I.1 The Meaning of Tense-Switching

If we ask why tense, aspect and modality have been such fondly pursued objects of research by linguists in the past half century (Klein [Reference Klein1994] noted it had been said before that it had been said before that it is impossible to read all the relevant literature, and the expansion only seems to be accelerating), the appealing response may well be worth taking seriously: that these matters in some way touch at the heart of human experience and that through studying them we may ultimately gain greater insights into our own nature. At the same time, the linguist should be sobered by the realisation that, as Evans (Reference Evans2013: 4) puts it, ‘[time] is one of the most, if not the most, challenging domain of enquiry in terms of understanding the relation between language, perceptual experience, conceptual representation and meaning’.

This book is a study in the semantics and pragmatics of tense-switching in Classical Greek (and beyond) from a cognitive perspective. Tense-switching is the use of different tenses to refer to the same temporal domain. In particular, I will be concerned with the alternation between the past and present tense in references to the past, as illustrated in the following example:

Lennox: Sent he to Macduff?

Lord: He did, and with an absolute ‘Sir, not I,’

the cloudy messenger turns me his back,

and hums, as who should say ‘You’ll rue the time

that clogs me with this answer.’Footnote 1

This use of the present tense to refer to past events (turns, hums) is one of the most obvious paradoxes in language.Footnote 2 It seems to imply a semantic construal in which, contrary to ordinary experience, the gap between the past and the present is bridged somehow. If this assumption is correct (and it has often been challenged; see Section I.2.1), an investigation into the dynamics of tense-switching promises to reveal interesting aspects of linguistic meaning construal and ultimately raises questions about how this, in turn, relates to our non-linguistic conceptualisation of reality.

I.1.1 Cognitive Linguistics, Deixis and Viewpoint

One of the most important general insights promoted by cognitively oriented linguists has been that, as Sweetser and Fauconnier (Reference Sweetser, Fauconnier, Fauconnier and Sweetser1996: 21) put it, ‘[n]atural language has a striking potential for making rich and extensive meaning available on the basis of very little overt linguistic structure’. For example, consider the utterance There is a house every now and then through the valley (Langacker [Reference Langacker2008: 531–5]). Housing density is here construed in terms of time (now and then) rather than space, and of motion (through) rather than staticity. The resulting semantic ‘incoherence’ is only superficial. It seems intuitively plausible that we can meaningfully process this utterance by supplying a conceptual scenario in which we imagine ourselves to be travelling through the valley – even if there is no overt reference to a person engaged in this activity. As a case study in cognitive semantics, this book aims to illustrate the effectiveness of assuming such covert conceptual scenarios in order to explain apparent linguistic discrepancies – in this case, the use of the present tense to refer to past events.

The issue of tense-switching is part of a broader discussion concerning phenomena pertaining to deixis and viewpoint, which has surged in cognitive linguistics recently (see, e.g., Dancygier and Sweetser [Reference Dancygier and Sweetser2012]; Sweetser [Reference Sweetser, Borkent, Dancygier and Hinnell2013]; Dancygier et al. [Reference Dancygier, Wei-Lun and Verhagen2016]; van Krieken et al. [2019]). A main thread in these investigations is the analysis of multiple viewpoint constructions, both in language and in gesture. A multiple viewpoint construction is in effect when different components of a single utterance are grounded in different viewpoints. An example is the so-called ‘past + now construction’ (Nikiforidou [Reference Nikiforidou2010], [2012]), as in the following instance:

And now Tom for the first time saw his future school-fellows in a body.

The paradoxical juxtaposition of the past tense form saw and the proximal temporal adverb now can be unpacked by assigning the use of the past tense to the viewpoint of the narrator and the use of the adverb now to the displaced consciousness of the protagonist, Tom.

Multiple viewpoint constructions, however, constitute only one part of the more general phenomenon of complex viewing arrangements (e.g., Langacker [2011]). In the default viewing arrangement, an utterance is anchored in a single viewpoint and designates a single instantiation of an object of conceptualisation. The complexity of this arrangement can be increased either by multiplying viewpoints, as in (2) under the analysis given there, or by multiplying instantiations of the same object of conceptualisation. This occurs when the distinction between an actual object and a representation of that object is blurred (see also Section I.3). Consider the following example:

He visits with King Duncan, and they plan to dine together at Inverness, Macbeth’s castle, that night.

Here the use of the present tense ostensibly clashes with the distal expression that night. The resolution to this paradox must be different, I believe, from that in the case of (2). There is no particular reason to assume that the present tense here is anchored in a displaced viewpoint, as if we are present as eyewitnesses on the scene. Rather, the use of the present tense depends on the idea that the designated events as represented in the play are always presently accessible through the medium of the text of the play, as well as through regularly staged performances (compare Langacker [Reference Langacker, Patard and Brisard2011] on such ‘scripted’ usages of the present tense). The distal expression that night, on the other hand, signals that the actual instantiation of the designated event was on a particular day that is different from the present day of the writer of the summary (whether the event really occurred or not is linguistically irrelevant). The expression tonight would be infelicitous in this context, as it would mean that Duncan and Macbeth plan to dine the night following upon the writing of the summary.

The main theoretical contribution of this study to the debate on deixis and viewpoint in cognitive linguistics lies in the formulation of a principled distinction between these two complex viewing arrangements – the multiple viewpoint scenario and the multiple instantiation scenario, or ‘representation scenario’ – and in a thorough exploration of the conceptual structure of the latter type. While the multiple viewpoint scenario has received the lion’s share of attention so far, I argue that the representation scenario generally has a greater explanatory value with respect to the phenomenon of tense-switching and also sheds a different light on other deictic paradoxes (such as the ‘past + now construction’).

I.1.2 Tense and the Experience of Time

A deeper question concerning tense usage is how the grammatical construal of temporality relates to our psychological experience. One of the central tenets of cognitive linguistics is that our capacity for language is not a separate module but is grounded in other cognitive systems and faculties, such as perception, memory and categorisation (e.g., Langacker [Reference Langacker2008: 8]). Grammatical categories depend on these systems and faculties for imposing a certain construal on the basic conceptual content that is described. For example, Langacker (Reference Langacker2008: 105) argues that the noun category serves to construe the conceptual content conveyed by its lexical meaning as a thing, that is, a product of grouping or reification. Reification, in turn, is the ‘capacity to manipulate a group as a unitary entity for higher-order cognitive purposes’. A verb, on the other hand, construes the conveyed conceptual content as a process, which involves the cognitive operation of sequential scanning.

How does this pertain to tense? Evans (Reference Evans2013: 57–61, 81–2) summarises the evidence for the neurological basis for our deictic system of temporal reference, with the basic distinction being between ‘present’ and ‘non-present’. The ‘present’ is that which we experience in the perceptual moment, a fleeting ‘now’ that is refreshed every two or three seconds. The brain regions involved in remembering the past and thinking about the future are interrelated and distinct from those involved in the construction of the perceptual moment (Evans [Reference Evans2013: 60]). Thus, the temporal construal imposed by the present and past tenses on the designated conceptual content is grounded in pre-linguistic cognitive systems.

