In July 2016, Timmonsville, South Carolina––a majority-Black town with a majority-Black town council and a Black mayor––became the latest among several local municipalities to pass an ordinance regulating the public presentation and dress of its residents. In particular, Provision D of Ordinance No. 543 made it illegal to “wear pants, trousers, or shorts such that the known undergarments are intentionally displayed [or] exposed to the public.” First-time offenders receive an official warning; repeat offenders face a fine between $100 and $600, depending on the frequency and severity of the infraction (Hider Reference Hider2016). Supporters claim that so-called sagging pants bans “instill a sense of integrity in young people” and “help to better the next generation” (McCray Reference McCray2016). Opponents argue that the bans are discriminatory and target “a clothing style typically associated with young African-American males” (WDSU 2013). Despite these objections, sagging pants bans remain in municipal codes across the United States and garner the support of diverse constituencies, including support from many Black Americans who identify with the targeted group.Footnote 1

In this way, sagging pants ordinances—as odd as they may seem—are not unique. Instead, they represent a broad class of punitive social policies that garner significant support from Black Americans despite their negative consequences for group members.Footnote 2 To be sure, diversity in Black Americans’ views on these and other issues should not surprise us. We should expect individuals who belong to large and diverse social groups to disagree on matters of public policy. Still, Black support for punitive policies that target group members is noteworthy for at least two reasons. First, this support challenges expectations of in-group favoritism (Tajfel and Turner Reference Tajfel, Turner, Austin and Worchel1979) and highlights the limits of group-based solidarity (cf. Dawson Reference Dawson1994; Miller et al. Reference Miller, Gurin, Gurin and Malanchuk1981), especially as it is marshaled on behalf of more stigmatized group members. In fact, by attending to this site of disagreement among Black Americans, the current project builds on and extends scholarship that has long complicated overly general claims of solidarity and group cohesion present in the Black politics canon (e.g., Alexander-Floyd Reference Alexander-Floyd2007; Bunyasi and Smith Reference Bunyasi and Smith2019; Cohen Reference Cohen1999; Jordan-Zachery Reference Jordan-Zachery2007). Moreover, by recognizing and appreciating Black Americans’ support for policies that comprise America’s “racialized system of social control,” this work nuances our understanding of the challenges facing those who advocate for reform of the country’s punitive regime (Alexander Reference Alexander2012).

To date, much of the existing literature focused on race and punishment ignores heterogeneity in Black Americans’ views, focusing instead on the attitudes and predilections of white Americans (but see Forman Reference Forman2017; Fortner Reference Fortner2015). This bias in our theoretical and empirical approach is not without consequence. Although we know a great deal about the structuring of white Americans’ attitudes toward punitive social policies, we know far less about the social and psychological factors that guide Black Americans’ attitudes toward the same.Footnote 3

I endeavor to fill this gap by presenting a theoretical and empirical case for taking stigma and the politics of respectability seriously in the study of Black public opinion.Footnote 4 Respectability, as first defined by historian Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, “emphasize[s] reform of individual behavior and attitudes both as a goal in itself and as a strategy for reform of the entire structural system of American race relations” (Reference Higginbotham1993, 187). I argue that this socially instrumental view of respectability—and the focus on behavior and comportment it engenders—helps explain Black Americans’ support for punitive policies that target group members. In advancing this argument, I explore the myriad ways that stigma shapes the politics of the stigmatized. In particular, I consider how Black Americans’ experiences in a deeply racialized––and racist––social system have given rise to a worldview that threatens racial group solidarity by helping to sustain support for public policies that disadvantage the group’s most marginalized and stigmatized members.

In service of the article’s underlying theoretical and normative claims, I develop a novel measure of respectability—the Respectability Politics Scale (RPS)—and survey diverse samples of Black Americans in two separate studies. The development of this new measure is an important innovation of the current project, but its construction is not merely of methodological consequence. The RPS allows us to examine—in some cases, for the first time—core features of respectability. For example, we can assess how widespread respectability is among Black Americans. We can also investigate the demographic, social, and psychological correlates of the measure, which allows us to examine various lay theories about which subsets of Black Americans are more likely to embrace the politics of respectability. This exercise has an additional benefit: it helps elucidate further the expected theoretical and empirical relationship between respectability and Black Americans’ punitive attitudes.

This project makes several significant contributions. First, it strengthens our understanding of identity’s influence beyond the context of intergroup conflict. In doing so, it exposes a set of intragroup dynamics that inspire a process of in-group policing and punishment that has received far less attention than it warrants from scholars of American politics. Moreover, the current research subjects a familiar and often discussed concept—the politics of respectability—to the theoretical and empirical rigor it deserves. Finally, the work nuances our understanding of race and punishment in the United States while providing a theoretical basis for making sense of similar phenomena in other contexts.

Black Support for Racialized Punitive Social Policies

The current project focuses on variation in Black Americans’ attitudes toward a particular class of social policies—what I refer to as racialized punitive social policies. These policies explicitly or implicitly target Black Americans (Nelson and Kinder Reference Nelson and Kinder1996) and seek to police, constrain, deter, or punish certain behaviors or practices, especially those that are negatively stereotyped. Some are criminal-justice related (e.g., capital punishment and three-strikes laws). Others are paternalistic social welfare policies that burden and discipline the poor (e.g., requiring welfare recipients to work, volunteer, or be drug tested). Still, others are policies implemented in workplaces, schools, or other settings that disproportionately affect Black workers or Black school children (e.g., restrictions on certain hairstyles or forms of dress). To be sure, various nuances may inform more particularized theoretical and empirical models than those on offer here. There are, after all, important distinctions between three-strikes laws and ordinances regulating sartorial choices. Setting these distinctions aside, however, this categorization recognizes that a central thread connects these otherwise distinct social policies: they are policies perceived to target racial in-group members and are punitive in form.Footnote 5

In attending to diversity in Black public opinion, some have focused, as I do here, on Black Americans’ commitments to different ideological perspectives that diverge in their explanations of the causes and consequences of racial inequality (e.g., Dawson Reference Dawson2001; Harris-Lacewell Reference Harris-Lacewell2004). Other accounts focus on Black elites’ role in shaping group members’ attitudes. Some have argued, for example, that conservative shifts in Black public opinion reflect the mainstreaming of Black politics and the sidelining of a more radical politics in favor of more moderate position taking (e.g., Gillespie Reference Gillespie2012; Harris Reference Harris2012; Tate Reference Tate2010). From this perspective, Black support for conservative policies, including racialized punitive social policies, is the consequence of a broader phenomenon in Black politics that advantages more moderate and conservative positions over their more radical and liberal counterparts.

More targeted theoretical interventions provide additional leverage for making sense of Black Americans’ attitudes toward racialized punitive social policies. Hancock (Reference Hancock2004) notes, for example, that some Black Americans, like their white counterparts, subscribe to individualistic, rather than structural, explanations of inequality that make them skeptical of government assistance (see also Kam and Burge Reference Kam and Burge2018). This view of inequality, coupled with—and rooted in—an embrace of race, class, and gender-based stereotypes that portray Black women as “welfare queens,” helps to create and sustain a welfare infrastructure that reflects a “rise of neoliberal paternalism” in poverty governance in the United States (Hancock Reference Hancock2004; Soss, Fording, and Schram Reference Soss, Fording and Schram2011). As Soss and colleagues write, this underlying ideology “valorize[s] self-discipline [and personal responsibility] as the sine qua non of freedom” (Reference Soss, Fording and Schram2011, 22). The paternalistic arm of this neoliberal logic, likewise, focuses on the disposition of individuals. Under this regime of neoliberal paternalism, the state, acting as a kind of “fatherly figure,” monitors and polices those it regards as incapable of making prudent decisions for themselves. Consequently, welfare recipients, allegedly for their benefit, are subjected to a host of burdensome requirements to qualify for and receive welfare assistance. Notably, the state implements these restrictive and punitive policies with buy-in from a diverse coalition of supporters, including some Black Americans who embrace the neoliberal logic that characterizes the provision of welfare benefits in the United States (see also Spence Reference Spence2012; Reference Spence2015).

The neoliberal and punitive logic we observe in the structuring of America’s welfare infrastructure is also a hallmark of the country’s criminal justice system—a system that disproportionately burdens the lives of Black Americans and Black men, in particular (Alexander Reference Alexander2012; Pettit Reference Pettit2012). Scholars have long documented white Americans’ support for this racialized and punitive system of social control (see, e.g., Gilliam and Iyengar Reference Gilliam and Iyengar2000; Peffley and Hurwitz Reference Peffley and Hurwitz2002). For example, we know that white Americans’ views on issues related to criminal punishment are, in large part, a function of their attitudes toward Black Americans (e.g., Soss, Langbein, and Metelko Reference Soss, Langbein and Metelko2003). At issue here is what accounts for Black Americans’ attitudes toward the same.

