Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- List of Illustrations

- Note on Transliteration

- Introduction: Material Culture and Mysticism in the Persianate World

- Part I

- Part II

- Conclusion

- Appendix A List of Khamsa Silks

- Appendix B Summary of ‘Shirin and Khusrau’ by Amir Khusrau Dihlavi

- Appendix C Summary of ‘Majnun and Layla’ by Amir Khusrau Dihlavi

- Glossary of Textile Terms

- Glossary of Persian and Arabic Terms

- List of Historic Figures

- Index

1 - Silks, Signatures and Self-fashioning

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 19 April 2023

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- List of Illustrations

- Note on Transliteration

- Introduction: Material Culture and Mysticism in the Persianate World

- Part I

- Part II

- Conclusion

- Appendix A List of Khamsa Silks

- Appendix B Summary of ‘Shirin and Khusrau’ by Amir Khusrau Dihlavi

- Appendix C Summary of ‘Majnun and Layla’ by Amir Khusrau Dihlavi

- Glossary of Textile Terms

- Glossary of Persian and Arabic Terms

- List of Historic Figures

- Index

Summary

Abstract

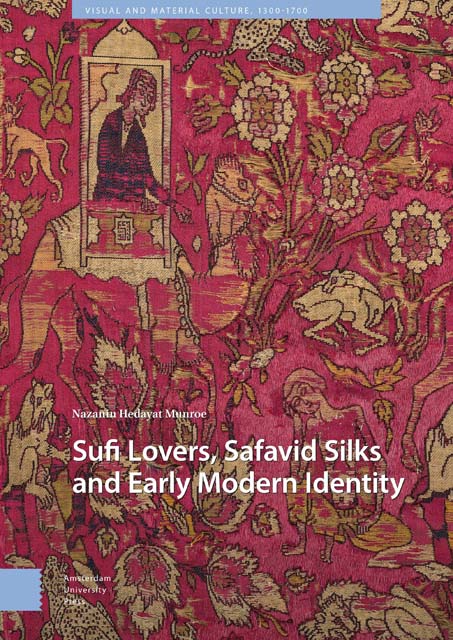

Presenting a literature review of silks depicting love scenes from Khamsa poetry, this chapter introduces garments displaying the characters as a mode of selffashioning. The scenes originated from twelfth-century Persian-language poetry, reproduced as textiles in the Safavid period between 1550 and 1650. Three silk designs include the signature of Ghiyath al-Din, a naqshband (‘textile designer’) from Yazd, Iran, presented as both a royally sponsored artist and a Sufi, representing the paradox of luxury and mystic practice. The concept and etymology of naqshband and the organization of textile workshops in the Safavid period is discussed in conjunction with consumption and patronage. Resembling Khamsa manuscript paintings produced in the same period, the silks featured in this study point to a collaboration between painters and silk designers, whose workshops were separate.

Keywords: Nizami Ganjavi, Safavid silk weaving, Layla and Majnun, Khusrau and Shirin

Though earlier scholars have certainly referenced silks depicting Khamsa characters to exemplify the high level of accomplishment in Safavid weaving, prior to my doctoral dissertation the group had never been analyzed as a whole. Examining primary source materials, passages from Nizami’s original text and iconography in both textiles and paintings, this book further develops the theory that fashioning these textiles into garments represents a connection between the wearer and the characters displayed on one’s outer clothing: an external representation of the internal self. The analysis further elaborates the important link of Sufi practice as integral to experiencing the world through the eyes of the lover, representing the mystic aspirant.

It should be noted at the onset that many of the surviving Khamsa silks are fragments, most of which are known through publications by museums outside the Persianate world. As earlier scholars note, the fragments mysteriously appeared at auctions, were sold by dealers, or acquired by private collectors, with little documentation of provenance other than the location of acquisition. The most lucrative and convenient way to resell what may have been an intact garment or large piece was to cut it into small pieces and sell them as fragments. This requires the textile historian to utilize original approaches for writing about extant materials relative to other textual and visual evidence, such as whether the silks were fashioned into garments or utilized in other ways.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Sufi Lovers, Safavid Silks and Early Modern Identity , pp. 27 - 52Publisher: Amsterdam University PressPrint publication year: 2023