by pressure and control and not representative of an individual's self (Ryan & Deci, Reference Ryan and Deci2000). Ryan and Deci drew a distinction between intrinsic motivation and extrinsic motivation with intrinsic motivation referring to when someone does something because it is inherently of interest or enjoyment whilst extrinsic refers to someone doing something because it leads to a separable outcome. Intrinsic motivation involves free choice without an expectation of reward or approval (Ryan & Deci, Reference Ryan and Deci2000). Contrasting with earlier views that extrinsic motivation cannot be autonomous, Deci and Ryan (Reference Deci and Ryan1985) referred to extrinsic motivation as the ability to self-regulate such activities without external pressure. This is described within SDT as the internalisation and integration of values and behavioural regulations (Deci & Ryan, Reference Deci and Ryan1985).

Deci and Ryan (Reference Deci and Ryan1985) presented motivations on a continuum in which internalisation is a process taking in regulation and integration is a process through which people transform regulation so that it emanates from a sense of self. They characterise various types of motivation as reflecting differing degrees of autonomy or self-determination The continuum has six points including (a) amotivation – lacking an intention to act, (b) external regulation – the least autonomous form of extrinsic motivation in which behaviour occurs in response to external demand or reward, (c) introjected regulation – a type of internal regulation in which people perform actions to avoid guilt or attain ego enhancements or pride, (d) regulation through identification – more autonomous/self-determined in which people's behaviour reflects regulation as their own, (e) integrated regulation – the most autonomous form of extrinsic motivation in which regulation is fully assimilated to self, and, (f) intrinsic motivation – the prototype of self-determined activity.

Though originally applied to educational settings by Ryan and Deci (Reference Ryan and Deci2000), SDT has been expanded to work and organisations and other life areas and is utilised by researchers across many disciplines especially organisational behaviour, management, leadership, and HRM. It is important to understand the various types of motivation especially given that, in contrast to introjected and extrinsic motivation (controlled regulation), intrinsic and identified motivation (autonomous regulation) result in positive individual and organisational outcomes (Manganelli, Thibault-Landry, Forest, & Carpentier, Reference Manganelli, Thibault-Landry, Forest and Carpentier2018). Thus, SDT can guide the development of policies, practices, and organisational environments that promote both wellness and high performance (Deci, Olafsen, & Ryan, Reference Deci, Olafsen and Ryan2017).

SDT – application to expatriates

A range of researchers have examined AEs and SIEs through the lens of SDT. Zhao, Liu, and Zhou (Reference Zhao, Liu and Zhou2016) utilised SDT to demonstrate that a boundaryless mindset has a positive influence on expatriate task and contextual performance (mediated by proactive resource acquisition tactics) and further noted that cultural intelligence enhanced proactive resource acquisition tactics. Schreuders-van den Bergh and Du Plessis (Reference Schreuders-van den Bergh and Du Plessis2016) referred to autonomy and choice as motivators in the adjustment process of female SIEs and highlighted this group had opportunities for reinvention as examined in SDT. Chen and Shaffer (Reference Chen and Shaffer2017) utilised SDT to explain how multi-dimensional forms of perceived organisational support influence SIEs' organisational and community embeddedness and highlighted that as SIEs have been assumed to receive little organisational support, it is important to understand the role of support resources for SIE embeddedness. Singh, Vrontis, and Christofi (Reference Singh, Vrontis and Christofi2021) examined SDT in relation to how SIEs' mindfulness influences their resilience and consequent improvisation in the workplace. Shaffer, Kraimer, Chen, and Bolino (Reference Shaffer, Kraimer, Chen and Bolino2012) highlighted that both AEs and SIEs have a range of external and internal influences on choosing global work and extrinsic and intrinsic motivations.

Oberholster et al., (Reference Oberholster, Clarke, Bendixen and Dastoor2013) suggested the need to extend the SDT model of extrinsic and intrinsic motivations to expatriates. They examined expatriates in religious and humanitarian organisations and added altruism to expatriate motivators, and they also suggested that SDT-framed expatriate research provides a richer understanding of the motivations of workers to undertake expatriation. This current research extends the extant research that has examined SDT in relation to expatriates and SIEs, specifically, in demonstrating, through the lens of SDT, initial motivations as well as changing motivations during self-initiated expatriation.

Methods

The research involved a qualitative study of Australian SIEs living and working in South Korea or the UK. Rich, detailed accounts of individual and subjective experiences were gathered through semi-structured interviews providing flexibility to balance researcher questions and issues of interest to the interviewee (see Tashakkori & Teddlie, Reference Tashakkori and Teddlie2010). The interviews included questions about: individuals' demographic data and their employing organisation; motivation to expatriate; intended length of stay in the host country; reasons to choose the host country and to stay or to leave, and any other points interviewees considered relevant to their motivations.

Procedure and access

Using a purposive sampling criterion, SIEs were selected who matched Inkson et al. (Reference Inkson, Arthur, Pringle and Barry1997) definition of independently relocating abroad to work for a temporary period. SIEs self-identified as Australian through citizenship, permanent residency status, generations of family residing in Australia, or being born or raised in Australia. Moreover, the recruitment materials referred to seeking research participants who had independently moved to South Korea or the UK to work (not transferred overseas by an employer). Thus, the interviews self-identified as SIEs. Prior to commencing an interview with a potential participant, clarification was sought that the individual fitted the criteria of SIE (as the researchers defined it based on prior research).

Participants were recruited via various organisations associated with expatriates including the alumni lists of selected Australian universities, the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, the Australian Embassy, the Australian Chamber of Commerce, the Australian and New Zealand Association, and Australian expatriate sporting and social clubs in each location. The first author had previously spent time living and working in South Korea, and this provided knowledge of organisations (such as chambers of commerce) who would be suitable for distributing, to their database of members, requests to participate in the research. These organisations invited members (on their databases) to participate in the research by providing the project information and researchers' contact details through emails and newsletters. Potential interviewees were also contacted (and invited to participate) through social media (LinkedIn, Twitter, and Facebook). SIEs were also recruited via advertisements placed in expatriate magazines and websites. A snowball sampling strategy was also used with referrals of professional and social acquaintances of research participants (see Biernacki & Waldorf, Reference Biernacki and Waldorf1981). The pool of potential interviewees was limited to those with access to email and who self-selected to be interviewed.