Now, the question with respect to tense-switching is the following: does the linguistic construal of a past event as part of the present tell us something about the speaker’s psychological experience of that event? That is, does the speaker, when using the present instead of the preterite, actually fail to properly distinguish between experiencing the immediate reality of the perceptual moment and remembering what is past?

There is some evidence pointing in this direction from the study of autobiographical narratives of trauma. Hellawell and Brewin (Reference Hellawell and Brewin2004) had patients diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder write detailed narratives of their trauma. Afterwards, these patients identified which sections had been written in ordinary memory periods and which in flashback periods (intrusive memories that are felt as current experience: O’Kearney and Perrott [Reference O’Kearney and Perrott2006: 82]). The results showed that narrators described events in more detail, and used the present tense more often, in flashback periods. Similarly, Manne (2002) found that in parents’ stories about their children who survived cancer, use of the past tense was associated with fewer traumatic stress symptoms (see O’Kearney and Perrott [Reference O’Kearney and Perrott2006: 88] for some other references). The correlation between the use of the present tense to refer to the past and vividness of memory is not confined to patients suffering from traumatic experiences. In a study comparing patients who had their memory impaired by unilateral temporal lobe excision or epilepsy to a healthy control group, Park et al. (Reference Park, St-Laurent, McAndrews and Moscovitch2011) found that the people in the latter group used the narrative present more often and that the use of the narrative present ‘correlated positively with other measures of recollection, such as the total number of perceptual details contained in a narrative’ (Park et al. [Reference Park, St-Laurent, McAndrews and Moscovitch2011: abstract]).

It would be extremely naïve, however, to assume a one-to-one correlation between tense usage and psychological experience. While the evidence suggests that vividness of recollection prompts the use of the present tense to refer to the past in the context of autobiographical narrative, this does not mean that tense-switching is always conditioned in this way. As I will show with many examples throughout this study, the present tense is often used to refer to the past in contexts devoid of symptoms of a particular vividness of recollection. In such cases, the ‘presentness’ denoted by the present tense becomes a more abstract notion than our understanding of what is actually occurring in the current perceptual moment.

This general point may be illustrated with a related deictic grammatical category: that of demonstratives. As Kemmerer (Reference Kemmerer1999) points out, many languages have a bipartite division between ‘proximal’ and ‘distal’ in their demonstrative systems (this versus that). There seems to be a corresponding neurological distinction between what we experience as ‘near’ or part of our ‘peripersonal space’ (roughly, what is within arm’s reach) and ‘far’ or part of ‘extrapersonal space’. However, Kemmerer (1999: abstract) argues that ‘the distinction between proximal and distal demonstratives … does not correspond to an independently established distinction between near and far space in the visual system but is instead based on language-internal factors’. For one thing, many languages have demonstrative systems with more than two categories of remoteness. Moreover, it is evident that in language use the proximal-distal distinction often does not reflect actual spatial distance (Kemmerer [Reference Kemmerer1999: 51–5]). While the pre-linguistic distinction between the near and the far may have been the initial anchor for the distinction between proximal and distal demonstratives, the linguistic notions of ‘proximal’ and ‘distal’ are often more abstract in character and require complex inferences by the addressee to be properly interpreted.

In analogous fashion, the past and present tenses, in their prototypical uses, can be related to the distinction between what is immediately experienced in the perceptual moment and what is retrieved through recollection. Some ‘switched’ uses of the present tense can be accounted for in terms of a change in ordinary experience, where recollection feels like re-experiencing. In other cases, the ‘presence’ of a past event is related to more abstract notions such as discourse status or cultural familiarity. I will have more to say about these different implications of tense-switching in Section I.2.2.

I.2 Questions and Aims

Tense-switching has been a hot topic among linguists and narratologists in the past decades, and research into the phenomenon spans wide areas of space, time and genre: from European languages such as (American) English (e.g., Wolfson [Reference Wolfson1978]; Schiffrin [Reference Schiffrin1981] etc.; Levey [Reference Levey2006]), French (Fleischman [Reference Fleischman1990]; Mellet [Reference Mellet, Vogeleer, Borillo, Vetters and Vuillaume1998]; Carruthers [Reference Carruthers2005]), Spanish (Silva-Corvalan [1983]; van Ess-Dykema [1984]; Bonilla [Reference Bonilla2011]) and modern Greek (Thoma [Reference Thoma2011]), to such unrelated languages as Japanese (Iwasaki [Reference Iwasaki1993: ch. 3]), Wolof (Perrino [Reference Perrino2007]) and Kala Lagaw Ya (Stirling [Reference Stirling2012]); from the Classical Age (Lallot et al. [Reference Lallot and Lallot2011]; Adema [Reference Adema2019]) through the age of the New Testament (Runge and Fresch [2016]) and the Middle Ages (Fleischman [Reference Fleischman1990]) to recent times (Park et al. [Reference Park, St-Laurent, McAndrews and Moscovitch2011]); and from highly literary texts (Fludernik [Reference Fludernik1992]) to fully conversational narrative (Norrick [Reference Norrick2000]), with the space in between filled with, to name a few, performed stories (Fleischman [Reference Fleischman1986]), courtroom speeches (Nijk [Reference Nijk2013a]) and narratives elicited in interviews (Wolfson [Reference Wolfson1978]; Park et al. [Reference Park, St-Laurent, McAndrews and Moscovitch2011]).

It would be gratuitous to state that from such a diversity of investigations no consensus has emerged concerning the semantics and pragmatics of tense-switching. It may, however, be pointed out that most studies have been limited in scope – focusing, for example, on picked text passages or specific verb types, or on statistical correlations between tense usage and certain contextual features – so that the overall picture that emerges from the literature tends to be somewhat fragmented. This study certainly does not set itself the goal of presenting an exhaustive survey of tense-switching in even a single language, but it does aim at a more thoroughly integrated account of the phenomenon. While I focus mainly on Classical Greek, my account is intended as a model for the analysis of tense-switching in other languages as well (see especially Chapter 1).

There are two main aspects in which the present investigation distinguishes itself in terms of its scope. First, my account integrates three levels of linguistic analysis by focusing on the following questions:

(a) How can the use of the present tense to refer to the past be understood in terms of the semantics of the present tense? Is there a conceptual scenario (or are there several) that allow(s) for the construal of past events as being part of the present?

(b) What are the pragmatic functions of the present tense when used to refer to the past, and how are these functions derived from the semantics of the present tense?

(c) How do these pragmatic functions translate into quantifiable usage patterns?

Thus, I move from abstract semantic theorizing all the way down to empirical observation. This approach is inspired by Allan (Reference Allan, Bakker and Wakker2009, 2011), who is the rare exception to the rule that researchers tend to focus mainly on one or two of these levels of analysis. Allan’s studies, however, are limited in scope, and my account of the semantics of the present tense in relation to tense-switching (1), as well as my methodology for quantitative analysis (3), are in some respects substantially different.

