The examination as a tool for selecting public servants has a long history. Today, virtually every country around the world has adopted a variant of this model in principle. The central virtue of the examination lies in its capacity to identify qualified applicants while also ensuring that the means of their selection is divorced from the short-sighted electoral interests of politicians. Over and again, scholars have found that countries in which civil servants are recruited according to “merit” report stronger economic performance and boast superior service delivery (Evans and Rauch Reference Evans and Rauch1999; Pepinsky, Pierskalla, and Sacks Reference Pepinsky, Pierskalla and Sacks2017; Rauch and Evans Reference Rauch and Evans2000). Concerned policy makers and international development organizations have taken notice. The World Bank in recent years, for instance, has spent US$50 billion supporting civil service reform initiatives, an umbrella term that includes promoting the use of examinations in recruitment decisions (cited in Cruz and Keefer Reference Cruz and Keefer2015, 1943).

In this paper, I present an argument and evidence challenging this absolute normative preference for the examination as the singular tool for civil service recruitment. I argue that the outcomes of civil service examinations may prompt unexpected attitudinal shifts on the part of winners and losers—particularly when successful applicants disproportionately hail from specific ethnic, racial, or religious groups. Decomposing this argument, I first hypothesize that unsuccessful applicants might come to harbor significant resentments as they grapple with the upsetting reality of their own failure. I also hypothesize that, to the extent that success results in government employment, the experience of passing the examination might result in countervailing attitudinal changes, as newly minted public servants adopt attitudes consistent with a view that success was theirs alone rather than partially attributable to, say, systemic inequities or institutional shortcomings.

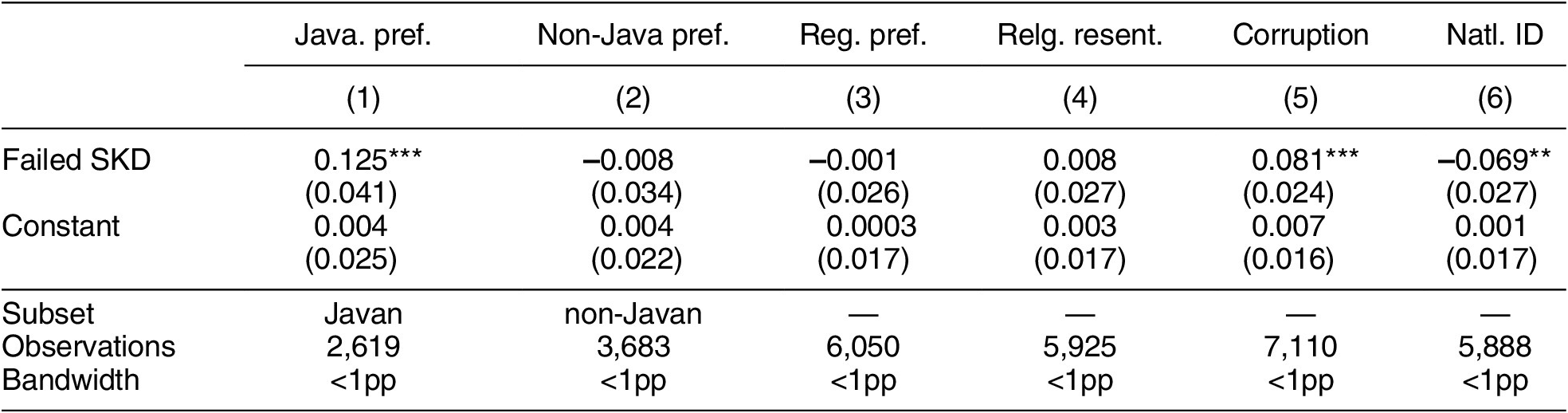

To evaluate these arguments, I employ a regression discontinuity framework that leverages civil servant examination scores in Indonesia to identify variation in the experience of failure or success. Importantly, this approach is dogged by the inferential concern that differences across these groups could be attributed to either the experience of failure or to the experience of success (and by extension the experience of government service). To sort out these competing possibilities, this paper leverages Indonesia’s sequential and nested system of civil service examinations in which applicants must first take a basic competence examination (Seleksi Kompetensi Dasar, SKD) and, conditional on passing, may be invited to take a specialist competence examination (Seleksi Kompetensi Bidang, SKB). To isolate the chief estimand of interest—the effect of failure—I compare the attitudes of losers and winners on the basic competence examination. But I also subset the sample to those who ultimately did not receive a government job. My preferred interpretation is that any differences in attitudes across these groups is attributable to the sting of failure alone, as it seems unlikely that individuals who pass the screening examination but fail at a later stage would feel any countervailing sense of inflated self-worth.

The structure of Indonesia’s system of bureaucratic recruitment also offers the opportunity to examine the effect of being selected for public service. Here, I focus on individuals who were invited to sit for the specialist competence examination—the final stage of the recruitment process, after which applicants were ranked in descending fashion and deterministically selected for vacancies. To capture the effect of public service, I compare the attitudes of those who were narrowly selected to join the civil service with the attitudes of those that were narrowly passed over. To support the interpretation that these differences are attributable to government service—rather than an artifice of the aforementioned effect of failure on the part of the counterfactual group—I conduct a test in which I compare the attitudes of those who accepted the offer with the attitudes of those who turned it down.

To collect the relevant outcome data, I partnered with the Indonesian civil service agency. We solicited survey responses from all 3,636,262 individuals who applied for public sector jobs during the 2018–2019 cycle, receiving responses from a total of 204,989 individuals. The survey was fielded approximately 16 months after examination outcomes were known to applicants and approximately 4 months after the end of a one-year probationary period for applicants selected to become civil servants. The survey probed five genres of attitudinal outcomes: (1) preferentialism for residents of the most populous island (Java), (2) preferentialism for district insiders, (3) resentment of religious outsiders, (4) support for the inclusivist Indonesian national identity, and (5) belief in the legitimacy of the recruitment process. Survey responses were then linked to the database of examination scores, enabling a comparison of attitudes across successful and unsuccessful candidates. To overcome concerns of omitted variable bias, for each threshold, I restrict the main analysis to applicants whose final scores were less than a single percentage point from an alternative outcome—subsets of observations in which I assert that the outcome of success or failure for any given observation was as good as random.

To preview the results, first, I find that failure on the basic competence examination leads to an uptick in support for Javan preferentialism among Javans, a decrease in support for the Indonesian national identity, and an increase in a belief that the recruitment process was corrupt—findings that suggest that the effect of failure is causally significant. To bolster my preferred interpretation, I demonstrate that these results persist even after I restrict the sample to individuals who ultimately did not receive a job. Second, turning next to the effect of public service and looking at the same outcomes, I show that applicants from Java who narrowly received a job offer, when compared with residents of Java who narrowly did not receive a job offer, are less likely to support government preferentialism for Javans. Applicants who narrowly received a job offer are also less likely to protest the arrival of—and less likely to oppose policies supporting—migrants from outside the region. Narrowly selected applicants are less likely to reflect negatively on their national identity. And finally, fourth, applicants who narrowly received a job offer are systematically less likely to view the recruitment process as having been corrupt.

The two dominant contributions of this paper relate to establishing an effect of examination failure. First, for scholars focused on the bureaucracy, it foregrounds an overlooked trade-off in the decision to use examinations to recruit civil servants: this system evidently creates significant attitudinal rifts between winners and losers, which, at scale, could threaten a sense of social cohesion. Particularly in cases where group-based inequality is extremely high, as in much of Asia and Africa, this argument provides a partial explanation for the puzzling resistance of certain countries to adopting a genuine commitment to the merit-based recruitment of civil servants: policy makers in these cases might simply deem the costs of such a policy too high in terms of potential for conflict.

Second, for scholars interested in the origins of ethnic strife and conflict, this paper represents an effort to bridge institutional and behavioral approaches. Recent scholarship proposing institutional explanations have advanced variants of the argument that entrepreneurial politicians are to blame for ethnic strife, as they gin up divisions for electoral and political gains (McCauley Reference McCauley2014; Wilkinson Reference Wilkinson2004). These accounts are compelling but fail to explain why politicians’ divisive appeals are persuasive in the first place. The theory and evidence presented in this paper offer a partial answer to this question by demonstrating how the distributional consequences of prior institutions can create the behavioral foundations of latent grievance upon which politicians can later seize.

