African countries have a reputation for having the largest and most unstable cabinets in the world. The size and instability of their cabinets has made some scholars question whether African ministers serve anything more than a ceremonial role, in which ministers capture patronage but do not play a meaningful role as managers of the bureaucracy.Footnote 1 Recent scholarship enhances our understanding of why Africa’s cabinets have grown over time as well as the economic impact of large cabinets.Footnote 2 However, little research systematically analyzes the instability of African cabinets.Footnote 3 This is surprising, given the number of anecdotal accounts of cabinet reshuffles being used to undermine elites, the potential for cabinet reshuffles to spark conflict between elites and leaders, and the detrimental impact of cabinet instability on bureaucratic capacity. Furthermore, variation in cabinet stability, particularly among Africa’s authoritarian regimes, is greater than is often recognized. This variation cannot be explained using the unifying framework of patronage politics that guides most studies of African autocracies.

Building on the literature on authoritarian institutions, I explain how regime type influences leaders’ ability to dismiss ministers without destabilizing their regimes. I argue that leaders of Africa’s dominant party autocracies are more constrained in their ability to dismiss cabinet ministers than are personalist leaders. These constraints reduce the extent of minister dismissals by dominant party leaders as a signal that years of loyal service to the party will not be rewarded with meaningful power sharing. The need to maintain credible power sharing with cabinet ministers also results in more distinct temporal patterns of cabinet reshuffles by dominant party leaders compared to personalist leaders. Dominant party leaders use elections as a mechanism to induce regularity in minister turnover, allowing them to appoint a new group of party elites to cabinet positions while minimizing claims that they are arbitrarily undermining the authority of ministers who have been dismissed. Conversely, personalist leaders are able to engage in more arbitrary patterns of cabinet shuffles in both election and non-election years. Additionally, I argue that the extent of dismissals by military leaders depends upon whether cabinets are composed of officers or civilians, and, if the cabinet is composed of civilians, the extent to which the regime is dependent upon civilians for regime performance and popular support. Military leaders with military cabinets and those who are dependent upon civilian ministers for regime performance and popular support should behave similarly to dominant party leaders.

I test my argument using an original dataset of cabinet ministers from thirty-seven African autocracies between 1976 and 2010. These data include yearly cabinet observations from ninety-four leaders of regimes classified as authoritarian by Geddes, Wright, and Frantz.Footnote 4 I find that cabinet stability varies significantly across authoritarian regime types, with dominant party leaders dismissing fewer cabinet ministers than personalist leaders. Dominant party leaders also tend to engage in large cabinet reshuffles following elections, while personalist leaders engage in more arbitrary patterns of reshuffles in election and non-election years. The results for military leaders are ambiguous for minister dismissals; however, military leaders engage in more post-election horizontal reshuffles than personalist leaders.

This article makes several contributions. First, it qualifies existing accounts of elite politics, patronage, and political stability in Africa. While I agree with Bratton and van de Walle, who argue that elite shuffles are used to ‘regulate and control rent-seeking, to prevent rivals from developing their own bases, and to demonstrate power’,Footnote 5 leaders’ ability to safely engage in reshuffles varies. This has implications for debates over patronage politics and political stability, and helps to explain why, as Arriola notes, patronage politics is frequently cited as a cause of both stability and instability.Footnote 6 Although Africa’s dominant party, personalist, and military leaders rely on patronage politics to build and maintain coalitions, differences in regime type condition the extent of political instability within the cabinet. This shows that formal institutions influence the behavior of leaders and produce meaningful differences in political stability in African autocracies.

Secondly, I provide new empirical support for theories stressing the institutional roots of authoritarian regime and leader stability. It is now well established that autocrats use institutions to co-opt elites and establish credible power-sharing commitments.Footnote 7 However, studies linking the presence of particular authoritarian institutions to increased leader and regime tenure often make untested assumptions about differences in coalition dynamics between regime elites and leaders. This study helps to close the gap between broad support for institutional theories of authoritarian regime and leader stability and the coalition dynamics posited to explain differences in regime and leader tenure. I also add to existing research on authoritarian elections and elite shufflesFootnote 8 by highlighting the heterogeneous effects of elections on cabinet reshuffles across regime types.

Thirdly, this study advances the growing literature on authoritarian cabinets. Although theories of cabinet durability in parliamentary and presidential democracies have been subject to significant cross-national evaluation,Footnote 9 relatively few scholars have studied authoritarian cabinets cross-nationally. Furthermore, existing cross-national studies have not considered cabinet instability in the form of dismissals and horizontal reshuffles,Footnote 10 how cabinet instability varies within autocracies,Footnote 11 or whether authoritarian regime type influences leader decisions to dismiss ministers.Footnote 12 This study provides a general theoretical framework through which studies of authoritarian cabinets can be further specified and subjected to greater empirical scrutiny.

The article proceeds as follows. First, I review explanations of cabinet stability found in the literature on patronage politics and discuss how the broader literature on authoritarian rule applies to cabinet stability in African autocracies. Secondly, I build on the authoritarian institutions literature to develop hypotheses on the extent and timing of minister dismissals and horizontal reshuffles. Thirdly, I introduce the cabinet data, the empirical model, present the results, and discuss several robustness checks. Finally, I explain the implications of the empirical analyses and offer suggestions for future research.

WHAT EXPLAINS CABINET INSTABILITY?

Scholars have identified several factors that influence the stability of cabinets in authoritarian regimes. First, particularly in African autocracies, cabinet instability is often attributed to the practice of patronage politics. Patronage politics, which is often considered the organizing principle of African politics, is characterized by reciprocal, although necessarily unequal, relations between leaders and their coalition of clients.Footnote 13 The inequality within patronage arrangements arises from the leader’s ability to condition continued access to state resources on political support. In resource-poor environments, this allows leaders to form broad coalitions of supporters, often spanning multiple ethnic groups.Footnote 14

As some of the most senior clients of leaders, cabinet ministers often reap substantial benefits from their positions. Cabinet appointments come with many perks including high salaries, cars, homes, policy influence, and opportunities for enrichment through corruption. Access to patronage resources means that ministers can also develop their own patronage networks.Footnote 15 In his study of Houphouët-Boiny’s Democratic Party of Côte d’Ivoire (PDCI), Zolberg argues that ‘regardless of his specific duties as a member of the executive, each minister is also a kind of superrepresentative who keeps in touch with the country through his clientele of deputies’.Footnote 16 Therefore ministers, while accumulating patronage, are important for broadening the base of regime support because of their ties to local and regional constituencies.