Second, my account both acknowledges distinct usages of the present tense to refer to the past and unifies these under a general model. Many researchers focus on one particular usage, most often the familiar ‘vivid’ type that is common in conversational narrative (So I walk over and I say to him etc.). Others acknowledge different usages but fail to explain how exactly they are related. For example, in his Syntax and semantics of the verb in Classical Greek, Rijksbaron (2002: 22) suggests that for some uses of the present tense in narrative ‘the notion of “present” may play a part to the extent that a “pseudo-present” or “pseudo-moment-of-utterance” is created: the narrator plays the role of an eyewitness’ (see Section I.2.1 for this idea of viewpoint displacement). Rijksbaron notes that this does not hold for all uses, which leaves open the question how the pragmatic function of the present tense in those other cases (such as ‘punctuating the narrative’, page 24) is derived from its semantics. An extreme response to the unsatisfactoriness of this state of affairs has been the rejection of a plurality of explanations and the adoption of a monolithic view of the praesens pro praeterito as a grammatical category (Sicking and Stork [Reference Sicking, Stork and Bakker1997: 132]). I will argue that we can in fact make a principled distinction between different usages of the present tense to refer to the past, each with its own specific conceptual scenario, pragmatic functions and conditions of use.

I will now elaborate on these points in more detail while laying out the plan of this book.

I.2.1 The Semantics of Tense-Switching

In Chapter 1, I present a general account of the semantics of the present tense with reference to its use to designate past events. Broadly speaking, there are two views with respect to this issue. Conceptualist accounts depart from the assumption that the present tense serves to construe past events as somehow being cotemporal with the here and now of the speaker and addressees. The opposing view, which may be called ‘functionalist’ or perhaps ‘anti-conceptualist’, rejects this assumption, arguing that the present tense is devoid of time-referential meaning (e.g., Wolfson [Reference Wolfson1978 etc.]; Fleischman [Reference Fleischman1990]). I begin by addressing the problems with this alternative view, thereby putting the conceptualist assumption on firm footing.

Within the conceptualist paradigm, it is most commonly argued that the use of the present tense to designate past events depends on a conceptual scenario whereby the speaker mentally displaces their present viewpoint to the past, so as to pretend to be an eyewitness to the actual past events. As I will argue, however, the present tense is often used to refer to the past in ways that contradict the idea of a displaced viewpoint. The solution to this problem lies in the recognition of a second, alternative conceptual scenario that may bridge the gap between the near and the far (see Bühler [Reference Bühler1990 {1934}: 154–7] on spatial deixis). In this alternative scenario, the past events are mentally transported into the present in the form of a representation (compare Vuillaume [Reference Vuillaume1990: especially 35]; Gosselin [Reference Gosselin2000]; Langacker [Reference Langacker, Patard and Brisard2011]).Footnote 3 This may be realised in different ways: we can conceive of past events as occurring in the present in the form of a play, an improvised performance, video footage or even through the medium of the speaker’s discourse (the past events are ‘present’ in the sense that they are presently being discussed).

I present four case studies from different languages and genres to illustrate the explanatory value of these distinct conceptual scenarios for specific usages of the present tense to designate past events. I argue that the displacement scenario seems to be confined to a particularly artificial style of narrative presentation, while the representation scenario is able to account for tense-switching more generally. From this point onwards I use the term ‘present for preterite’ to designate the use of the present tense that corresponds to the latter scenario.

I.2.2 Three Usages in Classical Greek

Having established a general theoretical account of tense-switching, I turn to the Classical Greek corpus in Chapters 2–4. Each chapter is devoted to a particular usage of the present for preterite (the distinction between the usages identified here was anticipated by von Fritz [1949]). I argue that each usage is associated with a specific conceptual scenario: while each involves the concept of a representation as a medium between the past events and the present circumstances, the nature of this representation differs from one usage to another. This also entails that the present for preterite carries different pragmatic implications in each case, which translate into different usage patterns.

The main variable behind the tripartite division of present for preterite usages proposed in this study is that of narrativity, which, for my purposes, may be understood in terms of narrative experientiality. In Fludernik’s (Reference Fludernik1996, Reference Fludernik and Herman2003) sense, narrative experientiality is the degree to which the processing of a representation of past events in discourse is analogous to the processing of actual experience.Footnote 4 I distinguish three fields on this continuum, each with a corresponding usage of the present for preterite. However, I will take care to emphasise throughout that the boundaries between these categories are fluid and that the different interpretations of the function of the present for preterite are not always mutually exclusive.

My corpus consists of the main texts of the Classical period (fifth and fourth centuries bc) in which tense-switching occurs. I discuss material from the historians Thucydides, Herodotus and Xenophon; from the canonical orators Aeschines, Andocides, Antiphon, Demosthenes, Dinarchus, Hyperides, Isaeus, Isocrates, Lycurgus and Lysias; from the dramatists Aeschylus, Aristophanes, Euripides, Sophocles and Menander and finally, I use some examples from Plato. The quantitative analyses presented in Chapters 2 and 3 are confined to selected portions of this corpus.

I.2.2.1 Scenic Narrative and the Mimetic Present

Chapter 2 begins with scenic narrative, which is mainly characterised by a close relationship between discourse time and story time.Footnote 5 That is, the time it takes for the discourse to progress is close to the time it took for events represented by the discourse to actually occur; there is thus a high degree of iconicity between narrative experience and actual experience. In such contexts, we find the mimetic use of the present for preterite. (For the present tense and narrative mimesis compare, e.g., Wolfson [Reference Wolfson1978 etc.]; Fleischman [Reference Fleischman1990]; Kroon [Reference Kroon, Sawicki and Shalev2002]; Allan [Reference Allan, Bakker and Wakker2009 etc.].) An example is the following:

I argue that the mimetic present serves to highlight the present accessibility of the designated past events through the medium of a simulation or re-enactment, which is constituted by the narrative performance. I will try to corroborate this idea with statistical correlations between present for preterite usage and aspects of narrative experientiality. I break this down into three categories: the nature of the conveyed conceptual content (mainly, the concreteness of the designated events); elements of depiction (Clark [Reference Clark2016]), such as sound effects and direct speech representation; and grammatical simplicity as reflecting the immediacy of actual experience (Toolan [Reference Toolan1988: 126]; Kroon [Reference Kroon, Sawicki and Shalev2002]; Allan [Reference Allan, Bakker and Wakker2009 etc.]). Finally, I present qualitative studies to suggest that the preference for the mimetic mode of narrative presentation is stronger when the narrated events are high in communicative dynamism, that is, if they are particularly newsworthy or relevant to the discourse (McNeill [Reference McNeill1992], [2005]).Footnote 6

I.2.2.2 Summary Narrative and the Diegetic Present

In Chapter 3, I discuss the use of the present for preterite in summary narrative, which is distinguished from scenic narrative by a higher degree of abstraction and temporal compression (short stretches of discourse covering large stretches of story time). This is illustrated by the following example:

Τοῦ δ’ αὐτοῦ χειμῶνος Μεγαρῆς τε τὰ μακρὰ τείχη, ἃ σφῶν οἱ Ἀθηναῖοι εἶχον, κατέσκαψαν ἑλόντες ἐς ἔδαφος, καὶ Βρασίδας μετὰ τὴν Ἀμφιπόλεως ἅλωσιν ἔχων τοὺς ξυμμάχους στρατεύει ἐπὶ τὴν Ἀκτὴν καλουμένην.

