In Germany and Chile, the market for private health insurance exists alongside and “within” a statutory health insurance system that covers a large majority of the population. Private cover comes in two forms: substitutive, chosen to replace statutory cover, which means that the privately insured do not contribute to this aspect of the social security system (unless statutory health insurance is partly funded through the government budget); and complementary or supplementary, allowing people to “top up” publicly financed benefits. In both countries, the vast majority of the population is covered by statutory health insurance. However, some parts of the population, mostly those who are able to afford it, have the option of choosing between private and statutory coverage. In Germany, the group of people given this choice is limited by regulation, with those allowed to “opt out” of the statutory system having to demonstrate that they have earnings above a threshold. Once they have chosen the private option, the possibility of returning to statutory cover is limited. In Chile, choice of substitutive private cover is also dependent on earnings as a private plan is significantly more expensive than contributions to the statutory system, but there is no fixed threshold for those who wish to opt out. Also, the privately insured in Chile are allowed to re-enter the statutory system at any time, an option that has been intentionally precluded in the German system to reduce the potential for further risk segmentation.

This chapter describes the origins and development of private health insurance in Germany and Chile, providing a comparative assessment of its effects on consumers and the health financing system as a whole. The chapter provides a detailed overview of the market for private health insurance in both countries, followed by a comparative assessment of the impact of private cover in relation to financial protection, equity and efficiency, as well as the aims and effects of recent health insurance reforms in both countries.

Financing and delivery of health care in Germany

Total spending on health care was 11% of gross domestic product in 2015, of which 84% was from public sources (WHO, 2018). About 87% of the population (2015) are members of sickness funds in the statutory health insurance scheme (Gesetzliche Krankenversicherungen, GKV) (Reference SpitzenverbandGKV Spitzenverband, 2016). GKV contributions currently amount to 14.6% of earned income and are equally split between employers and employees. In addition, the government now allows sickness funds to charge an additional income-adjusted premium per enrollee. The government pays contributions for groups such as the long-term unemployed on benefits. Since 2009, GKV contributions have been centrally pooled in a virtual health fund and distributed to sickness funds based on a relatively sophisticated risk-adjustment formula that includes morbidity. Membership of the GKV is compulsory for most people, but certain groups such as civil servants and the self-employed are formally excluded.Footnote 1

About 11% of the population are covered by substitutive private health insurance (Vollversicherung offered by privaten Krankenversicherung, PKVs) (PKV, 2015). Almost half of the population with substitutive private health insurance are recipients of “Beihilfe” (a subsidy) as civil servants, members of the armed services and recipients of social benefits or a veteran pension. Health insurance was only made universally mandatory in January 2009, although coverage was near universal before then (only about 0.2% were uninsured in 2007; Statistisches Reference BundesamtBundesamt, 2008). About 24.3 million people are estimated to have taken out complementary and/or supplementary (Zusatzversicherung) private health insurance in 2014 (PKV, 2015); these voluntary plans are substantially more popular in western states than in eastern states (BMG, 2010).

Health care delivery is organized through a mix of public, private non-profit (typically charitable or church-affiliated) and private for-profit (commercial) providers. Indeed, pluralism of provider ownership is a statutory principle of the health system. In 2015, about 29% of hospitals were publicly owned (for example, by a Land, district or city council), 35% were private non-profit and about 36% were private for-profit (compared with 15% in 1991) (DKG, 2016). In spite of the increase in commercial ownership, almost half of all hospital beds are in public hospitals, compared with 18% in commercial hospitals and 34% in private non-profit hospitals (DKG, 2016). About 41% of physicians, both general practitioners and specialists (constituting about half of office-based physicians), work in ambulatory practices, in single or group practices (based on information from Reference Busse and BlümelBusse & Blümel, 2014). Patients have free choice of provider, irrespective of their insurance status, so that both GKV members and the privately insured can access (almost) any provider.

The history of health insurance in Germany

The origins of private health insurance

Private health insurance has largely developed alongside statutory health insurance. In 1884, statutory health insurance was made mandatory for industrial workers at the national level through legislation passed by the Reichstag in 1883. It was the first national social insurance scheme of its kind. Its origins in voluntary social protection schemes can be traced back to self-help schemes of professional guilds and crafts in the late Middle Ages (Reference Busse and RiesbergBusse & Riesberg, 2004).

