Impact statement

The transition from a mental health system centered on long-term psychiatric hospital care to one centered on community-based services is complex, usually prolonged and requires adequate planning, sustained support and careful intersectoral coordination. The literature documenting and discussing psychiatric Deinstitutionalization (PDI) processes is vast, running across different time periods, regions, socio-political circumstances, and disciplines, and involving diverse models of institutionalization and community-based care. This scoping review maps this literature, identifying barriers and facilitators for PDI processes, developing a categorization that can help researchers and policymakers approach the various sources of complexity involved in this policy process. Based on the review, we propose five key areas of consideration for policymakers involved in PDI efforts: (i) needs assessment, design and scaling up; (ii) financing the transition; (iii) workforce attitudes and development; (iv) PDI implementation and (v) monitoring and quality assurance. We call for a multifaceted transition strategy that includes clear and strong leadership, participation from diverse stakeholders and long-term political and financial commitment. Countries going through the transition and those who are starting the process need a detailed understanding of their specific needs and contextual features at the legal, institutional, and political levels.

Introduction

Starting during and after World War II in Western Europe and North America, psychiatric deinstitutionalization (PDI) is widely considered a central element of the modernization of psychiatry. It involves two broad components: (i) the closure or reduction of large psychiatric hospitals and (ii) the development of comprehensive community-based mental health services aiming to promote social inclusion and full citizenship for people living with severe mental illness A broad international consensus supports the need for a shift in mental health care, away from long-term institutionalization and toward comprehensive and integrated community-based and community-shaped services (Campbell and Burgess, Reference Campbell and Burgess2012; WHO, 2013, 2021a; Thornicroft et al., Reference Thornicroft, Deb and Henderson2016).

Significant economic, social, and cultural forces have precipitated the development of PDI, including public awareness of the dehumanizing effects of prolonged institutionalization in often poor conditions, the high cost of maintaining large, long-stay institutions, and pharmaceutical developments such as the introduction of psychotropic medication (Turner, Reference Turner2004; Yohanna, Reference Yohanna2013; Taylor Salisbury et al., Reference Taylor Salisbury, Killaspy and King2016). For several decades, advocacy movements across the mental health and disability fields have demanded the protection of patients’ human rights, including the right to live independently in the community (Hillman, Reference Hillman2005; Mezzina et al., Reference Mezzina, Rosen, Amering and Javed2019). The UK, Italy, and Finland among other countries are generally regarded as good examples of PDI (Turner, Reference Turner2004; Westman et al., Reference Westman, Gissler and Wahlbeck2012; Barbui et al., Reference Barbui, Papola and Saraceno2018). In the global south, while varying in approach and scale, Brazil, Chile, Sri Lanka and Vietnam have received praise for their efforts to move away from centralized psychiatric institutions (PAHO, Reference Caldas and Cohen2008; Cohen and Minas, Reference Cohen and Minas2017).

Despite the consensus and the declarations by many governments, PDI remains a complex and fragile endeavor. Progress toward PDI varies greatly across and within countries (Hudson, Reference Hudson2019). In some regions, the majority of resources are still invested on centralized, long-term hospitalization (WHO and the Gulbenkian GMHP, 2014); in others, PDI has been delayed with the balance of mental health care shifting in favor of hospital-focused care (Sade et al., Reference Sade, Sashidharan and Silva2021); and in other cases, poor management of the PDI process has resulted in tragedy (see e.g., Moseneke’s, Reference Moseneke2018 account of the Esidimeni tragedy in South Africa).

Understanding the factors that lead to or prevent the transition is crucial to inform the planning and implementation of PDI. Whilst these factors have been documented through the accounts of leaders and experts with hands-on experience, such as in the WHO’s Innovation in Deinstitutionalisation report (WHO and the Gulbenkian GMHP, 2014), there has been no previous attempt to systematically scope the literature on barriers and facilitators to PDI.

This paper therefore reports the results of a Scoping Review examining the extent and range of available research regarding barriers and facilitators involved in PDI processes. We organized the specific barriers in seven groups, and the facilitators in six groups, totaling 13 thematic groups. This categorization can be adapted to national realities and different levels of policy action around PDI, to guide research and policy efforts. The synthesis of this information allows us to establish a list of suggestions on ways to move forward.

Methods

Given that the literature on this topic has not been comprehensively reviewed, the Scoping Review (ScR) (Arksey and O’Malley, Reference Arksey and O’Malley2005) methodology was used. The goal of a ScR is “to map rapidly the key concepts underpinning a research area and the main sources and types of evidence available (…), especially where an area is complex or has not been reviewed comprehensively before” (Mays et al., Reference Mays, Roberts, Popay, Fulop, Allen, Clarke and Black2001, p. 194). For this review, a barrier to PDI was defined as any factor limiting or restricting the transition of care from long-term hospitalization to community-based services and supports. This may include, but is not limited to, issues related to the public-health priority agenda (Shen and Snowden, Reference Shen and Snowden2014); challenges in the implementation of mental health services in community settings (Kormann and Petronko, Reference Kormann and Petronko2004; Saraceno et al., Reference Saraceno, van Ommeren, Batniji, Cohen, Gureje, Mahoney, Sridhar and Underhill2007); the resistance of workers employed by psychiatric institutions (Fakhoury and Priebe, Reference Fakhoury and Priebe2002); and public and community responses, including stigma, paternalism and other sociocultural factors (Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, Haagen and Orkin2005; O’Doherty et al., Reference O’Doherty, Linehan, Tatlow-Golden, Craig, Kerr, Lynch and Staines2016).

Correspondingly, we define a facilitator as any factor that fosters, promotes, or enables an adequate PDI process. These include the presence of well-organized social activism supporting the rights of persons with mental health problems (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Lakin, Mangan and Prouty1998), the acceptance of mental illness as a human condition (Gostin, Reference Gostin2008), service paradigms that enhance social inclusion and citizenship (Fakhoury and Priebe, Reference Fakhoury and Priebe2002; Saraceno, Reference Saraceno2003) and political willingness (Saraceno et al., Reference Saraceno, van Ommeren, Batniji, Cohen, Gureje, Mahoney, Sridhar and Underhill2007).

This ScR was conducted following the Checklist for Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Review (PRISMA-ScR) (Tricco et al., Reference Tricco, Lillie, Zarin, O’Brien, Colquhoun, Levac, Moher, Peters, Horsley, Weeks, Hempel, Akl, Chang, McGowan, Stewart, Hartling, Aldcroft, Wilson, Garritty and Straus2018). A review protocol was created and registered at the Open Science Platform (doi: 10.17605/OSF.IO/XEBQW). See the protocol and PRISMA-ScR Checklist in Supplementary Materials A and B, respectively.