The same winter, the Megarians razed the long walls, which had been occupied by the Athenians, to the foundations; and Brasidas, after the capture of Amphipolis, makes an expedition with the allied forces against the area called Acte.

There is a minimum of concrete detail in these descriptions, and the designated events in this short piece of discourse must have taken a long time to actually occur. This mode of narrative presentation retains little of the character of immediate experience. In such contexts, the character of the present for preterite is no longer mimetic but diegetic. What facilitates the construal of the designated past events as presently accessible in this case is the conceptualisation of the discourse as a representation. As the narrative progresses, we construe a mental model of the discourse that keeps track of the events and entities that are evoked (for the mental discourse model, see, e.g., Cornish [Reference Cornish2010], [2011]; Kroon [Reference Kroon2017]). The present for preterite serves to highlight the designated event as the current object of joint attention. This tends to be done at salient changes in the structure of the discourse – in particular, at changes in the narrative dynamic and at changes in the status of referents.Footnote 7 To corroborate this argument, I show that the present for preterite has a predilection for certain attention-management strategies and also explore other hypotheses pertaining to the relationship between tense usage and discourse structure.

I.2.2.3 Zero-Degree Narrativity and the Registering Present

Finally, Chapter 4 focuses on the present for preterite in isolated references to past events in non-narrative contexts (zero-degree narrativity, Stanzel [1989: ch. 2]; ‘cancellation of narrative experientiality’, Fludernik [Reference Fludernik1996: 28]; on Classical Greek, see Huitink [Reference Huitink, Willi and Derron2019: 188–95]). An example is the following:

The relative clause beginning with οὕς (‘that’) contains a stand-alone reference to a past event within the context of an exhortation that is concerned with the present situation. The use of the present for preterite in such contexts is particularly interesting because it belies the common assumption that tense-switching is confined to narrative discourse (e.g., Fleischman [Reference Fleischman1990: 65]; Rijksbaron [Reference Rijksbaron, de Jong and Rijksbaron2006: 127], [2011c]; Thoma [Reference Thoma2011: 2374, with references]). Classicists confronted with such cases have often tried to explain them away by giving the present tense a special semantic value here.Footnote 8 I have presented a detailed technical argument against this procedure elsewhere (Nijk [Reference Nijk2016a]; see also Schuren [Reference Schuren2014: 129–30]). Those who do take these cases as genuine present for preterite forms (as annalistic or registering present – I will use the latter term)Footnote 9 have had difficulties explaining the semantics and pragmatic function of the present tense here.Footnote 10 Most informative is the account of Allan (Reference Allan and Lallot2011b: 246), who argues that the registering present is used to highlight ‘milestone events in the past which are viewed as still relevant to the narrator’s present’. I agree with this characterisation, but the question remains how exactly the function of highlighting milestone events is related to the semantics of the present tense; the notion of ‘present relevance’ is, to my mind, not specific enough as an explanation.

I will argue that the registering present evokes the present accessibility of the designated event on some kind of record. I understand the concept of a ‘record’ in a broad sense here. It may be an actual physical entity, such as an iconographical representation, a mythographical or annalistic text, a document recording a transaction, et cetera. But events can also be conceived as being ‘on record’ in a more abstract, cognitive sense – for example, in terms of being generally recognised landmark events in history (such as, from our perspective, Caesar crossing the Rubicon) or as constituting officially authorised transactions (such as a marriages, which required a verbal contract). The pragmatic function of the registering present is to signal that the designated event is well-established in shared cultural memory, which serves both to elevate the status of this event (giving it an ‘official’ or ‘canonical’ air) and to underline the legitimacy of the speaker’s assertion.Footnote 11 This registering use of the present is marginal, which makes it difficult to corroborate this account with quantitative data, so I will confine myself to qualitative analyses here.

***

In Sections I.3 and I.4, I will briefly lay out the theoretical foundations of this study. Section I.3 clarifies aspects of Mental Spaces Theory that will be of key importance to my analysis of the semantics of the present tense. Section I.4 discusses tense, aspect and actionality in Classical Greek. After this, Section I.5 ends with a note on how to read the translations presented in this book.

I.3 Conceptualising Time: Theoretical Background

In this study, I start from the assumption, common to cognitive theories of language, that linguistic meaning resides in the conceptual structure evoked by an expression.Footnote 12 In order to describe the conceptual structure evoked by the tense categories, I will make use of the framework of Mental Spaces Theory (Fauconnier [Reference Fauconnier and Fauconnier1994 {1984}]; Fauconnier and Turner [Reference Fauconnier and Turner2002], [2006]). In this section, I will briefly describe the concepts that will be central to my argument in this study.

Mental spaces are ‘small conceptual packets constructed as we think and talk, for purposes of local understanding and action’ (e.g., Fauconnier and Turner [Reference Fauconnier, Turner and Geeraerts2006: 307]). For example, talking about France involves the construal of a mental space whose conceptual content consists in our activated knowledge about the country. The content of mental spaces can be elaborated by the discourse (we may be told something new about France) and mental spaces may become interconnected or integrated into a larger whole (‘France’ and ‘Germany’ may be integrated into ‘Europe’).

Three mental space types are important to my argument: (a) the ground space, or, alternatively, ‘base space’; (b) distal event spaces and (c) representation spaces.

The ground space represents the immediate reality, the ‘here and now’, of the speaker and addressees. The ground space is actually best understood as a network of spaces, each representing a distinct domain of this immediate reality, such as the physical surroundings, the discourse, et cetera.Footnote 13 The ground is constantly changing as time moves on, the discourse evolves and, optionally, as the speech partners move around (such as when talking while taking a walk). As deictic expressions, the tenses are anchored in the ground. The present tense signals that the designated event coincides with the time of the ground, that is, the small time window we experience as ‘now’ (see Section I.1.2); the past tense signals that the designated event is anterior to the time of the ground.

In written communication, where there is temporal distance between the sending (writing) and the receiving (reading) of the message, the author may construe the ground either as the time of writing or the anticipated moment in the future when the addressee will read the message (Vuillaume [Reference Vuillaume1990: 25–31]; Récanati [Reference Récanati1995]). For example, I might say in a letter By the time you read this, I will be in Canada (ground = time of writing) or, alternatively, As you read this, I am already waiting for your response (ground = time of reading). This is a consideration in historiographical prose, which is part of my Classical Greek corpus. Generally, when the distinction is relevant at all in the passages I discuss, we can take the time of reading as the default for the construal of the ground. For example, Herodotus sometimes explicitly refers to his own time with the past tense, as in τὰ δὲ ἐπ’ ἐμέο ἦν μεγάλα, πρότερον ἦν σμικρά (‘and the [cities] that were big in my time were small before that’; Histories 1.5). The implication is that the ground as Herodotus construes it is posterior to the time of writing. I also note Thucydides’ use of the perfect form γέγραπται (‘have been written down’) to refer to events he is about to describe, which again presupposes a ground that is posterior to the time of the writing process itself (Histories 2.1.1). In my interpretation, then, the default ground in these texts is reconstituted at any time a reader engages with it: the ‘present’ is the moment the author’s message lands with the reader.

