Introduction

Duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) describes the period between initial psychotic symptoms and engagement in recommended treatments, and typically lasts 1–2 years [Reference McGlashan1, Reference Barnes, Hutton, Chapman, Mutsatsa, Puri and Joyce2]. Delayed access to treatment predicts poorer clinical and social outcomes up to 8 years later [Reference Crumlish, Whitty, Clarke, Browne, Kamali and Gervin3–Reference Sullivan, Carroll, Peters, Amos, Jones and Marshall6]. This comes at considerable personal and healthcare costs [Reference Boonstra, Klaassen, Sytema, Marshall, De Haan and Wunderink7–Reference Valmaggia, McCrone, Knapp, Woolley, Broome and Tabraham9], leading the World Health Organization [10] to identify DUP as an international healthcare target.

Specialist early intervention services have been established in Australia, New Zealand, and the UK, and more recently in North America, Asia, Scandinavia, and other European countries, with the aim of identifying and treating early symptoms of psychosis over the initial critical period [Reference McGorry and Killackey11–Reference Maric, Petrovic, Raballo, Rojnic‐Kuzman, Klosterkötter and Riecher‐Rössler13]. These services have been well received by young people with psychosis [Reference Lester, Marshall, Jones, Fowler, Amos and Khan14], with some evidence of improved outcomes [Reference Larsen, Melle, Auestad, Haahr, Joa and Johannessen15]. Disappointingly, however, the expectation that this step change in service delivery would lead to overall reductions in DUP is not (yet) supported by the literature [Reference Singh16], leading to calls to identify and target barriers and facilitators to accessing these services [Reference Birchwood, Connor, Lester, Patterson, Freemantle and Marshall17].

A recent systematic review of the barriers and facilitators to successful implementation of early intervention services highlighted systemic (e.g., funding and organizational structures), service (e.g., coherence of provision), and staff (e.g., knowledge and attitudes) factors [Reference O’Connell, O’Connor, McGrath, Vagge, Mockler and Jennings18]. A linked but distinct question concerns the factors affecting the likelihood that people will seek access to early intervention services. To our knowledge, this is the first review of barriers and facilitators to seeking access to early intervention for psychosis services.Footnote 1

Methods

Broad methodological alignment with O’Connell et al. [Reference O’Connell, O’Connor, McGrath, Vagge, Mockler and Jennings18] allows comparison across these two complementary reviews.

Pre-registration and search procedure

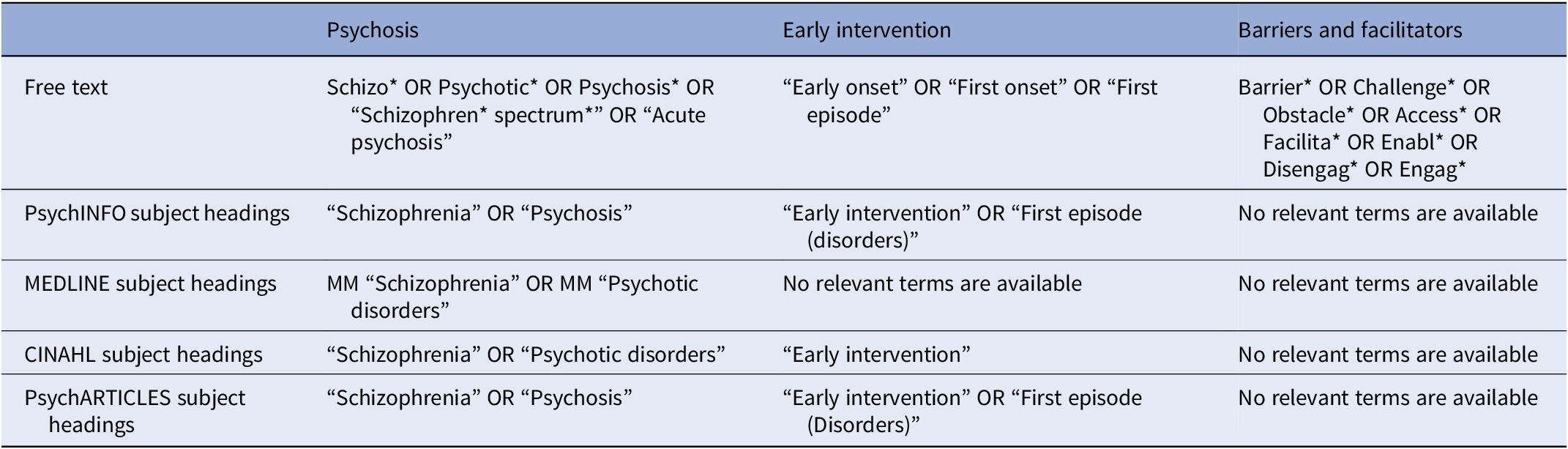

The review was pre-registered on PROSPERO (ID: CRD42022377155) and follows the preferred reporting guidelines for systematic reviews (PRISMA) [Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman and Group21]. We searched four electronic databases on 18.09.23 (PsychINFO, MEDLINE, CINAHL, and PsychARTICLES) using free text and subject headings (where applicable) to improve search accuracy (see Table 1). Additionally, we searched ProQuest, Ethos, and British Library databases for gray literature to ensure a comprehensive search and reduce the risk of publication bias [Reference Boland, Dickson and Cherry22].