Three electronic databases were searched in May 2020 – Medline, CINAHL and Sociological Abstracts. Previously published systematic reviews on adults with severe mental health impairment (Lean et al., Reference Lean, Fornells-Ambrojo, Milton, Lloyd-Evans, Harrison-Stewart, Yesufu-Udechuku, Kendall and Johnson2019; Richardson et al., Reference Richardson, Richard, Gunter and Derrett2019), barriers and facilitators to healthcare access (Adauy et al., Reference Adauy, Angulo, Sepúlveda, Sanhueza, Becerra and Morales2013) and the deinstitutionalization process (May et al., Reference May, Lombard Vance, Murphy, O’Donovan, Webb, Sheaf, McCallion, Stancliffe, Normand, Smith and McCarron2019) informed our search strategy. The strategy combined terms across three dimensions: (i) adults with mental health impairment; (ii) barriers and facilitators related to health care delivery; and (iii) the deinstitutionalization process. The search strategy was not limited by study design or country. Tailored searches were developed for each database (see Supplementary Material C). Eligibility criteria were limited by studies in English and Spanish. All references obtained through the electronic database search and hand search were pooled in EndNote 11 (reference manager) and then uploaded to Covidence (screening and data extraction tool).

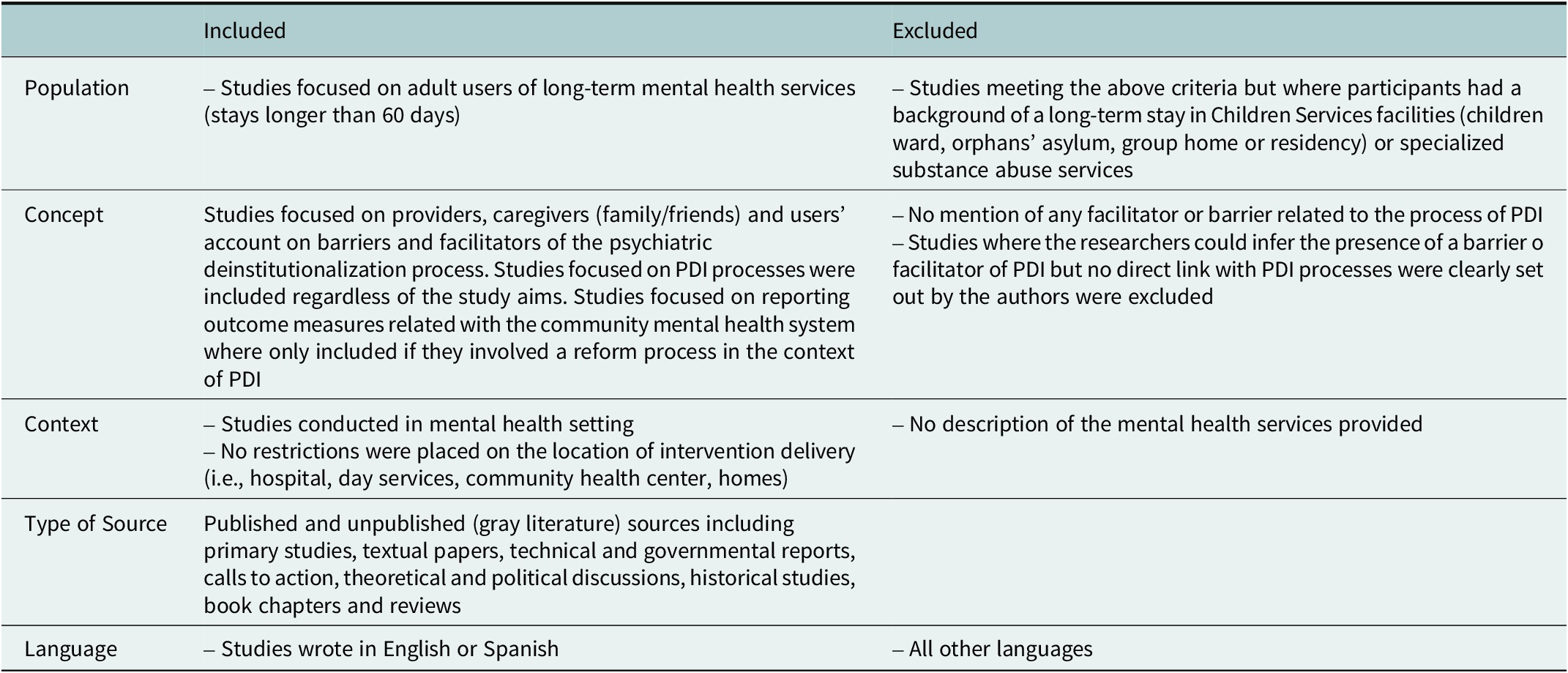

Studies selected for inclusion met the criteria detailed in Table 1. Initial eligibility was independently assessed by JU and JG based on title and abstract. At the level of full-text screening, a random sampling of 10% of the selected studies was pilot-tested (with three reviewers) to ensure at least 80% of agreement. Differences in opinions were discussed, and a final decision on their eligibility was made after discussion with CM. A specific data extraction form was created to record full study details and guide decisions about the relevance of individual studies (Table 2). Two reviewers (J.U.O. and J.G.M.) extracted data and checked for accuracy with another reviewer (C.M.C.). Eligibility criteria were further specified to differentiate and exclude specialized substance abuse services involving the legal system. Studies on child institutionalization and substance abuse were also excluded because of the distinct set of causes and challenges associated with these phenomena. Articles related to transinstitutionalization, the transfer of users from psychiatric hospitals to other institutional settings were excluded unless they addressed PDI barriers and facilitators directly.

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Note: In the light of the potential differences that may affect the process of deinstitutionalization of Mental Health organizations from Social Services and Specialized Substance Abuse Services (like penal law involvement), this kind of interventions will be excluded.

Table 2. Data extraction form

During the research process, inclusion criteria adopted a dimensional character, with studies clearly stating barriers and facilitators on one extreme and studies where they had to be inferred, on the other. Given that ScR methodology is defined as an exploratory strategy to map the state of research on a topic (Arksey and O’Malley, Reference Arksey and O’Malley2005; Peters et al., Reference Peters, Godfrey, Khalil, McInerney, Parker and Soares2015), no attempts were made to assess the methodological quality of the included studies.

Thematic synthesis (Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Harden, Oliver, Sutcliffe, Rees, Brunton and Kavanagh2004; Lucas et al., Reference Lucas, Baird, Arai, Law and Roberts2007; Thomas and Harden, Reference Thomas and Harden2008; Harden, Reference Harden2010) of the selected papers followed a three-stage process. Firstly, it involved free coding the content of the text, to identify barriers and facilitators. Secondly, grouping and organizing the codes into an inductively developed set of categories. Finally, CM examined the categories and their respective codes in the light of the review question to produce an initial set of categories. The match between codes (barriers/facilitators) and categories, and their relevance for the review question was further discussed and refined through rounds of collective revision. A table with examples of the data coding process is available (Supplementary Material D).

To consistently scope the academic production around PDI over several decades, this review includes publications up until May 2020, intentionally excluding the literature related to the Covid-19 pandemic. To properly assess the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic upon processes of Deinstitutionalisation – and on the reality of long-term psychiatric hospitals in general – a different research question, and a tailored design is required.