Distal event spaces represent events that are conceived as being non-coincidental with the time of the ground. I will be concerned here mainly with past event spaces. For example, when I say In 399 bc, Socrates was executed, I set up a distal event space representing the year 399 bc and add content to that space.Footnote 14

Representation spaces form the crux of my argument. As Sweetser and Fauconnier (Reference Sweetser, Fauconnier, Fauconnier and Sweetser1996: 2) explain, ‘[a]ny concept of representation inherently involves two mental spaces, one primary and the other dependent on it’. Consider Figure I.1. To interpret the picture we have to understand that it is meant to represent an actual event.Footnote 15 To construe the picture as a representation space automatically entails setting up an actual past event space that contains the represented event. Mappings are established between the two spaces, so that the actual Ryan Pitts and the actual President Obama are linked to the figures in the picture. At the same time, we remain clearly aware that the ‘world of the representation’ is distinct from the real world (the picture may be modified without changing the actual event).

Figure I.1 Obama awards Medal Of Honor to retired army staff sargent Ryan Pitts

This example already reveals how the concept of representation spaces is potentially interesting for understanding the use of the present tense to refer to past events. The caption under the picture reads: Obama awards Medal of Honor to retired army staff sargent Ryan Pitts. The use of the present tense is entirely natural here, as it seems obvious that what is referred to is the event as seen in the representation space, which is immediately visually accessible from the ground.Footnote 16 Crucially, however, authors can use different tenses to alternatively highlight a present representation space or a past event space, even when referring to the same event or closely related events. I give two examples from Robert Caro’s The years of Lyndon Johnson: Master of the senate (2002).

First, the following caption accompanies a picture of Lyndon Johnson speaking to John F. Kennedy, George Smathers and other senators:

On August 29, 1957, still Majority Leader because of William Proxmire’s election, Johnson emphasizes a point after Proxmire was sworn in.

The phrase on August 29, 1957 designates the actual past event space. Reference to the representation space would be something like in this picture. The present tense form emphasizes designates the event as seen in the picture. The alternative would, obviously, be the past tense – which we actually find in the next sentence. The switch to the past tense can be explained by the fact that the event designated here forms the historical context to the picture and cannot be immediately accessed by looking at it.

Second, consider the following passage from the introduction of the book:

This book is in part the story of that man, Lyndon Baines Johnson. He is not yet the thirty-sixth President of the United States, but a senator… And the Lyndon Johnson of this book is very different from the man Americans would later come to know as president.

His physical appearance was strikingly different. He was a tall man.

The use of present tense forms in the first paragraph depends upon a conceptual scenario where Lyndon Johnson is construed as immediately accessible in the book (note the Lyndon Johnson of this book). In other words, to read the story of Lyndon Johnson is to ‘witness’ Lyndon Johnson in a representation space. In the second paragraph, by contrast, the author puts the actual past event space in focus by using the past tense. The switch may be motivated by the transition from a general description of Johnson as the topic of the book (he is a senator, not yet president, as he will be in the next book) to a more specific description of his appearance at the time of his senatorship.

The important point is that the concept of representation affords an author or speaker the choice of different tenses to refer to essentially the same event. In Chapter 1, I will elaborate in detail on how this bears on the phenomenon of tense-switching in different contexts.

I.4 Tense, Aspect and Actionality in Classical Greek

In this section, I will discuss tense, aspect and actionality in Classical Greek, focusing on those aspects that pertain to tense-switching and have informed my criteria for selecting data for statistical analysis (see Chapter 2, Section 2.1.1, and Appendix, Section A.2).

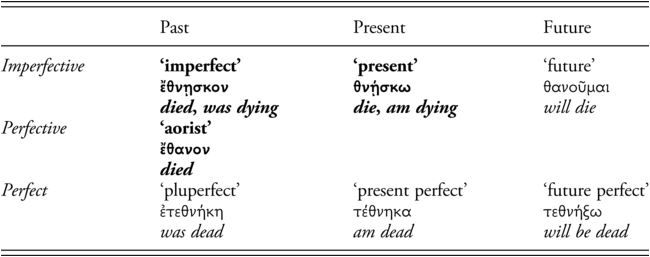

There are three tenses in Classical Greek: past, present and future. In the past tense there is an aspectual distinction between perfective and imperfective. All three tenses have a perfect form. The state of affairs is schematised in Table I.1; throughout this study, we will be mainly concerned with the boldfaced forms. I use the first person forms of the verb θνῄσκω ‘die’ as examples. I will not delve into the morphology of these categories, except in so far as I address the issue of morphological ambiguity in Section I.4.3.

Table I.1 Tense and aspect in Classical Greek

| Past | Present | Future | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Imperfective | ‘imperfect’ ἔθνῃσκον died, was dying | ‘present’ θνῄσκω die, am dying | ‘future’ θανοῦμαι will die |

| Perfective | ‘aorist’ ἔθανον died | ||

| Perfect | ‘pluperfect’ ἐτεθνήκη was dead | ‘present perfect’ τέθνηκα am dead | ‘future perfect’ τεθνήξω will be dead |

I will first briefly touch upon tense (Section I.4.1), leaving the deeper theoretical discussion for later (Chapter 1, Section 1.2). Then I discuss aspect (Section I.4.2). After the section on morphological ambiguity, I turn to actionality (Section I.4.4) and offer some observations on the relationship between aspect and actionality (Section I.4.5). Finally, I summarise the main takeaways of this discussion for the remainder of this study (Section I.4.6).

I.4.1 Tense

The functions of the Classical Greek tenses are similar to those in modern European languages such as English, German or French. The present tense is typically used to designate events that are coincidental with the time of the ground (i.e., the speaker’s present), while the past and future tenses typically designate events that are anterior and posterior (respectively) to the time of the ground.

The past and future tenses also have non-temporal, epistemic meanings. The past tense is used in counterfactual statements, while the future tense can signal that the speaker considers the designated event or situation probable (as in English, That will be the postman instead of That is probably the postman; compare de Saussure [2013: 60–7]). These functions will not concern us further in this introduction, but I will address the relationship between the temporal and epistemic meanings of the tenses in Chapter 1, Section 1.2 (and see Langacker [Reference Langacker, Patard and Brisard2011]).

The range of meanings of the present tense in different languages is notorious. Beside referring to events taking place in the actual present of the speaker, the present can also refer to the generic and habitual domain: The Dean’s Conference meets on Thursdays (Fleischman [Reference Fleischman1990: 34]), συσσιτοῦμεν γὰρ δὴ ἐγώ τε καὶ Μελησίας ὅδε (‘Me and Melesias here take our meals together’; Plato, Laches 179b). Note that such habitual and generic statements are still bound to a certain temporal domain (habits and generic truths can change), so the notion of present time is still relevant in such examples.