Ministerial appointments produce a paradox for leaders in patronage-based polities. Leaders need the support of ministers and the constituencies they mobilize, which provides incentives for cabinet expansion.Footnote 17 At the same time, cabinet appointments provide elites with patronage resources that can be used to challenge the leader.Footnote 18 As Widner argues, ‘only a head of state who is exceptionally clever in his ability to elevate and demote the ‘barons’ with whom he allies himself – or keep them guessing – can long maintain power’.Footnote 19 According to this view, cabinet reshuffles are a strategy of political survival because they prevent ministers from building independent bases of power within particular ministries that could be used to challenge the leader.Footnote 20

Minister reshuffles, while undermining potential challengers, are not without costs. Leaders who dismiss ministers and expel them from the ruling coalition risk elite splits and open conflict. Roessler theorizes that sacking threatening regime elites, particularly those of rival ethnic groups, exchanges coup risk for a future risk of civil war.Footnote 21 For example, South Sudan’s Salva Kiir sacked his entire cabinet in July 2013 following internal power struggles within the South Sudan People’s Liberation Movement, particularly with Prime Minister Riek Machar. Kiir’s decision sparked civil war between his government and those loyal to Machar. Attempts to undermine regime elites and personalize power can also produce coup attempts as remaining regime elites face an increasingly uncertain future.Footnote 22 Recently dismissed ministers, such as former Liberian Minister of Rural Development Samuel Dokie, have co-ordinated with remaining regime elites to oust leaders. In 1983, Dokie organized a coup attempt against President Samuel Doe after reportedly being dismissed for denying a request to transfer $3 million from the Ministry of Rural Development to Doe’s personal account.Footnote 23 Mobutu unraveled a similar plot before it materialized in 1966. In what was known as the ‘Whitsun plot’, recently dismissed Premier Evariste Kimba and three other ministers were accused of plotting against Mobutu and were publicly hanged.Footnote 24 This is not to say that all ministers possess the capability to mobilize civil wars or coups against incumbents. Particularly with coups, mobilization against the incumbent typically requires discontent among members of the military. Nevertheless, the cases from South Sudan, Liberia, and Zaire demonstrate that some ministers are capable of mobilizing such actions. Furthermore, as Francois, Rainer, and Trebbi state, military mobilization against the incumbent rarely takes place ‘without the complicity of important civilian insiders like ministers’.Footnote 25 Thus the decision to dismiss potential rivals from the cabinet is non-trivial.Footnote 26

Secondly, leader tenure provides another explanation for cabinet instability. Leaders who have survived longer in office may be less vulnerable to violent reprisals when undermining regime elites. Scholarship on leader survival shows that authoritarian leaders face high initial risks of being overthrown but become more secure in office as their tenure increases.Footnote 27 Similarly, Svolik argues that established autocrats who have survived the initial high-risk period of their tenure have fundamentally different relationships with regime elites than contested autocrats who have recently entered office.Footnote 28 Contested autocrats must share power with regime elites as they are vulnerable to ‘ally rebellions’. Established autocrats have consolidated their authority and can no longer be threatened by ally rebellions. As a result, ‘key administrators or military commanders are periodically purged, publicly humiliated, rotated across posts, or dismissed and later reappointed’.Footnote 29 Cabinet reshuffles may therefore be a function of leader tenure.

Thirdly, cabinet instability may be explained by the vulnerability of particular authoritarian regime types to elite splits. Leaders of regimes that are more vulnerable to elite splits may limit cabinet change to prevent threatening rifts from emerging within their regimes.Footnote 30 Geddes argues that the propensity of elite splits varies across dominant party, personalist, and military regimes.Footnote 31 Dominant party regimes are defined as those in which the ruling party has ‘some influence over policy, control[s] most access to political power and government jobs, and ha[s] functioning local-level organizations’.Footnote 32 Examples of African regimes coded as dominant party autocracies include the Socialist Party of Senegal regime led by Leopold Senghor and Abdou Diouf and the Zimbabwe African National Union-Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF) regime led by Robert Mugabe. Personalist regimes are those in which an individual leader controls personnel appointments and policy. The regimes of Blaise Compaoré in Burkina Faso and Yahya Jammeh in Gambia are coded as personalist.Footnote 33 In military regimes, a group of military officers influences policy decisions and controls access to political power. For example, Geddes codes Justin Lekhanya’s regime in Lesotho and Ibrahim Babangida’s regime in Nigeria as military.

Geddes expects the risk of elite splits to be low in dominant party and personalist regimes and high in military regimes. Dominant party regimes, despite relying on broad coalitions that often include rival factions, can minimize elite splits through their dominance over the political system. Rival factions are discouraged from challenging the dominant faction because doing so risks regime breakdown and thus the benefits of holding office in a system monopolized by a single party.Footnote 34 Similarly, Brownlee argues that dominant party regimes ‘harness elites together’ by reassuring ‘power holders that their immediate and long-term interests are best served by remaining within the party organization’Footnote 35 Conflict between rival factions is thus prevented by mutual interest in sustaining the regime.

Elites splits are discouraged in personalist regimes by the leader’s control over patronage and the security apparatus, as well as the exclusion of rival factions. As Geddes argues, ‘As long as the dictatorship is able to supply some benefits and has a sufficiently competent repressive apparatus to keep the probability of successful plotting reasonably low, they [regime elites] will remain loyal.’Footnote 36 Similarly, Bueno de Mesquita et al. argue that authoritarian regimes with small winning coalitions, which include many personalist regimes described by Geddes, encourage loyalty between regime elites and the leader.Footnote 37 Although elites in small winning coalition systems have access to substantial private resources, they are discouraged from using those resources to challenge the incumbent because the likelihood of successfully challenging the leader and being included in a subsequent small coalition system is small.

