Introduction

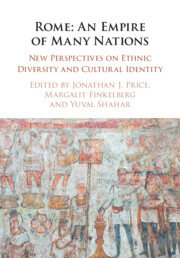

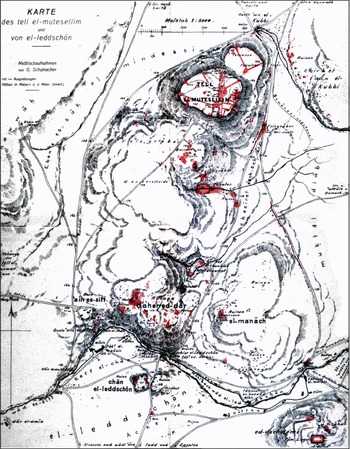

The Roman army in the eastern Roman Empire has been discussed extensively, including its military organization, camps, interaction with the local civilian population and policing and security actions.Footnote 1 Historical sources and epigraphical and archaeological finds attest to the presence of the Roman army in the Land of Israel, in Provincia Syria-Palaestina,Footnote 2 including the Roman legionary base of the Tenth Legion in Jerusalem.Footnote 3 With regard to the Roman military presence and the establishment of the Roman base at Legio-Kefar ‘Othnay, Isaac and Roll argued that the soldiers of Legio II Traiana, who also built roads in the area between the legionary base and Akko-Ptolemais,Footnote 4 arrived first, and those of Legio VI Ferrata replaced them slightly thereafter.Footnote 5 Inscriptions found in Israel reveal that soldiers of both legions built the aqueducts to Caesarea.Footnote 6 The archaeological finds also show the presence of units of the Sixth Legion elsewhere throughout the country, and their bases in or near poleis such as Bet Guvrin-Eleutheropolis,Footnote 7 Samaria-SebasteFootnote 8 and Tel Shalem near Bet She‘an-Scythopolis (Fig. 16.1)Footnote 9 and other sites in Israel where the permanent presence of military units has been proven.Footnote 10

Figure 16.1 Map: Legio-Kefar ‘Othnay and the sites in Palestine that mention Roman military presence, Roman roads and the activities of the soldiers of Legio II Traiana and Legio VI Ferrata (according to Roman Road map, Reference RollRoll 1994).

This evidence has given rise to various theories about the size of the Roman legionary base and the period of time it was occupied by the soldiers of the Sixth Legion until its abandonment.Footnote 11 An archaeological survey in the Legio area proposed that the Roman legionary base at Legio-Kefar ‘Othnay was situated on the northwestern part of the El Manakh hill.Footnote 12 A geophysical survey (2010–11)Footnote 13 and four excavation seasons (2013, 2015, 2017, 2019)Footnote 14 took place on the hill over the past decade, during which architectural remains were uncovered. These support the identification of the legionary base at the site and enable us to relate archaeologically to the history of Roman military presence there in the second–third centuries CE. The findings also allow us to assess the area of the Roman legionary base, whose size resembles Roman legionary bases from the same period known in other parts of the empire.Footnote 15

In this chapter we will survey the historical background of the Roman legionary base at Legio-Kefar ‘Othnay and the small finds such as roof tiles/bricks with Roman military stamps and coins with countermarks as well as Roman weapons.Footnote 16 We will also discuss their contribution to understanding the Roman military presence at Legio-Kefar ‘Othnay.

To begin with, we note that the Latin term castra may be the most suitable term to describe the legionary base. The term translates into English as “camp,” “fort” or “fortress” depending on the usage in various periods. Webster proposed that the term “camp” was used to designate a temporary locale; “fort” was a more permanent station for a single unit, while “fortress” signified a permanent legionary base.Footnote 17 Nevertheless, this chapter will apply the term “legionary base” rather than “fortress” to the Roman legionary base at Legio, because this term attributes administrative characteristics to the site as well as those more typical of a permanent settlement than those associated with a fortified complex. We thank Professor Benjamin Isaac for his assistance in clarifying this issue.

Historical Background

The historical sources about Legio-Kefar ‘Othnay, which were collected by Tsafrir, Di Segni and Green,Footnote 18 reveal evidence of three settlements at the site in the Roman period: a Jewish village (Kefar ‘Othnay), a Roman army base (Legio-Capercotani) and a Roman–Byzantine city (Maximianopolis). In other sources, postdating the Byzantine period, the settlement is mentioned by the Arabic name El Lajjun and in Crusader sources is called La Leyun. These names preserve the name Legio, which in turn stems from the site’s association with the Roman legionary base; it is the name by which the site is still known today.