However, the present tense can also be used to refer to the temporal domains of the past and future. As for the former, we have already seen this (examples [1], [4]–[6]); examples of the present tense referring to the future are the following: I leave/am leaving for Paris next week (Fleischman [Reference Fleischman1990: 34]), γίγνει γάρ, ὡς ὁ χρησμὸς οὑτοσὶ λέγει, | ἀνὴρ μέγιστος (‘for you [will] become, as this oracle here says, a very great man’; Aristophanes, Knights 177–8). The key question is whether such uses can be accounted for somehow in terms of present time reference. As this is the main subject of the present investigation, I will leave it for the moment, to pick it up in Chapter 1, Section 1.2. For now it suffices to have provided a sketch of the Classical Greek tenses and their functions.

I.4.2 Aspect

Aspect (or ‘grammatical aspect’ as opposed to ‘lexical aspect’, which I here call ‘actionality’) concerns the way the designated event is construed in relation to viewpoint. In Classical Greek, there is an opposition between perfective and imperfective aspect in the past tense (‘aorist’ versus ‘imperfect’). As a working definition, we may say that the perfective construes the designated event as a bounded whole, while the imperfective leaves the boundaries of the designated event out of focus (compare, e.g., Langacker (Reference Langacker2008: 136–9]). Consider the following example:

οὑμὸς πατὴρ Κέφαλος ἐπείσθη μὲν ὑπὸ Περικλέους εἰς ταύτην τὴν γῆν ἀφικέσθαι, ἔτη δὲ τριάκοντα ᾤκησε, καὶ οὐδενὶ πώποτε οὔτε ἡμεῖς οὔτε ἐκεῖνος δίκην οὔτε ἐδικασάμεθα οὔτε ἐφύγομεν, ἀλλ᾽ οὕτως ᾠκοῦμεν δημοκρατούμενοι ὥστε μήτε εἰς τοὺς ἄλλους ἐξαμαρτάνειν μήτε ὑπὸ τῶν ἄλλων ἀδικεῖσθαι.

My father Cephalus was persuaded by Pericles to come to this country, and he livedAor here for thirty years, and neither he nor any other of us ever sued anyone or was ever sued, but we livedImp in such a way under the democracy as to do others no wrong nor be wronged by others.

The aorist ᾤκησε (‘lived’) construes the designated event as a bounded whole: the temporal boundaries are explicitly specified (ἔτη … τριάκοντα [‘thirty years’]). The imperfect ᾠκοῦμεν (‘lived’), by contrast, focuses on the character and internal constitution of the designated event. Any subpart of the designated event may serve to illustrate the behaviour of the speaker’s family during this time.Footnote 17 While such examples are relatively straightforward, in practice the variation between the aorist and the imperfect is often motivated by subtler considerations, and this is one of the most difficult issues in Classical Greek linguistics.Footnote 18

In the present tense, there is no form for perfective aspect. Present perfectives are a cross-linguistic rarity (e.g., Timberlake [2007: 298–9]). Their absence is usually explained in terms of a clash between present time reference and perfective aspectual construal: things that are described as occurring ‘here and now’ are typically ongoing.Footnote 19 In any case, the result is that when a speaker of Classical Greek uses the present to refer to the past, no overt aspectual distinctions can be made.

This would logically lead to the conclusion that the present for preterite is neutral with respect to aspect. It has been observed, however, that this present does not stand in the same relationship to the aorist as it does to the imperfect. Typically, present forms referring to the past seem to be interchangeable with aorists from an aspectual point of view. Scholars differ in their allowance of an ‘imperfective’ use (Boter [Reference Boter2012: 209] cites some contrasting views in the standard grammars). It has even been argued that the present for preterite conveys a kind of ‘hyperpunctuality’ (George [Reference George and Lallot2011]), which is to say that it puts the internal constitution of the designated event completely out of focus.

However, even though the majority of instances seem aoristic, there are cases where it is clear that the aspectually appropriate preterite form must have been the imperfect (compare Fanning [Reference Fanning1990: 228]). Thus, the present for preterite has an implicit aspectual value that must be derived from the semantics of the verb phrase (see Section I.4.4) and the context. As a general rule, we can state the following: the aspectual construal of a present for preterite form is likely to be imperfective when the event it designates (A) and the next event on the narrative main line (B) stand in either of the following relations to each other:

(a) A and B temporally overlap (A is still going on when B occurs);

(b) B marks the end of A (which means that the endpoint was not inherent in A).

Consider the following example:

οἱ δὲ διερευνηταὶ ὡς εἶδον ταῦτα, αὐτοί τε ἐδίωκον καὶ τῷ Γαδάτᾳ κατέσειον· καὶ ὃς ἐξαπατηθεὶς διώκει ἀνὰ κράτος. οἱ δὲ Ἀσσύριοι, ὡς ἐδόκει ἁλώσιμος εἶναι ὁ Γαδάτας, ἀνίστανται ἐκ τῆς ἐνέδρας. καὶ οἱ μὲν ἀμφὶ Γαδάταν ἰδόντες ὥσπερ εἰκὸς ἔφευγον, οἱ δ’ αὖ ὥσπερ εἰκὸς ἐδίωκον.

When the scouts saw that, they pursued them and beckoned Gatadas [to follow their example]; and he {was deceived} and pursues them energetically. And when the Assyrians judged that Gatadas could be taken, they rise from their ambush. When those around Gatadas saw this they fled, as was natural; and the enemy went in pursuit, as was natural also.

Gatadas’ pursuit, marked with the present διώκει (‘pursues’), is still going on when the Assyrians rise from their ambush (ἀνίστανται [‘rise’]). Moreover, when Gatadas’ companions saw this, they fled. Thus, the pursuit was abandoned. For these reasons, the implicit aspectual construal of διώκει (‘pursues’) must be imperfective. A list of such cases may be found in the Appendix.

Finally, a note on the perfect (not ‘perfective’) aspect. The perfect generally signals the continuing relevance, at the time of the active viewpoint, of a certain event anterior to that viewpoint (e.g., Orriens [Reference Orriens, Bakker and Wakker2009]; Nijk [Reference Nijk2013b]; Crellin [Reference Crellin, Crellin and Jügel2020] provides a historical discussion). In its most typical use, it designates a state that is the result of the completion of an anterior event, as in τέθνηκα (‘I have died/am dead’). The stative value of the perfect will be important later on (Section I.4.5).Footnote 20

I.4.3 Tense and Grammatical Aspect: Morphological Ambiguity

There are two kinds of morphological ambiguity that pertain to the present study: that between present and imperfect forms and that between imperfect and aorist forms. Of these two, the first is the most important (compare Rijksbaron [Reference Rijksbaron, de Jong and Rijksbaron2006]).

Past tense forms are normally marked in Classical Greek with a prefix called the augment, ἐ-. When the verb stem begins with a vowel, augmentation may consist in lengthening of that vowel, for example, present ἐ-λαύνω, imperfect ἤ-λαυνον. Sometimes, the augment may be ‘invisible’. Normally, the ending still betrays the tense, but there are exceptions. The third person singular ending is -ει for present forms and, usually, -ε for past tense forms; however, some types of verbs have a third person ending that is identical in the present and in the imperfect (so-called contract verbs with a stem ending in -ε). Also, the endings of the first person plural (which is used much more rarely in narrative) are the same for the present and the imperfect. When there is no augment to make the distinction, such forms are morphologically ambiguous.

