Samson, Congo, about 25 years old, a height of five feet two inches, having red skin, very large and red eyes, very thick lips and filed teeth, stamped JOUSSAN, the said negro was a cart driver at Le Cap, where he has familiarity, there will be four portugaises to compensate for his capture; Sans-Souci, Mondongue, about 22 years old, a height of five feet, well constituted and marked from smallpox, stamped RAAR, having very black skin; Julien, creole, aged 16 years old, slender, having very black skin and scars on his legs, stamped RAAR; Kepel, creole, brother of Julien, age 12 years old, without a stamp, marked from smallpox, having very black skin and feet a little inside [pigeon-toed]; Ulysse, Mondongue, about 18 years old, of small height, stamped RAAR; Blaise, Arada, age 18 years old, of small height, having marks of his country on his cheeks, stamped RAAR; Mercis, Arada, about 20 years old, height of five feet three inches, reddish skin, pretty looking, having a scar on one leg from an old sickness, stamped RAAR; Nanette, of the nation Monbal, about 45 years old, of small height, without a stamp, a little marked from smallpox, having arched [bowed] legs; Marie, creole, daughter of Nanette, 18 years old, reddish skin, a little marked from smallpox, without a stamp, having arched [bowed] legs, she has given birth about a month ago to a girl, who she brought with her; Marinette, of the nation Moncamba, about 20 years old, of small height, having very black skin, her teeth filed and marks of her country on her face, stamped RAAR; Rose, of the nation Arada, about 20 years old, having very red skin and mark of her country on her face, stamped RAAR. The seven negroes and four nègressses coming from the divisions of Mrs. Raar and L’arouille, planters at Boucan Champagne of Borne, where the negroes have said, on the plantation of M. Millot, of Bas-Borgne and Corail, where they stayed for three months, have fled as maroons from the plantation of M. Jean Cochon at Riviere Laporte, quarter of Plaisance, since the 23rd of last month, with their booty, those who have knowledge are asked to give notice to M. Jean Cochon, owner of the said place, to whom the negroes and nègresses belong, or to Mrs. Milly and Cagnon, merchants at Le Cap. There will be compensation.1

Runaway slave advertisements such as the one transcribed above contain valuable information as well as critical silences about maroons and their intentions. The advertisements are a snapshot of a moment in time and reveal little about the maroons’ past or future beyond the date of publication. This particular advertisement does not indicate what tasks most of the 12 bondspeople performed on the Raar plantation in Borne. It is unclear how and why they migrated to the Millot plantation, or how and why they ended up on the Cochon plantation in Plaisance, from where they left as maroons. Besides brothers Julien and Kepel, and Nanette, her daughter Marie, and Marie’s one-month-old baby girl, the nature of relationships between the absconders is obscure. We do not know how and when they decided to escape together, nor can we elucidate more of their biographical details, such as for how long they had been enslaved in the colony or if they all spoke Kreyol. We cannot know their innermost thoughts, fears, or ambitions. It is not presently possible to find out what happened after their November 23 escape or what happened after the advertisement appeared in Les Affiches américaines on December 15, 1790. They may have been captured, jailed, and returned to Jean Cochon, or they could have remained at large and relocated to another existing maroon community.

Though we do not know for certain the circumstances of Raar plantation runaways’ immediate past and future, the contents of this and similar advertisements reveal insights that help us speculate about enslaved people’s racial and ethnic identities, their inner social world, and their inter-personal relationships. This unlikely group of 12 enslaved people escaped together on November 23, 1790, seemingly after having been sold or leased to a new owner, M. Jean Cochon. Most were branded RAAR, the name of their first owner. There were five women and girls, including Marie’s baby, but most of the fugitives in this case – and those who took part in marronnage overall – were men. One was Kongolese and two were Mondongues of West Central Africa, three were Aradas from the Bight of Benin, four were creoles born in Saint-Domingue, and two were of lesser-known African origins, Monbal and Moncamba. There were two groups of biologically connected individuals. Some were survivors of smallpox and bore scars from other illnesses or injuries; others bore the distinctive cultural markings of their nations. Some were darker skinned, while others had a “reddish” complexion. One was described as having a specialized position, that of a cart driver, and was familiar with Le Cap, where he often worked. Yet, the differences between these bondspeople did not overshadow their shared social conditions and collective decision to engage in marronnage, despite the deadly obstacles they inevitably faced.

How can we understand this small but diverse maroon group as a type of network engaged in collective action? Maroons’ identities and social network ties are lenses through which we can examine “the interaction mechanisms by which individual and sociocultural levels are brought together (Gamson Reference Gamson, Morris and Mueller1992: 71)” during the act of escaping slavery. This chapter relies on protest event content analysis (Koopmans and Rucht Reference Koopmans, Rucht, Klandermans and Staggenborg2002; Hutter Reference Hutter and della Porta2014) of thousands of runaway slave advertisements placed in Les Affiches américaines and other colonial-era newspapers and focuses on two major aspects of how maroons’ socio-cultural realities both shaped and were shaped by their social interactions. I argue in two parts that: (1) racially or ethnically homogenous group escapes reflected and maintained pre-existing collective identities, while racially or ethnically heterogeneous group escapes indicated and helped forge a sense of racial solidarity; and (2) wider networks of resistance were built from runaways’ forms of human capital and their pre-existing social network ties to enslaved people, maroons, and free people of color. These patterns of interaction around identity and solidarity helped shape mobilizing structures during the Haitian Revolution. Moreover, they informed post-independence era modes of identity at the micro- and macro-levels: the formerly enslaved masses organized themselves socially, economically, and religiously around kinship and African ethnicity, while the Haitian state characterized citizenship in racial terms. The formation of these identity- and state-making processes can be traced to the colonial period as enslaved people navigated the boundaries of bondage using their social and human capital.

Micromobilization processes draw on aspects of individuals’ identities and the social network ties that existed prior to mobilization, particularly during exceptionally high-risk collective actions such as marronnage. Network ties can influence multiple aspects of the social construction of mobilization, including an individual’s decision to engage in collective action or not, their assessment of the nature and extent of that participation, their awareness of opportunities to participate, and critical comprehension of the reasons for mobilization (Fantasia Reference Fantasia1988; McAdam Reference McAdam1988; Gamson Reference Gamson, Morris and Mueller1992; Taylor and Whittier Reference Taylor, Whittier, Morris and Mueller1992; Hunt and Benford Reference Hunt, Benford, Snow, Soule and Kriesi2004; Ward Reference Ward2015, Reference Ward2016). Chapter 3 explored ritualist networks that, in enhancing collective consciousness about the unjust nature of racial slavery in Saint-Domingue, used sacred technologies to rectify those imbalances. In addition to ritual spaces, linkages between enslaved people from various birth origins – Saint-Domingue, the Bight of Benin, or West Central Africa for example – were cultivated as people interacted with each other and learned to communicate in the Kreyol language within spheres of labor such as plantation work gangs, in housing quarters and family units, and at weekend markets. These settings foregrounded patterns of interaction in maroon groups by allowing enslaved people to safely query, discuss, plan, and strategize the dynamics of their efforts to self-liberate.

Marronnage was a dangerous endeavor – runaways rarely had access to food or clothing, were chased by hunting dogs and the maréchaussée fugitive slave police, and had to navigate the colony’s complex terrain oftentimes alone. Those who were caught faced punishments such as having limbs cut off, whippings, or being chained or executed. Therefore, taking part in marronnage was not an easy decision, and choosing to do so with others in some ways only heightened the risk of capture. Enslaved people with knowledge of who had escaped, when, why, or where maroons were located could be tortured for that information, or they could be incentivized with money, their freedom, or other material goods to turn in maroons. Trust was of paramount importance when a runaway involved other people in their escape, and their sense of collective identities helped facilitate a “cognitive, moral, and emotional connection with a broader community, category, practice, or institution” (Polletta and Jasper Reference Polletta and Jasper2001: 285). Collective identity in mobilization processes were especially complex in Saint-Domingue. Most of the enslaved population were Africa-born, so the most sensible option for strategizing escape within a group was to turn to one’s “countrymen” who shared linguistic, religious, and cultural identities and affinities. The runaway advertisements’ descriptions of African ethnicities are not much more precise than the labels that derive from slave trading records regarding the specific ethnonyms that Africans would have used, the exact geographic location of their birth, or even the correct port from which they embarked. Still, the ethnonyms in the advertisements give a sense that runaways who were described in similar terms were at most countrywomen and men who may have lived in close proximity or had real connections prior to capture. At a minimum, they were regional neighbors who shared linguistic, religious, or political commonalities, making it likely that these groups mobilized alongside members of their regional background. Findings from content analysis of the Les Affiches advertisements prove most runaway groups were racially or ethnically homogeneous, which further supports the salience of pre-existing collective identities among people of the same racial or ethnic designation in the practice of resistance to “New World” slavery (Thornton Reference Thompson1991; Reis Reference Reis1993; Barcia Reference Barcia2014; Rucker Reference Rucker2015).

