Introduction

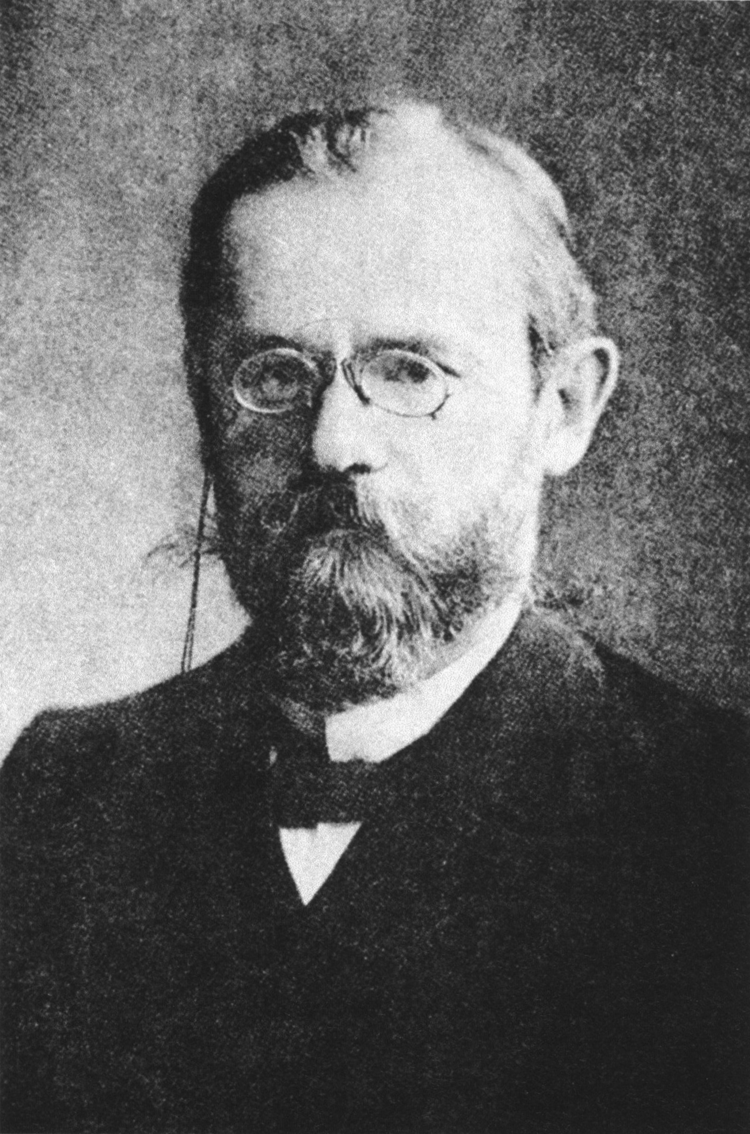

Théodore Macridy (1872–1940) was a leading Ottoman Greek archaeologist and museologist (Figure 1) whose life and career spanned the Ottoman Empire, republican Turkey, and modern Greece. He was one of the pioneers of Ottoman archaeology, directing or participating in Western European archaeological missions in locations as diverse as Baalbek, Ephesus, Hattuša, Sidon, and Thessaloniki. Apart from his excavation activities, Macridy emerged as a leading museum curator and maintained a rich and diverse publication record. He was active during the tumultuous period of the 1910s and 1920s in the Ottoman Empire and republican Turkey. Following his retirement and the 1929–1930 rapprochement in Greek-Turkish relations, he accepted an invitation to become the founding director of the Benaki Museum in Athens.

Figure 1. Théodore Macridy (1872–1940).

(Source: Public Domain, Wikimedia Commons Licence.)

This study explores the transfer of knowledge in archaeology and museology from the West to the Ottoman Empire, Turkey, and Greece through the life and career of Macridy. He was active in more than one field and in more than one country. His multi-layered identity as an Ottoman citizen of Greek origin, his excavation of multiple sites in the Ottoman Empire, his curatorial work at the Ottoman Imperial Museum, and the foundation of the Benaki Museum in Athens at the end of a long career identify him as a ‘liminal scientist’ whose cosmopolitan identity led to his relative neglect in both Greek and Turkish national archaeology and museology (Thomassen, Reference Thomassen2009; Beech, Reference Beech2011).

More than fifty years ago, in his influential article on the spread of Western science, Basalla (Reference Basalla1967) suggested a model for the proliferation of Western science throughout the non-Western world. He identified three phases: discovery, the emergence of ‘colonial science', and the advent of ‘national science'. The use of the term ‘colonial’ did not necessarily mean a colonial relationship between a European state and a non-European territory: it referred to the discrepancy in Western science, which was meant to be filled through the three-stage model suggested. Basalla's classification focused on the emergence of the ‘colonial scientist’, i.e. a scientist who may have been born in Western Europe or may have been a local individual acting as a vector of Western science. By mediating between the West and their homeland, they paved the way for the eventual rise of a national scientific tradition. The local ‘colonial scientist’ remained distinct from Western scientists because of their nationality, education, and normative background. Education and willingness to embrace Western knowledge and norms would also have distinguished this scientist from other compatriots.