Table 1. Free text and subject headings

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

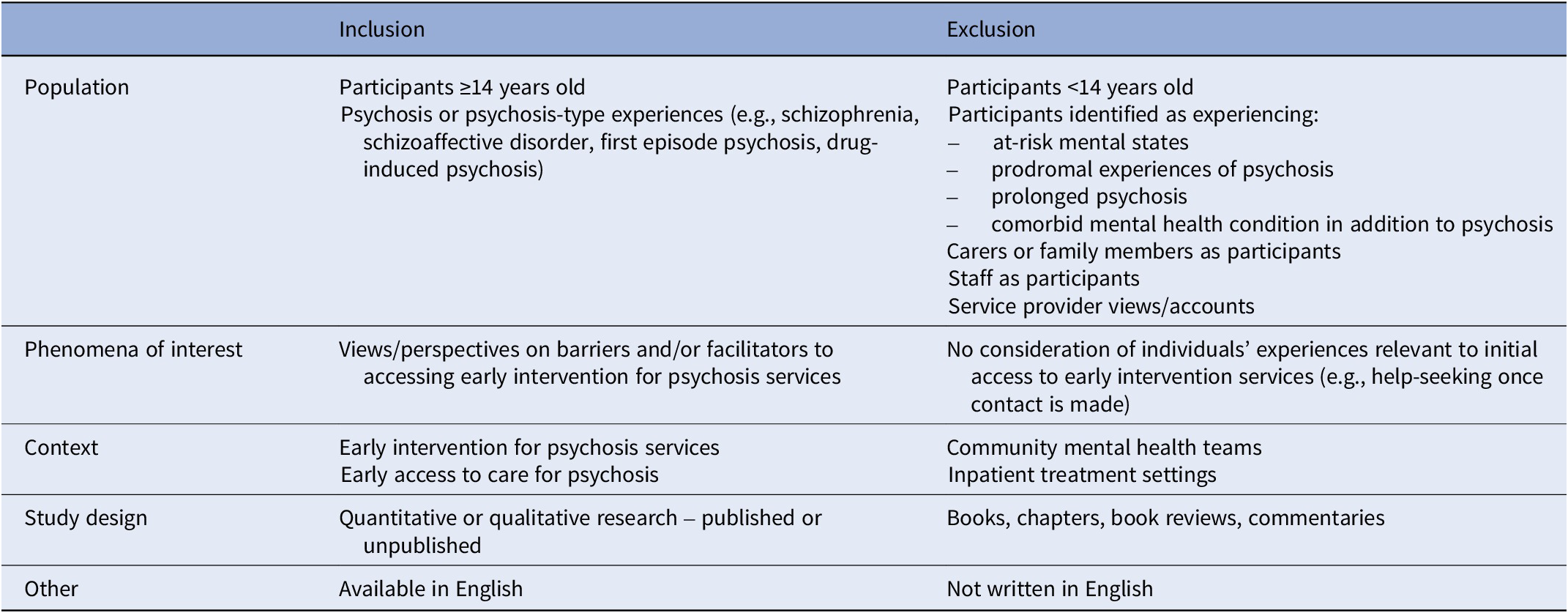

Table 2 outlines study eligibility criteria, following Butler et al. [Reference Butler, Hall and Copnell23]. The search was not limited by publication date or status, to ensure a balanced summary of the evidence and reduce the impact of publication bias [Reference Paez24].

Table 2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The perspectives of carers, family members, and staff are also important in understanding access to services. However, these may diverge in important ways from the views of service users themselves, and so we focus on people with psychosis in the current review.

