Peasants are a fundamental part of African historiography, yet the historiographical debate has stalled in recent years. This stasis prompts the imperative to revisit African peasantries and locate their colonial encounters within the structural precincts of classical ‘peasant agency’ theory. There is a need to engage with how peasant agency was constrained in settler colonies by structural factors such as commodity asymmetries, cash crop hierarchies, and global market forces. The 1960s and 1970s scholarship on peasant studies and colonial development and underdevelopment in Africa underestimated the role of peasants as historical actors and collapsed the complex processes of rural transformation into a single trajectory of ‘strangulation’ and collapse.Footnote 1 However, new approaches to African peasant studies foregrounded peasants’ ingenuity in navigating the complex disruptive colonial infrastructure and highlighted peasant agency to emphasize how enclaves of peasant production survived the colonial economic onslaught and fomented centres of rural resistance, rural entrepreneurship, and political consciousness.Footnote 2

Despite foregrounding agency, this scholarship stressed the ubiquitous structural constraints under which peasants operated at various levels and how these constraints impinged on their limited choices.Footnote 3 John Lonsdale referred to this embedded pervasive precarity and intractable dilemma of African producers in hegemonic colonial and neo-colonial capitalist world systems as ‘agency in tight corners’.Footnote 4 Thus, while there were moments of African prosperity and independent production of cash crops, these transient episodic booms were structured by and subject to the broader colonial relations and institutional arrangements that predisposed African peasantries to eventual collapse and failure. In this paper we interrogate cash crop and commodity asymmetries within the colonial economy as structural constraints on peasant agency. Each cash crop or agricultural commodity occupied a unique space within the matrix of colonial economic and political power relations in Africa and these power asymmetries were based on the respective export value and the concomitant economic influence it bestowed upon white settler power.

A cursory perusal of agricultural archives reveals how settler colonial states in Africa systematically triaged cash crops and agricultural commodities into hierarchies. These were not only based on dispassionate economic calculations, but also invested with notions of what was ‘right’ and what was ‘might’ — what was fitting and what was hegemonic. In essence, they were invested with tacit ideologies of power and powerlessness, domination and subservience, knowledge and ignorance — evinced in their production and marketing. These commodity asymmetries concomitantly mediated peasant agency, accumulation patterns, and peasant options in the countryside. High value export cash crops and commodities such as coffee, tea, and tobacco, that were the basis of white economic power and privilege in settler colonies, were often subjected to more stringent production and marketing controls deliberately meant to exclude African producers and entrench specific paradigms of development that benefitted white settler interests. In some instances, Africans were banned from participating in the production of high value export crops for much of the colonial period. Meanwhile, commodities with a low value in the hierarchy of colonial economic power relations, because of their lower unit returns on the global export market (such as cotton), were often used by the colonial state to entrench domination of peasantries through the stick of coerced production or, more often as time went by, the carrot of state subsidies to peasant producers.Footnote 5

In settler colonies such as Kenya and Southern Rhodesia, export expansion targeted white farmers to create a monopoly in the cultivation of high value export crops while restricting Africans from those crops to ensure supply of labour to white farms. By the late 1940s though, with new global and local pressures such as festering nationalism, rural discontent, and postwar booms in agricultural commodity prices, colonial policy on high value export crops altered to allow a cautious and guided entry of African cultivators in a way that would not disrupt the status quo and imperil white settler agriculture.

In this paper we engage with how cash crops were constructed in the colonial state and given a significance that controlled relations of production and the changing dimensions of African participation in commodity production that, in turn, impacted on the possibilities of peasant agency. Using this framework, we examine African tobacco producers in Southern Rhodesia chronologically across three distinct periods: a precolonial to early colonial period of independent production and boom (the early 1900s through the late 1930s); an era of state curtailment of peasant modes of production and decline of African participation in the tobacco economy (the 1930s through the 1950s); and, lastly, a period of colonial state-assisted African production of Turkish tobacco (1952 through 1980).Footnote 6 The first period witnessed an ephemeral boom for African peasants because of the domestic market provided by emerging mining settlements and towns. The second period marked the collapse of production and trade in ‘indigenous’ African tobacco as the state systematically pushed Africans out of production through restrictive statutory interference in production and marketing as well as the introduction of Western cigarettes. The third period saw the initiation of African production of Turkish and Burley tobaccos, and their integration for the first time into the global export economy under the colonial state's modernistic agenda to transform African agriculture and cash crop production.Footnote 7

There is also scant historical literature on the participation of Africans on tobacco production in Southern Rhodesia beyond their role as labourers on the white settler farms.Footnote 8 The only historical work on the subject is Barry Kosmin's early colonial study that ends in 1938 and misses the integration of peasant producers into the global export market between 1952 and 1980.Footnote 9 We argue that, although colonial policy towards African tobacco producers shifted across the twentieth century from curtailment to encouragement, it was nevertheless enduringly informed by the imperative to restrict Africans to certain types of tobacco that would not challenge European tobacco farmers or lead to the rise of an independent African agrarian bourgeoisie that could compete with white settler farmers.Footnote 10 Thus, at all points during the colonial period, the African peasant producer was enmeshed within a complex global and local economic infrastructure in which he was susceptible to failure, and remained economically marginal and vulnerable.