Theorizing The Effect of Civil Service Examination Outcomes

The Effect of Examination Failure

Failure is an inescapable consequence of examinations. But the nature of failure on a high-stakes examination may be a uniquely devastating insult: to be examined and judged to possess insufficient “merit” is an upsetting reality for many applicants to face. A cross-disciplinary literature in education and psychology has identified the ways in which high-stakes examinations heighten test takers’ anxiety and, in the event of failure, lead to feelings of shame and humiliation (Diener and Dweck Reference Diener and Dweck1978; Elliott and Dweck Reference Elliott and Dweck1988; Kearns Reference Kearns2011). Leveraging a natural experiment in which hundreds of high school students were erroneously told that they failed the Minnesota Basic Standards Test, for instance, Cornell, Krosnick, and Chang (Reference Cornell, Krosnick and Chang2006) document that over 80% of the wrongly failed students reported that they felt “depressed or embarrassed” and 4% of these students ultimately dropped out of school.

It seems likely that—in addition to feelings of shame and humiliation—unsuccessful test takers will search for exculpatory justifications. People want to see themselves as high quality, and when they receive negative evaluations, they may develop new beliefs about the process that protect that view (Little Reference Little2019). This possibility draws from “attribution theory,” a body of research in psychology that seeks to explain how individuals understand the causes of certain human-influenced events.Footnote 1 Particularly in the context of examination outcomes, attribution theory has been applied to investigate how failed students’ evaluations of their own performance (e.g., as a consequence of lack of effort or due to lack of inherent ability) might influence later behavior and attitudes (Dweck Reference Dweck2008; Graham Reference Graham1991). One particularly relevant outgrowth of the attribution theory literature is a strand of research focusing on the influence of “self-serving biases” in the attribution of success and failure on assessments (Miller and Ross Reference Miller and Ross1975; Sicoly and Ross Reference Sicoly and Ross1977). Research has found that individuals are more likely to take responsibility when they succeed on examinations, whereas they are less likely to take responsibility when they fail. It seems likely, then, that unsuccessful test takers will be more likely to search for explanations that absolve their own role in a failed outcome.

The theorized effect of examination failure extends this literature in several respects. For one, I focus on civil service examinations as opposed to academic assessments. As the outcomes of these tests confer considerable status and employment, it might be that any frustrations stemming from failure are comparatively larger than those seen in other contexts. But particularly crucial for the present discussion is the observation that, as opposed to academic contexts, frustrations over recruitment into government service may have unintended consequences for applicants’ attitudes toward the state itself. Failed applicants—as they seek to attribute a cause for their own shortcomings—may adopt new attitudes toward specifically political institutions thought to have played a role in their failure. For instance, the often-cited justification for introducing meritocratic examinations as the mechanism for public sector recruitment is to manage public frustration over the role of patronage and corruption in the allocation of government jobs. Yet, it may be that failure on these examinations motivates forms of frustration that lead applicants to believe the process to have been unfair anyways, thus entrenching the political attitudes that the introduction of the merit system sought to remedy.

In general, this expectation draws on several related literatures spanning political science, education, and psychology. In the political science literature, the hypothesized effect of failure maps onto an older literature in comparative politics concerning “frustrated expectations.” Here, Gurr (Reference Gurr1970) famously argued that “men rebel” when their personal ambitions are systematically foreclosed. In a more recent addition, Nielsen (Reference Nielsen2017) traces how Islamic scholars turn to Jihadism in the event that they find their ascent through traditional scholarly communities blocked—an experience described as “thwarted ambition.” More immediately relevant to the context of civil service recruitment, Elman (Reference Elman2013, 169) describes the climate in imperial China during the Qing dynasty in which “the search for examination success created a climate of rising expectations among low-level [elites] who dreamed of examination glory who sometimes rebelled when their hopes were dashed.”

To summarize, I expect that failure on the civil service examination will affect several different genres of outcomes. First, it may be that failed applicants will be more likely than successful applicants to allege corruption in the recruitment process—for instance, as they search for exculpatory explanations of their failure. Second, and particularly in contexts with high group-based inequality, failing an examination may motivate out-group resentment and in-group preferentialism as unsuccessful test takers attribute the outcome to systemic inequalities. Finally, third, failing may prompt individuals to reflect negatively on the national identity writ large, as it represents the symbolic core of the institution from which they have been denied employment.

The Effect of Public Service

The purpose of civil service examinations is to impartially select competent candidates and confer upon them public sector employment. Proponents often assert that this system of recruiting civil servants is designed to unlock gains in the quality of service delivery and, in turn, aggregate growth (Evans and Rauch Reference Evans and Rauch1999; Johnson Reference Johnson1982; Pepinsky, Pierskalla, and Sacks Reference Pepinsky, Pierskalla and Sacks2017; Rauch and Evans Reference Rauch and Evans2000; Weber Reference Weber1978). But the experience of being offered—and accepting—a job in the public sector may have independent effects on successful candidates’ attitudes. In other words, in addition to the hypothesized attitudinal influence of the examination itself, outlined above, I also theorize that the experience of public service may have important and countervailing effects. For one, drawing again on attribution theory, and in particular the work of Sicoly and Ross (Reference Sicoly and Ross1977), individuals who were successful in the selection process often have an incentive believe that success was theirs alone. This outlook may lead successful applicants to adopt attitudes consistent with this view. For instance, successful applicants may assert that the process was fair and free from corruption or that systemic inequalities across group lines were not operative factors in their success.

Consistent with this, but drawing instead on system-justification theory (e.g., Jost Reference Jost2019), and particularly in the context of civil service examinations, successful applicants may feel the need to offer legitimating statements the uphold the outcome that resulted in their employment. So, for instance, they may assert the fairness of the process carried out by their now-current employer. Relatedly, it may be that individuals who are employed by the state itself will be more likely to identify with the national identity, which is often understood as the symbolic core of the state itself.

Finally, as a consequence of gaining public sector employment, it may be that successful applicants are more likely to interact with fellow citizens from a range of backgrounds, which may induce warmer feelings toward out-groups, chip away at tribalism, and bolster a sense of national identification. This is of course particular to the context of civil service examinations rather than high-stakes examinations writ large. Nonetheless, a large literature has investigated variants of this argument—known as the contact hypothesis—and has demonstrated that the experience of interacting with individuals from out-groups can lead to meaningful ideational changes (Allport Reference Allport1954; Paluck and Green Reference Paluck and Green2009; Weiss Reference Weiss2021). The hypothesized direction of this effect is indeterminate, however: a recent meta-analysis by Paluck, Green, and Green (Reference Paluck, Green and Green2019) finds mixed results in general, particularly among adults for whom prejudicial attitudes may be especially rooted. In a field experiment, Mousa (Reference Mousa2020) finds that the salutary effects of contact are bounded to the social setting in which they take place. In another, Hässler et al. (Reference Hässler, Ullrich, Bernardino, Shnabel, Van Laar, Valdenegro and Sebben2020) show that the intergroup contact is positively correlated with support for social change among members of advantaged groups but negatively correlated for members of disadvantaged groups.

However, the experience of intergroup contact in the context of public service may be uniquely influential. For one, as the civil service draws on applicants from all backgrounds, it may be that selected applicants encounter a higher level of workplace diversity than they would otherwise. For instance, recent work by Andersson and Dehdari (Reference Andersson and Dehdari2021) has shown that voting precincts with greater workplace diversity in Sweden report lower tallies for anti-immigrant parties. But the public sector also asks its employees to serve an unusually broad swath of the public, which may induce greater amity toward certain groups and institutions. Moreover, the diversity encountered in the public sector—as when citizens petition services from bureaucrats of different ethnicities—may inspire greater amity than analogous situations in, say, commercial workplaces, as it occurs against the backdrop of a shared project of nation- and state-building. Looking at the effect of public service on the attitudes of Americans selected to be public school teachers, for instance, Mo and Conn (Reference Mo and Conn2018, 722), find that “participation [in public service] lessens prejudice toward disadvantaged populations and increases amity toward these groups.”

Context: Why Study Civil Service Examinations in Indonesia?

Indonesia is an apt case to evaluate the theory advanced in this paper for two reasons. The first reason concerns recent reforms in the recruitment procedure. In many lower- and middle-income countries, the results of civil service examinations are routinely manipulated (e.g., Grindle Reference Grindle2012). Even in postwar Italy, a comparatively industrialized case, Golden (Reference Golden2003) estimates that, between 1973 and 1990, more than half of civil servants were recruited in such a fashion. Until recently, Indonesia was no different. Applicants to the civil service in Indonesia sat for paper-based examinations in large stadiums with thousands of other applicants. Complaints of manipulated scores were widespread. One study found that applicants often paid administrators to boost their scores (Kristiansen and Ramli Reference Kristiansen and Ramli2006).