Sample

Over 13 months, 58 participants were interviewed until data saturation was reached. Of the total participants, 26 had lived and worked in South Korea, 29 in the UK, and the remaining three had initiated expatriation to both South Korea and the UK (and were asked to respond to questions about their time in each location). Therefore 58 SIEs were interviewed but the sample captured 61 SIE experiences, which well exceeds Saunders and Townsend (Reference Saunders and Townsend2016) criterion for sample size for qualitative, interview-based studies. Interviews were conducted in English although several participants also mentioned South Korean culture-specific terms (which they were asked to translate to ensure accurate understanding). All interviews were audio recorded. Interviews conducted in person or by Skype ranged from 40 to 132 min.

Australian SIEs in both South Korea and the UK were generally single upon arrival and had lived in the host country for less than two years. SIEs in the UK were more commonly female and SIEs in South Korea mostly worked in education and government. Women are underrepresented amongst expatriates (Haak-Saheem, Hutchings, & Brewster, Reference Haak-Saheem, Hutchings and Brewster2021). It was interesting that those who self-selected to participate in this research include equal numbers of people who identified as men or women, but this likely reflects women being better represented amongst SIEs compared to company-assigned expatriates (Tharenou, Reference Tharenou2010). Yet, the gender split differed according to the country of relocation. Most of the women in the sample were in the UK whilst most of the men were working in South Korea. The participants self-selected to participate in the research. The sampling was not deliberately done based on gender, but the differences do reflect some general trends. Though the UK is consistently ranked the first or second top destination for Australian expatriates, there are gender differences in choices of location. A recent article found popular destinations for Australian expatriates overall were UK, USA, Singapore, Thailand, and Indonesia (ExpatInfoDesk, 2020). Yet, in a study of top destinations for expatriate women the countries included more western countries i.e., USA, UK, Canada, France, and UAE with 16.47% of Australian women expatriates relocating to the UK (Evans, Reference Evans2019). Thus, most women in the sample being in the UK reflects preferences highlighted in earlier reports. In 2019 there were approximately 727,000 male and 545, 000 female foreigners in South Korea (Yoon, Reference Yoon2021), so though the sample does not include the same percentage of males/females, it does reflect the trend towards a predominance of male expatriates in South Korea.

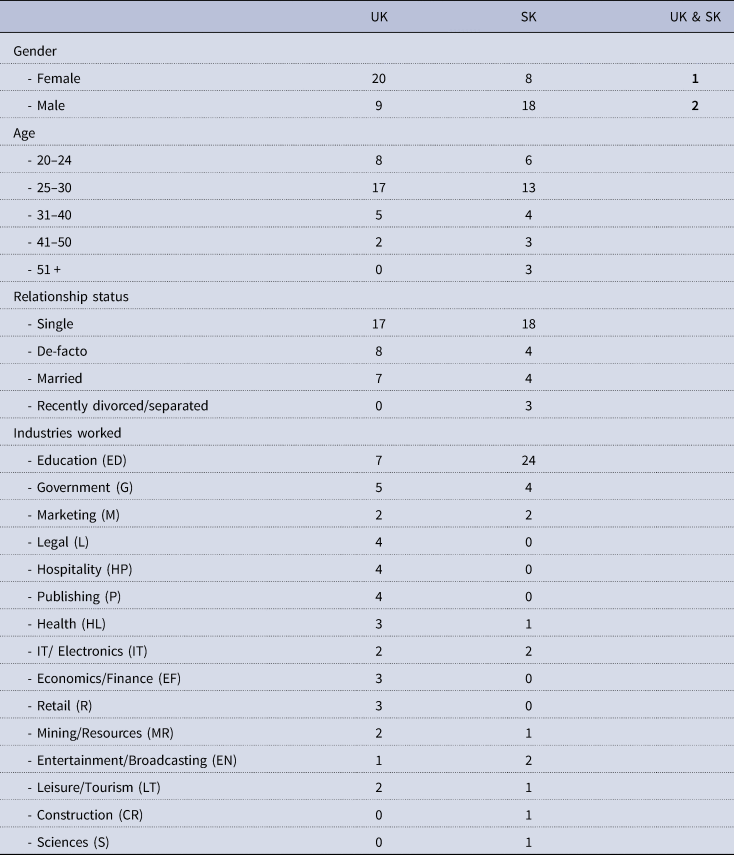

A summary of the demographic data of the interviewees is presented in Table 1 and Figure 1. To ensure anonymity code identifiers are used. For instance, the code 4-UK-M-LT/R/HP refers to interviewee 4, located in the UK, male, and working across leisure/tourism, retail, and hospitality.

Fig. 1. Length of stay in host location. N.B. Total includes three interviewees who had worked in both South Korea and UK.

Table 1. Demographic data of participants

Analysis

Each interview was recorded and transcribed verbatim, and subsequently imported into the NVivo software tool which was utilised to facilitate the coding, analysis, and mining of comments from the qualitative data. The process of interviewing and transcription assisted in the generation of a draft range of key themes into which data could be coded into NVivo. The interviewee responses were contextualised and grouped (where possible) and from this, several recurring themes and patterns became the ‘parent nodes’ and lesser order ‘child nodes’. Throughout the on-going process of coding the remaining interview transcripts, several other key themes emerged which resulted in additions and refinements being made to the original set of nodes. To ensure consistency in the coding of all interview transcripts, interviews that had been coded earlier were then revisited and revisions were made. Utilising NVivo to code the interviews into key themes and patterns allowed for ease of access to indicative and divergent quotes as well as the formation of tables comprising frequency counts of commonly occurring themes. This process added richness and depth of knowledge and proved valuable for analysing the lived experiences of individuals. It also enabled a numerical representation of the frequency of occurrence, which aided in highlighting common significant issues identified across the interviewees.