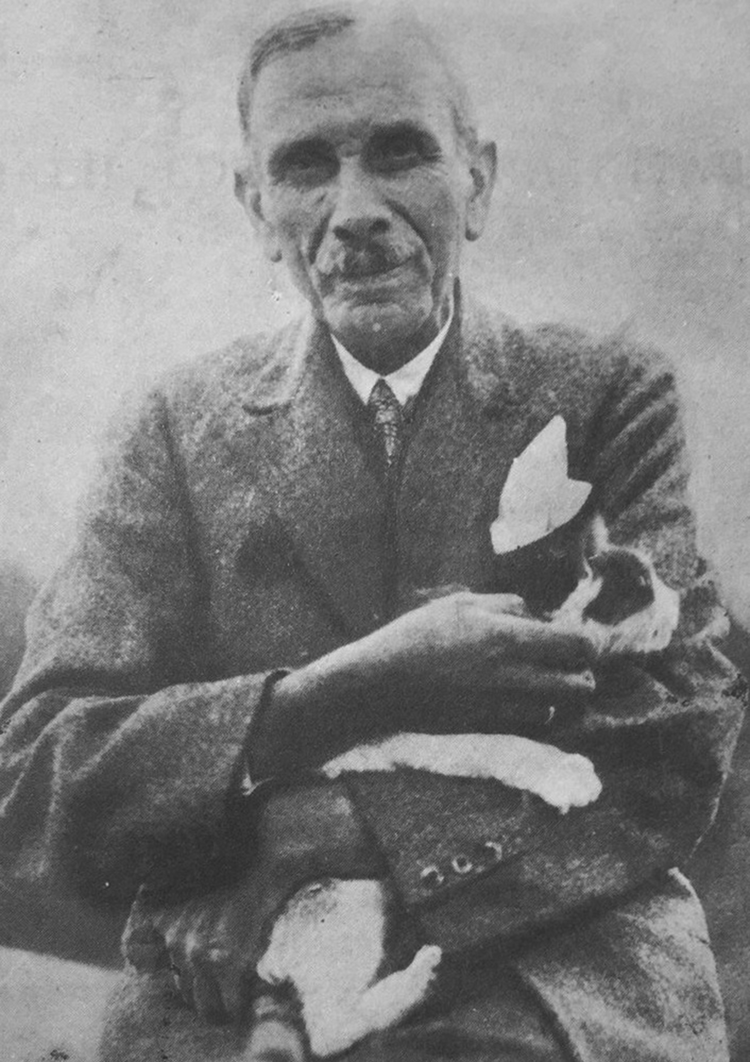

The rise of postcolonial critique of the history of science has questioned Basalla's model and exposed its shortcomings (MacLeod, Reference MacLeod1980: 4–7; Inkster, Reference Inkster1985: 680–84; Raj, Reference Raj2013: 339–40). Krishna suggested a new classification of scientists involved in the introduction of Western science in the Orient, as ‘gate keepers’, ‘scientific soldiers’, and ‘national’ scientists (Krishna, Reference Krishna, Petitjean, Jami and Moulin1992: 57–60). Macridy's case sheds some new light on the complexities of Western scientific transfer to the Ottoman Empire which the Basalla model cannot successfully address. Macridy does not fit into any of the suggested classifications. He was not born in a Western European country like the German director of the Ottoman Imperial Museum Philipp Anton Dethier, or the German archaeologist Hugo Winckler (Figure 2). He did not study at a renowned university in western or central Europe like his fellow Ottoman Greek archaeologist Vassileios Mystakides. Unlike the latter, he abstained from embracing Greek nationalism and Orthodox Christianity and remained secular and loyal to his bureaucratic duties and the ailing Empire. Adding to his surname the honorific suffix ‘Bey', unusual for an Ottoman Greek, he remained a champion of Ottomanism while opposing minority nationalisms were booming and eventually contributed to the demise of the Empire. His education was completed in Istanbul, and there is no record of professional trips to western and central Europe. On the other hand, the local institutions where he was educated were beacons of Westernization serving to introduce Western science and ideologies to the Ottoman Empire. Moreover, his duties and his desire to apprentice with accomplished German archaeologists such as Winckler and Puchstein, as well as local archaeologists such as Baltazzi, allowed him to learn from observation and participation and emerge as one of the leading archaeologists and museologists of the late Ottoman era.

Figure 2. Hugo Winckler (1863–1913).

(Source: Public Domain, Wikimedia Commons Licence.)

Failing to fit in any nationalist narrative, Macridy's work and contribution has remained unacknowledged. He is rarely mentioned together with the founding fathers of Ottoman archaeology and museology, Osman Hamdi (Figure 3) and Halil Edhem (Figure 4), despite his close collaboration with both. This reflects a general trend, in which the role of non-Muslims in the introduction and establishment of Western science to the Ottoman Empire has been traditionally underplayed. History became compartmentalized and fragmented into national narratives, where the role of those actors who failed to fulfil the definition of national narrative goals went underreported or even unnoticed (Eldem, Reference Eldem2013: 274–75). Meanwhile, the contribution of foreign archaeological missions to the development of archaeology and museology in the Ottoman Empire remains highly contested (Tütüncü Çağlar, Reference Tütüncü Çağlar2017b: 112–18). The official republican Turkish narrative aimed to downplay, if not eliminate, the contribution of Western archaeologists in the establishment of the first Ottoman museum, the Ottoman Imperial Museum, and the introduction of archaeology and museology. Their role was either ignored or reduced to that of plunderers profiteering from the local cultural heritage and the ignorance or complicity of the local authorities. In Greece, too, Macridy's work and contribution have gone mostly unnoticed, despite his numerous excavations at Classical, Hellenistic, Roman, and Byzantine archaeological sites, including sites located today within the borders of Greece. Even his contribution as founding director and author of the first catalogue of the Benaki Museum has not been fully recognized. Thus, studying Macridy's life becomes an opportunity to explore the contribution of non-Muslims to the introduction of science and ideas and to the establishment of archaeology and museology in the late Ottoman Empire.