From incentives to curtailment? The rise and fall of an African tobacco economy in Southern Rhodesia, 1904–38

The cultivation of tobacco in Africa predates colonialism. By the end of the seventeenth century the crop had penetrated much of the continent as a result of Portuguese, French, English, and Arabic trade networks.Footnote 11 The traditional species of tobacco cultivated in Africa was Nicotiana rustica. Footnote 12 In the area that came to be known as Southern Rhodesia, Africans began cultivating tobacco from at least the fifteenth century when it was introduced by Portuguese traders.Footnote 13 Its cultivation during the later parts of the precolonial period is well documented in historical accounts.Footnote 14 For example, Thomas Morgan Thomas of the London Missionary Society, in memoirs of his adventures in Southern Africa between 1864 and 1873, records that Ndebele people grew large quantities of tobacco: ‘indeed I cannot remember seeing a single village around which there were no tobacco gardens’. Footnote 15 Tobacco was integral to the cultural rituals of the Ndebele people who took it as snuff and smoked it in ingiti (clay pipes) and igudu (smoking horns). Africans cultivated and irrigated patches of tobacco in their gardens for their own consumption, for barter, and for annual tribute to the king.Footnote 16

Tobacco was the first important ‘European crop’ that was cultivated by the pioneer white settler farmers as early as 1893.Footnote 17 The British South African Company (BSAC) developed an interest in tobacco production for colonial economic growth and sampled ‘indigenous’ African tobaccos to ascertain their potential commercial value.Footnote 18 The Company concluded that this tobacco had no export value since its flavour was alien to British consumers.Footnote 19 Consequently, white settler farmers began to cultivate ‘superior’ varieties of Tabacum (flue-cured, Turkish, and fire-cured) from American seeds while Africans cultivated the ‘inferior’ rustica for the peripheral domestic market.Footnote 20 Africans could only interact with the European types of tobacco as labourers, not as producers.Footnote 21 The growing of tobacco became particularly important from around 1908, when the colony's company administration launched a White Agricultural Policy (WAP).Footnote 22

Tobacco became a symbolic agricultural commodity conveying white power and privilege.Footnote 23 Buoyed by the fortunes offered by the Union of South Africa's market, white settler tobacco production expanded significantly. In 1914, 2.2 million lbs of tobacco were exported to the Union's market. This rose to nearly 10 million lbs in 1928.Footnote 24 The United Kingdom's granting of an imperial preference for empire tobacco from 1919 expanded the export market for Rhodesian tobacco, prompting production to reach 14 million lbs in 1928 and resulting in white settler tobacco production contributing 42.7 per cent to agricultural export revenue.Footnote 25 Tobacco was second only to gold in aggregate value of all exports in Southern Rhodesia between 1916 and 1947, accruing nearly 43 million pounds sterling.Footnote 26

While the settler export tobacco market expanded, the cultivation of indigenous Inyoka tobacco amongst African peasants (who grew it together with other crops such as maize) continued. The exact size and scale of the precolonial Inyoka tobacco trade and economy cannot be ascertained because of limited records, but historical evidence does suggest that there was a significant manufacturing and tobacco trade economy.Footnote 27 This tobacco economy developed from around 1899, as European traders bought stocks of tobacco to resell on the mines, providing African peasants with money to pay taxes and accumulate wealth.Footnote 28 Indeed, the role of tobacco as a ‘progressive crop’ that provided economic opportunities for smallholder and peasant producers and prevented their proletarianisation into the colonial wage labour economy has received a lot of scholarly attention.Footnote 29 However, the resultant pecuniary gains to the prosperous peasant Inyoka tobacco economy restricted the flow of Africans into wage employment — which outraged some key colonial officials just when African labour was most desired for white settler tobacco production.Footnote 30 Between 1922 and 1938, this lucrative African tobacco economy declined precipitously as a result of the penetration of the African market by European cigarettes and lack of state support at a time when the state was subsidizing the growing European tobacco sector.Footnote 31 The decline of the Inyoka tobacco economy was contemporaneous with the decline in African peasant production that happened in Southern Rhodesia, and in most African colonies, during the 1930s, as ‘the further development of settler capitalism could no longer contain the very peasantries it had created’.Footnote 32 In Southern Rhodesia, the competitiveness of African producers was purposefully stymied through land alienation, and the state-imposed centralisation and conservation models codified more effectively by the 1930 Land Apportionment Act (LAA).Footnote 33 However, the early Inyoka tobacco industry remained outside much of the state centralisation and conservation injunctions of the 1930s. The industry was a feature of the precolonial system and its cultivation methods were adapted to its environment.Footnote 34 The region where Inyoka was cultivated in southwestern Zimbabwe was dry, infested with tsetse flies, and lacking ‘modernisation’ such as water schemes or agricultural demonstrators in the production methods of their tobacco.Footnote 35 In essence, this tobacco economy remained outside the global export network, isolated from the white settler tobacco economy and the orbit of state agricultural policy in its marketing and production. Nevertheless, its autonomy was dependent on extraneous variables such as stable global market dynamics balancing with local production in white farms and averting the need to dispose of tobacco on the local market space where Inyoka thrived. This began to change after a 1914 glut precipitated a tobacco slump that ruined white growers.Footnote 36 The slump prompted the colonial government to prioritise securing the local market for poor grades of tobacco produced in white farms through the imposition of a cigarette tax on Rhodesian cigarettes sold on the local market. It was pointed out during the course of the debate on the tax by one of the directors of the BSAC, Earl Grey, that the tax would be paid for by the ‘native’ consumer and not the grower, since the habit of smoking cigarettes was growing amongst natives due to the availability of cheap locally made cigarettes in ‘penny packets’.Footnote 37 The state's anxiety about the increasing supply of ‘native’ tobacco on the domestic market escalated in the 1930s, as a 1928–30 tobacco export market slump destroyed European tobacco growers.Footnote 38 The slump was so severe that the contribution of tobacco to agricultural exports fell from 46.4 per cent in 1927 to 17.4 per cent in 1930.Footnote 39 Subsequently, an investigation into the ‘native’ position in the tobacco industry was initiated in 1931 so as to seek ways to promote local manufacturing for domestic consumption.Footnote 40