While ethnic identification can be an important organizing principle, racial formations can similarly play a role in African Diaspora collective actions (Butler Reference Butler1998). Through geographic proximity, commercial networks, language, and other factors, the conditions of capture and enslavement explicated a “latent potential of ethnicity … even among those who were not consciously so disposed prior to their capture” (Gomez Reference Gomez1998: 7), adding a secondary layer of solidarity building that was at work through heterogeneous group escapes. Constructing a collective identity around Africanness may have been a primary step toward developing a broader sense of blackness. This chapter also aims to make sense of heterogeneous group escapes such as the Raar plantation maroons who were described as Kongo, Mondongue, Monbal, Moncamba, Arada, and Saint-Domingue creole, and explains the broader implications of these types of network formations. New identities and social network ties can form during, and because of, mobilizations like marronnage as disparately identified insurgents developed a sense of solidarity, or shared identification with and loyalty toward each other and a common fate or destiny (Melucci Reference Melucci1989; Gamson Reference Gamson, Morris and Mueller1992; Taylor and Whittier Reference Taylor, Whittier, Morris and Mueller1992; Diani Reference Diani1997; Kuumba and Ajanaku Reference Kuumba and Ajanaku1998; Hunt and Benford Reference Hunt, Benford, Snow, Soule and Kriesi2004). The transAtlantic slave trade, the Code Noir policy on French Caribbean slavery, and colonial plantation regimes forcefully imposed a “flattened” black identity onto the masses of enslaved Africans (Robinson Reference Robinson1983: 99–100; Bennett Reference Bennett2018). However, I argue that maroons and their enslaved or free co-conspirators autonomously socially constructed racial consciousness and racial solidarity through mobilization.

For example, Senegambians and Kongolese captives probably never would have come into contact on the African continent because of the distance between the two regions, thus their only commonalities were their shared survival of the Middle Passage and the status of being enslaved in a foreign environment. As these groups endured colonial structures in the Americas that categorized and exploited people because of their blackness rather than their ethnic, religious, or political origins, inter-ethnic solidarity between enslaved Africans and African descendants became increasingly important (Gomez Reference Gomez1998; Borucki Reference Borucki2015). Moreover, given the sheer size of the Africa-born population in the colony – two-thirds of the enslaved – it is fair to assume that most creoles and mixed-race individuals had direct parentage or other kinship ties to an African, despite claims from early sources that Africans and colony-born creoles were socially distant from each other. There were instances where it was more advantageous for runaways to compose groups that were racially and ethnically heterogenous – such as the Raar maroons. The racial and ethnic groups represented by the Raar maroons might have been able to marshal a wide range of knowledge pools, techniques, and tactics to better strategize escape. But to overcome the boundaries of their birth origins, cultures, religions, and languages, heterogeneous groups of absconders had to develop a certain level of depth in their relationships to establish trust and solidarity. They would have had to cultivate some understanding of their shared positionality of experiencing enslavement based on their blackness, rather than their respective heritages or other aspects of fragmentation among the enslaved population, making racialized experiences the basis for their marronnage.

The colonial newspapers Les Affiches américaines, Gazette de Saint Domingue, and the Courrier Nationale de Saint Domingue published the runaway slave advertisements. Les Affiches (hereafter LAA) was published in Cap Français (Le Cap) and Port-au-Prince beginning in 1766, three years after widespread printing operations were introduced to Saint-Domingue, until 1791, the year the Haitian Revolution uprisings began.2 In the weekly papers, planters advertised sales or rentals of their goods, land, animals, as well as enslaved women and men. Separate listings of advertisements were placed for runaways who escaped enslavement, some for as short as three days, others for over ten years. Planters’ sole intention for placing runaway advertisements was to locate and re-capture fugitives to restore the economic losses of the enslaved people – who as chattel slaves were one of the colony’s foremost forms of capital – and the value of their labor productivity. It was not in planters’ immediate financial interest to provide full narrative accounts of fugitive escapes, since the advertisements themselves cost money to publish; nor was it within the realm of their ontological reality to consider runaways as strategic thinkers who planned their escape. The advertisements contain the implicit and explicit biases of slave owners who viewed enslaved people’s agency as an impossibility, and therefore inscribed into the advertisement texts the impossibility of accessing the full scope of the runaways’ lives. Despite the omissions, deliberate silences, violence, and virulently racist language that are embedded in the texts, there are also elements of enslaved people’s lived reality that can help expand our understanding of their inter-personal relationship dynamics and collective intentionality. To identify and relocate slaves and recoup their lost funds, planters had to provide some modicum of accurate information – however speculative – when placing the advertisements, making them a strong source for demographic representations of the escapee population.

The advertisements present general information including the escapee’s name, age, gender, and birth origin. It was also important for the planter, or plantation lawyer or manager, to identify themselves and provide contact information for where they could be reached and the bounty they were willing to pay as a reward for capture. Typically, the advertisements also included distinctive characteristics such as bodily scarring, the owner’s brand and other physical traits, personality disposition, or the person’s labor skills as a means of locating the escapee. Frequently, the advertisements contain an indication of the duration of time the self-liberated person had been missing, the area from which they had escaped and with whom they fled, and where or with whom they were suspected of hiding. These and other characteristics, such as the maroons’ linguistic skills, are helpful for studying the role of race and ethnicity, gender, and social ties in marronnage. The following section revisits the question of stratification among the enslaved and maroon populations with discussion of the demographics of the 12,857 runaways described in the Les Affiches advertisements.

Fragmentation: race, ethnicity, and gender

Gender

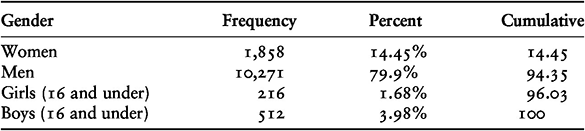

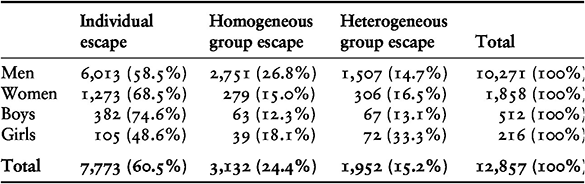

One of the widest imbalances among the maroon population was that of gender. Men over the age of 16 were the majority of runaways, accounting for nearly 80 percent of the 12,857 individuals described in the newspaper advertisements as shown in Table 4.1. Men were the largest proportion of the early transAtlantic slave trade captives and the enslaved population of the French colonies, but sex ratios were almost even leading up to the Haitian Revolution.3 Still, men were slightly over-represented in the distribution of the enslaved population, accounting for their high proportion among runaways. Men were also more likely to occupy artisanal labor positions that allowed them a certain amount of latitude during the workday. As will be discussed below, coopers, carpenters, shoemakers, fishermen, and other artisans ran errands, apprenticed and were leased by their owner to other plantations, or hired themselves out to earn their own money. As such, men could take advantage of quotidian labor-related tasks to escape without immediate detection. African men probably adapted to acquiring these proto-industrial work skills since, in several African societies, particularly the Loango and Angola coast regions, women performed agricultural work. For example, male captives in Portuguese-controlled Angola rejected agriculture-based slavery – seeing it as demeaning to their masculinity – and fled in response.4 Therefore, it is possible that African men who were field workers in Saint-Domingue were more likely to escape as a masculinist rejection of “women’s work.”

Table 4.1. Frequency Distribution of Gender and Age (N = 12,857)

| Gender | Frequency | Percent | Cumulative |

|---|---|---|---|

| Women | 1,858 | 14.45% | 14.45 |

| Men | 10,271 | 79.9% | 94.35 |

| Girls (16 and under) | 216 | 1.68% | 96.03 |

| Boys (16 and under) | 512 | 3.98% | 100 |

Conversely, enslaved African women in Saint-Domingue were over-represented as field workers and performed the most physically taxing jobs. While creole and mixed-race enslaved women were likely to be artisanal laborers or were found in the domestic sphere, most Africa-born women were under strict surveillance throughout the workday and therefore did not have as much flexibility to travel beyond the plantation.5 There is a disproportionately low number of women reflected in the runaway advertisements, with women representing only 14.45 percent of the reported runaways. Some historians (Gautier Reference Gautier1985; Fick Reference Fick1990; Moitt Reference Moitt2001; Thompson Reference Thompson2006; Blackburn Reference Blackburn2011) postulate that women were more likely to commit petit marronnage, and though planters did not report these missing cases, women acted as bridges between plantations and communities of escaped people and helped to create the mobilization structures necessary for organizing the Haitian Revolution. Conventional ideas about women’s marronnage also suggest that child-rearing responsibilities precluded many of them from taking the risk involved with escape on a permanent basis. Additionally, creole women were more likely than their male counterparts to receive legal manumission, often resulting from bearing a child biologically connected to white slavers due to mostly involuntary sexual relations. But, when we explore women’s resistance and look at their escape strategies, we see that some women did commit marronnage and at times did so with their children in tow. Some women who took flight were accompanied by young children, and 30 women escaped while with child.

We do not know much about the experience of childhood in Saint-Domingue, however it is important to note that black children below the age of 16 were enslaved and escaped bondage, either with a parent or another adult but sometimes alone. Gender patterns in marronnage among children generally mirrored those of adults (Table 4.1). Male children escaped over twice as often as female children: 3.98 percent compared to 1.68 percent, respectively. Plantation inventories show that boys tended to begin work around age eight, tending animals, working as domestics, or working in the field. Girls worked as nurses, domestics, and field hands.6 But Moreau de Saint-Méry observed that creole girls tended to have children at an early age, as young as 11 or 13, which temporarily delayed their entry into the workforce until after their first child was born.7 Adult women were slightly more likely than men to run away in a heterogeneous maroon group – 16.5 percent compared to 14.7 percent respectively – (Table 4.3) and this is probably because of those who escaped with their children such as the case of Nanette, a Monbal woman, her creole daughter Marie, and one-month old grand-daughter from the Raar plantation.

