In 1975, Mozambique gained independence from Portugal after being embroiled in a ten-year liberation struggle. Soon thereafter, the newly independent country faced new instability. Mozambique’s neighbor Rhodesia (present-day Zimbabwe) sought to ward off liberation movements that benefited from their sanctuary in Mozambique. Rhodesian intelligence forces trained discontented Mozambicans who had fled to Rhodesia in 1974 and formed an armed group, first under the name Mozambican National Resistance, or Movimento Nacional de Resistência (MNR), and later under the moniker by which it is known to this day, Renamo.Footnote 1 From 1981 onward, Apartheid South Africa also began supporting Renamo to destabilize its neighbors, since Mozambique had become an important sanctuary for the anti-apartheid movement, the African National Congress (ANC).Footnote 2

After Zimbabwe’s independence in 1980 and with South African support, Renamo expanded its activities across the entire country and gained in strength. In the early 1980s, Renamo moved into the central and northern regions and occupied vast areas, thereby threatening a partition of the country between north and south along the Zambezi River valley.Footnote 3 Popular discontent with Frelimo’s restructuring of economic, social, and political relations, in particular in the northern provinces, fueled the ensuing war.

Frelimo and Renamo were only willing to engage in a peace process after the signing of a nonaggression pact, the N’komati Accord, between Mozambique and South Africa in 1984, the end of Malawi’s assistance to Renamo in 1986, and an apparent military stalemate in 1988–89. Peace negotiations culminated in the signing of the peace accord on October 4, 1992. Overall, it is estimated that the war cost over one million lives and displaced almost five million people of a total population of about thirteen million at the end of the war, both as a consequence of fighting and war-induced famine and disease (Hanlon Reference Hanlon1996, 16). The war took a heavy toll on infrastructure, with 60 percent of primary schools and 40 percent of health clinics destroyed in 1992 (Hanlon Reference Hanlon1996, 15).

This chapter analyzes the origins and the evolution of the war to provide context for the formation, diffusion, and mobilization of community-initiated militias. I analyze both internal divisions and regional contexts. I put particular emphasis on the relations between the armed actors and the population and the patterns of violence that – as I explain in more detail in subsequent chapters – influenced community initiatives to form militias.

Throughout the chapter, I make three interrelated, arguments. First, the war was a war over people. The control of the population became an end in itself rather than a means to expand control over territory. Kalyvas (Reference Kalyvas2006) argues that selective violence by armed groups – the incumbent or insurgent – in irregular civil wars deters people from providing intelligence to the other side, which improves security in areas under control. Violence thus serves to strengthen civilian support, which allows for the expansion of territorial control. In the late 1980s in Mozambique, however, during a time characterized by a military stalemate between the conflict parties, Frelimo and Renamo developed a different strategy. As they were unable to significantly expand their control over territory, both sides forcibly resettled the population as a strategy of war to consolidate the areas already under their control. Rather than using selective violence to change people’s incentives and deter disloyalty, Frelimo and Renamo chose brute force – population resettlement – to make disloyalty impossible (Zhukov Reference Zhukov2015). I explore the evolution of this instrumental relation with civilians and delineate its consequences for the dynamics of war.

Second, both Frelimo and Renamo attempted to consolidate their control over people by involving residents in gathering intelligence and defending the local population, which led to the militarization of society.Footnote 4 Frelimo’s counterinsurgency strategy was built on assigning military tasks to state-initiated militias who initially served political purposes. The government also trained civilians for local defense. Renamo enlisted traditional authorities and formed local police forces to ensure collaboration of the people in areas under their control. In developing this argument, I unpack how Frelimo’s internal conflicts and domestic politics after independence put domestic and regime security at center stage of the party’s political agenda.

Third, although Frelimo’s military strategy was built on community defense, it failed to protect the population from insurgent violence. Renamo’s military strategy was meant to control the local population rather than protect it from violence. Community residents thus suffered from high levels of indiscriminate and collective violence perpetrated by both sides. Due to the lack of material and ammunition in the central and northern regions, Frelimo and Renamo fought a “war of avoidance,” attacking the population in zones under enemy control rather than engaging in direct battle (Legrand Reference Legrand1993, 98). As a consequence, community residents developed their own means of protection, such as peace zones and community-initiated militias to patrol residential areas. I analyze how characteristics of violence helped to form community-initiated militias and show how far these militias relied on preexisting social conventions for the spiritual dimension of the war.

The first section analyzes the conflicts that evolved within Frelimo before and after independence. These internal struggles created popular discontent, which, in many areas, fueled the war at the local level. The second section assesses the impact of regional factors that gave rise to the formation and expansion of Renamo. The third section examines how Frelimo’s counterinsurgent strategy improved or deteriorated the movement’s relationship with the population. To control “internal and external enemies” of the state, Frelimo militarized society and Mozambique evolved into a police state. The fourth section reviews the extent to which Frelimo’s inadequate response to the threat posed by Renamo led communities to develop their own responses to Renamo. One such response was the formation of the Naparama, the independent militia that later supported Frelimo in its counterinsurgent effort in Zambézia and Nampula provinces. The final section provides a brief overview of the peace process and the legacies of the war.

4.1 Anticolonial Struggle and Independence

When Mozambique gained independence from Portugal in 1975, the FRELIMO liberation movementFootnote 5 came to power, and it worked hard to retain that power. As a political movement, and subsequently as a political party, Frelimo recognized the importance of unity (De Bragança and Depelchin Reference De Bragança and Depelchin1986). However, internal divisions about goals and strategies evolved, which enabled Rhodesia and Apartheid South Africa to build support for their regional agenda among discontented Mozambicans. From independence onward, the regime treated such “enemies of the revolution” harshly. Frelimo was able to consolidate its power over the long term by slowly creating a police state that made use of violence against those disloyal to its political project (Macamo Reference Macamo2016; Bertelsen Reference Bertelsen2016). A “politics of punishment” (Machava Reference Machava2011) emerged that did not distinguish between internal and external security, giving rise to an increasing militarization of the party and society that also influenced Frelimo’s counterinsurgency response to Renamo.

4.1.1 The Formation of FRELIMO and the Beginning of the Liberation Struggle

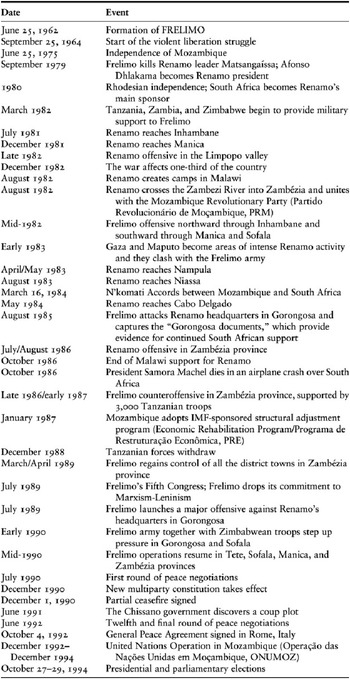

Mozambican historiography – including the way in which Frelimo has told its own story – has often been used for political purposes and is thus contested (Cahen Reference Cahen2008a). For Frelimo, Mozambique’s official historiography has served the purpose of promoting and legitimating a unified movement and nation-state. A case in point is the beginning of the liberation struggle. FRELIMO was formed on June 25, 1962 in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, with Eduardo Mondlane – who had been educated in the United States and had worked for the United Nations – as the movement’s first president.Footnote 6 The violent liberation struggle began in 1964, with, according to the official history, the infiltration of 300 FRELIMO fighters into Mozambique from Tanzania. On September 25, 1964, FRELIMO attacked the Portuguese administrative post at Chai in the northern region of Cabo Delgado (see map in Figure 4.1 and an overview of major historical events in Table 4.1). Alberto Chipande, Minister of Defense from 1975 to 1994, supposedly fired the first shot (Muiuane Reference Muiuane2006, 31–43). Contrary to this official account, factions of movements that were not fully integrated into FRELIMO had already launched small-scale assaults in July and August 1964 in Zambézia (Cahen Reference Cahen1999, 45). These contradictions about the beginning of the liberation struggle hint at Frelimo’s “victorious historiography,” which demonstrates Frelimo’s attempt at a triumphalist, coherent, and conflict-free chronicle of the liberation struggle and its aftermath (De Bragança and Depelchin Reference De Bragança and Depelchin1986, 165).