Reports by native commissioners on ‘native’ tobacco during the 1930s all concurred that there was gradual collapse of the Inyoka tobacco industry from 1934, attributable to an African preference for European cigarettes.Footnote 41 These reports unanimously point to ‘little trading of tobacco’ by ‘natives’, and a decrease in the practice of smoking Inyoka tobacco in the mines, as Africans now preferred a cheap type of tobacco they could roll into cigarettes.Footnote 42 The decline in the smoking of Inyoka tobacco in Southern Rhodesia follows a trend found in most parts of colonial Africa, Asia, and America where the consumption of traditional tobacco products was disrupted by the introduction of the modern cigarette industry during the twentieth century.Footnote 43 Demand for cigarettes amongst Africans was stimulated through their portrayal in advertisements as a class symbol of urban sophistication, and an escape from the countrified antediluvian living represented by coarse Inyoka tobacco. The nucleus for the African tobacco market was built by creating demand and ‘getting the African into the habit of smoking’.Footnote 44 This was done through the handing out cigarettes as presents to African labourers, and the opening of retail shops on farms and mines which distributed cigarettes to whet the appetite amongst Africans.Footnote 45 Most white miner owners gave their African labourers weekly rations of tobacco for ‘excellence of work’ and added motivation.Footnote 46 The consumption of tobacco amongst African mine workers was also popularised by a curiously widespread but erroneous medical opinion amongst white mine owners that smoking could cure scurvy.Footnote 47 It was believed that the disease was a mental affliction that could be disposed of ‘as soon as a “boy” buys a six-penny pipe and learns to smoke’.Footnote 48 The increased popularity of cigarettes and European tobacco on mines significantly affected the indigenous tobacco economy over time (see Fig. 1, above). Inyoka marketing statistics show that the amount of tobacco purchased by traders declined significantly from 7,980 lbs in 1934 to just 560 lbs in 1938, as a result of the promotion of domestic manufacture of cigarettes for local consumption by the state.Footnote 49 Simultaneously, tobacco sales from purchases by traders dropped precipitously in value from 234 to just 8 pounds sterling. However, over the same period, the amount of tobacco hawked by the growers increased from 26,220 lbs to 51,000 lbs.Footnote 50 By 1938, the sale of the Inyoka tobacco by traders had ceased in the mines. Consequently, from 1939, the native commissioners’ reports are silent on Inyoka production as it had receded into an informal almost black-market entity.Footnote 51

Fig. 1. Inyoka tobacco production and trade by Africans in Southern Rhodesia, 1906–38.

Source: Kosmin, ‘The Inyoka tobacco industry’, 281.

While historians like Gary Blank have contended that the Inyoka tobacco industry prospered until the 1960s, there is no oral or archival evidence to support that inference.Footnote 52 In fact, the crop disappears from the official colonial sources thereafter, and Kosmin could only surmise that all the vestiges of its production had been virtually wiped out by the 1960s.Footnote 53 Also, as other sources have shown, the Shangwe area became famous for cotton production (and not tobacco) during the rest of the colonial period and, indeed, even up until today.Footnote 54 However, although Kosmin attributes the decline of the African tobacco economy to a shift in taste and preference for European cigarettes and the marketing infrastructure set up by the colonial state, there were other more disruptive legislative tools that were enacted to force Africans out of production. These policy regulations were constructed to disrupt African tobacco producers and push them into the colonial labour market.

State curtailment of African peasant tobacco production in Southern Rhodesia, 1930s–1950.

The 1930s marked the low point for the agricultural viability of peasantries in Southern Rhodesia as African commodity production was severely curtailed to stem the tide of ‘native’ competition on European agriculture. Although the impact of this policy varied from crop to crop, the discrepancies between tobacco and other crops was particularly marked. While other commodities like beef and maize suffered the harsh effects of state curtailment policy in Southern Rhodesia during the 1930s, enclaves of peasant production still survived and even boomed during the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s.Footnote 55 African cotton production under state subsidies flourished such that by 1949 peasant cultivators produced cotton with an export value of £156,650.Footnote 56 At the same time peasant grain production gained so much momentum that by the mid-1950s African farmers produced twice as much maize as European farmers.Footnote 57 Other crops such as ‘kaffir corn’, munga (millet), groundnuts, and beans grown in African areas also expanded in production during the same period. Meanwhile amongst African peasants tobacco was being cultivated on less than 1,000 acres of land.Footnote 58

In 1936 the government emphasised the value of integrating African producers into world markets, but insisted this had to be limited to ‘those crops which Europeans cannot produce at world prices’ and Africans had to be assisted only to produce ‘certain crops’ such as cotton, maize, and peanuts.Footnote 59 Consequently, crops that Europeans could produce at ‘world prices’ or produce for the export market profitably, such as tobacco, remained on the peripheries of African peasant production. Resultantly, while crops such as maize, groundnuts, rapoko (finger millet), and cotton did relatively well in African areas, tobacco remained an almost invisible commodity within the production and marketing matrix of African peasants, as Figs. 2 and 3 show below.

Fig. 2. Crop production in African areas of Southern Rhodesia, 1948–58.

Source: Yudelman, Africans on the Land, 241.

Fig. 3. African production of Turkish tobacco, 1951–8.

Source: Yudelman, Africans on the Land, 241.