Thinking about women and children, and the ways in which enslaved women’s reproductive capabilities birthed hereditary racial slavery and hierarchies of racial capitalism (Morgan Reference Morgan2018) can give us an indication of the familial ties that existed between Africans and creoles, including bi-racial mulâtres. When African women’s children fathered by African or creole men were born in the colony, the children were called creole nègres, or blacks, which automatically inserted racial difference between mothers and children where there may have otherwise been a previously existing ethnic similarity. Creole women’s children were similarly black, but when an African or creole woman’s child was a product of coerced sexual encounters with white men, the children were born bi-racial mulâtres. If a creole black woman had a child with a mulâtre, then the child was a two-thirds black griffe. Less common were quarterons, those who were one-quarter black. Therefore, when enslaved women reproduced, their children usually were described as being of a different race. For example, Genevieve, a mulâtresse, who escaped with her daughter Bonne, a quarteronne in March 1786, were categorized differently based on phenotype and parentage.8 Different ethnic or racial identifiers did not inherently signify separation between enslaved people, who were likely related to an African person, given their overwhelming representation among bondspeople. Though women and girls were not highly represented as maroons, their rates of social network ties to family, a plantation-based relationship, or contact with other runaways or free people of color during marronnage were slightly higher than their male counterparts. Thus, enslaved women were indeed deeply connected within the landscape of the enslaved, marooned, and freed people of African descent (Table 4.11). Analysis of marronnage, as this chapter will show, is a way to highlight the nature of those interactions that can begin to complicate the ways we understand how race, ethnicity, and solidarity functioned at the micro-level in a colonial society that was stratified and fragmented by race, gender, occupation, and status, then became an independent nation where blackness was the primary qualifier for citizenship.

Race and Ethnicity

A significant intervention that this chapter, and this book, seeks to make is to disrupt not only the idea that enslaved people were “socially dead” without meaningful interpersonal relationships among other things, but the notion that differentiation and contention characterized and overdetermined the relationships that indeed existed among people of African descent. Early observers and subsequent scholarship regard maroons, slaves, Africans, creoles, mixed-race people, and free people of color as disparate categories of actors who were singularly self-interested and self-segregated. They also describe an internal hierarchy in which creoles occupied a higher status and carried an attitude of superiority toward recently arrived Africans, even though many creoles and mixed-race people shared kinship with older Africans. Moreau de Saint-Méry’s accounts, as well as those from the priest Jean-Baptiste Labat in the early eighteenth century, describe the enslaved population as a group divided by labor tasks and according to skin color, ethnicity, language, and religion. Indeed, the runaway advertisements themselves attest to the vast diversity of the enslaved population, over half of which were adults born in Africa representing over 100 “ethnicities.”9 These ethnic delineations were usually specified in the advertisements, but may not have been entirely historically accurate due to the imprecise nature of European–American slave trading documents. Some African captives were labeled based on the port from which they were shipped like the Capelaous (Cape Lahou), while others were based on broad coastal regions like the “Congos.”10 However inaccurate these labels might be, they represent the closest identifiers presently available to help us understand African origins.

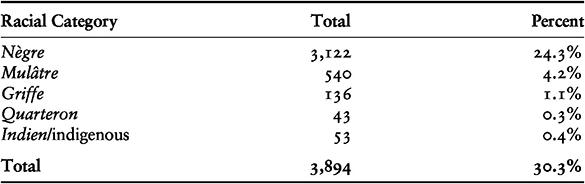

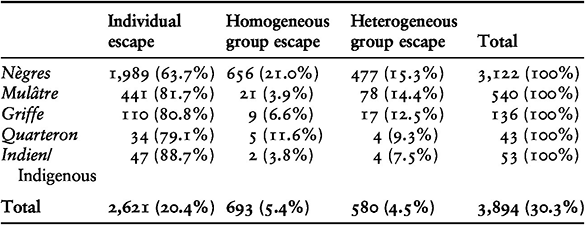

There were 3,122 black creole runaways in the advertisements, so they comprised 24.3 percent of the runaway population (Table 4.2). This is a slight under-representation with respect to their number among enslaved people, which was closer to 33 percent (one-third), likely due to the possibility of gaining freedom through other means. Though a relatively rare occurrence, enslaved creoles could purchase manumission with their labor, and men could join the military and maréchaussée fugitive slave police. Duty in the armed forces was a way for colonial authorities to co-opt marronnage, creating an option for legal emancipation. Similarly, mixed-race people described as mulâtres, griffes, and quarterons were few in number among runaways, since as a group they were more likely to be gens du couleur libres rather than enslaved. However, these findings nuance understandings of Saint-Domingue’s free population of color by demonstrating that not all mixed-race people were privileged by their white fathers’ wealth. The sample was comprised of 4.2 percent mulâtres, 1.1 percent griffes, and 0.3 percent quarterons, meaning over 5 percent of runaways had some degree of white admixture in their lineage. Several advertisements do not describe the runaway’s race or ethnicity at all, but only include the person’s name and the name of the planter. Though we can assume that the runaway was a person of African descent, it is not entirely possible to accurately gauge the person’s racial category – or their geographic origins in Africa – without this information.

Table 4.2. Frequency Distribution of Saint-Domingue-born “Creoles” (N = 12,857)

| Racial Category | Total | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Nègre | 3,122 | 24.3% |

| Mulâtre | 540 | 4.2% |

| Griffe | 136 | 1.1% |

| Quarteron | 43 | 0.3% |

| Indien/indigenous | 53 | 0.4% |

| Total | 3,894 | 30.3% |

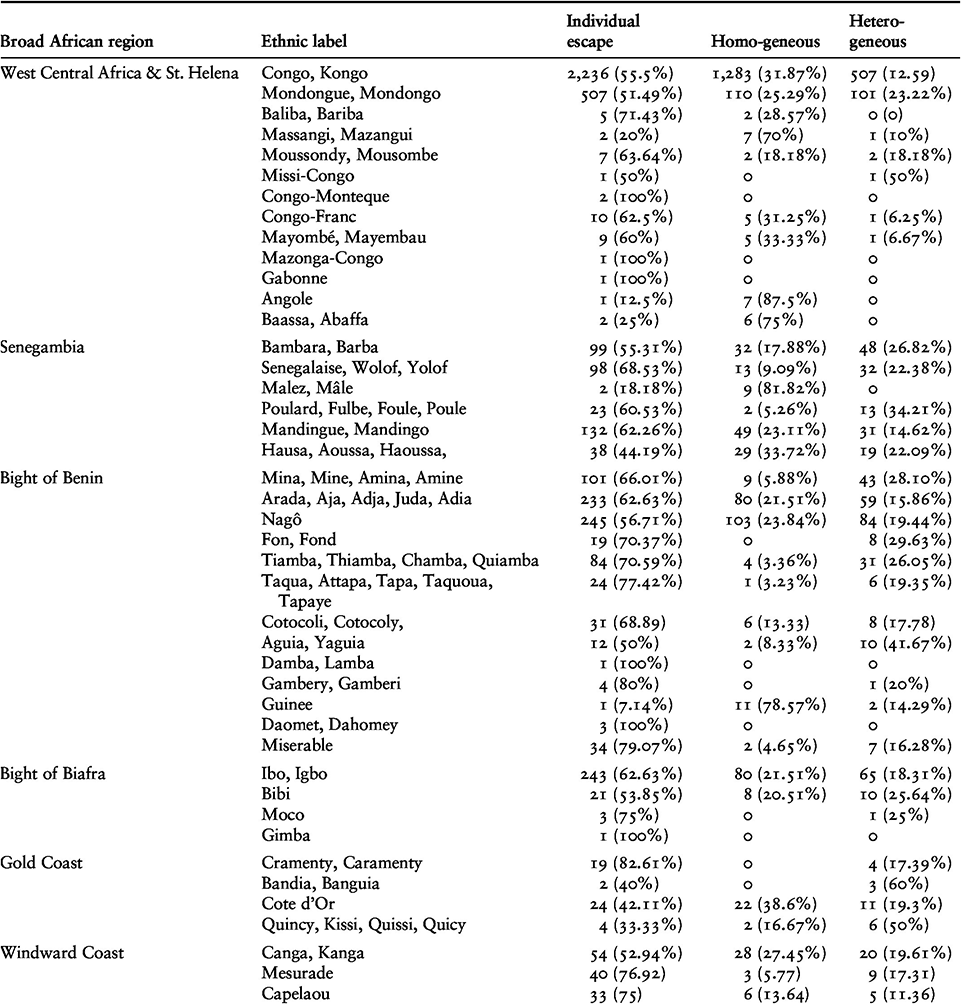

Continent-born Africans comprised approximately 62 percent of the runaway population and well over half of these were West Central Africans, which corroborates other historical data that indicate they were the majority regional group in late eighteenth-century Saint-Domingue. The most numerous of these were generally labelled as “Congo” (hereafter Kongo) without further specification.11 Most French slave trading in this region was at the ports of Malemba and Cabinda on the Loango Coast, while Kongolese captives from Angola, where the Portuguese had long-standing relations and control, were filtered north by the Vili traders.12 But, since the region was comprised of several independently operating kingdoms, such as Loango and KaKongo, there are yet unanswered questions as to the true origins of those described as “Congo” in Saint-Domingue. Despite the mislabeling of most Kongos, there were also significant numbers of West Central Africans like the Mondongues, Mayombés, and Mossoundis from the Loango Coast interior. Only eight ‘Angoles’ and sixteen Congo-Francs were listed, both groups that originated from Angola, providing evidence, albeit thin, of the small presence of Kongo Kingdom captives.13