However, Indonesia recently implemented a new computer-assisted test (CAT). Rolled out on a national scale in 2018–2019, the CAT is centrally implemented and mechanistically graded and is widely believed to have effectively rooted out foul play in the recruitment process (Beschel et al. Reference Beschel, Cameron, Kunicova and Myers2018).Footnote 2 The newly implemented system contained five phases:

-

1. Job search: Applicants search for job openings on the online database.Footnote 3 The location, title, requirements, and number of vacancies for positions are listed in a searchable database. During 2018–2019, there were 180,623 vacancies to which applicants applied.

-

2. Administrative selection: Applicants apply for a single position by submitting their documents for a review of completeness (e.g., transcript, diploma, birth certificate, etc.) through an online portal. Successful applicants were invited to participate in the next phase—the “basic competence examination.”

-

3. Basic competence examination (SKD): The basic competence examination takes 90 minutes and involves three sections: (1) a general intelligence test, (2) a personality test, and (3) a nationality test. The total components add up to a maximum score of 500. A nationwide threshold was set at 255. Applicants were immediately notified of their score upon completion of the test. Applicants above the threshold were then ranked in descending fashion, with the top three scoring applicants invited to continue to the fourth phase—the “specialist competence examination.”Footnote 4

-

4. Specialist competence examination (SKB): The specialist competence examination measures applicants’ preparedness for the specific tasks of the position to which they are applying. For 100% of district and provincial positions, as well as the vast majority (although not all) of central government positions, this test is also carried out as a computer-assisted system.Footnote 5 Applicants were not notified of their score on this examination.Footnote 6

-

5. Score integration and selection: After the specialist competence examination, the scores on the two tests are integrated—the basic competence examination weighted at 40% and the specialist test weighted at 60%. Applicants are then ranked in descending order, with the top scoring candidate selected for the vacant position.

Initially rolled out in 2008 for internal recruitment of candidates at the civil service agency, some applicants continued to complain that the scoring of the examination under the CAT system was still opaque. The numbers could have been manipulated by a computer administrator after the fact. Further reforms introduced in some locations have mitigated these concerns. During the 2018–2019 cycle, on the day of the test, applicants’ families were assembled in an adjacent room while the results were live-streamed on a scoreboard with applicants’ scores (and thus relative positions) updated as they answer each individual question correctly or incorrectly. Where introduced, this gladiatorial approach to civil servant selection appears to have been effective in curbing concerns over score falsification.

A second reason to focus on Indonesia is the scale of group-based inequality. The world’s fourth most populous country, Indonesia harbors at least three important axes of group-based privilege that serve as the engine of uneven rates of representation in bureaucratic institutions. The organizing axis of privilege in Indonesia is interisland, with the historically dominant residents of Java controlling a disproportionate stake of industry and government. A second important cleavage is a localized form of nativism: many Indonesians seek out employment in districts beyond their own, a dynamic that heightens the salience of slight differences as migrants and natives of the same island compete for scarce opportunities, often in regional capitals. A final third cleavage is religious. By law, all Indonesians must profess a religion, with 88% adhering to Islam and the remaining 12% belonging to minorities of Christians, Buddhists, and Hindus. Historically, religion has been a major source of conflict in Indonesia, with members of minority religious sects having been occasionally targeted in pogroms and are often the object of stigma and abuse.

In general, these cleavages dovetail with economic advantages. For instance, according to the 2014 Indonesian Family Life Survey (IFLS), district outsiders make 61.2% more than their locally native counterparts. Similarly, Indonesians who reside on Java earn 30.8% more than do their peers on outer islands. According to the same data, and despite representing an overwhelming 88% of the population, Muslim Indonesians earn 2.8% less than non-Muslims do. However, it is worth underscoring that this difference is slight and Muslims’ demographic advantage may carry intangible benefits for their examination outcomes vis-à-vis non-Muslims.Footnote 7 Taking these ingredients together, privileged groups—residents of Java, district outsiders, and Muslims—have generally outstripped their counterparts on civil service examinations. Looking specifically at the score on the basic competence examination, on average, applicants from districts on Java score 27 points higher than do applicants from outer islands. Similarly, applicants who apply for positions in districts in which they do not reside score 15 points higher than do local natives. Finally, Muslim applicants score seven points higher than do their non-Muslim peers.

There is some evidence that these dynamics have introduced strategic considerations in the recruitment process, as applicants from privileged groups seek out employment in places where they perceive the competition to be weaker and chances of success to be higher. For instance, 44% of applicants for civil service jobs seek out employment in jurisdictions different from their place of residence. Tenure as a civil servant takes effect after one year. And tenured civil servants can request a transfer after three years in their initial posting. Predictably, local applicants are often hostile to this strategy and the outsiders that it brings. Aspiring public servants from marginalized communities and districts—such as those in Papua and Maluku—have often lodged protests to demand either restrictions on outsiders obtaining government jobs or quotas for local applicants (known as putra/putri daerah). This dynamic is a crucial engine on the part of both hypothesized effects. In the context of the effect of failure, it seems likely that these dynamics will spur frustration on the part of applicants who fail the civil service examination and that this frustration may in turn motivate a suite of other attitudinal shifts. On the part of successful test takers, in particular those who accept the offer of employment and who venture to new districts, it seems likely that this experience will motivate the “perspective taking” that could shift attitudes, as well.

Research Design

Estimating the “effect” of success or failure on the civil service examination is dogged by serious inferential concerns. The first inferential issue relates to the compound nature of the intervention: in the absence of a pure control, observed attitudinal differences across winners and losers could reasonably be interpreted as either the the effect of failing or the effect of succeeding and going on to become a civil servant. To be clear, my preferred interpretation is that both mechanisms are at work. To sort out the comparative magnitude of these twinned mechanisms, I leverage different thresholds within the civil service recruitment procedure (see Figure 1). The first threshold involves applicants’ scores on the basic competence examination, a test that determines whether a candidate continues to the next phase of recruitment. Importantly, success on this test does not result in employment, which, I argue, enables an attribution of the attitudinal differences across winners and losers to the simple fact of failure or success. Skeptics of this approach might be concerned that some proportion of applicants who pass the basic competence examination go on to become civil servants, thereby undermining an attempt to narrowly isolate the effect of failure. Although the scale of this bias is likely small thanks to the small share of matriculants, I also conduct an analysis restricted to those applicants who ultimately did not receive a job, thereby decoupling any so-called public service effect.

Figure 1. CONSORT Flow Diagram

Isolating the effect of government service is more straightforward. Here, I focus on applicants who had advanced to the final stage of the recruitment process—those who had taken both the basic competence examination and specialist competence examination. In addition to passing the absolute score threshold on the screening examination, applicants must also filter through the “rule of three,” which stipulates that only the top three scoring candidates on the basic competence examination for any given vacancy are invited to take the specialist competence examination. After this stage, recall that the two scores are integrated as a weighted average and applicants are ranked in descending fashion within each vacancy. The proposed analysis compares the attitudes of applicants who were offered a position with those who were not. To bolster the interpretation that these differences are narrowly attributable to government service rather than an additional manifestation of the hypothesized effect of failure, I conduct a test in which I compare the attitudes of those who accepted the offer with the attitudes of those who turned it down. Again, it is worth underscoring that this approach introduces certain biases into the estimates, as the decision to accept an offer of employment is not randomly assigned.

The second pressing inferential difficulty is confounding: it might be that, for both thresholds, people who fail are systematically different from people who succeed on a host of observed and unobserved characteristics. And it might be that it is these characteristics that drive observed differences in the outcomes. To address this issue, at both thresholds, I adopt a regression discontinuity design to estimate the effect of losing (passing) at the different thresholds on the outcomes of interest. The identifying assumption of this approach is that, at both thresholds and within a narrow bandwidth, whether or not an applicant passes or fails is as good as random. In the Supplementary Materials (SM), I conduct a series of tests bolstering the validity of this assumption (see Section B).Footnote 8 Note, importantly, that the forcing variable is different in the analyses. The first forcing variable is absolute: it is an applicant’s percentage-point distance to the score threshold (51%).Footnote 9 The second forcing variable is relative, as in the case of commonly used close-election regression discontinuity designs: it is an applicant’s percentage-point distance to an alternative disposition.