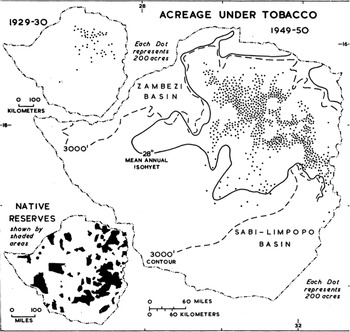

Yet tobacco still occupied a higher place within the export hierarchy of agricultural commodities in Southern Rhodesia.Footnote 60 In 1940, tobacco accounted for 15 per cent of total exports, and in 1944 the crop contributed 54 per cent of the gross value of agricultural exports.Footnote 61 A postwar tobacco boom expanded the export market for Rhodesian tobacco, resulting in lucrative earnings, capital build-up, and an expansion of area under tobacco production on white settler farms, see Fig. 4 below.Footnote 62 By 1947, tobacco had overtaken gold as the colony's chief export, contributing more than a third to total export receipts.Footnote 63 By 1961, of the £55.6 million total value of agricultural production tobacco contributed 56 per cent, maize 13.8 per cent, beef 12.4 per cent, and all other crops a combined 18.1 per cent.Footnote 64

Fig. 4. Tobacco acreages in white settler farms in Southern Rhodesia, 1930 and 1950.

Source: Scott, ‘The tobacco industry’, 190.

The significantly higher export value of tobacco compared to other crops prompted the state to be more ruthless in curbing Africa peasant participation, through systematic marketing and production regulations, to ensure white settler production hegemony. The state reckoned that the global export market could only be secured by an unsullied reputation of the quality of Rhodesian tobacco to overseas manufacturers to ward off competition from American producers. Entry of Africans was believed to compromise the export market through production of poor quality tobacco. So to preempt this ‘catastrophe’, the state legislated against African production.Footnote 65 In 1933, the Tobacco Pest Suppression Act compelled all tobacco farmers to ‘clean their lands’ by uprooting stalks by the first of August of each year to control the spread of diseases.Footnote 66 Although this law had universal application to all farmers irrespective of race, it was used to target Africans’ tobacco crops which were considered a risk to white growers because ostensibly they spread diseases and pests.Footnote 67 Police patrolled ‘native areas’ and were ordered to uproot and destroy all ‘native crops’ not grown in accordance with the law.Footnote 68 In Nyasaland, similar methods were used during the 1930s when the Department of Agriculture hired gangs to uproot African tobacco gardens to prevent overproduction.Footnote 69 Also, in Kenya the supposed threat of pests and diseases in African-grown coffee, endangering European-grown coffee and ruining the global credibility of Kenyan coffee, was used to justify the marginalisation of Africans from coffee production until the mid-1930s.Footnote 70

Another statute that restricted African peasants’ entry into tobacco production in Southern Rhodesia was the Tobacco Market and Stabilisation Act of 1936. Although touted as a panacea for the production and marketing chaos within the tobacco industry, this law actually forestalled the entry of Africans into commercial production of tobacco through a byzantine regulative regime. The act gave power to the Tobacco Marketing Board (TMB) to licence tobacco farmers, auction floors, and buyers, and centralised controlled sales.Footnote 71 The regulative framework established by this act discouraged Africans from getting into commercial export production by making it impossible for them to get growers’ licences. The act was so antithetical to the interests of ‘native’ tobacco producers that one native commissioner described it as ‘class legislation’ that was solely crafted to marginalise African growers to stop them from raising taxes by selling their tobacco.Footnote 72 Although the law could not interfere with Africans as long as they did not enter commercial export production of European tobaccos, it was framed as a dormant deterrent to the existential threat of African competition in the production of European tobacco.Footnote 73 The restrictions to African participation in production of certain high value cash crops informed state policy in settler colonies and this was sometimes done through registration licences and administrative arrangements. In Kenya, for example, African production of pyrethrum and coffee was curtailed until the 1950s through levying of an expensive annual licence fee.Footnote 74

The state in Southern Rhodesia was also always wary of the detrimental effects of ‘native’ production on the labour demands of settler tobacco producers but couched their anxieties in terms of black disease and white purity.Footnote 75 The labour crisis hit the mining and agricultural sectors in Southern Rhodesia severely during the 1930s, compounded by competition from South African gold mines offering higher wages.Footnote 76 Labour shortages and the ‘labour question’ had a significant impact: labour deficits of between 15 to 85 per cent were recorded in most farming districts of the colony during the 1930s.Footnote 77 By the war years, the state had to assuage the labour crisis in the white settler farms through coercive recruitment and compulsory conscription of African labour, since peasants were unwilling to abandon independent farming in the reserves. Similar concerns preoccupied the colonial state in Nyasaland, where land concentration by white tobacco estates’ owners in the Southern region beginning in 1920 was used as a tool to control and coerce African labour through the notorious labour exploitation regime known as thangata.Footnote 78 The role of land tenure regimes and control over access to land for the prosperity of peasant tobacco production has been highlighted in Latin American historical literature.Footnote 79 Abundance of land and low population densities in Latin American tobacco producing areas meant that the state was unable to compel peasants to consolidate tobacco production or reform production techniques. This led to the emergence of a strong, independent, and prosperous peasantries who could not be coerced into the wage labour economy, as was the case in Southern Rhodesia and Nyasaland.

Production of tobacco by Africans in Nyasaland had in fact jeopardised the smooth flow of migrant labour to Southern Rhodesia in the 1920s. In 1926, colonial labour recruitment officials announced worriedly that there had been a dramatic drop in the numbers of African migrant labourers crossing into Southern Rhodesia.Footnote 80 This was attributed directly to the cultivation of tobacco by Africans in Nyasaland, who were earning enough money to pay their taxes.Footnote 81 In Nyasaland, the state created the Native Tobacco Board in 1927 to regulate African production and save the European growers.Footnote 82 However, unlike in Southern Rhodesia (where regulations prevented Africans from growing European tobacco), in Nyasaland independent producers were able to flourish and obviate the Native Tobacco Board.Footnote 83 These disparities can be accounted for by the different institutional arrangements in tobacco production and marketing. In Nyasaland much of the settler tobacco production and marketing was controlled by companies. These companies would often buy African tobacco outside the Native Tobacco Board at cheaper and more exploitative prices to resell at a bigger profit.Footnote 84 From the early 1930s white growers in Southern Rhodesia were wary of how company-controlled production and marketing had ruined European growers and handed production to Africans.Footnote 85

