While the villas of Campania, especially those of the Bay of Naples, are famous and some well-documented, the southern side of the Sorrentine peninsula overlooking the Bay of Salerno, now commonly known as the Amalfi Coast, was also a venue for maritime villas. Its topography presents high steep limestone cliffs rising to the cordillera of the Monti Lattari at an elevation of 1,400 m. The ravines – deep gorges often with perennial streams –2 and small inlets discouraged land transport and communications except by way of mountain passes and trails, so in antiquity the sea connected the area with the wider region.

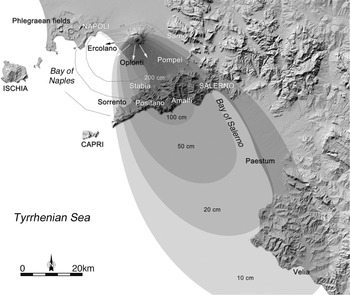

The northeast-southwest axis of the mountain range protects the area and creates a mild microclimate suitable for certain agricultural products (its lemons are famous), but there is little room for agriculture or large settlements. Inhabitants have adopted versatile solutions for the exploitation of the land, ranging from terraced vineyards and orchards on the lower slopes to wider upland grazing pastures. Roman maritime villas are known along this coast at Amalfi and Minori, with the Positano villa being the westernmost. Despite being more than 20 km away from Vesuvius, and in a low position at shore-level below the protection of the mountains to the north, the villa was initially buried under almost 2.00 m of fallout material consisting of ash and pumice in the eruption of 79 CE (Figure 7.1).3 Pyroclastic material entered the buildings through doors and windows, and as it accumulated on the roofs it caused them to collapse. Almost simultaneously, the large quantities of pyroclastic material that fell on the steep slopes of the Lattari Mountains slid downhill, causing lahars or volcanoclastic flows moving at high speed, with devastating consequences for whatever happened to be in their path. The accumulations destroyed the Positano villa: the ground level rose about 20 m in some places and the shoreline advanced, as attested by the identification of a fan-shaped accumulation subsequently dismantled by marine erosion.

The presence of ancient material under the main church of Positano, S. Maria Assunta, had been known from spolia in structures around modern Positano and in archival documents (Figure 7.2 at A). During works to consolidate the bell tower in 1758, ancient remains were identified, and Karl Weber, the engineer of the royal Bourbon administration of Naples and the director of excavations at Pompeii, Herculaneum, and Stabia, was notified.4 On 16 April 1758, Weber started excavating beside the church to a depth of 30 palmi (c. 7.80 m), where he found a “famous old building with a fine white marble mosaic.”5 Weber continued his investigations until the 20th of the month, describing in a short report the architectural features identified: small rooms with poorly preserved wall paintings depicting gryphons, small vessels, “goats” (Capricorn?), and more; two large brick columns covered with vivid red plaster; various masonry water channels; more columns covered in white plaster belonging to a large peristyle with a water basin and a lead pipe, evidently a fountain. Weber also identified a rectangular garden measuring c. 200 palmi (c.52 m) on the long side (Figure 7.2 at C and D).

A: Location of the church of S. Maria Assunta.

A and B: current excavations of the Soprintendenza.

C and D: early excavations (Weber Reference Weber and Ruggiero1758; Mingazzini 1946/Maiuri Reference Maiuri1955).

E – ancient shoreline.

F – Vallone Pozzo stream.

G – limestone bedrock.

Figure 7.2. Positano, plan of town with location of finds and reconstruction of the villa extension.

The sacristan of S. Maria Assunta, one Giuseppe Veniero, reported to Weber that extensive excavations had been carried out in the late 1600s to recover colored marble and architectural pieces, several of which had been sold to the convent of St. Teresa in Naples for funds to update the church’s interior and exterior in the current baroque style. It was thought that the ancient structure had once been a temple; some guides still tell tourists of a “temple of Minerva,” and Weber wrote in his report of “el templo antiguo.”