Existing accounts focused on Black Americans’ attitudes toward criminal justice policies highlight the duality of Black Americans’ thinking. As Tate notes in her consideration of Black public opinion on issues related to criminal justice, Black Americans’ “perception of racial injustice tends to push Blacks against harsh sentencing policies, including the death penalty, and in favor of programs to combat juvenile crime. Yet, at the same time, Blacks are disproportionately the victims of violent crime and homicide” (Reference Tate2010, 63). Scholars note that this unparalleled experience of violent crime (Miller Reference Miller2015) can motivate some to endorse punitive crime policies (Costelloe, Chiricos, and Gertz Reference Costelloe, Chiricos and Gertz2009). As a review of this literature clarifies, however, concerns about safety and security often exist alongside concerns that negatively stereotyped criminal behavior threatens the group’s collective goals and, therefore, must be punished.

Among the most prominent accounts of Black Americans’ support for criminal punishment are Fortner’s (Reference Fortner2015) Black Silent Majority and Forman’s (Reference Forman2017) Locking up Our Own. Fortner’s analysis focuses on Black support for implementing harsh drug laws in New York in the 1970s. When they were signed into law by Republican Governor Nelson Rockefeller, the so-called Rockefeller Drug Laws were among the most punitive drug laws in the country. If convicted, individuals charged with selling or possessing drugs could face a mandatory minimum sentence of 15 years in prison to life imprisonment. As Fortner notes, “The proposed drug laws had stoked the ire of white liberals” who saw them as “ideologically unpalatable and inconsistent with their understanding of this policy problem” (Reference Fortner2015, 2). However, working-class and middle-class Black Americans had grown skeptical of “softer” attempts to respond to drug use and violence in their communities. Instead, they viewed more punitive measures as necessary responses to the spate of crime and violence they experienced in their neighborhoods. Notably, however, support for these more punitive measures was not merely a reaction to real or perceived threats of violence. It was also rooted in a belief that those engaged in the drug trade and other criminal behavior were threats to middle-class values and morals. As such, they existed outside the boundaries of the “broader class-based community of ‘decent citizens,’ ‘hardworking people,’ and Bible-believing churchgoers” (Fortner Reference Fortner2015, 170).

Similar arguments emerge in Forman’s analysis of why tough-on-crime measures took hold in cities led by Black elites. These elites—some of whom had previously taken part in the Civil Rights Movement—understood the structural inequities that plagued the criminal justice system. Nevertheless, when faced with calls from middle-class Black residents to do something about crime and violence, these same Black elites advocated for implementing and enforcing various tough-on-crime policies. These policies included marijuana prohibition, mandatory minimums for drug and gun-related crimes, and increased surveillance of poor and working-class Black people. However, many Black elites saw little contradiction in supporting tough-on-crime policies while also espousing support for the Civil Rights Movement and other justice-focused efforts. Group members who engaged in criminal behavior were, after all, according to these elites, “betraying King’s dream” and undermining the work of civil rights activists who had worked hard to advance the collective goals of the racial group (Forman Reference Forman2017, 195). They had, in essence, run afoul of the values of respectability and were seen as deserving of punishment, not group solidarity.Footnote 6

Respectability: “A Dominant Framework”

The “politics of respectability” was first used to describe a worldview adopted by Black women who were part of the women’s movement in the Black Baptist Church during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (Higginbotham Reference Higginbotham1993). Respectability’s adherents had two primary motivations. First, they “emphasized reform of individual behavior and attitudes as a goal in itself.” Second, they viewed respectability “as a strategy for reform of the entire structure of American race relations” (Reference Higginbotham1993, 187). Regarding the first motivation, advocates of respectability viewed good behavior as morally right and prudent and consistent with middle-class values and sensibilities. On the other hand, negatively stereotyped behavior was considered unbecoming and detrimental to the goal of racial self-help, independent of the white gaze (see also Gaines Reference Gaines2012).

Respectability’s adherents were also motivated by a more strategic consideration. If Black people wanted white people to treat them better, advocates of respectability argued, they needed to show themselves worthy of equality by abandoning behaviors that confirmed negative racial stereotypes. An allegiance to “dominant society’s norms of manners and morals,” advocates of respectability believed, would “counter racist images and structures,” thus helping to usher in a more equitable situation for Black Americans (Higginbotham Reference Higginbotham1993, 187).

The current research focuses primarily on this second motivation—the concern that negatively stereotyped behavior frustrates the group’s goal of achieving racial equality. In thinking carefully about this concern, the work complicates a more prosocial rendering of respectability by highlighting how concerns about the white gaze and a general embrace of respectability politics undermine racial group solidarity and help sustain a system of punishment that disproportionately bears on the group’s most stigmatized members.

By taking on this perspective, the current research draws the reader’s attention to what the political theorist Desmond Jagmohan recognizes as a kind of “tragic realism” that often befalls those forced to live under regimes of oppression (Reference Jagmohan2015). Faced with the reality of discrimination and subjugation, members of marginalized groups often feel compelled to adopt strategies they believe will improve their collective lot. For the Black Baptist women whose lives Higginbotham documents, respectability acted as such a strategy, just as it has, across time, for those who belong to other marginalized groups (see, e.g., Strolovitch and Crowder Reference Strolovitch and Crowder2018). The tragedy, however, lies in the reality that a political strategy based in respectability “can risk redrawing rather than erasing the boundaries of intersectional and secondary marginalization” (Reference Strolovitch and Crowder2018, 341).Footnote 7 Put differently, respectability’s benefits can come at great cost to those already living closest to the margins.Footnote 8

In political science, few have been more attentive to the potential costs of respectability for marginalized in-group members than Cathy Cohen, whose research has long highlighted respectability as a “dominant framework” in Black politics (Reference Cohen2004). In her pioneering text Boundaries of Blackness (Reference Cohen1999), Cohen documents how an embrace of respectability politics undermined group-based solidarity for Black victims of the AIDS crisis and, in doing so, “cast doubt on the idea that a shared group identity and feelings of linked fate can lead to the unified group resistance or mobilization that has proved so essential to the survival and progress of [B]lack and other marginal people” (13).

In more recent work, Bunyasi and Smith (Reference Bunyasi and Smith2019) leverage Cohen’s notion of secondary marginalization and insights from scholars of intersectionality (e.g., Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw1990; Jordan-Zachery Reference Jordan-Zachery2007) to provide a quantitative assessment of how respectability affects the perceived importance of cross-cutting issues that affect specific segments of the group. Consistent with their theoretical expectations, the authors find that Black respondents who embrace respectability politics are more likely to deprioritize issues affecting Black women, formerly incarcerated Black people, Black undocumented immigrants, Black gays and lesbians, and Black transgender people.Footnote 9 These findings are noteworthy because they represent one of the most direct quantitative treatments of respectability to date. They are wholly in line, however, with the expectations of qualitative and historical accounts that document the powerful role respectability plays in affecting all aspects of Black political and social life—from the portrayal and focus of social movements (e.g., Alexander-Floyd Reference Alexander-Floyd2007; Fackler Reference Fackler2016) to the evaluations of Black women’s bodies (e.g., Brown and Young Reference Brown, Young, Mitchell and Covin2016) and the treatment of Black LGBT people (e.g., Wadsworth Reference Wadsworth2011).

The current research builds on this work while grounding the politics of respectability more explicitly in a social psychological framework that is attentive to the historical and social context the existing literature so impressively documents. This approach serves dual purposes. First, it allows us to examine the workings of social identities that give rise to in-group policing, broadly, and the politics of respectability, more specifically. Moreover, this approach, which adopts a complex and nuanced view of identity, helps to clarify, in theoretically grounded and empirically testable ways, the relationship between respectability and Black Americans’ punitive attitudes. Underlying this approach is the expectation that at the heart of respectability politics and Black Americans’ punitive attitudes are identity-based concerns that have not been adequately explored in previous work.

Respectability Politics as a Social Psychological Phenomenon

Social identities give us a sense of who we are and what our value is in the social world (Tajfel and Turner Reference Tajfel, Turner, Worchel and Austin1986). Because they affect our self-esteem, we are motivated to maintain a positive image of our social groups and are concerned when the group’s identity is devalued. This concern is even more pronounced for members of stigmatized groups, as group members are forced to engage and navigate threats to their social identity more frequently (Major and O’Brien Reference Major and O’Brien2005). As a result, those who belong to stigmatized groups employ various strategies to deal with and respond to potential identity threats. Importantly, these threats can be external to the group (Lyle Reference Lyle2015; Pérez Reference Pérez2015) or can be perceived as emerging from within—the consequence of individual group members’ behaviors or ways of being (Lewis and Sherman Reference Lewis and Sherman2003; Taylor et al. Reference Taylor, Garcia, Shelton and Yantis2018).