Figure 4.1. Map of provincial boundaries in Mozambique

Note: Cartography by Sofia Jorges

Table 4.1. Overview of major events in recent Mozambican history

Although the Portuguese government responded to the beginning of the armed struggle with heavily armed troops and a sophisticated network of secret police agents, FRELIMO gained popular support and made quick advances in Cabo Delgado, Niassa, and Tete provinces. The largest Portuguese counterinsurgency campaign – Operation “Gordian Knot” from May to August 1970 – failed due to FRELIMO’s strong support among the peasants from the Makonde, an ethnic group in Cabo Delgado (Hanlon Reference Hanlon1984, 35).Footnote 7 When FRELIMO advanced into the central provinces,Footnote 8 the Portuguese responded by massacring the population. One of the most notorious massacres occurred in December 1972, when elite troops killed 400 people from the village of Wiriamu in Tete province (Hanlon Reference Hanlon1984, 36; Dhada Reference Dhada2016).Footnote 9

The anticolonial struggle was not decided on the battlefield but ended following domestic developments in Portugal. Out of concern for Portuguese national debt and the danger of becoming embroiled in wars that could not be won, young army officers in Portugal formed the Armed Forces Movement, which overthrew the Portuguese dictatorship in April 1974 (Isaacman and Isaacman Reference Isaacman and Isaacman1983, 106). The “Carnation Revolution,” as it was later called, accelerated the decolonization process across the Portuguese Empire, including Mozambique (Lloyd-Jones and Pinto Reference Lloyd-Jones and Pinto2003). The coup made negotiations possible between the new Portuguese government and FRELIMO, culminating in the signing of the Lusaka Accord on September 7, 1974, granting Mozambique independence nine months later. After the transitional government period, FRELIMO’s then president, Samora Moíses Machel, became the first president of independent Mozambique.

4.1.2 Internal Conflict within FRELIMO

During the independence struggle, FRELIMO faced internal conflicts about the goal and strategies of the movement, but debate remains regarding the precise divisions. According to the movement itself and some analysts, the main rift was over the final objective – national independence or the socioeconomic restructuring of society. De Bragança and Depelchin (Reference De Bragança and Depelchin1986) – adopting the official Frelimo party language – call the first goal the “reactionary” line and the second the “revolutionary” line, which implies a class conflict within the movement between a black nationalist bourgeoisie and the revolutionary vanguard.Footnote 10 Echoing de Bragança and Depelchin’s comments about Frelimo’s conflict-less “victorious historiography,” Hanlon (Reference Hanlon1984, 28) remarks that in reality, these two lines were difficult to separate. The more conservative line attracted many supporters and was not as homogenous as Frelimo attempted to portray it in its official history. Cahen (Reference Cahen1999, 46n27) argues that rather than a conflict between the bourgeois and the revolutionary class, the divisions within FRELIMO represented a conflict with social and regional dimensions: the “rural modern merchant elite” among the Makonde ethnic group in the north was in conflict with the “urban bureaucratic petty-bourgeois elite of the Frelimo military” among the Shangaan, the assimilados (assimilated, Mozambicans with Portuguese privileges), and the mulattoes in the southern cities – these were not merchants, but worked in the bureaucracy or other services.Footnote 11

This internal conflict influenced how the movement defined the enemy, the tactics of armed struggle, and the type of society to be constructed in the “liberated zones” during the armed struggle against the Portuguese (Isaacman and Isaacman Reference Isaacman and Isaacman1983, 86; Frelimo 1978, 4–21; Cahen Reference Cahen2008a). Much of the evolution of FRELIMO’s strategies, however, was a mixture of ideology and pragmatism. In terms of the military strategy, different factions advocated for urban uprisings, short-term insurrection in the countryside, or long-term mobilization of the rural masses. Yet developments inside and outside of Mozambique made the first two options unviable.Footnote 12 Thus, long-term guerrilla activity became the major strategy of FRELIMO’s armed struggle (Isaacman and Isaacman Reference Isaacman and Isaacman1983, 88–89; Hanlon Reference Hanlon1984, 27).

The evolution of FRELIMO’s goals and strategies led to the marginalization of prominent leaders with alternative visions. The conflict escalated after decisions made at the 1968 Second Congress reflected what FRELIMO termed the “revolutionary line.” Lázaro N’kavandame, the leader of the Makonde in Cabo Delgado, from where many liberation fighters originated, defected to the Portuguese in 1968. He was identified by Frelimo as representing the “reactionary line.” Moreover, Uria Simango, who had hoped to become president at the Second Congress, was expelled from the movement in 1970 after the assassination of FRELIMO leader Eduardo Mondlane in Dar es Salaam in February 1969 (Cabrita Reference Cabrita2000, chapter 11; Cahen Reference Cahen2008a).Footnote 13 Those with “revolutionary” visions consolidated their power after Mondlane’s death, but conflicts continued to be suppressed rather than resolved. In 1970, Samora Machel, a representative of the “revolutionary line,” became FRELIMO president and Marcelino dos Santos vice-president.Footnote 14

These internal conflicts resurfaced at independence. The Lusaka Accord granted FRELIMO a preferential position in postindependent Mozambique as the “sole and legitimate representative of the Mozambican people.” Immediately after the signing of the accords, about 250 right-wing white settlers took over the radio station and newspaper in Lourenço Marques and sought to declare independence unilaterally (Hall and Young Reference Hall and Young1997, 45). Uria Simango, who had formed a new political party after returning to Mozambique in 1974, and others called for elections during which FRELIMO would have to compete with opposition parties at independence (Cabrita Reference Cabrita2000, 80). However, the turmoil only lasted for a few days. In coordination with the Portuguese, Rhodesians and South Africans, FRELIMO suppressed the revolt, arrested opposition leaders and sent them to reeducation camps in Niassa and Cabo Delgado provinces (Cabrita Reference Cabrita2000, 81–84).Footnote 15

4.1.3 Origins and Consequences of Frelimo Policy after Independence

Frelimo’s policies that sought to restructure society and the economy after independence are often cited as a source of discontent among the population and support for Renamo.Footnote 16 As the “revolutionary” camp came to dominate FRELIMO, the movement officially adopted the objective of a socialist, anticolonialist, and antifascist revolution and the liberation of all of Mozambique (Hanlon Reference Hanlon1984, 34).Footnote 17 In the “liberated” zones in the northern provinces of Cabo Delgado and Niassa, FRELIMO put these ideas into practice and educated the peasants politically, formed communal villages with collective agriculture, and provided rudimentary education and health services to the villagers (Hanlon Reference Hanlon1984, 29). Antiracism, anti-tribalism, and the negation of the very existence of ethnic groups shaped the policies to achieve national unity (Isaacman and Isaacman Reference Isaacman and Isaacman1983, 112–13; Cahen Reference Cahen, Braathen, Bøås and Sæther2000, 168). FRELIMO structures replaced the existing traditional leadership, as the movement considered the regulados (chieftaincies), which had been the main pillar of the colonial local administrative system, collaborators of the Portuguese.

The newly introduced economic and social policies right after independence had important consequences for the economy. FRELIMO’s antiracist stance implied that it did not seek to alienate the white population. However, the nationalization of education, medicine, law, and funeral services a month after independence led to the flight of many white settlers out of fear for their businesses and personal well-being. Businesses were left behind without functioning equipment or trained managers, which shattered whole economic sectors (Hanlon Reference Hanlon1984, 46–49).

To stop the erosion of the economy and promote unity of the Mozambican people, FRELIMO created transitional Dynamizing Groups (Grupos Dinamizadores, GD). These groups, consisting of eight to ten people in every village, neighborhood, and workplace, were intended to provide political education and motivation to the population. The GDs were crucial in those regions that had remained untouched by FRELIMO political activity during the liberation struggle (Isaacman and Isaacman Reference Isaacman and Isaacman1983, 106–7). They served as party cells, administrators, local leaders, and providers of public services at the same time: “More than anything else, it was the GDs that introduced Mozambique to Frelimo and to ‘people’s democracy,’ and it was the GDs that kept the country running” (Hanlon Reference Hanlon1984, 49).Footnote 18 The mass organizations for workers, women, and youth, introduced before and after the party’s Third Congress in 1977, took over many of the GDs’ activities. In the late 1970s, Frelimo eliminated the GDs in the countryside and completely replaced them with the new party structures (Isaacman and Isaacman Reference Isaacman and Isaacman1983, 124).