Conversely, Geddes argues that military regimes are vulnerable to elite splits that emerge over personal rivalries or policy differences. When rival factions emerge within military regimes, soft-line factions within the regime will voluntarily exit politics and return to the barracks in an attempt to preserve military unity.Footnote 38 Since returning to the barracks allows the majority of officers to continue their military careers and improve their post-tenure fates,Footnote 39 other factions follow the first move of soft-line factions and return to the barracks as well. The vulnerability to elite splits, interest in maintaining unity within the military, and improved post-tenure fates for voluntarily returning to the barracks thus explains the short tenure of military regimes.Footnote 40

On its own, Geddes’s discussion of elite splits suggests that both personalist and dominant party leaders should face lower risks of elite splits after cabinet reshuffles than military leaders. However, Geddes only mentions that personalist leaders engage in frequent elite shuffles.Footnote 41 Personalist leaders are expected to utilize elite shuffles to undermine challenges from rival factions and capture greater rents for the majority faction. Conversely, elite shuffles in dominant party regimes are mentioned only tangentially. For instance, Geddes’s game theoretic account of politics in dominant party regimes shows that excluding rival factions is risky ‘because exclusion gives the minority an incentive to try to unseat the majority’.Footnote 42 While Geddes’s theoretical logic may be sound, its application to the stability of authoritarian cabinets leaves an additional puzzle. The distinction between personalist and dominant party regimes by Geddes, Wright, and Frantz is mainly based upon whether the leader or the party controls policy and political appointments. However, leaders of Africa’s dominant party and personalist regimes retain formal control over cabinet appointments and dismissals. Even in Botswana, where the Botswana Democratic Party is highly institutionalized, the president has the authority to appoint and dismiss cabinet ministers. In other highly institutionalized dominant party regimes such as Tanzania’s Chama Cha Mapinduzi regime, the president makes cabinet appointments after consultation with the prime minister. Nevertheless, the Tanzanian president can revoke appointments without the approval of party leaders.

The lack of formal control over cabinet appointments and dismissals along with Geddes’s expectation that personalist and dominant party regimes are relatively resistant to elite splits produces ambiguity over the expected patterns of cabinet shuffles in Africa’s dominant party regimes. This contrasts with military regimes, where Geddes’s logic suggests that threatening rivalries should emerge when leaders frequently shuffle officers out of cabinet positions. In the next section, I build on studies of authoritarian institutions to explain the relative constraints faced by dominant party, personalist, and military leaders when shuffling ministers and how these constraints influence patterns of minister dismissals and horizontal reshuffles.

Regime Type, Elections, and Cabinet Instability

My explanation of cabinet stability in African autocracies focuses on the different power-sharing dynamics between leaders and cabinet ministers in dominant party, personalist, and military regimes. Rather than expecting cabinets in African autocracies to be similarly unstable as in the literature on patronage politics, or that the relative resistance to elite splits determines the extent of elite shuffling, I explain why dominant party leaders face greater constraints on their ability to shuffle cabinet ministers than personalist leaders, and provide several countervailing expectations for the constraints faced by Africa’s military leaders. Furthermore, I expect more distinct temporal patterns in cabinet reshuffles in dominant party regimes, with leaders shuffling ministers following elections to establish regular patterns of cabinet turnover that reward new elites and serve as a bulwark against claims of failed power sharing.

Scholars of authoritarian regimes have begun to stress not only the importance of power-sharing institutions, but also the credibility of power-sharing commitments between leaders and elites.Footnote 43 Credible power-sharing commitments are most important for dominant party leaders, as their rule depends on their ability to co-opt broad coalitions of elites. Elites, particularly those from rival factions, have few reasons to acquiesce to co-optation into a regime that does not offer them increased patronage opportunities and policy influence. Magaloni argues that parties solve this commitment problem when they are expected to persist into the future and can ‘(a) control access to power positions, spoils, and privileges; and (b) deliver on the promise to promote those who join the organization’.Footnote 44 Additionally, both Magaloni and Svolik emphasize that credible power sharing requires that elites can credibly threaten rebellion against leaders who renege on power-sharing commitments.

Rather than focusing on power sharing between leaders and elites broadly as do Magaloni and Svolik, I focus specifically on the relationships between leaders and cabinet ministers. As with Geddes’s definition of dominant party regimes, Magaloni suggests that the party must control ministerial appointments and dismissals for power sharing to be credible within the cabinet.Footnote 45 While this is not the case in the African regimes studied here, I argue that dominant parties still constrain the leader’s ability to arbitrarily dismiss ministers. To make power sharing credible, dominant party regimes must establish a system of regular promotion in exchange for party service. Party members must also be rewarded with meaningful increases in patronage and policy influence as they rise through the ranks. Without a regular system of promotion and increasing benefits, current and prospective members of the party have few incentives to incur the ‘sunk political costs’ at the lower levels of the party.Footnote 46 The promise of promotion, policy influence and patronage is particularly important at the higher levels of the party as these individuals have invested the most time and effort in party service. Few party elites can expect to be selected as the next leader, but those who have risen through the party ranks are likely to expect cabinet appointments, or other prestigious positions in parastatals or party committees, for their years of loyal service. Because of the importance and prestige associated with cabinet appointments, leaders who rapidly dismiss ministers send a public signal that political promotions at the highest level do not provide meaningful power sharing. This undermines the party at the upper and lower levels. High-ranking members realize that they can no longer expect meaningful political promotion, while lower-ranking members, who often engage in the most costly party service, begin to question whether their investment in the party will be rewarded. Thus party membership begins to lose its appeal, creating splits among party factions and leading some to challenge the incumbent by supporting rebellion or forming their own political parties.

Conversely, personalist leaders face lower risks of compromising their regimes by rapidly shuffling ministers. Unlike dominant party regimes, personalist regimes do not depend upon broad coalitions and are less reliant on the service of lower-ranking regime members. Personalist leaders, having often gained their positions through intense struggles,Footnote 47 implement a variety of coup-proofing measures to prevent successful rebellion against their rule, including the recruitment and promotion of soldiers based on family, ethnic, or religious ties.Footnote 48 For example, most Togolese officers serving under Gnassingbe Eyadema were coethnics of the Kabye ethnic group, and many senior commanders were from Eyadema’s home village.Footnote 49 Coup proofing can also involve counterbalancing military forces by creating rival factions or paramilitary units.Footnote 50 Mobutu engaged in counterbalancing in 1974 when he replaced the unified General Staff with four separate departments under different leadership.Footnote 51 Similarly, Blaise Compaoré established a separate Regiment of Presidential Security, which served as an ‘army within an army’ that was better equipped than the regular armed forces.Footnote 52 Furthermore, most elites will refrain from challenging personalist leaders so long as the leader maintains control over patronage distribution.Footnote 53 This allows personalist leaders to rapidly dismiss ministers without facing an organized response.