Results

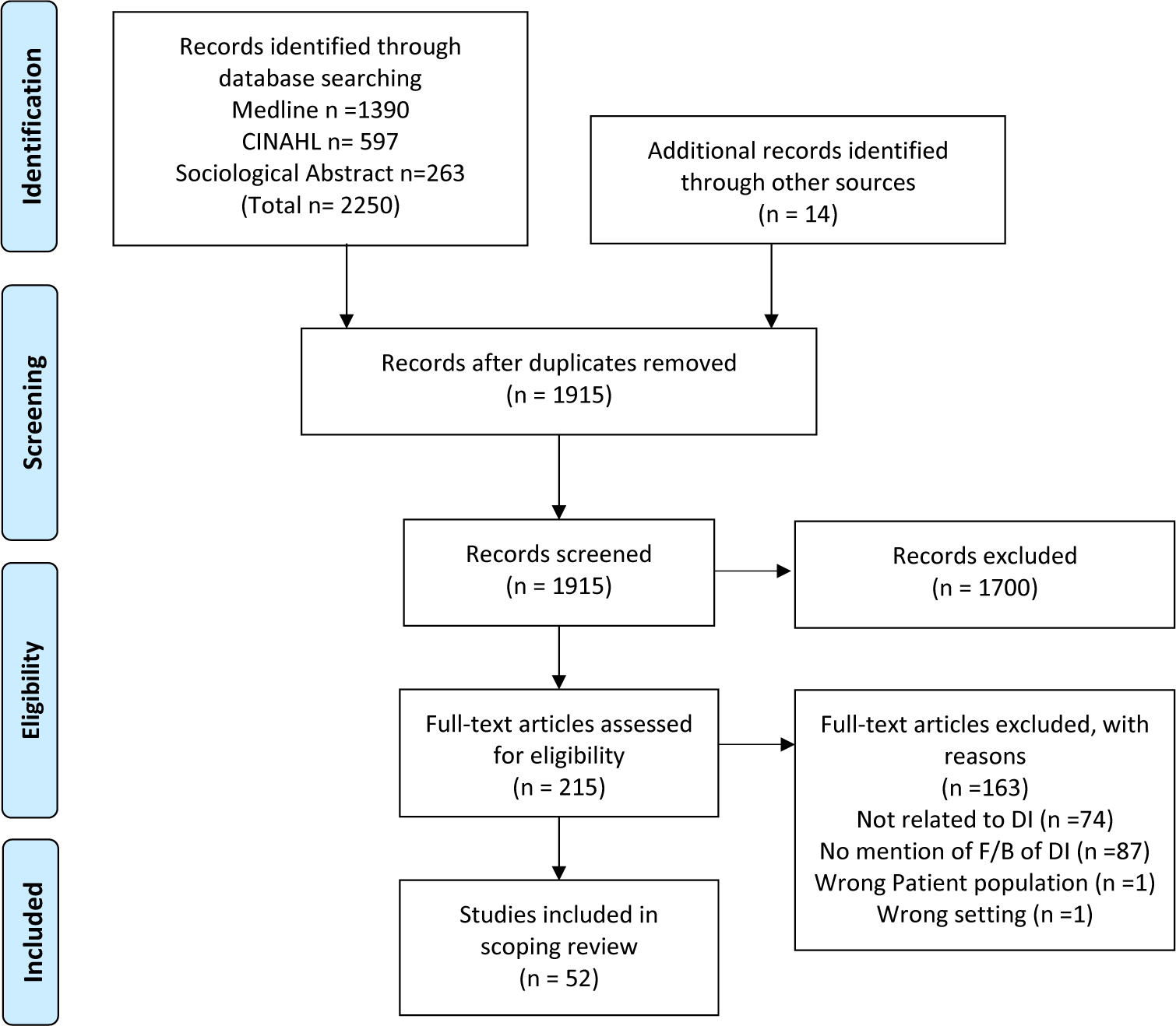

The search strategy retrieved 2,250 references. Nine more references were added after hand-searching reference lists and contacting relevant authors. After duplicate removal, 1,915 references were screened by title and abstract, leaving 215 articles for full-text screening. Finally, 52 studies were included in the analysis. Search results and the reasons for excluding full-text articles are provided in the PRISMA flowchart (Figure 1).

Figure 1. PRISMA 2009 flow diagram.