Outside of the coding that had taken place using NVivo, the manual development of tables and charts provided a further level of analysis which assisted in ensuring the accuracy of reported data, decreasing bias, and increasing the reliability of the research. Thematic analysis was selected as appropriate for this study, because it allows for a rich, detailed, and complex account of the intricacies and meaning within a data set data-labelling and identification and patterning of recurring themes (Miles & Huberman, Reference Miles and Huberman1994).

Findings

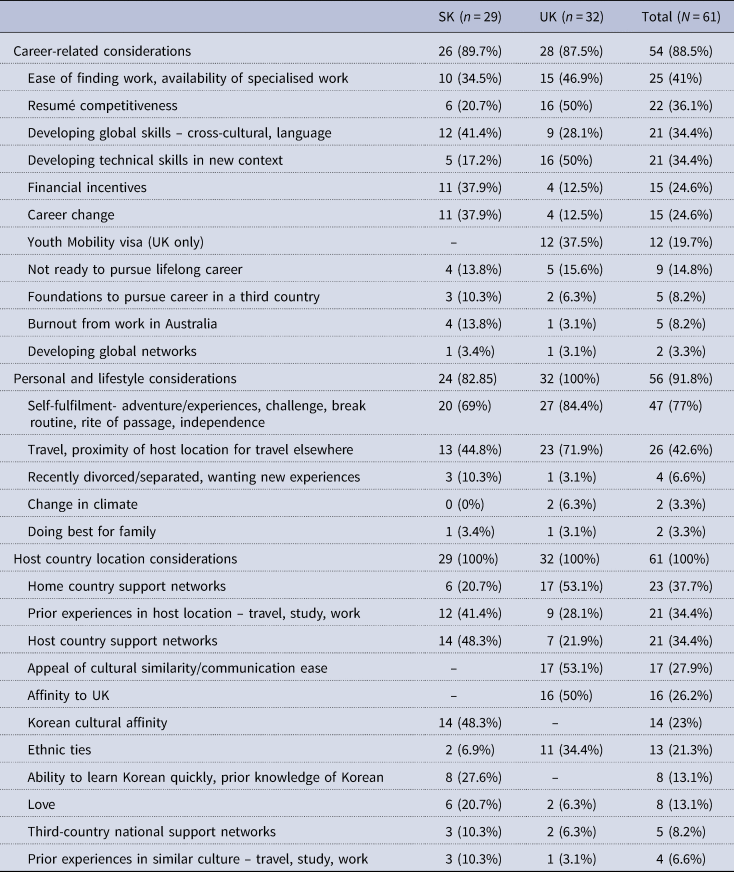

The findings provide insight into the complex and multifaceted factors motivating Australian SIEs to relocate abroad. Table 2 shows the three factors that were initial motivators for relocating: career-related considerations; personal and lifestyle considerations; and specific host country considerations. While the numbers/percentages may suggest almost equal mention of career and personal/lifestyle considerations, throughout the interviews participants spoke in much more detail (focus and range) and more frequently about the importance they placed on career-related considerations as an initial motivation to relocate. SIEs placed great emphasis on their expatriation as being a career-enhancing experience to develop work-related and personal skills and portable, tradeable career capital.

Table 2. Initial motivating factors for self-initiated expatriation

First, SIEs commonly said they were most motivated by career-related factors and exhibited strong career orientation marked by personal investment in their work and desire for upward mobility within their occupation. Yet, when they perceived themselves to be underutilised or under supported, they exhibited transient behaviours and proactively shaped their careers across multiple organisations, occupations, industries, and national boundaries. The findings show some deliberately pursued boundaryless mobility whereas others found or accepted other positions to continue expatriation. Second, personal and lifestyle considerations also affected choice to self-initiate expatriation (although it was either secondary, or ran parallel, to career considerations). Third, while SIEs may have sought to expatriate out of a general yearning for an international experience, they also expatriated to a specific country because of the appeal of various host country characteristics. Fourth, the findings identified SIEs' motivations evolve in that, although they may be motivated by an initial set of factors, upon arrival (or shortly thereafter), a separate set of factors determined their desire to stay within or leave the host country.

Career-related considerations

SIEs discussed a variety of extrinsically motivated career-related considerations influential in their decisions to relocate abroad. The career-related issues they mentioned (shown in Table 3) were grouped into four key themes: ease of finding work; career-development opportunities; financial incentives; and career change.

Table 3. Career-related considerations

The most frequently emphasised career-related factor motivating expatriation was the challenges SIEs found in securing gainful employment within Australia and the relative ease of finding work overseas. As protean careerists, some SIEs, confronted with unappealing or insufficient opportunities within the Australian labour market sought more attractive job opportunities in South Korea or the UK. SIEs revealed the host country's economic climate and reputation as an attractive employment opportunity played a significant role in their decision to expatriate. Indicative of interviewees' views, a participant commented there were ‘aspects of my profession that weren't available in Australia to the same extent’ (1-UK-F-EF) and another elaborated: ‘… there's far more opportunities in the UK. There's a greater mass of work available and it is at a greater scale in areas that simply aren't open or available in Australia’ (5-UK-M-MR).

Another common factor motivating expatriation was the anticipation of opportunities for positive future career development. SIEs were driven primarily by a desire to make their resumé more competitive and to acquire global (cross-cultural, language) skills and technical skills. Also mentioned was developing career-related global networks and using the experience as a foundation for a career in another country. SIEs often described perceiving their international work experience as a valuable step towards longer-term career goals. One participant highlighted:

‘It demonstrates that you can relocate your life and start afresh and that you have flexibility and an ability to adapt to changing circumstances … having that experience on my CV when I return to Australia will make some steep changes in my career, which were proving difficult to make while I was in Australia’ (1-UK-F-EF).

However, while most participants spoke of the career-enhancing effect of working abroad, several participants suggested the international experience may not have been conducive to improving their employability and they had taken a ‘backwards step’ by placing their careers on hold in Australia. In contrast, others feel that although the expatriation was not immediately beneficial to their career in the host country, they perceived the experience of working abroad as adding to their future employability upon repatriation to Australia, and thus, it was still valuable in the context of a boundaryless career. One participant noted it was ‘worthwhile and rewarding in the long run’ (19-UK-F-HL).