Figure 3. Osman Hamdi (1842–1910).

(Source: Public Domain, Wikimedia Commons Licence.)

Figure 4. Halil Edhem [Eldem] (1861–1938).

(Source: Public Domain, Wikimedia Commons Licence.)

Macridy's Life and Career Before Athens

Théodore Macridy was born in the Abdi Subaşı district of the Phanar (Fener) neighbourhood of Istanbul in 1872. He was the son of Constantine ‘Ferik’ Macridy Paşa, a military doctor who rose to the rank of Brigadier General. The family's origins were said to be in Ottoman Macedonia, in the village of Belatch (Blatzi, present-day Vlasti, Greece) near the town of Soroviçe (Sorovich, present-day Amyntaion, Greece). Macridy attended the leading Ottoman Greek educational institution, the Phanar Greek High School. In 1884, he entered the Galatasaray Imperial School. This choice signalled a priority that differed from that of other students of the Phanar Greek High School. Instead of continuing his studies there with the aim of moving to university in Athens or a western or central European city, He made a choice that could help him pursue a career in the Ottoman bureaucracy. He graduated from the Galatasaray in 1889 and started working in 1890 for the Ottoman Public Debt Administration (Düyun-ı Umumiye, in the Société de la régie co-intéressée des tabacs de l'empire Ottoman). On 1 April 1892, at the age of twenty, he was appointed as secretary (kâtip) to the French Language Secretariat of the Ottoman Imperial Museum (Müze-i Hümayun) (Ogan, Reference Ogan1941). Appointed three months before the vice director of the Museum, Halil Edhem, Macridy developed a close relationship with the latter. While Edhem was ten years older than Macridy and spent much of his early life in western and central Europe, both started working at the museum at the same time, retired at almost the same time thirty-eight years later and died within a few months of each other.

The personal relationship of Macridy's father, Constantine Macridy Paşa, with Osman Hamdi and Demosthène Baltazzi probably played a role in his appointment. Macridy Paşa was an avid collector of Byzantine coins (Macridy Pacha, Reference Pacha1887), who presided over the museum's numismatics committee and sold his personal collection of 1214 Byzantine coins to the Imperial Museum at a nominal price (Cinoğlu, Reference Cinoğlu2002: 5–6). The young secretary developed a keen interest and inclination in archaeology (Ogan, Reference Ogan1941: 163). Macridy's interests soon went beyond his clerical duties as he started serving as an apprentice to established museum archaeologists such as Demosthène Baltazzi, one of the first Ottoman archaeologists and a senior member of the Ottoman Imperial Museum administration. Baltazzi, who belonged to a leading Greek-Levantine family in Izmir, engaged in archaeological activities as early as the mid-nineteenth century and was invited to help with the establishment and organization of the Imperial Museum. Macridy helped Baltazzi identify, classify, and record the moveable archaeological items shipped to the museum from provincial authorities.

Following his in-museum apprenticeship under Baltazzi and while maintaining his position as French secretary, Macridy—apparently on Osman Hamdi's advice—started undertaking new duties. He occasionally guided and escorted foreign delegations or significant visitors to the museum. More importantly, as a representative of the Ottoman Imperial Museum, Macridy became a commissioner in excavations organized on behalf of the Ottoman Imperial Museum by foreign missions. While the government appointed local officials as commissioners in excavations of lesser importance, the museum sent its own personnel to more important investigations. Macridy was responsible for facilitating the excavation from a logistics perspective and for ensuring that the Ottoman legislation on antiquities was observed: the share of artefacts belonging to the Ottoman state would be shipped to Istanbul for display in the new halls, which Osman Hamdi was planning to have built. Macridy's position required knowledge of several European, ancient, and local languages, bureaucratic competence, and interpersonal skills. The fact that he was assigned to the most important excavations demonstrate his abilities and the trust that Osman Hamdi and Halil Edhem had in him.

Such duties offered excellent opportunities. Given his keen interest in archaeology, Macridy seized the chance to learn from some of the most prominent archaeologists of his time. His first duty as a commissioner was on the excavations of the Austrian archaeological mission under Otto Benndorf in Ephesus (Ayasoluk) in 1897. Macridy attended these excavations several times in 1898, 1902–1903, and 1905–1906. In 1898 he also visited the German excavations of Priene and Miletus. Moreover, Macridy was assigned to serve as commissioner in the German excavations conducted by Otto Puchstein in Baalbek and Palmyra in 1900–1902 and Sidon in 1902 (Ogan, Reference Ogan1941: 164–66; Cinoğlu, Reference Cinoğlu2002: 7). In light of his progress, Osman Hamdi entrusted Macridy, ten years after he entered the museum service, with the management of an excavation of his own. Macridy's first excavation was in Sidon, which Osman Hamdi himself had excavated in the 1880s, when he (Osman Hamdi) discovered the sarcophagi that brought world acclaim to him and the Ottoman Imperial Museum. The accidental discovery of important antiquities in Sidon and the fear that any delay in organizing an excavation would lead to looting by local antiquity smugglers made Osman Hamdi assign the task to Macridy in 1902. As commissioner, Macridy was already familiar with Sidon and its archaeological site. His own excavation gave him the opportunity for his first academic publication as an archaeologist (Macridy, Reference Macridy1902). While successfully continuing his excavation in Sidon between 1902 and 1905 (Macridy, Reference Macridy1903, Reference Macridy1904a, Reference Macridy1904b), Macridy was asked to conduct excavations in Raqqa. His work in the ruins of the Abbasid palace led to the discovery of important artefacts of Islamic pottery, which were shipped to the Imperial Museum (Tütüncü Çağlar, Reference Tütüncü Çağlar2017a: 114–25).

