Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- Notes on Contributors

- Introduction

- The Curious Production and Reconstruction of Oxford, Bodleian Library, Junius 85 and 86

- ‘Through a glass darkly’, or, Rethinking Medieval Materiality: A Tale of Carpets, Screens and Parchment

- Distortion, Ideology, Time: Proletarian Aesthetics in the Work of Lionel Britton

- Shakespeare and Korea: Mutual Remappings

- Dictionary Distortions

- Where Do Indigenous Origin Stories and Empowered Objects Fit into a Literary History of the American Continent?

- Distortion in Textual Object Facsimile Production: A Liability or an Asset?

- The Uncanny Reformation: Revenant Texts and Distorted Time in Henrician England

- The Presence of the Book

- Index

Introduction

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 24 August 2019

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- Notes on Contributors

- Introduction

- The Curious Production and Reconstruction of Oxford, Bodleian Library, Junius 85 and 86

- ‘Through a glass darkly’, or, Rethinking Medieval Materiality: A Tale of Carpets, Screens and Parchment

- Distortion, Ideology, Time: Proletarian Aesthetics in the Work of Lionel Britton

- Shakespeare and Korea: Mutual Remappings

- Dictionary Distortions

- Where Do Indigenous Origin Stories and Empowered Objects Fit into a Literary History of the American Continent?

- Distortion in Textual Object Facsimile Production: A Liability or an Asset?

- The Uncanny Reformation: Revenant Texts and Distorted Time in Henrician England

- The Presence of the Book

- Index

Summary

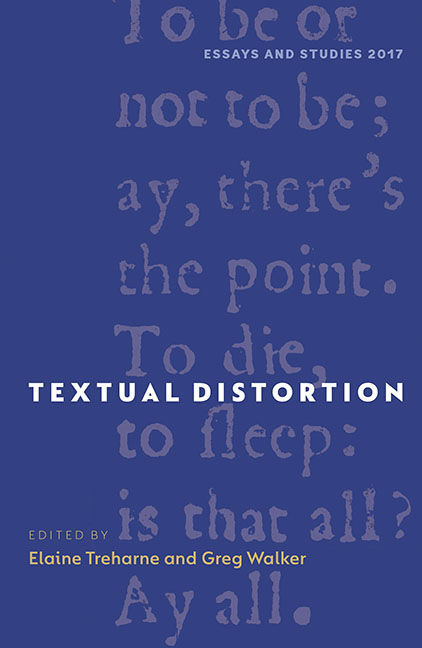

‘The most dangerous untruths are truths slightly distorted’

‘Distortion’ is nearly always understood as negative: it can be defined as perversion, unnoticed alteration, impairment, caricature, twisting, corruption, misrepresentation, deviation. Unlike its close neighbour, ‘disruption’, currently enjoying a makeover in British government-speak as a newly positive term (in such collocations as ‘disruptive technologies’ and ‘disruptive industries’), it remains resolutely associated with the undesirable, the lost or the deceptive. The process of distortion is generally seen to create a form of the original (factual, true, authentic, real) that is not transubstantive as such, but deformed: warped, misshapen, skewed, shrunken, amplified or simulated. Even in acoustics or music, the notion of distortion, however aesthetically pleasing in itself, most often connotes loss of purity or clarity of signal. And yet, it might equally be said that only through distortion can one find the presence of the original. Indeed, in literary and historical studies, one might argue that all textual transmission is inevitably distorted – either through mediation, translation, appropriation, colonisation, canonisation and authorisation of an elite corpus or authentic version, digitisation, remediation or, more obviously negatively, through misunderstanding, lack of contextualisation, deliberate falsification or pretence.

In the Collegium held at Stanford University in 2015, at which some earlier forms of these essays were presented (Cayley, Ogilvie, Powell, Scorcioni, Walker), the three-day discussion ranged from core issues of space, place, time and context in the production of literary and artefactual meaning, to the archive and its necessary interpretation – whether through sorting and cataloguing or editing, retrieval and display. In tussling with the term and its implications, we returned frequently to the concept of the undistorted and what it might imply, whether in theory or practice. An antonym of ‘distortion’ seems always to be the search for the authentic, the original, the true, as if that might exist textually. Yet, alongside this inbuilt distrust of the text or artefact as a bearer of undistorted meaning, there is an equally evident suspicion of the oral, and of sound or speech – with their evanescence and ephemerality, even when recorded (as is shown brilliantly in Powell's essay).

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Textual Distortion , pp. 1 - 5Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2017