This occurs, first, with verbs that have a long vowel at the beginning of the stem. For example, the present stem ὠθε- (‘push’) remains unaltered in the imperfect. The third person form ὠθει is thus morphologically ambiguous between the imperfect and the present. In modern text editions, the tense difference is marked by the accent: present forms are accentuated with a circumflex on the final syllable (ὠθεῖ), while imperfects are accentuated with an acute on the penultimate syllable (ὤθει). However, this accentuation was added by later scribes and scholars and was not in the original texts. (This problem extends to verbs beginning with vowels that are not marked for length: e.g., a short o sound is rendered with an omicron, while a long o sound is rendered with an omega; but this does not hold for the i and u sounds.)

Secondly, in drama the augment is sometimes omitted for metrical convenience. Consequently, all third person forms of contract verbs with a stem ending in -ε are morphologically ambiguous here. Now, it is true that the undoubtable evidence for the omission of the augment in drama (i.e., from verb forms where the ending betrays the past tense) is relatively scarce (see Bergson [Reference Bergson1953: 126]; also Lautensach [Reference Lautensach1899: 165–74]; Page [Reference Page1938] ad Medea 1141). Nevertheless, it does exist, and there are specific cases of morphologically ambiguous forms where the tense is unlikely to be present. For example, Sophocles, Philoctetes 371 reads, in the editor’s edition: ὁ δ’ εἶπ’ Ὀδυσσεύς, πλησίον γὰρ ὢν κυρεῖ (‘and Odysseus said, for he happens to be present’). Here Rijksbaron (Reference Rijksbaron, de Jong and Rijksbaron2006: 141–4) is almost certainly right in arguing that the correct reading is in fact κύρει (‘happened’), an unaugmented imperfect form, as there is no good parallel for the present for preterite in an explanatory clause referring to a background situation (note also the use of the past tense in the main clause).

In short, morphologically ambiguous cases such as these form a methodological problem for the statistical analyses presented in Chapter 2, which is mainly concerned with drama. I will excise these cases from my data set, except when it can be argued with reasonable certainty that the aspectual construal must be perfective, so that reading the form as an imperfect is out of the question. An example is the following:

κἄπραξε δεινά· διὰ μέσου γὰρ αὐχένος ὠθεῖ σίδηρον.

And she did a terrible deed, for she drives the sword right through her neck.

The form ὠθεῖ (‘drives’) could technically be read as an imperfect ὤθει (‘drove’) but an imperfective construal would seem out of place in this case, as the designated event is short in duration and completed without any complications.

The second kind of morphological ambiguity is between aorist and imperfect forms. There is no need here to delve into the sound laws that have produced the ambiguity; examples of such forms are ἔκτεινε (‘killed’), ἔκρινε (‘judged’). It suffices to say that the phenomenon is relatively rare, only occurs in the third person singular and that, in most instances, it can be established with reasonable certainty which aspectual construal is intended. All in all, this is only a marginal issue. More details are discussed in the Appendix.

I.4.4 Actionality

Actionality (or ‘lexical aspect’, or Aktionsart) concerns the inherent event-structural properties of the event designated by a verb phrase.Footnote 21 I will use the traditional Vendlerian (Reference van Dijk and Tannen1957) categorisation of four actional profiles: state, activity, accomplishment and achievement (see also, e.g., Bertinetto and Delfitto [Reference Bertinetto, Delfitto and Dahl2000]; Fanning [Reference Fanning1990] on New Testament Greek; Napoli [2006] on Homeric Greek). The differences between these types can be described in terms of three parameters:

(a) Telicity: does the designated event have an inherent endpoint?

(b) Dynamicity: does the designated event involve change?

(c) Durativity: does the designated event last longer than a moment?

States are atelic and durative. Moreover, they are non-dynamic: states are steady over time. Examples are εἰμί (‘be’), βασιλεύω (‘be king’), ὑγιαίνω (‘be healthy’). Activities, like states, are atelic and durative, but unlike states, they are dynamic: they involve change and require some effort or energy to be continued. Examples are ᾄδω (‘sing’), δακρύω (‘cry’), διαλέγομαι (‘converse’).

That states and activities are atelic does not mean that they never end. A king can be dethroned, health conditions can change, a singer will at one point stop singing and so on. The point is that such circumstances are not an inherent part of the semantics of the verb phrase. States and activities can, in principle, be extended indefinitely, until some arbitrary ending is imposed on them.

Telic verb phrases are by their nature dynamic: if something has an inherent endpoint, then it naturally involves change. Within the category of telic verb phrases, a distinction is made between accomplishments, which have some substantial duration, and achievements, which are momentaneous. Examples of accomplishments are ποιέω in the sense ‘make’ with a concrete object, περάω (‘cross [usually a body of water]’), κατεσθίω (‘eat up’). These events all take some time to reach completion. Examples of achievements are πτάρνυμαι (‘sneeze’), παίω (‘hit’), εὑρίσκω (‘find’).

Similarly to the debate concerning the compatibility of the present for preterite with imperfective aspectual construal, there is discussion as to whether it can be used with atelic verb phrases.Footnote 22 Boter (Reference Boter2012) sought to refute the idea that the present for preterite is confined to telic verb phrases, for which view he points mainly to Ruipérez (1954) and Rijksbaron (Reference Rijksbaron, de Jong and Rijksbaron2006, Reference Rijksbaron and Lallot2011a). Rijksbaron (Reference Rijksbaron2015) in turn subjected Boter’s arguments to a detailed critique, arguing that his alleged atelic present for preterite forms are either not really atelic or, in other cases, do not refer to the past but to the actual present.

In my view, the present for preterite is in fact used with atelic verb phrases, although this use is relatively uncommon. Consider the following example:

The present πίνει (‘drinks’) designates the activity of drinking an unspecified quantity of wine. The presence of a subordinate clause introduced by ἕως (‘until’) is a diagnostic for the atelicity of the verb phrase: the external imposition of an endpoint on the designated event implies that it is not inherently telic.Footnote 23 Further discussion of this issue will be found in the Appendix.

I.4.5 Distinguishing Aspect from Actionality

In analysing the aspectual and actional usage of the present for preterite, it is important to maintain a clear distinction between the two parameters. To be sure, it is possible for aspect to affect the actionality of the verb phrase. The perfective aspect can turn a state into an achievement. This is called the ‘ingressive’ interpretation of the perfective aspect. For example, the present ἔχω means ‘have’, but the aorist ἔσχον means ‘acquire’, that is, it designates the momentaneous event of passing from the state of not-having into the state of having.

Generally speaking, however, aspect and actionality should be kept distinct. In particular, I feel it is necessary to shed some light on the debate between Boter (Reference Boter2012) and Rijksbaron (Reference Rijksbaron2015) concerning the relationship between the present for preterite and actionality, which suffers from a lack of clarity in this respect.