Study selection, data extraction, and analysis plan

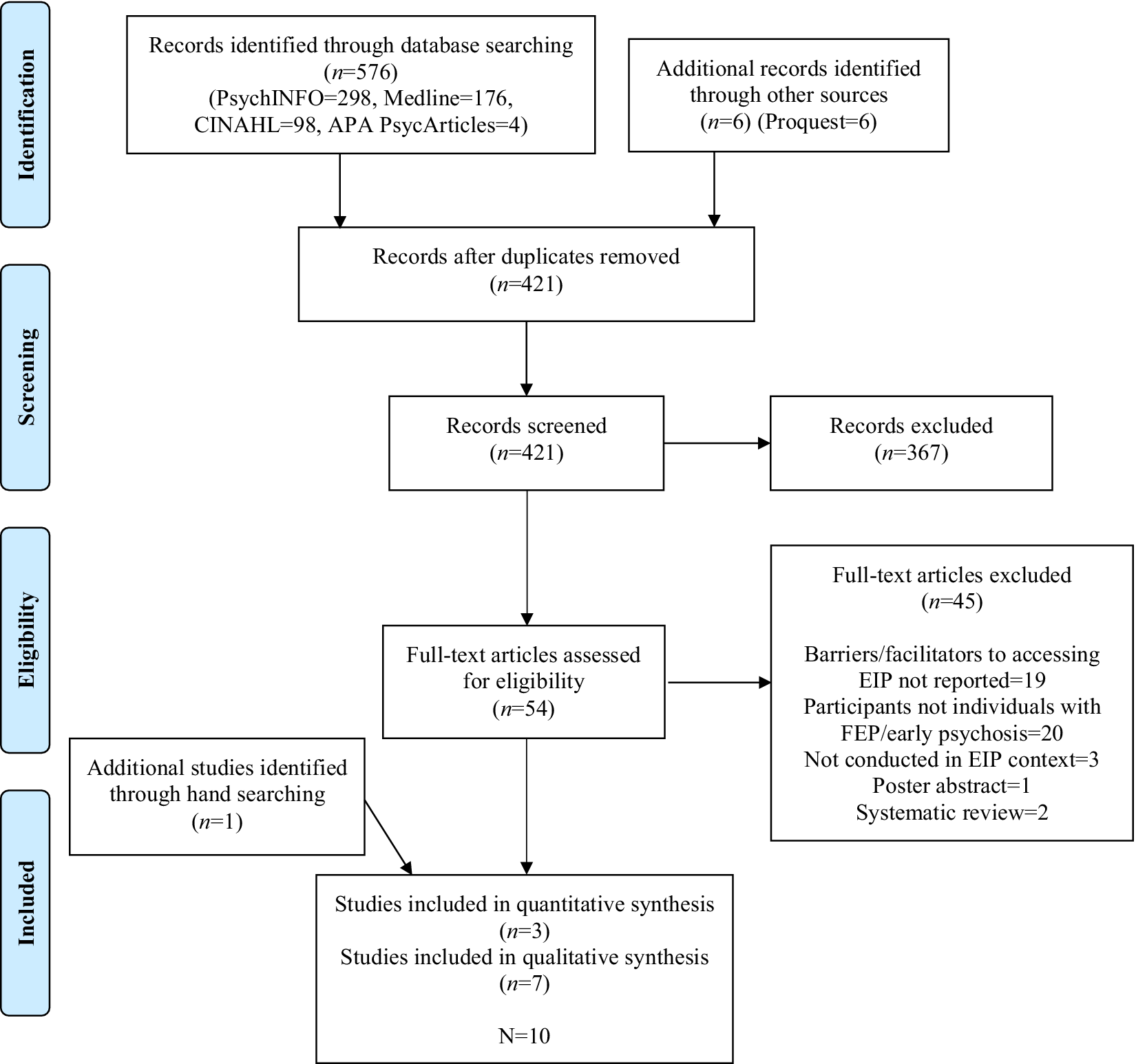

We used Rayyan reference management software [Reference Ouzzani, Hammady, Fedorowicz and Elmagarmid25] to collate search results. The search yielded 582 articles, 421 after duplicates were removed. An independent reviewer second rated 10% of abstracts (n = 38) with good agreement (84.2%)Footnote 2 [Reference Fleiss, Levin and Paik26]. Full-text screening and hand searching of selected papers resulted in the identification of 10 papers which described three quantitative [Reference Birchwood, Connor, Lester, Patterson, Freemantle and Marshall17, Reference Archie, Akhtar-Danesh, Norman, Malla, Roy and Zipursky27, Reference Kular, Perry, Brown, Gajwani, Jasini and Islam28] and seven qualitative studies [Reference Bay, Bjørnestad, Johannessen, Larsen and Joa29–Reference Lee, Marandola, Malla and Iyer35] (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. PRISMA diagram for paper selection.

With just three quantitative studies measuring differing primary outcomes, a narrative summary of the characteristics and key results was indicated rather than a meta-analysis. In line with Cochrane recommendations for synthesizing qualitative research, we undertook a thematic synthesis of the qualitative studies [Reference Booth, Noyes, Flemming, Gerhardus, Wahlster and Van Der Wilt36–Reference Noyes, Booth, Cargo, Flemming, Harden, Harris, Higgins, Thomas, Chandler, Cumpston, Li, Page and Welch38]. This approach is positioned between integrative and interpretative approaches and includes: (1) line by line coding of individual study results (for which we used NVIVO, [Reference NVivo39]), (2) generating descriptive themes, and then (3) generating analytical themes which interpret qualitative data across primary studiesFootnote 3 [Reference Thomas and Harden40].