SIEs also indicated the prospect of greater financial rewards and benefits (than in Australia) was an important motivating factor and included making and saving a large amount of money and the comparative affordability of life in the host country. Financial incentives were of relevance primarily to individuals who were in later career stages and who had relocated from Australia to better their financial position and their employment situation. As one participant explained:

‘We own our house here. We don't have any debts. We make a very good living. Whereas if I was in Australia, I could well still be working in someone's office getting taxed at 48%’ 13-SK-M-ED.

Other career-related considerations included the desire for career change arising from: the boredom of their work routine in Australia; not being ready to pursue a lifelong career; the opportunity to discover future career plans; or to escape burnout from the pressures of their existing work. One participant stated:

‘I was getting bored of my job and couldn't really think of the next step in my career. So, I kind of wanted to get a meaningful job in my [industry] – something that would assist me in the future’ (14-SKandUK-M-ED).

Personal and lifestyle considerations

The personal and lifestyle factors mentioned by participants were categorised across four major themes: self-fulfilment; travel; family reasons; and desire for change in environment (see Table 4). Whilst most of these factors were intrinsic motivations, factors related to family were extrinsic to the individual's own situation given a focus on others and their needs.

Table 4. Personal and lifestyle considerations

The most frequently emphasised personal/lifestyle factor motivating expatriation was self-fulfilment including the desire for novel experiences/adventure, breaking away from routine, being challenged and testing themselves, independence, and rite of passage. Participants noted:

‘I really like adapting, learning new things and challenging myself. Unless I'm progressing and improving myself, I get a little bit frustrated’ (16-SK-M-M).

‘I was feeling stifled, and life was becoming repetitive and conservative. … people my age were either settling down, buying houses, and getting into a routine. I wasn't ready for that … I wanted to live in a big city where there was culture, and arts, and travel opportunities. It just seemed to be a bit more exciting and an experience that would be good to have before I got older and had responsibilities keeping me in Australia’ (2-UK-F-P/L).

Desire to travel was also influential in decisions to relocate abroad and was reflected in comments of younger and older, more experienced, SIEs. Those in the 20–24 and 25–30 age groups explained that as recent graduates or young professionals, they sought travel as a rite of passage, to challenge themselves, have new experiences and learn new skills. One participated noted:

‘I really loved the idea of the proximity of everything. We thought all of Europe was so accessible from the UK … Definitely one of the biggest benefits we saw of going there was being able to travel and visit places relatively cheap and easily’ (12-UK-M-MR).

Those in the older age groups described a longing to travel after: raising their children to adulthood; going through a recent separation; overcoming illnesses; or being at a life stage for considering dramatic career path and lifestyle changes. One participant said:

‘I had raised my two boys and my life was very structured and financially I hadn't had an opportunity to travel. Once they got older the thought of travelling and working was just brilliant. I was like ‘well this empty nester isn't going to stay here – I'm out of here’ (3-SK-F-ED).

Family reasons were another common motivation for expatriation. SIEs relocating with an accompanying spouse/partner or children were motivated by improvement of living standards and quality of life for their family (and themselves), and international schooling for children. In discussing the importance of ‘doing what is best for the family’ some SIEs noted family reasons may be a disincentive to expatriate i.e., difficulties finding suitable schooling for children, removing children from their social groups in Australia, accompanying spouse/partner not being legally entitled to work – and this needed to be considered as part of competing motivations to (or not to) relocate.

A small number of SIEs expressed a desire to withdraw or ‘escape’ or ‘recreate themselves’ after marital separation or relationship breakdown in Australia. A change in environment was also noted, although that can be challenging as one participant reflected:

‘Quite honestly I do find hot weather quite intolerable … I was really finding that the summers and the heat in Australia were becoming a little bit too much for me, and I needed a milder climate’ (5-UK-M-R-MR).

Host location considerations

While SIEs chose to expatriate out of a general desire for an international experience, they were also drawn to a specific country because of the appeal of various host country characteristics such as: pre-established networks; prior experiences; perceived (cultural) ease of adjustment, ethnic ties, cultural and historical knowledge; and chance events and love (see Table 5). Whilst most of these factors were extrinsic motivators, aspects of the host country also demonstrated intrinsic motivations, namely, chance events and love, which were pursued for personal inherent interest or enjoyment.

Table 5. Host country location considerations

The availability of pre-established support networks (comprising both locals and other expatriates) was the major motivating factor in the choice of a specific host country location. Ties to the host country through acquaintances, friends or family and the availability of information and support made relocating to the country more appealing compared to other countries without networks. As noted:

‘My friend had been living in Korea … Seeing him do something like that made me think that moving to a different country and finding your way around was not an insurmountable task … I was also lucky because my friend helped me find work’ (14-SKandUK-M-ED).

Prior experience in the host country was an important consideration in the decision to return. Participants who had spent time in the host country previously for travel, work, study, internships, or traineeships sought to either stay or return to the country to improve their language skills, maintain networks, or further engage with the culture of interest. One participant reflected:

‘Coming here previously made me fall in love with Korea and that's when I thought I've got to come back here to work … Seeing such a vibrant, high technology city and the Koreans just going about their day just opened my eyes so enormously. I just couldn't get the smile off my face’ (2- SK-M-ED).

Prior exposure to a country's culture via media, friends, family, and ethnic ties and/or shared histories was also an influencing factor. SIEs living in the UK who had ethnic or cultural ties described feelings of ‘connection’, ‘familiarity’ and ‘coming home’. SIEs without such links to the UK remarked upon a sense of cultural familiarity given shared association with the Commonwealth, historical and long-standing monarchic ties, and the common English language. One participant commented:

‘It's a safety net to move to somewhere where you know it's not going to be too culturally dissimilar, or daunting … there's a feeling of familiarity, even though its thousands of kilometres away … we've had access from a young age to what the stereotypical English way of life is' (2-UK-F-P/L).