Group Identities and Collective Threats

Consistent with claims that individual identities are linked to group identities, “individual psychology is affected by collective outcomes” (Cohen and Garcia Reference Cohen and Garcia2005, 566). “Collective threats,” as Cohen and Garcia (Reference Cohen and Garcia2005) regard them, “issue from the awareness that the poor performance of a single individual in one’s group may be viewed through the lens of a stereotype and may be generalized into a negative judgment of one’s group” (566). These concerns about collective threats emerge in various contexts and manifest across domains. They are also likely evoked by the kinds of stereotype-confirming behavior at issue here. Moreover, these perceived threats to the group’s identity can provoke emotional responses and bring to the fore concerns about collective costs—perceived emotional or material costs the group may incur given the actions of individual group members.

The Emotional Substrates of Respectability

Because collective threats implicate individuals’ sense of who they are, individuals may experience shame or other self-directed emotions in the face of perceived threats to the group’s image. Shame is a complex social emotion involving disgrace or dishonor (Lewis Reference Lewis, Tangney and Fischer1995). To experience shame, one must be aware of the expectations and standards in a given context and have the capacity “to evaluate the self with regard to those standards,” and know when one has fallen short (Lewis Reference Lewis, Tangney and Fischer1995, 68). As is the case with individual experiences of shame, experiences of group-based shame go beyond recognizing that what some group member has done is bad. Instead, feelings of group-based shame reflect a sense that, due to some transgression, the group is bad and will be judged harshly by relevant others (Gilbert Reference Gilbert, Gilbert and Andrews1998). For example, Burge and Johnson (Reference Burge and Johnson2018) find that Black Americans report higher levels of group-based shame when exposed to news stories that discuss “Black on Black crime,” as such stories highlight negative, stereotype-confirming behavior by in-group members. The confirmation of these negative stereotypes threatens the group’s image, thereby serving as a potential threat to the esteem of individual group members. Working alongside shame, feelings of in-group-directed anger may also condition the likelihood that individuals embrace a worldview that punishes those who violate social norms or threaten the group’s image. Individuals experience anger when they can blame another person for a particular outcome and perceive that the action in question was unjustified or unwarranted (Griffin et al. Reference Griffin, Yang, Ter Huurne, Boerner, Ortiz and Dunwoody2008; Petersen Reference Petersen2010).

Emotions have social functions (Keltner and Gross Reference Keltner and Gross1999). In the case of shame, it warns that one is “socially unacceptable” and deters one from engaging in shame-inducing behavior in the future. Therefore, the experience of group-based shame may motivate group members to correct or punish shame-inducing behavior within the group. Anger, too, has a social function. It moves individuals to action (Banks Reference Banks2014; Scott and Collins Reference Scott and Collins2020; Valentino and Neuner Reference Valentino and Neuner2017). Therefore, we should expect those who experience more in-group-directed anger in reaction to public views of the group to be more likely to adhere to respectability, given its advocacy for responding to and doing something about transgressive behavior (see Iyer, Schmader, and Lickel Reference Iyer, Schmader and Lickel2007).Footnote 10

Respectability’s Instrumental Roots

Social identities do more than confer a sense of psychological connection to salient social groups; they orient and affect our place in the social world. Identities, after all, are not merely of psychological origin or consequence. They are politically, socially, and historically situated and exist along hierarchies of privilege and subjugation. Consequently, individuals—particularly those who belong to stigmatized social groups—do not merely worry that the behavior of in-group members will bring about aversive emotions like shame or embarrassment. Identities structure real and tangible outcomes that make life better or worse, depending on which side of the stratification one exists (e.g., Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw1990). So, just as emotional considerations may motivate individuals to police the behavior of similar others as a means of avoiding negative emotions, we should expect that more instrumental and tangible considerations matter, too (see, e.g., Lewis and Sherman Reference Lewis and Sherman2003).

With few exceptions (e.g., Bedolla Reference Bedolla2003), concerns about the instrumental nature of collective threats are noticeably absent in political science accounts of social identities. However, the historical record provides many reasons to take seriously the possibility that individuals, when rendering judgments about in-group members’ behavior, consider the likelihood that these actions will have cascading consequences for the group. Harris-Perry (Reference Harris-Perry2011) notes, for example, that “Southern lynch mobs and Northern White race riots made no allowance for the innocent [Black] people in the path of their murderous hunts for ‘Black criminals’” (Reference Harris-Perry2011, 117–8). Dawson (Reference Dawson1994) similarly argues that it is rational for Black Americans to use the group’s status as a proxy for their own given the indiscriminate nature with which Jim Crow laws and informal sanctions affected Black people, irrespective of their particular circumstances. Furthermore, in detailing the emergence of “secondary marginalization” among Black Americans, Cohen (Reference Cohen1999) highlights the belief that an airing of the group’s “dirty laundry” would make it more difficult for Black people aspiring to incorporate into the mainstream and more powerful echelons of society.

As this existing research makes clear, the politics of respectability does not emerge independent of a continued system of white supremacy in the United States. Instead, understood in this context, respectability reflects an unequal social hierarchy wherein members of stigmatized groups understand that the circumstances of their own lives are determined not simply by the choices they make but also by the choices and behaviors of similar others. In this way, the instrumental concerns that ground the politics of respectability are akin to those in Fearon and Laitin’s (Reference Fearon and Laitin1996) work that describes in-group policing as a strategy for maintaining comity between opposing groups. In the case of Black Americans, those who embrace respectability politics believe that white Americans will reward group members’ good behavior; consequently, the lot of the group will improve.

Theory and Argument

Black Americans belong to a stigmatized social group in American society. Thus, individual group members have long faced threats of indiscriminate harm, violence, and social judgment because of their racial identity. Aware of the stratified nature of the social hierarchy in the United States, some Black Americans embrace a view of the social world that centers group members’ behavior in their thinking about racial inequality. Consistent with Higginbotham’s (Reference Higginbotham1993) historical account of Black women active in the women’s movement in the Black Baptist Church, these Black Americans believe that if group members behave better and carry themselves better, society will treat Black people better. This embrace of respectability, I argue, is, at its core, a social psychological phenomenon with significant political implications, particularly as it relates to Black Americans’ views regarding issues of punishment that implicate group members.

Within this framework, group members view negatively stereotyped behavior as threatening to the image of the social group, which, consequently, is threatening to the self (Tajfel and Turner Reference Tajfel, Turner, Worchel and Austin1986). Moreover, negatively stereotyped behavior is perceived to threaten the already-precarious status of the group and is viewed as a challenge to collective goals of racial uplift (Gaines Reference Gaines2012). Consequently, those who hold these beliefs—adherents of respectability politics—worry about fellow group members’ behavior and, therefore, support policies that punish or restrict negatively stereotyped behavior. Consistent with this view of respectability politics as a worldview rooted in identity-based concerns, I expect the following:

First, I expect respectability will correspond with in-group-directed shame and anger. Those who feel more ashamed or angry about how others view the group should be more willing to embrace a worldview that directly focuses on deterring and correcting negatively stereotyped behavior. Second, I also expect those who score higher on measures of linked fate will more strongly embrace the politics of respectability, given their sense that what happens to the group will affect their own lives. This expectation is a test of the instrumental roots of respectability politics. Likewise, I expect adherents of respectability will be more likely to distance themselves from the racial group. Finally, I also expect adherents of respectability to discount discrimination’s role in structuring group outcomes.

A priori assumptions about the nature of respectability suggest that higher-income Black Americans may be more likely to embrace the worldview given its reflection of middle-class values and sensibilities. I am skeptical of this expectation, despite conventional wisdom that respectability is the politics of the bourgeois. Black Americans, irrespective of their class position, are exposed to various institutional and societal forces that privilege the politics of respectability as a strategy to upend systems of racial oppression. These forces, including the Black church, can play a critical role in shaping marginalized group members’ beliefs, even if the ideology they advance is disadvantageous for these group members.Footnote 11 Therefore, I do not expect that various demographic factors, such as age, class, and gender, will condition Black Americans’ embrace of respectability politics, especially after accounting for other social and psychological factors. However, I do expect that more religious Black Americans will more strongly embrace respectability. As Higginbotham notes, the Black church often preaches the politics of respectability (Reference Higginbotham1993). The Victorian ethos of respectability also closely corresponds with values and norms advocated for by religious institutions (see, e.g., Jagmohan Reference Jagmohan2015; Patton Reference Patton and Bambara1970). Likewise, I expect adherents of respectability to be generally more concerned about order and conformity than those who reject the worldview. Thus, I expect adherents to score higher on a standard measure of authoritarianism, which captures these more general dispositions.

Critically and in line with the expectations outlined above, I expect those high in respectability will be more supportive of policies that punish in-group members who engage in negatively stereotyped behavior. I expect this relationship to persist even after accounting for respondent-level differences in partisanship, ideology, authoritarianism, linked fate, and demographic controls. Moreover, I expect, ceteris paribus, that respectability will correspond with individuals’ reactions to various scenarios in which group members engage in negatively stereotyped behavior.