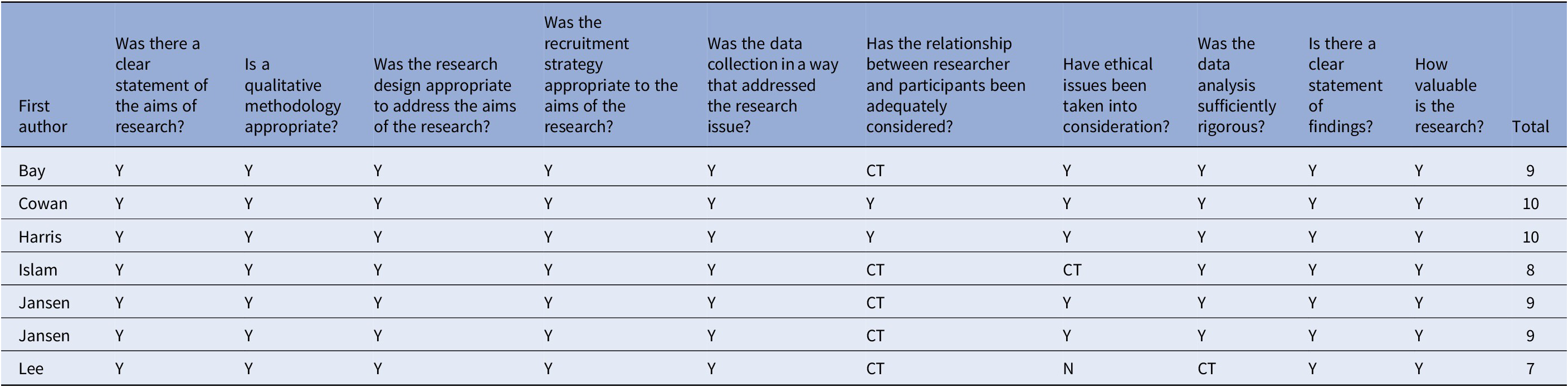

Quality assessment and risk of bias

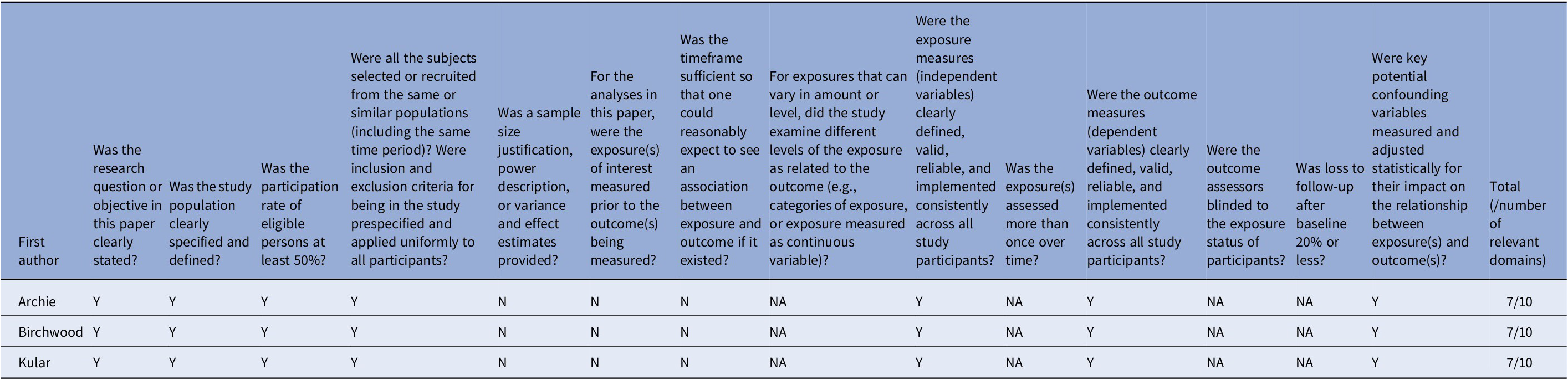

The Study Quality Assessment Tool (SQAT) [41] for observational studies, and the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) [Reference Long, French and Brooks42] checklist for qualitative studies include 14 and 10 items respectively to assess methodological, analysis, and interpretation bias. In line with previous reviews, we totaled the number of “Yes” responses [cf. Reference Al-Dirini, Thewlis and Paul43]. Quantitative studies scored 7/10 relevant domains (see Table 3) and qualitative studies scored at least 7/10 (see Table 4). The key limitation of the quantitative studies was the reliance on cross-sectional data which precludes causal inferences. Though strong in most domains, the majority of qualitative studies failed to address researcher reflexivity and the impact of researcher/participant interactions, which are key to rigorous qualitative designs [Reference Teh and Lek44, Reference Dodgson45].

Table 3. Quality assessment – quantitative studies

Abbreviations: CD, cannot determine; N, no; NA, not applicable; NR, not reported; Y, yes.

Table 4. Quality assessment – qualitative studies

Abbreviations: CT, cannot tell; N, no; Y, yes.

Quality assessments were completed by two raters independently with excellent agreement (100% SQAT; 95.71% CASP). Initial discrepancies with the CASP were resolved through discussion with the supervisory team. The quality assessment was not used to exclude studies (following Noyes et al. [Reference Noyes, Booth, Flemming, Garside, Harden and Lewin46] who note that domains are not equally weighted and so cut-off scores are arbitrary).