The party’s Third Congress in 1977 marked Frelimo’s official turn to Marxist-Leninist ideology, which had important implications for how the movement defined its own role vis-à-vis Mozambique’s citizens. At the congress, the party transformed itself from a mass movement into a vanguard party that served as the main body overseeing state and society (Hanlon Reference Hanlon1984, 138). The restructuring of the economy included the “socialization of the countryside,” which meant the construction of communal villages, agricultural cooperatives, and the creation of productive state farms from abandoned settler plantations and estates (Isaacman and Isaacman Reference Isaacman and Isaacman1983, 148). Beyond these economic transformations, Frelimo aimed at creating a “new man” to overcome the “viciousness” of colonial society and the capitalist bourgeoisie. In this vein, Frelimo abolished the remnants of the system of traditional leadership and prohibited the exercise of all forms of religion – “obscurantism” in Frelimo’s official language. Cahen (Reference Cahen2006) sees in these economic, social, and political transformations the pursuit of an authoritarian modernization project that pursued national unity by creating a “new man” completely separated from African peasant society. Sumich (Reference Sundberg and Melander2013, 100) emphasizes the exclusionary nature of this new conception of citizenship, as only those who joined “the wider collective under Frelimo’s leadership” became “true” citizens. All others were declared “enemies of the people” (Machava Reference Machava2011). Such “enemies” became targets of campaigns such as Operação Produção (Operation Production) and were sent to reeducation camps to ensure that all members of society contributed their labor to the collective good (Machava Reference Machava2018).

As part of the economic and social policies, the construction of communal villages was Frelimo’s most ambitious and interventionist project in rural areas. It gave rise to a scholarly debate on the degree to which its implementation contributed to peasants’ alienation from Frelimo and their inclination to support Renamo, mainly because of the contradiction between Frelimo’s ambitions and the realities of their implementation. The construction of communal villages reflected the party’s various economic, political, and social aims.Footnote 19 Communal villages sought to modernize the countryside by resettling the previously dispersed population, thereby improving access to health care and education and increasing productivity by collectively producing cash crops.Footnote 20 The involvement of peasants in various revolutionary institutions provided spaces for their political indoctrination (Hanlon Reference Hanlon1984, 122; Isaacman and Isaacman Reference Isaacman and Isaacman1983, 152–53). All in all, the organization of all residents into communal villages extended the state’s reach into the periphery and made society “legible,” similarly to such processes in Tanzania and other countries (Scott Reference Scott1998). It facilitated close control over citizens to recognize and identify deviant behavior, which proved useful when internal and external security threats increased in the 1980s.

Recognizing the far-reaching interventionist nature of communal villages, many communities did not support building them, or even resisted building them outright. Nampula province saw the construction of a large number of communal villages (Isaacman and Isaacman Reference Isaacman and Isaacman1983, 153). However, as Hanlon (Reference Hanlon1984, 128) notes, “most villages result[ed] from war and natural disaster and involve[d] a high degree of compulsion.” Most villages in Nampula were created when the war reached the province, mostly by the army (Dinerman Reference Dinerman2006, 22; Minter Reference Minter1994). In Cabo Delgado, Niassa, and Tete, Frelimo superimposed the villages on the structure of colonial strategic hamlets and settled refugees from Malawi and Tanzania in these villages (Isaacman and Isaacman Reference Isaacman and Isaacman1983, 153). In Gaza, Frelimo settled victims of the 1977 floods in communal villages (Roesch Reference Roesch1992).

Several reasons explain why support among the population for communal villages was low. Productivity in the new villages was low, which decreased their appeal.Footnote 21 Peasants resisted changing their forms of production in the long term to suit being organized into agricultural cooperatives (Isaacman and Isaacman Reference Isaacman and Isaacman1983, 155–56). Moreover, traditional leaders and capitalist farmers rejected resettlement. The communal villages also lacked the necessary technical and financial support, as state farms and urban projects received more government resources than communal villages and peasant farming (Hanlon Reference Hanlon1984, 123–24; Hermele Reference Hermele1986). Thus, rather than strengthening the peasant sector, Frelimo’s policies alienated the middle peasants and failed to adequately support poor peasants (Bowen Reference Bowen2000; Hanlon Reference Hanlon1984).Footnote 22

As a consequence, contradictions arose between the ideal of the communal villages and its implementation. The highly idealistic, bureaucratic, and technocratic idea of the communal villages did not correspond with the everyday needs of the people (Cahen Reference Cahen1987, 51). Peasants had to leave their ancestral land and travel too far to reach their individual plots. While it could be argued that the project was driven by good humanist intentions, its implementation chiefly served the state’s aim of ensuring social control (Geffray Reference Geffray1990, 35–36). In fact, communal villages became highly organized and vigilante groups and militias helped control the population, which contributed to the goal of forming “true” and compliant citizens (cf. Sumich Reference Sundberg and Melander2013). Resettlement to the villages was increasingly conducted by force, which further decreased the villages’ appeal (Bowen Reference Bowen2000, 15; Minter Reference Minter1994).

These contradictions prompted a debate among scholars on the degree to which villagization fueled the war on the local level. Most prominent is Christian Geffray’s (Reference Geffray1990) study of the Erati district in Nampula province, in which he argues that Renamo destroyed villages and sent residents to their previous homes to generate popular support. However, other analysts argue that different policies were more relevant in generating Renamo support. For example, Frelimo’s reliance on mechanized state farms rather than family agriculture and the failure to rebuild a trading network for peasants’ surplus production created discontent (Fauvet Reference Fauvet1990). Still others argue that Renamo’s success is largely due to external support from Rhodesia and South Africa (Minter Reference Minter1994). The following section explores these different arguments in more detail.

4.2 The Formation and Expansion of Renamo

There is considerable debate over the origins of the rebel movement Renamo, and in particular over the balance between external influences and internal circumstances that contributed to Renamo’s emergence. The historical evidence shows that both were necessary to bring about an armed opposition movement. However, when analyzing Renamo’s early history, it becomes clear that external support was more important for the early phases, while internal support was essential for later phases of the war. Significant support from Rhodesia facilitated the formation of Renamo, and Apartheid South Africa ensured the organization’s survival beyond Rhodesian independence in 1980. Popular support within Mozambique became crucial in the mid-1980s when Renamo expanded to the northern provinces.

4.2.1 Regional Dynamics and Discontent among Mozambicans Abroad

The formation of Renamo was closely linked to regional political dynamics, in particular to Rhodesian counterinsurgency operations during the country’s liberation struggle.Footnote 23 During the Mozambican war of independence between 1964 and 1974, FRELIMO-infiltrated areas within Mozambique provided neighboring liberation movements such as ZANLA sanctuary and ground for operations. Upon gaining independence, Mozambique continued supporting ZANLA and imposed sanctions on Rhodesia.Footnote 24 Renamo’s roots lay in the local armed units that Rhodesia had formed and supported within Mozambique to counter the Mozambican support of Zimbabwean rebel activity (Vines Reference Vines1991, 10).Footnote 25 The Rhodesian military and intelligence agency began its suppression of opposition activities in Mozambique long before Mozambique’s independence.Footnote 26 In November 1973, the Rhodesian army, in cooperation with the Rhodesian Central Intelligence Organization (CIO), formed a special cross-border strike force of about 1,800 men, the Selous Scouts. This group attacked ZANLA camps inside Mozambique shortly thereafter (Minter Reference Minter1994, 124).Footnote 27 Rhodesia continued to attack ZANLA camps even after Mozambican independence in 1975.Footnote 28

Recruiting among exiled Mozambicans, the Rhodesians slowly built an organization that could operate independently against their enemies, so that the government could plausibly deny involvement in Mozambique’s internal affairs. Instead of limiting its operations to those against ZANLA, the new organization would direct its attacks against those that supported the Zimbabwean liberation movements – the Mozambican government.Footnote 29 The CIO started a radio program – Voz da África Livre (Voice of Free Africa) – in July 1976 in cooperation with exiled Mozambicans.Footnote 30 The program aimed to reach those who had stayed in Mozambique and were stripped of the right to vote or sent to reeducation camps in northern Mozambique.Footnote 31

Renamo was prepared to conduct its operations more autonomously soon after Mozambican independence. Its first independent operations occurred in December 1978, after the liberation war in Rhodesia had intensified (Robinson Reference Robinson2006, 105–6).Footnote 32 By 1979, Renamo operated from within Mozambique, from camps close to the Rhodesian border, and its activities concentrated on Manica and Sofala provinces (Hanlon Reference Hanlon1984, 221). Attacks in these first years of Renamo activity included ambushes on civilian buses and army vehicles and attacks on Frelimo positions and other military targets.