Data and Methods

To test the expectations regarding respectability and its relation to Black Americans’ punitive attitudes, I contracted with Qualtrics Panels in April 2019 to survey a diverse sample of 500 Black Americans. Respondents skew a bit older, but approximately a quarter of the sample is between 18 and 34 years old. The sample is also disproportionately female, so all analyses include controls for age, sex, education, income, and region.Footnote 12 I present sample characteristics in online Appendix A. I present the primary variables and their coding in online Appendix B. See the online supplementary material for the complete study protocol.Footnote 13

Measuring Respectability

To date, our understanding of respectability—and the role it plays in the social and political lives of Black Americans—is based almost solely on historical and qualitative accounts (e.g., Kerrison, Cobbina, and Bender Reference Kerrison, Cobbina and Bender2018). Although these accounts help ground our understanding of respectability, they leave unanswered important questions regarding its roots and consequences for American politics. Scholars who have adopted more quantitative approaches to study respectability have relied on analytical strategies that attempt to circumvent a fundamental challenge: there is, to date, no measure of the concept (e.g., Board et al. Reference Board, Spry, Nunnally and Sinclair-Chapman2020; Bunyasi and Smith Reference Bunyasi and Smith2019). The lack of a valid measure of respectability does more than present a practical inconvenience for researchers. It imperils scholars’ ability to answer important theoretical questions and makes it challenging to answer a host of first-order questions about the nature of respectability itself.

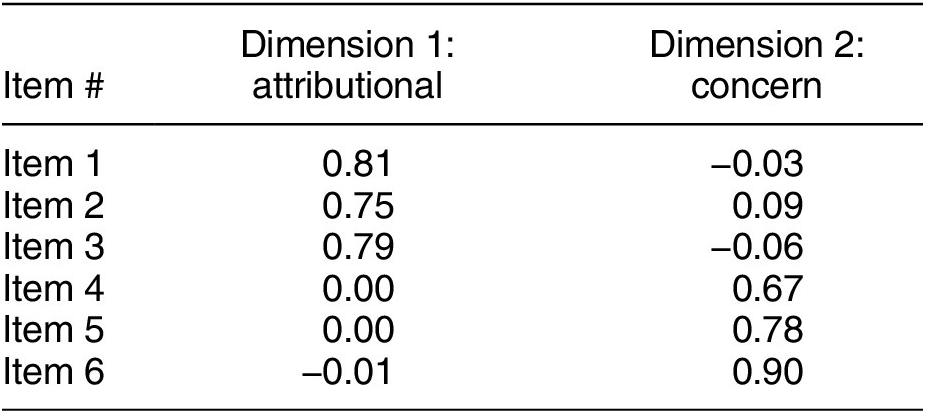

To fill this void, I develop the Respectability Politics Scale (RPS), a composite measure comprised of two subscales that measure (1) individuals’ beliefs that Black behavior is to blame for the status of the group in society and (2) one’s level of concern about in-group behavior. The subscales are each measured using a battery of three agree–disagree items (refer to Table 1). The first subscale of the RPS (items 1–3) captures individuals’ sense that the group’s fortune depends on group members’ behavior. We can think of this as the attributional arm of respectability that captures variation in individuals’ embrace of some quid pro quo understanding of equality. Working synchronously with this arm of respectability is individual-level variation in concern about the behavior of in-group members. That is, to what extent does an individual Black person care about how fellow group members behave? I call this the concern arm of respectability (items 4–6).

Table 1. Respectability Politics Scale

Note: Strongly Disagree–Strongly Agree.

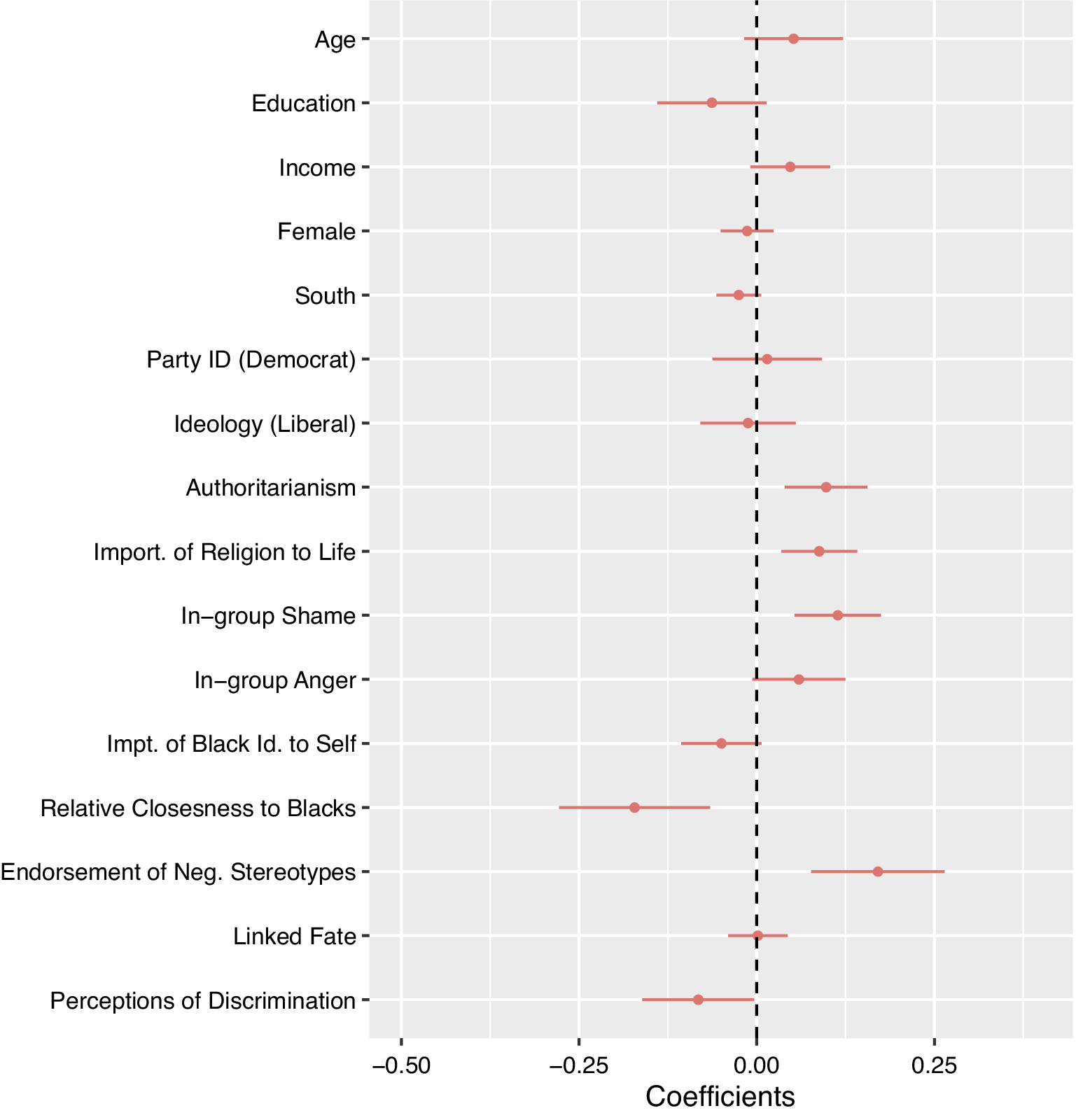

To begin, I examine the dimensionality of respectability described here. Using a factor analytic approach, I set out to demonstrate that the items of the RPS cohere in a manner consistent with the theoretical grounding of the construct. The factor analysis results, using pro-max oblique rotation, are shown in Table 2. Findings indicate that the six items fall along two dimensions, which correlate at r = 0.26. This factor structure is consistent with the theoretical view of respectability that defines the construct as reflecting both an individual’s sense that behavior matters in affecting group outcomes and individuals’ more general concerns regarding in-group behavior that may manifest for reasons independent of the white gaze. Though we observe that the two dimensions of respectability are somewhat orthogonal, we are interested here in the influence of the overall construct and less so in the independent work of the two dimensions.Footnote 14 Thus, I construct a composite measure of respectability—the Respectability Politics Scale. The RPS is a sum of respondents’ scores on the attributional subscale (α = 0.83) and scores on the concern subscale (α = 0.82).Footnote 15

Table 2. Factor Structure of Respectability Politics Scale

Note: 2019 Qualtrics panel data; results presented are from a factor analysis using pro-max oblique rotation.