The project that bestowed fame on Macridy was the 1906–1907 and 1911–1912 excavations at Boğazköy near the central Anatolian town of Çorum (Schachner, Reference Schachner, Doğan-Alparslan, Schachner and Alparslan2017: 42–50, 58–66). As commissioner of the excavation led by the German archaeologist Hugo Winckler, Macridy's activities soon went beyond those of a commissioner, and he became involved in the operation of the excavation under Winckler's supervision. He took part in discovering the ruins of Hattuša and the tablets which led to the decipherment of the Hittite language, including those outlining the Treaty of Kadesh between the Hittites and the Egyptians. The cuneiform tablets were deciphered about a decade after their discovery by the Czech Orientalist Bedřich Hrozný, whose achievement was a significant breakthrough and confirmed that the Hittite language belonged to the Indo-European language group (Beckman, Reference Beckman1996: 27– 28). As his private correspondence with Halil Edhem shows (published in Eldem, Reference Eldem, Doğan-Alparslan, Schachner and Alparslan2017: 163–68), he tried to convince his supervisor that his contribution lay far beyond a commissioner's duties and that his excavations produced more findings than those of the members of the German team; he was, however, apparently not given permission to publish any of the archaeological findings in Boğazköy. Macridy's diverse skills were recognized by Winckler, who asked the Ottoman Imperial Museum that Macridy be assigned again to his excavation as a commissioner, citing the latter's exceptional administrative aptitude and stating his gratitude for his contribution to his excavation. Osman Hamdi approved Winckler's request. Macridy's career was taking off, and his fieldwork led to the production of further publications. In 1907, he moved from his post as French secretary to that of conservator, and his salary rose accordingly. Macridy entered the most prolific period of his life. He spent an increasing part of his time in excavations throughout the Ottoman Empire, maintaining a diverse research programme with remarkable dynamism and stamina. This required travelling and living a quasi-nomadic life under the inevitably harsh conditions of the time, encountering infectious diseases, hygiene problems, and severe weather, as well as issues with local authorities. Macridy also appreciated nature, a necessity in an archaeologist's life at the turn of the twentieth century. In one of his reports on the excavation of the Akalan castle near Samsun, Macridy mentioned his regret at having to destroy the vegetation covering the ruins of the site (Cinoğlu, Reference Cinoğlu2002: 8).

Macridy also kept up with his bureaucratic duties in Istanbul. While the number of artefacts arriving at the museum was constantly rising, the decision to transport the sarcophagi discovered by Osman Hamdi from Sidon to Istanbul made the erection of a new museum building necessary. Osman Hamdi commissioned Alexandre Vallaury, architect and teacher at the School of Fine Arts (Sanayi-i Nefise Mektebi) to design a new museum building inspired by one of the Sidon sarcophagi. It was inaugurated in 1891 and hosted the sarcophagi. Macridy developed an expertise in organizing the secure transport of antiquities to Istanbul, packaging them carefully and transporting them safely by railway or sea. Given the artefacts’ fragility and the poor transport infrastructure of the times, artefacts were often damaged during their transport to the Ottoman capital.

As new extensions were added to the museum in 1902 and 1908, a decision was made to dedicate the Çinili Köşk (one of the Imperial Museum buildings in Istanbul) exclusively to Islamic artefacts. Moving the museum items to their new home, classifying them, and organizing the Islamic art museum collection was a formidable task. While improving his curatorial skills, Macridy engaged in an intensive excavation schedule despite the museum's limited resources. In 1897 and 1904 he conducted excavations in Notion, Claros, and Colophon on the Ionian coast (Macridy, Reference Macridy1905). In 1907 he conducted excavations at Alacahöyük near Çorum, where he discovered the Sphinx Gate (Macridy, Reference Macridy1908) at Akalan, an unidentified fortified site near the city of Samsun (Amissos) on the Black Sea coast (Macridy-Bey, Reference Macridy-Bey1907). In 1909, he undertook excavations in a sanctuary of Artemis on the Aegean island of Thassos (Macridy, Reference Macridy1912b). In 1910, he continued his excavations in Notion (Macridy, Reference Macridy1912a) and excavated a Hellenistic tomb—known today as the ‘Tomb of Macridy Bey’ and restored together with its adjacent funerary monuments in 2017—near the town of Langaza (Langadas) (Macridy, Reference Macridy1911), in the outskirts of Thessaloniki. The tomb's marble door and moveable items were transferred to the Imperial Museum. On 24 February 1910 Macridy's supervisor and patron Osman Hamdi died, following a career dedicated to the promotion of archaeology and museology in the Ottoman Empire. He was succeeded by his younger brother and vice director of the Ottoman Imperial Museum, Halil Edhem, with whom Macridy had been long acquainted.

Still in 1910, Macridy expanded his archaeological interests by excavating a Byzantine site, the ruins of Hebdomon in Makrıköy/Bakırköy, the Istanbul suburb where he resided (Macridy, Reference Macridy1938). In 1911, he visited the ruins of Troy and the excavations of Knidos, and excavated Daskyleion on the southern coast of the Marmara Sea (Macridy-Bey, Reference Macridy-Bey1913) while investigating the possibility of opening a new museum in the town of Biga (Bayram, Reference Bayram2018: 7). The outbreak of the Balkan Wars in 1912 and the First World War in 1914 inevitably limited Macridy's mobility and the availability of museum funds. Eventually, Macridy shifted his attention to excavation projects in Istanbul and its vicinity. In 1913 he and Charles Picard excavated the site of the Apollo Clarios sanctuary between Colophon and Notion on the Ionian coast (Picard & Macridy-Bey, Reference Picard and Macridy-Bey1915), conducted excavations in Sidon with Georges Contenau, and dug at Alacahöyük. In 1914 and 1916 he continued his excavations in the Hebdomon hypogeum in Bakırköy (Macridy & Ebersold, Reference Macridy and Ebersold1922: 363–93). As the First World War was raging, Macridy focused on his curatorial duties. Meanwhile, he suffered a family tragedy: the death of his son, who had been enlisted in the Ottoman army, in the Baghdad front devastated him, leaving a life-long wound and probably affecting his productivity (Ogan, Reference Ogan1941: 168).