However, pressure from the Mozambican army and developments within Rhodesia made Renamo’s future uncertain. After the Lancaster House talks on the future of Zimbabwe-Rhodesia had opened in London in September 1979, the Mozambican army started an offensive against Renamo’s base on top of the Gorongosa mountain in Sofala province. During this offensive, Renamo leader Matsangaíssa was killed. When the Lancaster House agreement was signed and Zimbabwean elections were set for February 1980, the CIO head for Mozambique asked the remaining Renamo men in Zimbabwe where they wanted to go – to South Africa as exiles or to Mozambique; they all chose Mozambique. Renamo troops within Mozambique were sent to the Sitatonga base in southern Manica. However, the Frelimo army captured the Sitatonga base in late June 1980, killing almost 300 men and capturing 300 more, thus largely destroying the Renamo organization (Hanlon Reference Hanlon1984, 221).

Despite Frelimo pressure and the end of Rhodesian support, Renamo initially survived thanks to increased South African support. Following an internal power struggle that killed further Renamo troops and commanders, Afonso Dhlakama became the organization’s new president. Dhlakama was a former FRELIMO commander who was ousted from the army at the same time as his predecessor, the recently assassinated Matsangaíssa. Renamo secretary-general Orlando Cristina supported Dklakama and ensured South African support for Renamo (Hanlon Reference Hanlon1984, 222). The South Africans provided training at a camp in the Transvaal and resumed broadcast of the Renamo radio station. South African support via equipment and weapons enabled Renamo to resume activity in most of the sparsely populated areas of Manica and Sofala provinces by 1981 (Hanlon Reference Hanlon1984, 225).Footnote 33

4.2.2 Renamo’s Expansion across Mozambique

Starting out as a small counterinsurgent force, Renamo grew substantively with South African support.Footnote 34 Membership within Renamo increased from 76 in September 1977 to more than 900 by the end of 1978 (Cabrita Reference Cabrita2000, 149, 154). When South Africa became Renamo’s main external supporter in early 1980, the organization had about 2,000 fighters (Robinson Reference Robinson2006, 122), growing to 7,000 in December 1980 and 10,000 in February 1981 (Johnson, Martin, and Nyerere Reference Johnson, Martin and Nyerere1986, 19). Cahen (Reference Cahen2019, 144) estimates a troop size of 12,300 by the end of 1984.

In the early 1980s, the war spread from the center to the southern and northern regions, affecting approximately one-third of the country by December 1982 (see Table 4.1 for an overview of important events).Footnote 35 In 1981, Renamo’s area of operation was limited to the territory between the Beira corridor to the north and the Save River to the south. In July 1981, a contingent of 300 men crossed into Inhambane province further south (Cabrita Reference Cabrita2000, 192–94). By December 1981, another contingent headed by the commander Calisto Meque had advanced to northern Manica province close to Tete province (Cabrita Reference Cabrita2000, 199). During the first half of 1982, Renamo reestablished its headquarters in the Gorongosa mountains in northern Sofala, because the Frelimo army had destroyed Renamo’s base in Chicarre in southern Manica close to the Zimbabwean border. While a Renamo offensive in the Limpopo valley in the south aiming to cut the capital Maputo off from the rest of the country failed in late 1982,Footnote 36 the creation of camps in Malawi in August 1982 proved successful for the extension of the northern fronts to Tete and Zambézia provinces (Hanlon Reference Hanlon1984, 226).Footnote 37 However, Mozambican Foreign Minister Joaquim Chissano’s successful initiative to end Malawian support to the rebels and the army’s capture of the main rebel base in Zambézia curtailed Renamo activity in the north (Hanlon Reference Hanlon1984, 226–27).

In response, Renamo started another offensive to move north in early 1983, finally reaching all northern provinces by early 1984. The organization sought to secure supply routes by land, air, and sea.Footnote 38 Renamo also reactivated the Malawi bases and spread across Zambézia and into Nampula and Niassa provinces. About 350–500 men entered Nampula in April 1983 from the Renamo base near the Namuli mountains in Zambézia province (Cabrita Reference Cabrita2000, 218; Do Rosário Reference Do Rosário2009, 305).Footnote 39 In August 1983, a contingent of 150 men from the Milange base in Zambézia crossed into Niassa province and established a base there. In May 1984, Renamo reached Cabo Delgado. By mid-1984, the war had reached all ten provinces of Mozambique.

4.2.3 Renamo’s Goals and Strategies

Rhodesian and South African support shaped Renamo’s goals and strategies from the beginning, albeit in slightly different directions (Hanlon Reference Hanlon1984, 227–28). Rhodesia’s interest in Renamo tended to focus on the gathering of intelligence on the Zimbabwean liberation movements. Thus, the Rhodesians had to foster a relatively good relationship with the local population and only conducted small-scale attacks. South Africa, in contrast, was more interested in destabilization and the destruction of economic targets. It therefore did not require such close cooperation with the local population.

Nevertheless, there is ample evidence that Renamo’s sponsors and leaders never had a unified view of the ultimate goal of Renamo’s activities. They did not expect that Renamo would develop its own independent goals, which also changed over time. Even within the Rhodesian intelligence community, aims varied from intelligence gathering, destabilization, to even considering Renamo as an alternative Mozambican government (Robinson Reference Robinson2006, 108). Similarly, among the South African security forces and the Apartheid government, conflict emerged between different objectives, which came into conflict and shaped the changes in South African security policy toward Mozambique in the 1980s.Footnote 40

Renamo’s leadership defined its own goals more distinctly after the group’s survival was secured through increased South African support, and after the movement sought closer contacts to the population within Mozambique following Zimbabwe’s independence (Cahen Reference Cahen2008b, 164). In 1981, the head of Renamo’s external relations, Orlando Cristina, and Renamo’s European spokesperson, Evo Fernandes, wrote a Manifesto and Program of Renamo (Renamo 1988), which clearly positioned Renamo as a pro-West, anticommunist organization. The devised goals included multiparty democracy, private enterprise, and rule of law (Vines Reference Vines1991, 77). Orlando Cristina and Renamo’s president Afonso Dhlakama also conducted a tour through Europe to win international support and credibility in 1980 and 1981. In mid-1982, a National Council was formed as a representative political body.Footnote 41

The implementation of Renamo’s objectives on the local level implied a complete reversal of Frelimo’s policies. Attacks were targeted at infrastructure and personnel of the Frelimo state: schools and health posts, party secretaries, and members of the GD. Renamo mobilized the people to abandon communal villages and move back to their area of origin. In the surrounding areas of Renamo bases, the rebels reinstated traditional leaders (calling them mambos in many areas) to mobilize support from the local population. Within Renamo bases, all types of religion could be practiced without punishment.Footnote 42

However, Renamo’s military activities were at odds with its political ideas, which limited its ability to recruit volunteers. Renamo’s first recruits came from the Ndau speakers in Manica and Sofala provinces (Vines Reference Vines1991).Footnote 43 The first Renamo leader Matsangaíssa’s appeal to traditional symbols granted him the support of the local population.Footnote 44 Later, and in other areas, however, Renamo’s increasing use of indiscriminate violence and limited attempts of political education made voluntary recruitment difficult. Renamo’s main strategy became the abduction of young men, including many children (Hanlon Reference Hanlon1984, 229).Footnote 45 Military units often brought the new recruits to bases far away from their homes, so that flight was not an option. Leaders provided limited political training for those that could read and write and extensive military training for others. Renamo’s promises of immediate economic benefits and future positions of power – and in many cases also threat of punishment – convinced the abducted to stay with the armed group (Vines Reference Vines1991, 95).