The 6-item RPS has a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.77, suggesting high levels of internal consistency among the items. Figure 1 also shows that the scores on the RPS are normally distributed among respondents. When standardized from 0 to 1, with higher scores indicative of a stronger embrace of respectability, the mean and median scores are 0.56. Looking at those who score one standard deviation below and above the mean score on the RPS, approximately 12% of the sample is low in respectability. Approximately 19% is high in respectability. The remainder of the sample falls somewhere in between. I present these descriptive statistics to provide context for understanding scores on the RPS, but I leverage the full spread of scores in all analyses.Footnote 16

Figure 1. Distribution of the Respectability Politics Scale

Note: 2019 Qualtrics panel data; RPS scores recoded 0–1, with higher values indicating a stronger embrace of respectability politics.

Who Embraces the Politics of Respectability?

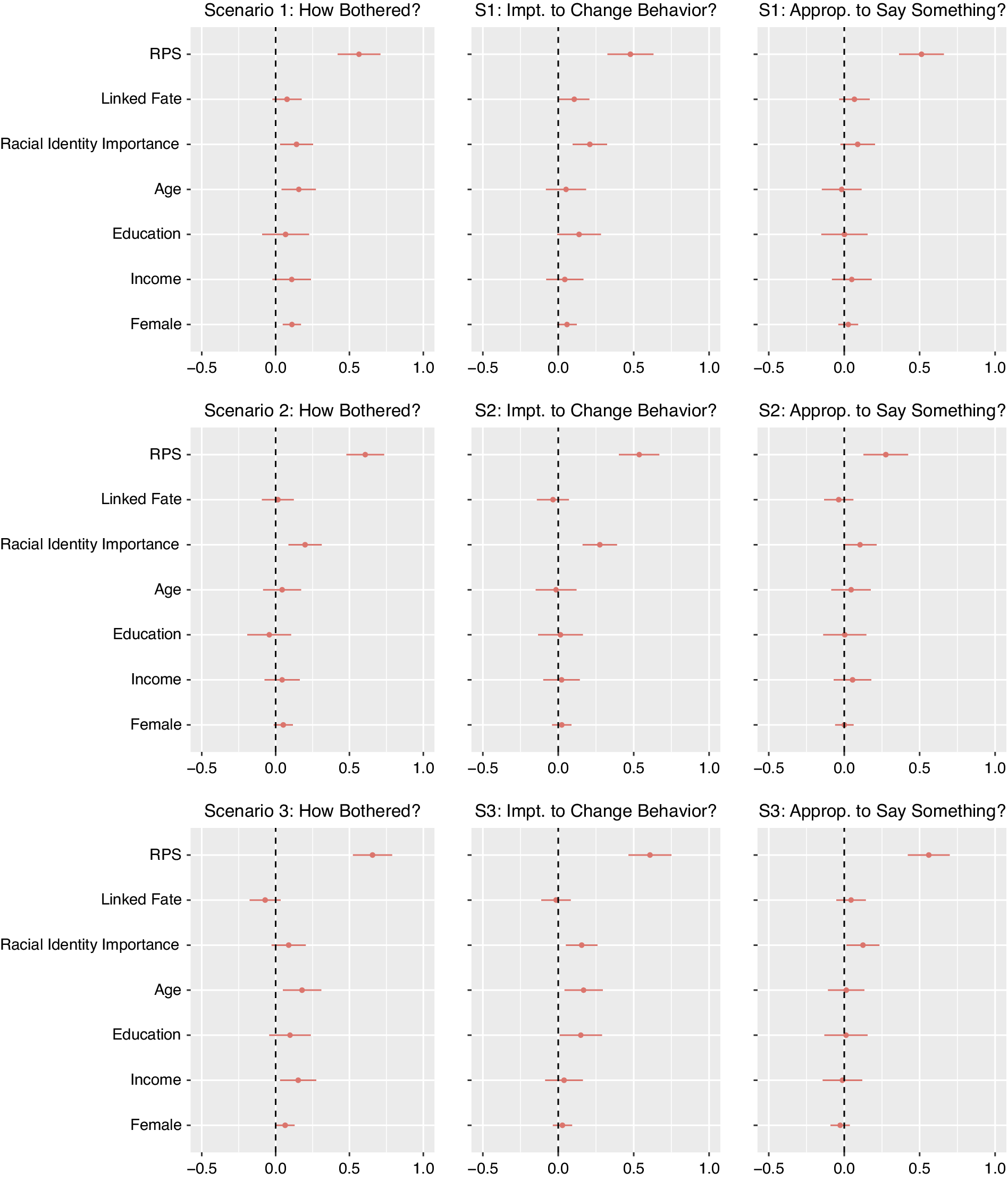

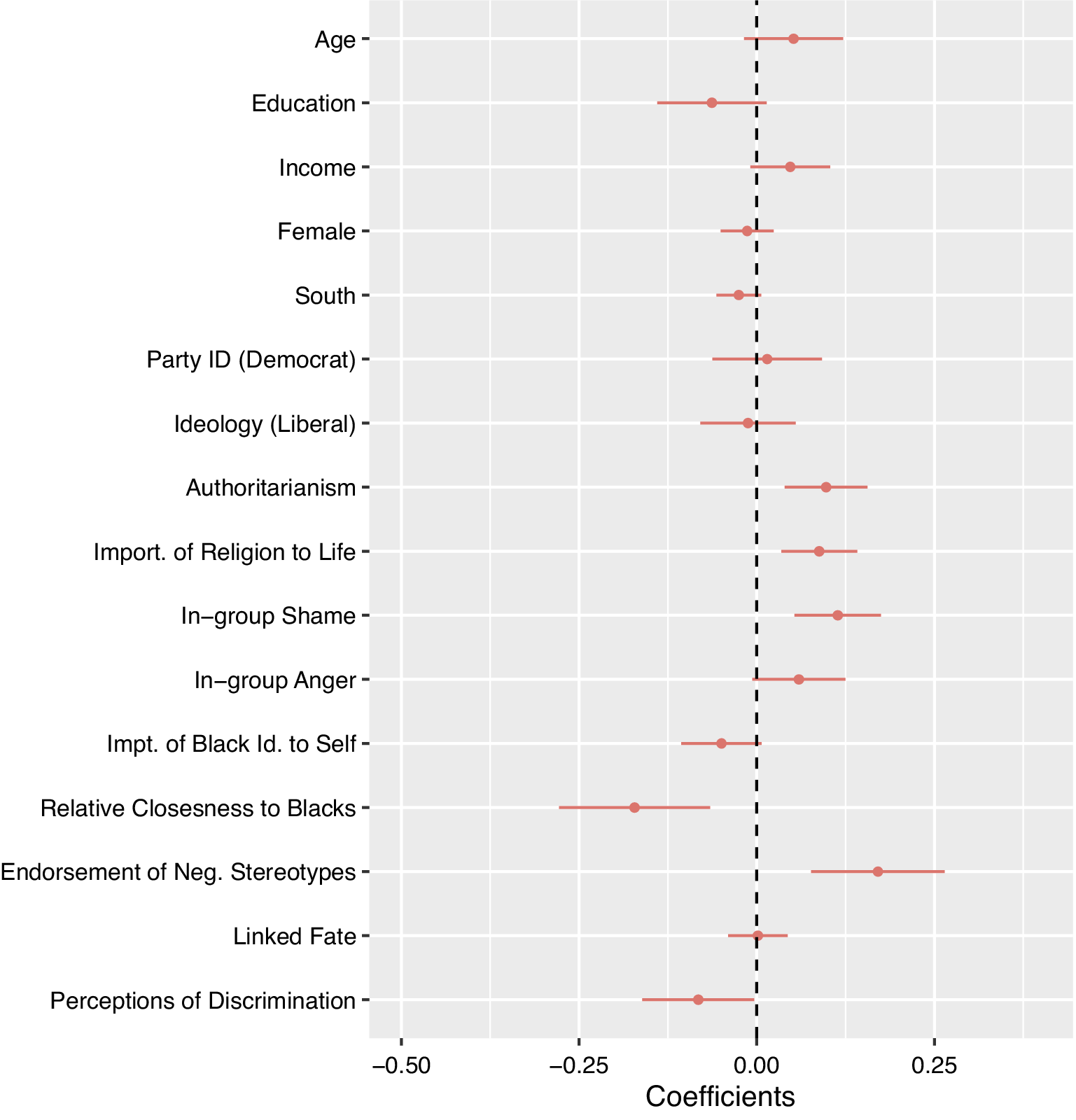

Moving next to considering who embraces respectability politics, I run a multivariate regression model with the RPS as the main outcome variable of interest (refer to Figure 2). Regarding the various demographic variables included in the model, we find scant evidence that variation in respondents’ embrace of respectability reflects age, education, class, gender, or geographic differences. For example, lower-income Black Americans are almost just as likely to embrace respectability politics as are their upper-income counterparts. Black men are also just as likely to embrace respectability as are Black women. There is also no strong evidence that geography matters much in shaping Black Americans’ embrace of respectability politics. Likewise, we find no evidence that beliefs about respectability break down along partisan or ideological lines such that adherents are more likely to identify as Republican or as conservative.Footnote 17

Figure 2. Who Embraces the Politics of Respectability?