To collect the relevant outcome data, working with the Indonesian civil service agency, we sent emails to all 3,636,262 applicants from the 2018–2019 cycle, soliciting their participation in an online survey. We had initially planned to send the survey solicitations in March 2020, approximately 12 months after the examination scores were known to applicants and one month after the end of a one-year probationary period for applicants selected to be civil servants (see Figure 2). This plan was aborted due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Instead, we sent the survey solicitations via email in July 2020, 16 months after the basic competence examination.Footnote 10 As this exceeds the typical time frame over which follow-up surveys are conducted after an informational intervention (i.e., 1–8 weeks; see Haaland, Roth, and Wohlfart Reference Haaland, Roth and ForthcomingForthcoming), I argue that any observed effects ought to be attributable to durable attitudinal shifts rather than, say, transitory frustrations. In the end, we obtained responses from a total of 204,989 individuals, for a response rate of 5.2%.Footnote 11 From the perspective of nonresponse bias, the main estimation sample appears similar to the underlying population (see SM Section B), with the exception of some age brackets and respondent location.Footnote 12 Each email contained a unique link such that the survey responses could be linked to an individuals’ civil service examination score. Finally, we did not incentivize participation in the survey.

Figure 2. Indonesian Civil Servant Selection Timeline, 2018–2019

For the dependent variables, I construct five “families” of outcomes—each of which contain two to five questions.Footnote 13 These questions are drawn from work by Soderborg and Muhtadi (Reference Soderborg and Muhtadi2021) in which the authors develop and validate a battery of survey measures designed to gauge common axes of resentment in Indonesia.Footnote 14 I include the paraphrased text of these questions, as well as the range of potential responses, in Table 1. First, “Javan preferentialism” (Javan Pref.) gauges respondents’ degree of support for policies that prioritize the interest of residents of Java. Second, “regional preferentialism” (Reg. Pref.) gauges respondents’ support for policies that prioritize regional natives. Third, “religious resentment” (Relg. resent.) gauges respondents’ resentment toward generalized religious out-groups. Fourth, “national identification” (Natl. ID) comes from two questions that measure the applicants’ identification with an ethnically inclusive formulation of the Indonesian national identity. Finally, fifth, “perceptions of corruption” (Corruption) comprises five questions measuring applicants’ perceptions of corruption in the recruitment process.Footnote 15 To simplify interpretation, I create indices following the procedure outlined by Kling, Liebman, and Katz (Reference Kling, Liebman and Katz2007) such that outcomes are measured in terms of “control-group” standard deviations.Footnote 16

Table 1. Survey Questions, Outcomes, and Families

For the estimation, I conduct a simple difference-in-means analysis implemented using ordinary least squares (OLS). Specifically, for the two main analyses, I regress the outcome variables on an indicator variable that captures whether an applicant failed (or passed) at the two different thresholds. Again, I restrict the analysis to observations in which applicants’ scores were less than a single percentage point from an alternative disposition.

Results

What Is the Effect of Examination Failure?

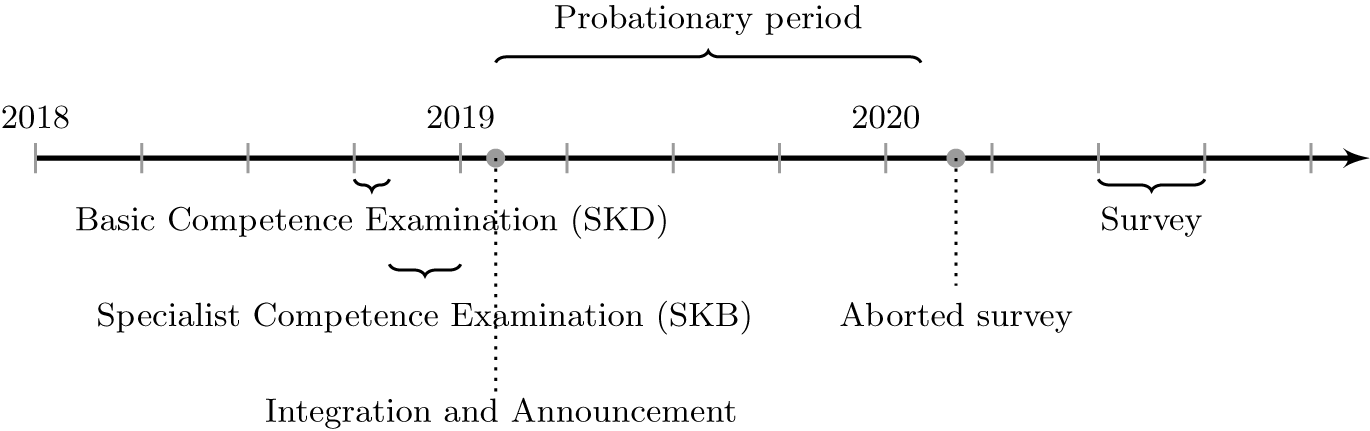

To start, how do individuals who narrowly failed the basic competence examination compare with those who narrowly passed? I investigate this question by examining the five indices discussed above—support for Javan preferentialism, support for regional preferentialism, religious resentment, perceptions of corruption, and levels of national identification. I present the results in Table 2. In the first column, I look at an indexed battery of questions gauging support for government preferentialism for Java—Indonesia’s most populous and, by most accounts, its most privileged island. I ask respondents whether or not they support government interventions designed to provide preferentialism to Java (1) generally and (2) in terms of access to resources. Per the preanalysis plan, I conduct a split-sample analysis that compares the attitudes of narrow losers with those of narrow winners on Java and off-Java.

Table 2. The Effect of Basic Competence Examination (SKD) Failure

Note: Beta coefficients from OLS regression. Standard errors were calculated using the Huber-White (HC0) correction. The outcomes measure are indexed values capturing (1) Javanese preferentialism among Javans, (2) Javanese preferentialism among non-Javans, (3) regional preferentialism, (4) religious resentment, (5) perceptions of corruption, and (6) national identification; pp = percentage point; *p < 0.10, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

Recall that I leverage variation in the experience of failure on the basic competence examination. Compared with narrow winners, narrow losers from Java are significantly more likely to support government intervention on behalf of residents of Java. Specifically, implementing the baseline specification indicates that narrow losers are 0.13 SDs more likely to be supportive of giving Java governmental “priority” and “resources” than were narrow winners—a finding that supports the relevant preregistered hypothesis. The second column presents the results for the subset of applicants who did not reside on Java. The outer islands are generally believed to be a secondary concern for government policy compared with the attention given to Java. It might thus be the case that the experience of losing on a civil service examination could prompt further frustration toward the dominance of Javans, manifested in a decrease in support for government interventions of Javan preferentialism. Yet, surprisingly, the results presented in Table 2 detect no signs that this more marginalized subset of the population is more prone to hostility toward Javan preferentialism in the event of narrowly losing, when compared with narrow winners. It might be that this null result is driven by floor effects: for instance, only 11.9% of non-Javans agree that the government should “prioritize the needs of Javans because the majority of Indonesians live there.”

A more general form of regional preferentialism might also be affected by the outcome of civil service examinations. Among applicants for positions in the local and regional civil services, 44% applied for positions outside the jurisdiction in which they currently reside. Anecdotal evidence suggests that many of these “outsider” applicants are often well-educated city dwellers who are motivated by strategic considerations.Footnote 17 It seems likely that this dynamic might heighten regionalism and regional preferentialism on the part of locals that fail the examination and believe winners to come from elsewhere. To gauge this possibility, the survey asked respondents three questions, two of which concern matters of normative preference and one of which concerns an evaluation of current government policy—but all of which concern regional preferentialism. The results are presented in column three of Table 2 and show that, in contrast to the preregistered hypothesis, narrow losers are no more supportive of regional preferentialism than are narrow winners.