Some participants who relocated to South Korea explained they purposefully wanted to live in a culturally different environment. One participant noted:

‘I chose Korea because I wanted to jump into a place where I had no background and would find it very difficult to acclimatise. I wanted to challenge myself, and I thought that moving to a place where I don't speak the language and don't understand the culture would be one of the most difficult things I could imagine’ (10-SK-M-ED).

SIEs also referred to love (which is not defined in this research but was as an encompassing term used by participants) as a motivating factor. Several men and women SIEs referred to the pursuit of love through relocating abroad to pursue or continue a relationship with a host country national or to accompany their SIE partners. Due to visa constraints in Australia, relocation to the partner's home country motivated their expatriation. As one participant explained:

‘I had wanted my Korean wife to come to Australia, but the Australian government just about wanted war and peace just as proof that it's a genuine relationship …. I lost my patience with that very quickly. So, the other option as far as being able to stay together was to go to Korea … as long as you're married to a Korean national, you can live here’ (13-SK-M-ED).

Some SIEs also perceived opportunities simply arose due to ‘fate’, ‘chance’ or ‘luck’. Such random chances to expatriate tended to occur through meetings with nationals of the host country or encounters with acquaintances or friends in Australia and were pursued by the SIEs for intrinsic interest. Indicative quotes from participants include:

‘I was working around a hundred hours a week. So, I needed a life change … I was complaining about things at work to a mate at a party and he said, ‘Hey why don't you talk to this guy over here. He's just come back from two years teaching English over in Korea’. So, I had a chat with him and then put in my resignation from work and I was over here about two months later. Yeah. So, that was it. The original reason to come here was less work, about the same pay that I was getting, change of lifestyle’ (25-SK-M-E).

‘ … So my friend's parents invited me here, and they were awesome. I learned to ski here. And then I kept wanting to ski, but money was a bit of an issue, but I could live really cheaply in Korea and ski a lot, so I came back another winter, and two more winters. And then I met a Korean girlfriend in Australia, and we were really close, and I got the chance to come to Korea as an exchange student. And then [a] Professor [name omitted] had his internship … so, he offered me that. It just kind of all fell into place. I really like Korea as a country too’ (28-SK-M-IT/LT/ED).

Another participant said that an aspect of their decision to relocate was the prospect of love associated with fate/chance. As she stated:

‘Certainly, also being 26–28 I was hoping that I might meet someone over here and I had this romantic idea that I would meet a lovely English fellow’ (11-UK-F-P/LT/ED).

Changing motivations

From the outset of their expatriation some SIEs had diverse motivations and approached their relocation holistically by aligning their career path with their personal/lifestyle desires. With the capacity to self-direct their protean and boundaryless careers, SIEs sought personal learning, development, and growth in both career and personal/lifestyle. One participant explained:

‘It was a combination of things … to experience something new, to challenge myself and meet new people … I was also interested in the culture … I knew the experience of living and working in South Korea would benefit me in the future both professionally and personally - it's not something that you would find on a resume of someone my age’ (5-SK-F-ED).

Many participants noted that although they had initially relocated for specific reasons, over time other factors affected their desire to stay in the host-country longer or leave prematurely, thus, their motivations changed during their expatriation. For one there was a change in overall life motivations, as explained:

‘I remember thinking at the time that I wasn't ready to make that career step. I need to have that overseas experience. And when I left, I did intend on coming back at the end of two years and continuing on my career path. Now that I am over here my priorities have changed and I am not so interested in resuming the career that I had in Australia … I was 26 when I came over here so I thought that now is the time to take my two years, travel and live the lifestyle and then go back home and get serious. Now I might not do that’ (11-UK-F-P/LT/ED).

Eight SIEs who had originally been motivated by intrinsic desires for adventure, travel, and personal challenge, or because they just wanted a change in their lives, realised, after arriving in the host country, the experience could develop their career and future work opportunities. Thus, the extrinsic motivators encouraged them to remain in the host-location longer than originally intended. These changing motivations are demonstrated by reflection from several participants, as follows:

‘The main reason for me going was to travel. Travel came first, career came second. After the first year, that completely changed. Career came first, and travel came second … I thought ‘right, you've got a real opportunity here. You can sit back and just cruise on by in your job or you can really make a go of it and do great things’. So, I decided to focus on that. The industry I worked in was competitive, people were very driven, and people progressed quickly, so that helped motivate me. It also helped the travel fund. I was earning more money so I could travel to a lot more places' (18-UK-F-M).

‘There weren't really any career development motivations, or financial motivations for choosing London. I didn't really care. Once I'd moved here, people said to me that it was a great opportunity, it's a great place to get a job and to learn, and that sort of thing. And then when I researched it more, I realised that they were right … there were so many more opportunities in London than there would be in [Australia]’ (6-UK-F-M).

‘Career development wasn't originally a consideration at all. Things like travel and desire for new experiences took precedence … after some time I realised I should be working full-time and so I worked in administration management and up to project management’ (26-UK-F-ED).

‘My motivation would definitely have been wanting a change … I knew that I didn't want to settle down until I had this experience … Growing my career wasn't an initial motivator, however when I arrived here I thought, hey this is what I'm going to do. I'm going to try to get back into HR and earn a lot of money to send back home … have a nest egg so I can just buy a house, do whatever, and just be settled. But that wasn't an initial motivation for me. It was just to get out there, see the world before I get stuck doing, you know, boring stuff … For me, working was just to fund my traveling. Progressing career-wise, that came afterwards' (21-UK-F-HL).

Although SIEs may initially be motivated by a yearning for adventure and novel experiences, such desires may lead to, or occur alongside, career-related factors. For most, personal and lifestyle aspirations either fit alongside primary career considerations or, throughout expatriation, become more prevalent. Throughout their relocation SIEs assessed their experiences against their goals and the value of networks and relationships with organisations and communities. These merits were measured against sacrifices made if they returned home or sought alternative options in other countries.