Note: 2019 Qualtrics Panel data; standardized regression coefficients and 95% confidence intervals plotted from multivariate OLS model. All variables recoded 0–1. A corresponding regression table is included in online Appendix F.

However, we observe that respondents who score high on the standard measure of authoritarianism, asking individuals about their child-rearing preferences, are more likely to embrace respectability (p < 0.01). Notably, authoritarianism only moderately correlates with the RPS (r = 0.25), suggesting that this broader behavioral disposition differs from respectability. The concepts also have distinct predictors, further evidence of the concepts’ unique features.Footnote 18 Likewise, adherents of respectability also report that religion is more important to their lives (p < 0.01). This finding suggests—consistent with Higginbotham’s historical account—that the Black church plays an influential role in sustaining and advancing the politics of respectability. Although the current data do not allow us to query further, the relationship between the RPS and religiosity may also reflect the fact that Victorian sensibilities that are central to the politics of respectability are also central to many Black Americans’ religious commitments.

In addition to these demographic factors, other social and psychological measures help to clarify the social psychological nature of respectability politics. Insofar as the politics of respectability is bound up with identity-based concerns, as discussed previously, measures of individuals’ feelings about the racial group should correspond with their placement on the RPS. Of note, there is no correspondence between identity centrality (i.e., the importance of racial identity to the self) and respondents’ scores on the RPS. However, we observe that Black respondents who feel closer to other Black people, relative to how close they feel to white people, are less likely to embrace respectability (p < 0.01). Moreover, those who more strongly embrace respectability politics are more likely to endorse negative stereotypes about the group. Adherents of respectability are more likely to believe that in-group members are violent, less hardworking, less intelligent, and contribute to a negative image of the racial group (p < 0.001). Likewise, when asked how often they feel ashamed when they think about how others view the group, those who score higher on the RPS are more likely to say that they frequently experience this negative group-based emotion (p < 0.001). However, we do not observe a significant relationship between in-group-directed anger and respectability, though the relationship trends in the expected direction. As expected, perceptions of discrimination negatively correspond with scores on the RPS. Individuals who perceive more discrimination toward Black people in the United States are less likely to embrace respectability politics.

To proxy for the kind of instrumental considerations that are potentially at work in Black Americans’ thinking about respectability, I include a measure of linked fate, which captures variation in individuals’ beliefs that what happens to the group will affect their own lives (Dawson Reference Dawson1994). Theoretically, we should expect that individuals who have a heightened sense of linked fate would be more likely to endorse respectability, given that individual group members’ behavior could have cascading consequences for the whole. Interestingly, no such relationship emerges in the data, though linked fate may be an inadequate proxy for perceptions of collective costs as described in this article. I return to this point when discussing future directions inspired by the current project.

Relationship between Respectability and Black Americans’ Punitive Attitudes

Now that we have a sense of who embraces respectability, our focus turns to whether scores on the RPS meaningfully correspond with attitudes toward racialized punitive social policies. At the start of the survey, participants responded to a series of policy questions. Some of these policies ought to be theoretically associated with respectability. Yet, at the same time, we should find no correspondence with certain attitudes like individuals’ beliefs about the role of government in responding to climate change, for example.

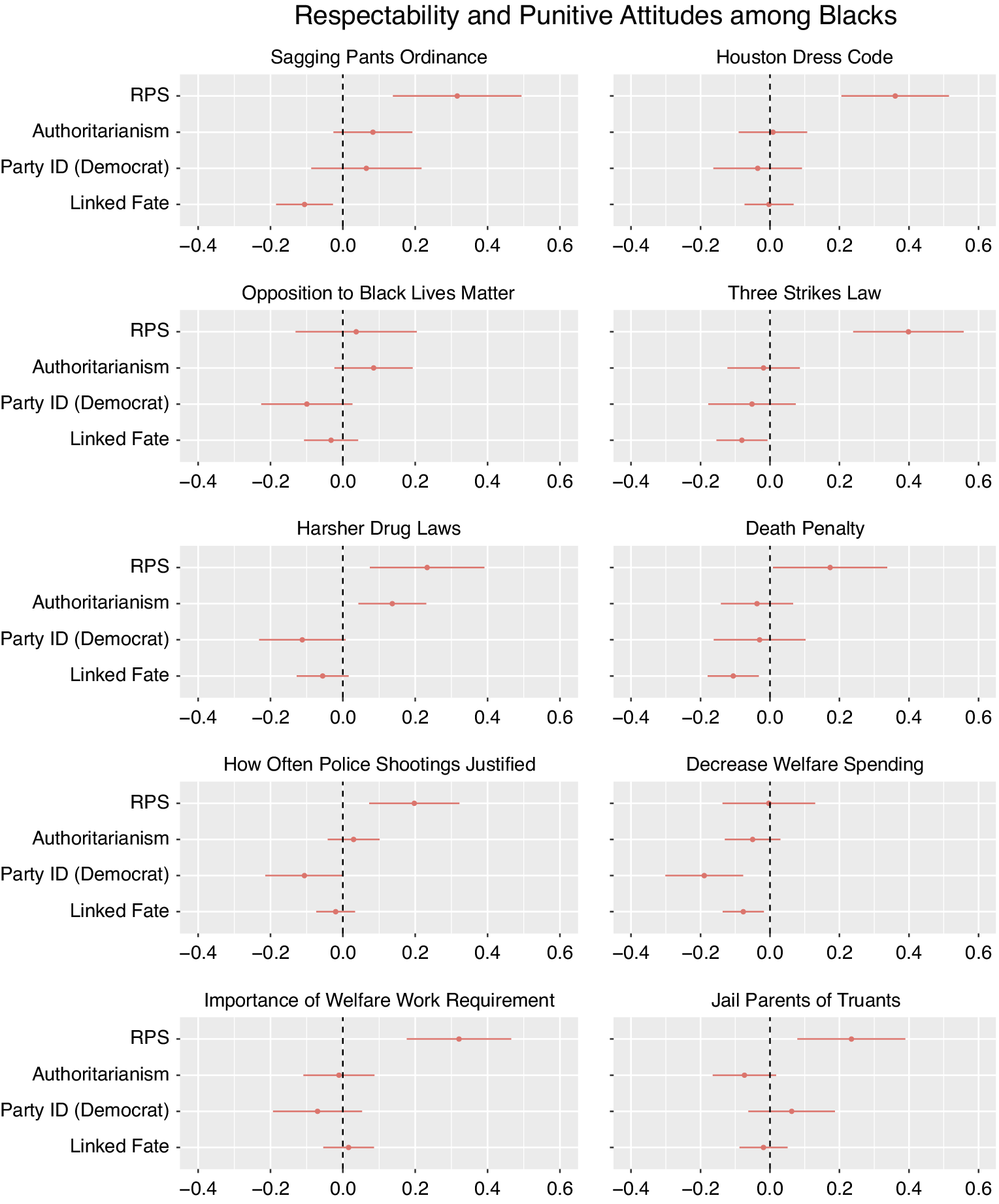

I begin with two questions that ask respondents their beliefs about policies that regulate how individuals carry themselves in public. First, returning to the case at the start of the article, I consider respondents’ beliefs about the appropriateness of ordinances that fine individuals for sagging their pants in public. Here, we find that higher scores on the RPS strongly correspond with support for these ordinances (p < 0.001). Likewise, when asked to opine on a Houston high school policy that policed what parents could wear when doing business at the school, we find that respectability is the chief predictor of attitudes toward this controversial policy (p < 0.001).Footnote 19

Similarly, when asked about broken-windows-style policies that allow law enforcement officers to stop those who are loitering, trespassing, or engaged in disorderly conduct, we again see a strong relationship between respectability and Black Americans’ attitudes (p < 0.001). Those at either extreme of the RPS differ by approximately 24 percentage points. We find similar patterns when we examine Black attitudes toward three-strike laws (p < 0.001), harsher sentences for violations of the nation’s drug laws (p < 0.05), and support for the death penalty (p < 0.05). In each case, those who more strongly embrace the politics of respectability are more likely to adopt the more punitive position. These results maintain even after accounting for variation in individuals’ partisanship, ideology, attachment to the racial group, and general beliefs about order and conformity as captured by a measure of authoritarianism. Furthermore, I ask respondents about one of the most pressing issues of the day—police use of force in encounters with Black Americans. Here we find that those who more strongly embrace the politics of respectability are more likely to respond that police shootings of Black Americans are—at least sometimes—justified (p < 0.01).