Researcher reflexivity

Reflexivity is a key element of qualitative research and requires researchers to consider their own role in the study and how this may influence findings [Reference Dodgson45]. This study was completed as part of the first author’s doctoral research. The second and third authors are experienced clinicians and researchers in the field. All three are healthcare professionals with experience in collecting data in early intervention services. We reflected on our roles, experiences, and assumptions during the thematic synthesis process to reduce the risk of bias [Reference McCabe and Holmes47].

ResultsFootnote 4

Study characteristics

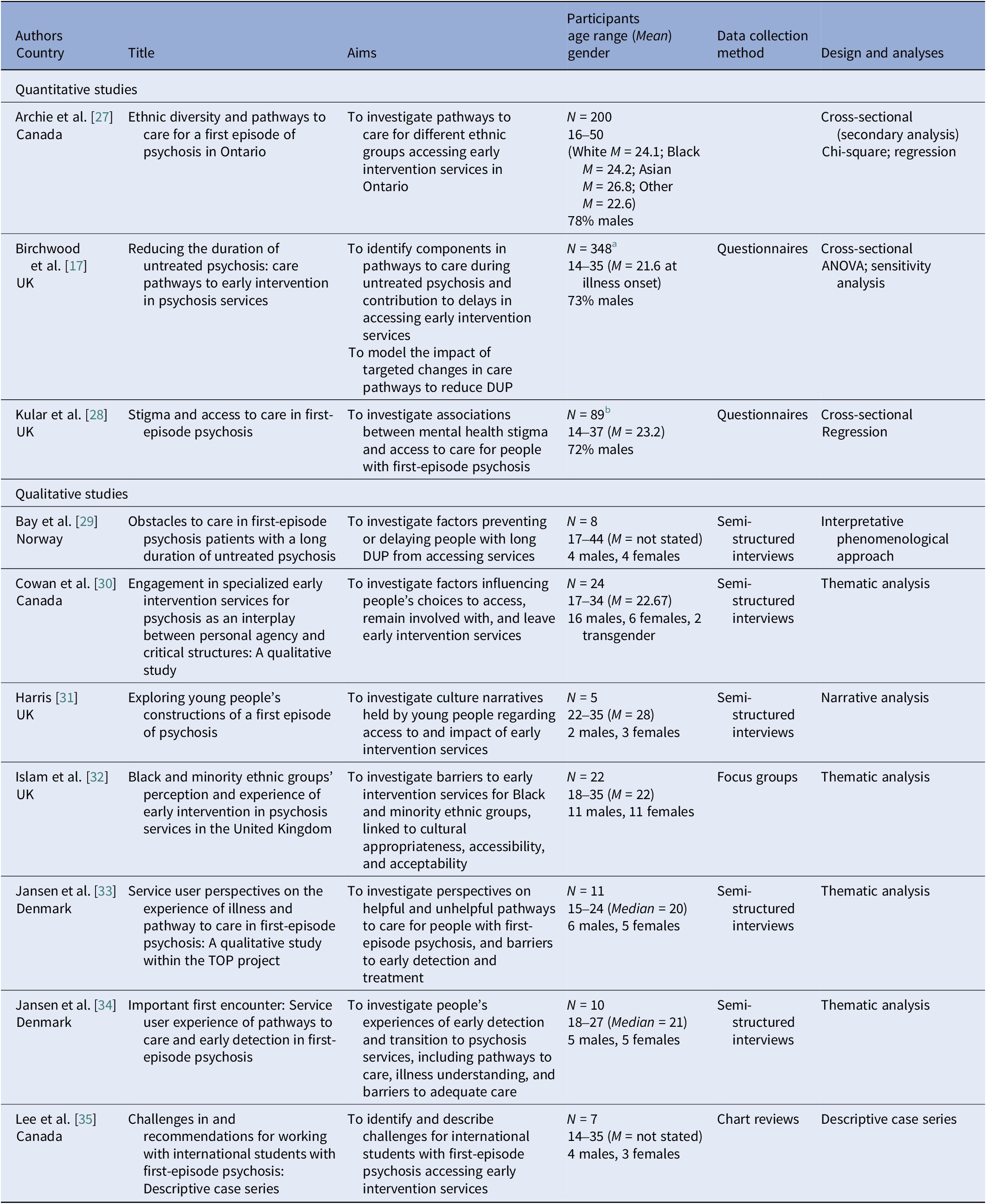

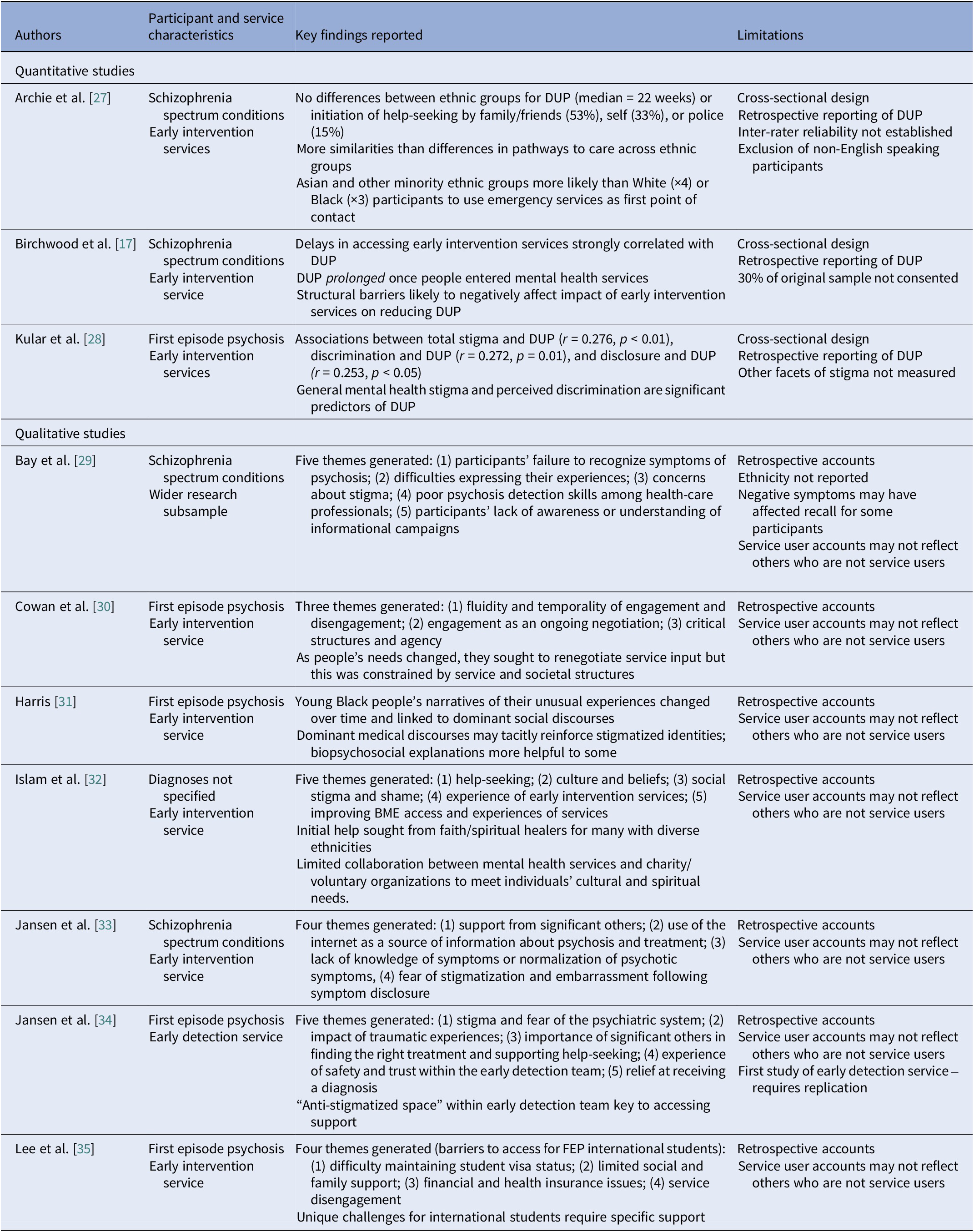

All three quantitative studies and six of the seven qualitative studies were published, with one unpublished qualitative thesis. All were conducted in the northern hemisphere, though one explored experiences of international students studying abroad and receiving support for first-episode psychosis [Reference Lee, Marandola, Malla and Iyer35]. The quantitative studies recruited 78–200 majority male participants to observational cohort designs. The qualitative studies recruited 5–24 participants, with a broadly even male: female reported gender mix (though Cowan et al. [Reference Cowan, Pope, MacDonald, Malla, Ferrari and Iyer30] recruited more men). The majority utilized semi-structured interviews (n = 5) and thematic analyses (n = 4).

Key findings

The three quantitative studies examined care pathways to early intervention services to determine barriers to access, the role of stigma specifically, and potential differences with ethnicity (see Tables 5 and 6). Mental health stigma was identified a key barrier to seeking access to services and predicted DUP [Reference Kular, Perry, Brown, Gajwani, Jasini and Islam28]. Structural barriers within broader mental health services then delayed access to early intervention teams, thereby limiting the impact of these services on reducing DUP [Reference Birchwood, Connor, Lester, Patterson, Freemantle and Marshall17]. Perhaps unexpectedly, there were no differences in DUP or who initiated help-seeking (the person themselves, family/friends, or police) between ethnic groups, though Asian and other minoritized ethnic groups were more likely than White (×4) and Black (×3) participants to access early intervention via emergency services [Reference Archie, Akhtar-Danesh, Norman, Malla, Roy and Zipursky27].

Table 5. Study characteristics

a Five participants were excluded from analyses due to insufficient information to calculate DUP.

b N denotes a subset of the 132 participants in a wider study; demographic details describe the full sample.