Another unique feature of African production in Nyasaland, was the rise of visiting African tenancy and sharecropping in the central province from the late 1920s, as estate owners contracted landless Africans to produce tobacco on their farms.Footnote 86 Whether this system encouraged the rise of a more prosperous group of peasant growers than in the crown lands is debated.Footnote 87 However, it was still based on exploitative extraction of labour and was excoriated by African nationalists during the 1950s. It must also be remembered that the visiting African tenancy system in Nyasaland arose out of the collapse of settler plantation agriculture during the 1930s and the fractured nature of white settler tobacco farming due to lack of private technical assistance and state support. However, in Southern Rhodesia, the existence of economically stronger, better organised white settler tobacco farmers, actively supported by the state and controlling production and marketing, precluded the emergence of sharecropping and African tenancy. Meanwhile, in Northern Rhodesia from 1900 to 1937, Africans were simply banned from growing tobacco — although they were allowed to grow maize and other crops.Footnote 88 The Macdonell Reserves Commission of 1924 pointed out that flue-cured tobacco was ‘beyond the scope of the native’, as Africans had neither the capital nor the training for it.Footnote 89

Therefore, state policy on tobacco production was predicated on creating a relationship of white planters as producers and Africans as labourers and consumers. A small thriving white planter community and a viable capitalist sector was established at the expense of the African peasantry. In Southern Rhodesia, this curtailment resulted in the collapse of African commercial production of ‘indigenous’ tobacco or, indeed, any tobacco from around 1938. The anomaly presented by tobacco compared to other agricultural commodities is striking. The curtailment of African cash crop production by colonial officials from the 1930s was usually framed around the imperative not to completely vanquish or annihilate African production but to nurture enclaves of peasant production that were too weak to compete with the established white capitalist sector. This, as the economic historian Paul Mosley contends, was the cornerstone of the settler state policy for maize and beef production in Southern Rhodesia (and Kenya): the European producer was supposed to be protected against the competition of the African without hitting the African producer too hard since there were influential sectors of the European economic sectors that benefitted from African cheap supplies of grain and beef.Footnote 90 With other cash crops such as tobacco that occupied a higher value in the colonial export hierarchy, the state adopted a much more sustained and systematic curtailment policy, with the result that the African tobacco economy in Southern Rhodesia collapsed from the late 1930s. The integration of African tobacco producers into the export economy only began in 1952, at the behest of the colonial state during a time when the British imperial government was emphasising high modernism and state planning. But, even then, Africans could produce only those types of tobacco which least interested European farmers.

From curtailment to assistance? African Turkish tobacco production and the state in Southern Rhodesia, 1952–80.

During the 1940s and 1950s British colonial Africa initiated a series of programs emphasising the merits of modernism, state planning, and increasing productivity through technical innovation.Footnote 91 Western science and top-down technical programs became the fulcrum of state intervention in the agrarian landscape in most parts of British colonial Africa, tied to the desire to increase production for postwar reconstruction.Footnote 92 Beyond the rhetoric of development, high modernism and state planning had an international political aim of controlling rural populations in the countryside through market-led developmentalism and land tenure reform.Footnote 93 This was largely placatory within the context of the spread of communism, the rise of nationalism, and peasant unrest in most parts of Africa, Latin America, and Asia.Footnote 94 Thus, during the 1940s and 1950s, colonial officials’ position on peasant communities began to change, as the interests of white settlers shifted from demand for agricultural labour to the desirability of a settled industrial labour force, rural security, and a stable and productive but ultimately uncompetitive African peasantry.

Although much of the modernism rhetoric was expressed in the colonial jargon of ‘rural development’, ‘peasant cash crop production’, and soil conservation, the corresponding projects were tools for political control of rural populations. In Kenya, the Swynnerton Plan was launched in 1953, ostensibly to transform the African peasantry through land consolidation, soil conservation, and the encouragement of cash crop production.Footnote 95 It was espoused as the end of racial discrimination in agriculture, a joint enterprise of all races in the development of productive capitalist agriculture.Footnote 96 However, in reality, the political pressures brought by the Mau Mau uprisings and the state of emergency had compelled the colonial state on the expedient path of modernism. The colonial state implemented perfunctory and piecemeal rural reforms, aimed to consolidate a class of technologically progressive but politically conservative and quiescent African yeomen who might act as a buffer against subversive rural elements.Footnote 97 In 1944, the Native Trade and Production Commission in Southern Rhodesia recommended coercive enforcement of good husbandry methods in the native reserves to prevent land degradation, overstocking, and ‘ruinous farming practices’.Footnote 98 These recommendations were later codified by the Land Husbandry Act (NLHA) in 1951, reconfiguring land tenure in African areas both spatially and politically.Footnote 99

The implementation of modernisation meant that the colonial state had to find suitable agricultural commodities and cash crops that could be promoted in African areas, with the potential to generate capital investments and raise the standard of living. Peter Wagner conceived of the promotion of this policy as ‘organised modernity’ meant for the dual role of servicing post-war imperial self-sufficiency and metropolitan markets.Footnote 100 Ultimately, this new thrust in colonial agricultural policy realigned cash crop relations of production, as the colonial state became more amenable to Africans’ participation in the agricultural export economy. As the apathy of the 1930s thawed, colonial governments started to encourage peasant cultivation of such crops as coffee, pyrethrum, tobacco, and tea to transform rural areas. On the other hand, export revenue from cash cropping would also conveniently pay for the coercive superstructure of postwar African administration. It was within this context that the state in Southern Rhodesia also altered its attitude to African production of tobacco. Suddenly, tobacco became the right crop for African peasants to encourage new patterns of rural accumulations, land development, and soil conservation.