Flavius Josephus describes Lower Galilee as encompassing the mountainous region only; his description did not include the “Great Plain” (the Jezreel Valley) to the south. The southern boundary of Galilee was marked at Exaloth (Iksal); no Jewish or other settlement is mentioned in the area between Exaloth in the north and Ginae (Jenin) in the south, on the northern border of Samaria.Footnote 19 The Mishnah also indicates that the valley was not included in Jewish Galilee.Footnote 20 By contrast, according to clear Talmudic tradition,Footnote 21 Kefar ‘Othnay marks the southern halachic boundary of Galilee.

The name Kefar ‘Othnay is not known in the Bible, and according to Elitsur, this form originated in onomastica of the Second Temple period.Footnote 22 Talmudic sources mention a locale by the name Kefar ‘Othnay as early as the first generation after the destruction of the Second Temple, at the end of the first century CE.Footnote 23 This is the first mention of Kefar ‘Othnay and the presence of Jews there; later on, Rabban Gamaliel, who was the Patriarch (Nasi) in the second generation after the destruction of the Temple (c. 85–115 CE), visited Kefar ‘Othnay at the end of the first or early second century CE to confirm the divorce of a woman whose two required witnesses were kutim (Samaritans).Footnote 24 Further evidence about the site is found in the testimony of Gamaliel’s son Simon, of the ‘Usha generation’ in the middle of the second century, who presented Kefar ‘Othnay as an example of the produce of Samaritans.Footnote 25

From the sources presented here, we may conclude that a settlement by the name of Kefar ‘Othnay existed as early as the second half of the first century CE and in the second century CE; however, it is unclear from these sources whether Jews continued to live there in the third century and thereafter. The information here indicates that expansion of Jewish settlement in Galilee toward the Jezreel Valley, on the border of Samaritan country, accelerated after the first Jewish revolt (66–73 CE) and necessitated the updating of the halachic “map.”

It is against this backdrop that we should examine the founding and growth of a Jewish village by the name of Kefar ‘Othnay at this historical-geographical juncture and on the seam between the Jewish sphere in Galilee and the Samarian sphere in Samaria.Footnote 26 The mention of this settlement on the border of Galilee on the road from Galilee to Judea, with the same wording used to describe the location of Antipatris – on the border of Judaea and on the road from Judea to GalileeFootnote 27 – bolsters this assumption. Moreover, Rabban Gamaliel’s journeys to Galilee and the mention of his visit to Kefar ‘Othnay are consistent with the description of Kefar ‘Othnay as a point on the southern boundary of Galilee for purposes of the laws governing divorce and as a settlement situated on the main road from Galilee to Judea. Not for nothing did Oppenheimer point out the similarity between the journeys of Rabban Gamaliel of Yavneh and those of Roman rulers of important cities.Footnote 28 It seems that this is another aspect attesting to the location and centrality of settlements on main roads in the Land of Israel in general and the centrality of the settlement at that spot in particular.

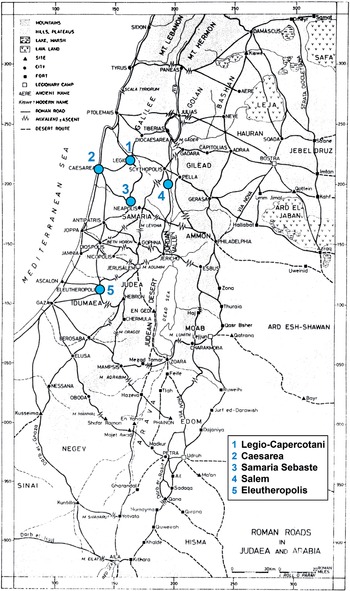

The name Kefar ‘Othnay appears in its Latin form, Caporcotani, as a way station on the Peutinger Map (Fig. 16.2). The final version of that map is dated to the fourth century CE, although scholars agree that its sources concerning the Land of Israel date from the second century CE. The map places Capercotani midway between Caesarea and Scythopolis,Footnote 29 further evidence of its importance in the Roman imperial road network. The settlement is also mentioned as one of the cities of Galilee in the second-century Geographia by Claudius Ptolemy (καπαρκοτνεῖ).Footnote 30 The appearance of the name on the Peutinger Map and in Geographia shows that the Jewish-Samaritan village (Kefar ‘Othnay) had given its name to the legionary base – Caporcotani/ Caparcotani.Footnote 31 Other than a lone reference in Josephus’ writings to a commander of Legio VI Fretensis who was killed in the Battle of the Bet Ḥoron Ascent during Cestius Gallus’ failed campaign in Judea in 66 CE,Footnote 32 we have no additional evidence, prior to the second century, of the presence in Judea of soldiers of the Sixth Legion, its commanders or headquarters.