The constraints on Africa’s military leaders are less clear. As Geddes describes, military regimes rely on power sharing between the leader and a group of officers. While this suggests that military regime cabinets should be relatively stable compared to those in personalist regimes, it is not clear that this logic holds among Africa’s military regimes. This is because the cabinets of Africa’s military regimes are often quickly ‘civilianized’Footnote 54 by replacing military officers serving in the cabinet with civilian ministers. Anene argues that civilian cabinet appointments serve to improve government effectiveness, address demands for civilian rule, and build bases of support separate from the military.Footnote 55 This ‘civilianization’ process produces cabinet instability in the early years of military regimes as civilians replace military officers. However, it is unclear whether military leaders face the same power-sharing constraints with civilian ministers as they do with high-ranking officers. For instance, civilian ministers are less able to punish military leaders who engage in frequent cabinet reshuffles than are military ministers, which could result in more extensive and frequent cabinet reshuffles. At the same time, Anene’s argument that civilian ministers improve government effectiveness, accommodate demands for civilian rule and build support outside the military suggests that military leaders may depend on power sharing with civilian ministers as well, resulting in fewer cabinet reshuffles than in personalist regimes. Although existing theory is ambiguous about the stability of cabinets in Africa’s military regimes, empirical analyses can help explain the extent to which Africa’s military leaders are constrained by power-sharing commitments with ministers. If the lesser ability of civilian ministers to punish military leaders is most important, patterns of cabinet reshuffles by Africa’s military leaders should be similar to those of personalist leaders. Alternatively, if Africa’s military leaders depend on civilian ministers for regime performance and popular support, they should engage in patterns of cabinet reshuffles that are more consistent with dominant party leaders.

The discussion above produces several testable hypotheses. First, despite arguments that dominant party regimes face a low risk of elite splits, I argue that dominant party leaders dismiss fewer ministers than personalist leaders. Given the theoretical ambiguity over the reshuffling behavior of Africa’s military leaders, I seek only to test whether they behave similarly to either dominant party and personalist leaders, following the countervailing logics described above. These arguments produce Hypothesis 1.

Hypothesis 1: Dominant party leaders dismiss fewer ministers than personalist and military leaders.

While Hypothesis 1 examines differences in rates of minister dismissals across authoritarian regime types,Footnote 56 it does not predict the extent to which leaders horizontally shuffle ministers between ministerial portfolios. This distinction is important as dismissing ministers often provides a different signal to regime elites than horizontally reshuffling ministers. Horizontal reshuffles provide a middle ground between dismissing problematic ministers and allowing them to continue developing power and autonomy within a particular portfolio, and provide a mechanism to reduce ministerial moral hazard.Footnote 57 I expect all authoritarian leaders to use horizontal reshuffles to reduce ministerial moral hazard, and that overall rates of horizontal reshuffles are similar across regime types. While the relative lack of power-sharing constraints faced by personalist leaders may be expected to result in more horizontal reshuffles, I argue that this simply allows personalist leaders to engage in more dismissals instead, with horizontal reshuffles reserved to check the power and autonomy of close allies who remain in the cabinet for longer periods of time. This leads to Hypothesis 2.

Hypothesis 2: Dominant party, military, and personalist leaders engage in horizontal reshuffles at similar overall rates.

Finally, maintaining credible power sharing with ministers in dominant party regimes should produce more distinct temporal patterns of dismissals and horizontal reshuffles. I expect dominant party leaders to engage in major cabinet reshuffles predominantly following elections. Magaloni argues that elections in dominant party autocracies establish regular power-sharing mechanisms among party elites.Footnote 58 They also encourage party unity by providing public signals of regime strength, provide the leader with information on regime supporters and opponents, and encourage the opposition to operate within the existing set of institutions rather than seeking change through violent means.Footnote 59 Regularity in cabinet turnover is important for the credibility of power sharing as it mitigates claims that the leader is arbitrarily dismissing ministers to undermine their authority. By dismissing and horizontally reshuffling ministers at regular intervals, dominant party leaders establish norms of turnover that allow them to reward a new group of party elites with cabinet appointments while minimizing impressions that power-sharing commitments have been breached. Furthermore, in party regimes where ministers must be selected from members of the legislature, seats can be lost in free or manipulated elections, partially reducing the need for overt dismissals.

Many of Africa’s personalist regimes also hold elections, but the lesser importance of credible power sharing results in more arbitrary patterns of minister reshuffles in both election and non-election years. As in Hypothesis 1, the extent to which military leaders increase dismissals and horizontal reshuffles following elections depends on the power-sharing constraints they face vis-à-vis civilian ministers. If military leaders depend on power sharing with civilian ministers for the performance of (and support for) the regime, they will engage in more dismissals and horizontal reshuffles following elections. However, if military leaders are less dependent upon civilian ministers, we will see relatively smaller increases in dismissals and horizontal reshuffles following elections. This leads to Hypothesis 3.

Hypothesis 3: Dominant party leaders increase dismissals and horizontal reshuffles to a greater extent following elections than personalist or military leaders.

DATA AND METHODS

To test these hypotheses, I collected data on the composition of cabinets for ninety-four leaders in thirty-seven African countries from 1976 to 2010 using volumes of Africa South of the Sahara.Footnote 60 The unit of analysis is the leader-year, with leaders identified using the Archigos data.Footnote 61 For each leader-year in the sample, I code the names of cabinet ministers and the portfolios they held. This includes all individuals listed as cabinet members by Africa South of the Sahara, with the exception of the leader.Footnote 62 Taking the leader-year as the unit of analysis means that cabinet changes occurring because of leadership changes are excluded from the analyses. Cabinet instability caused by leader turnover affects governance, particularly given the prevalence of coups in Africa, but it does not speak to the constraining role of dominant party institutions. Therefore, the hypotheses are directed only at dismissals and horizontal reshuffles that occur during a given leader’s tenure. A complete list of leaders, leader-years, and regime type codings is included in the Appendix.