However, beyond the modernisation and technical side there were other factors that compelled the state in Southern Rhodesia to change its policy: global market forces and local production dynamics. During the 1950s there was a huge demand for Turkish tobacco on the international tobacco market, caused by the rising popularity of blended cigarettes such as Camels, Lucky Strikes, and Chesterfields. Concurrently, the postwar boom in flue-cured tobacco prices caused a significant decline in Turkish production amongst white growers.Footnote 101 Facing an uncertain future but still guaranteed a viable global market, the Turkish tobacco industry was rescued by encouraging African peasant production. Even then, the Rhodesia Tobacco Association (RTA), a body of exclusively white growers, was perturbed by the initiative to encourage Turkish production in African areas and noted with concern that ‘the great inflow of cash to the reserves would deplete the already scanty labour supply’.Footnote 102

So, in 1952, the state launched a pilot scheme for Turkish tobacco production in the Musengezi Native Purchase Area (NPA) with twenty pioneer African farmers growing the crop on half-acre plots.Footnote 103 NPAs, set up in 1931 under the LAA to encourage ‘progressive African farming’, had better land and were less congested than native reserves.Footnote 104 In 1954 the scheme was further extended to cover seventy African farmers in four other purchase areas.Footnote 105 Predictably, there was no attempt to encourage African production of Virginia flue-cured tobacco, ostensibly because ‘the capital costs involved would be a big deterrent to the farmer’.Footnote 106 The 1962 report on African agriculture pointed out that Virginia flue-cured tobacco was grown almost entirely by white farmers (with the exception of just three African farmers) because of the high fixed and working capital required, and the large area of suitable soil needed for rotations.Footnote 107 Confronted with the high cost of production, poverty, lack of credit facilities, tobacco curing barns, and technical assistance, Africans could not venture into production of flue-cured Virginia tobacco, and instead grew lower value tobaccos such as Turkish and Burley.

The Turkish tobacco scheme was a colonial initiative to harness cash crop production despite ecological marginalisation and land scarcity in African areas. The Turkish crop could thrive in the drier parts of the country with poor sandy soils, into which Africans had been forced by racist land segregation policies. Turkish tobacco was also ecologically ideal for the African farmer in the Native Reserves, as it did not denude natural resources like woodlands and did not require firewood for curing like flue-cured Virginia.Footnote 108 Officials also felt that Turkish tobacco fit within the NLHA template of soil conservation and cash crop production.Footnote 109 Experiments growing Turkish tobacco on overworked and poor soils in rotation with other crops such as maize, sunn hemp, and rapoko, in an effort to improve soil fertility, were initiated by the Department of Native Agriculture in the Native Reserves (later called Tribal Trust Lands, or TTLs, when the NLHA was repealed in 1962) of Chinhamhora.Footnote 110 In 1956, production extended to other native reserves. During the 1959–60 season, out of a total Turkish harvest of 1,878,000 lbs in Southern Rhodesia, 618,000 lbs were produced by 4,444 African growers.Footnote 111 By 1958, production by Africans spanned 150 acres.Footnote 112 Between 1957 and 1960, the average gross output value from Turkish tobacco ranged from £38.12s per acre to £58.12s.11d. per acre, a figure between five and six times the yield of low unit value crops in the African areas.Footnote 113 However, the adoption of Turkish tobacco production amongst African farmers was slowed by high transportation costs, high labour costs, and limited capital investments for farm expansion, all of which made the crop too costly to grow.Footnote 114 In the end, Turkish tobacco production by African peasants remained marginal in the 1950s.

Turkish tobacco production generated class differentiation amongst peasants as some accumulated capital and investments that altered the agricultural landscape in African areas. This was most conspicuous in the NPAs and, particularly, in Musengezi NPA, which became one of the ‘most progressive farming areas in the country’.Footnote 115 By 1965, 53 farms in Musengezi NPA were fully fenced and subdivided into paddocks enclosing 18,000 acres of rotational grazing.Footnote 116 These developments on African farms were now possible as the average income of each NPA farmer from tobacco was estimated to be around £300–400 gross, with a few individuals earning £1,000 or more. One of the model African farmers, Mr Griston Mungofa, practiced intensive farming, putting under twenty acres of tobacco and twenty acres of maize a year while practising rotation to integrate grazing.Footnote 117

The income and class differentiation precipitated by Turkish tobacco in the NPAs prompted the state to integrate the crop within its new native administration outlook during the 1960s, as it abandoned the coercive approach of high modernism in pursuit of the much more integrative policy of community development.Footnote 118 Community development was predicated on the integration of African systems into colonial administration and encouraging Africans to stay on the land at a time of simmering nationalism and rampant urban protest. Expanding cash crop production to TTLs and raising rural incomes could forestall rural political discontent.Footnote 119 Thus, from the 1960s, the state expanded the Turkish tobacco endeavour to most poor and dry TTLs in Fort Victoria province (Gutu, Zimuto, and Bikita TTLs), the Midlands, and Manicaland provinces. African Turkish tobacco farmers were given seedlings from the African Loan Fund, set up in 1958 to grant loans to peasants.Footnote 120 Technical assistance was deployed using state-trained tobacco officers to help and encourage participation and cooperation of peasants in arable conservation, maintenance of contours, soil fertility, and grazing management.Footnote 121

However, despite this, the gross returns in most of the TTLs were poor, amounting to a mere £5 per acre, while production costs hovered around £18 to £20 per acre.Footnote 122 The poor remuneration saw the acreage planted fall drastically between the 1967–8 and 1968–9 seasons, from 1,100 to 213 acres, respectively. Reservations began to be expressed on the commercial value of the enterprise particularly in the poor sand soils of the TTLs. The Secretary for Internal Affairs pointed out that the extremely low profit margins of the crop in the TTLs made it impossible to continue with government support. In fact, he recommended the abandonment of the project:

