No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

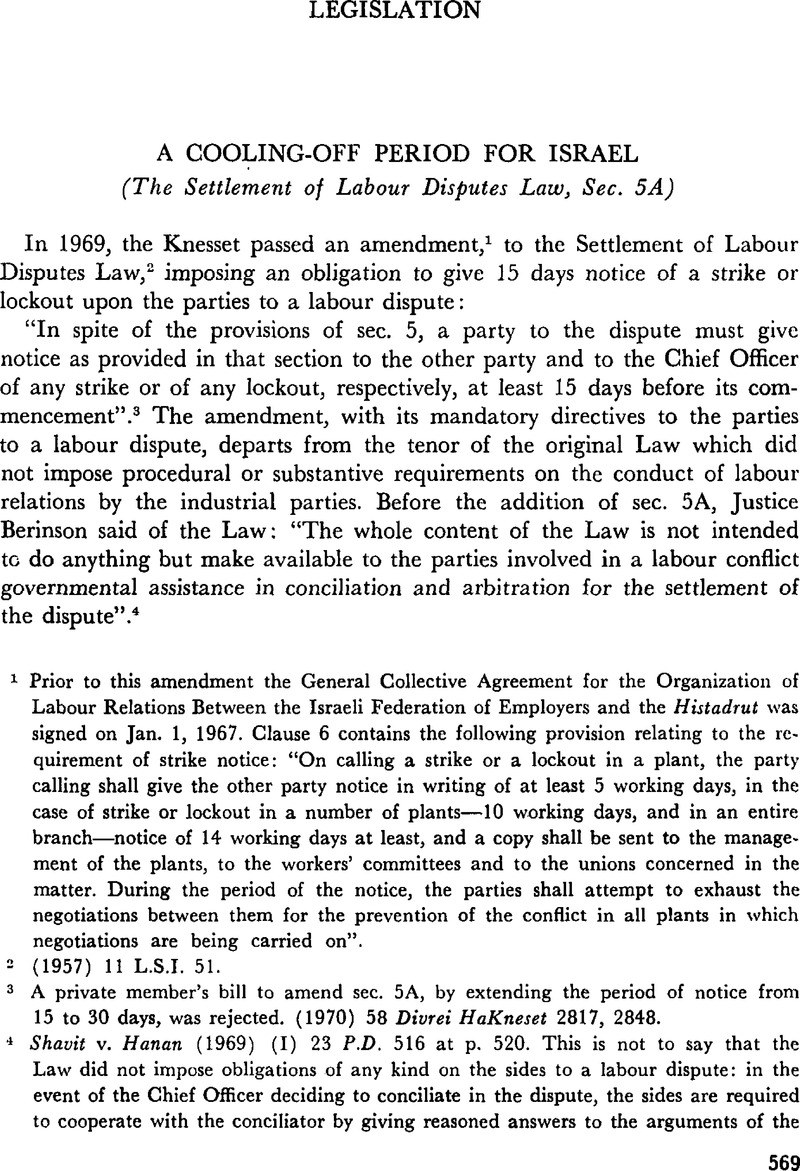

A Cooling-off Period for Israel

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 12 February 2016

Abstract

- Type

- Legislation

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Cambridge University Press and The Faculty of Law, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem 1971

References

1 Prior to this amendment the General Collective Agreement for the Organization of Labour Relations Between the Israeli Federation of Employers and the Histadrut was signed on Jan. 1, 1967. Clause 6 contains the following provision relating to the re quirement of strike notice: “On calling a strike or a lockout in a plant, the party calling shall give the other party notice in writing of at least 5 working days, in the case of strike or lockout in a number of plants—10 working days, and in an entire branch—notice of 14 working days at least, and a copy shall be sent to the management of the plants, to the workers' committees and to the unions concerned in the matter. During the period of the notice, the parties shall attempt to exhaust the negotiations between them for the prevention of the conflict in all plants in which negotiations are being carried on”.

2 (1957) 11 L.S.I. 51.

3 A private member's bill to amend sec. 5A, by extending the period of notice from 15 to 30 days, was rejected. (1970) 58 Divrei HaKneset 2817, 2848.