After the First World War, in 1919, Macridy was appointed to the Office of Classification of Ancient Objects (Asar-ı Atika Tasnif Memurluğu) with an increased salary. In 1921 he published his first piece of research with Charles Picard after many years on ancient Cyzicus, near Erdek, on the Bithynian coast of the Marmara Sea (Picard & Macridy-Bey, Reference Picard and Macridy-Bey1921). Later, he also became an expert of Roman, Byzantine, and ancient Greek arts. Macridy remained in his post throughout the Greek-Turkish war of 1919–1922 and Istanbul's Allied occupation. In 1921 he participated in the excavations of the French archaeological mission in Istanbul (Macridy & Ebersold, Reference Macridy and Ebersold1922: 363–93), particularly at the Golden Gate at Yedikule (Macridy & Casson, Reference Macridy and Casson1923) and at Seddülbahir in the Dardanelles, where they excavated the so-called ‘tumulus of Protesilaus’ (Demangel et al., Reference Demangel, Macridy-Bey, Mamboury and Massoul1926). Following the victory of the Turkish nationalist forces in Anatolia and the end of Istanbul's Allied occupation, Macridy faced a disciplinary investigation by the new Kemalist administration. As he was found not to have cooperated with the occupation forces nor involved in any anti-Turkish activities between 1918 and 1923, his position at the museum was confirmed in January 1923.

Between 1924 and his retirement from the Istanbul Archaeological Museums, Macridy continued his excavations in Istanbul and undertook various curatorial duties in the museum, particularly regarding the Islamic art collection. In 1925, he conducted the first excavation in republican Turkish history, exploring the Ankara railway station's tumuli (Macridy, Reference Macridy1926a). He also took part in discussions about the conservation of Ankara's cultural heritage and the establishment of museums planned for Turkey's new capital (Macridy & Casson, Reference Macridy and Casson1931). In the same year, he excavated the Monastery of Constantine Lips (Fenari İsa Camii) in Istanbul (Macridy, Reference Macridy1964; Macridy et al., Reference Macridy, Mango, Megaw and Hawkins1964). In 1926 his excavations focused on the Hippodrome, the Golden Gate, and the Monastery of Myrelaion (Bodrum Camii) in Istanbul (Macridy & Casson, Reference Macridy and Casson1931). In 1927 he participated in the excavation of Joshua's Hill (Yûşa Tepesi) at Beykoz on the Anatolian side of the Bosporus. In 1928 he excavated the Forum of Theodosius (Forum Tauri) at Simkeşhanı in the Istanbul neighbourhood of Koska, opposite the Beyazıt Square. In parallel to his excavation activities, Macridy concentrated in the late 1920s on the organization and arrangement of the Islamic art collections at the Çinili Köşk.

Macridy in Athens: The Benaki Museum

Towards the end of his career, and benefiting from the Greek-Turkish rapprochement, which was underscored by the signature of the 1929–1930 Ankara Agreements, Macridy embarked on a flagship project that highlighted his unique expertise and contribution to the development of museology on an international level. After thirty-eight years of service, in November 1930 he retired from the Istanbul Archaeological Museums and, following permission from the Turkish government, moved to Athens. He was invited there by the Benakis family, one of Greece's leading business diaspora families based in Alexandria and who had amassed enormous wealth in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Emmanuel Benakis was one of Greece's leading benefactors, and his son, Antonios Benakis, decided to establish a museum in Athens to host his art collection. This collection included eastern Mediterranean and Chinese artefacts dating from antiquity to the nineteenth century.

The diversity of the collection made the job of finding a director difficult. Not only did the director need to possess experience and skills in museum administration and in organizing collections, but also had to have solid curatorial experience and knowledge not only of ancient Greek, Roman, and Byzantine art but also of Mesopotamian, Arabic, Ottoman, and Far Eastern art (in 2005 the extensive Islamic art collection moved to a separate branch). This rendered Macridy an ideal, and probably unique, candidate. In addition, his decade-long experience in the administration of the Ottoman Imperial Museum (later renamed the Istanbul Archaeological Museums) meant that he would be an excellent founding director of the new museum. He was one of the very few archaeologists and curators whose knowledge ranged from Mesopotamian civilizations to the Ottoman era. He was uniquely poised to evaluate and organize the diverse art collection of Benakis and turn it into one of the most important museums in Athens. Macridy worked as the founding director of the Benaki Museum from 1931 until his death in 1940.

This was the first time in his career that Macridy became a director, with complete freedom to apply the knowledge he had accumulated. Thanks to the Benakis family, he had ample resources and access to the most advanced techniques of the time. His unique combination of administrative and curatorial skills proved vital. He took personal interest in virtually all organizational aspects of the new museum (Macridy, Reference Macridy1937), including restoration, classification, arrangement, organization, lighting, security, heating, inventory making, personnel policy, and exhibition techniques. He examined and classified the artefacts, and he organized the exhibition halls and the museum collection using innovative methods. He displayed old textiles inside open old chests and used mirrors behind the artefacts to give visitors a better understanding of them. Macridy published the first museum catalogue in 1936 in English, German, Greek, and French. It included information comparing artefacts in the museum collection, identifying and explaining their artistic features. He also supervised the preparation of inventories listing all information about the exhibited artefacts. In addition, he developed the museum library and made sure that all books relevant to research were acquired. The Benaki Museum quickly became one of Athens’ leading museums, attracting international attention and acclaim.