Figure 16.2 Peutinger Map – Caporcotani (Legio) along the Roman road between Caesarea and Bet She‘an-Scythopolis (according to Reference WeberWeber 1976, Seg. X.).

The similarity between the name of the Roman legionary base and the name of the mixed Jewish and Samaritan village also emerges from burial inscriptions of soldiers of the Sixth Legion in their place of origin in Asia Minor. The name of the village in Latin appears on the Peutinger Map and in Ptolemy’s Geographia. “Caparcotna” is also attested on inscriptions from Asia Minor.Footnote 33 One of the officers buried in Antioch of Pisidia is Gaius Novius Rusticus, son of Gaius Novius Prescus, who was consul from 165 to 168 CE. Thus, it seems that Gaius Novius served in Kefar ‘Othnay sometime around the mid second century CE,Footnote 34 providing epigraphic confirmation of the historical information.

Furthermore, ancient milestones and inscriptions attest to the location of a legionary base on El Manakh hill at Legio,Footnote 35 showing that the Roman army did indeed reach Legio in the early second century CE.Footnote 36 According to a description by Cassius Dio, dating to the early third century CE, it appears that the Sixth Legion was still encamped in Judea at that time, in addition to the Tenth Legion,Footnote 37 and scholars concur that the Sixth Legion was indeed stationed at Kefar ‘Othnay in Galilee (see next).Footnote 38 The Greek word cast[ron] ([áπó κáστ]ρων), engraved on a milestone found at the third mile from Legio, on the Legio-Scythopolis road, reconstructed by Isaac and Roll as “fortress” or “camp.” According to Isaac and Roll, in the inscription on another milestone along the Roman road from Legio to Diocaesarea (Sepphoris, see next), the word “legion” ([áπó λ]εγεωνος) appears. Both inscriptions probably refer to the legionary base.

Thus, another Roman legion, in addition to the Tenth, was stationed in Provincia Judaea at the second decade of the second century CE. Isaac and Roll suggested that this legion was Legio II Traiana.Footnote 39 The promotion of a provincial governor from the rank of procurator to consul meant that the region received an additional legion. Indeed, an inscription dated to 120 CE was found at Caesarea, honoring Lucius Cossonius Gallus, the twenty-eighth governor of provincial Judaea and consul (approx. 117–18 CE, after the execution of Lusius Quietus). The inscription from Caesarea proves that Lucius Cossonius Gallus was already consul during Trajan’s reign (117 CE).Footnote 40 With regard to Isaac and Roll’s arguments (see aforementioned), it should be noted that Lucius Cossonius Gallus had served only shortly before as the commander of Legio II Traiana.Footnote 41

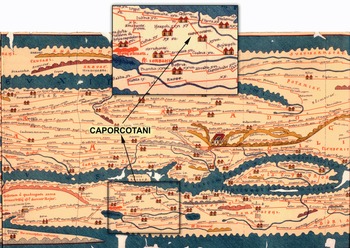

Thus, it would seem that the name Legio became entrenched as the name of the legionary base during the time the Roman legion was there; eventually this name replaced the name Caporcotani/Caparcotani, apparently at the beginning of the third century CE.Footnote 42 The site was also called Legio (λεγεών) by Eusebius in his Onomasticon at the end of the third century CE, where he notes it as a point from which distances to settlements in Galilee were measured (Fig. 16.3).Footnote 43 Because Eusebius’ writings are evidence of the presence of military units in a number of settlements,Footnote 44 including Aila (ʻAqaba) as the base of Legio X Fretensis,Footnote 45 it seems that his failure to mention the name of the unit that was based or present at Legio might indicate that in his time the legionary headquarters was no longer there. As to when the headquarters left Legio, a construction inscription of the Sixth Legion found in Udrukh, ArabiaFootnote 46 apparently attests that at the end of the third century the legion (or at least part of it) had moved eastward.Footnote 47 The absence of the name of the Sixth Legion from the legions posted in Palestine at the beginning of the fifth century CEFootnote 48 underscores the assumption that at that time the headquarters was no longer at Legio-Kefar ‘Othnay. Ritterling claimed that the legion had already left by the time of Alexander Severus (222–35 CE),Footnote 49 and other assessments have been voiced for a later date for the departure of the Sixth Legion from Legio.Footnote 50

Figure 16.3 Map of sites in the Jezreel Valley and its environs showing connections to Legio, according to Eusebius (according to Roman Road Map, TIR 1994; Reference RollRoll 1994; Eusebius, Onomasticon).