Table 6. Key findings of the original studies

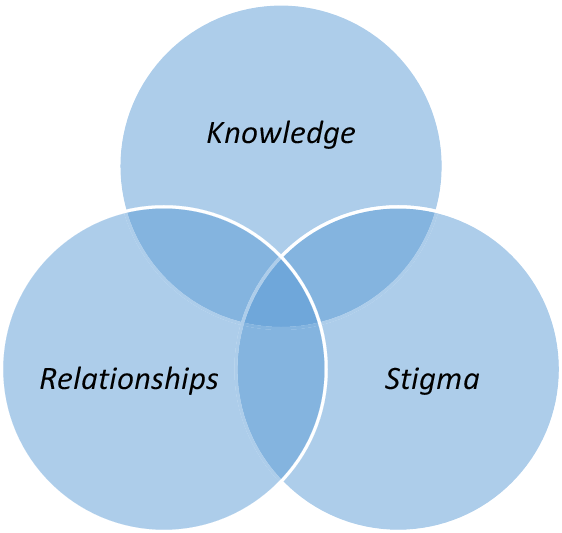

Thematic analysis of the qualitative data [Reference Booth, Noyes, Flemming, Gerhardus, Wahlster and Van Der Wilt36–Reference Noyes, Booth, Cargo, Flemming, Harden, Harris, Higgins, Thomas, Chandler, Cumpston, Li, Page and Welch38] yielded three descriptive themes associated with barriers and facilitators to accessing early intervention for psychosis services: knowledge, stigma, and relationships (see Table 6 and Supplementary Material).

Knowledge describes individuals’ experiences in which information (or absence of information) known to the person and their support system (including families and mental health professionals) had a critical impact on whether and when they were able to access early intervention services. All studies identified limited knowledge – whether regarding psychosis symptomology, possible trajectories, and treatment options – as a significant barrier to help-seeking. For example, misattribution of symptoms to depression, drug use, or normal experiences of adolescence [Reference Jansen, Wøldike, Haahr and Simonsen33], believing that symptoms did not warrant treatment [Reference Bay, Bjørnestad, Johannessen, Larsen and Joa29, Reference Harris31, Reference Jansen, Wøldike, Haahr and Simonsen33], and being unaware of services available [Reference Bay, Bjørnestad, Johannessen, Larsen and Joa29, Reference Islam, Rabiee and Singh32], all delayed help-seeking and therefore access to recommended treatments. When people did seek help, this lack of knowledge could be compounded by that of primary care clinicians (e.g., General Practitioners in the UK) who also misattributed symptoms to anxiety or depression [Reference Bay, Bjørnestad, Johannessen, Larsen and Joa29, Reference Islam, Rabiee and Singh32], and other relevant professionals (e.g., immigration officials for international students) [Reference Lee, Marandola, Malla and Iyer35].

By contrast, four studies highlighted the impact of accurate information about psychosis and mental health services, for example from ongoing public health campaigns, on facilitating access [Reference Bay, Bjørnestad, Johannessen, Larsen and Joa29–Reference Harris31, Reference Jansen, Wøldike, Haahr and Simonsen33], and that actively seeking additional information helped people develop an understanding of their experiences which in turn prompted help-seeking [Reference Harris31, Reference Jansen, Wøldike, Haahr and Simonsen33].

Stigma of mental health problems was identified in all qualitative studies as a key barrier to seeking access to early intervention services. Participants’ stigmatized beliefs about mental illness, and fears about others’ responses, in line with dominant societal discourses, affected the likelihood of disclosure and help-seeking [Reference Bay, Bjørnestad, Johannessen, Larsen and Joa29–Reference Harris31, Reference Jansen, Wøldike, Haahr and Simonsen33–Reference Lee, Marandola, Malla and Iyer35]. Two studies found that specific fears about being returned to hospital stopped people seeking help [Reference Harris31, Reference Jansen, Pedersen, Hastrup, Haahr and Simonsen34]. Socio-cultural factors affected stigma and therefore help-seeking and access to services. For example, where dominant narratives were highly stigmatizing of mental illness (and psychosis specifically) people were less likely to seek help from early intervention services [e.g., Reference Harris31, Reference Islam, Rabiee and Singh32].

The third descriptive theme highlights the impact of quality of relationships on likelihood of accessing early intervention services. Consistent emotional and practical support to disclose and manage psychotic experiences day-to-day increased access to services across six studies [Reference Cowan, Pope, MacDonald, Malla, Ferrari and Iyer30–Reference Lee, Marandola, Malla and Iyer35], and a lack of supportive familial relationships and friendships was identified as a barrier [Reference Harris31, Reference Lee, Marandola, Malla and Iyer35]. Similarly, collaborative relationships with interpersonally effective professionals that support autonomy and shared decision-making, and flexible service systems (e.g., regarding the pace of engagement), facilitated help-seeking and maintenance of early engagement with services [Reference Cowan, Pope, MacDonald, Malla, Ferrari and Iyer30–Reference Islam, Rabiee and Singh32; Reference Jansen, Pedersen, Hastrup, Haahr and Simonsen34]. Given the typical age of onset for psychosis, parental relationships were both a key facilitator and barrier [Reference Jansen, Wøldike, Haahr and Simonsen33, Reference Jansen, Pedersen, Hastrup, Haahr and Simonsen34].