4 Shavit v. Hanan (1969) (I) 23 P.D. 516 at p. 520. This is not to say that the Law did not impose obligations of any kind on the sides to a labour dispute: in the event of the Chief Officer deciding to conciliate in the dispute, the sides are required to cooperate with the conciliator by giving reasoned answers to the arguments of the other side and to proposals for settlement of the dispute. Settlement of Labour Disputes Law, sees. 7, 8.

5 Sec. 5B.

6 (1968) 53 Divrei HaKnesset 712 (per I. Kargman); (1969) 55 Divrei HaKnesset, 3815, per M. Arom.

7 (1968) 53 Divrei HaKnesset, 710, 712, 714, 718, 727; (1969) 55 Divrei HaKnesset, 3815, 3819, 3821.

8 Keevil & Roose v. A.G. (1943) S.C.D.C. 253.

9 See especially Eshed v. State of Israel (1954) 16 P.E. 100.

10 Ibid., at 125, per Goitein J.

11 The Civil Wrongs Ordinance (New Version) sec. 1 (1968) 10 New Versions 266; sec. 63 originated in sec. 6 Civil Wrongs Amendment Ordinance (1947) Suppl. I. Palestine Gazette 42. (Sec. 55A of the original Ordinance). Adama International Company in Israel v. Lydia Levy (1956) 10 P.D. 1666.

12 See supra n. 6; the explanatory note in the Bill does not refer to the problem of enforceability of the section. (1968) 19 Hatza'ot Hok 22.

13 (1968) 53 Divrei HaKnesset, 727.

14 (1969) 55 Divrei HaKnesset, 3815.

15 Ibid., 3821.

16 Salmond on Jurisprudence, ed. by Fitzgerald, (Sweet and Maxwell, 12th ed., 1966) 140Google Scholar; See also Craies on Statute Law, ed. by Edgar, (Sweet & Maxwell, 6th ed., 1963) 128–130.Google Scholar

17 Tedeschi, , Englard, , Barak, , Cheshin, , The Law of Torts: General Part (Magnes Press, Jerusalem, 1969) per Cheshin 53, 54Google Scholar; Yadin, , “On the Interpretation of Laws of the Knesset” (1970) 26 HaPraklit 358, at p. 358.Google Scholar The legitimacy of using travaux préparatories in statutory interpretation has been upheld by Sussmann, J. (1962) 16 P.D. 2467 and see especially at p. 2479Google Scholar; (1965) (II) 19 P.D. 57; (1966) (I) 20 P.D. 401; (1966) (IV) 20 P.D. 253: by Berinson, J. (1962) 16 P.D. 981Google Scholar; and by Silberg, J. (1968) (I) 22 P.D. 618.Google Scholar For the opposing view, see Cohn, J. (1965) (II) 19 P.D. 369Google Scholar; (1966) (I) 20 P.D. 401; (1967) (II) 21 P.D. 325.

18 Under sec. 63, as will be seen below, the plaintiff in an action for breach of statutory duty need only show that the Law intended to bestow a benefit or protection upon him; the defendant may then rebut the claim to a remedy by showing that “on a proper construction of such law, the intention thereof was to exclude such remedy”. [Italics by the author].

19 District Labour Court, Beersheva, File No. LA/1–4, 8.10.1970. Not published.

20 (1971) 25 P.D. 129.

21 See District Court File No. 41/77 for record of the details of the interlocutory injunction.

22 Ibid.

23 See supra n. 20 at 131.

24 Tedeschi et al., op. cit., per Cheshin 104–111.

25 Kassem v. Nazareth Municipal Council (1956) 10 P.D. 243, at p. 249; Frou Frou Biscuits Ltd. v. Froumine & Sons Ltd. (1969) (II) 23 P.D. 43, at p. 47. The function of New Version Laws is consolidation of existing laws and though the structure of sec. 55A of the original Ordinance has been altered in sec. 63 of the New Version, neither its language nor its meaning have been changed. Throughout this article, wherever mention of sec. 55A has been made in quotations from articles, books or judgments, it has been altered to sec. 63 to avoid confusion.

26 Winfield on Tort, ed. by Jolowicz, and Lewis, (Sweet and Maxwell, 8th ed., 1967) 130.Google Scholar See Fricke, , “The Juridical Nature of the Action upon the Statute” (1960) 76 L.Q.R. 240.Google Scholar

27 Monk v. Warbey [1935] 1 K.B. 74 at p. 81.

28 Doe v. Bridges (1831) 1 B & Ad. at p. 859.

29 (1854) 3 E & B 402.