Next, I investigate how the outcomes of civil service examinations affect attitudes toward religious out-groups. These questions differ in important respects from the previous two “families” of outcomes, as they do not gauge in-group preferentialism. Religion has historically been an important cleavage in Indonesian political life; thus, Indonesia’s constitutional framework strictly outlaws preferentialism on religious grounds. Questions probing either support for such policies, or perceptions of their presence would have likely been met with nonresponse or denial. Instead, I asked respondents a series of questions designed to measure a broader form of “resentment” toward religious out-groups. These questions asked respondents if they would be “upset” if members of different religions (1) built places of worship nearby, (2) were elected to local office, or (3) were hired as a bureaucrat. Column four of Table 2 presents the results. Again in contrast with the expectations registered in the preanalysis plan, I detect no evidence that narrow losers are any more likely to indicate hostility toward religious out-groups when compared with narrow winners.

Next, how do narrow losers perceive the recruitment process in terms of transparency and corruption, compared with narrow winners? The theory advanced in earlier sections predicts that losers in particular have an incentive to allege the recruitment process was corrupt in order to exculpate their shortcomings. To test this possibility, I quizzed applicants on a range of questions designed to measure respondents’ views about the extent to which certain factors (merit, connections, ethnicity) were influential in recruitment decisions. I also asked respondents the extent to which they believed the recruitment and selection process was transparent and asked respondents to choose between a binary option of “examination” and “connections” as the most important factor in recruitment decisions.

The results are presented in column five of Table 2. The baseline specification shows that narrow losers, compared with narrow winners, are 0.08 SDs more likely to believe the recruitment process was corrupt. Decomposing some of the items in the index to provide a more concrete indication of the magnitude of the effects, consider that narrow losers are 2.1 percentage points more likely to say that connections were more important than examination results in hiring decisions, a 9.1% increase over narrow winners. Moreover, and particularly relevant to the theory advanced in this paper, compared with narrow winners, narrow losers were 1.5 percentage points more likely to say that ethnicity was a factor in hiring decisions—corresponding to a 9.2% increase. Champions of the merit system often cite its transparency as one of its chief advantages; these findings are thus particularly striking because they suggest that the experience of failing on the examination may undermine perceptions of its legitimacy.

Finally, how do narrow losers compare to narrow winners in terms of support for the Indonesian national identity? Recall that the core of the Indonesian national identity is a doctrine known as Pancasila, which posits an ethnically and religiously inclusive vision. Nonetheless, all Indonesians possess multiple identities, including ethnic commitments. The survey thus asks respondents two questions. First, it probes respondents’ attitudes about the extent to which Pancasila is still “relevant,” and, second, it asks respondents whether they identify as Indonesian, their ethnicity, or a little bit of both. The results are presented in column six of Table 2 and indicate that narrow losers are significantly less likely likely to indicate support for the Indonesian national identity. Broadly, I find that narrow losers are 0.07 SDs less likely to support Indonesia’s national identity when compared with narrow winners. Specifically, and again decomposing the index for clarity, narrow losers are less likely to believe that Pancasila is still relevant by about 1.7 percentage points, corresponding to a 3% decrease over narrow winners.

My preferred interpretation of the results presented in Table 2 is that they are attributable to the experience of failure on the basic competence examination. However, in the absence of a “pure” control, observed differences around the threshold could be interpreted as either the effect of narrowly succeeding on the examination or the effect of narrowly failing the examination. To sort out this inferential difficulty, in Table 3, I restrict my sample solely to those applicants who ultimately did not receive a job—an approach that should thus hold constant any “aggrandizing effects” accruing from the ultimate experience of success.

Table 3. The Effect of Basic Competence Examination (SKD) Failure, No Matriculants

Note: Beta coefficients from OLS regression. Standard errors were calculated using the HC0 correction. The outcomes measure are indexed values capturing (1) Javanese preferentialism among Javans, (2) Javanese preferentialism among non-Javans, (3) regional preferentialism, (4) religious resentment, (5) perceptions of corruption, and (6) national identification; *p < 0.10, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

The outcome indices are constructed in the same manner as are the indices used in the main analysis such that the “control” group values are centered at zero. Looking at the cutpoint, and conditional on not advancing to the next stage of the recruitment process, I continue to observe attitudinal shifts between winners and losers on three out of six outcome families. Specifically, narrow losers from Java on the basic competence examination are more likely to support Javan preferentialism by a margin of 0.12 SDs. Looking at national identification, I find that narrow losers, compared with narrow winners, are less likely to reflect positively on their national identity by a margin of 0.06 SDs. Finally, turning to the effect of failing the basic competence examination on perceptions of corruption, I find that narrow losers, compared with narrow winners, are more likely to believe the recruitment process was corrupt, a shift of 0.05 SDs. Taken together, by ruling out a prominent alternative explanation, I argue that these results point to the causal significance of failure.

What Is The Effect of Public Service?

The research design also offers the ability to estimate the effect of government service on the attitudes examined in the preceding section. As discussed earlier, I compare the attitudes of individuals who were narrowly offered a job in the civil service with those individuals who narrowly missed out on being offered a job. In contrast to the previous analyses, these tests are therefore conducted on the smaller subset of applicants who had advanced to the final stage of the recruitment process (see, again, Figure 1). I present the results in Table 4.

Table 4. The Effect of Passing Specialist Competence Examination

Note: Beta coefficients from OLS regression. Standard errors were calculated using the HC0 correction. The outcomes measure are indexed values capturing (1) Javanese preferentialism among Javans, (2) Javanese preferentialism among non-Javans, (3) regional preferentialism, (4) religious resentment, (5) perceptions of corruption, and (6) national identification; *p < 0.10, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

On balance, the results indicate that the experience of being offered a position in the civil service makes individuals less likely to support the preferential treatment for members of in-groups, at least as compared with individuals who were not offered government jobs. I find that, compared with applicants from Java who narrowly failed the final civil service examination, individuals from Java who passed the final civil service examination are 0.25 SDs less likely to support policies consistent with Javan preferentialism. Once again, I find no reverse analogous effects among non-Javans—a finding that suggests that the experiences of both success and failure may induce applicants to reflect differently on the circumstances of their in-group but not necessarily on the circumstances of out-groups. Consistent with these results, I also find that individuals who narrowly passed the final civil service examination are 0.27 SDs less likely to support measures of regional preferentialism, as compared with individuals who narrowly failed the final stage. Looking at column four, I detect no evidence that the experience of being offered a position in the civil service affects individuals’ likelihood of adopting religiously intolerant attitudes.

Next, turning to column five, I show that applicants who narrowly passed the final civil service examination, when compared with those who narrowly failed, are 0.42 standard deviations less likely to indicate that the recruitment process was corrupt, bolstering the expectation that successful applicants have an incentive to say the process was free and fair to justify their own success. Finally, looking at column six, I find that individuals who are narrowly offered civil service jobs, compared with those who narrowly missed out, are 0.13 SDs more likely to positively identify with the Indonesian national identity. Again, and similar to the interpretation of the effect of public service on perceptions of corruption, it appears that success may induce candidates to affirm their support for the Indonesian national identity in a show of support for their new employer.

Are these findings driven by the actual effect of government service, or are they attributable to an aggrandizing sensation stemming from the feeling of success on the examination itself? Recall that earlier estimates established a psychic consequence of civil service examination failure in its own right. It might be the case, then, that the results observed in Table 4 reflect a reversed psychological effect at this different juncture. To adjudicate these competing possibilities, I leverage variation in successful applicants’ decision to accept a job offer. If the results are being driven by the experience of public service rather than, say, the aggrandizing effect of having passed a competitive examination, the estimates should persist when restricting the sample to those that received a job offer and comparing the attitudes of individuals who accepted with those of individuals that did not. Once again, I restrict my analysis to individuals whose scores were less than a single percentage point from an alternative disposition. Note, however, that this analysis is biased because it is subject to posttreatment bias: the decision to turn down a job offer is likely endogenous to the outcomes being measured (Montgomery, Nyhan, and Torres Reference Montgomery, Nyhan and Torres2018).Footnote 18

Biases notwithstanding, I present the results in Table 5. Importantly, the estimates are all directionally consistent with the results presented in Table 4. For two of the four results presented in Table 4, I obtain statistically significant estimates. Individuals who were narrowly offered and accepted a job in the Indonesian civil service are 0.19 SDs less likely to support preferential treatment for regional insiders, as compared with individuals who turned down a job that they were also narrowly offered. Moreover, individuals who were narrowly offered and accepted a job in the civil service are also 0.35 SDs less likely to indicate that there was corruption in the recruitment process. The results concerning perceptions of corruption are especially consistent with the expectations outlined above; having served in public service, successful applicants have an incentive to affirm the legitimacy of the institution for which they now work.