Characteristics of the studies

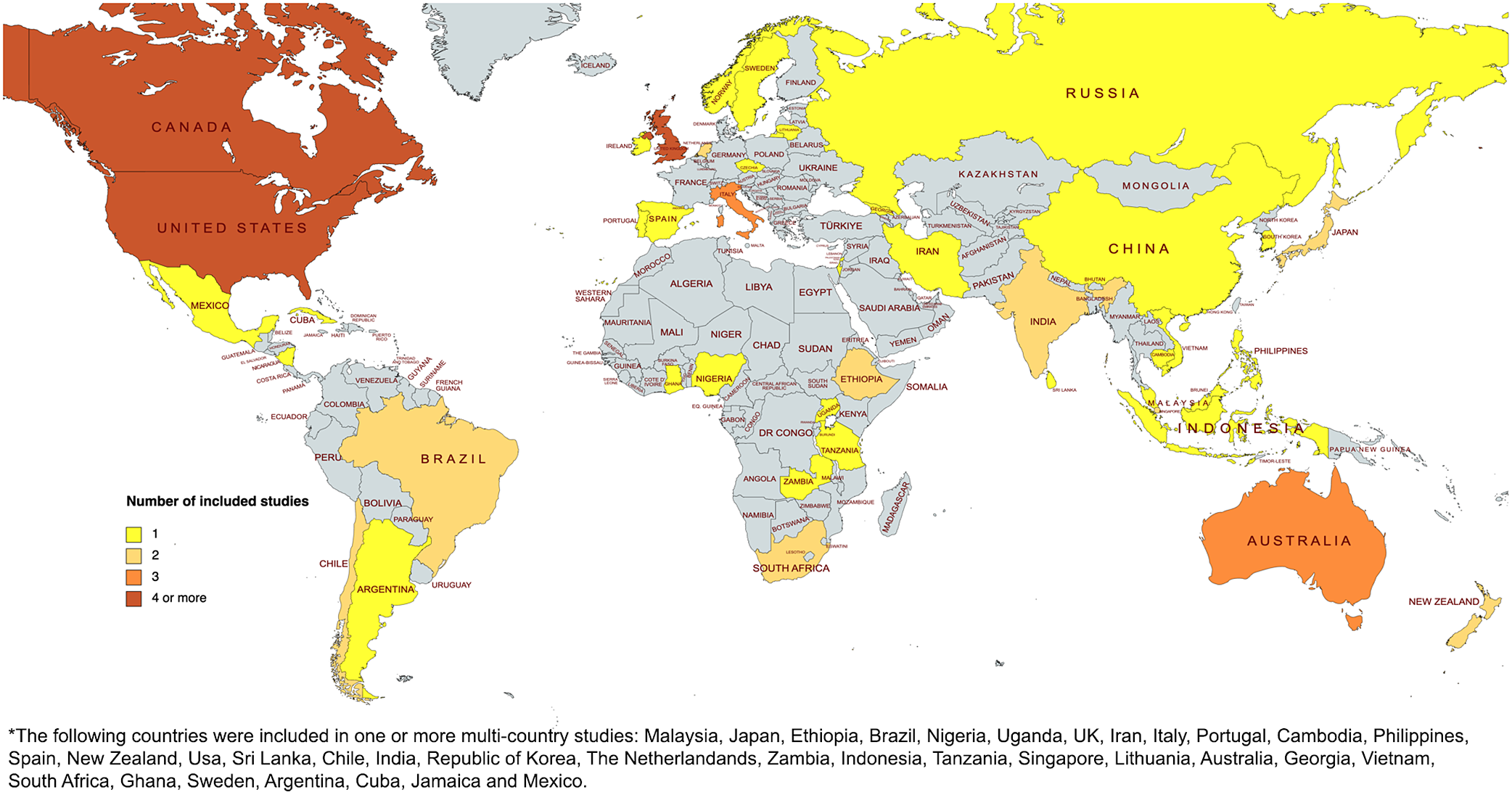

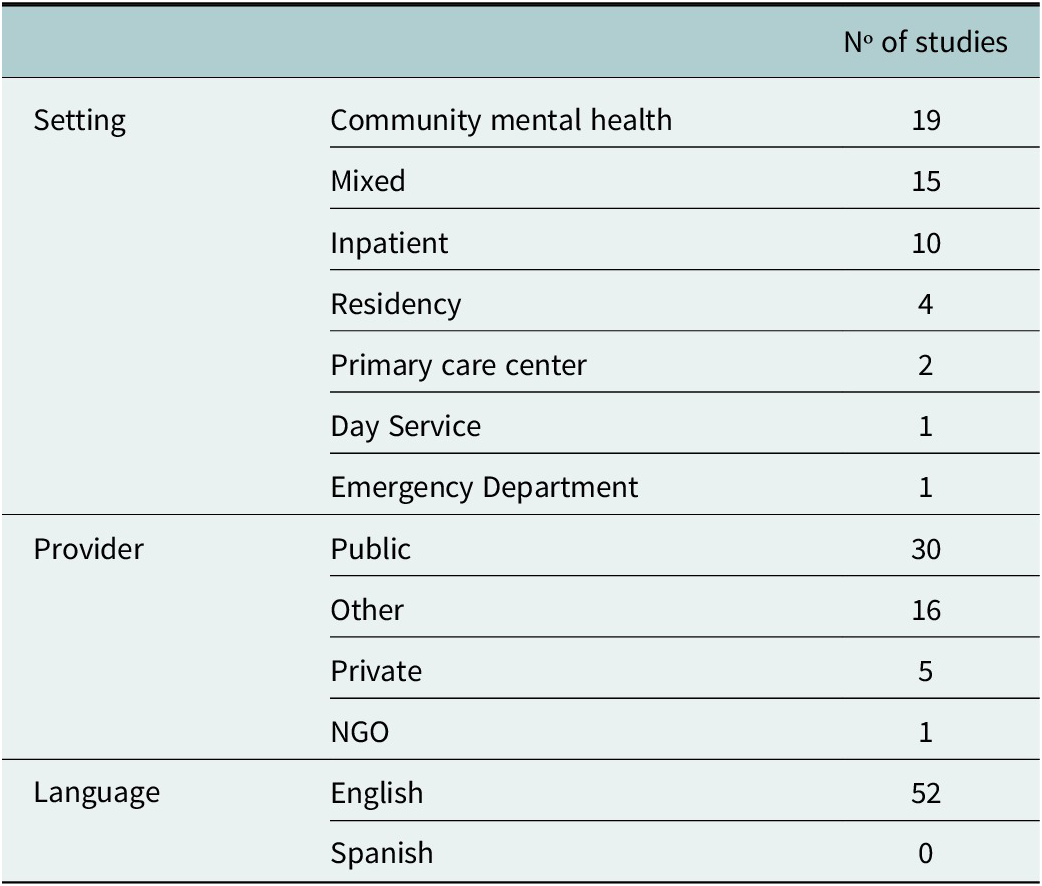

Included studies were published between 1977 and 2019. This broad temporal scope responds to the fact that an important proportion of research was parallel to the implementation of PDI policies in Europe and the USA during the 1970s and 1980s. Studies were predominantly conducted in the USA (n = 22), followed by the UK (n = 7) and Canada (n = 5). Figure 2 shows an overview of the geographical distribution of the included studies. Regarding the methodology, 25 publications were qualitative studies, 22 were quantitative, and 5 used mixed methods. We provide a summary of the studies’ characteristics in Table 3 and descriptions of each study in Table 4.

Figure 2. Geographical distribution of included studies.

Note: The following countries were included in one or more multi-country studies: Malaysia, Japan, Ethiopia, Brazil, Nigeria, Uganda, UK, Iran, Italy, Portugal, Cambodia, Philippines, Spain, New Zealand, USA, Sri Lanka, Chile, India, Republic of Korea, The Netherlands, Zambia, Indonesia, Tanzania, Singapore, Lithuania, Australia, Georgia, Vietnam, South Africa, Ghana, Sweden, Argentina, Cuba, Jamaica and Mexico.

Table 3. Summary characteristics of included studies

Table 4. Study characteristics of included studies

Abbreviations: CMHC, Community Mental Health Centre; ED, Emergency Department.

It is important to consider that this is a general categorization based on the available literature, whose aim is to identify what has been reported as a barrier and as a facilitator in a systematically selected, diverse set of references. We applied thematic analysis to the entire set, and on that basis, we developed this initial categorization. We are not establishing the prevalence of each barrier/facilitator across the set or contrasting the characteristics of each barrier/facilitator across regions or within a specific stage in the PDI process. For specific information about the composition of the categories and codes, see Table 5 for barriers and Table 6 for facilitators.

Table 5. Barriers to the process of psychiatric deinstitutionalization

Table 6. Facilitators to the process of psychiatric deinstitutionalization

Barriers to the process of psychiatric deinstitutionalization

Barriers to the process were organized under seven categories, summarized in Table 5 and described in detail below.

Planning, leadership and funding

This category includes barriers related to design, implementation, monitoring and overall leadership of the process, and its interaction with other policy processes. One barrier is the lack of accountability from the government to carry out the reform properly, refusing responsibility for housing, social or medical needs and not including other agencies in patient discharge planning (Rose, Reference Rose1979). The absence of clear operational goals may hinder performance evaluation (Rosenheck, Reference Rosenheck2000). Charismatic and ideologically driven leadership is important at the beginning, although is vulnerable to political shifts, including elections and changes in government (PAHO, Reference Caldas and Cohen2008).

Barriers related to funding included the lack of a clear policy that assured the reallocation of resources from hospitals to CMHS (Fakhoury and Priebe, Reference Fakhoury and Priebe2002; PAHO, Reference Caldas and Cohen2008) and a lack of funding to ensure the continuity of community services (Mechanic and Rochefort, Reference Mechanic and Rochefort1990; McCubbin, Reference McCubbin1994; PAHO, Reference Caldas and Cohen2008). This is to secure a synchronicity between downsizing psychiatric hospitals and the scaling up of psychosocial interventions.

Knowledge/science

Conceptual barriers to promoting PDI were identified. Some authors consider that the lack of research on PDI processes (Bennett and Morris, Reference Bredenberg1983), paralyze or slow down policy planning and implementation (Shen and Snowden, Reference Shen and Snowden2014). At the conceptual level, reducing the concept of community care to narrow geographical proximity can limit the development of community-based interventions (Bennett and Morris, Reference Bennett and Morris1983).