30 Sereg Adin Ltd. v. Mayor of Tel Aviv & Yaffo, (1957) 11 P.D. 1110, pp. 1115–6. See also Shachada v. Hilu (1966) (IV) 20 P.D. 617, at p. 620; Jadoon v. Slyman (1959) 13 P.D. 916, where the transferred burden of proof appears to have been a material ground for the decision.

31 Atkinson v. Newcastle Waterworks Co. (1877) 3 Ex.D. 441.

32 See above, the test in Monk v. Warbey.

33 See Shachada v. Hilu, loc. cit., per Landau J.

34 It is clear that “a part of a piece of legislation” may be held to give grounds for an action in breach of statutory duty even where the piece of legislation as a whole is not intended to be for the benefit or protection of any person: see Mandel (née Vishenstern) v. Municipality of Petah Tikva (1965) 19 P.D. 541, 545.

35 Prizker v. Friedman (1953) (IV) 7 P.D. 674 at pp. 688–90. Silberg J. further explained his holding in this case in Kassem v. Nazareth Municipal Council, loc. cit., by saying that “persons generally” in sec. 55A did not mean the general public since its geometrical position, half way between a single person and a class of persons showed that it was intended to be a concept between these two concepts, as for example workers on a particular kind of machine.

36 Sereg Adin Ltd. v. Mayor of Tel Aviv and Yaffo, loc. cit., at pp. 116–117; Shachada v. Hilu, loc. cit., at p. 621.

37 It could be claimed that a party to a labour dispute has an interest in the Chief Officer's intervention in the dispute for the purposes of conciliation and that, therefore, breach of a duty to give notice to the Chief Officer gives a cause of action to that party under sec. 63. The objection to such a claim is that, even if the Chief Officer is informed of a labour dispute, his intervention is a discretionary power; thus it seems highly unlikely that the Settlement of Labour Disputes Law could be interpreted as being intended for the benefit or protection of the parties to the dispute in so far as the conciliation services of the Chief Officer are concerned. Sec. 6 of the Law reads: “where a notice under secs. 5 or 5A has been delivered or the Chief Officer has learnt of a labour dispute in any other manner, the Chief Officer shall decide whether he will conciliate in the dispute…” Even were sec. 5A to be interpreted as giving an interest in the Chief Officer's conciliation to the parties to a labour dispute, it should be considered impossible for the parties to show damages, as they are required to do in an action under sec. 63, since proof of damage would rest upon a series of hypotheses and not upon a chain of causation.

38 (1968) 19 Hatza'ot Hok 220; the change in the proposed amendment probably originated with a suggestion by Becker, M. K. during the 1st reading, (1968) 53 Divrei HaKnesset 721.Google Scholar

39 Balkis Consolidated Co. v. Tomkinson [1893] A.C. 396. The duty in this case was the duty to register shareholders on the company's register.

40 [1921] 1 K.B. 616.

41 See supra n. 34.

42 It has been held, with relation to sec. 63, that the injured plaintiff need not show financial damages: Jadoon v. Slyman, loc. cit., 923; Liebowitch and Matalon & Sons Ltd. v. Katz (1964) 18 P.D. 384 at pp. 393–4. Re damage caused by loss of opportunity to make preparation, see Mantel v. Municipality of Petah Tikva, loc. cit.

43 See supra n. 37.

44 Street on Torts (Butterworths, 4th ed., 1968), p. 278; See Ashby v. White (1703) 2 Ld. Raym. 938; Ferguson v. Earl Kinnaull (1842) 9 Cl. & Fin. 251.

45 See supra n. 40 at 631.

46 There is some authority for the proposition that the power to give nominal damages has been bestowed upon Israeli courts by sources extraneous to the Civil Wrongs Ordinance. The theories upon which this proposition is founded are, however, subject to doubt. See Tedeschi et al., op. cit., per Barak 575–8. If nominal damages can be given in Israeli Law, it seems that they may be given in relation to sec. 63: Ibid., p. 175 per Englard, p. 578 per Barak.

47 For the availability of a defence of constructive notice see Mantel's case, loc. cit., at 545, per Landau J. The availability of a defence of constructive notice in relation to sec. 5A is of some importance since in practical terms, it would probably mean that notice to the Chief Officer would deprive the other party to the labour dispute of a cause of action under sec. 63, since it is likely that the Chief Officer would, in dealing with the notification, approach the other party to the dispute, thus conveying the knowledge of the approaching strike or lockout.