Table 5. The Effect of Accepting Government Job, Conditional on Passing Specialist Competence Examination

Note: Beta coefficients from OLS regression. Standard errors were calculated using the HC0 correction. The outcomes measure are indexed values capturing (1) Javanese preferentialism among Javans, (2) Javanese preferentialism among non-Javans, (3) regional preferentialism, (4) religious resentment, (5) perceptions of corruption, and (6) national identification; *p < 0.10, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

Robustness and Extensions

Comparative Magnitude

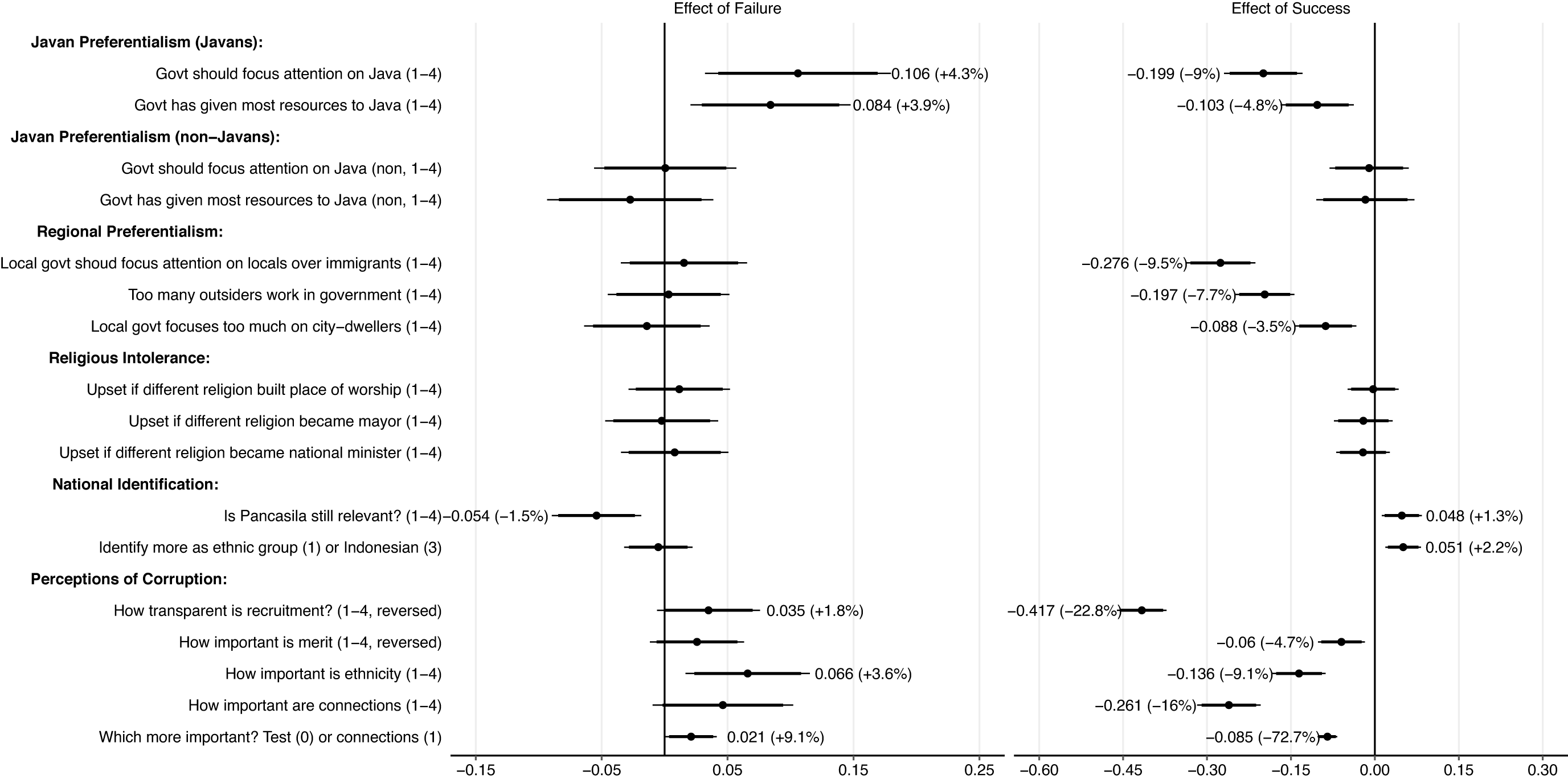

How should readers think about the comparative magnitude of the effect of examination failure against the effect of being selected for public service? To facilitate a comparison, I present the coefficients from parallel sets of analyses in which I look at the raw survey measures rather than the standardized outcomes measured in terms of standard deviations. This approach is intended to offer readers estimates that can be more easily compared. To start, the left panel of Figure 3 compares the attitudes of individuals who narrowly failed the basic competence examination with those of individuals who were narrowly successful. The first item shows that, compared with individuals from Java who narrowly passed the basic competence examination, those from Java who narrowly failed were 0.11 points more in support of the statement that “the government should focus its attention on Java,” measured on a four-point scale—a finding that corresponds to a 4.3% increase. Quizzing respondents about the extent to which Indonesia’s inclusive national ideology, Pancasila, is still “relevant” on a four-point scale reveals that those who narrowly failed the screening examination report a 0.05 percentage-point drop—a 1.5% decrease. Finally, respondents that narrowly failed the screening examination, compared with those that narrowly passed, are also 2.1 percentage points more likely to indicate that connections were more important than examination results in determining who received a job offer.

Figure 3. Comparing the Magnitude of the Effect of Success and Failure

Note: The left panel shows the effect of narrowly failing the basic competence examination on the individual and unadjusted attitudinal measures compared with the attitudes of those who narrowly passed. The right panel estimates the effect of narrowly passing the specialist competence examination compared with that of narrowly failing, also looking at the unadjusted attitudinal survey measures. Estimates include 90% and 95% confidence intervals, with text labels only presented for statistically significant differences and percentage of change over counterfactual groups included in parentheses. The tabular presentation of these results can be found in Table A17.

The right panel of Figure 3 compares respondents’ unadjusted answers to the same survey items across those who were narrowly selected for public service and those who were narrowly passed over. These estimates thus correspond to those analyses capturing the effect of public service reported above in Tables 4 and 5. Individuals from Java that were narrowly selected for a government job, compared with those narrowly not selected, are 0.2 points less in support of the statement that “the government should focus its attention on Java,” measured on a four-point scale, corresponding to a 9% decrease. Looking at the item measuring respondents’ view of the relevance of Pancasila, respondents who were narrowly selected, compared with those who were narrowly not selected, report a 0.05 increase on a 4-point scale. Finally, respondents who were narrowly selected for government jobs were 8.5 percentage points less likely to indicate that connections are more important than examination results.

In comparing the estimates in the left and right panels of Figure 3, it is clear that the substantive magnitude of the effect of public service is larger than the effect of examination failure by a factor of approximately two to three, depending on the outcome in question. However, it is worth emphasizing that the theoretical interest of this paper concerns the influence of civil service examinations on broader attitudinal currents in Indonesia. Recall that the number of people who failed the Indonesian civil service examination during 2018–2019 (3,455,639) was 19.1 times as large as the number of people who passed (180,623), suggesting the need to weight these effect sizes according to their population-level frequency. For instance, extrapolating away from the threshold suggests that the experience of failure on the basic competence examination may have nudged as many as 51,677 individuals to adopt the view that connections were more important than the test itself—more than three times greater than the 15,352 estimated to have been nudged to adopt the reverse attitude as a result of having been selected for service.Footnote 19

Attrition Bias

One concern with the findings is attrition bias. Importantly, however, there is no meaningful differential attrition across narrow winners and losers in the sample of winners and losers on the basic competence examination: 4.7% of narrow losers responded to the survey compared with 4.5% of narrow winners. Looking at the sample of winners and losers on the specialist competence examination, narrow winners are about 1.5 percentage points more likely to respond to the survey when compared with narrow losers (11.8% vs. 10.3%). This is likely attributable to the tendency for winners to be employed in a white-collar position and thus more likely to be regularly checking email, whereas losers might be unemployed or working in a blue-collar occupation. Skeptics might be concerned that this differential attrition is driving the main results. To deal with this concern, I implement the method proposed by Lee (Reference Lee2009) to create worst-case bounds for the average treatment effect, under conditions of attrition. This method relies on the assumption of monotonicity: that attrition is only unidirectionally affected by treatment assignment. In the present case, where the higher response rates are being driven by convenience of access to computers, this is a tolerable assumption.