Renamo’s limited political structure and efforts of mobilization led analysts to conclude that “Renamo was first and foremost a military organization” (Finnegan Reference Finnegan1992, 74). While Renamo’s political organization was relatively weak, its military organization was strong. The organization had a centralized military hierarchy, which was supported by South Africa’s supply of a sophisticated radio network (Vines Reference Vines1991, 82). Afonso Dhlakama was the commander-in-chief, assisted by a fifteen-member military council composed of three chiefs-of-staff for the northern, central, and southern zones, ten provincial commanders, and Dhlakama’s personal staff. Provinces were subdivided into two to three regional commands. One regional command consisted of a brigade, which consisted of several battalions (about 250 men), companies (100–150 men), platoons (30 men), and sections (10 men).Footnote 46

The construction of Renamo bases reflected the group’s centralized military hierarchy. Casa Banana in the Gorongosa district of Sofala province was Renamo’s headquarters until the Zimbabwean recapture of the base on August 28, 1985. Bases were situated in deep forests close to a river for water supply, and huts were dispersed under trees. Many control posts limited access to the center of the base where the main commander stayed. There was a clear separation between Renamo soldiers and the population. The civilian population did not have access to the actual base, but lived in concentric circles around it, thus serving as a disguise for the base and as a “human shield” (Vines Reference Vines1991, 91; Geffray Reference Geffray1990).Footnote 47 In these areas, the population was closely controlled by the locally recruited police force, the mujeeba, that was armed with machetes and knives. The mujeeba worked closely together with mambos to collect food and intelligence for the main base, and at times also went on missions with the armed force (Gersony Reference Gersony1988, 24; Vines Reference Vines1991, 92–93).

The areas in which Renamo established military bases were part of the organization’s “control zones.” Control zones were one of three strategic areas that Gersony (Reference Gersony1988) identified in a study of the refugee situation and Renamo’s human rights violations during the war.Footnote 48 Gersony identified the following strategic areas: tax zones, control zones, and destruction zones. Tax zones were areas in which Renamo soldiers collected food contributions from the population and abducted women to rape them. Control zones were areas in which the population was involved in food production for Renamo soldiers and assisted in the transport of supplies to the bases. In tax and control zones, Renamo did not – or only in a very limited manner – supply any services in exchange for food, goods, and services received. Destruction zones included villages that experienced frequent Renamo attacks until they were completely destroyed and their residents had fled.Footnote 49

Renamo thus established relations with the population that were largely characterized by the – calculated – use of force. Abductions, mutilations, and executions were widespread in destruction zones and used for punishment in tax and control zones (Gersony Reference Gersony1988). Frelimo and some reporters characterized Renamo as “armed bandits,” implying the arbitrary, unpolitical nature of their violence. However, Renamo’s use of violence had a clear strategic goal. Renamo sought to communicate the group’s willingness to dominate by “spreading fear” and demonstrating its “power to hurt” (Wilson Reference Wilson1992, 533; Hultman Reference Hultman2009). Renamo’s use of violence had “ritualistic elements which the perpetrators – who in such circumstances see themselves as some kind of brotherhood socially discrete from the victims – believe provides or imputes value or power into the activity” (Wilson Reference Wilson1992, 531). Violence was always witnessed and “survivors released to tell the horrific tale” (Wilson Reference Wilson1992, 532–33). This strategy cemented Renamo’s control (Wilson Reference Wilson1992, 537).

However, many commentators have remarked that the character and purpose of violence varied substantially across Mozambique. Some early analyses of the war emphasized that there was a difference between violence in the northern and violence in the southern regions. Due to the Frelimo strongholds in the south and Renamo’s difficulty at maintaining occupied areas, rebel activity was reportedly more brutal in that region than in the north, where Renamo could count on voluntary supporters among the peasant population (Roesch Reference Roesch1992, 464; Finnegan Reference Finnegan1992, 72). Areas in which Renamo had attained a certain level of administrative control or areas of total opposition to Renamo did not see high levels of (ritualistic) violence (Wilson Reference Wilson1992, 534).Footnote 50 In the northern regions where Renamo’s control was less precarious, abduction and forced resettlement of the population to the areas’ surrounding bases were more common than atrocities and homicides.

Nevertheless, due to constraints on the availability of information on violent events during the war, there has not been a comprehensive and systematic analysis of patterns of violence across the entire country. Other analysts therefore criticize the neat distinction between the characterization of violence in the northern and southern regions. Morier-Genoud (Reference Morier-Genoud, Cahen, Morier-Genoud and Rosário2018), for example, shows that in the southern province of Inhambane Renamo could benefit from early popular support, as it tapped into preexisting conflicts within and between communities, which presumably shaped the rebels’ perpetration of violence. Cahen (Reference Cahen2019) shows, relying on internal Renamo documents from the central region of Mozambique, that Renamo commanders took great care in treating “their” local population respectfully, even if they did so in an authoritarian manner.

Overall then, Renamo evolved into a well-organized military organization that used violence against civilians strategically to expand its control over the population. In central and northern regions, however, Renamo relied more on abduction and resettlement than on atrocities to intimidate the population. Renamo’s rule based on fear raised the question whether Renamo could ever benefit from genuine popular support, or whether its success would always depend on external resources.

4.2.4 The Relation between External and Domestic Sources of War

Frelimo’s internal conflicts and economic policies after independence and Renamo’s destructive military strategy, limited political goals, and dependence on external resources generated an intense debate on the origins of Renamo’s success among scholars of Southern African politics. In 1989, Gervase Clarence-Smith published a review of recent books on the failure of Frelimo’s socialist project and the consequences for the war in Mozambique. The publication of Clarence-Smith’s article triggered a lively dispute over the size of Renamo’s popular support base.Footnote 51 Clarence-Smith (Reference Clarence-Smith1989) identifies the villagization program as a major source of opposition to Frelimo’s rural policies, which Renamo was able to exploit.

In fierce critiques of Clarence-Smith’s analysis, published in the same journal, two observers contest the notion that there was any popular support for Renamo. Minter (Reference Minter1989), relying on Gersony (Reference Gersony1988), argues that Renamo’s exclusive aim was the forceful extraction of resources. Minter’s (Reference Minter1994) later published book strengthened the case for a destabilization war pursued by Apartheid South Africa without an apparent domestic base within Mozambique.Footnote 52 Fauvet (Reference Fauvet1989) claims that there is no correlation between the number of people living in communal villages in a particular province by late 1980 and the subsequent strength of Renamo in that province. Thus, he concludes, the villagization program cannot explain Renamo success in these areas.

In a more nuanced analysis, Roesch (Reference Roesch1989) concedes that forced resettlement created disaffection with Frelimo, and Renamo was able to mobilize the support of discontented traditional authorities. However, Roesch maintains that “Frelimo’s loss of popular support and the renewed ascendency of traditional authorities would not, by itself, have precipitated the present level of armed conflict” (Roesch Reference Roesch1989, 20). Disenchantment with Renamo’s widespread destruction and violence and an increased system of force put in place by Renamo signifies that Renamo is “not the counter-revolutionary mass that Clarence-Smith’s review might lead one to believe” (Roesch Reference Roesch1989, 21).

In a defense of the argument that domestic factors fueled the war, Cahen (Reference Cahen1989) states that the war transformed itself from a war of aggression into a civil war in the early 1980s. The urban and technocratic character of Frelimo’s policies created dissent that the one-party state had made impossible to voice in a peaceful manner. Cahen acknowledges that without Rhodesian and South African support, opposition to Frelimo would not have expressed itself in the most violent form of resistance – war. However, without Renamo’s popular support, South Africa could not have created the kind of movement it did. Consequently, an end of South African support would not equal an end to the war.

This debate has shaped the historiography of the war in Mozambique in lasting ways.Footnote 53 For instance, it influenced discussions on the correct characterization of the armed conflict as a “civil war” or “war of aggression/destabilization.”Footnote 54 However, as Cahen (Reference Cahen, Braathen, Bøås and Sæther2000, 172) points out, much of the polemic has not been so much about “the nature of the war as with the nature of Renamo.” Thus, he argues, while “peasant revolt” may not be the right label for Renamo, the war could still be called a civil war (Cahen Reference Cahen, Braathen, Bøås and Sæther2000, 173). Whether scholars see the primary origin of the war in external aggression or domestic discontent, they generally agree, however, that domestic conflicts fed into the war.