48 The Civil Wrongs Ordinance (New Version) sec. 1 (1968) 10 New Versions 266. But see also the discussion of the Divrei HaKnesset above and the Israeli authorities relating to their utilization in statutory interpretation.

48 Street on Torts 275.

50 Square v. Model Farm Dairies Ltd. [1939] 2 K.B. 365; Street, op. cit., 271, 275.

51 Kassem v. Nazareth Municipal Council, loc. cit., at 250; Jadoon v. Slyman, loc. cit., 923; Liebowitch and Matalon & Sons v. Katz, loc. cit., at 394.

52 Wheeler v. New Merton Board Bills Ltd. [1933] 2 K.B. 569.

53 Street on Torts, 280.

54 (1956) 10 P.D. 1666. This wider approach to tortious liability outside the frame-work of the Civil Wrongs Ordinance has been a subject of fierce controversy. Berinson J. in further explaining his dicta, said that the Ordinance did not exclude other torts and that it could not block the channel of reception of English common law torts through art. 46 of the Palestine Order-in-Council: Jadoon v. Slyman, loc. cit., at 924. For a supporting view, see Tedeschi, , “Bodily Injuries without Use of Force and ‘Wilful Negligence’” (1967) 23 HaPraklit 170, at 185.Google Scholar The Adama dicta was rejected in Vider v. A-G (1954) 10 P.D. 1246, at 1248–9, in which it was held that the Civil Wrongs Ordinance contained a numerus clausus of civil wrongs and there could be no resort to English common law to find torts not included within it. Berinson J. himself acknowledged in a recent case that the weight of authority denied the existence of torts outside the Civil Wrongs Ordinance and he intimated that he was now prepared to abide by the majority view: Esperanta Natan v. Abdulla (1970) (I) 24 P.D. 455 at 462.

55 Ibid., at 1672.

56 Tedeschi et al., op. cit., per Cheshin 106.

57 Ibid., 106–107, per Cheshin.

58 See supra n. 54.

59 Jadoon v. Slyman, loc. cit., at 921.

60 Loc. cit., at 924.

61 Tedeschi et al., op. cit., per Cheshin 111.

62 Cheshire, and Fifoot, , The Law of Contract (Butterworth, 7th. ed., 1969) 139–156.Google Scholar

63 Zeltner, , Contracts, Vol. II (Tel Aviv, 1965), 338.Google Scholar

64 See secs. 12, 13, 14.

65 Zeltner, op. cit., at p. 339.

66 Although there are isolated examples of cogent law enforced as implied contractual terms e.g., The English Housing Act, 1957, sec. 6.

67 Sec. 3. For the language of this section, see text at n. 70.

68 (1957), 11 L.S.I. 58.

69 Secs. 25–33 inclusive.

70 It should be noted that sec. 5A cannot be implied as a term in an employment contract because sec. 3 of the Settlement of Labour Disputes Law defines the parties to a labour dispute in such a way as to clearly exclude the individual employee as a party to a labour dispute. Even if sec. 5A were an implied term of a collective agreement, it is improbable, in view of the definition of party to a labour dispute, that it could be considered a personal obligation under sec. 19 of the Collective Agreements Law and hence be implied indirectly into the employment contract.

71 Even if there are difficulties in determining on whom the legislature intended the duty to be imposed, this will not give grounds for rejecting an action in breach of statutory duty; see Simmonds v. Newport Abercarn Black Vein Steam Coal Co., supra p. 580.

72 The difficulties of determining which employees are affected by any specific labour dispute is a recognized problem in sociological studies. See, for example, Chamberlain, and Schilling, , The Impact of Strikes—their Social and Economic Costs (1954)Google Scholar; Rideount, , “Strikes” (1970) 23 Current Legal Problems 137.CrossRefGoogle Scholar In sec. 10 of the U.K. Ministry of Social Security Act, 1966, “persons affected by trade disputes” are described as being so affected “…where by reason of a stoppage of work due to a trade dispute at his place of employment a person is without employment for any period during which the stoppage continues…”, the purpose of the section is to deprive such persons of benefits and the section does not apply where the person “…is not participating in or financing or directly interested in the trade dispute…; and … does not belong to a grade or class of workers of which, immediately before the commencement of the stoppage, there were members employed at his place of employment any of whom are participating or financing or directly interested in the dispute”.