However, respectability’s influence is not limited to these criminal-justice-related policies. Although we observe no relationship between the RPS and attitudes regarding increased welfare spending, those high in respectability are more likely to support regulating the behavior of welfare beneficiaries. Adherents of respectability are more likely to think it appropriate to require that welfare beneficiaries work or volunteer while receiving the benefit, a policy in keeping with President Bill Clinton’s 1996 reform of the welfare system (p < 0.001). Moreover, we observe that respectability is associated with other beliefs among Black respondents, including beliefs about controversial truancy policies that threaten to jail parents whose children miss several days from school for no reason. Those who embrace respectability politics are much more likely to endorse putting these parents in jail (p < 0.01). See Figure 3 for a complete presentation of results related to these analyses.

Figure 3. Respectability Politics Scale Predicts Punitive Attitudes

Note: 2019 Qualtrics Panel data; standardized regression coefficients and 95% confidence intervals plotted from multivariate OLS model. In addition to the variables displayed, all models include the following: ideology, age, income, education, sex, and region. All variables recoded 0–1. Corresponding regression tables are included in online Appendix G.

Notably, respectability is not significantly related to Black Americans’ attitudes about whether the government should increase immigration levels or whether the government should do more in response to climate change. This lack of correspondence with attitudes unrelated to punitive policies that target the in-group further demonstrates the measure’s validity. Theoretically, respectability politics should be directed at the racial in-group, not out-groups, and should not shape attitudes on nonracial issues.

Respectability and Reactions to Real-World Scenarios

Beyond its role in predicting individuals’ policy preferences, we should observe, too, that respectability affects how individuals react to situations involving the behavior of in-group members. To test this expectation, I conducted a separate study in August 2019 using TurkPrime Panels, a platform that allows researchers to sample from “more than 30 million participants worldwide.”Footnote 20 In many respects, TurkPrime is like other survey outlets that draw from various participant databases and advertisements. However, unlike the standard Mechanical Turk platform, TurkPrime Panels recruits participants beyond the Mechanical Turk worker base, which helps generate a pool of respondents who are less frequent survey takers and more representative of the population than the smaller pool of MTurk workers. Using TurkPrime Panels also allows the researcher to target specific respondents, which helps generate a sample of Black respondents, which would be challenging to do using the standard MTurk platform (see Litman, Robinson, and Abberbock Reference Litman, Robinson and Abberbock2017 for a broader discussion of TurkPrime).Footnote 21

The sample recruited for the current project includes 300 Black Americans. The median age of the sample is between 35 and 44 years of age. Fifty-eight percent of the sample is female, and the median respondent has “some college.” Though this is not a representative sample of Black Americans, the point of the analyses presented in this section is to engage in hypothesis testing regarding a possible relationship between respectability and reactions to everyday situations. Thus, we are less interested in any particular point estimate in the general population, and all models include demographic controls to account for imbalance along various dimensions of the sample.

At the start of the survey, respondents were told, “we are interested in how Black Americans respond to various everyday situations.” All respondents answered a set of questions about their racial identification before being introduced to three different scenarios, presented in random order. Following their responses to questions about the scenarios, respondents completed the Respectability Politics Scale items and other demographic questions. Below are the three scenarios that respondents engaged in the study.

-

1. Imagine that you are dining at a fancy restaurant where you are one of few Black customers. You look over and see that two other Black people are dining near you. Throughout dinner, you hear them cursing at each other, using the N-word, and repeatedly complaining loudly about their food to the server.

-

2. Imagine you work at a company with mostly White coworkers. One day, the company hires a new employee who happens to be Black. She shows up to work late, doesn’t pay attention during meetings, and takes more breaks than other coworkers. When asked to complete a task, she often makes mistakes or takes far longer than she should.

-

3. Imagine you’re at a recreation center in the suburbs with your family. During your visit, another group of Black people walks in. They are playing loud, explicit music and start to play around aggressively in the pool, drawing a lot of attention from those nearby.Footnote 22

Following each scenario, respondents were asked three questions: “How bothered are you by this behavior?”; “How important is it to you, personally, that [the individuals in the scenario] change their behavior?”; and “How appropriate would it be for someone to say something to [the individuals in the scenario] about their behavior?” These three variables are coded such that higher values indicate a more negative reaction to the behavior in question (e.g., being more bothered). See online supplementary material for complete study protocol.

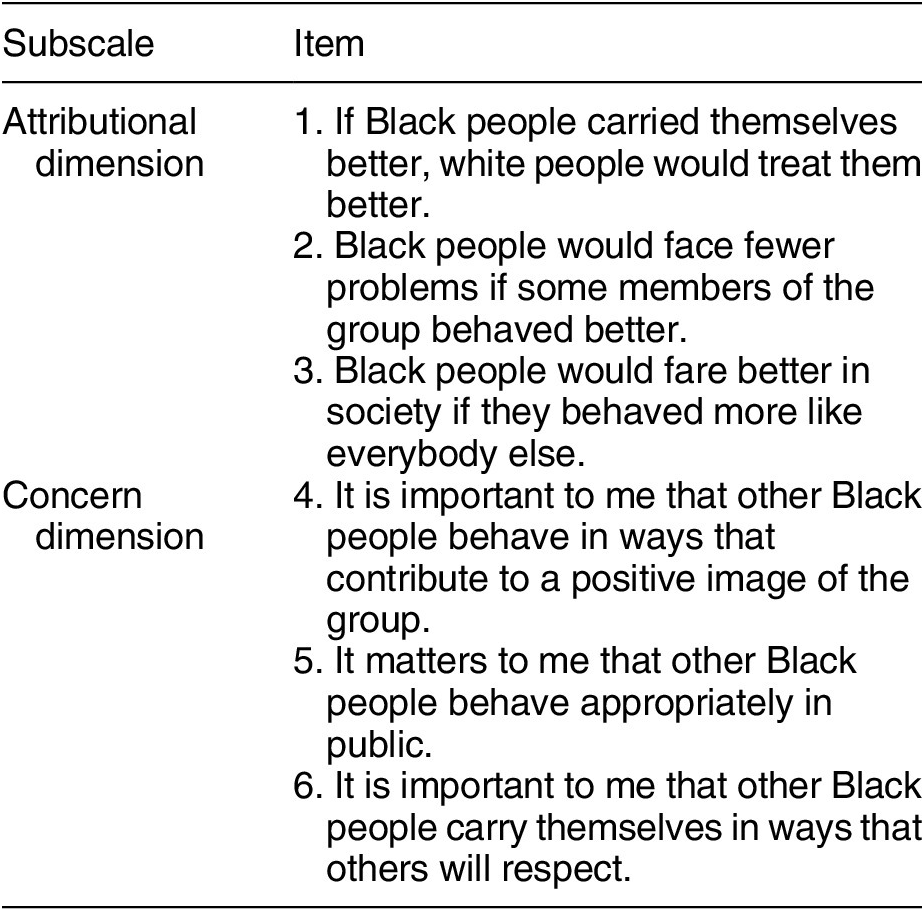

Consistent with theoretical expectations, we should observe that respectability corresponds with reactions to negatively stereotyped behavior. More specifically, respondents who score high on the RPS should be more bothered by the behavior, think it more important that individuals change their behavior, and find it more appropriate that someone says something to the individuals about their behavior. To examine the relationship between respectability and these outcomes, I run OLS regressions that include, alongside the RPS, a measure of linked fate, identity importance, age, education, income, and gender. All variables are recoded 0–1.Footnote 23

Findings

As expected, the Respectability Politics Scale is a powerful predictor of reactions to the three scenarios. In response to each scenario, we find that higher scores on the RPS correspond with being more bothered by the negatively stereotyped behavior (p < 0.001). Those who embrace respectability are also more likely to say that it is important for those committing the offense to change their behavior (p < 0.001). They are also more likely to support someone saying something about their behavior (p < 0.001). Complete results of the analyses are displayed in Figure 4. Importantly, this relationship holds even after accounting for the importance of individuals’ racial identification and their sense of linked fate with other Black Americans.

Figure 4. Respectability and Reactions to Real-World Scenarios

Note: 2019 TurkPrime data; standardized regression coefficients and 95% confidence intervals plotted from multivariate OLS model. For the three outcome measures, higher values indicate that respondents have a more negative reaction to the behavior. All variables recoded 0–1. Corresponding regression tables are included in online Appendix H.

Interestingly, in several cases, we also observe that Black respondents who say being Black is more important to their identity respond more negatively to “bad” behavior from in-group members. Though this finding warrants further investigation, it is consistent with work on stigmatized identities that suggests that identification with a domain (or identity) makes individuals more susceptible to identity threats (Steele and Aronson Reference Steele and Aronson1995). In line with existing work on stereotype threat in social psychology, this finding may indicate that Black Americans who identify strongly with their racial group react more negatively to in-group behavior that threatens their racial identity. If such a result emerges in future research, it adds complexity to our thinking about identity as it relates to respectability and in-group policing. Perhaps counterintuitively, those most interested in policing and punishing the behavior of in-group members may not be those detached from the racial group but instead may be those who see their racial identity as central to their sense of self.