It seems to me that with the possible exception of very few Purchase Area Farmers who may be making something out of the crop. There is no attraction in the crop at the present price of 25d. . . . In the circumstances I must support the recommendation that government support for the crop be dropped.Footnote 123

When the state decided to withdraw support for the Turkish tobacco production, new entities emerged to fill the void. The Tribal Trust Lands Development Cooperation (TTLDCOR), formed in 1968 to develop TTLs with European private capital, stepped in underwrite the production of 150,000 lbs to 200,000 lbs of Turkish tobacco during the 1969–70 season and ensuing years. This was a result of a steady increase in local consumer demand for the Turkish tobacco used in toasted cigarette brands, such as Gunston and Texas.Footnote 124 As a result, Turkish tobacco prices rose from under R$1 to R$1.35 (Rhodesian dollars) per kilogram over three years beginning in 1974.Footnote 125 The rise in prices nevertheless failed to raise production of Turkish tobacco in African areas, as acreages under cultivation decreased. In Victoria district, the number of growers had declined because of lack of watering facilities for seedlings and poor financial returns from the crop.Footnote 126 In the Midlands, Turkish tobacco was overtaken by cotton.Footnote 127 The Turkish tobacco interim survey of 1975 concluded that under the prevailing standards of management, tobacco production in the TTLs was not sufficiently profitable to encourage significant further expansion.Footnote 128 The survey noted that the only way yields — and concomitantly profits — could be raised would be through an effective extension system and field management involving fumigation, adequate pest control, and fertilisation of soils.Footnote 129

The collapse of commercialised production of Turkish tobacco within the TTLs created new opportunities for cultivation by women. From 1975, there was an interesting shift in the gender of the farmers — as much of the tobacco farming was now being done by women, or so-called ‘farmers’ wives’ — in their backyards.Footnote 130 This was possible because the processes of Turkish cultivation such as reaping, curing, and cultivation required less physical strength and were therefore deemed more suited to women and children.Footnote 131 However, the district commissionerFootnote 132 of Inyanga noted that these women growers could not even be qualified as real tobacco growers because they did not see the crop as a cash crop, but just as a trivial effort to make ‘pocket money’.Footnote 133

Tobacco production: a model for conservation and development in African areas or a political tool?

The African Turkish tobacco initiative in Southern Rhodesia reveals how crop hierarchies — a pyramid based not only on economic rationale but on the political ideology of control — helped institutionalise patterns of white settler dominance in the countryside and agrarian economy. White settler cash crop hegemonic ideologies shaped colonial development paradigms in African areas and the nature of African participation in the agricultural economy. Even within the new colonial development narratives of modernisation and technical intervention during the late 1940s and 1950s, African cash crop production remained pigeon-holed within the hegemonic imperatives of servicing white settler interests and agricultural export growth for administrative and political expediency. Predictably, the Turkish tobacco drive failed to have a significant positive impact on improving the physical environment and African accumulation patterns — with limited success in the NPAs and less still in the TTLs. This was because postwar policy intervention in the rural areas had a much broader political objective than the much-touted modernist and technical rationale of transforming African export agriculture through encouraging cash crop production. The rise of nationalism and the tide of decolonisation imperilled most settler colonies and threatened the status quo of white farmers in the countryside, precipitating the need for rural reforms. Within this context, it is important to note that the crop hegemonic status quo that had hitherto impinged on African peasants and the structural constraints to their participation in the global export production were not dismantled but, instead, shifted to accommodate new colonial priorities and new idioms of control and authority. Notably, the postwar imperial project of encouraging cash crop production by African peasants was foisted upon a settler state that implemented piecemeal rural reforms. These reforms were not intended to create a real rural bourgeoisie, but rather a quiescent class of African farmers who might serve as a political buffer. The overwhelming logic was to construct a Black farmer with a stake in the political economy and make him an ally against subversive rural elements.Footnote 134 In the end, the state's drive to encourage African cultivation of Turkish tobacco was part of a political project to impose political control and extend colonial authority in a way that could not lead to the emergence of a strong African agrarian bourgeoisie to disrupt white settler farmer privilege.Footnote 135 Tobacco was still, therefore, a hegemonic crop, as its cultivation was used to control patterns of accumulation in African areas in ways that could contain rural discontent and preserve white settler dominance. While tobacco was a high value crop which transformed rural livelihoods and created a strong agricultural middle class in Latin America, the colonial state to preclude the same from happening for Africans in Southern Rhodesia. The cultivation of tobacco was limited to a containment strategy for threats to rural stability. During the late 1970s, at the height of the War of Liberation, the Rhodesian state conscripted African farmers to grow Burley tobacco in abandoned white farms under the guise of combating land denudation and soil erosion as well as raising rural incomes.Footnote 136 However, this measure was part of a broader counter-insurgency strategy to create buffer zones against guerrilla incursions as vacant farms were becoming breeding grounds for African nationalist fighters and tobacco farms were seen as the first line of defence.Footnote 137 The enduring objective and design of state policy on tobacco production remained to relegate African producers to second-class farmers in a white-dominated tobacco farming sector, producing those low-profit tobacco types unwanted by white farmers and sustaining the domestic demands for Turkish tobacco.