What then facilitated the continuation of war was more an opposition to the Frelimo government than support for Renamo. The major lesson to be drawn from the evidence presented for the respective arguments is that there was considerable variation in the level of Renamo’s popular support across regions and over time. My argument is thus not about whether internal or external factors were decisive in fueling Renamo violence, but what explains regional variation in the formation and spread of violent actors. Domestic and localized conflicts influenced patterns of support in various areas (Geffray Reference Geffray1990; Lubkemann Reference Lubkemann2005). Internal factors played a larger role after South Africa took over the sponsorship of Renamo and the rebel movement demanded more political autonomy. This regional and temporal variation implies that local support for Renamo did not necessarily reflect “genuine” support for the movement’s agenda, but rather an expression of discontent with Frelimo or with local conflicts that people sought to solve through their participation in Renamo (Roesch Reference Roesch1989; Chichava Reference De Bruin2007; Do Rosário Reference Do Rosário2009; Morier-Genoud Reference Morier-Genoud, Cahen, Morier-Genoud and Rosário2018).

4.3 Frelimo’s Response to Renamo

Although Frelimo had fought a guerrilla war itself during the liberation struggle, the regime was frequently confounded in its response to the threat posed by Renamo. Frelimo realized the seriousness of the threat when it became clear that Apartheid South Africa was providing major support to Renamo. The regime mobilized external support from neighboring countries and internal support from the people for its various state-initiated vigilante groups and militias to supplement the weak army. However, external support and the militarization of society failed in significantly curbing Renamo’s violence.

4.3.1 War against Internal and External Enemies

Efforts to counter the threat posed by Renamo began in earnest in 1981, framed as a response to the aggression by South Africa.Footnote 55 The Mozambican government garnered regional support for an offensive to the north and south of Mozambique,Footnote 56 and Tanzania, Zambia, and Zimbabwe provided military support starting in March 1982 (Robinson Reference Robinson2006, 142).Footnote 57 Renamo escaped southeast through Gaza province to northern Maputo province; Gaza and Maputo became important areas of Renamo activity and clashes with the army in early 1983 (Robinson Reference Robinson2006, 155) (see map in Figure 4.1). However, Renamo also pushed north, reaching Zambézia in 1982 and Nampula in 1983 (Cahen Reference Cahen, Cahen, Morier-Genoud and Do Rosário2018).

Alarmed by increased Renamo activity in early 1983 and its inability to curb the violence, the Mozambican government reached out to South Africa. Frelimo initiated the first of several talks that would lead to the N’komati Accords with South Africa in March 1984.Footnote 58 The main aim of the accord was to end the respective government’s (in-)direct assistance to opposition movements in the other country, though Renamo and the ANC were not directly named in the accord.Footnote 59 Samora Machel also tried to convince many of the western states to grant support to the Mozambican government and deny any support to Renamo. While the talks advanced, both the Mozambican and the South African governments continued their respective military activity. Frelimo had major successes against Renamo in southern Mozambique – particularly in Inhambane and Gaza provinces – in late 1983. South Africa prepared a potential end of support for Renamo and stepped up the delivery of military supplies.Footnote 60

Yet the N’komati Accord did not bring peace. Renamo increased the number of attacks, in particular around Maputo and the border to Malawi in Tete, Nampula, and Niassa provinces (Robinson Reference Robinson2006, 177–78). The war continued in all three Mozambican regions.Footnote 61 While in 1984 and 1985 Renamo activity focused on the south and north, Frelimo’s counterinsurgency campaign prepared a major assault on Renamo’s main bases in Gorongosa in the central region of Sofala province.Footnote 62 In August 1985, Frelimo attacked Renamo headquarters in Gorongosa, with support from Zimbabwean paratroopers.Footnote 63

Frelimo’s offensive in central Mozambique led to a fierce response by Renamo and a subsequent intensification of the war in Zambézia province. In mid-1986, Renamo was on the defensive. Though the rebels had recaptured their main base Casa Banana in February 1986, Zimbabwean troops supporting the Mozambican government retook it a few months later. Frelimo prevailed in Nampula, Manica, Sofala, and the Limpopo valley, and the military put an end to the “virtual siege” of Maputo (Robinson Reference Robinson2006, 213–14, 217). However, support from Malawi and the channeling of South African supplies through Malawi facilitated the start of the Renamo offensive across Zambézia in July and August 1986. When Malawi came under diplomatic pressure from Zambia, Zimbabwe, and Tanzania for its support of Renamo, it expelled Renamo troops, which increased rebel activity in Zambézia province after October 1986 (Munslow Reference Munslow1988, 30).

After President Samora Machel’s death in October 1986, the new president Joaquim Chissano stepped up military pressure on Renamo again and tried to win the war. Machel died in an airplane crash on his return from South Africa on October 19, 1986 under mysterious circumstances (Fauvet and Mosse Reference Fauvet and Mosse2003).Footnote 64 The subsequent government offensive under Chissano’s leadership in Zambézia province in late 1986 and early 1987 and the end of Malawian support for Renamo put the rebels on the defensive.Footnote 65 In the south, Renamo perpetrated the infamous Homoíne massacre in Inhambane province on July 18, 1987, where more than 400 people died during the attack and the subsequent fighting (Finnegan Reference Finnegan1992, 182; Armando Reference Armando2018; Morier-Genoud Reference Morier-Genoud, Cahen, Morier-Genoud and Rosário2018).Footnote 66

In sum, although Frelimo’s response to Renamo looked promising in the short term, government advances were not sustainable. Renamo’s two major offensives – in the Limpopo valley in 1982 and across Zambézia in 1986 – led to Frelimo counteroffensives in central Mozambique in 1985 and Zambézia in late 1986 and 1987. However, the Frelimo army was not able to hold all the towns and localities it recaptured from Renamo. The increased level of atrocities in the south and other Renamo operations in the central and northern regions strengthened Renamo’s position. This led to a military stalemate in 1988; the Mozambican government realized that the war could only be ended by a negotiated settlement.Footnote 67

4.3.2 Challenges to Frelimo’s Counterinsurgency Strategy

In the mid-1980s, it became clear that Frelimo’s campaign against the “enemies of the revolution” and the strategy to delegitimize any opposition in independent Mozambique had failed. The government attempted to minimize Renamo’s and other opposition groups’ threat to domestic stability and denied that internal factors contributed to the unrest (Cahen Reference Cahen, Braathen, Bøås and Sæther2000, 164). It also refused to admit that opposition groups had any support from the population. From the very beginning of armed activity after independence, Frelimo officials referred to the perpetrators as “armed bandits” to downplay their political relevance. In archival documents, government agencies also spoke of “marginals” that were involved in enemy activity.Footnote 68 Frelimo mobilized the whole population to be vigilant about these “marginals” and organized people into state-initiated vigilante groups and militias. When that strategy proved unsuccessful, the army further undermined the government’s stance by engaging in human rights violations such as forced recruitment and the forced resettlement of the population.

Although the Mozambican state military grew out of a guerrilla army that fought the independence war, its response to Renamo’s guerrilla war was surprisingly inept. The military was not prepared for counterinsurgency. In fact, the army achieved most military successes in the mid- to late 1980s with support from foreign forces. Moreover, the party had severe difficulties in controlling the army. For instance, the chief of staff, Colonel-General Mabote, was accused of being involved in an attempted coup against Samora Machel, and thus was expelled from the country in 1986.Footnote 69 Widespread corruption within the army throughout the war contributed to its ineffectiveness (Robinson Reference Robinson2006, chapter 7).Footnote 70

One of the major difficulties proved to be the mobilization and retention of a motivated and capable fighting force. In 1986, for example, intelligence reports stated that soldiers had low morale and low pay, and there was a lack of planning and logistics.Footnote 71 Since 1978, Mozambique had had compulsory military service, but many districts reported that youths dodged the draft due to difficult conditions in the army and the lack of food and supplies.Footnote 72 At the point of the intelligence reports, most soldiers were recruited by force. Soldiers abducted youths on their way to school and brought them to training camps far away from their homes (cf. Schafer Reference Schafer2007, 78–79). This operation was known as operação tira camisa (operation shirt removal): Soldiers forced new recruits to take off their clothes and shaved their heads so that it would be easy to recognize them when they fled.Footnote 73 New recruits were thus treated like prisoners. As one former Frelimo combatant told me, “We were recruited like thieves.”Footnote 74 Notably, many of these recruits were under the age of eighteen, which demonstrates that not only Renamo made use of child soldiers.Footnote 75 Due to limited access to supplies and low morale, soldiers frequently attacked relief convoys and pillaged goods. Some army commandos also provided Renamo with supplies and information (Cabrita Reference Cabrita2000, 259–60).

