Book contents

3 - Modern and Contemporary Times

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 August 2012

Summary

VIEWING THE LUPA WITH NINETEENTH-CENTURY VISITORS

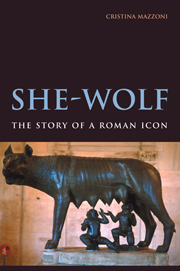

Travelers to rome often wrote of the bronze lupa: they wrote to show off their knowledge or to admit their ignorance; they wrote in fear or in admiration; they were by turns irritated by the she-wolf's ubiquity or stunned by the beast's persistence. More or less consciously, they identified in the statue the multiple layers that give her – and Rome – their stratified essence, their palimpsest appearance. In these texts, even as the statue's meanings accrue with each passing year and as the She-Wolf comes to embody an increasingly longer past and to acquire an increasingly venerable history, she also participates in the aesthetics of loss characteristic of the contemplation of ruins. The Capitoline She-Wolf is certainly a well-preserved work of art, and we would be hard-pressed to call it a ruin. Yet, throughout her existence, the bronze beast has been closely associated with the condition of ruins. Most visibly, visitors have repeatedly sought to observe the harm purportedly inflicted on the statue's hind legs by the lightning described in Cicero's writings: These “wounds” authenticated the Lupa as ancient because she is damaged and eloquent in her ancient injury.

In 1789, Hester Lynch Piozzi, British diarist and author, informed her readers that “In this repository of wonders, this glorious Campidoglio” she was shown “the very wolf which bears the very mark of the lightning mentioned by Cicero” (Piozzi 385).

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- She-WolfThe Story of a Roman Icon, pp. 63 - 88Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2010