Shatzman recently suggested that the small size of the bases in Udrukh and Al Lajjun (in Transjordan)Footnote 51 supports the evidence of the presence of soldiers of Legio VI Ferrata in EgyptFootnote 52 and attests that the legion was split when it was moved from the base in Judea and sent to two provinces, part to Arabia and part to Egypt.Footnote 53 Either way it is likely that by approximately the year 300 the legionary headquarters was no longer stationed at Kefar ‘Othnay.

Hieronymus (342–420 CE), in his Latin translation of Eusebius’ Onomasticon, calls Legio oppido Legionis,Footnote 54 which hints that a key civilian settlement developed at the site after the legion’s departure from Legio or during the last stages of its presence there. The term oppidum indicates a regional administrative settlement center, not necessarily fortified, which under Roman influence gradually became an urban center of the type known in central and Western Europe.Footnote 55 In any case, during the Late Roman period, the name of the place was changed to Maximianopolis. Hence, even if until that time Legio had only the status of a regional settlement center, and assuming that it did not have the status of polis before then, the name change to Maximianopolis indicates that this status was granted to the settlement at that site. Abel suggested that the city was named after the Emperor Maximian Heraclius (286–304 CE).Footnote 56 Other scholars suggested that the name honored the Emperor Maximian Galerius (305 CE) at the latest.Footnote 57 Discussion of the regional urban center that developed at Legio in the Late Roman–early Byzantine period exceeds the boundaries of the matter at hand.

Lajjun, Kefar ‘Othnay and the Legionary Base at Legio

The name Lajjun appears on the Schumacher map (1908) alongside a bridge over Naḥal Qeni (Fig. 16.4).Footnote 58 On Mandate maps,Footnote 59 the name Lajjun is given to the three central villages that existed in the area until the first half of the twentieth century. At the very beginning of scholarly research, the accepted opinion was that the Arabic name preserved the Latin word legio and thus preserved centuries-old traditions going back to the time the Roman legion built its base here.Footnote 60 This toponymic association was known to Eusebius (262–340 CE), author of the Onomasticon,Footnote 61 who notes distances from Legio (Legeon) to a number of settlements in Galilee (Fig. 16.3). As mentioned earlier, based on the distances between known milestones in the area around Legio, Isaac and Roll proposed identifying the location of the camp on El Manakh hill, north of Naḥal Qeni, northwest of the Megiddo Junction and southeast of Kibbutz Megiddo. The hill is mentioned by this name in both the Schumacher map (1908) and the Mandatory map,Footnote 62 and El Manakh according to Sharoni means “place of encampment” or “place of camel encampment” (Reference SharoniSharoni 1987: 1266). This may indicate an area that had previously been used as an encampment and perhaps that the memory of the legionary camp was preserved in the Arabic name of the hill, the way the name Legio-Lajjun (above)Footnote 63 was preserved.

Figure 16.4 Schumacher map (1908), probes and archaeological excavations at Legio.

As noted earlier, in historical sources dated to the mid second century CE, the legionary base was called Caporcotani, after the name of the village (Kefar ‘Othnay) next to which it was established. We identify the rural site excavated within the Megiddo prison compound, south of Naḥal Qeni, as Kefar ‘Othnay. In that excavation we uncovered remains of the rural village and evidence that the population was mixed – Jews, Samaritans and the families of Roman legionaries, some of whom were Christian.Footnote 64 According to the milestones, a Roman legionary base, although established earlier (and called Caporcotani, see previous discussion), was called Legio (“legion”) only after the beginning of the third century, and that was its name until the Roman legion left the site and the Byzantine polis was founded.

Roman military bases and fortifications, as well as Roman roads between main cities (poleis), are known as obvious elements of Roman state-sponsored construction in the Land of Israel.Footnote 65 The connection between the military camp and the nearby road network also manifests itself in the way standard Roman military bases were built. These legionary bases were usually built around an orthogonal network of streets, with the main street running the length of the base, the “headquarters road” or via praetoria, intersected in the center by the main road running its width, the “commanders’ road” or via principalis. At the end of these main streets, in the middle of the base’s walls, four gates were built to provide convenient access to roads leading to and from the base. According to Isaac, the Roman military legionary base in the Land of Israel served as the starting points of roads leading to the imperial road system, and only from the Severan period and onward did six main cities (poleis) in the province serve as starting points for Roman imperial roads.Footnote 66 According to Roll, this network reached its greatest extent during the third century CE.Footnote 67 At that time the legionary base was already situated at Kefar ‘Othnay, but served no more as caput viae.

From previous surveys conducted at the site and as-yet unpublished archaeological excavations,Footnote 68 we may suggest that this was a full-fledged legionary base of the type known in the Western Roman Empire, which we believe covered an area of at most 201.25 dunams (20.125 hectares). No Roman military base of this size from the second to third centuries CE has yet been documented in the eastern Roman Empire.