Although they were the ethnic majority of the enslaved population in the early eighteenth century, by mid-century Bight of Benin natives were a distant second-place African group in Saint-Domingue, comprising 8.9 percent of runaways. Both Nagôs and Aradas were groups conquered by the Dahomey Kingdom, which actively captured and traded slaves along what was referred to as the “Slave Coast.” Though some members of the Dahomey Kingdom did become enslaved due to warfare, only three runaways were described with terminology specifically referencing the kingdom – Dahomet or Dahomey. Nagôs, also referred to as Yorubas in other parts of the Atlantic world, were the largest number of Bight of Benin Africans, with 432 people in the sample. Aradas were the next largest Bight of Benin group, accounting for 372 runaway persons; they were also called by their linguistic grouping of “Fon,” but only 27 Fon absconders appear in the advertisements. There were more Tiambas/Chambas than Fon – 119 – making them an important but less considered component of the Slave Coast population.14 Natives of the Senegambian/Upper Guinea region were the third largest regional group, totalling 5.2 percent of reported runaways. The Mandingues were the highest number of Senegambians, with 212 runaways, followed by 179 Bambaras and 143 Wolofs. Biafrans comprised 3.1 percent of the sample, and most of these were Igbos. The much smaller numbers of Bibi and Moco were Bantu-language speakers who were exported from Biafran ports.15 Most southeastern Africans were from Mozambique, where the French had begun trading in the 1770s.16

Africans from the Gold Coast, Windward Coast, and Sierra Leone were the least represented among runaways – even fewer than southeastern Africans from Madagascar and Mozambique, who numbered 1.3 percent of reported runaways. There were 153 Minas in the sample, making them the largest group of Gold Coast Africans. One hundred and two Cangas were in the sample, making them half of the number of Windward Coast natives. Sierra Leoneans, from a neighboring region to Senegambia, included Sosos, Mendes, and Timbous. Together, Sierra Leoneans made up 0.5 percent of the sample, the smallest number of runaways. Newly imported Africans, whose ethnicity was not yet logged, routinely escaped from ports or plantations before they underwent “seasoning.” Since they were not fully integrated into the plantation system, these runaways were simply referred to as nouveau in the advertisements. Nouveau fugitives would have been conspicuous, having just disembarked a slave ship – perhaps without clothing but with chains binding their necks, feet, and wrists. Still, they made up 3.1 percent of the runaway population, the same as the number of Biafrans represented in the sample.

Saint-Domingue’s enslaved population was diverse according to the ways slave traders and colonial social norms categorized individuals in terms of race, ethnicity, and birthplace. However, these markers of identity were not discrete categories that separated people from one another – for example, one could simultaneously be a mixed-race person or creole born in the Americas to an Africa-born woman. The categories that whites imposed were often unstable and an imprecise reflection of captives’ self-defined identities or their interpersonal relationships. The claims of writers like Moreau de Saint-Méry and Jean-Baptiste Labat, that enslaved creoles segregated themselves from Africans, harken to the false distinctions that late fifteenth- and early sixteenth-century Spanish colonists made between ladinos and bozales to attempt to predict and control one group’s propensity to escape and rebel over the other. These efforts to reify the differences between enslaved creoles and Africans were not based on actual cultural, linguistic, regional, political, or religious differences, but were mechanisms of obfuscating the conditions of enslavement and bondspeople’s inherent opposition to it. As the Spanish colonists found, and as the analysis of runaway advertisements below demonstrates, colony-born bondspeople were not significantly more or less likely to rebel than were Africans of various backgrounds, and in many cases they did so in concert.

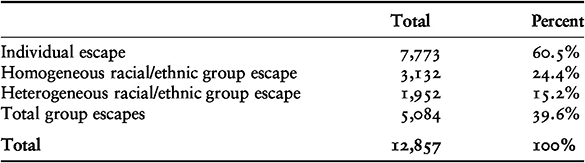

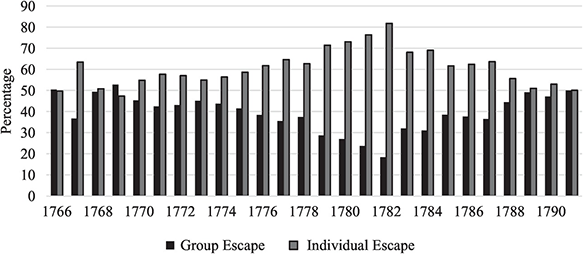

Individual and Group Escapes

Most escapees ran away by themselves, accounting for 60.5 percent of runaways, while a total of nearly 40 percent escaped in a group of two or more people (Table 4.3 and Figure 4.1). Though most fugitives escaped alone, focusing on group escapes helps us understand how oppositional consciousness was operationalized beyond one person’s pursuit of freedom and extended to small-scale groups and bands. Not only were they family units, runaway groups were comprised of shipmates bound together by chains and regional origin, artisanal laborers and members of the same work gangs who fled together, and even strangers with a shared goal of freedom in mind. Homogeneous group escapes, meaning each runaway in the advertisement was described in the same racial or ethnic terms, indicated that a collective identity existed among the cohort; and heterogeneous group escapes, or escapes among runaways from different racial or ethnic backgrounds, demonstrated some sense of racial solidarity between individuals. Cultural and linguistic similarities made it easier for people of similar African heritage to collaborate and escape together, thus homogeneous group escape accounts for 24.4 percent of the sample. It was more difficult for groups comprised of different races and ethnicities to escape together because of cultural and linguistic differences. This can help account for why heterogeneous group escapes were less common, at 15.2 percent.

Table 4.3. Frequency of group escapes (N = 12,857)

| Total | Percent | |

|---|---|---|

| Individual escape | 7,773 | 60.5% |

| Homogeneous racial/ethnic group escape | 3,132 | 24.4% |

| Heterogeneous racial/ethnic group escape | 1,952 | 15.2% |

| Total group escapes | 5,084 | 39.6% |

| Total | 12,857 | 100% |

Figure 4.1. Rates of group and individual escapes over time (N = 12,857)

At a rate of 74.6 percent individual escapes, boys were more likely than girls and adults of both sexes to flee by themselves (Table 4.4). Girls, on the other hand, ran away by themselves less often than anyone else at a 48.6 percent rate of individual escapes; therefore, they fled in groups at the highest rate. More specifically, girls escaped in a homogeneous group 6 percent more often than boys and 3 percent more often than adult women. Girls fled in a heterogeneous group 33 percent of the time, which was more often than anyone else. Since African girls were the minority group in the slave trade and the colony, they would have had a harder time finding someone of a similar background to join in absconding. For example, an eight or nine year old Arada girl named Félicité seems to have fled from Le Cap without an adult in 1768.17 Men were more likely than women or children to escape in homogeneous groups, suggesting men had an easier time identifying and forging relationships with men of a similar background. This is probably because men were the majority in both the slave trade and the colony; indeed, adult women escaped by themselves more than adult men (Table 4.4).

Table 4.4. Chi-square test, group escapes by gender (N = 12,857)

| Individual escape | Homogeneous group escape | Heterogeneous group escape | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | 6,013 (58.5%) | 2,751 (26.8%) | 1,507 (14.7%) | 10,271 (100%) |

| Women | 1,273 (68.5%) | 279 (15.0%) | 306 (16.5%) | 1,858 (100%) |

| Boys | 382 (74.6%) | 63 (12.3%) | 67 (13.1%) | 512 (100%) |

| Girls | 105 (48.6%) | 39 (18.1%) | 72 (33.3%) | 216 (100%) |

| Total | 7,773 (60.5%) | 3,132 (24.4%) | 1,952 (15.2%) | 12,857 (100%) |

Note: p = 0.000.

Saint-Domingue-born and other Atlantic creoles were more likely to escape individually, averaging 78.8 percent and 81.98 percent respectively, while Africans overall had higher levels of group escapes (see Tables 4.4 and 4.9). Few African ethnic groups escaped individually at the same rates as creoles – only “Miserables” (which was possibly an aspersion cast either by their neighbors or French traders),18 Taquas, Capelaous, Cramenties, and Mesurades escaped by themselves over 75 percent of the time (Table 4.6). I have argued elsewhere that Africans were more likely to collaborate in marronnage because they needed to work together to navigate an unfamiliar landspace during their escapes.19 When people did escape in groups, they were more likely to do so with a cohort composed of a cohesive language, culture, race, or ethnicity. However, with time spent in the colony, acquisition of the Kreyol language, and participation in shared rituals, African and creole runaways could form alliances around their shared blackness and enslaved status.

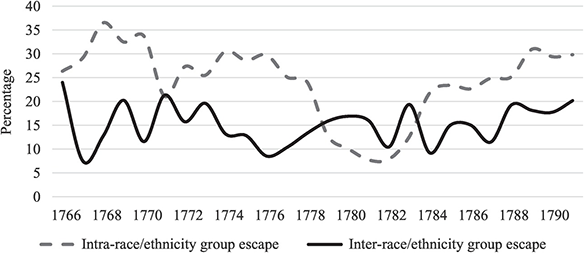

Analysis of homogeneous and heterogeneous group escapes over time helps to reveal observable changes that might indicate growing solidarity among Africans and creoles of diverse backgrounds around a sense of racial identity or whether people clung to their disparate racial or ethnic identities of origin. Homogeneous groups were predominant over heterogeneous groups, reaching their height in 1768, representing 36.5 percent of all escapes then decreasing until the lowest point of 7.7 percent in 1781 and then increasing steadily until 1791 (Figure 4.2). Heterogeneous group escapes were less prevalent overall and were at their highest point in 1766 with 23.9 percent; however, they did outpace homogeneous escapes between the years 1779 and 1784. These years coincide with the decline of group marronnage overall (Figure 4.1), and the American independence-era British blockade on Saint-Domingue’s ports that prevented new slave ships from arriving. Therefore, enslaved people were forced to either escape alone or build new relationships with people of diverse backgrounds due to the lack of newly imported Africans. From 1784, heterogeneous group escapes increased steadily, albeit at a slower pace than homogenous group escapes, until 1791. While shared African ethnicity remained a significant aspect of group escapes, it was also becoming common for runaways to take flight in a group of people from diverse backgrounds. This indicates that a growing sense of racial solidarity was forming within rebellious activities during the pre-revolutionary period.