The government recognized that the military was inadequately prepared for counterinsurgency, but an effort to restructure the army after Samora Machel’s death in 1986 did not bring the expected, lasting change on the battlefield. The party considered the army’s initial training for conventional warfare and its rapid growth prompted by the fast-changing situation on the ground as the main challenges in its response to Renamo. These factors combined to inhibit proper organization, training, and logistics.Footnote 76 The restructuring was supposed to address these shortcomings, and thus in 1987, Chissano replaced most of the provincial commanders and retired 122 officers, mostly veterans from the liberation struggle.Footnote 77

The restructuring did not prevent Renamo from successfully launching its offensives across the central region of Mozambique. This led Frelimo in the late 1980s to increasingly rely on Special Forces, such as the Russian-trained Red Berets (Boina Vermelha).Footnote 78 In 1987–88, the Red Berets, together with 3,000 Tanzanian troops, supported the government’s response to Renamo’s offensive in Zambézia province. By March/April 1989, the government had regained control of all the district towns in Zambézia province.Footnote 79 Tanzanian soldiers remained stationed in the towns to defend them. Renamo combatants withdrew from northern Zambézia to Nampula province, where violence along the national highway subsequently increased.

In addition to relying on Special Forces, Frelimo increasingly delegated security tasks to state-initiated militias, but their involvement in the war did not bring peace but further deteriorated security.

4.3.3 Frelimo’s System of Territorial Defense

A crucial part of the reorganization of the army after 1986 was the creation of a “system of territorial defense and security,” a scheme that gave an important role to state-initiated militias.Footnote 80 This was not an entirely new institution, as it “dates back to a militia that linked peasants and guerrilla fighters in the war for independence” (Pachter Reference Pachter1982, 608).Footnote 81 FRELIMO built on citizen involvement in community patrols and intelligence gathering in its liberated zones before independence, and across Mozambique after. People were organized into vigilante groups (grupos vigilantes) and popular militias (milícias populares) – state-initiated militias that had the task to control the movement of the population. The government signaled its commitment to continuing its independence war strategies by appointing provincial military commanders – veterans from the liberation struggle – to provinces where they were from in March 1982.

In its initial conception, the idea of organizing people into militias was foremost a political and ideological instrument of organizing the masses in support of the state, first in light of internal and later in light of external threats. Warning of “internal enemies,” President Samora Machel emphasized the importance of delegating security tasks to the population to safeguard the revolution right after independence (Frelimo 1978, 58). After South Africa took over the role of Renamo’s main sponsor, Frelimo expanded the militia and vigilante programs to address threats from external enemies – South Africa supporting Renamo (Hanlon Reference Hanlon1984, 232). In 1981, President Machel sharpened his rhetoric and called the people to arms to defend the sovereignty of the young nation: “Sharpen your hoes and picks to break the heads of Boers. Prepare yourselves with all types of arms so that no aggressor leaves our country alive.”Footnote 82 The popular militias thus took on the task of military defense, primarily in those provinces and districts close to the Rhodesian/Zimbabwean border (Alexander Reference Ahram1997, 4). The new statute and program of the party Frelimo approved by the party’s Fourth Congress in 1984 formalized this approach and defined the task of the popular militias as supporting the defense and security organs in the defense of territorial integrity against the “internal enemy” and against aggressions by “imperialism’s counter-revolutionary forces.” It also assigns militias the task to ensure public order more generally.Footnote 83

As a former guerilla movement, Frelimo recognized the importance of the local population for supporting rebels and thus saw in the militia and vigilante program a way to ensure the loyalty of the population. The militarization of society culminated in the late 1980s, when the minister of defense at the time, Alberto Chipande, “argued that the war effort was not merely the FPLM’s [army] responsibility, but that all sectors of economic life, and Mozambican citizens in general should play a full role in defence.”Footnote 84 The minister recalled that during the independence struggle everyone in liberated zones contributed to the victory over Portuguese forces: “‘Today as well we must give a popular character to our war,’ he urged.”Footnote 85 These remarks demonstrate that the Mozambican government increasingly saw the war with Renamo as one over people.

Beyond these political-ideological considerations, the training of locals to support the limited number of armed forces served three major, practical purposes: the collection of intelligence, the multiplication of armed forces, and the expansion of control to rural areas. First, the war against the Renamo guerrilla movement necessitated detailed intelligence and close control of the population, which the army and local administration were unable to ensure alone. Organizing community residents with access to local information and a motivation to protect their own neighborhoods seemed a promising way to answer the challenge posed by Renamo (Finnegan Reference Finnegan1992, 211). Moreover, in some regions, militias supplemented or even replaced the military. The dire situation of the Frelimo military made army recruitment difficult. Logistical shortcomings caused the army to be severely undersupplied, forcing troops to either grow their own crops or live off the surrounding population.Footnote 86 Lastly, militias extended Frelimo’s meagre military presence to the countryside. The state army concentrated on the district towns and on strategic localities, but most areas outside of the district towns had little, if any, military presence.

Contrary to these expectations, the state-initiated militias did not solve the government’s military challenges. The local administration faced major challenges in mobilizing community residents for the state-initiated militias. In the districts under study for this book, militias rarely received uniforms and weapons, and they were typically not paid. Desertion rates were high, the government had to resort to forced recruitment, and the population often complained about militias’ ill-treatment of the people they were supposed to protect (Finnegan Reference Finnegan1992; Alexander Reference Ahram1997). The decentralization of security became a major problem as the increased supply of weapons to the population contributed to banditry and warlordism (Finnegan Reference Finnegan1992, 232).Footnote 87 In 1991, the Minister of the Interior recognized that the distribution of weapons to the population had not been well controlled, and thus many people were in possession of illegal weapons.Footnote 88

As the war became a war over people, both Renamo and Frelimo sought to control the population by forcibly resettling people into areas under their control. Together with the army, state-initiated militias were involved in the forced resettlement of the population, which further diminished people’s trust in them. With the help of these militias, Frelimo “recuperated” the people in Renamo-held territories and brought them to government-held areas. These people were settled in accommodation centers, named after people’s locale of origin (cf. Igreja Reference Igreja2007, 132) and organized in a manner similar to communal villages. The centers had a central party structure and all activities were closely controlled by state-initiated militias. Again, this strategy was taken from Frelimo’s playbook of the independence struggle. Thaler (Reference Thaler2012, 552) finds that the most common type of Frelimo violence against civilians during the war of liberation was abduction to assemble people away from Portuguese control and effectively indoctrinate them. Frelimo’s strategy of population resettlement was to adopt the Portuguese counterinsurgent strategy of building aldeamentos – strategic resettlement villages – to concentrate and closely monitor the population. Forced population resettlement became particularly important for the Frelimo government when the peace process advanced in the late 1980s, as peace implied the holding of multiparty elections that Frelimo needed to win.Footnote 89

However, the introduction of the territorial defense system in 1986–87 only brought temporary success. Renamo consolidated its elite forces in October 1988. The Tanzanian troops that supported the government withdrew in December 1988, which made it difficult for the Frelimo army to hold the newly recaptured towns. The government also faced new challenges in the south. In early 1988, the areas the hardest hit were Gaza and Maputo. Renamo’s apparent goal was to cut off Maputo from the hinterland and “create a reputation for Dhlakama as ‘Savimbi-style’ personality with an organized force,”Footnote 90 referring to Angola’s rebel leader Jonas Savimbi.Footnote 91

In sum, although Frelimo attempted to learn from its own experiences as a guerrilla movement and built on the close control of the population, its counterinsurgency strategy remained inadequate and poorly executed. The forced recruitment of army soldiers and state-initiated militias together with the forced resettlement of the population into communal villages alienated the population. Territorial gains remained temporary, as Renamo regularly regrouped and staged successful counteroffensives. By 1988, the south was under severe pressure. Frelimo considered the war as having reached a military stalemate and seemed to give up on finding a military solution to the conflict. Attempts at creating economic incentives to end the war through the adoption, in January 1987, of an IMF-sponsored structural adjustment program (Economic Rehabilitation Program/Programa de Restruturação Econômica, PRE) did not solve, but rather added to, Frelimo’s problems.