Some authors criticized the inadequate transfer and use of certain service paradigms, such as the application of urban-centered interventions to rural locations (Kraudy et al., Reference Kraudy, Liberati, Asioli, Saraceno and Tognoni1987) without previous identification of rural specificities, creating a disconnection between users and facilities (Schmidt, Reference Schmidt2000).

Power, interests and influences

Barriers related to the conflict between the interests and perspectives of different groups were grouped under this category.

Authors have discussed the impact of the privatization of mental health care in the wake of the closure of psychiatric hospitals. Market-driven decisions can recreate similar conditions to those in old psychiatric facilities (Rose, Reference Rose1979). The rise of private hospitals in the United States and their reluctance to participate in non-profit services, such as working with existing public providers, influences access to and the nature of mental health care. Private for-profit hospitals may restrict access to care for uninsured patients (Dorwart et al., Reference Dorwart, Schlesinger, Davidson, Epstein and Hoover1991). Additionally, private insurance in the United States often encourages unnecessary hospitalization and discourages psychosocial interventions and alternative forms of treatment (Barton, Reference Barton1983; Freedman and Moran, Reference Freedman and Moran1984).

Furthermore, the low cost of hospitalization in some areas, as reported in Asia (Fakhoury and Priebe, Reference Fakhoury and Priebe2002), does not provide an economic incentive to push for deinstitutionalization.

The dependence of psychiatric research and development on drug-companies is seen as a barrier. McCubbin stated that the vested interests of the pharmaceutical industry may influence psychiatric practice by selectively supporting medical schools, conferences, and journals, potentially tuning the vision of community mental health into a market opportunity (McCubbin, Reference McCubbin1994).

Finally, the lack of relevance of mental health in the political agenda is a crucial, over-encompassing barrier to effective advocacy efforts (Mechanic and Rochefort, Reference Mechanic and Rochefort1990; Semke, Reference Semke1999; PAHO, Reference Caldas and Cohen2008), as is the uncoordinated and fragmentary nature of these efforts (Mechanic and Rochefort, Reference Mechanic and Rochefort1990; McCubbin, Reference McCubbin1994; Rosenheck, Reference Rosenheck2000).

Services and support in the community

The slow development of community programmes forced patients to return to long-term institutions, risking chronification (Kaffman et al., Reference Kaffman, Nitzan and Elizur1996). There have been reports of problems caused by the sudden decrease in psychiatric beds without corresponding increases in community-based services. This can result in unintended transfers of patients to other institution-based services and even imprisonment (Shen and Snowden, Reference Shen and Snowden2014). Inadequate training of community-based workers, discharge without community support (Shen and Snowden, Reference Shen and Snowden2014) and early release promoted by legislatively mandated PDI policies (Kleiner and Drews, Reference Kleiner and Drews1992) are elements to consider.

The authors identified several barriers to adequate integration of discharged users into their communities, including the absence of jobs and income (Goering et al., Reference Goering, Wasylenki, Lancee and Freeman1984), inadequate housing (Grabowski et al., Reference Grabowski, Aschbrenner, Feng and Mor2009), and insufficient public support (Manuel et al., Reference Manuel, Hinterland, Conover and Herman2012). Other barriers included challenging behaviors (Allen et al., Reference Allen, Lowe, Moore and Brophy2007), old age (Barry et al., Reference Barry, Blow, Dornfeld and Valenstein2002), and pessimistic attitudes and feelings of disempowerment and hopelessness among patients (Chopra and Herrman, Reference Chopra and Herrman2011). In addition, the decrease in disability pensions following an increase in earned income was also identified as a barrier to social integration, as it can discourage work (Chopra and Herrman, Reference Chopra and Herrman2011).

Workforce

Barriers related to the workforce in both institutionalized settings and community services were identified. Regarding human resources, authors mentioned staff shortages as a barrier for the transition toward community-based care (Rose, Reference Rose1979; Stelovich, Reference Stelovich1979; Fakhoury and Priebe, Reference Fakhoury and Priebe2002; Shen and Snowden, Reference Shen and Snowden2014). Another barrier reported was the internal frictions and the existence of opposing views about care and rehabilitation (Kaffman et al., Reference Kaffman, Nitzan and Elizur1996; O’Doherty et al., Reference O’Doherty, Linehan, Tatlow-Golden, Craig, Kerr, Lynch and Staines2016). More specifically, the psychiatric hospital workforce can delay or hinder the transformation of psychiatric institutions for fear of losing their livelihoods (Swidler and Tauriello, Reference Swidler and Tauriello1995; Shen and Snowden, Reference Shen and Snowden2014). Workers can express reluctance and skepticism regarding the feasibility of community living for institutionalized persons (Mayston et al., Reference Mayston, Alem, Habtamu, Shibre, Fekadu and Hanlon2016; O’Doherty et al., Reference O’Doherty, Linehan, Tatlow-Golden, Craig, Kerr, Lynch and Staines2016). This includes the development of unfair expectations toward family members, which alienated carers and hindered their willingness to accept responsibility (Barton, Reference Barton1983).

On the other hand, service providers located in the community can be sources of stigma, expressed in the avoidance of formerly institutionalized patients (Barton, Reference Barton1983), hopelessness toward treatment (Aggett and Goldberg, Reference Aggett and Goldberg2005), exclusion of users from constructing their treatment plan (Bryant et al., Reference Bryant, Craik and McKay2004) and fears stemming from the lack of restraining measures (Ash et al., Reference Ash, Suetani, Nair and Halpin2015). Perceived racism at the hands of service providers can lead to mistrust in patients, causing them to either reject treatment or have poor adherence, which in turn can result in poorer outcomes, such as a longer hospital stays (Chakraborty et al., Reference Chakraborty, King, Leavey and McKenzie2011).

Communities and the public

Factors limiting social inclusion, comprising attitudes toward persons with SMI and community responses to PDI processes, were grouped under this category. Lack of preparation and stigma (Bredenberg, Reference Bredenberg1983; Mechanic and Rochefort, Reference Mechanic and Rochefort1990; Fakhoury and Priebe, Reference Fakhoury and Priebe2002; Aggett and Goldberg, Reference Aggett and Goldberg2005; PAHO, Reference Caldas and Cohen2008; Manuel et al., Reference Manuel, Hinterland, Conover and Herman2012; Chan and Mak, Reference Chan and Mak2014; O’Doherty et al., Reference O’Doherty, Linehan, Tatlow-Golden, Craig, Kerr, Lynch and Staines2016) leads to hostile attitudes toward service-users challenging social integration (Bredenberg, Reference Bredenberg1983; Fakhoury and Priebe, Reference Fakhoury and Priebe2002; Aggett and Goldberg, Reference Aggett and Goldberg2005; PAHO, Reference Caldas and Cohen2008; O’Doherty et al., Reference O’Doherty, Linehan, Tatlow-Golden, Craig, Kerr, Lynch and Staines2016). The attribution of dangerousness to individuals with SMI and the public acceptance of social control measures over recovery-oriented alternatives were also reported as barriers to PDI processes (Fakhoury and Priebe, Reference Fakhoury and Priebe2002; Matsea et al., Reference Matsea, Ryke and Weyers2019).