Figure 4.2. Homogeneous and heterogeneous group escape rates over time (N = 12,857)

Collective Identity: Homogeneous Group Escapes

Homogeneous group escapes among Africans were more common than not. Homogeneous escapes were significantly more common among West Central Africans, especially those labeled with the generic “Kongo” identity – at 31.87 percent – since they were the largest African ethnic group in the colony. Other ethnicities similarly escaped with their kith and kin, probably because they were freshly arrived from the slave ports and were most familiar with each other. Hausas escaped with each other at a high rate as well: 33.72 percent. Nearly 39 percent of Côte d’Or, or Gold Coast, Africans escaped together. Sosos also escaped together at a rate of 29.8 percent; and 27.45 percent of Cangas group escapes were homogenous. This type of identity cohesion may have contributed to developing effective means for escaping, such as: six Nagô men and three Nagô women who escaped in 1786; six “new” Aradas – Hillas, Alexandre, Antoine, Content, Colas, and Tu Me Quitteras – who fled on January 17, 1776; eight “new” Mondongues, who were reported missing for several months in October 1769; the seven Soso (Sierra Leone) runaways in 1787; or the five Igbo absconders in 1788.20

The label of “new” was also used in cases where the runaways’ ethnicity was not yet known because the captives had not yet been fully integrated into the plantation system. The two women and six men described as “new” who escaped the Defontaine plantation at Gonaïves were not assigned names nor were their ethnicities detailed, but we can assume that they were from the same background.21 Runaways whose ethnic identity was unknown because they were new to the colony were most likely to escape together, since they escaped immediately after arrival. Sixty-seven per cent of group escapes among nouveau Africans were with other nouveaus, further demonstrating that shipmate relationships were sustained beyond the ports.

Black creoles had the easiest time finding other creoles to escape with, since 21 percent of creoles’ group escapes were homogeneous. In September 1775, a group of three creole women, Judith, Marie-Jeanne, and Nannette, and six creole men, Apollon, Jerome, Tony, Hercule, Achille, and Polydor, escaped the Fillion plantation at Boucan-Richard in Gros Morne.22 Sully, Thelemaque, Jean-Pierre, Manuel, and Therese were all creoles who left Haut du Cap in February 1786.23 Among Saint-Domingue-born enslaved people, black creole runaways were most numerous, and thus took advantage of those numbers and their cultural dexterity (if they were born to African parents) to escape with other creoles, Africans, or mixed-race individuals (see Tables 4.5 and 4.6).

Table 4.5. Chi-square test, group escapes among Saint-Domingue-born “Creoles” (N = 12,857)

| Individual escape | Homogeneous group escape | Heterogeneous group escape | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nègres | 1,989 (63.7%) | 656 (21.0%) | 477 (15.3%) | 3,122 (100%) |

| Mulâtre | 441 (81.7%) | 21 (3.9%) | 78 (14.4%) | 540 (100%) |

| Griffe | 110 (80.8%) | 9 (6.6%) | 17 (12.5%) | 136 (100%) |

| Quarteron | 34 (79.1%) | 5 (11.6%) | 4 (9.3%) | 43 (100%) |

| Indien/Indigenous | 47 (88.7%) | 2 (3.8%) | 4 (7.5%) | 53 (100%) |

| Total | 2,621 (20.4%) | 693 (5.4%) | 580 (4.5%) | 3,894 (30.3%) |

Note: p = 0.000.

| Broad African region | Ethnic label | Individual escape | Homo-geneous | Hetero-geneous |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| West Central Africa & St. Helena | Congo, Kongo | 2,236 (55.5%) | 1,283 (31.87%) | 507 (12.59) |

| Mondongue, Mondongo | 507 (51.49%) | 110 (25.29%) | 101 (23.22%) | |

| Baliba, Bariba | 5 (71.43%) | 2 (28.57%) | 0 (0) | |

| Massangi, Mazangui | 2 (20%) | 7 (70%) | 1 (10%) | |

| Moussondy, Mousombe | 7 (63.64%) | 2 (18.18%) | 2 (18.18%) | |

| Missi-Congo | 1 (50%) | 0 | 1 (50%) | |

| Congo-Monteque | 2 (100%) | 0 | 0 | |

| Congo-Franc | 10 (62.5%) | 5 (31.25%) | 1 (6.25%) | |

| Mayombé, Mayembau | 9 (60%) | 5 (33.33%) | 1 (6.67%) | |

| Mazonga-Congo | 1 (100%) | 0 | 0 | |

| Gabonne | 1 (100%) | 0 | 0 | |

| Angole | 1 (12.5%) | 7 (87.5%) | 0 | |

| Baassa, Abaffa | 2 (25%) | 6 (75%) | 0 | |

| Senegambia | Bambara, Barba | 99 (55.31%) | 32 (17.88%) | 48 (26.82%) |

| Senegalaise, Wolof, Yolof | 98 (68.53%) | 13 (9.09%) | 32 (22.38%) | |

| Malez, Mâle | 2 (18.18%) | 9 (81.82%) | 0 | |

| Poulard, Fulbe, Foule, Poule | 23 (60.53%) | 2 (5.26%) | 13 (34.21%) | |

| Mandingue, Mandingo | 132 (62.26%) | 49 (23.11%) | 31 (14.62%) | |

| Hausa, Aoussa, Haoussa, | 38 (44.19%) | 29 (33.72%) | 19 (22.09%) | |

| Bight of Benin | Mina, Mine, Amina, Amine | 101 (66.01%) | 9 (5.88%) | 43 (28.10%) |

| Arada, Aja, Adja, Juda, Adia | 233 (62.63%) | 80 (21.51%) | 59 (15.86%) | |

| Nagô | 245 (56.71%) | 103 (23.84%) | 84 (19.44%) | |

| Fon, Fond | 19 (70.37%) | 0 | 8 (29.63%) | |

| Tiamba, Thiamba, Chamba, Quiamba | 84 (70.59%) | 4 (3.36%) | 31 (26.05%) | |

| Taqua, Attapa, Tapa, Taquoua, Tapaye | 24 (77.42%) | 1 (3.23%) | 6 (19.35%) | |

| Cotocoli, Cotocoly, | 31 (68.89) | 6 (13.33) | 8 (17.78) | |

| Aguia, Yaguia | 12 (50%) | 2 (8.33%) | 10 (41.67%) | |

| Damba, Lamba | 1 (100%) | 0 | 0 | |

| Gambery, Gamberi | 4 (80%) | 0 | 1 (20%) | |

| Guinee | 1 (7.14%) | 11 (78.57%) | 2 (14.29%) | |

| Daomet, Dahomey | 3 (100%) | 0 | 0 | |

| Miserable | 34 (79.07%) | 2 (4.65%) | 7 (16.28%) | |

| Bight of Biafra | Ibo, Igbo | 243 (62.63%) | 80 (21.51%) | 65 (18.31%) |

| Bibi | 21 (53.85%) | 8 (20.51%) | 10 (25.64%) | |

| Moco | 3 (75%) | 0 | 1 (25%) | |

| Gimba | 1 (100%) | 0 | 0 | |

| Gold Coast | Cramenty, Caramenty | 19 (82.61%) | 0 | 4 (17.39%) |

| Bandia, Banguia | 2 (40%) | 0 | 3 (60%) | |

| Cote d’Or | 24 (42.11%) | 22 (38.6%) | 11 (19.3%) | |

| Quincy, Kissi, Quissi, Quicy | 4 (33.33%) | 2 (16.67%) | 6 (50%) | |

| Windward Coast | Canga, Kanga | 54 (52.94%) | 28 (27.45%) | 20 (19.61%) |

| Mesurade | 40 (76.92) | 3 (5.77) | 9 (17.31) | |

| Capelaou | 33 (75) | 6 (13.64) | 5 (11.36) | |

| Sierra Leone | Soso, Sosso, Zozeau, Sofo | 25 (43.86) | 17 (29.82) | 15 (26.32) |

| Timbou, Thimbou, Thimbo | 7 (70%) | 2 (20%) | 1 (10%) | |

| Mende | 0 | 0 | 1 (100%) | |

| Southeast Africa & Indian Ocean | Madagascar | 3 (60%) | 2 (40%) | 0 |

| Mozambique, Mozamby | 66 (40.24%) | 82 (50%) | 16 (9.76%) | |

| “Nouveau” | 106 (26.57%) | 270 (67.67%) | 23 (5.76%) | |

| Total | 4,619 (36%) | 2,301 (17.9%) | 1,206 (9.4%) |

Note: p = 0.000.