Dependent Variables

The first dependent variable measures the number of ministers that leave the cabinet in each leader-year. The coding of this variable does not distinguish between minister dismissals, deaths in office and voluntary resignations because of limited data on the specific conditions surrounding minister exits. While this only provides a proxy of minister dismissals, there are four primary reasons to believe that this coding does not unduly bias the results in favor of the hypotheses outlined above. First, minister deaths are likely to be randomly distributed across dominant party, personalist, and military regimes. Secondly, there are few reasons to expect more voluntary resignations in either dominant party, military or personalist regimes. Personalist regimes with small winning coalitions provide ministers with strong incentives to remain loyal to the leader,Footnote 63 even though personalist leaders need not remain loyal to their ministers. In dominant party regimes, the dominant strategy of ministers, including those from rival factions, is to remain in office.Footnote 64 While the theoretical logic is more ambiguous for ministers in military regimes, there are few reasons to expect higher rates of voluntary resignations compared with dominant party or personalist regimes. Thirdly, voluntary resignations often occur when ministers defect to the opposition and seek to challenge candidates from the incumbent regime in legislative or executive elections. This requires multiparty competition that is not limited to a single authoritarian regime type. Fourthly, voluntary resignations often occur because ministers are unsatisfied with the level of power sharing or to pre-empt dismissals or worse from the leader. Dickie and Rake describe such a situation near the beginning of Hastings Banda’s tenure in Malawi: ‘His determination to go his own way cost him dearly. He lost much needed talent when seven ministers went into exile after charges of plotting.’Footnote 65 This suggests that many voluntary resignations are the outcome of failed power sharing that my theory seeks to highlight. Therefore, the number of ministers exiting the cabinet each year represents a reasonable proxy of minister dismissals.

The second dependent variable measures the number of ministers shuffled horizontally to new ministerial portfolios each year. For example, I code Zimbabwe’s Emmerson Mnangagwa as being horizontally reshuffled in 2009 when he left his previous post as Minister of Rural Housing and Amenities to be reappointed as Minister of Defense. Horizontal reshuffles are expected to reduce ministerial moral hazard without severely breaching power-sharing commitments. Additional information on the coding of both minister dismissals and horizontal reshuffles is provided in the Appendix.

Independent Variables

The main model specifications contain two variables of interest. The first is authoritarian regime type. Following the coding of Geddes, Wright, and Frantz,Footnote 66 I include dummy variables for dominant party regimes and military regimes, leaving personalist regimes as the reference category. In addition to dominant party, military, and personalist regimes, Geddes, Wright, and Frantz also code hybrids of these pure types. I follow their convention of coding hybrid regimes as the first regime type listed in the main analyses. Thus party–personalist or party–military hybrids are coded as dominant party regimes. I also estimate additional models disaggregating hybrid regimes, which are discussed below.

The second independent variable of interest is an indicator of whether or not an executive or legislative election was held before the cabinet measurement in year t. This requires special attention as the month in which cabinet composition is recorded in Africa South of the Sahara varies by country, leader, and year. The variable Election takes a value of 1 if there was an executive election, legislative election or both after the cabinet measurement at time t–1 but before the cabinet measurement at time t. Data on elections come from the NELDA dataset.Footnote 67 Elections are expected to induce cabinet changes in authoritarian regimes just as they do in democracies, even if they are driven by different motivations. However, increases in dismissals and horizontal reshuffles following elections are expected to be greater in dominant party regimes where power-sharing commitments discourage arbitrary reshuffles in non-election years. Elections occur in 20 per cent of dominant party leader-years, 20 per cent of personalist leader-years, and 11 per cent of military leader-years in the sample.

Controls

I control for a variety of factors that may also influence cabinet instability. First, a leader’s ability to co-opt clients is influenced by access to resource rents.Footnote 68 Leaders with access to resource rents can more easily buy the support of political opponents, perhaps reducing the need for credible power-sharing commitments and producing greater cabinet instability. I control for access to resource rents using data on total resource rents as a percentage of GDP from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators.Footnote 69 Because of missing data, the variable Resource Rents is coded 1 if the median of available data on total resource rents for a particular country is greater than the median total resource rents for available observations across all countries, and 0 for all other leader-years. Similarly, I also control for Ln(GDP per Capita) and GDP Growth as additional measures of the resource constraints faced by leaders.

Secondly, cabinet instability is common following failed coup attempts as leaders seek to purge coup supporters and critics from the regime. Cameroon’s Paul Biya, while initially retaining most of former President Ahmadou Ahidjo’s cabinet, shuffled ministers extensively after uncovering a coup plot in 1983 hatched by Ahidjo, Maj. Ibrahim Oumharou, and Capt. Ahmadou Saleh and again after an actual coup attempt by Ahidjo and Saleh materialized in 1984. The dismissals targeted Ahidjo allies, particularly ministers from Ahidjo’s base in Cameroon’s North and Extreme North provinces. In total, Biya dismissed ten ministers from the North and Extreme North provinces following the failed coup attempt. The variable Coup Attempt indicates whether a failed coup attempt took place after the cabinet measurement at time t – 1 but before the cabinet measurement at time t, and is coded using data from Powell and Thyne.Footnote 70

Thirdly, scholars have stressed the importance of ethnic balancing within African cabinets. As Francois, Rainer, and Trebbi show,Footnote 71 cabinet appointments are allocated proportionately to ethnic group size in African states. For example, Kenneth Kaunda carefully balanced his cabinet by appointing individuals roughly in proportion to their group’s share of the Zambian population.Footnote 72 However, this ethnic balancing is argued to be a source of instability. Ethnically diverse cabinets may increase cabinet instability by producing distrust between leaders and ministers from rival ethnic groups. Roessler argues that reciprocal maneuvering of leaders and ethnic elites, both trying to consolidate their positions within the regime, undermines power-sharing commitments and results in rival ethnic elites being excluded from the regime.Footnote 73 Additionally, ethnic diversity increases the number of possible minimal winning coalitions, giving leaders the ability to marginalize certain groups and form an alternative coalition.Footnote 74 I include the variable Senior Partners from Version 3 of the Ethnic Power Relations dataset to measure the extent of ethnic power sharing at high levels within the regime.Footnote 75 This variable captures the extent of formal or informal power sharing in senior positions within the executive and is measured as the percentage of the population represented by coethnics in senior positions.