Some SIEs discussed how their intended length of stay in the host location influenced the degree they sought to establish themselves locally through work and non-work networks. Those who viewed their expatriation as short-term said their investment in relational development with locals, other expatriates and their employing organisation was low and the cost of breaking these links was relatively low. For this group, responsibilities were primarily focused on themselves or their immediate families and their overall wellbeing rather than on their employer. SIEs with short-term views generally attributed less value to the position held or employing organisation than to skills and competencies acquired and attributed their career success to their personal efforts and decisions.

Other SIEs exhibited deep personal investment in their work. SIEs who viewed their expatriation as long-term in nature highlighted high investment in relational development with locals, other expatriates and their employer and viewed the cost of breaking such links as affecting upward career mobility. Despite possessing the capability to pursue a fluid career, SIEs with long-term prospects invested considerable effort for their employer, marking their strong career orientation and upward mobility in the host country location.

Discussion

In response to the research question, Why are Australian SIEs motivated to expatriate to South Korea or the United Kingdom?, the following sections examine: predominant or simultaneous motivations; SIEs as boundaryless careerists; and changing motivations over time.

Predominant or simultaneous motivations

Seminal research depicted people who voluntarily sought overseas work as comprising a relatively unskilled and transient youth culture motivated by adventure, novel experiences, and travel (Inkson et al., Reference Inkson, Arthur, Pringle and Barry1997). Research has since noted other issues as important to SIEs including family, financial, and career-related considerations (Lauring, Selmer, & Jacobsen, Reference Lauring, Selmer and Jacobsen2014; Richardson & McKenna, Reference Richardson and McKenna2006; Selmer & Lauring, Reference Selmer and Lauring2011; Suutari & Brewster, Reference Suutari and Brewster2000), but most research has continued to suggest SIEs are primarily motivated by personal and lifestyle goals (e.g. Doherty & Dickmann, Reference Doherty, Dickmann, Andresen, Al Ariss, Walther and Wolff2012; Doherty, Dickmann, & Mills, Reference Doherty, Dickmann and Mills2011; Thorn, Reference Thorn2009; Wechtler, Reference Wechtler2018). The current research supports some recent work (Nolan & Morley, Reference Nolan and Morley2014; Richardson and McKenna, Reference Richardson and McKenna2014) revealing SIEs are highly motivated by career-related desires, although in this current research some pursued simultaneous career and personal/lifestyle goals, and many were attracted to aspects of the chosen host country location. To fulfil such simultaneous motivations, SIEs approached their relocation holistically by aligning their career path with their personal/lifestyle desires to achieve personal learning, development, and growth. The SIEs in this study viewed self-initiated expatriation as a career-enhancing experience for accumulating portable and tradeable career capital.

SIEs as boundaryless careerists

The international career experiences of SIEs in this study resonates with characterisations of boundaryless careerists (Alshahrani & Morley, Reference Alshahrani and Morley2015; Biemann & Andresen, Reference Biemann and Andresen2010; Inkson et al., Reference Inkson, Arthur, Pringle and Barry1997; Jokinen, Brewster, & Suutari, Reference Jokinen, Brewster and Suutari2008). The SIEs independently chose to cross both country and organisational boundaries and exhibited a high level of agency in proactively shaping their careers. As in Jokinen, Brewster, and Suutari (Reference Jokinen, Brewster and Suutari2008) research, the SIEs placed importance on the development of career-related global networks and used the experience as a foundation to pursue a career in a foreign country. SIEs described their expatriation as a method for acquiring various competencies and global skills (cross-cultural, language and technical skills) and networks providing competitive advantage in the global labour market and for future employment.

The findings reveal three distinct subgroups of boundaryless careerists. First, those whom purposefully pursued mobility across organisational and national boundaries in unskilled temporary work. Second, those who pursued specialised career paths within their desired industry and exhibited strong career orientations marked by personal investment in their work and desire for upward mobility. Third, those who also pursued specialised career paths within desired industries but experienced barriers to gainful employment such as work permits; visa restrictions; poor local language skills; and lack of professional networks. Faced with an inability to secure preferred employment, many of the SIEs in the latter group undertook relatively unskilled, temporary work and were working below their capabilities to continue expatriation. The current research adds to the boundaryless career concept in highlighting those previously described in the literature as purposefully intending a boundaryless career and others (from this study) who involuntarily found themselves pursuing boundaryless careers in order to sustain their expatriation.

Changing nature of motivations

Addressing calls by Cerdin and Selmer (Reference Cerdin and Selmer2014) and Suutari, Brewster, and Dickmann (Reference Suutari, Brewster, Dickmann, Dickmann, Suutari and Wurtz2018) for further insight into the motivations of SIEs, and Brewster, Suutari, and Waxin (Reference Brewster, Suutari and Waxin2021) for insight into changing motivations, this research contributes knowledge in highlighting motivations of SIEs may change over time and reflect the interest in staying in or leaving the host country. Another study, which relied on retrospective accounts, suggested initial motivations of SIEs may become less relevant and harder to recall exactly after achievements (Pinto, Cabral-Cardoso, & Werther, Reference Pinto, Cabral-Cardoso and Werther2020). However, this current research studied SIEs who were mostly still in the early stages of their expatriation and were well able to recall their changing motivations. Some SIEs who were motivated to relocate abroad by intrinsic desires for adventure, travel, and personal challenge realised they could develop their boundaryless careers and thus their focus moved from personal/lifestyle factors to more career-related considerations. Some individuals who had relocated abroad to pursue professional employment later also valued lifestyle factors associated with the move.

Research has explored the degree of embeddedness of an individual in their work and local community (Biemann & Andresen, Reference Biemann and Andresen2010) and it has been suggested SIEs are less embedded in organisations (Linder, Reference Linder2018). The current research findings are important in suggesting SIEs make decisions about remaining in or leaving host locations (and staying with a current organisation) based on whether their actual experiences are in congruence with their initial motivations. AEs may potentially change motivations whilst on an international posting, they only have the choice to stay with their current posting/contract or leave the current employer. So, the insights about changing motivations are most relevant to the, arguably, much more globally mobile SIEs who can act on their changing motivations in many ways.