Racial Solidarity: Heterogeneous Group Escapes

One of the largest group escapes was a heterogeneous band of 22 Africans who escaped the Duquesné plantation at Borgne in October 1789. Three of the 22 were Mondongues: Rampour, Barraquette, and Pantin; eight were Kongos: Abraham, Midi, Nicolas, Theodore, Emeron, Telemaque, and two women named Printemps and Catherine; three were Minas: Pyrame and two women Thisbe and Henriette; five were Igbos: Alexandre, Victor, Hipolite, Agenor, and Luron; one was a Senegambian woman named Agathe; one was a Bambara man named La Garde; and one was a creole woman named Poussiniere.24 Another large group of 19 Africans fled Petite Anse in 1773. Their group included three Kongolese people: Tobie, Lubin, and a woman named Barbe; four Aradas: Blaise, Jean-Baptiste, Timba, and a woman named Grand-Agnes; a Nagô man named Toussaint; and eleven creoles: three women named Louison, Fanchette, and Catherine, and eight men named Foelician, Laurent, Christophe, Jean-Jacques, Joseph, Hubert, Baptiste and Louis.25 These types of heterogeneous group escape were particularly diverse, considering that they were composed of people from vastly different regions. African runaways usually formed groups based on shared regional background, language, or religion. For example, Kongos and Mondongues seem to have been a common combination since they both were KiKongo speakers; as were Nagôs and Aradas, who shared religious commonalities and a common enemy, the Dahomeans. Similarly, Bambaras and “Senegalais” (Senegambians) were a common pairing, such as the group of a group of two Bambaras and two Senegambians who escaped together in December 1783, since they originated from a similar region in Africa and perhaps also shared the Islamic faith.26

Overall, heterogeneous group escapes were more frequent among Africans than African descendant creoles. Bambaras’ heterogeneous escape rate was 26.82 percent, for Poulards (Fulbe or Fulani) it was 34.21 percent, Minas had heterogeneous group escapes 28.1 percent of the time, Thiambas escaped 26.05 percent of the time with others, and Aguias had the highest rates of heterogeneous escapes with 41.67 percent (Table 4.6). None of these groups had substantial numbers, and therefore may have collaborated with others out of necessity, since comrades from the same ethnicity were not readily available. But, black creoles absconded in heterogeneous groups more than other Saint-Domingue-born people at 15.3 percent (Table 4.5). An example of an heterogeneous group escape of Saint-Domingue-born runaways comprised three mulâtre men – François, Baptiste, and Catherine – and six creole counterparts: Haphie, Zabeth, and Cecile, all women, and three men Codio, Gracia, Hypolite.27 In a separate case, three young women, Marguerite, aged 17, Barbe, aged 15, and Marie-Jeanne, aged 16 were all creoles who brought a four-month-old griffe baby with them during their escape from Gros-Morne.28 Another group was composed of two mulâtresses named Marinette and Labonne, two creole women, Marie-Noel and Lalue, and a creole man, S. Pierre, who escaped the Piis property in Dondon in November 1785.29 A fourth example in 1789 shows that a group of 16 absconders was composed of creole women, men, and children, and one Nagô woman.30 Mulâtres had the second-lowest homogeneous group escape rate, at 3.9 percent, and the second-highest heterogeneous group escape, at 14.4 percent. This is likely because mulâtre children were taken with their Africa-born or colony-born creole mothers, or other family members. Similarly, griffes probably had immediate family members of a different race, making their group escapes inherently multi-racial at a rate of 12.5 percent. Quarterons were not very numerous as enslaved people or as runaways, resulting in them escaping by themselves 79.1 percent of the time and in either heterogeneous or homogeneous groups less frequently. “West” and “East” Indians had the highest level of individual escape, at 88.7 percent, and the lowest group escape rates, 11.3 percent altogether, due to their low population numbers.

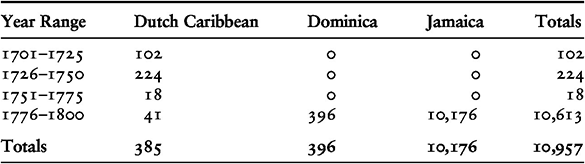

Intra-American Slave Trade Captives in Saint-Domingue

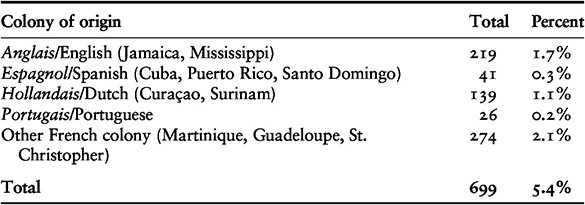

When discussing the notion of an emerging racial solidarity, it is also important to consider the presence of African descendants who were enslaved on other islands within the circum-Caribbean and then re-sold to Saint-Domingue. Julius Scott’s (Reference Scott2018) renowned The Common Wind: Afro-American Communication in the Age of the Haitian Revolution brings attention to the intricate interconnectedness of the Caribbean by way of trade and communication networks. Enslaved and free African descendants who worked as sailors, soldiers, and traders traveled the high seas and transported with them news of events from across the islands. Similar to figures like Olaudah Equiano and Denmark Vesey, exposure to and experience with different imperial structures, plantation regimes, and African ethnic groups helped to cultivate a sense that blackness, not ethnicity, was the basis for enslavement across the Americas. The vast experiences of these “Atlantic creoles” and their observations of black people’s shared circumstances across the Caribbean gave them leadership qualities that could bring together masses from disparate groups. Henry Christophe, who had been part of the siege of Savannah during the American War of Independence and who later became King of northern Haiti in the post-independence era, is said to have been born in either Grenada or Saint Christopher; and “Zamba” Boukman Dutty was brought from Jamaica on an illegal ship in the years before the Revolution. Indeed, English-speakers from Jamaica seem to be the largest enslaved Caribbean group brought to Saint-Domingue. The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database has recently included findings from the intra-American trade, displayed in Table 4.7.

Table 4.7. Disembarkations of enslaved people to Saint-Domingue from the circum-Caribbean, all years31

| Year Range | Dutch Caribbean | Dominica | Jamaica | Totals |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1701–1725 | 102 | 0 | 0 | 102 |

| 1726–1750 | 224 | 0 | 0 | 224 |

| 1751–1775 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 18 |

| 1776–1800 | 41 | 396 | 10,176 | 10,613 |

| Totals | 385 | 396 | 10,176 | 10,957 |

The French royal government banned most of these intra-American trades, so there is an incomplete picture of the full population of enslaved people from across the Caribbean. However, the runaway slave advertisements help to fill in those gaps and demonstrate that captives arrived not only from Jamaica, Dominica, or the Dutch Caribbean, there were also many from Spanish colonies, other French colonies, and North America. Enslaved people brought to Saint-Domingue through the circum-Caribbean trade had experiential knowledge and consciousness that they brought from their perspective locations. They spoke several languages, most commonly English, Spanish, Dutch (and the Dutch creole Papiamento), and French, and some were reading and writing proficiently in those languages. These “creoles” had exposure to information that circulated the Atlantic world via news reporting and interactions at major ports. Not only would they have known of events related to European-Americans, they also would have known about enslaved people’s rebellions that occurred throughout the Caribbean. The largest number of Atlantic-zone runaways were those brought from other French colonies, especially Martinique and Guadeloupe. This is closely followed by the 1.7 percent of escapees who were formerly enslaved in colonies under English rule, mostly Jamaica and including some from Mississippi. At 1.1 percent, the third largest group of Caribbean-born runaways were from Dutch-speaking locations, mainly Curaçao, and a smaller number from Surinam (Table 4.8).

Table 4.8. Frequency distribution of “Atlantic Creoles” (N = 12,857)

| Colony of origin | Total | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Anglais/English (Jamaica, Mississippi) | 219 | 1.7% |

| Espagnol/Spanish (Cuba, Puerto Rico, Santo Domingo) | 41 | 0.3% |

| Hollandais/Dutch (Curaçao, Surinam) | 139 | 1.1% |

| Portugais/Portuguese | 26 | 0.2% |

| Other French colony (Martinique, Guadeloupe, St. Christopher) | 274 | 2.1% |

| Total | 699 | 5.4% |

There also were AmerIndians and East Indians enslaved in Saint-Domingue, making it additionally difficult to ascribe identity in instances of missing data, which accounts for 5 percent of the sample. Fifty-three runaways were described as indigenous Caraïbes or Indiens. These included Joseph, a Caraïbe with “black, straight hair, the face elongated, a fierce look,” who escaped in December 1788; or Jean-Louis, a Caraïbe who escaped with two Nagôs, Jean dit Grand Gozier and Venus, in July 1769.32 An Indien named Andre, a 30-year-old cook who spoke many languages, escaped Le Cap in July 1778; and another named Zephyr, aged 16–17, escaped the same area in late August or early September of 1780.33 Caraïbes were native to the Lesser Antilles and perhaps were captured and enslaved in Saint-Domingue as part of the inter-Caribbean trade.34 The origin of other Indiens, however, is less straightforward. Scholars generally believe that the Taíno population had completely disappeared by the eighteenth century, but this may not be entirely true. Recent developments indicate the Spanish underestimated sixteenth-century census data due to the numbers of Taíno who escaped, oftentimes with Africans, and those who were of mixed heritage.35 Moreau de Saint-Méry witnessed indigenous people’s ritual ceremonies and saw their remains and artistic artifacts throughout the north. However, he used “Indiens Occidentaux” to describe Caraïbes and other indigenous peoples brought from Canada, Louisiana, and Mississippi. Other Indiens were black or dark-skinned sub-continental Asian Indians, or what he called “Indiens Orientaux.”36 For example, there was Zamor, a “nègre indien … creole of Bengale … having freshly cut hair,” who at age 25 escaped the Aubergiste plantation in Mirebalais in August 1783.37 Moreau de Saint-Méry distinguished two types of East Indians: one he perceived as similar to Europeans, with straighter hair and narrow noses. The other he likened to Africans, stating they had shorter, curlier hair and were closer in relation to blacks in Saint-Domingue. Further research is needed on the enslavement of non-Africans in the French colonies, and the possible connections to the African presence in India and the Middle East.38