Discussion and Conclusion

Though race-neutral on its face, the death penalty disproportionately kills Black Americans (Ogletree Reference Ogletree2002). Likewise, Black Americans bear the burden of strict enforcement of social welfare policies that attempt, through paternalistic and often discriminatory means, to police and discipline the behavior of the poor (Hancock Reference Hancock2004; Soss, Fording, and Schram Reference Soss, Fording and Schram2011). Thus, understanding how Americans come to their attitudes about these punitive social policies represents an important site of inquiry for social scientists, policy makers, and activists. To date, however, scholars seeking to make sense of attitudes that maintain racialized systems of social control have focused primarily on the attitudes of those outside the target group. In the rare cases when scholars have attended to the perspectives of those who belong to the target group, the focus has often been on instances of solidarity and unity, not diversity. As a result, our understanding of the broad workings of identity in American politics and its role in shaping Americans’ punitive attitudes remains incomplete.

In this article, I have sought to further nuance our understanding of the maintenance of America’s punitive social system by taking seriously the vast diversity that exists in Black public opinion. By providing a social psychological framework that connects the politics of respectability to Black Americans’ punitive attitudes, I have endeavored to demonstrate the myriad ways that identity matters for members of stigmatized groups. I have also developed the first valid measure of respectability and have presented the first empirically supported profile of those who embrace this worldview. In doing so, I highlight the importance of thinking more rigorously about self-conscious emotions like shame and embarrassment and their role in motivating individuals to police the behavior of in-group members. Importantly, this work is also the first to show the role that respectability plays—above and beyond existing measures—in explaining variation in Black attitudes toward a range of punitive policies that disproportionately affect in-group members. From support for sagging pants ordinances to beliefs about the justifiability of police shootings, respectability appears to matter a great deal in shaping the politics of Black Americans.

While acknowledging the contributions of this work, future research should do more to consider the role of context and threat in theories of respectability. Do we find, for example, that concerns about respectability increase in the presence of some more powerful out-group? Similarly, do we observe heightened levels of respectability in contexts where individuals feel more concerned about the group’s status or in contexts in which perceptions of collective costs are also heightened? And to what extent do societal shifts in perceptions of discrimination alter individuals’ embrace of respectability? For example, one may reasonably expect that social movements, like the Black Lives Matter Movement, that highlight structural explanations of racial inequality may disrupt foundational elements of respectability politics, including a belief that individual behavior drives group-based inequality. It is worth noting, however, that the data on which the current manuscript relies were collected years after activists began highlighting disparities in the criminal justice system in a movement that is noteworthy, in part, because of its seeming rejection of respectability politics (Kerrison, Cobbina, and Bender Reference Kerrison, Cobbina and Bender2018). Nevertheless, it remains an open question as to whether and, if so, to what extent respectability ebbs and flows given changes in the social context, both at the micro and macro levels. Moreover, an interesting and promising site for future research may focus, for example, on what one may call the politics of disrespectability or the purposeful rejection of respectability politics.Footnote 24

At its core, respectability politics implicates questions of intersectionality and focuses our attention on how group members are differentially marginalized in society. In developing the theoretical and empirical components of the current project, I have endeavored to engage seriously with the rich literature on intersectionality from across academic disciplines. Still, more should be done in future work to interrogate how deeper considerations of intersectionality further complicate the arguments I advance in these pages. For example, how do we fashion an empirical and theoretical account that appreciates likely differences in group members’ responses to collective threats that emerge from those who exist at different, intersecting nodes of marginalization? Moreover, how should we think about the policing of negatively stereotyped behavior that implicates multiple identities? How should we think about policing deviance, per se, versus the policing of deviant behavior that more directly implicates the group’s racial identity? One of the challenges facing scholars who work on concepts that are part of common parlance is that technical terms can take on lives of their own. In the case of respectability, the term is often used to refer to any instance of in-group policing or sanctioning among Black Americans. Here, I have sought to be more careful and precise in my use of the term. However, I welcome future efforts that interrogate the conceptual choices I have made, especially as they help clarify the concept’s scope and influence.

Other, broader questions remain regarding the emergence and maintenance of punitive attitudes among members of stigmatized groups. Scholars should endeavor to understand, for example, why members of stigmatized groups often report higher levels of authoritarianism than do their nonstigmatized counterparts (Pérez and Hetherington Reference Pérez and Hetherington2014). In doing so, future research should pay careful attention to experiences of stigma as potential determinants of individuals’ broader beliefs about conformity, order, and punitiveness. That is, scholars should consider the extent to which stigmatized groups come to their attitudes about conformity and order through more instrumental means than do their nonstigmatized counterparts (see, e.g., Taylor, Hamvas, and Paris Reference Taylor, Hamvas and Paris2011). In taking up these questions, scholars should look beyond existing measures, such as linked fate, to develop more precise measures of the kinds of concerns members of stigmatized groups engage, such as concerns regarding collective costs. As we observe in the current study, linked fate appears to be a deficient proxy for perceptions of collective costs among Black Americans, which further highlights the importance of moving away from an overreliance on the measure of linked fate in charting the contours of Black politics.

The focus of this study has been Black people and Black people’s politics. At its core, however, the project provides a portable theoretical framework for scholars interested in understanding similar processes that manifest among members of other stigmatized social groups. For example, the theoretical arguments put forth can be used to help understand variation in Latinx attitudes toward policies related to immigration. To what extent do group members support restrictive immigration policies as a means of distancing themselves from or punishing those who threaten the image or status of those already living in the United States? Likewise, do we observe similar processes among Muslim Americans who may be motivated to support harsh punishment for group members whose actions threaten the group’s image and the group’s already-precarious place in American society (e.g., see Lajevardi Reference Lajevardi2020)? We may wonder, still, how these processes manifest for a variety of social groups, including women and members of the LGBTQ community who may support policies that are seemingly bad for other members of the group. Insofar as groups exist along social hierarchies in various contexts, we should observe similar dynamics at play. And, perhaps provocatively, there may even be contexts in which we observe these processes among members of dominant groups. For example, do we observe that some white Americans are motivated to police and punish racist behavior from in-group members, given the negative stereotypes that attach to whiteness and white Americans’ perceived vulnerability when issues of race are brought to the fore (e.g., Jefferson and Takahashi Reference Jefferson and Takahashi2021; Takahashi and Jefferson Reference Takahashi and Jefferson2021)? These are important questions that future research should carefully engage.

For the current project, the main implication is this: those interested in understanding the maintenance of punitive social systems must seriously consider the diversity of views among the target group. They must also endeavor to understand the social and psychological factors that explain that diversity. That has been the goal of this work, which develops a social psychological framework that connects respectability to Black Americans’ punitive attitudes. I hope future scholarship builds on these insights to add necessary nuance to our understanding of identity and its place in our politics, especially as it relates to questions of justice for marginalized groups. As scholars set out to do this work, I encourage renewed attention to the diversity of perspectives that exist among members of stigmatized social groups. By attending to these perspectives, we do more than improve our theoretical understanding of the workings of identity. We recenter in our conversations about justice those we too often treat as mere objects of some other group’s affection or disdain. Appreciating the full humanity of those we study means taking them and their politics seriously. I have sought to do that here and hope this work inspires others to do the same.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055422001289.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research documentation and data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the American Political Science Review Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/IOAMVW.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am indebted to far too many people to name for their helpful feedback on this project. Special thanks, however, to my dissertation committee at the University of Michigan: Vince Hutchings, Ted Brader, Allison Earl, Don Kinder, and Rob Mickey. I am also grateful to Neil Lewis whose conversations with me early in graduate school inspired me to consider how notions of stigma and stereotype threat might apply to the study of Black politics. Thanks to Cathy Cohen for her pioneering work that has greatly influenced the work contained in these pages. Thanks also to those at various institutions who helped me workshop the project when I was on the academic job market. Thanks to Kory Gaines, Kobe Hopkins, Sophia Helfand, and Alan Yan for their brilliant research assistance at various stages of the project. And finally, thank you to the folks I grew up around in rural South Carolina who gave me a better education about the nature of Black politics than any course I could imagine taking. An earlier version of the project was presented at the American Political Science Association, the Midwest Political Science Association, and the Princeton Policing Mini-conference, and the National Conference of Black Political Scientists, among other venues. All errors that remain are my own.

FUNDING STATEMENT

This research was funded by Stanford University. Earlier versions of the manuscript included data funded by the generous support of the Garth Taylor Fellowship in Public Opinion at the University of Michigan.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The author declares no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.

ETHICAL STANDARDS

The author declares the human subjects research in this article was reviewed and approved by Stanford University’s Institutional Review Board and certificate number is provided in the text. The author affirms that this article adheres to the APSA’s Principles and Guidance on Human Subject Research.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.