I present the worst-case bounds for the effect of failure on the basic competence examination and the effect of passing the specialist competence examination in Table A3. All of the bounds obtained are directionally consistent with the main estimates. Interestingly, the bounds indicate that there may be an effect of failure on religious intolerance, which was not detected in the main analysis, thus suggesting that the observed null-effect on this particular outcome may be partially attributable to differential attrition. Moreover, as the method proposed by Lee (Reference Lee2009) is a particularly conservative approach, I also implement the main analysis using inverse-probability weighting to account for the differential selection into the sample. I present the results in Table A4. The results are substantively identical to those presented in the main analysis.

Alternative Specifications

Next, are the main results sensitive to alternative specifications? First, recall that the preregistered estimation strategy was intended to be implemented in local linear regression with a 5 percentage-point bandwidth. In the baseline model, I have avoided this approach to maximize interpretability of the coefficients. The presented results are also restricted to a 1 percentage-point bandwidth to minimize bias and thanks to the larger-than-anticipated sample size. I present the results from the preregistered local linear specification in Tables A5 and A6. The results presented in this section indicate that the findings reported in the baseline specification are robust to this alternative estimation strategy.

Second, I rerun the main specification including applicant age as a control variable. Recall that the balance tests revealed that—for the sample based on specialist competence examination scores—respondents who received a job in the civil service were, on average, six months older than were the respondents who did not receive a job. The reason for this imbalance is likely attributable to the attrition bias discussed above. Nonetheless, I also conduct the main analysis including respondents’ age as a control variable. I present the results in Tables A7 and A8. For all the outcomes considered, the results with the age controls are more precisely estimated than those from the naive specification presented in the main analysis. I also run the main analyses with all available demographic control variables (age, gender, location, and religion) in Tables A9 and A10 and demonstrate that the results are robust to this alternative specification as well.

Third, I also conduct an analysis to detect the sensitivity of the results to the choice of bandwidth. Recall again that I had preregistered a bandwidth of 5 percentage points but instead opted for a narrower specification in light of the unexpectedly high response rate and out of concerns of bias reduction. The sensitivity analysis follows the suggestion of Bueno and Tuñón (Reference Bueno and Tuñón2015). The results of these sensitivity analyses are presented in Figures A8 and A9 and indicate that the choice of a 1 percentage-point bandwidth is, if anything, a null-biasing choice. Particularly for the outcomes gauging religious intolerance, the sensitivity analyses reveal that for larger bandwidths, such as 5 percentage points, narrow losers appear to be more intolerant of religious out-groups than are narrow winners—a possibility that is consistent with the preregistered hypotheses.

Heterogeneous Treatment Effects

I also conduct a series of tests probing for heterogeneity in the main effects. These tests merit two caveats. First, these tests were not preregistered and should thus be interpreted as exploratory. Second, these tests probe for heterogeneity in the main effects according to measures that are likely affected by the treatment, thus making a straightforward an unbiased interpretation impossible; however, it is my view that conditional on these shortcomings these tests still convey important information.

In the first test, presented in Table A13, I examine heterogeneity according to the amount of time that respondents reported having spent preparing. If the effects are being driven by the frustrating sunk costs of futile preparation, it might be that applicants who spent more time studying would be more likely to see attitudinal shifts. Two features of this analysis are worth highlighting. First, the uninteracted coefficient is directionally correlated with the attitudes desired by the Indonesian national government, thus suggesting this measure’s reliability. For instance, applicants who reported that they studied more for the civil service examination are less likely to support preferential treatment for in-groups and more likely to identify with the Indonesian national identity. Second, and consistent with the sunk costs explanation, the negative effect of failure on the likelihood of applicants to identify with the Indonesian national identity appears to be concentrated among those who reported studying more for the examination.

In another series of tests, I examine support for the main attitudinal outcomes according to the degree to which respondents believed two categories of individuals to be advantaged on the examination—Javans and Muslims. These results are presented in Tables A11 and A12. Again, the uninteracted coefficients indicate that perceptions of disproportionate group advantage are inversely correlated with the attitudes desired by the Indonesian government among its civil servants. But in general, the observed interaction terms are insignificant.

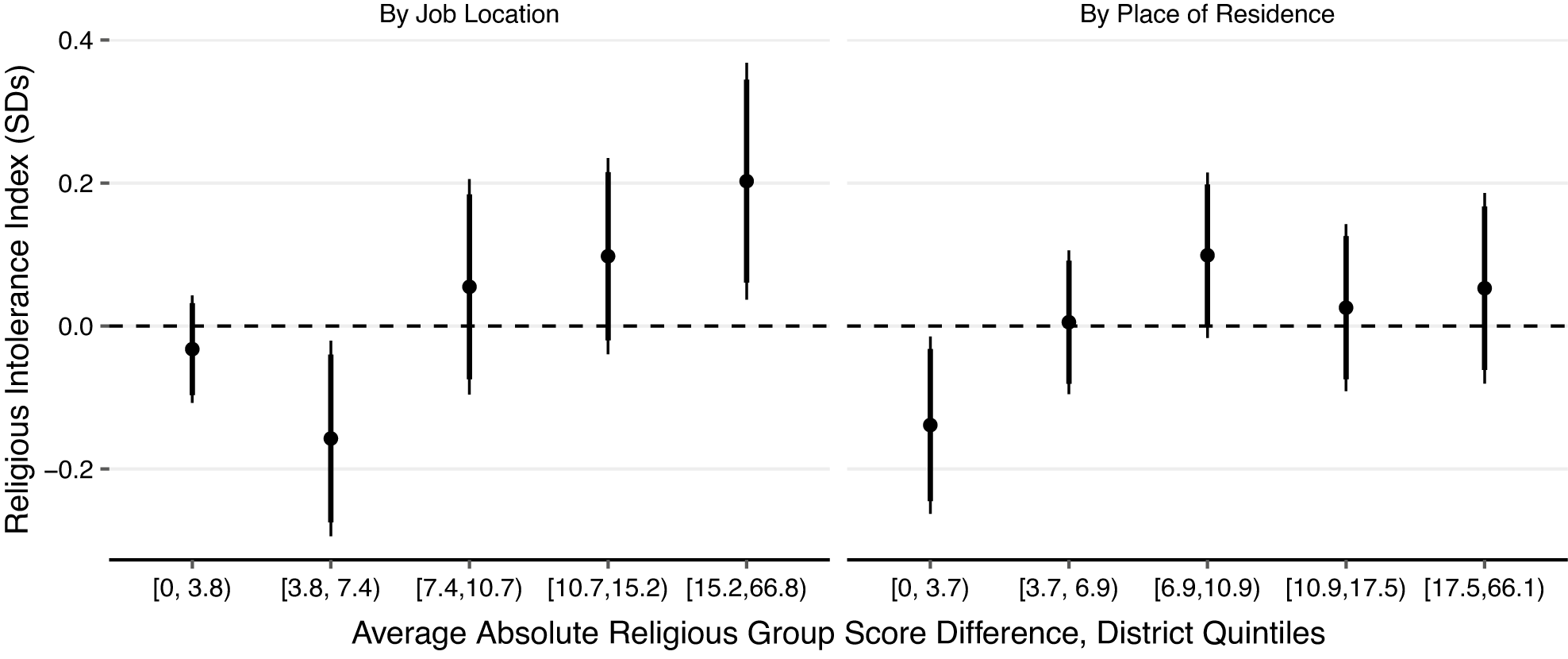

In a final test, I explore one explanation for the null result regarding the effect of having failed the basic competence examination on religious intolerance. Recent scholarly accounts have emphasized that religion has become an important cleavage in Indonesian politics (e.g., Mietzner and Muhtadi Reference Mietzner and Muhtadi2018). One possible explanation for the null result concerns the comparatively slight difference in civil service examination scores across religious cleavages: recall that Muslim applicants score only seven points (out of 500) higher than do their non-Muslim peers, on average. In other words, it might be the case that the experience of failure on the civil service examination does not motivate heightened resentment toward religious out-groups because applicants do not perceive these differences to be affecting the competition. To test this possibility, I examine heterogeneity in the main effects, subsetting observations according to the district-level average score difference between Muslim and non-Muslim applicants. I look at both district-level averages in terms of applicant place of residence and the location of the job to which the applicants are applying. Partially bolstering this possibility, in Figure 4, I show that the effect of examination failure on religious intolerance is generally higher for respondents who are applying to, or hail from, districts in which the score difference between Muslims and non-Muslims is more pronounced.