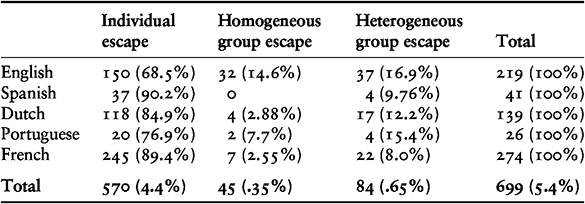

Spanish-speaking runaways escaped by themselves most often; this is perhaps an indication of their small numbers in the colony and lack of contact with others from their language group (Table 4.9). The fugitive migration trail typically tended to go from west to east, so very few escaped from the Spanish colony of Santo Domingo into Saint-Domingue. Yet, in October 1789, the commandant of St. Raphael in Santo Domingo Montenegro reported nine Kongolese men and four women missing.39 Several other “Espagnols” listed in the advertisements were fugitives who were brought from Puerto Rico and Cuba. Small numbers and language barriers did not necessarily preclude non-Saint Dominguans from escaping with others. “Portuguese” (probably Brazilian) captives escaped in heterogeneous groups more often than in homogeneous groups, as did fugitives from Dutch, French, and English colonies. At a rate of 12.2 percent for heterogeneous group escapes, Dutch-speakers were much more likely to run away in a diverse group than a homogenous one. In 1770, a group of six escaped the island in a boat – they were Basile, a mulâtre from Curaçao; Tam, a Kongolese who spoke the Curaçaoan patois “Papimento”; Louis, a creole from Guadeloupe; François from Curaçao; Jean-Baptiste dit Manuel from Curaçao, and Baptiste from Curaçao.40 English colony-born absconders had the highest rate of heterogeneous group escape. On the other hand, English-speaking runaways also escaped with each other the most. French colony runaways escaped alone at the second-highest rate, 89.4 percent, even though they had the linguistic benefit of being able to escape with Saint-Domingue-born runaways. Their French- language skills may also have been to their advantage in passing as free or cultivating relationships with free people of color.

Table 4.9. Chi-square test, group escapes among “Atlantic Creoles” (N = 12,857)

| Individual escape | Homogeneous group escape | Heterogeneous group escape | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| English | 150 (68.5%) | 32 (14.6%) | 37 (16.9%) | 219 (100%) |

| Spanish | 37 (90.2%) | 0 | 4 (9.76%) | 41 (100%) |

| Dutch | 118 (84.9%) | 4 (2.88%) | 17 (12.2%) | 139 (100%) |

| Portuguese | 20 (76.9%) | 2 (7.7%) | 4 (15.4%) | 26 (100%) |

| French | 245 (89.4%) | 7 (2.55%) | 22 (8.0%) | 274 (100%) |

| Total | 570 (4.4%) | 45 (.35%) | 84 (.65%) | 699 (5.4%) |

Note: p = 0.000.

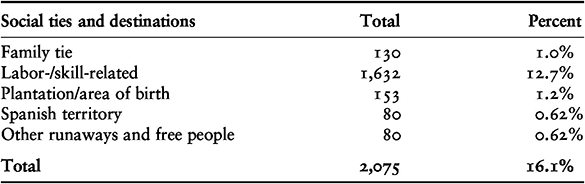

Social Network Ties and Destinations

Alberto Melucci’s Nomads of the Present (1989) clarifies tensions that exist between individuals and groups as they contend with one another, everyday life, and the processes of identity-making within submerged networks. He defines a “submerged network” as a system of small groups, where information and people circulate freely within the network. These networks operate in public view and are transitory, as members may have multiple memberships with limited or temporary involvement. Like ritual free spaces, submerged networks bring to light the importance of shielding these social spaces and relationships from dominating forces within society in order to maneuver with flexibility. The web of maroons, enslaved people, and free people of color that made up submerged networks created new understandings of social circumstances and circulated ideas, resources, as well as strategies and tactics for collective action. An important part of the knowledge shared among the submerged networks of runaways was where one could hide once leaving the plantation. Sunday markets in the major towns like Cap Français were opportunities for blacks – free, enslaved, and runaways alike – to converge and interact, buying and selling food, exchanging services, and sharing information about issues pertinent to their lives, such as achieving freedom. Planters’ advertisements often speculated about where the runaway was going, based on the enslaved person’s known familial ties or the places they were known to frequent to give further alert to other whites in the areas where a runaway might be hiding. These types of location-based relationship ties from formal and informal social spheres like neighborhoods, work, or family are an influential factor in cultivating collective action participation (McAdam Reference McAdam1986; Gould Reference Gould1995; Diani Reference Diani, Diani and McAdam2003). The current section analyzes five types of social ties and destinations that maroons deployed in their freedom journeys (Table 4.10).

Table 4.10. Frequency distribution of social ties and destinations (N = 12,857)

| Social ties and destinations | Total | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Family tie | 130 | 1.0% |

| Labor-/skill-related | 1,632 | 12.7% |

| Plantation/area of birth | 153 | 1.2% |

| Spanish territory | 80 | 0.62% |

| Other runaways and free people | 80 | 0.62% |

| Total | 2,075 | 16.1% |

Besides running away in small-to-large groups, fugitives used their human and social capital to flee from bondage. When possible, enslaved people attempted to connect with family members or other known associates on various plantations. Over time, the enslaved cultivated and established relationships – biological or chosen – with other enslaved people or free people of color. I coded familial ties if the advertisement specifically describes the runaway as having a family member in another location. A second common destination for runaways who were sold and taken elsewhere, but who sought to re-connect with social familiars, was the plantation or parish of their birth. Artisanal labor skills were also an important avenue for escape. Most enslaved Africans and African descendants performed hard labor in the fields of sugar, coffee, and indigo plantations – tilling land, cutting cane, tending to animals, etc. However, larger-scale operations, especially sugar plantations, had a wider array of specialized tasks and positions that men mostly occupied, allowing them more daily flexibility than field hands. Sometimes, owners leased these artisanal laborers to other planters, or the artisans leased themselves out to earn money or their freedom. In these instances, quotidian work patterns of unmonitored travel from one plantation to another, or even between different buildings on the same plantation, would have provided narrow but existing windows of opportunity to slip away without immediate detection. I coded labor- and skill-related destinations if the runaway had access to individuals or spaces beyond the location of their captivity because of their specialized occupation. Another common destination that emerged from the advertisements was the sparsely populated Spanish territory, Santo Domingo, to the east of Saint-Domingue. The imaginary border was the cause of friction between the two colonies, which runaways exploited to their benefit. The ongoing tension over the border will be discussed further in Chapter 6. Finally, I coded free communities to include other maroons and free people of color. In Chapters 6 through 8, I discuss in more depth the small-scale communities of runaways interspersed throughout Saint-Domingue’s numerous mountain chains in hard-to-reach areas, living quietly but at times raiding nearby plantations for provisions. Enslaved people knew of these communities – and sometimes neighborhoods designated for free people of color – and were attracted to these spaces, seeking safe haven.

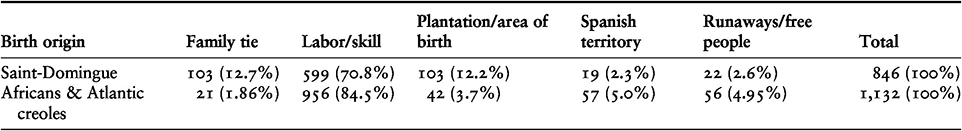

Gender and Birth Origin

Compared to Africans, Saint-Domingue-born African descendants were more than 10 percent likely to use family ties, and more than three times as likely to seek old plantation connections to aid their escape (Table 4.11). Creoles were born and socialized in the colony, had more familial relationships, and had more knowledge of the colony’s landscape. Conventional notions that labor hierarchies followed the logic of the colony’s racial stratum leads many to believe that Saint-Domingue-born creoles were preferred over Africans for artisanal labor positions. However, Africans and Atlantic creoles were more likely to have an artisanal trade than Saint-Dominguans; were more than twice as likely to flee to Santo Domingo; and were more than twice as likely to have been harbored by other maroons or free people of color. Perhaps constant movement and migration were normalized among those who were foreign to Saint-Domingue, having been brought from either Africa or other parts of the Caribbean.