SDT in relation to SIEs' motivations and changing motivations

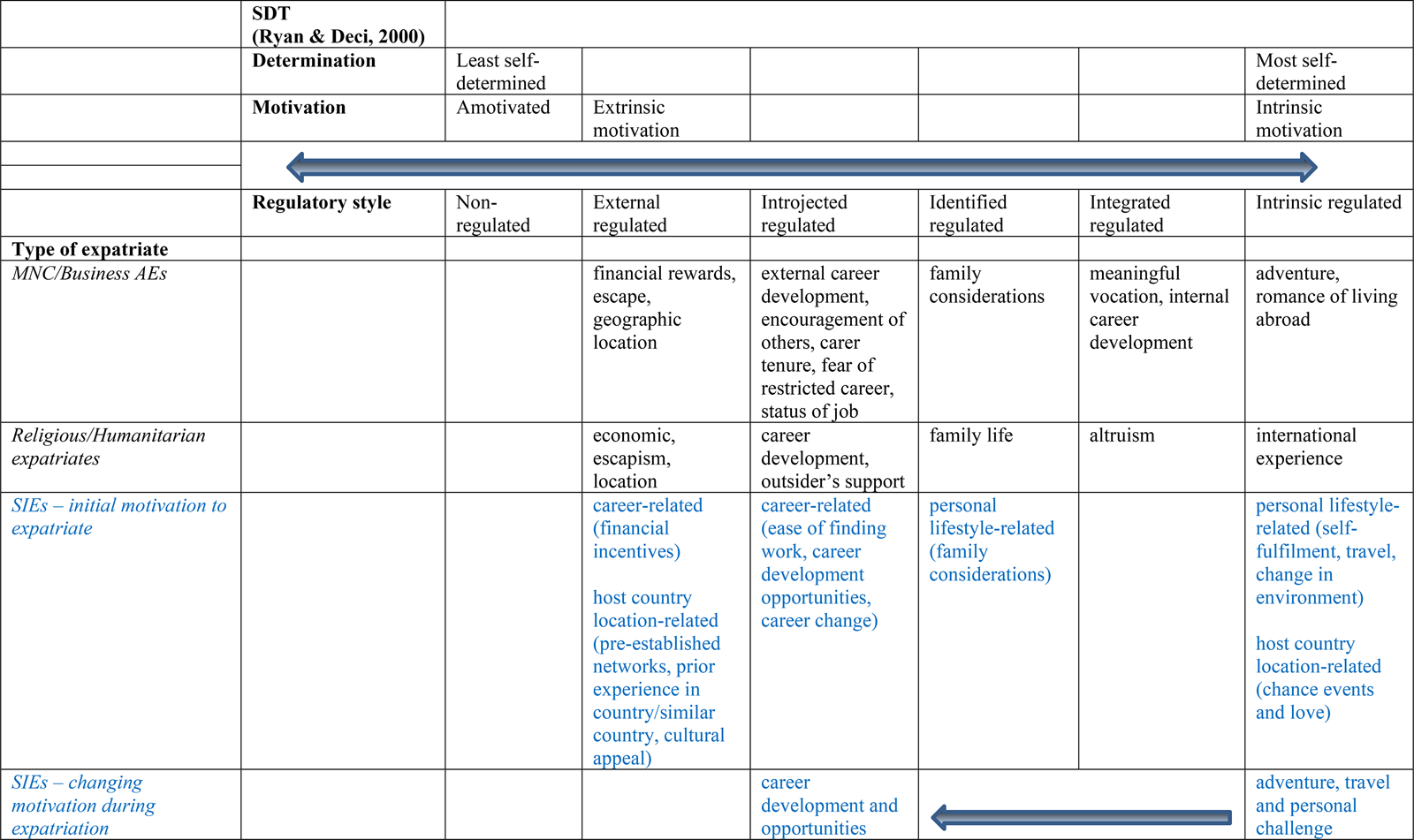

Though many of the motivating factors to expatriate apply equally to AEs and SIEs, SIEs may additionally be motivated by pre-established networks and cultural appeal of a particular country, and chance events and love. Though this current research supports earlier findings from the SIE literature, this research also makes a theoretical contribution in categorising motivations into career-related, personal/lifestyle-related and host country-related and mapping this against SDT. Moreover, this research demonstrates changing motivations in that, for some, a focus on personal/lifestyle factors shifted to include a focus on career. A figure previously developed by Oberholster et al. (Reference Oberholster, Clarke, Bendixen and Dastoor2013) which included motivations of multinational corporation (MNC)/business AEs and religious/humanitarian expatriates, was adapted to include SIEs' initial motivation to expatriate. Oberholster et al. (Reference Oberholster, Clarke, Bendixen and Dastoor2013) noted in their study that motivation for behaviour is dynamic and, like Brewster, Suutari, and Waxin (Reference Brewster, Suutari and Waxin2021), suggested that reasons for initially expatriating may differ from reasons to continue with expatriation assignments. Thus, the figure was also adapted and extended to include how SIEs' change motivations during expatriation (see Figure 2).

Fig. 2. Motivations and changing motivations of SIEs.

Source: Adapted from Oberholster et al. (Reference Oberholster, Clarke, Bendixen and Dastoor2013).

The motivations that are career-related (ease of finding work, career development opportunities, carer change) are categorised as extrinsic introjected regulated whilst career-related (financial incentives) are categorised as extrinsic external regulated. The motivations that are host country-related (pre-established networks, prior experience in country/similar country, cultural appeal) are categorised as extrinsic external regulated whilst host country-related (chance events and love) are categorised as the most self-determined intrinsic regulated. The motivations that are personal lifestyle-related (self-fulfilment, travel, change in environment) are categorised as the most self-determined intrinsic regulated whilst personal lifestyle-related (family considerations) are categorised as extrinsic identified regulated. The changing motivations encapsulate a shift from self-determined intrinsic regulation (adventure, travel, and personal challenge) to extrinsic introjected regulated (career development and opportunities).