Family/carers

Authors highlighted the difficulties in maintaining relationships between caregivers and community services (Barton, Reference Barton1983; McCubbin, Reference McCubbin1994; Aggett and Goldberg, Reference Aggett and Goldberg2005; Yip, Reference Yip2006; Lavoie-Tremblay et al., Reference Lavoie-Tremblay, Bonin, Bonneville-Roussy, Briand, Perreault, Piat, Lesage, Racine, Laroche and Cyr2012; Mayston et al., Reference Mayston, Alem, Habtamu, Shibre, Fekadu and Hanlon2016; O’Doherty et al., Reference O’Doherty, Linehan, Tatlow-Golden, Craig, Kerr, Lynch and Staines2016). Previous experiences of failed treatments can lead to lack of cooperation and hostility toward services (Aggett and Goldberg, Reference Aggett and Goldberg2005). Professionals can be reluctant to cooperate and skeptical about the feasibility of community living (Mayston et al., Reference Mayston, Alem, Habtamu, Shibre, Fekadu and Hanlon2016; O’Doherty et al., Reference O’Doherty, Linehan, Tatlow-Golden, Craig, Kerr, Lynch and Staines2016). Families and caregivers may have concerns about community living and its suitability for people with high support needs (O’Doherty et al., Reference O’Doherty, Linehan, Tatlow-Golden, Craig, Kerr, Lynch and Staines2016) and concerns about receiving the burden of care, and this can alienate them and hinder their willingness to accept responsibility.

Facilitators to the process of psychiatric deinstitutionalization

Facilitators in the process were organized under six categories summarized in Table 6 and described in detail below.

Planning, leadership and funding

Factors related to organizational and managerial capacities required for the transition were grouped under this category. Authors stated that the presence of a central mental health authority increased the potential to ensure effective coordination. For example, Latin America and Caribbean countries have developed mental health units within the health ministry capable of overseeing coordination (PAHO, Reference Caldas and Cohen2008). Coordination across countries in the initial phases of reform played a crucial role, by sharing technical support and experiences of implementation (PAHO, Reference Caldas and Cohen2008). Authors highlighted the relevance of developing intersectoral coordination, which may act as a safety net for persons with serious mental health illness reducing acute episodes (PAHO, Reference Caldas and Cohen2008).

Studies mentioned how increases in psychiatric population and fiscal strain on state mental hospitals drove governments to develop an alternative mental health strategy (Mechanic and Rochefort, Reference Mechanic and Rochefort1990; McCubbin, Reference McCubbin1994). The pressure on fiscal resources -partly linked to economic crisis- made the costs of mental health hospitals and their inefficiency more apparent (PAHO, Reference Caldas and Cohen2008). Also, the direct transference of funds – from reduced hospital expenditure – to community-based services was mentioned as a factor that fostered the transference of patients from state hospitals to alternative placements in the community (Mechanic and Rochefort, Reference Mechanic and Rochefort1990). Finally, the growth of disability insurance was understood as a facilitator of the process of discharging service users from psychiatric hospitals by contributing to their support in the community (Mechanic and Rochefort, Reference Mechanic and Rochefort1990).

Knowledge/science

Interdisciplinary research focusing on the legal and economic factors which influence PDI processes and practices was valued (Mechanic and Rochefort, Reference Mechanic and Rochefort1990; PAHO, Reference Caldas and Cohen2008). The elucidation of adverse effects of institutions on individual patients (Bennett and Morris, Reference Bennett and Morris1983; Mechanic and Rochefort, Reference Mechanic and Rochefort1990; Kleiner and Drews, Reference Kleiner and Drews1992; Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Lakin, Mangan and Prouty1998) together with the documentation of human rights violations in mental health hospitals helped in catalyzing the reform process (Bennett and Morris, Reference Bennett and Morris1983; PAHO, Reference Caldas and Cohen2008). More generally, some authors stressed that conceptual clarity regarding the application of a biopsychosocial model to the mental health field (McCubbin, Reference McCubbin1994) and the interpersonal aspect of mental health (Bennett and Morris, Reference Bennett and Morris1983; Kleiner and Drews, Reference Kleiner and Drews1992) helped in the rolling up of the Deinstitutionalisation processes.

In the early stages of PDI in the USA, the allocation of research grants to state mental health hospitals developing pilot testing of outpatient treatment and rehabilitation helped in the shift of funds from mental hospitals into general hospitals (Weiss, Reference Weiss1990). The dissemination of early experiences of innovative policy implementation in mental health facilitated the adoption of Deinstitutionalisation practices in other regions (Shen and Snowden, Reference Shen and Snowden2014). Finally, the development of psychotropic medication and the reduction of psychiatric symptomatology helped to build trust in the implementation of less coercive management plans that were feasible to apply at the community level (Bennett and Morris, Reference Bennett and Morris1983; Bredenberg, Reference Bredenberg1983; Freedman and Moran, Reference Freedman and Moran1984; Mechanic and Rochefort, Reference Mechanic and Rochefort1990; Kleiner and Drews, Reference Kleiner and Drews1992; Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Lakin, Mangan and Prouty1998).

Power, interests and influences

This category points to the role of social movements and organizations in influencing the development of Deinstitutionalisation processes. This includes advocacy actions and legal transformations.

Mental health professional groups and civil society organizations were seen as key agents contributing to overcome stigma and change the delivery of mental health services (Weiss, Reference Weiss1990). Some authors emphasized the importance of promoting the active involvement of civil society groups (Oshima and Kuno, Reference Oshima and Kuno2006). Finally, authors highlight how the internationalization of mental health reforms puts increasing pressure on other countries to jump on the “bandwagon” to avoid appearing antiquated (Shen and Snowden, Reference Shen and Snowden2014).

Recognition of the rights of people with disabilities and their defense by civil rights movements fostered the development of new mental health laws promoting less restrictive therapeutic alternatives and broader transformations on mental health systems (Freedman and Moran, Reference Freedman and Moran1984; Mechanic and Rochefort, Reference Mechanic and Rochefort1990; Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Lakin, Mangan and Prouty1998; PAHO, Reference Caldas and Cohen2008; Shen and Snowden, Reference Shen and Snowden2014). These changes involved expanding the supply of options in the community (Freedman and Moran, Reference Freedman and Moran1984; Mechanic and Rochefort, Reference Mechanic and Rochefort1990; Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Lakin, Mangan and Prouty1998; PAHO, Reference Caldas and Cohen2008) and relocating investment from institutions to community services (Swidler and Tauriello, Reference Swidler and Tauriello1995). In some countries, an extensive and strong network of community-based organizations provided opportunities for community participation, facilitating the effective integration of patients into the community (PAHO, Reference Caldas and Cohen2008). This was accompanied by the divulgation of reports showing mistreatment of patients in hospitals, pushing public sensitivity against asylums (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Lakin, Mangan and Prouty1998).

Services and supports in the community

This category describes how the characteristics and distribution of community-based services and support for persons with SMI acted as facilitators in PDI processes.