Fourthly, I account for the effect of leader tenure on cabinet instability. Scholars of parliamentary democracies theorize that leaders face adverse selection problems when making cabinet appointments.Footnote 76 After imperfect appointments are made, leaders observe the true abilities of their appointees and shuffle them to portfolios that better suit their skill set or remove them from the cabinet entirely. Although authoritarian leaders are likely to have different minister selection criteria,Footnote 77 selection problems may still produce instability early in the tenure of leaders. Also, the hazard of losing office declines over time for authoritarian leaders,Footnote 78 which can produce more frequent reshuffles early in the tenure of leaders as they seek to prevent ministers from capitalizing on the initial weakness of their grasp on power. I control for duration dependence in a flexible way by including a cubic polynomial of leader tenure in all models.Footnote 79

Finally, because the dependent variable does not distinguish between dismissals and voluntary resignations, I control for the presence of multiparty elections in the legislature using the Lexical Index of Electoral Democracy dataset.Footnote 80 This variable addresses the possibility that ministers are more willing to voluntarily exit the cabinet when they can legally challenge the incumbent through an opposition party.

Estimation Method

Since both dependent variables represent discrete numbers of ministers dismissed or horizontally reshuffled each year, count models provide an appropriate estimation framework. I choose the more flexible negative binomial distribution over the Poisson as both dependent variables show signs of overdispersion. The natural logarithm of cabinet size is included as an offset variable in all models to account for differing levels of exposure to dismissals and horizontal reshuffles across leader-years.Footnote 81 For instance, forty-one ministers faced the possibility of dismissal or horizontal reshuffle in Laurent Gbagbo’s 2006 cabinet in Côte d’Ivoire, but only fourteen ministers faced these actions in Moussa Traore’s 1980 cabinet in Mali.

Additionally, the panel structure of the data presents the potential for leader-specific effects, non-constant variance across leaders, and autocorrelation within the tenure of leaders. Fixed effects are commonly used to control for unit-specific effects in panel data settings; however, the lack of variation in the regime type variables within individual leaders’ tenures prevents their use. Non-constant error variance and autocorrelation are addressed using standard errors clustered by leader. Further robustness checks allowing for leader-specific random effects and modeling first-order autocorrelation directly through the generalized estimating equations (GEE) framework are discussed below and presented in Appendix Tables A3 and A4. These alternative modeling choices do not alter the main findings.

RESULTS

Table 1 reports the results of the negative binomial regressions. Models 1 and 2 estimate the effects of regime type and elections on minister dismissals. In Model 1, the effects of the regime type and election variables are modeled independently. As expected, the Party Regime coefficient is negative and significant, indicating that dominant party leaders dismiss fewer ministers than personalist leaders. The Military Regime coefficient is negative but only significant at the 10 per cent level. Additionally, an F-test of the equality of the Party Regime and Military Regime coefficients reveals no significant difference (F=1.09, p=0.30). Therefore, dominant party leaders dismiss fewer ministers than personalist leaders, but the results for military leaders are ambiguous. Finally, the Election coefficient is positive and significant, indicating that minister dismissals increase following elections.

Table 1 Minister Dismissals and Horizontal Reshuffles

Note: pooled negative binomial regressions with standard errors clustered by leader. *p<0.1; **p<0.05; ***p<0.01

Model 2 tests Hypothesis 3 by interacting the Party Regime and Military Regime variables with Election to determine whether post-election increases in dismissals differ across regime types. The Party Regime coefficient remains negative and significant, showing that dominant party leaders dismiss fewer ministers in non-election years than personalist leaders. The Military Regime coefficient is negative but not significant at any conventional level, suggesting no differences in non-election year shuffles by military and personalist regime leaders. The positive and significant coefficient for Election shows that personalist leaders increase dismissals following elections. Consistent with Hypothesis 3, however, the Party x Election coefficient is positive and significant, which demonstrates that dominant party leaders increase dismissals following elections to a greater extent than personalist leaders. The Military x Election coefficient is negative but not significant at any conventional level, indicating that post-election dismissal increases by military and personalist leaders are similar. As in Model 1, F-tests fail to reject the hypothesis that dominant party and military regimes have the same effect in non-election years (F=2.35, p = 0.13) or that elections have the same effect in dominant party and military regimes (F=2.39, p = 0.12). Taken together, these results show that the hypothesized differences between dominant party and personalist leaders are supported, but the differences between military leaders and either dominant party or personalist leaders are ambiguous.

Models 3 and 4 in Table 1 estimate the effects of regime type and elections on horizontal reshuffles. The coefficients for Party Regime and Military Regime are not significant in Model 3. This provides support for Hypothesis 2, which predicts similar overall rates of horizontal reshuffles by dominant party, personalist, and military leaders. As expected, the Election coefficient is positive and significant for horizontal shuffles. Model 4 interacts Party Regime and Military Regime with Election to test whether horizontal reshuffles differ across regime types in election and non-election years. The Election coefficient, now representing the effect of elections in personalist regimes, is reduced in magnitude, but remains positive and significant. The coefficients for the Party x Election and Military x Election terms are positive and significant, showing that the post-election increases in horizontal reshuffles of dominant party and military leaders are greater than those of personalist leaders. However, an F-test shows that the effects of elections in dominant party regimes and military regimes do not differ from each other (F=0.16, p = 0.69). Thus while the dismissal behavior of military leaders is ambiguous, the horizontal reshuffles of military leaders resemble those of dominant party leaders.