Roman Military Finds from Legio-Kefar ‘Othnay

Research on the material culture of the Roman army as reflected in archaeological findings in the Land of Israel shows that, in addition to legionary-stamped pottery objects (such as roof tiles, bricks and pipes) and Roman weapons, bread stamps, tableware and amphoras, stone masks, gems and jewelry, architecture, cultic objects and burials all enable us to identify Roman military presence in general.Footnote 69 The findings, of three main types – tiles and bricks with military-legionary stamps, counterstruck coins and weapons identified with the Roman army – will be discussed later. They will assist us in examining Roman military presence at the site.

Stamped Tiles and Bricks

In Jerusalem, where the Tenth Legion was stationed, military stamps, bricks and pipes were uncovered, as was a Roman military workshop, although opinions are divided as to the precise location of the military camp.Footnote 70 This contrasts with the paucity of finds documented so far of military stamps of the legions stationed at Legio. Recently published comparative research, however,Footnote 71 shows major differences in the quantity of military stamps among legionary sites throughout the empire. While in some cases legionary camps have produced a great many finds, excavations of other camps have unearthed no tiles or bricks with military stamps at all. At this stage of the research, therefore, it seems that no great significance should be attached to comparisons of the two sites in this regard.

Nevertheless, a number of tiles and bricks bearing Roman military stamps, or those of Legio VI Ferrata, have been documented from Legio. Reference SchumacherSchumacher (1908: 175) was the first to publish a tile with a Sixth Legion Ferrata stamp (LEG VI FER), which was found east of the theater at Legio. Other stamped tiles were discovered in Schumacher’s excavations of the amphitheater south of the tell and in his excavations at e-Daher Hill.Footnote 72 Sixth Legion-stamped tiles were also found at Tel Ta‘anach, south of Legio,Footnote 73 and an additional tile was found in the hiding complex at Har Hazon.Footnote 74 Adan-Bayewitz reported tiles bearing the Sixth Legion stamp from the excavations at Kefar Ḥananya, on the border of the Upper Galilee, where pottery kilns were also found.Footnote 75 A Sixth Legion-stamped tile was also found in the excavations of the Roman procurator’s palace at Caesarea.Footnote 76 Tiles bearing military stamps have also been documented in private collections and in the possession of communities in the area.Footnote 77 Recently a number of military-stamped tiles were found in a number of archaeological excavations in the Legio area, among them on the edges of the legionary base hill,Footnote 78 in the Megiddo Prison compoundFootnote 79 and in the JVRP excavations of the legionary base.Footnote 80 The findings include stamps of two legions, as well as numerous private stamps and stamps of other units. The latter will not be described here.

Roman Military Stamps of Legio II Traiana

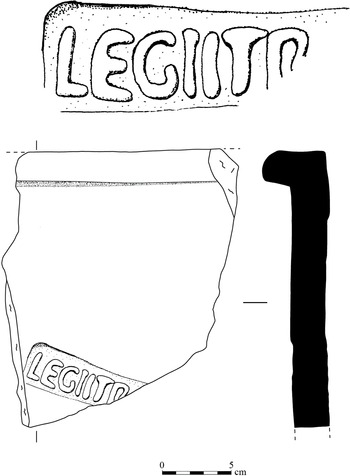

Two stamps were found in excavations at the edges of El Manakh hill, identified as military stamps not of Legio VI Ferrata. In a preliminary report, it was proposed that they be identified as belonging to Legio II Traiana.Footnote 81 On one of the tiles, the following stamped inscription survived: LEGII[], which we propose reconstructing as LEGII[T].

The preliminary assumption, that these were tiles of the Second Legion (Traiana), relies on the fact that this legion is mentioned on the milestone dated to the year 120 CE found along the Roman road from Legio to Sepphoris/Acco.Footnote 82 The stamps on the tile found in the excavations at the edges of the hill are not intact, and we may propose reconstructing them as LEGIII[] or LEGII[]. This would mean the stamps could have belonged either to the Third Legion or the Second Legion (see discussion in the historical overview, n. 39). A new find of tiles of this type in the JVRP excavation of the legionary base,Footnote 83 of more intact stamps of Legio II Traiana, supports this proposal (Fig. 16.5).

Figure 16.5 Tile bearing the stamp of Legio II Traiana, from Legio-Kefar ‘Othnay (JVRP Excavation).