Macridy maintained an active research agenda while in Athens. He completed the publication of his research on the Hebdomon (Macridy, Reference Macridy1938, Reference Macridy1939). He also conducted an extensive study of the textiles of the Benaki collection (Talbot Rice, Reference Talbot Rice1951), collaborating with Tahsin Öz, staff member of the Istanbul Archaeological Museums. Macridy's death and the outbreak of the Second World War delayed the publication of their work, which was published by Öz as a two-volume book on Turkish textiles and velvets (Öz, Reference Öz1946, Reference Öz1951).

While in Athens, Macridy did not sever his links with Istanbul and republican Turkish archaeology. He frequently travelled to Istanbul and visited excavations in and around the city. Towards the end of his life, he paid a visit to the archaeological excavations at Küçükçekmece (Rhegion). A few weeks later, Macridy fell ill and passed away in Istanbul in December 1940. As his family was in Athens during his illness, and Greece had entered the Second World War, his funeral was organized by his former colleagues at the museum. The funeral took place at the Greek Orthodox church of Bakırköy and was attended by representatives of the Istanbul Archaeological Museums, the Turkish Ministry of Education, the Topkapı Saray Museum, and the German Archaeological Institute (Ogan, Reference Ogan1941: 168–69). He was buried in the Greek Orthodox cemetery of Bakırköy, in the tomb of his father.

Macridy as an Ottoman Greek Bureaucrat

Théodore Macridy dedicated his life to the study of antiquity, mainly in the service of the Ottoman Empire, but also republican Turkey and Greece. His life and career could be considered a textbook case of Ottomanism, the Ottoman civic nationalism, aiming to include all Ottoman citizens, regardless of their religious and ethnic origins (Grigoriadis, Reference Grigoriadis2007: 424). His father's decision to have him educated in both leading Ottoman educational institutions, one Greek and one Turkish, indicates his ideological orientation. Following the example of his father, who became an Ottoman general, he entered Ottoman bureaucracy and this position became the defining element of his identity. Remarkably, he found it appropriate to add the Ottoman honorific title ‘Bey', a courtesy title for the sons of a ‘pasha’, to his surname. Being the son of an Ottoman pasha was something that made him feel pride. Indeed, Macridy felt so comfortable with the title that the suffix ‘Bey’ appeared in several of his academic publications. This is harder to understand today, given that the integration of Ottoman Greeks to the Ottoman administration has been underplayed in nationalist historiographies, both Greek and Turkish.

Macridy's personal correspondence with Halil Edhem Bey, his supervisor at the Ottoman Imperial Museum, published by the latter's grandson Edhem Eldem (Eldem, Reference Eldem, Doğan-Alparslan, Schachner and Alparslan2017) gives us a better grasp of Macridy's identity. One of the most telling dimensions of their relationship was their correspondence in French. While they could correspond in Ottoman Turkish, in which Macridy was fluent, they preferred to correspond in French, the language of instruction in the school where they both studied. French became their common intellectual and academic milieu. This language symbolized the modernization of the Ottoman Empire which distanced them from their Ottoman Turkish and Greek linguistic backgrounds and established them on a common ground (Eldem, Reference Eldem, Doğan-Alparslan, Schachner and Alparslan2017: 171–73). It also symbolized a robust bond between an Ottoman Turkish and an Ottoman Greek bureaucrat who worked hard to establish two Western disciplines in the Ottoman Empire by helping found the Ottoman Imperial Museum and organizing its activities.

In his correspondence with Halil Edhem, Macridy occasionally referred to his fellow Ottoman Greek archaeologist Vassileios Mystakides, a senior colleague of his at the Ottoman Imperial Museum in ways that shed light on his own identity (Eldem, Reference Eldem2010: 29–30). Mystakides’ career offers intriguing parallels and contrasts to that of Macridy. He was also born in Istanbul in the suburb of Kumkapı (Kontoskalion) and studied in the Phanar Greek High School. Unlike Macridy, however, he continued his studies not at the Galatasaray Imperial School but at the University of Athens. From Athens, Mystakides moved to Germany and the University of Tübingen, where he acquired a doctorate. Starting his professional career as director of Greek high schools in Filibe (Plovdiv in present-day Bulgaria) and Kayseri (in present-day Turkey), Mystakides was offered a position at the Ottoman Imperial Museum by Osman Hamdi and eventually became the director of the museum library. Like Macridy, he also served as a commissioner in excavations organized by the Ottoman authorities in collaboration with foreign archaeological schools; he also kept a teaching position at the Phanar Greek High School, the most prominent educational institution of the Ottoman Greek community, where he taught geography and history.