4.4 Community Responses to the War

The population was disenchanted with Frelimo’s response to Renamo. The failure of Frelimo’s counterinsurgency strategy and the lack of military support in the rural areas provoked community responses to the war that resulted in many different armed and unarmed forms of defense.

4.4.1 Sources of Resistance

As is usually the case in irregular civil wars, the population was the main supporter of the war, providing food, supplies, and intelligence to the armed organizations on either side, and was thus also the main target for intimidation, exploitation, and violence. Recognizing the population as a crucial resource for which they competed, neither side exclusively relied on political indoctrination to convince civilians to support them. They also forcibly recruited combatants and civilian supporters, perpetrated indiscriminate and collective violence against civilians, and forcibly resettled community residents into areas under their control in order to ensure people’s loyalty.

Many people came to believe that the war itself was about the population (Cahen, Morier-Genoud, and Do Rosário Reference Cahen, Morier-Genoud, Do Rosário, Cahen, Morier-Genoud and Do Rosário2018b).Footnote 92 Civilians frequently shifted identities and opted for supporting the side that provided protection at a particular moment (Bertelsen Reference Bertelsen, Kapferer and Bertelsen2009, 222; Legrand Reference Legrand1993). As a consequence, people found themselves between two forces. Due to quickly shifting loyalties and the risk that civilians could serve as informers to the other side, both Renamo and Frelimo considered control over people as a major objective of their operations. As one Renamo combatant I interviewed put it: “The combat was about the people. To have the majority of the population meant to have more security.”Footnote 93 The goal to control people took on a punitive character and translated into the control of “bodies through herding, coercing, or kidnapping people” (Bertelsen Reference Bertelsen, Kapferer and Bertelsen2009, 222).

Community residents I spoke with saw themselves as the war’s main victims who lacked agency. They cited a well-known Swahili and Mozambican proverb, “When two elephants fight, it is the grass that suffers,” comparing themselves to the grass that suffers beneath fighting elephants.Footnote 94 In a similar way, the Mozambican writer Mia Couto, in his novel Terra Sonâmbula (Sleepwalking Land), characterized the civilian population’s situation during the war as one in which the people were the ground for one side, and the carpet for the other: “My son, the bandits’ job is to kill. The soldiers’ job is to avoid dying. For one side we’re the ground, for the other we’re the carpet” (Couto Reference Couto1996, 23). This victim narrative represented civilians as marginalized and without agency. In my conversations, I frequently heard statements like “war is war” or “soldier is soldier,” which expressed passive acceptance of the ineluctable violent rules of war.Footnote 95 Civilians saw themselves as defenseless spectators, fleeing from their homes into the bush or the mountains in case of an attack: “We were like the children of the household, we only observed what happened.”Footnote 96 Respondents felt they were helpless in the face of violence.

From this victim narrative emerged a second narrative of the need to transform passivity into activity. When recalling the war situation of the mid- to late 1980s, community residents explained that they were getting “tired of war” and were looking for ways to end their suffering.Footnote 97 They developed both unarmed and armed strategies to defend themselves against what they felt to be an arbitrary war, and by doing so built on preexisting social conventions. In a society in which traditional religion remained strong despite Frelimo’s efforts to eradicate all “obscure” beliefs, traditional healers played a large part in these efforts and initiated a range of protective strategies for both Renamo and Frelimo forces, as well as the civilian population.

Communities’ reliance on social conventions needs to be understood in the context of the spiritual dimension of the war. In his fascinating study of “cults and counter-cults of violence,” Wilson (Reference Wilson1992) analyzes how Renamo enlisted the help of spirit mediums in its bases, creating a “myth of invincibility” that was later countered by the community-initiated militia Naparama. References to the spirit world helped Renamo connect to peasants by making its use of power “meaningful,” however horrendous its violence was (Wilson Reference Wilson1992, 535). Several important Renamo commanders in Zambézia province were famous for their spiritual powers, and thus shaped events on the battlefield accordingly. Renamo military commanders even declared a “war of the spirits,” which represented the fight against Frelimo’s repression of all forms of religion (Roesch Reference Roesch1992).

However, “the ‘war of the spirits’ was later to turn against Renamo” (Wilson Reference Wilson1992, 548), and Renamo’s advantage in the realm of spiritual power came to an end in the mid- to late 1980s. Traditional leaders and healers allied with Renamo at first because, as previously mentioned, Frelimo had prohibited the activity of traditional healers right after independence. However, people who initially supported Renamo became alienated by their violent tactics (Wilson Reference Wilson1992, 548).Footnote 98 In order to protect themselves from the rebels’ spiritual power, community residents engaged in similar strategies to counter Renamo’s “cult of violence.” At the same time, Frelimo adjusted its stance toward tradition, religion, and culture and began tolerating – but not endorsing – traditional healers’ activities, hence the proliferation of traditional healers that offered their assistance to communities and individuals within the military.Footnote 99

The Naparama militia belongs to the community initiatives that made use of such conventions for developing armed strategies of protection.

4.4.2 The Rise of the NaparamaFootnote 100

In the context of the “war over people” and the spiritual dimension of war, the Naparama, an armed movement led by the traditional healer Manuel António in Zambézia and other healers and community leaders in Nampula, dramatically influenced the dynamics of war in these provinces. No other self-defense mechanisms that had emerged before resulted in anything like the rapid social and military successes Naparama achieved. The first appearance of Naparama was in the border region between Nampula and Zambézia provinces, but it quickly spread across the region. The movement gained control over two-thirds of the northern territory within a short amount of time, becoming “one of the most important military and political factors in contemporary Mozambique” (Wilson Reference Wilson1992, 561).Footnote 101

Due to the militia’s legendary character, which built on the fierce reputation of its leader and the seemingly “magical” successes against Renamo, it is difficult to ascertain how large the group actually was. News reports from the time estimate that the number of Naparama recruits jumped from 400 in July 1990 to 20,000 in September 1991.Footnote 102 António himself claimed to have about 14,000 fighters in May 1991.Footnote 103 After the war, in 1994, news reports spoke of 9,000 Naparama who had assembled in the district of Nicoadala in Zambézia province.Footnote 104 However, the journalist Gil Lauriciano, who covered the war in Zambézia extensively, estimates that the group did not have more than 2,000 members.Footnote 105 My interviews with former Naparama members indicate that many districts had about 200 Naparama, which only included those in the main district town. As a result, I estimate the size to be about 4,000–6,000 members across both provinces, Zambézia and Nampula.Footnote 106 The spiritual roots of Naparama lay in the belief that a potion prepared with roots and leaves would make people, through vaccination, immune to bullets. Naparama’s combatants only fought with weapons of cold steel – armas brancas (white weapons) – spears, arrows, machetes, and knives. Their behavior was codified with a strict set of rules that, when respected, was believed to maintain the vaccine’s effectiveness. The rules referred to the militia members’ behavior at home, such as prohibiting certain foods, and to their behavior on the battlefield, such as the rule not to retreat. Deaths during battle were usually attributed to violations of these rules.

Building on the strength it could generate as a “traditional” fighting force, Naparama put major pressure on Renamo in Nampula and Zambézia provinces. In 1988 and 1989, it became clear that the Frelimo government had difficulties holding the areas liberated during the military offensive from late 1986 onward. Naparama filled an important gap, helping to defend camps for the displaced, as well as district towns and surrounding areas, and liberating more areas from Renamo control. This put Renamo under pressure during the advancing peace negotiations. As a consequence of the Naparama offensive in 1990, Dhlakama refused to send his negotiation team to the third round of meetings in September 1990.Footnote 107 During Renamo’s counteroffensive in 1991, the main goal was to recapture lost territory before signing a peace agreement in the politically important province of Zambézia.Footnote 108 This new Renamo offensive led to the killing of Zambézia’s Naparama leader, Manuel António, in late 1991.