No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

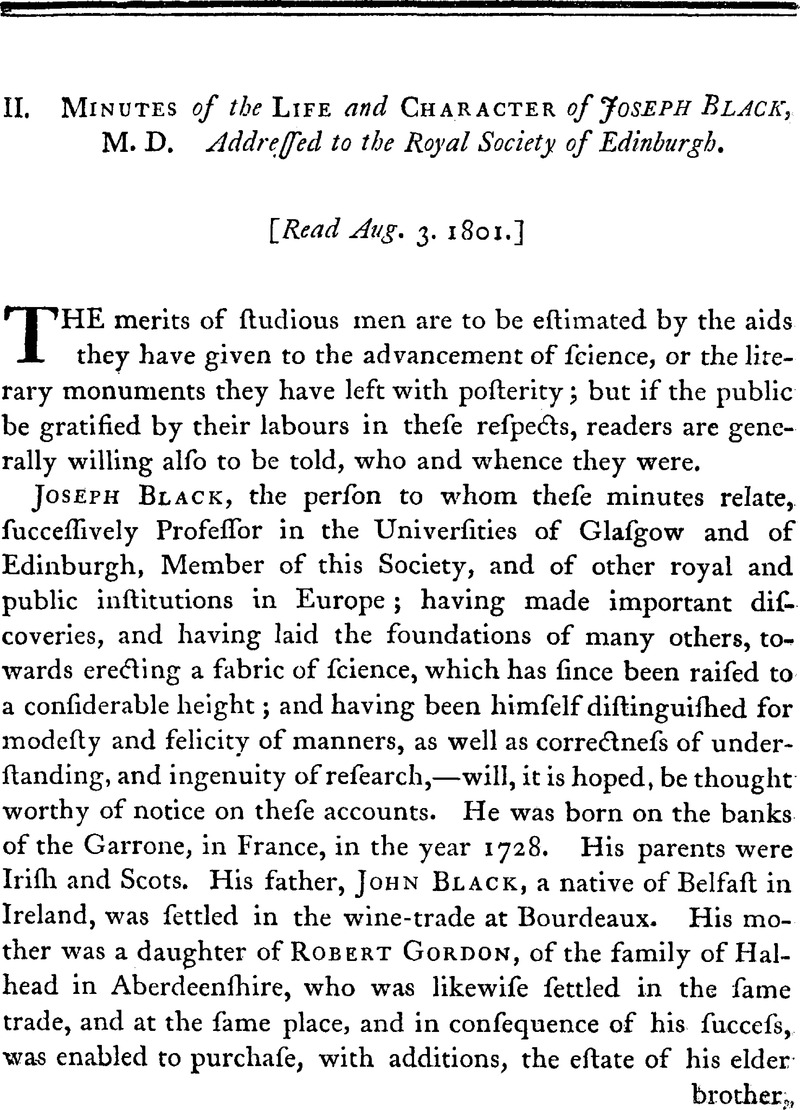

Minutes of the Life and Character of Joseph Black, M. D. Addressed to the Royal Society, of Edinburgh

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 15 March 2016

Abstract

- Type

- Other

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Royal Society of Edinburgh 1997

References

page 103 note * “ Je ne me fais point à l'idée de vous voir quitter Bourdeaux. Je perds le “ plaisir le plus agréable que j'eusse, qui étoit de vous voir souvent, et de m'ou-“blier avec vous.”

page 104 note * Vid. Opuscles Physiques et Chimiques par M. Lavoisier.

page 105 note * To Lavoisier we owe the discovery, that atmospheric air is not homogeneous, but composed of nearly three parts of azot, which is not of any effect in respiration, otherwise than as it dilutes the remaining fourth part, or the vital air, which, without being so diluted, would be too intense either for the purpose of animal respiration or of common fire.

To Priestley we owe the discovery, that the well known corruption or waste of vital air, in the burning of fuel, or the respiration of animals, is repaired in the vegetation of plants.

If in science there might be any choice of truths, I would willingly hope that the decompolkion of water may be found a mistake.

page 106 note * “ Il est bien juste, Monsieur, que vous soyez un des premiers informés des “ progrès qui se font dans une cariere que vous avez ouverte, et dans laquelle nous “ nous regardons tous comme vos disciples.”

page 108 note * It is no doubt a mighty increment in science, to have found such powerful substances operating, as the writer of these minutes apprehends, without gravitation, inertia, or impenetrability, the great bases and columns of the mechanical philosophy.

page 110 note * The writer of this article has little more than heard of chemistry as a branch of general science, and fondly embraced any doctrine as it seemed to connect with the system of nature; but farther, his own studies have been so different, that he would not, if he could, charge his mind with any of his practical details; and he pleads the reader's indulgence, if, under this defect in treating of Black, he hastens to subjoin a description of the man to so imperfect an account of his science.

page 113 note * This society formed itself, about the year 1770, upon a principle of zeal for the Militia, and a conviction that there could be no lafting security for the freedom and independence of these islands, but in the valour and patriotsm of an armed people. It became known, by some whimsical accident, by the name of the Poker Club.

page 114 note * He, too, had carried his studies so far as to obtain a degree in medicine; but an attempt to consult or see him would have been met with a laugh, or some ludicrous fancy, to turn off the subject.

page 115 note * Having said so much of Hutton in this occasional notice, so far short of his merits, it may not be improper to prepare those who may consult him as an author, to meet with a disappointment for which his friends could never rightly account. Though uncommonly luminous and pleasant in conversation, he was obscure, unintelligible, and dry in writing, to an equal degree. His favourite specimens of natural history, he used to say, were God's Books, and he treated the books of men comparatively with neglect. This may, in some measure, account for his want of style or his indifference to language. In company, he spoke to be understood by such as were present, and when obscure, was called upon to explain himself. But alone, he was not aware that others could be at a loss for a meaning so clear to himself. From this circumstance, (notwithstanding many volumes written in the last years of his life, more numerous, perhaps, than all he ever read that were written by others, except the voyages and travels, from which he was perpetually collecting facts to complete his view of the terrestrial system), his very ingenious conceptions, to be received as they ought, must come from some other pen than his own.

page 115 note † On this subject we may consult the following passage of Cicero, Tusc. Quæst. lib. iii. c. 300. “Sed quia, nec qui, propter metum, præsidium reliquit, quod est Ignaviæ; nec qui, propter avaritiam, clam depolitum non reddidit, quod est Injustitiæ; nec qui, propter temeritatem, malè rem gessit, quod est Stultitiæ, Frugi appellari solet. Eas tres virtutes, Fortitudinem, Justitiam, Prudentiam, frugalitas est complexa; etsi hoc quidem commune est virtutum: omnes enim inter se connexæ et jugatæ sunt. Reliqua igitur et quarta virtus, ut sit ipsa Frugalitas. Ejus enim videtur esse proprium, motus animi appetentis regere et fedare; semper adversantem libidini, moderatam in omni re fervare constantiam, cui contrarium vitium Nequitia dicitur.”