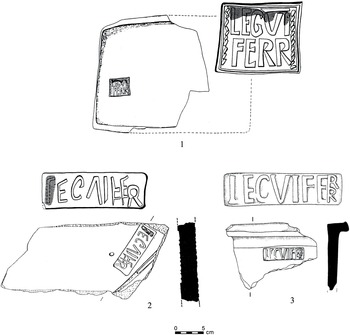

Roman Military Stamps of Legio VI Ferrata

These stamps are divided into six main types. They are categorized typologically, and at this phase of the research it may be assumed that they were stamped at the site during the second to third centuries CE.

1. Well-executed, framed stamp. Top line: LEGVI (with a line above the number VI); bottom line: FERR (Fig. 16.6:1).

2. LEGVIF[ER], in a square frame.

3. LEGVIFE[R], in an elliptical frame.

4. LEGVIFE[R], with a line about the number VI.

5. LEGVIFER, carelessly executed, mostly mirror-stamped (negative; Fig. 16.6.2).

6. Tile with ligature (of the letters ERR) of the word Ferrata (Fig. 16.6.3).

Figure 16.6 Stamps of Legio VI Ferrata stamps from Legio-Kefar ‘Othnay (Tepper 2003).

Although a Roman military pottery kiln has not yet been found in the Legio area, the petrographic tests we conducted on a number of tiles bearing stamps of the two abovementioned legions revealed that they were all made from local clay typical of Naḥal Qeni and the Megiddo area.Footnote 84 This is reasonable testimony to the presence of a workshop at the site, which would have operated to meet the construction needs in and near the legionary base, as shown by similar findings in JerusalemFootnote 85 and elsewhere in the empire.Footnote 86

The issue of whether this workshop operated parallel to a workshop not owned by the Roman army cannot be resolved at this time.Footnote 87 However, we note that the survey of the Legio area and in the excavations of Kefar ‘Othnay revealed clay stands, which are typical of pottery workshop assemblages during the Roman period.Footnote 88 This demonstrates the existence of a local workshop here during the Roman period that would have also produced pottery objects. Another conclusion is that the production of materials for the Roman army at Legio, including bricks and tiles,Footnote 89 should be dated to the first phase of the establishment of the camp at the site, in the second decade of the second century CE.

Countermarked Coins

Countermarked coins with legionary numbers or symbols were minted by the military authorities.Footnote 90 Thus, findings of this type can contribute to the identification of Roman presence at the site, as was also proposed with regard to the Tenth Legion Fretensis in Jerusalem.Footnote 91 Howgego mentioned eleven coins with countermarks of the Sixth Legion (LVIF). The seals in question were overstruck on coins originally minted from 5 BCE to 117 CE. Overstrikes were also found on coins minted in the time of Claudius (41–54 CE), Nero (54–68 CE) and Domitian (81–96 CE), as well as on one coin from the time of Agrippa II (48–95 CE)Footnote 92 from the same series, and Howgego posited that these coins were probably countermarked in Legio after the legion arrived there from Arabia.Footnote 93 In the Legio region survey, more than forty countermarked coins of the Sixth Legion were examined,Footnote 94 most of which were struck over worn coins. Of these, six coins could be identified as having been minted in Antioch, three from the time of Claudius, Domitian and Vespasian (69–79 CE), and two from the Iudaea Capta series, one of the latter from the time of Vespasian.

Our research confirms Howgego’s conclusion that the VI Ferrata countermarks date no later than the second decade of the second century CE. We have found that the Sixth Legion stamps on the coins were divided into three groups: (1) stamps of the LVIF type; (2) stamps similar to the previous group, but with a line above the number VI (see Fig. 16.7); and (3) stamps of the FVI type. Their chronology is a subject for further study.

The letters on all the coins are very finely incised and clear. The average measurements are W: 0.5 mm; H: 2.0–2.5 mm. Of the additional dated countermarked coins, we note one from the time of Domitian and another from the time of Claudius. Interestingly, some of the coins revealed another, rectangular countermark, of a head facing right (see Fig. 16.7), measuring on average 3.5–5.0 mm. Among this type are additional coins that do not feature the legion number; these will be discussed in a separate study. Furthermore, additional coins have recently been found bearing countermarks of the Sixth Legion in the excavations at Kefar ‘Othnay and of the legionary base (not yet published).Footnote 95 Those that can be dated will contribute greatly to the discussion of the characteristics of Roman military minting activities at the legionary base at Legio.

Figure 16.7 Legio, Coin with two countermarks, the first of Legio VI Ferrata, the second of a head facing right (Reference TepperTepper 2014a).