In the 1920s, new parts of the villa were discovered at the back of a butcher’s shop: some digging revealed the corner of the peristyle identified by Weber in 1758. Several stuccoed columns (their intercolumniations closed off by low walls) came to light, and a plan of the visible portion of the peristyle was published in the early 1930s.6 A devastating flood in 1954 brought to light additional structures belonging to the villa, which Amedeo Maiuri, the director of excavations at Pompeii at the time, rightly identified as part of a villa buried by pyroclastic events in the eruption of 79 CE.7

The First Modern Investigations

Starting in 1999, the Soprintendenza of Salerno has conducted a series of geo-archaeological investigations in order to reconstruct the extent of the archaeological complex buried under the church of S. Maria Assunta, bell tower, and surrounding gardens (Figure 7.2 at A). In 2003, stratigraphic investigations in the crypt of the Church of S. Maria Assunta were carried out. This work was constrained by the small size of the workable area and the need to consolidate the ancient structures and wall paintings while the excavations proceeded. In consequence, only the upper zone of the north wall of a probable triclinium of the villa was uncovered. The excavations were resumed only in May 2015, unearthing the entire north wall and the east wall of the room, down to its simple white mosaic floor framed by bands of black tesserae. Large fragments of a third wall on the west side have been found in situ, while the south side may have opened to a view of the sea or toward a peristyle; a stuccoed column collapsed into the room suggests a peristyle portico or a terrace with a colonnade.

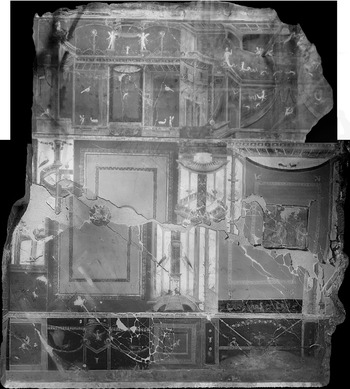

The manner in which the villa was obliterated in 79 CE, with huge quantities of pyroclastic mud mixed with pumice and other volcanic material penetrating into the rooms, has paradoxically allowed for an exceptional state of preservation of the wall paintings. While the pyroclastic flow displaced the upper parts of the walls by over 30 cm southward (toward the sea), the paintings themselves are relatively intact (the gap is visible in the east wall, Figure 7.4).

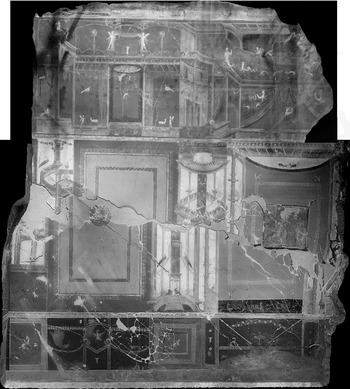

The wall paintings, in the mature Fourth Style, are of high artistic quality and indicate the villa’s opulence (Figures 7.3 and 7.4). The decorative scheme is unusual: There was abundant use of white stucco molded in relief in the upper part of the wall decoration for figures of cupids and fantastic animals. The combination of white stucco relief above and wall painting below has few comparisons in private houses; it was most often used in the vaults of baths and nymphaea.

The blue palette liberally used for the backgrounds of the paintings in the Positano villa also reflects the wealth of the owner: The pigment was expensive and therefore relatively rare in painted walls of private houses. The artists at Positano evidently intended to achieve maximum scenographic effect in the room.

The north wall has further remarkable features: In the upper part of the wall, painted green draperies or curtains “hang” on either side of the central axis of the composition, partially hiding the architectural perspectives behind them (Figure 7.3). The curtains, which have heavy pendant fringes, are held up by cupids rendered in stucco relief, and the cloth itself is decorated with stucco motifs: dolphins and cupids riding on sea monsters. The motif is also depicted on the east wall, but in this case the curtain is almost completely drawn, revealing larger portions of the architectural perspective: a tholos, structures with coffered ceilings supported by columns, views of buildings with balustrades, and half-opened windows and doors.

In the north wall, the upper register depicts a wooden ceiling supported by gilded columns, a complex composition featuring architectural vistas populated by cupids and fantastic figures rendered in stucco, and, in the two side panels, the drapery described in the previous paragraph. The lower register of the north wall is somewhat simpler: large yellow panels interspersed with architectural views, and, in the central panel, two facing peacocks on a garland (Figure 7.3).8 The left and right lower yellow panels are framed, on the top section, by elegant garlands of vine leaves and grapes. Between the upper and lower registers and directly under the architectural views of the upper register, there are small painted pinakes depicting xenia.