The iterative process of thematic analysis, and discussion within the research team, highlighted links between the three themes - how knowledge, stigma, and relationships often intersect to facilitate or create barriers to accessing early intervention services. Interpreting the qualitative data across the primary studies yielded an overarching analytic theme of intersectional knowledge and beliefs about self and others, which represents the three overlapping themes and highlights the inherently interpersonal nature of stigma and relationships (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Intersectional knowledge and beliefs about self and others.

Knowledge and likelihood of accessing further information are affected by stigmatized beliefs about psychosis, mental health care, and oneself as a person who may have psychosis and need to access services. Generalized and self-stigma beliefs are by definition dependent on dominant socio-cultural discourses (e.g., psychosis as shameful) as well as personal and professional relationships. These generalized and specific social relationships in turn influence the knowledge we access and privilege when making healthcare decisions. The intersectionality of knowledge, stigma, and relationship beliefs about self and others suggests that public health and healthcare initiatives that target these in combination are likely to be more effective than strategies that focus on any one area in isolation.

Discussion

This is the first systematic review of the barriers and facilitators to accessing early intervention for psychosis services. A comprehensive search of the published and unpublished literature (with no date limits) yielded 10 papers, the majority of which were qualitative.

A recent review by O’Connell et al. [Reference O’Connell, O’Connor, McGrath, Vagge, Mockler and Jennings18] highlights factors likely to improve implementation of early intervention services. Our review complements this by identifying factors which influence whether people seek access to these services. Mental health stigma is a key barrier and predicts DUP. Structural service barriers then further delay access to specialist services, despite the introduction of access and waiting times standards [Reference Kreutzberg and Jacobs48]. A synthesis of the qualitative studies generated three themes which both hinder and facilitate access to services: knowledge, stigma, and relationships, and an overarching analytic theme of intersectional knowledge and beliefs about self and others.

These findings align with and extend the wider literature which suggests that limited knowledge about mental health delays access to services for people with psychosis [Reference Anderson, Fuhrer and Malla49, Reference Lal, Dell’Elce, Tucci, Fuhrer, Tamblyn and Malla50], and that mental health literacy alongside supportive social and professional relationships increases help-seeking, which may in turn reduce DUP and improve outcomes [Reference Upthegrove, Atulomah, Brunet and Chawla51]. Like McGonagle et al. [Reference McGonagle, Bucci, Varese, Raphael and Berry52], we found that stigma plays a key role in whether people disclose early psychosis and seek access to services, and that this is affected by dominant socio-cultural expectations [Reference Chatmon53]. Our review suggests that public health and service level initiatives should target these factors in integrated approaches that acknowledge the links between knowledge, stigma, and relationships.

Public health, service, and research implications

Mental health literacy campaigns (targeting knowledge) delivered in cultural context (to address culturally shaped stigma) and targeting local communities as a whole (to influence social and professional relationships) may be particularly effective. For example, healthcare in-reach to schools might strengthen the impact of accurate information about psychosis and treatment options by drawing on young people’s often strong and collective sense of social justice to challenge the shame that drives stigmatizing beliefs about psychosis [cf. Reference Svensson and Hansson54], and engaging well-regarded people in the local community to speak about their experiences of psychosis and accessing services – parent, child, and clinician triads might be particularly compelling.

Targeted training on the early signs of psychosis, how to access information and services, and how to be interpersonally effective in these interactions, should be delivered to professional groups who may come into contact with young people experiencing early signs of psychosis. Given the barriers identified in the current study, this should include primary care clinicians, emergency services, and education/immigration officials working with international students.

Secondary care services are likely to be more effective when clinicians are able to prioritize the development of supportive and trusting relationships with young people, shared decision-making, and flexible service delivery. These are of course built into service models for early intervention services, but are at risk when caseloads increase beyond recommended levels. The growing inclusion of peer support workers and befriending schemes in these teams is particularly welcome given the likely impact on knowledge, stigma, and relationships [Reference Repper, Aldridge, Gilfoyle, Gillard, Perkins and Rennison55–Reference Hansen, Bayford, Wood, Proctor, Jansen and Newman‐Taylor57]. Routine clinical practice within these services should be extended to include culturally sensitive exploration of self-stigmatizing beliefs, and modeling of alternative ways of understanding and responding to psychosis, as a means of securing tentative engagement with young people.

In terms of research, we now need longitudinal quantitative and qualitative studies of young people’s decision-making and behaviors from the first signs of at risk mental states, in order to examine the role of candidate individual, interpersonal and service-related factors that affect likelihood of seeking access to specialist services, and how these change and can be targeted over time.

Conclusion

This review identifies key barriers and facilitators to seeking access to early intervention for psychosis services, and complements a recent review of the barriers and facilitators to implementation of these services [Reference O’Connell, O’Connor, McGrath, Vagge, Mockler and Jennings18]. Together, these reviews highlight public health, systemic, service and staff factors that may be targeted to facilitate access to early intervention services, with the aim of reducing DUP and improving outcomes for people with psychosis.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2023.2465.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interest

The authors declare none.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.