Authors noted how policies around prevention in mental health, the integration of mental health services in primary health care centers (Kraudy et al., Reference Kraudy, Liberati, Asioli, Saraceno and Tognoni1987; PAHO, Reference Caldas and Cohen2008) and the accessibility of services (Mayston et al., Reference Mayston, Alem, Habtamu, Shibre, Fekadu and Hanlon2016), together with social support such as supplementary income, can sustain community inclusion (Lamb and Goertzel, Reference Lamb and Goertzel1977), giving sustainability to Deinstitutionalisation. Adequate coordination across community-based services allowed the adequate externalization of users with complex needs (Cohen, Reference Cohen1983; Conway et al., Reference Conway, Melzer and Hale1994; Evans et al., Reference Evans, Okeke, Ali, Achara-Abrahams, Ohara, Stevenson, Warner, Bolton, Lim, Faith, King, Davidson, Poplawski, Rothbard and Salzer2012). Scaled-up outpatient facilities including local acute hospitals and intermediate facilities (Bennett and Morris, Reference Bennett and Morris1983; Abas et al., Reference Abas, Vanderpyl, Le Prou, Kydd, Emery and Foliaki2003) were key in allowing mental health systems to reduce their reliance on inpatient care and limiting beds in psychiatric settings (PAHO, Reference Caldas and Cohen2008). Plans to end seclusion and to support mental health professionals toward a transformation in their clinical practice were identified as a facilitator to the transition (Ash et al., Reference Ash, Suetani, Nair and Halpin2015).

Other facilitators included the continuity of care after discharge (Sytema et al., Reference Sytema, Micciolo and Tansella1996) and specific actions such as: developing mobile teams and home interventions as they facilitate access to service for users who cannot physically access needed services (John et al., Reference John, Venkatesan, Tharyan and Bhattacharji2010), mitigating self-stigma dynamics by allowing an active participation of users in their treatment through shared decision-making with professional staff (Chan and Mak, Reference Chan and Mak2014; Mayston et al., Reference Mayston, Alem, Habtamu, Shibre, Fekadu and Hanlon2016; Matsea et al., Reference Matsea, Ryke and Weyers2019) and supporting mechanisms for primary care workers such as a 24 h hotline for assistance when it is required (Huang et al., Reference Huang, Poremski, Goh, Hendriks and Fung2017).

In terms of training, it is argued that a reform such as PDI requires the development of an educational infrastructure including local health training networks for continuing education and training needs, and targeting providers, service-users, volunteers, family members and others (Wasylenki and Goering, Reference Wasylenki and Goering1995). The incorporation of non-specialized, community-based workers trained on mental health prevention and promotion is also highlighted (Mayston et al., Reference Mayston, Alem, Habtamu, Shibre, Fekadu and Hanlon2016).

Expanding user’s freedom to choose among service options was a central facilitator. This includes models of self-directed care, where users are given a budget to choose between service options (Kalisova et al., Reference Kalisova, Pav, Winkler, Michalec and Killaspy2018). Experiences from the US, Germany and England show that patients used their budget to pay for care from their relatives, avoiding the use of institutionalized settings and preventive care options, thus shifting from crisis intervention to early interventions (Alakeson, Reference Alakeson2010). Self-directed care improved user’s autonomy and has proved to be an effective preventive intervention (Alakeson, Reference Alakeson2010).

Workforce

Facilitators related to community mental health services workforce were organized under this category. Strategies around training and skills include enhancing psychiatric aspects in health curriculum and provision of grants to complete training and research projects. This attracted students from other professions to the community mental health field (Weiss, Reference Weiss1990). Having previous experience in general medicine before training into psychiatry appeared to support a culture of community-based work and a strong collaboration with primary care teams (PAHO, Reference Caldas and Cohen2008).

Exogenous factors

Factors indirectly affecting the feasibility of implementing Deinstitutionalisation policies were gathered under this category. This includes the role of exogenous shocks (e.g., conflict and humanitarian disasters) (Shen and Snowden, Reference Shen and Snowden2014) in bringing wider public attention to patients’ living conditions. A study also mentioned how the end of dictatorial regimes brought attention to human rights issues in psychiatric care, facilitating the process of Deinstitutionalisation in countries such as Argentina, Brazil and Chile (PAHO, Reference Caldas and Cohen2008).

Discussion

A marked decline in interest on psychiatric institutions across the global mental health literature has been noted by Cohen and Minas (Reference Cohen and Minas2017) being absent from important prioritization exercises like the Grand Challenges in Global Mental Health (Collins et al., Reference Collins, Patel, Joestl, March, Insel, Daar and Walport2011). The authors argue that although establishing high-quality community mental health services is crucial for improving the lives of people with severe mental disorders, an exclusive focus scalability overlooks ongoing deficiencies in treatment quality and human rights protections in psychiatric institutions. Given their role in human rights abuses experienced by people with mental disorders, PDI efforts should receive more attention.

In response to this call, this article organized the available evidence around PDI, to assist in planning and conducting contextually relevant studies about and for the process. Drawing on the review, the following section introduces a set of proposals while reflecting on the limitations and problems with the available literature.

Moving psychiatric deinstitutionalization forward

The transition from a system centered on long-term psychiatric hospital care to one centered on community-based services is complex, usually prolonged and requires adequate planning, sustained support and careful intersectoral coordination. The literature documenting and discussing PDI processes is vast, running across different time periods, regions, socio-political circumstances, and disciplines, and involving diverse models of institutional and community-based care. Based on this scoping review, we propose five key considerations for researchers and policymakers involved in PDI efforts:

-

1) Needs assessment, design and scaling up. An adequate assessment of the institutionalized population is required, to shape existing and new community-based services around their needs and preferences. A thorough analysis of the correlation of forces required to unlock institutional inertia is crucial.

-

2) Financing the transition. A comprehensive and sustainable investment is necessary, and the different aspects of the transition should be adequately costed, including new facilities, support of independent living, training, new professional roles, and the reinforcement of primary health care.

-

3) Workforce development. The workforce should be aligned with the transition from the outset. Elements such as training, incentives and guarantees of job stability are required. Curricular changes in psychiatric training, including more emphasis on community-based care and recovery-oriented practices, are necessary.

-

4) PDI implementation. The implementation process requires political resolve, careful monitoring, and an ability to respond to unexpected challenges. PDI represents a crucial learning opportunity for further scaling up.

-

5) Monitoring and quality assurance. Results of the process need to be carefully assessed against clear operational goals. The perspectives of users, caregivers, and the workforce should be incorporated into the assessments. The development of an assessment strategy detailing clear outcomes that incorporate financial and organizational dimensions is advised. Thorough documentation of PDI process, including achievements and setbacks should be done to build a reliable and diverse evidence-base for action.

A multifaceted strategy, clear and strong leadership, participation from diverse stakeholders and long-term political and financial commitment are basic elements in the planning of PDI processes. Nonetheless, implementation dynamically responds to local conditions, widely differing across countries and regions. What appears as a barrier or a facilitator can vary according to a specific context.

Although this review focuses on the barriers and facilitators for processes of PDI, we recognize that outcomes are important, and they cannot be separated from processes. Misconceptions about outcomes can hinder PDI efforts, and failed processes can lead to negative outcomes.