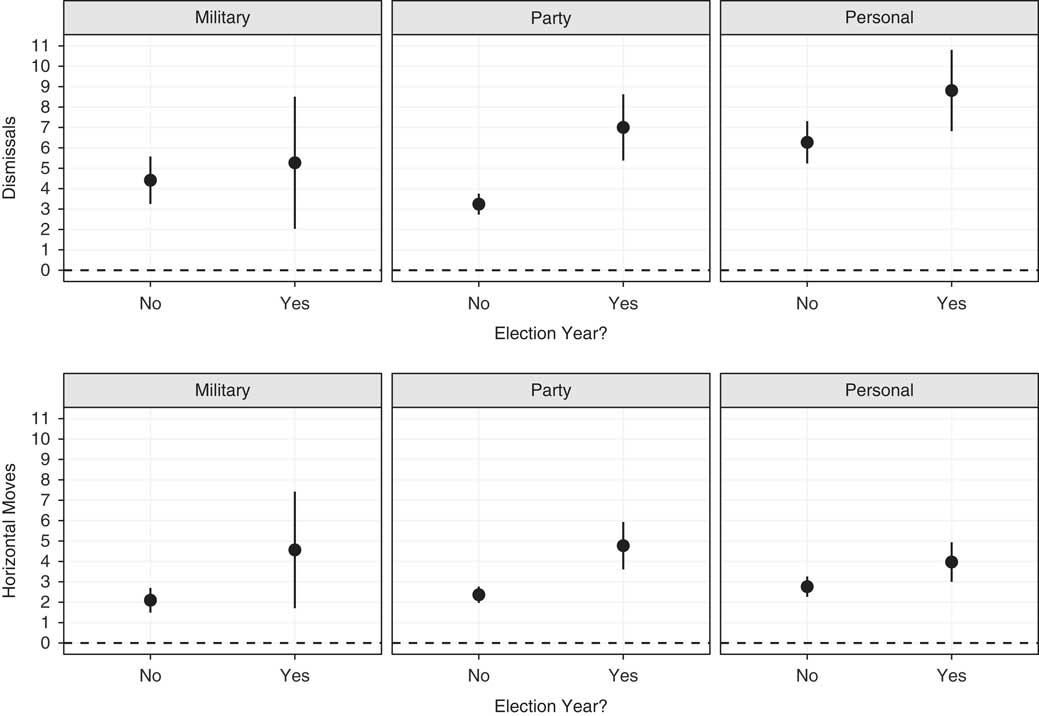

Since the substantive effects of the negative binomial coefficients are difficult to interpret, I present the results graphically in two ways. First, Figure 1 plots the predicted number of minister dismissals and horizontal reshuffles for military, party, and personalist leaders during election and non-election years. The predictions are calculated holding the control variables at their sample means for the particular regime type, with the exception of Multiparty, which takes a value of 1 for all regime categories and Coup Attempt and Resource Rents, which take a value of 0 for all regime categories. The plot of predicted dismissals in the top panel of Figure 1 follows the same general patterns shown in Table 1. Dominant party leaders are predicted to dismiss 3.2 ministers in non-election years compared to 6.3 ministers for personalist leaders. In election years, dominant party leaders are predicted to dismiss seven ministers compared to 8.8 ministers for personalist leaders. Therefore, dominant party leaders clearly have more stable cabinets in non-election years and tend to refrain from larger numbers of dismissals until after elections. Moreover, as Table 1 demonstrates, the differences between military regimes and either party or personalist regimes are less clear in Figure 1. Military leaders are predicted to dismiss 4.4 ministers in non-election years and 5.3 ministers in election years, but the wide confidence intervals for the predictions make them statistically indistinguishable from the predictions for either party or personalist leaders.Footnote 82

Fig. 1 Predicted dismissals and horizontal reshuffles with 95 per cent confidence intervals Note: predictions calculated using Models 2 and 4 in Table 1 with all variables set to their respective regime type means with the exception of Multiparty and Resource Rents, which are set to 1, and Coup Attempt, which is set to 0 for all regime type categories.

Secondly, I also present the average marginal effects (AMEs) of each variable in Figure 2 following the recommendation of Hanmer and Kalkan.Footnote 83 AMEs are calculated by holding each additional covariate at its observed value rather than the values chosen to calculate the predicted counts in Figure 1. This means that no AMEs are calculated for the Party x Election or Military x Election interactions. Figure 2 shows that the AME of Party Regime is negative and significant for dismissals. This provides additional support for Hypothesis 1. The AME of Military Regime is also negative and significant for dismissals, providing some support for the hypothesis that military leaders’ dependence on civilian ministers for regime performance and popular support produces greater power-sharing constraints than are found in personalist regimes.Footnote 84 As the right panel of Figure 2 shows, the AMEs for Party Regime and Military Regime are both indistinguishable from zero for horizontal reshuffles, which is consistent with Hypothesis 2.

Fig. 2 Average marginal effects on dismissals (a) and horizontal reshuffles (b) with 95 per cent confidence intervals calculated using Models 2 and 4 from Table 1

Estimates for the control variables also demonstrate interesting dynamics, particularly for the Multiparty and Senior Partners variables. The Multiparty coefficient is negative and significant in all model specifications for dismissals and horizontal reshuffles, as are the AMEs displayed in Figure 2. Multiparty competition, even in Africa’s authoritarian regimes, has thus brought greater cabinet stability. The coefficient for Senior Partners is negative and significant for dismissals and positive and significant for horizontal reshuffles, as are the AMEs displayed in Figure 2. This shows that greater ethnic diversity in the executive branch reduces the number of minister dismissals, but increases the rate at which leaders horizontally reshuffle ministers. These results provide an interesting extension of research by Roessler, who finds that commitment problems between African leaders and rival ethnic groups result in exclusion from the regime.Footnote 85 While this may be the case broadly, diversity among senior regime elites appears to restrict the leader’s ability to dismiss ministers. However, following Roessler’s argument, mutual distrust between the leader and rival ethnic elites within the cabinet may result in more horizontal reshuffles as the leader attempts to maintain a diverse coalition while still attempting to undermine the authority of non-coethnic elites.

Robustness Checks

I estimate several additional models to examine the robustness of the results to a number of different modeling and specification choices. One concern is that the estimates in Table 1 are being driven by unobserved leader-specific effects rather than by differences in constraints across regime types. Although leader fixed effects cannot be estimated because regime type does not vary across the tenure of leaders, I adopt three alternative approaches to assess the impact of individual leaders on the main findings.

First, I split the data into dominant party, personalist, and military samples and estimate the effect of elections in each sample while including leader fixed effects. If the estimates in Table 1 are not biased by leader-specific effects, the Election coefficient in models of dismissals should be largest in the dominant party sample. As Table 2 shows, the Election coefficient is approximately three times larger in the dominant party sample than in the personalist sample. Similar to the results in Table 1, the Election coefficient for the military regime sample in Model 3 is positive but is only significant at the 10 per cent level. These findings suggest that leader-specific effects do not bias the estimates of post-election dismissals for dominant party, personalist and military leaders. The split-sample estimate for horizontal reshuffles in Table 2 is also consistent with the findings in Table 1. The Election coefficient is larger in the dominant party sample than the personalist sample, and is largest in the military regime sample. Additionally, the split-sample estimates reveal differences in the effects of control variables not modeled in Table 1. This is particularly the case with the Coup Attempt variable, which is positive and significant only for the personalist leaders. This finding provides indirect evidence of the power-sharing constraints faced by dominant party and military leaders.