In contrast to Macridy, who had no professional or informal connections to Greek Orthodox minority institutions, Mystakides was socially conservative and closer to the Orthodox Church. Although born in the Phanar neighbourhood where the Ecumenical Patriarchate has been based since the early seventeenth century, Macridy maintained a distinctly secular attitude and did not appear to be actively involved in the community affairs of the Ottoman Greek millet. His distance from Orthodox observance and ‘Ottoman Greek manners’, which he considered no less ‘Oriental’ than the ‘Ottoman Turkish’ ones, emerged clearly in sarcastic comments. While describing how he became surrounded by Catholic priests in Baalbek, he added that, with this entourage, ‘he could be competing with Mystakides and his priests’ (Eldem, Reference Eldem2010: 30). Writing to Halil Edhem that he worked on an Easter Day at the Boğazköy excavation, he added that, had his ‘friend’ Mystakides heard about it, he would have him excommunicated (Eldem, Reference Eldem, Doğan-Alparslan, Schachner and Alparslan2017: 173–74). And while describing a Hittite vase decorated with a cross-like motif, he noted that his ‘friend’ Mystakides would have considered it a blasphemy to think of the existence of the cross before Jesus Christ (Eldem, Reference Eldem, Doğan-Alparslan, Schachner and Alparslan2017: 173–74). Finally, while upset with the meddlesome attitude of one of the local officials and the latter's letter to the Çorum provincial governor about his work, he referred to his manoeuvring not as ‘alaturka’ or Oriental but as ‘disgusting’ and ‘Mystakides-like’ (Eldem, Reference Eldem, Doğan-Alparslan, Schachner and Alparslan2017: 173–74), as opposed to the Western ‘alafranga' side, which he saw himself and Halil Edhem as representing. Millet affiliations did not matter in that respect, but values, manners, and attitudes did. Macridy implied that his secular lifestyle and Western values connected him to Halil Edhem more strongly than his millet-based connections with Mystakides.

Macridy’ s loyalty to the Ottoman Imperial Museum and the Ottoman Empire manifested in several instances. In his capacity as commissioner, he did his best to ensure that the museum remained in control of the excavations despite its administrative weakness. In one of his letters to Halil Edhem, he stated: ‘Contrary to what some may think, we should not give the impression that the excavation is executed by an institution other than the Museum’ (Eldem, Reference Eldem, Doğan-Alparslan, Schachner and Alparslan2017: 169).

Macridy took special care that all artefacts were safely transported to the Ottoman Imperial Museum, doing the same for findings from archaeological sites that later shifted from Ottoman to Greek sovereignty. He was responsible for the transport of an early Byzantine pulpit from the Hagia Sophia church (then Ayasofya mosque) in Thessaloniki. He also transferred to the Imperial Museum the marble door and the moveable finds of the Hellenistic tomb he excavated near the town of Langadas (Langaza) in the outskirts of Thessaloniki. These artefacts still belong to the collection of the Istanbul Archaeological Museums.

As mentioned, the loss of his son was devastating for Macridy. The question of the participation of non-Muslims in the Ottoman army has remained a controversial issue, as it debunked republican Turkish nationalist narratives about the role of non-Muslims in the demise of the Ottoman Empire. Despite his son's service, Macridy had to undergo an investigation of his national convictions at the end of the 1919–1923 Greek-Turkish war. Working hard to protect the Ottoman interests and enrich the Imperial Museum's collection and being the father of an Ottoman Greek soldier fallen in combat was apparently not enough to signal his loyalty to the Ottoman Empire and republican Turkey.

His sentiments toward Ottoman state institutions came to the fore again in 1934 (Cinoğlu, Reference Cinoğlu2002: 9). Following Atatürk's reforms and the introduction of the Latin alphabet, a large part of the Ottoman archives was thrown away or put on sale. Soon, crucial primary and secondary Ottoman historical sources appeared on the market within Turkey and abroad. When the new Turkish ambassador to Greece, Ruşen Eşref Ünaydın, arrived in Athens, Macridy visited him and invited him to dinner (Cinoğlu, Reference Cinoğlu2002: 9–10). During the dinner, the ambassador noticed some large binders in the room. When asked about them, Macridy responded that the goal of the invitation was to show these. The ambassador soon realized that these contained essential archival material from the Topkapı Palace Archive. Macridy confirmed this and added with regret:

Mr. Ambassador, the worst is that these binders were put on sale by my successors. These documents are brought to display from embassy to embassy in Athens. Interested embassies can buy the document they find useful. (Cinoğlu, Reference Cinoğlu2002: 9–10)

Macridy could not bear the loss of these valuable testimonies of Ottoman history. So, when they were shown to him, he requested to keep them to alert the Turkish ambassador in case he was interested in buying them. Ünaydın told Macridy to keep the documents and that he would consult with Ankara about their purchase. As Ankara was slow to answer, Ünaydın decided to purchase the binders himself (Cinoğlu, Reference Cinoğlu2002: 9–10). Decades later, on 1 May 1956, he donated the documents to the Topkapı Palace Museum, mentioning Macridy and the story of their purchase (Cinoğlu, Reference Cinoğlu2002: 9–10). This was ample illustration of Macridy's concern about the state of the institutions he served for most of his career and the historic and cultural loss that the destruction of the Ottoman Archives entailed. Contrary to what his colleague and partner Picard (Reference Picard1944: 48) wrote in his obituary, where he stressed Macridy's Greek identity as a natural reason for his interest in archaeology and ancient civilizations, Macridy's ethnic and religious background was not the driving force behind his passion for archaeology and museology. Macridy cared for Hittite, Phoenician, Greek, Roman, Abbasid, and Ottoman heritage, without political calculations.