In recent years, coins have been found with the countermark of Legio VI Ferrata at SepphorisFootnote 96 and at Kh. Hammam in eastern Galilee,Footnote 97 two sites that have been identified as Jewish. Although it has been suggested that the coins from Kh. Hammam are part of emergency hoards from the Bar Kokhba Revolt, it is possible that the coins from both sites are evidence of commerce between the legionaries from the base at Legio, or Roman troops throughout Galilee, and civilian settlements in the area of their operations.Footnote 98 The coins from Kh. Hammam might represent a life of peaceful commercial interaction before the violent events. As we know, countermarks of different types, including those of the Sixth Legion, show extensive economic-monetary activity, which included the minting of worn coins with countermarks so as to put them back into circulation. It is reasonable to assume that this activity was carried out by a central authority, apparently in the context of the Sixth Legion at Legio. Furthermore, coins bearing the countermark of the Tenth Legion Fretensis, which were also found at Legio-Kefar ‘Othnay,Footnote 99 enable us to deduce the existence of commerce among legionaries and/or the movement of merchandise between the two legions in the province.

Weapons

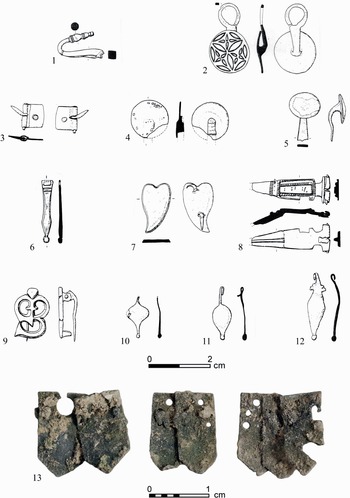

In the Legio area survey and the excavations at El Manakh hill, a number of metal and stone objects were found that were identified as weapons and legionaries’ equipment (Fig. 16.8).Footnote 100 Next, we will discuss a small collection of the metal finds only.

Figure 16.8 Legio, Roman military equipment: 1. Helmet carrying handle; 2–3. Object to be suspended from a sword frog; 4. Belt decoration; 5. Object from a segmented cuirass; 6. Strap terminals; 7. Belt mount; 8–9. Fibula; 10–12. Pendants; 13. Scale armor (Tepper 2003; no. 13 from JVRP excavation).

Helmet carrying handle (Fig. 16.8:1): Such handles were attached at the center of the neck guard. Examples of such handles are known from Masada as well as from Western Europe.Footnote 101 They were also used at the time of the Republic.Footnote 102 Handles of this type also served as mirrors and medicine boxes in Roman times.

Items for suspension on a sword frog (Fig. 16.8:2–3): The Roman sword frog hung from leather strips from a soldier’s belt. The strips were connected to a round, suspended element that was inserted in a slit in the belt. Two items that could not be dated are known from the Legio area. The first (Fig. 16.8:2) is decorated with a typical Eastern-style rosette, which is not previously known on a western weapon. The second (Fig. 16.8:3) was coated with gold, remnants of which can be seen on the round element.

Belt decoration (cingulum, balteus), resembling a tack, with a flat, silver-coated head (Fig. 16.8:4): This item apparently adorned the leather bands that hung from a Roman legionary’s belt.Footnote 103 Parallels are known from many sites in Western Europe (e.g., Vindonissa, Switzerland).Footnote 104

Belt buckle from a segmented cuirass (lorica segmentata: Fig. 16.8:5), used to attach chest and back bands of legionary armor,Footnote 105 dated according to parallels from Britain to the first and second centuries CE.Footnote 106

Strap terminals (Fig. 16.8:6): Droplike, elongated objects attached to the fringes at the end of a Roman legionnaire’s leather belt. Some have associated this item with a horse’s reins.Footnote 107 Many parallels dated to the second and third centuries CE have been found in Romania, Germany, Spain and Britain.Footnote 108

Belt mount (Fig. 16.8:7): Heart-shaped object apparently used as decoration on a legionary’s belt or horse’s bridle. Parallels from the fourth century CE are known from SpainFootnote 109 and Romania.Footnote 110

Fibula (Fig. 16.8:8): Type of strip-bow brooch, dated to the first century CE. Parallels are known from Roman military assemblages in the West (e.g., from Germany).Footnote 111

Fibula in trumpet design (Fig. 16.8:9). The fibula is dated by parallels from Morocco and Germany to the third and fourth centuries CE.Footnote 112 Earlier parallels are dated to the first and early second centuries CE, also documented in Britain.Footnote 113

Pendant (Fig. 16.8:10–12), including a teardrop pendant, which decorated horses’ bridles. Similar pendants, known from Gamla in the Kingdom of Agrippa II as well as from Britain and Romania, are dated to the first and second centuries CE.Footnote 114

Also worthy of joining this assemblage of metal weapons are sixteen pieces of scale armor (lorica squamata) found on the eastern slope of Tel Megiddo.Footnote 115 The form of these scales is typical of scales from the Roman period that are dated to the second and third centuries CE.Footnote 116 Another group of similar scales (Fig. 16.8:13) were found in the JVRP excavations in 2013 in the northern part of the camp.Footnote 117

The variety of weapons and Roman military equipment described here dates from the first to the fourth centuries CE and includes objects that were part of the Roman legionary’s equipment as well as from horses’ bridles, which may also attest to the presence of a cavalry unit at or near the legionary base at Legio. The parallels to these items come also from sites in the eastern empire, but mainly from its western provinces, which is possible evidence of both the source of the manpower and the equipment of the legionaries stationed at the base at Legio-Kefar ‘Othnay.