The central decoration of the east wall differs from the north one (Figure 7.4). In the middle is a small round temple, a tholos, separating two panels with yellow backgrounds and red frames. At the center of the southern panel, which was being excavated at the time of writing, the yellow background frames a central scene depicting a male figure with a centaur, probably Chiron teaching Apollo how to play the lyre; a third figure could be Dionysus.

The wall decorations are of the highest quality; the colors are rich and vibrant, the palette used ranges from azure-blue to green, from red to yellow. The originality of the composition is also clear when compared to the examples from the Vesuvian area. The Positano villa paintings could have been the work of artists coming from Rome in the ambit of court artists in service at the imperial entourage at Capreae (mod. Capri) (see p. 124) or of local workshops operating for elite patrons in the Sorrento peninsula. Whatever their origins, the work reveals that the artists were up-to-date when it came to current fashions and that their patron had very fine taste and high standards. The artists displayed considerable attention to detail, aptitude for the realization of complex compositions, and attention to the use of color.

In the north side of the room, a piece of furniture appropriate to a triclinium has been found; the elements in wood are preserved as cyneritic deposits, and part of the piece was reinforced internally with an iron frame and had a barred iron door. It was probably an armoire or large strongbox containing stacked bronze vessels, presumably used for banquets in the room.

A test trench dug between the church façade and the bell tower has located another room with a mosaic floor and terracotta tubuli (rectangular hollow tiles applied vertically to jacket the walls) for radiant heating of one of the rooms of the villa’s baths.

At the moment of its destruction, the villa was probably undergoing renovations. A large iron saw found in the triclinium attests work-in-progress, and a test trench opened to the southeast of the church has revealed opus reticulatum walls and a large pile of Neapolitan yellow tufa elements (cubilia) freshly roughed out, to be used in opus reticulatum wall facings. Tufa chips and unfinished elements indicate that the cubilia were being shaped in situ.

Conclusion

Further investigation will be needed to reconstruct the plan of the Positano villa, but the recent excavations and earlier evidence have established that it occupied the entire seafront of what is now the core of Positano’s historical center, from the main church area and gardens of the Hotel Murat to the ancient beachfront located no further than 50 m southward of the S. Maria Assunta church, where restaurants and shops are now located. The complex featured a peristyle with, most probably, a central garden and a fountain (as described by Weber), a bath quarter (the room with terracotta tubuli for radiant heating), and one lavishly decorated room, most probably a triclinium. As with other Roman villae maritimae, there may have been two or more levels. Exactly when the villa was built is not yet clear. Late Fourth-Style decorations are conventionally dated c. 40 to 79 CE, but the walls in opus reticulatum could be much earlier, although there are known issues in trying to use building techniques or wall painting styles as secure dating elements.

Luxury villas existed in Surrentum by early Julio-Claudian times, and possibly earlier: Agrippa Postumus, Augustus’ grandson, was initially confined to one before being exiled to an island.9 Villas on the Sorrento peninsula may have become desirable when Tiberius retired to the island of Capreae in 26 CE: members of the elite may have wished to be only a short boat-trip away from the imperial entourage. On the basis of epigraphic evidence attesting the presence of imperial freedmen from the reign of Claudius (41–54 CE) onward, D’Arms suggested that Claudius may well have built a villa on the south coast of the Sorrento peninsula.10 His suggestion was preceded by an earlier one put forward by Della Corte: On toponomastic grounds (by which current place-names may recall the names of property-owners), the name Positano may be a derivation from Posidetanum (praedium) (“property of Posides”), thus connecting the villa with Posides, a freedman of the emperor Claudius, mentioned in the literary sources for giving his name to famous hot water springs in Baiae and for being a real-estate speculator specializing in luxury villas.11

The Positano villa was clearly a maritime villa fully equal to villas in the Bay of Naples, built and belonging to owners who had special taste in fine wall painting with unusual combinations, composition (paint with stucco relief; the curtains), and colors (blue). The continuing excavations will uncover more of its plan and decoration, and its paradoxically good state of preservation in the face of disastrous destruction – but a different kind of destruction suffered by the towns and villas further north – may well bring to light more of its contents and circumstances.