Macridy as a ‘Liminal Scientist'

Macridy's life spanned the Ottoman Empire, Turkey, and Greece, and, while he never lived in western or central Europe, his research was published and recognized across the West, appearing in leading academic journals throughout Europe. He cannot be classified as a ‘colonial scientist’ since he was not educated in one of the leading western and central European countries, unlike Halil Edhem or Vassileios Mystakides. He never received training in archaeology or history in one of Europe's leading academic institutions with the aim to transfer the knowledge acquired back to the Ottoman Empire. Unlike many Istanbul Greeks of his time, he did not study at the University of Athens, the first university established in south-eastern Europe in 1837, whose aim it was to serve as a model for the promulgation of Western ideas and knowledge. His education was limited to two of the most prominent educational institutions of the Ottoman capital: the Phanar Greek High School, arguably the first educational institution of the Ottoman Empire serving since the seventeenth century as the entry point of Western scientific knowledge, and the Galatasaray High School, one of the flagship institutions of the Tanzimat (the reformist era of the Ottoman Empire) and best suited to help Macridy pursue a career in the Ottoman administration. The foundation of the Galatasaray High School was meant to symbolize Ottoman reform, facilitate the bridging of deep-seated divisions, and promote the emergence of an Ottoman bourgeoisie committed to the defence of a Westernizing Empire's interests.

Macridy's means of acquiring his knowledge of archaeology and museology are inherently linked with the introduction and establishment of archaeology and museology in the Ottoman Empire. As Osman Hamdi's plans for establishing an Ottoman School of Archaeology never materialized, Macridy could only rely on acquiring knowledge through apprenticeships while performing his administrative duties. His work alongside Baltazzi, Winckler, and Puchstein gave him the chance to acquire valuable applied knowledge. Soon Macridy saw himself as more than a facilitator of the excavations of foreign archaeological missions in the Ottoman Empire. Through his command of the history of the Ottoman lands, his instinct, his indefatigable spirit and stamina, he claimed the duties and gained the titles of archaeologist and museologist.

It would be hard to identify Macridy with the emergence of a single national scientific tradition. Although he defined himself as an Ottoman archaeologist and museologist for most of his career, he put significant efforts into the establishment of Greek and Turkish museology. In the mid-1920s Macridy was involved in urban planning discussions about the new capital of republican Turkey, Ankara. At the Ministry of National Education's request, he prepared a report on the conservation and protection of historic monuments during the construction of Ankara, pointing out that ‘historical monuments are the most precious ornament of a city. In the countries where such monuments are absent, they observe with awe and envy’. He noted that the Americans built a replica of the Pergamon temple, and that in Switzerland a competition about the reconstruction of the Pergamon ruins was being organized. He concluded by stating that ‘our home country hosts the most excellent of these antique sites, and our duty is only to protect these’ (Macridy, Reference Macridy1926b: 60).

Macridy submitted proposals for the restoration of the ruins of the temple of Augustus in the old town of Ankara and gave as an example the arrangement they had made in the garden of the Istanbul archaeological museum. He argued that numerous museums had to be founded in the new capital, with the archaeological museum among the most important. In his words:

No matter how small and poor a museum may be, if its artefacts are exhibited well and there are tags on them informing about what they are, it serves a vast and vital service to the people and particularly the youth. (Macridy, Reference Macridy1926b: 58-60)

Macridy's proposals were fulfilled with the establishment of the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations (Cinoğlu, Reference Cinoğlu2002: 101). A few years later, Macridy, as founding director of the Benaki Museum, took the opportunity to apply his museological vision. When Abdülhak Şinasi visited the Benaki Museum, he wrote the following:

I saw how the Benaki Museum was organized. It reached a point of excellence, which the best museums of Europe could envy and become a paradigm. Now that we give more importance to excavation and museum affairs and we achieve success, we should not only see Macridy Bey, who temporarily accepted and executed this office, when he comes to his homeland as an honourable retired civil servant. We have to continue benefiting from his high expertise either in excavations or in museology. For that reason, considering the significant prospective benefits, we estimate and hope that he could be honoured with a duty such as museum and excavation inspector. We cannot be deprived by a museum expert who took part in so many excavations, when he proved that he could deliver a masterpiece of work such as the Benaki Museum. (Şinasi, Reference Şinasi1934: 292–93)

Despite such lavish praise, Macridy would eventually be side-lined in the Greek and Turkish national histories of archaeology and museology. Nevertheless, he stands as a prominent example of a ‘liminal scientist’ that left a heavy imprint on both countries’ scientific development.

Conclusion

The life and work of Théodore Macridy help shed light on the history of archaeology and museology in the late Ottoman Empire, Turkey, and Greece. While not denying his ethnic background, Macridy avoided drawing attention to his ethnicity in the execution of his duties. He was a secular Ottoman Greek bureaucrat who represented and defended public interest. As Mansel puts it: ‘Macridy distinguished himself with his in-depth knowledge of archaeology, his good manners and technical skills, which he acquired regarding the transportation of large artefacts’ (Mansel, Reference Mansel1948: 13–26).

Although he spent most of his professional life in the Ottoman Empire and republican Turkey and founded one of Greece's leading museums, Macridy is not usually named among the founding fathers of archaeology and museology in the Ottoman Empire, Turkey, and Greece. Because he stood above nationalist narratives and stereotypes, he and scholars like him who straddled national academic communities have remained relatively unrecognized. They did not suit the agenda, which underplayed the importance of minorities in knowledge transfer and overplayed the importance of the founders of national schools. While his liminal identity as Ottoman Greek scientist allowed him to navigate through the Ottoman, Western, and Greek epistemic communities with great dexterity, the domination of nationalist narratives in archaeology and museology condemned him to relative obscurity, despite his outstanding work. This study hopes to draw attention to the life and work of other minority scientists who made a significant contribution to scientific knowledge in the Ottoman Empire but have remained relatively obscure.

Acknowledgements

The work on which this article is based was supported by the Horizon 2020 Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions programme (H2020-MSCA-RISE-2016-734645), gratefully acknowledged here.