Table 4.11. Social ties and destinations by birth origin (1,978 observations)

| Birth origin | Family tie | Labor/skill | Plantation/area of birth | Spanish territory | Runaways/free people | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saint-Domingue | 103 (12.7%) | 599 (70.8%) | 103 (12.2%) | 19 (2.3%) | 22 (2.6%) | 846 (100%) |

| Africans & Atlantic creoles | 21 (1.86%) | 956 (84.5%) | 42 (3.7%) | 57 (5.0%) | 56 (4.95%) | 1,132 (100%) |

Note: p = 0.000

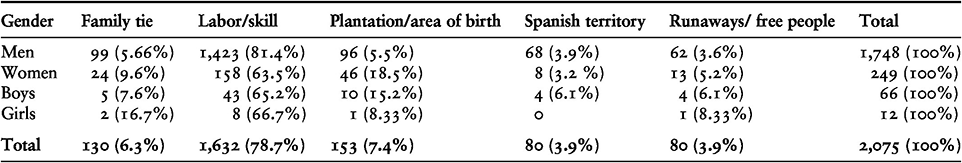

The relationship between gender and social network ties does not prove that women escaped in all-female groups as has been suggested;41 however, it does demonstrate that social networks and mutual aid more generally were an important aspect in women’s patterns of escape (Table 4.12). For example, an Ibo woman named Dauphine escaped as a maroon, taking with her a 13-year-old bi-racial girl named Gabrielle in order to return the child to her mother and siblings.42 When adult women runaways who had some sort of destination in mind stole away from plantations, they were more likely than men to have either a family relationship, a plantation-based relationship, or contact with other runaways or free people of color. Twenty-three year old Reine escaped Port-au-Prince, possibly heading to Grande-Rivière where she had a sister who was free.43 Women fugitives were slightly less likely than men to escape to Santo Domingo, since women relied more on their social capital and relationships to abscond.44 In keeping with plantations’ gendered divisions of labor, men were more likely to use their artisanal labor as an exit strategy, exploiting travel for errands, market days, or going to other plantations as leased labor as a window of opportunity for escape.

Table 4.12. Chi-square test, social ties and destinations by gender and age (2,075 observations)

| Gender | Family tie | Labor/skill | Plantation/area of birth | Spanish territory | Runaways/ free people | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | 99 (5.66%) | 1,423 (81.4%) | 96 (5.5%) | 68 (3.9%) | 62 (3.6%) | 1,748 (100%) |

| Women | 24 (9.6%) | 158 (63.5%) | 46 (18.5%) | 8 (3.2 %) | 13 (5.2%) | 249 (100%) |

| Boys | 5 (7.6%) | 43 (65.2%) | 10 (15.2%) | 4 (6.1%) | 4 (6.1%) | 66 (100%) |

| Girls | 2 (16.7%) | 8 (66.7%) | 1 (8.33%) | 0 | 1 (8.33%) | 12 (100%) |

| Total | 130 (6.3%) | 1,632 (78.7%) | 153 (7.4%) | 80 (3.9%) | 80 (3.9%) | 2,075 (100%) |

Note: p = 0.000.

Labor

Enslaved people performed a variety of tasks associated with the sugar, coffee, and indigo plantation regimes, and they experienced varying levels of physical exertion, punishment, position, and privilege. The vast majority were field hands, but a select few were artisanal trade laborers or otherwise domestic workers who performed tasks that were specialized, which often allowed them to travel beyond their immediate plantation to run errands, or at times even learn to read and/or write a European language. These differentials within the enslaved labor pool might indicate a stratification by occupation that would preclude cooperation between field hands and artisanal laborers or incentivize enslaved artisans from escaping at all. However, over 1,600 maroons, or 12.7 percent of the sample (Table 4.9), were described as having a labor-related skill, and according to the Marronnage dans le Monde Atlantique database, 683 distinct métiers or jobs are found in the advertisements. Seamstresses, midwives, fishermen, hairdressers, shoemakers, carpenters, valets, coopers, sugar boilers, coaches, and commandeurs were just a few of occupations that were considered to have a higher rank in the enslaved labor force. These people would have had relative flexibility in their everyday lives compared to bondspeople, whose labor was confined to the plantation fields (Table 4.9). Though they were still enslaved, artisanal bondspeople in more populated urban areas had contact with people of varying walks of life and saw parts of the colony they may not have otherwise seen. Women tended to be seamstresses, hairdressers, and vendors. Merancienne, a creole woman from Martinique, was a seamstress and laundress who fled Le Cap in September of 1767, and was last seen selling eggs and poultry.45 Another female vendor was 18-year-old Isidore of Kongo, who sold herbs and flowers on the streets of Le Cap and escaped repeatedly in 1770 and 1772.46 Baptiste, a creole man, was both a hairdresser and a violin player who wore a blue vest and black culottes, signifying his relative privilege.47 Even commandeurs, members of the enslaved labor force responsible for maintaining order among the work gangs, escaped their bondage. Scipion, an Arada bondsman, also served as a mason for his owner and ran away for the second time in the fall of 1779.48

Literacy in European languages dominant in the Atlantic world was another skill and form of human capital that facilitated escape. Reading and writing capabilities would have allowed fugitives to legibly forge free papers. Spoken fluency could allow runaways to present themselves to others as free persons of color whose native home was either Saint-Domingue or another colony. For example, runaways speaking Dutch or English could potentially head to a nearby port to board a ship. Thom, a quarteron from Saint Christopher, escaped in July 1788 and was believed to have “liaisons with the English.”49 Marie-Rose, a 14- to 16-year-old girl, spoke very good Dutch and was suspected of hiding out at the coast of Le Cap with a cook who used various alias names.50 An unnamed mulâtre from Guadeloupe spoke French very well and used this knowledge to pass for free in Léogâne.51 Simon, a creole, spoke both French and Spanish, indicating that he may have passed for free in Saint-Domingue or crossed the border into Santo Domingo.52 Besides artisanal labor positions, linguistic skills were one of the only forms of human capital afforded to enslaved people, since most did not have access to formal education or other tools that could be translated to economic or political power. Therefore, runaways made use of the resources most readily available to them in the colonial context, including language and their social relationships.

Family and Plantation Ties

Altogether, runaways who sought out known family ties and old plantations comprised 2.2 percent of the sample (Table 4.9). It was not uncommon for enslaved people to have immediate family members who offered them refuge. Though some women attained manumission through their owners, children of these relationships were not always freed. For example, a mixed-race woman named Magdelaine sought out her free mother, Suzanne, in Cap Français.53 Jean-Baptiste was a creole runaway who had escaped for 15 months, possibly reaching his family of free people of color living in Port-de-Paix, where he was born.54 Other instances show that family members who were still enslaved also provided shelter, even if only for a temporary visit, for their kin. The parents of Phaëton were based on a plantation in Trou when he absconded to find them; and Venus was suspected to have found her mother, who lived in Port-Margot.55 Plantations, especially larger ones with several housing units, could be places of refuge for runaways who were either temporary absentees or lying in wait for a fellow absconder. Père Labat claimed there was a sense of loyalty and cooperation between enslaved people and runaways, detailing the double closets slaves constructed in their cabins to conceal a friend or to hide stolen goods.56 Desirée, a Mondongue, belonged to the Charron plantation in Acul, yet it was suspected that for some time she had been staying at the Caignet plantation, also in Acul.57 Jean-Baptiste, a dark-skinned creole “having traits of a white” had escaped for more than 15 months, and the advertisement states he was born in Port-de-Paix, where nearly all of his family was free.58

Chosen kin ties were also strong, perhaps forged during the Middle Passage, and prompted people to seek out comrades from whom they had been separated. Isidore, a 22-year-old Kongolese stamped T. MILLET and G. ANSE, representing Sieur Millet of the Grand Anse region in the south, stole a canoe that was later found in Petite-Anse in the north. Millet had sold several slaves to the Balan plantation and it was suspected that Isidore was trying to rejoin them.59 For some, being sold to an especially punitive planter could be reason enough to seek out a previous owner who was relatively benevolent. Such “master exchanges” existed in the Loango Coast areas, when mistreated enslaved people offered themselves to new owners.60 As James Sweet has pointed out, a 16- or 17-year-old Kongolese boy named Cupidon had been missing from his owner for six months, and it was believed he was in his old master’s neighborhood; another 17-year-old boy from the Kongo, Julien, escaped heading to Fort Dauphin, hoping to be reclaimed by his first owner.61 Godparentage was another example of fictive kin relationships that supported marronnage, such as the case of Marie-Louise, also called Marie-Magdeleine, who left Eaux de Boynes and may have reached Le Cap where her godmother lived at the women’s religious house.62 Enslaved people used their family relationships to facilitate marronnage; conversely it also stands to reason that they used marronnage to sustain their familial relationships. Despite the practice of slaveowners selling bondspeople to plantations across the colony and away from their familiars, enslaved people and maroons risked their lives to actively nurture their kin relationships and to aid each other in their attempts to self-liberate. Another potential advantage for escapees was having a connection to free people of color or an established maroon community, since these groups could offer protection, housing, and resources like food, clothing, or arms.

Santo Domingo and Free Communities

Interestingly, escaping to Spanish Santo Domingo and seeking out other communities of runaways or free people of color were the least common destinations – each accounting for only 0.62 percent of the sample observations (Table 4.9). The low reporting of runaways fleeing to Santo Domingo and to self-liberated encampments contrasts with several complaints from planters and accounts by former maréchaussée leaders that attest to the presence of absconders both in Saint-Domingue and across the eastern border. Military sources also indicated that Saint-Dominguan runaways settled in Santo Domingo and married locals.63 This could have been the case with Cupidon and Bernard, both Kongolese men who had disappeared ten years before 1787; Jacques, a Mondongue, who was missing for five years; and l’Eveille, an Igbo man missing for two years. The advertisement speculates that they were in Santo Domingo because the four men had not been seen at all since they escaped.64 Others traversed into Santo Domingo to trade with or work for the Spanish, such as Gillot, who was considered very dangerous because he stole horses and mules, then sold them to the Spanish.65 A Mondongue woman named Franchette had been at large for three years and was known for her business dealings with the Spanish.66 French planters’ concerns about runaways to Santo Domingo will be discussed in more depth in Chapter 6.