Two misconceptions are common. The first suggests a strong correlation between decreasing psychiatric beds and increasing homelessness or imprisonment among people with mental health problems. However, in their analysis of 23 cohort studies, Winkler et al. (Reference Winkler, Barrett, McCrone, Csémy, Janousková and Höschl2016) found that homelessness and imprisonment occurred only sporadically, and, in most studies, cases of homelessness or imprisonment were not reported.

The second misconception considers that PDI can be negative for formerly institutionalized individuals. In his review on the impact of deinstitutionalization on discharged long-stay patients, mainly diagnosed with schizophrenia, Kunitoh (Reference Kunitoh2013) found that most studies reported favorable changes in social functioning, stability and improvements in psychiatric symptoms, and positive changes in quality of life and participant attitudes toward their environment, at various time-points. Deterioration following deinstitutionalization was rare. This suggests that even long-stay patients, who commonly experience functional impairment due to schizophrenia, can achieve better functioning through deinstitutionalization.

At the same time, failure at the level of process – including planning and implementation – can lead to negative and even fatal outcomes for patients. In South Africa, from October 2015 to June 2016, a poorly executed attempt to relocate 1,711 highly dependent patients resulted in 144 deaths and 44 missing individuals (Freeman, Reference Freeman2018). This tragedy stemmed from ethical, political, legal, administrative, and clinical errors. Reports examining this failure offer valuable lessons for PDI efforts globally (Wessels and Naidoo, Reference Wessels, Naidoo, Wessels, Potgieter and Naidoo2021).

Limitations in the literature: Time, space, process and voice

The literature on PDI is diverse, which makes synthesis endeavors difficult. Although promoted as a global standard in psychiatric and social care, the multiplicity of contexts in which the policy has been implemented limits the possibility of finding common ground. In their systematic review of the current evidence on mental health and psychosocial outcomes for individuals residing in mental health-supported accommodation services, McPherson et al. (Reference McPherson, Krotofil and Killaspy2018) noted how the variation in service models, the lack of definitional consistency, and poor reporting practices in the literature stymie the development of adequate synthesis.

Similarly, in a recent systematic review of psychiatric hospital reform in LMICs, Raja et al. (Reference Raja, Tuomainen, Madan, Mistry, Jain, Easwaran and Singh2021, p. 1355) expressed regret over the “dearth of research on mental hospital reform processes,” indicating how poor methodological quality and the existence of variation in approach and measured outcomes challenged the extrapolation of findings on the process or outcomes of reform. Of the 12 studies they selected, 9 of them were rated as weak according to their quality assessment.

Beyond the challenges posed to synthesis efforts and through conducting this review, we identified four wider problems affecting the literature documenting PDI planning and implementation. They are related to time, location, focus, and voice.

In terms of time, most of the work addressing PDI was developed at the end of the 1970s through the 1980s and early 1990s. After this, there are barriers and facilitators documented which indirectly relate to the development of community-based services and their evaluation, with PDI as the “background” but not as the main object of attention. Also, the date of the search – May 2020 – could potentially exclude studies that worked with data from the pre-COVID period.

When it comes to location, while there is a wealth of literature on the topic, it is important to note that much of it is based on the experiences of the USA and Western Europe. The documentation of PDI in regions outside of the “global north” is typically limited to personal testimonies from process leaders, which may lack systematicity and are usually published in languages other than English. This can restrict their accessibility and dissemination.

In terms of focus, most studies have a clinical orientation, evaluating various outcomes that are directly or indirectly related to PDI. However, the process itself, has received little attention. An exclusive emphasis on outcomes can obscure the administrative, legal, and political complexities of carrying out a psychiatric reform, this, hinder the dissemination of important lessons.

Finally, it is worth noting that important voices are often missing from available studies and reports on PDI processes. While some studies do consider the experiences and engagement of caregivers, healthcare workers, and patients, they are still in the minority. This can create a skewed understanding of the impact of PDI, as these individuals play crucial roles in shaping the process and its outcomes. The same goes for the different communities where patients have developed their lives after PDI.

These limitations have significant consequences. It is unclear whether the evidence extracted from experiences in high-income countries in North America and Europe can directly inform processes in other regions, including low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). While it is possible to identify common pitfalls, barriers, and needs, this identification must be accompanied by up-to-date local research to ensure that the evidence is relevant and applicable to specific contexts.

The involvement of patients and communities affected by institutionalization in the design and implementation of research and policy should be central in a renewed PDI agenda. The recently launched Guidelines on deinstitutionalization, including in emergencies, by the United Nations Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities represent a pioneering effort in this direction (OHCHR, 2022).

At the same time, qualitative and ethnographically oriented case studies are required to closely examine PDI efforts while remaining attentive to diversity and local creativity beyond global normative parameters of success and failure. Furthermore, reflexive, and flexible approaches to research synthesis are necessary to capture and assess the wealth of lessons learned from diverse engagements with deinstitutionalization across the globe.

This article offers a preliminary and general classification of barriers and facilitators that can inform the development of relevant research through various methodologies and other literature. The categories can be modified and customized based on the evidence from various settings. As far as we know, this classification is not yet present in the existing literature.

Conclusion

Institutional models of care continue to dominate mental health service provision and financing in many countries, leading to a continued denial of the right to freedom and a life in the community for individuals with mental health conditions and associated disabilities. The successful implementation of PDI requires detailed planning, sustained support and coordinated action across different sectors.

This review identifies the factors impacting PDI processes, according to the available literature. Barriers and facilitators are organized in 15 thematic groups. The results reveal that PDI processes are complex and multifaceted, requiring detailed planning and commensurate financial and political support. We have offered five considerations for policymakers and researchers interested and/or involved in PDI efforts.

There are many lessons to be learned from the processes described in the literature, and many areas where research has been insufficient. Barriers and facilitators will differ in response to the legal, institutional, and political characteristics of each region and country. This categorization can be adapted to national realities and different levels of policy progress in PDI, to guide research and policy efforts. We call for methodological innovation and the involvement of affected communities as key elements of a renewed research agenda around this neglected aspect of mental health reform worldwide.

Open peer review

To view the open peer review materials for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2023.18.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2023.18.

Data availability statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article (and/or its Supplementary Materials).

Acknowledgments

This work was made possible by the financial support of the Chilean Agency for Research and Development (ANID), under the Initiation Fondecyt grant Number 11191019.

Author contribution

M.I.D. and C.M.C. conceived the idea for the project. J.U.O. and C.M.C. developed the framework to conduct the systematic search, which J.G.M. performed. J.U.O. and J.G.M. established the eligibility of articles under the supervision and with the contribution of C.M.C. J.G.M. and J.U.O. extracted the data of the selected articles. J.G.M., J.U.O. and C.M.C. coded the article contents and created the categories iteratively through rounds of revision and adjustment. J.U.O. and C.M.C. produced an early draft of the manuscript. F.T. reviewed several versions of the manuscript. The final manuscript was discussed and improved by all the authors. C.M.C. and J.U.O. coordinated the development of the manuscript.

Competing interest

The authors declare none.

Comments

No accompanying comment.