In the long run, the colonial project failed at tackling the glaring problems of the African rural economy such as lack of capital, poor soils, and inability to invest in technical services and infrastructure. This became more conspicuous in the years after the Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI) in 1965, as state expenditure for African agriculture fell from 2.8 per cent of total spending between 1966 and 1969 to a mere 1.2 per cent in the years 1975 to 1976.Footnote 138 The economic sanctions imposed by the United Kingdom on Rhodesia in 1966, in response to the UDI, severely crippled white settler agriculture and hit tobacco farming hardest. Tobacco export receipts dwindled by a massive 82 per cent from 93.9 million to 16.7 million Rhodesian dollars between 1965 and 1966.Footnote 139 The state had to intervene with the tobacco support program to subsidise white tobacco farmers, with this assistance amounting to 22 million Rhodesian dollars in 1970. Thus, much of the state funding for African agriculture was withdrawn in order to subsidise white farmers during the UDI.Footnote 140 This affected African Turkish production as government technical support went down, amid falling tobacco prices induced by the tobacco embargo. Bereft of subsidies (unlike white tobacco farmers), and confronted by a drastic cut in funding, African Turkish tobacco farmers were unable to remain competitive producers and their enterprises inevitably collapsed. This case was different to Kenya where African coffee producers were relatively more successful and even outcompeted European growers. This was because unlike in Southern Rhodesia, the colonial state in Kenya was obliged to sacrifice incompetent European producers to support competitive African farmers to ensure the survival of the coffee export sector.Footnote 141 In Kenya, the state actually reduced its financial assistance to white farmers and, when coffee prices plummeted, settler farmers could not compete with low cost African cultivators.Footnote 142 The role of ‘off-farm incomes’ in the success of rural cash cropping in colonial Africa has also been emphasised by Mary Tiffen, Francis Gichuki, and Michael Mortimore in their work on Kenya.Footnote 143 In Southern Rhodesia, restrictions on black urban employment meant that there was limited off-farm investments to supplement meagre capital resources from cash-cropping.Footnote 144

Indeed, there were very few African farmers who were success stories in these state programs — mostly those in the NPAs with access to relatively better land and capital opportunities.Footnote 145 Amongst African farmers state initiatives did little to stimulate positive change in the environmental and economic landscapes. State financial assistance was very little, African plots too small, and the soils so poor that tobacco cultivation accelerated erosion.Footnote 146 A state agricultural official highlighted in 1978 that the efforts made in the TTLs had not succeeded in raising the standard of living for the so-called ‘tribesman’, or in slowing down the rate of deterioration in the country's natural resources.Footnote 147 Even the state's own Five Year Plan in 1979 admitted that land pressure in most TTLs caused livelihood insecurity and poverty amongst Africans and was destroying the land.Footnote 148

In the final analysis, peasant agency and autonomy in tobacco production by Africans in Southern Rhodesia was severely limited by the state and white growers, so that there was never a truly independent peasant producer class during the colonial period. Even during episodes of so-called booms in rural commodity production, the pervasive precarity of African peasant economies was evident in their subordination to larger forces such as the interests of settler agrarian capitalism and global commodity market dynamics. Within this colonial leviathan, the agency of the peasant tobacco producers was hamstrung by the broader colonial objectives: to maintain labour supplies, create a domestic market for settler tobaccos, and preserve security in the countryside through piecemeal encouragement of cash crop production and guided rural accumulation. Thus, the hegemonic value of tobacco as an important export crop for white settler power and survival in Southern Rhodesia constructed the narrow and constricted ‘tight corners’ within which peasant agency and autonomy was negotiated and navigated under shifting structural factors. While there were complex variables at play like global market forces, political contexts, and social demographics, the constant was the hegemonic imperative to control and curtail African participation in the export economy. The aim was to confine Africans to modes of agrarian development amenable to coercive political and economic control without disrupting the hegemonic centres of white power.

Conclusion

African tobacco production in Southern Rhodesia, just like colonial peasant production elsewhere, must be understood within the context of shifting colonial state priorities constructed around power relations revolving around commodity production, the global export forces, and the changing dynamics of the commodity value chain. The hierarchy of commodities was instrumentalised in various ways to control African peasantries depending on the changing patterns of global economic and political pressures. But eventually, it was the colonial state that structured not only factors of production, but also relations of production amongst producers on the land. And the imperative to prop up settler capital always defined the state's response to peasant production.

We have joined the debate on the impact of colonial state policy on African peasant producers. We have argued that while there was certainly evidence of peasant initiative in circumnavigating the restrictive colonial regulations, as much recent scholarship has shown, it is imperative to move beyond agency and locate other centres of historical change in colonial peasantries, which involve subtle but important political processes constructed over international commodity networks, local economic processes, and power relations. These of course were not stagnant but shifted over time. They evoked colonial revisionist programmatic interventions in African agriculture, but essentially the colonial project on African peasantries was to create a malleable and tractable class of African producers. We have contended that each crop and agricultural commodity produced by Africans had a unique colonial encounter and context. These encounters and contexts were shaped by how colonialists viewed the crops themselves, their value to the basis of white settler economic power, and how native cultivation of such crops would impinge on and challenge that power and, with it, the whole institution of colonial hegemony. Tobacco in Southern Rhodesia was thus a hegemonic crop, solidifying the precincts of white economic dominance and, for that reason, African production had to be more significantly curtailed than in other commodities, like maize, beef, small grains, and cotton. Even when the state encouraged such production, as from 1952 to 1980, it was with the condescending benevolence that only allowed Africans to cultivate the ‘inferior tobaccos’, while flue-cured tobacco remained a preserve of Europeans until independence. Finally, we argue that the value of a specific crop in the hierarchy of power hegemonies in the colonial state determined the extent and level of peasant curtailment, control, and decline. Thus, while agency has palpable conceptual utility in colonial African peasant studies, moving beyond it to engage power asymmetries and disparities amongst agricultural commodities within the colonial economy affords a new understanding of the pervasive and enduring constraints of white settler power on peasant autonomy and independence.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the reviewers and editors of The Journal of African History.