73 (1958) 12 P.D. 1261.

74 At 1268.

75 At 1271.

76 In French law, from which the Ottoman Law was derived, registration is considered to be a formal requirement and failure to register does not entirely negate the legal personality of a T.U. See Verdier, J. M., Traité de Droit du Travail, Syndicats (Paris, Dalloz, 1966), pp. 182–183.Google Scholar

77 The action brought against them should be by way of representative action: Sussmann, , Civil Procedure (Avuca Press, Tel Aviv, 3rd ed. 1967) 81Google Scholar, 83, Cf. The State of Israel and others v. National Union of Radiologists, District Labour Court, Tel Aviv File No. 4.2.69, not published, where Goldberg J. gave an injunction against the defendants although they claimed that they had no legal personality; he held that the Union was stopped from claiming that it had no legal personality because it signed a collective agreement. It is an open question whether one representative elected by the employees could be considered a parry to a labour dispute under sec. 3.

78 Royal Commission on T.U.'s and Employers' Association, Cmnd. 3623, 1965–1968, at p. 123.

79 See e.g. Timna Copper Mines Co. v. Workers Council of Eilat, loc. cit.; State of Israel and Others v. National Union of Radiologists, loc. cit.; Shavit v. Hanan, loc. cit. (where the original employer application for an injunction against the strike was withdrawn).

80 Labour Tribunal Law, 1969, 22 Sefer HaHukim 70; sec. 24(a)(1) of the Law excludes actions arising on the Civil Wrongs Ordinance from the jurisdiction of the Labour Tribunal. See Finstein v. Secondary School Teachers Union. District Court 41/77 (not published).

81 Collective Agreements Law, sec. 24: “Notwithstanding any law, an employees' organization or employers' organization shall not be liable to damages for an infringement of its obligations under a collective agreement save to the extent that it has expressly been made liable thereto by a general collective agreement”.

82 In England, strikes in breach of contract have been said to be unlawful; see Grunfeld, , Modern Trade Union Law, Sweet & Maxwell, (1966) 321–2Google Scholar; Rookes v. Barnard [1964] A.C. 1129; Stratford v. Lindley [1965] A.C. 307. In these cases, the breach of contract was of the individual employment contract and therefore analogous to but not the same as the Israeli situation where the breach will be of a collective agreement. There are no authorities to this effect in Israel.

83 Erensberg v. The Official Receiver (1956) 10 P.D. 121, at p. 125, per Olshan J.: “When relations between employer and employees are decided according to a collective agreement, it is customary to regard a strike of the employees as a lawful strike when it is called with the authorization of the institution or institutions representing the employees, for the purpose of compelling the employer to implement the conditions of the agreement or in order to utilize this tool for the making of an agreement where one does not already exist, or where an existing agreement ceases to be in force. However, I do not think a strike will be regarded as lawful where it is called in order to break an agreement which is in force”. This is not the place to examine the basis or justification for a claim that a strike in breach of contract is unlawful, but it should be noted that the word “unlawful” in this respect is so imprecise as to render it meaningless. If the strike is unlawful does that mean that the employer will be able to claim damages resulting from the strike itself, that employees' social security rights will be cancelled or that the strike will be a criminal offence? Does it mean that employers may obtain an injunction in perpetuum against such a strike, as opposed to an injunction either for 15 days duration or until such time as the intending strikers fulfil the requirements of sec. 5A? None of these results flow directly from a statement that a strike is unlawful and in those statutory provisions which relate to strikes no distinction is drawn between lawful and unlawful strikes.

84 Cohen, Sanford, Labour Law (Charles E. Merrill Books, 1964), p. 346Google Scholar; Knowles, , Strikes (Blackwell, 1954), pp. 37–39Google Scholar; Royal Commission Report, op. cit., pp. 113–114; Tellar, Ludwig, Hearings before the Senate Committee on Education and Labour (80th U.S. Congress, 1st session, 1947) 273.Google Scholar

85 Rehmus, Charles M., “Operation of the National Emergency Provisions of the Labor Management Relations Act of 1947” (1952–1953) 62 Yale L. J. 1047.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

86 Ibid., at p. 1060.