Book contents

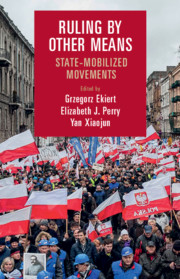

- Ruling by Other Means

- Cambridge Studies in Contentious Politics

- Ruling by Other Means

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Figures

- Tables

- Contributors

- Acknowledgments

- 1 State-Mobilized Movements: A Research Agenda

- 2 Manufactured Ambiguity

- 3 Suppressing Students in the People’s Republic of China

- 4 State-Mobilized Community Development

- 5 Enforcement Networks and Racial Contention in Civil Rights–Era Mississippi

- 6 Social Sources of Counterrevolution

- 7 Occupy Youth!

- 8 State-Mobilized Movements after Annexation of Crimea

- 9 Mirroring Opposition Threats

- 10 Mobilizing against Change

- 11 The Dynamics of State-Mobilized Movements

- 12 State-Mobilized Campaign and the Prodemocracy Movement in Hong Kong, 2013–2015

- 13 The Resurrection of Lei Feng

- Index

- Books in the Series (continued from p.iii)

- References

3 - Suppressing Students in the People’s Republic of China

Proletarian State-Mobilized Movements in 1968 and 1989

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 29 July 2020

- Ruling by Other Means

- Cambridge Studies in Contentious Politics

- Ruling by Other Means

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Figures

- Tables

- Contributors

- Acknowledgments

- 1 State-Mobilized Movements: A Research Agenda

- 2 Manufactured Ambiguity

- 3 Suppressing Students in the People’s Republic of China

- 4 State-Mobilized Community Development

- 5 Enforcement Networks and Racial Contention in Civil Rights–Era Mississippi

- 6 Social Sources of Counterrevolution

- 7 Occupy Youth!

- 8 State-Mobilized Movements after Annexation of Crimea

- 9 Mirroring Opposition Threats

- 10 Mobilizing against Change

- 11 The Dynamics of State-Mobilized Movements

- 12 State-Mobilized Campaign and the Prodemocracy Movement in Hong Kong, 2013–2015

- 13 The Resurrection of Lei Feng

- Index

- Books in the Series (continued from p.iii)

- References

Summary

State-mobilized movements (SMMs) can be found among all regime types, democratic and nondemocratic alike. But certain types of regimes are more likely to generate certain types of SMMs. Communist regimes are partial to proletarian SMMs, calling on the moral authority of the “vanguard revolutionary class” to defuse challenges from other social elements at moments of internal crisis. In light of the signal importance of the proletariat in Marxist-Leninist ideology, it is not surprising that regimes controlled by communist parties should elect to enlist the participation of loyal workers in countermovements intended to delegitimize and demobilize threatening opposition. Unlike repression by the police or military, proletarian action has the advantage of political correctness. Relying on squadrons of workers to neutralize other social forces also promises more pragmatic advantages, especially when the social movement in question is composed largely of students. In responding to contention on the part of idealistic students, whose movements typically generate widespread sympathy among urban residents, intervention by unarmed workers is less apt to alienate the populace than naked military suppression.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Ruling by Other MeansState-Mobilized Movements, pp. 57 - 85Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2020

References

- 1

- Cited by