Figure 4. Effect of Failure on Religious Intolerance, by District Differences

Note: Both figures show the effect of narrowly failing the basic competence examination on religious intolerance, with estimates binned according to absolute district-level differences in average scores for Muslim and non-Muslim applicants. The left panel looks at differences in scores according to (district) job location; the right panel looks at differences in scores according to (district) place of residence. Estimates include 90% and 95% confidence intervals. The tabular presentation of these results can be found in Table A18.

Material Outcomes

As a final extension, I examine material and economic outcomes such as employment, income, and self-reported job satisfaction. Looking first at the effect of failure on the basic competence examination in Table A15, I detect no effect of narrowly failing the test on either the likelihood of individuals being currently employed or on reported job satisfaction. However, applicants who narrowly fail the basic competence examination appear to earn about 90,000 IDR(US$6) less a month than do those who narrowly passed (approximately 4.9% less). However, this effect is substantively small and appears to be driven by the small share of successful candidates who matriculated into government service. In general, the absence of substantively meaningful differences in economic outcomes for the effect of failure on the basic competence examination supports the explanation that the observed attitudinal differences stem from the psychological experience of failure on the examination.

Next, turning to the effect of public service, in Table A16, I find that individuals who narrowly passed the specialist competence examination—compared with those who narrowly failed—report significantly higher income and job satisfaction. Consistent with a large literature on the public sector wage premium, I show that individuals who were narrowly offered a job in the civil service earn about 610,000 IDR more per month compared with those who narrowly failed—a public sector wage premium of approximately 28%. Similarly, I find that narrowly selected candidates report approximately 15% higher job satisfaction than those who were narrowly not selected. One possibility is that such effects might sustain the observed attitudinal shifts as a mediating variable—for instance, if applicants who received a government job are earning more income than they otherwise would be, perhaps they have little reason to advocate for measures of in-group preferentialism.

Conclusion

I have presented evidence from a large survey of applicants for the Indonesian civil service, demonstrating that the outcomes of the recruitment examination have unanticipated yet substantively large effects on participants’ attitudes on a range of issues. I have proposed two interlocking yet distinct explanations for these results—one concerning the psychological sting of examination failure and the other concerning the experience of becoming a public servant. Focusing in particular on the former mechanism, I have argued that the experience of failure on the Indonesian civil service examination spurs unsuccessful applicants to adopt attitudes consistent with preferentialism for in-groups, a view that the recruitment process was corrupt, and an antagonistic outlook on Indonesia’s inclusivist national identity. Looking at the latter mechanism, the evidence on balance suggests that the experience of public service motivates individuals to adopt the view that the recruitment process was fair, to identify positively with an ethnically inclusive Indonesian national identity, and to be less likely to support preferential treatment for in-groups.

The chief contribution of this research relates to identifying the effect of examination failure on salient attitudes, which addresses both old and new debates in comparative politics and political science. On the first count, these findings contribute to a literature documenting unintended (or uninterrogated) consequences of public policy interventions. In this sense, these findings call attention to the concern that “the outcome one studies affects the answer one gets” (Geddes Reference Geddes2003; Kramon and Posner Reference Kramon and Posner2013). For political scientists interested in the institutional design of bureaucracy, this research calls attention to outcomes beyond bureaucratic performance and service delivery. The unifying claim of this paper is that outcomes such as solidarity and social cohesion can be affected by the institutions used to select civil servants. Balancing the potentially deleterious effects of examinations on these outcomes against the salutary effects of examinations on service delivery should be foregrounded in future research. For instance, light-touch policy interventions, such as residency requirements stipulating that applicants must reside in the district to which they are applying, may help undermine the dynamics of in-group–out-group competition that give rise to the reported effects. To be clear, the argument presented here does not dispute—and is not able to evaluate—the consensus that the merit-based recruitment of civil servants leads to better measures of service delivery, particularly as compared with countries where patronage is rampant (Barbosa and Ferreira Reference Barbosa and Ferreira2019; Colonnelli, Prem, and Teso Reference Colonnelli, Prem and Teso2020). Instead, my intention is to unearth the costs at which these gains in performance might come in terms of unanticipated attitudinal shifts.

Second, this work offers an empirical intervention into a growing body of work in normative political theory questioning the virtues of meritocracies (Markovits Reference Markovits2020; Sandel Reference Sandel2020). These accounts have taken aim at the American model of higher education, arguing that an overreliance on test scores has perpetuated existing class hierarchies, inspiring the anger of failed applicants. Looking at a wholly distinct empirical context—meritocratic recruitment of civil servants in Indonesia—I find evidence in support of some of the arguments articulated by these earlier inquiries. Failure on high-stakes examinations does appear to nudge applicants to the Indonesian civil service to adopt attitudes antagonistic to the institution itself and toward some out-groups, consistent with the idea that “among the losers,” meritocracy leads to “humiliation and resentment” (Sandel Reference Sandel2020, 23). This parallel likely stems from both Indonesia and the United States reporting high levels of group-based inequality such that meritocratic selection procedures are increasingly viewed as a tool to maintain the prevailing distribution of scarce resources among competing groups—whether in classrooms or bureaucracies alike. The findings presented in this paper also raise the possibility that the procedures of meritocratic selection—heralded as a solution to previously corrupt practices—could be a self-defeating institution: the sting of failure under examinations may generate disaffection among applicants who come to view the process as illegitimate as a means of exculpating their role in their disappointment.

The findings presented in this paper suggest at least two lines for future inquiries. First, it seems likely that the experience of failure might affect meaningful political attitudes not considered here—such as voter preferences or support for democratic institutions. But more relevant for the theory evaluated in this paper is the possibility that examination failure motivates behavioral outcomes—such as applicants’ participation in protests or riots. Although purely circumstantial, in Figure A7, I present evidence suggestive of this possibility, showing that episodes of communal violence sparked by conflicts over the recruitment of civil servants have increased over the same period that Indonesia has become more meritocratic in its bureaucratic recruitment.

Second, future investigations should examine the generalizability of the findings presented here. In settings where group-based inequality is high—such as Brazil, India, and the United States—many of the predictions surrounding the generic effects of examination failure should hold. It also may be the case that the findings pertaining to perceptions of corruption might still hold in comparatively more homogenous cases found in East Asia and Scandinavia. Moreover, the effects of examination failure reported here likely only obtain in high-stakes settings. At least for civil service examinations, in particular, this means the results may only be generalizable to lower- and middle-income countries, where public sector employment is often the only apparent vehicle to financial security (Finan, Olken, and Pande Reference Finan, Olken, Pande, Banerjee and Duflo2017). Finally, to obtain more clarity over the precise mechanisms driving the results presented in this paper, future applications of the research design may benefit from fielding the survey both before and after examination outcomes are known to applicants. Nonetheless, it is my hope that the empirical strategy used in this research is sufficiently general to be globally applicable.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055422001149.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research documentation and data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the American Political Science Review Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/RDU9JR. Limitations on data availability are discussed in the text and in the supplementary materials. The preanalysis plan associated with this manuscript can be found on the EGAP registry (#20200309AA).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

For comments on previous versions, I thank Jennifer Bussell, Thad Dunning, Andrew Little, Cecilia Hyunjung Mo, Saiful Mujani, Neil O’Brian, Tom Pepinsky, Bhumi Purohit, Alexander Sahn, and Jason Wittenberg, as well as seminar participants at APSA, CaliWEPS, Cornell, GIGA, LKY School of Public Policy, MPSA, NIU, NUS, SEAREG, Stanford, and UC Berkeley. For support in implementing this project, I thank the staff at the Badan Kepegawaian Negara—especially Auditya Nugraha Dhaspito, Eka Kemastuti, and Heni Sri Wahyuni. I also thank Claudia Syarifah and Ibnu Rasyid Welas for excellent research assistance.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The author declares no ethical issues or conflicts of interest associated with this research.

ETHICAL STANDARDS

The author declares the human subjects research in this article was reviewed and approved by UC Berkeley’s Committee for Protection of Human Subjects (IRB Protocol #2020-02-12976). The author affirms that this article adheres to the APSA’s Principles and Guidance on Human Subject Research.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.