Table 2 Split-Sample Fixed Effects Regressions

Note: unconditional fixed effects negative binomial regressions with standard errors clustered by leader. *p<0.1; **p<0.05; ***p<0.01

Secondly, I estimate negative binomial models with leader random effects. The estimates, presented in Appendix Table A3, remain very similar to those in Table 1. Thirdly, I examine the sensitivity of the findings of Models 2 and 4 in Table 1 to the exclusion of single leaders and countries from the dataset. Figures A2 and A3 plot the density of coefficient estimates and p-values obtained for the Party Regime and Party x Election coefficients in Table 1 Model 2 when dropping each individual leader and country from the dataset and re-estimating the model. The results remain consistent across the different subsets of leaders and countries.

Another concern, given the panel structure of the data, is autocorrelation. I address this through the GEE framework.Footnote 86 The estimates from GEE models with an AR(1) working correlation structure are presented in Appendix Table A4. Coefficients for the regime type variables and their interactions with elections remain very similar to those in Table 1.

I also examine the robustness of the regime type coding in two ways. First, the analyses in Table 1 follow the approach of Geddes, Wright, and Frantz by coding party–personalist or party–military hybrids as dominant party regimes.Footnote 87 Importantly, this decision should bias the results against the hypotheses above since Geddes’s coding gives less weight to the party coding where: (1) party membership is highly urban with little grassroots organization; (2) the politburo serves as a rubber stamp for the leader and the leader plays a large role in selecting its members; (3) the government is dominated by one particular group in heterogeneous societies; and (4) nepotism is common in high offices.Footnote 88 As expected, the estimates in Appendix Table A5 show that the Pure Party and Pure Party x Election coefficients increase in magnitude in the dismissal models after including an additional hybrid party variable. However, the coefficients for Hybrid Party and Hybrid Party x Election are not significant. This suggests that the organization, authority, and make-up of dominant party regimes are critical for a party’s ability to constrain the leader.Footnote 89 Secondly, I recode the Party Regime variable to distinguish between leaders who founded the party regime and those who became the leader of a pre-existing party regime. If the non-founding leaders of party regimes are similarly or more constrained than founding party leaders, the theoretical argument above gains additional support. The estimates in Table A10 show that both founding and non-founding party regime leaders follow the pattern of Party Regime in Table 1; however, the coefficients for the non-founding party leader and its interaction with elections are larger than those for founding party leaders. This also eases concerns that the regime type coding is endogenous to cabinet reshuffles.

Next, the main findings may be driven by dominant party regimes being more democratic than military or personalist regimes. For example, Botswana is coded as a dominant party dictatorship, has relatively little cabinet instability and is considered democratic by most African politics scholars. While the estimates in Table 1 control for multiparty regimes, I also control for Polity 2 scores in Table A6.Footnote 90 Controlling for the level of democracy produces coefficients that are nearly identical to those in Table 1. This increases confidence that the results are not merely due to the presence of countries like Botswana or Tanzania that score high on the Polity index, have relatively stable cabinets, but are labeled as dominant party dictatorships by Geddes, Wright, and Frantz.Footnote 91 Similarly, as Roberts shows, the presidential or parliamentary structure of authoritarian regimes affects their overall durability and cabinet stability.Footnote 92 While most African autocracies in the sample are presidential systems, countries such as Botswana and Ethiopia under Meles Zenawi have parliamentary systems. Table A7 shows that parliamentary systems do reduce both dismissals and horizontal reshuffles of cabinet ministers. However, estimates for the variables of interest remain very similar.

Finally, I estimate models using a restricted sample of cabinet ministers that excludes junior, assistant and deputy ministers following the coding of Arriola, and conduct an extreme bounds analysis on the coefficients of Models 2 and 4 of Table 1.Footnote 93 The estimates presented in Table A8 show that the main findings are not driven by my more inclusive definition of the cabinet. The extreme bounds analysis (Table A12 and Figure A4) shows that the findings for the variables of interest are robust to alternative model specifications.

CONCLUSION

This article addresses gaps in the research on patronage politics and authoritarian institutions to explain variation in cabinet instability between dominant party, personalist, and military dictatorships in Africa. Although the literature on patronage politics thoroughly discusses the motivations driving African autocrats to frequently reshuffle their cabinets, it fails to explain the constraining role of dominant party regimes. The literature on authoritarian institutions, while describing the ability of dominant party regimes to establish credible power sharing between the leader and party elites, relies on studies of leader and regime tenure for empirical support. This study breaks new ground by examining how dominant party regimes constrain leaders’ ability to reshuffle cabinets, thus providing a more direct look at elite power sharing at the highest level.

I show that dominant party regimes influence the extent and timing of minister dismissals in African dictatorships. Dominant party leaders dismiss far fewer ministers than do personalist leaders. Also, dominant party leaders tend to engage in large numbers of dismissals and horizontal reshuffles only after elections to establish regular patterns of cabinet change and increase the credibility of power sharing. Conversely, personalist leaders face fewer constraints and engage in more arbitrary patterns of dismissals and horizontal reshuffles that vary less between election and non-election years. Patterns of dismissals in Africa’s military regimes exhibit greater variation and are indistinguishable from either personalist or dominant party regimes. Military leaders appear to engage in more horizontal reshuffles following elections, but this should be interpreted with caution, as there are few elections in military regimes.

These findings broadly support the literature on authoritarian power sharing, but also add important nuance. I demonstrate that dominant party leaders need not relinquish control over cabinet appointments and dismissals to the party for credible power sharing to take place. Instead, the structure of dominant party regimes constrains leaders’ ability to shuffle ministers arbitrarily. I also explain that power-sharing dynamics in military regimes become more complex as civilians are appointed to senior positions within the regime. Additionally, I show that explanations of elite shuffles rooted in the patronage politics literature are primarily applicable to personalist regimes. While future work is needed to assess the generalizability of these findings beyond sub-Saharan Africa, the theory is sufficiently general to be applied to other regions.

Finally, this research highlights two particularly important areas of future research. First, more research is necessary to understand how regime type influences the risk of dismissal or reappointment for individual ministers and how individual minister characteristics influence such risks. Recent work has begun to examine the influence of gender on the tenure of individual ministers,Footnote 94 but more work is needed on the effects of ethnic identity and portfolio prestige on minister tenure. For instance, further investigation of the divergent effects of ethnic diversity in the executive on dismissals and horizontal reshuffles can provide an important addition to Roessler’s work on ethnic exclusion in African states.Footnote 95 Secondly, future work can build on recent studies of party system development in Africa to better understand the conditions under which ministers and other elites defect to build opposition parties or join existing opposition parties.Footnote 96