Summary

The evidence of Roman military presence in the area of Legio-Kefar ‘Othnay found in roof tiles, coins and weapons augments the growing architectural-archaeological testimony from the excavation project of the legionary base at Legio-Kefar ‘Othnay. Although we have not extended discussion to the detailed results of the excavations at the base, we can already propose that this was a legionary base whose plan and dimensions show that it was built in full Roman legionary style as it is known in the western Roman Empire.

The abovementioned military stamps on roof tiles and bricks reinforce the assessment that, during the lifetime of the base, two legions were stationed there, Legio II Traiana and Legio VI Ferrata, and they support Roll and Isaac’s theory that Legio II Traiana was first to arrive there, followed by Legio VI Ferrata. We concur with their proposal that Legio II Traiana was there for only a short time, and that the Sixth Legion, which settled there only after the Second abandoned it, remained there until it was sent to Arabia at the end of the third century CE or the beginning of the fourth century CE, at the latest.

The weapons described here show the presence of Roman legionaries at the site from the end of the first century CE at the earliest and apparently more so only from the early second century until the end of the third century or the early fourth century at the latest. The dating of the evidence revealed by the weapons indicates a Roman military presence at the earliest before the permanent base at Legio was established and at the latest after the departure of most of the Roman forces from the site. This presence may have been in the form of relatively small units, stationed here because of the importance of the location both before and after the permanent base was built or abandoned.

The discovery of counterstruck coins in the Legio survey, the excavations of the base and the adjacent dwelling complex (see subsequent discussion) show commercial ties among the area’s inhabitants, including between the population of Kefar ‘Othnay and the Roman legionaries stationed in the base. The finding of these coins in other archaeological complexes in Galilee that are identified as Jewish settlements underscores this theory and expands the understanding of the legionary sphere of economic influence to additional areas of Galilee.

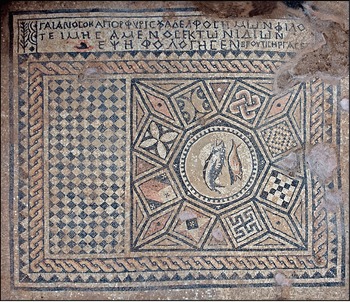

Additional evidence that reveals Roman military presence at the site emerged from a mosaic floor unearthed in the Megiddo Prison compound in salvage excavations by the Israel Antiquities Authority (2003–8; Fig. 16.9).Footnote 118 A wealthy dwelling uncovered at the edge of Kefar ‘Othnay revealed three inscriptions in Greek, one of which was dedicated to “the God Jesus Christ.” Another inscription notes that a Roman centurion generously donated the floor. His name, Gaianus, indicates a Semitic (Arab) origin. Additional names documented on two bread stamps found in the structure are of Roman centurions; one of these names was apparently of Nabatean origin. We may reasonably posit that these individuals served in Legio VI Ferrata, thus revealing another source of that legion’s manpower. The wealthy structure, whose inhabitants were Christian families of centurions in the Roman army, was built at the beginning of the third century CE and abandoned at the end of that century. We associate its abandonment with the departure of the legion from Legio-Kefar ‘Othnay,Footnote 119 as was also clearly shown from the results of the archaeological excavation in the legionary base (n. 14).

Figure 16.9 Kefar ‘Othnay – the northern panel of the mosaic in the Christian Prayer Hall. The floor was donated by Gaianus, a centurion (Reference Tepper and Di SegniTepper and Di Segni 2006).

The research presented in this chapter will be expanded in the future to include additional, still-unpublished findings from the excavation of the Christian structure in the Megiddo Prison compound and from the excavation of the legionary base (discussed earlier). These additional findings can shed new light on the complex relationship between legionaries and civilians in the eastern provinces in general and in the land of Israel in particular. Thus the current project enables a better understanding of the region of Legio-Kefar ‘Othnay, where a Roman legionary camp coexisted with a civilian settlement, and Roman legionaries and civilians, including pagans, Jews, Samaritans and Christians, lived in close proximity to each other.