To begin with, Boter’s (Reference Boter2012: 208–9) introduction to the matter is already a little confusing. Take the following passage:

Roughly speaking, the HP instead of an aorist refers to a completed event, the HP instead of an imperfect to an activity or a state which is extended in time. For this distinction the classification of Aktionsarten of the verb introduced by Vendler (Reference van Dijk and Tannen1957) and developed by later scholars has become universally accepted.

This suggests that there is a one-to-one correspondence between Vendlerian actionalities and different types of grammatical aspect. As a whole, the paper certainly does not bear out that this is what is actually meant, but the distinction could have been made more clear from the outset. I will elaborate on the importance of this point in a moment.

Some disambiguation is needed with respect to the relationship between durativity or ‘being-extended-in-time’ and the actional class of activity. In the terminology I adopt, ‘durativity’ designates the event-structural quality of longer-than-momentaneous duration. Atelic verb phrases are durative by nature, but telic verb phrases can also be durative (the accomplishment class). Rijksbaron (Reference Rijksbaron and Lallot2011a: 7) seems to take ‘durative’ as synonymous with ‘process’ (i.e., ‘activity’). In itself, this is not necessarily objectionable, but things become muddled later in the debate. At one point, Boter (Reference Boter2012: 225) says:

The case is different, however, with περισκοπῶ [‘look around’] in [Sophocles, Electra] 897. This verb is qualitate qua nonpunctual because ‘look around’ necessarily takes up some time and therefore it indicates an Activity.

But telic verb phrases can also be nonpunctual. The point is that looking around is something that can be extended indefinitely, and therefore it is (as Boter rightly points out) an activity. Similarly, at page 210: ‘[F]urther, there are passages where the HP of not strictly static verbs (like τρέφω, ὁρῶ, and διέρχομαι) refers to an Activity which is extended in time and/or atelic.’ It is not a matter of ‘and/or’; for a verb phrase to belong to the activity class, it must be atelic. In short, I think it is better to clearly distinguish between durativity as an actional parameter and the actionality of activity.

Two discussions by Rijksbaron (Reference Rijksbaron2015) will illustrate the importance of a proper understanding of the relationship between aspect and actionality. In Euripides, Medea 1163–4, we find the verb phrase διέρχεται στέγας, translated by Kovacs as ‘she paraded about the room’. Actually ‘paraded’ renders a present for preterite (‘parades’). Now, Boter (2012: 211) points out that ‘parading about the room’ is an activity and that therefore Rijksbaron (2002: 23), by adopting Kovacs’ translation ‘paraded’ in his discussion of the passage, refutes his own claim that the present for preterite is confined to telic verb phrases. Rijksbaron replies:

Actually, I did nothing of the kind, for my translation of διέρχεται στέγας (which is that of Kovacs) runs: ‘she paraded about the room’. There is then a simple past in my translation, not a progressive form. Boter’s ‘parading’ makes the sentence of course durative and indeed atelic.

First off, I think Boter’s rendering ‘parading’ is meant as a gerund, that is, an abstract representation of the meaning of the entire verb (instead of the infinitive ‘parade’). In any case, what Rijksbaron does here is to confuse aspect with actionality. ‘To parade about a room’ is an activity, which in principle can be extended indefinitely. The aspectual construal imposed on this activity by the grammatical form of the verb is another matter.Footnote 24

In another instance, the opposite fallacy occurs. In Sophocles, Women of Trachis 698, we find the perfect form κατέψηκται (χθονί), literally ‘lies crumbled (on the ground)’. According to Boter (Reference Boter2012: 215) this is a ‘historical perfect’, that is, a perfect instead of a pluperfect, referring to the past. Rijksbaron (Reference Rijksbaron2015: 231–2) is skeptical: ‘κατέψηκται is perhaps a historical perfect, but it might as well be an actual perfect. Note that they all three [κατέψηκται and the preceding two present forms] express telic states of affairs.’ What interests me here is Rijksbaron’s claim that the perfect κατέψηκται designates a telic event. It is true that the verb καταψήχομαι (‘crumble away’) is telic. However, the perfect aspect does not designate the event of crumbling away but the resulting situation (see Section I.4.2). In the case of the perfect aspect, the aspectual construal does change the way we should view the actionality of the verb phrase in context. For all present purposes, the perfect form κατέψηκται (‘lies crumbled’) designates a state. If the verb is a ‘historical perfect’ then it is practically an instance of an atelic present referring to the past.

To conclude, the difference between actionality and aspectual construal is that actionality is inherent in the semantics of the verb phrase, while aspectual construal imposes a certain viewpoint on the event designated by the verb phrase. We should maintain a principled distinction between the two. In certain cases, however, we should allow for the aspectual construal to influence the actionality of the verb phrase in a specific context, in particular with the ‘ingressive’ aorist and with the perfect aspect designating a result state.

I.4.6 Takeaways

In conclusion, the following peculiarities of the Classical Greek tense and aspect system, as related to the investigation of the use of the present for preterite, should be kept in mind:

(a) When the present is used to refer to past events, aspectual marking is lost. The present has no inherent aspectual value in these cases, but the aspectual construal is implicit and must be derived from the semantics of the verb phrase and the context. The implicit aspectual construal of the present for preterite is usually perfective (or ‘aoristic’).

(b) Certain verb forms are morphologically ambiguous between present and imperfect. This is mostly a concern in drama. I have excised such cases from my data set when doing statistical analysis, except when the aspectual construal was most probably perfective.

(c) Actionality concerns the inherent event-structural properties of the verb phrase in terms of telicity, dynamicity and durativity. The present for preterite is typically used with telic verb phrases, but sometimes with atelic verb phrases as well.

(d) The parameters of aspect and actionality should be kept distinct as much as possible. However, in some cases aspectual construal influences actionality: the ‘ingressive’ aorist turns states into achievements, and perfect forms have stative value even though the inherent actionality of the verb phrase may be telic.

I.5 A Note on the Translations

In my translations, I highlight relevant present forms using boldface type. Past tense forms are underlined. I do not generally mark verb forms for aspectuality as I am mainly concerned with the contrast between the tenses, but I do refer to preterite forms with aspectual designations in my discussions of passages (‘imperfect form X’, ‘aorist form Y’).

One peculiarity of the Classical Greek language that is especially challenging for translators is its predilection for participial clauses. I have tried to preserve these in translation as much as possible, but sometimes using a separate main clause resulted in a more natural translation. In such cases, I have put the verb in the translation that represents the participle in the original between accolades { }. To give an example:

Παρελθὼν δ’ ὁ μισοφίλιππος Δημοσθένης, κατέτριψε τὴν ἡμέραν ἀπολογούμενος.

The Philip-hating Demosthenes {came forward} and spent the whole day on his defense speech.

The phrase ‘came forward’ renders the aorist participle παρελθών, which might be rendered more literally ‘after coming forward’. As participles do not inherently refer to a specific temporal domain, these verbs should be disregarded in the analysis of tense usage.

Finally, I insert material between square brackets [ ] to clarify what is not made explicit in the original. For example, in Thucydides, Histories 8.38.1, the phrase μετὰ ταύτας τὰς ξυνθήκας literally means ‘after that agreement’, but I render ‘after [the establishment of] that agreement’.