Contributions, implications, and future research

Research and theoretical contributions

This research provides an important theoretical contribution to the SIE literature and responds to calls to offer further insight into the motivating factors driving international work especially self-initiated expatriation (Doherty, Richardson, & Thorn, Reference Doherty, Richardson and Thorn2013; Lauring, Selmer, & Jacobsen, Reference Lauring, Selmer and Jacobsen2014; Suutari, Brewster, & Dickmann, Reference Suutari, Brewster, Dickmann, Dickmann, Suutari and Wurtz2018) and, in particular, SIEs' changing motivations (Brewster, Suutari, & Waxin, Reference Brewster, Suutari and Waxin2021). In answering the research question: Why are Australian SIEs motivated to expatriate to South Korea or the United Kingdom? the research found although SIEs are motivated to pursue personal/lifestyle factors (self-fulfilment; travel; family reasons; and desire for a change in environment), such desires are secondary to, or alongside, career-related factors (career-development opportunities; financial incentives; and desire to pursue career change). In pursuing simultaneous motivations, SIEs exhibit strong career orientations marked by personal investment in their work and desires for upward career mobility and proactively shape their careers across multiple organisations, occupations, industries, and national boundaries.

This research extends knowledge by providing greater conceptual clarity about the boundaryless careers of SIEs. The research highlights some SIEs deliberately pursue mobility though their internal career whereas others accept boundaryless careers to continue with expatriation and they move boundaries and adapt their carers within an individual international experience. This current study shows that, although many of these SIEs were attracted to host country characteristics, an individual might expatriate for one range of motivating factors but over time another set of factors might evolve affecting the desire to leave, or remain within, the host country. This finding about changing motivations extends the literature by suggesting SIEs make decisions about staying or leaving host locations based on assessments of the value of their experiences and achievement of intended goals. The research makes a theoretical contribution in examining SIEs' (changing) motivations through the lens of SDT. Earlier research included an analysis of the extrinsic and intrinsic motivations of MNC/business AEs and religious/humanitarian expatriates (Oberholster et al., Reference Oberholster, Clarke, Bendixen and Dastoor2013). The current research extends this to provide an analysis of SIEs' initial and changing motivations to expatriate including the most self-determined intrinsic factors and a range of lesser self-determined extrinsic factors. Finally, this research contributes to the literature not just in exploring SIEs, a growing and important cohort in the global talent pool, but focusing on Australian SIEs, in South Korea and the UK, economies of growing importance globally and in which expatriation has received scant attention.

Implications for organisations

Prior research has suggested SIEs may lack organisational commitment and present difficulties for HR planning, retention, and talent management (Biemann & Andresen, Reference Biemann and Andresen2010). This research found SIEs can be very career-focused and even when they initially relocate for personal/lifestyle factors they may become more career-oriented during their expatriation. Global competition to attract and retain SIEs by international organisations is likely to continue as they are often less costly than AEs and have cultural knowledge of, and affinity with, contexts. Thus, it is important for organisations to ensure career opportunities, compensation and support meet SIEs' motivations. In managing SIEs who are career motivated, organisations should ensure jobs assigned to their SIEs are appropriately challenging and matched to competencies and provide appropriate career paths. For SIEs motivated by personal/lifestyle factors, organisations could consider fulfilment of SIEs' needs via flexible working hours and opportunities to travel for work (providing adventure and learning). Schuster, Holtbrügge, and Engelhard (Reference Schuster, Holtbrügge and Engelhard2019) found inpatriates who primarily accepted inpatriation for extrinsic motivations (career-related) engage more in knowledge sharing. As SIEs tend to have greater cultural affinity and language/cultural competency for the country to which they relocate, it might be expected they would engage more in knowledge sharing with locals even when their primary motivation for relocation was for more intrinsic reasons. This should be considered by organisations when recruiting and developing these international employees.

Limitations and issues for future research

Despite the richness of data collected from lengthy interviews with 58 SIEs, research limitations are acknowledged. First, the research had a purposive sampling strategy in respect to seeking SIEs within two years of relocation and it was expected participants would be recruited across a diverse range of industries. Though the participants were employed across many industries, amongst those who had self-initiated relocation to South Korea, there was a larger percentage of individuals working within the education industry. This reflects individuals self-selecting to participate in the research and not deliberately recruiting specific numbers from particular industries. South Korea has actively recruited foreigners who speak languages other than Korean and to improve international relationships and education is one of the most in demand industries for foreign nationals (Internations, 2021). Further, though Australia has a relatively small population of 26 million, earlier research has found that Australian SIEs are well represented amongst educational professionals working in South Korea (Froese, Reference Froese2012). Moreover, through the use of a snowball sampling strategy, as some of the initial participants that were living in South Korea were working in education, this resulted in referrals to others in the education industry. Given that these individuals were interested in discussing their SIE experiences interviews were undertaken with them even if it resulted in a sample skewed towards people working in education. There were variations between those employed in primary, secondary, and tertiary levels in both the public and private sectors, and across employee type, from teachers to tenured academic staff to business owners. However, future research might use a purposive sampling strategy focused on specific industries in South Korea that were not reflected in this research. Moreover, future studies could include a wider range of destination countries and include experiences of SIEs in not-for-profit organisations and non-government organisations.

Second, the study involved perspectives of self-selected participants. There is value in also examining views of their spouses and managers. It would be beneficial, particularly, to consider different perspectives of spouses who were working or not working, their involvement in the choice for the expatriate to relocate, and the implications for their own careers especially for those who had worked prior to relocation and were not working in the overseas location.

Third, this study highlighted SIEs who were motivated to relocate internationally for personal/lifestyle reasons but remained overseas for careers so it would be valuable for future research to identify SIEs who expatriated to further their self-initiated (boundaryless) careers but who then who had reduced interest in career and instead stayed overseas for personal/lifestyle reasons.

Fourth, though this study found young SIEs reported strong career achievements, it is acknowledged the study included a significant number of younger people and they might be expected to have changing motivations as they are in the earlier stages of their career development as well as developing personal relationships. It could be speculated people in middle age and towards the end of a usual career span are also likely to have changing motivations (just as they are also likely to change career direction in self-initiating expatriation), Thus, it is suggested future research with a larger cohort and more diverse age groups, might specifically examine changing motivations while working internationally, according to life stages.