From its inception, membership of statutory health insurance was clearly defined and initially limited to industrial workers and their families only. Later in the 20th century, membership was gradually expanded to other occupational groups, including “white-collar” workers (1970) and farmers (1972) (PKV, 2002). All other population groups were formally excluded and could only obtain health cover privately, on a substitutive basis. Private health insurance had existed before the introduction of statutory health insurance legislation, but, in the absence of a legal framework, it is hard to distinguish “social” and “private” initiatives. Arguably, the first “private” insurance scheme was created in 1848 for civil servants of the policing department in Berlin (Prussia) (PKV, 2002).

A first state regulator was created in 1901 to oversee the behaviour of private insurers, the Imperial Supervisory Agency for Private Insurance (Kaiserliches Aufsichtsamt für die Privatversicherung). Private health insurance grew in popularity in the mid-1920s (when the middle classes began to recover from the devaluation crisis), leading to an increase in the number of insurance companies and an expansion of the market. In 1934, a revision of the eligibility criteria for statutory coverFootnote 2 created an additional influx to private health insurance, because those not legally required or entitled to join the GKV were now formally excluded. The Second World War led to the collapse of private health insurance (all insurance, in fact). After the war, private insurers had to recreate their business from scratch in the western part of Germany, while private insurance was prohibited in the Soviet Occupied Zone. A first association of private health insurers was formed in 1946 in the British Occupied Zone (PKV, 2002).

In 1970, mandatory GKV coverage was extended to white-collar workers. The 1970 Act Relating to Health Insurance for Workers (Gesetz betreffend der Krankenversicherung der Arbeiter) also allowed white-collar workers with earnings above a threshold to opt out of GKV or retain membership on a voluntary basis. About 815 000 people switched from private cover to the GKV as a consequence of this change in legislation (PKV, 2002). In 1989, choice of statutory or private cover was extended to all workers with earnings above the threshold (with the exception of civil servants who had always had private cover), a change reflecting the increasingly obsolete distinction between white-collar and blue-collar workers. Private cover was still voluntary for high-income earners, although most of them took out insurance. After the country was (re-)unified in 1990, the “two pillar” health insurance system was expanded to the five eastern states.

Since 1994, individuals over the age of 65 (55 years from 2000) have been legally prevented from returning to the GKV once they have opted for private cover, even if their earnings have fallen below the threshold (€4950 per month in 2018). This measure was introduced to protect sickness funds from further risk segmentation resulting from younger people opting for private cover and rejoining the GKV when they are older and have to pay private premiums in excess of contributions to the GKV. At the same time, private insurers were required to offer a “standard tariff” to ensure that (primarily) olderFootnote 3 privately insured people who were unable to join the GKV because of their age would be able to pay for private cover. The standard tariff covers the range of services covered by the GKV at a maximum price equivalent to the average maximum GKV contribution, irrespective of individual health risk or age.

Recent policy developments

Substitutive private health insurance has been a source of controversy in Germany since the 1990s. The split between statutory and private cover has frequently been criticized as being unfair, because it allows wealthier individuals to opt out of the statutory scheme and pay lower premiums than they would under the statutory scheme (at least as long as they are young and healthy). This has been regarded by many as incompatible with the principle of social solidarity. At the same time, there have been long-standing concerns about financial pressures on the privately insured, as private premiums have increased substantially over time.

Public debate about the future of private health insurance intensified in 2003, following the publication of a report by the Rürup Commission (Kommission für Nachhaltigkeit in der Finanzierung der sozialen Sicherungssysteme). The report discussed options for securing the financial sustainability of the health system and included a proposal to abolish substitutive private health insurance and introduce a universal system of “citizens’ insurance”. An alternative suggestion was to include private health insurance in the national system of risk adjustment. Both proposals were supported by a majority of Social Democrats and Green Party politicians (then forming the federal government), but did not obtain sufficient political support to pass in both chambers of parliament and were eventually abandoned.

Further sustained debate took place following the election of a new coalition government formed by the (conservative) Christian Democrats and the Social Democrats in September 2005. This led to an agreement on a number of reform proposals in February 2007. While most changes – such as the introduction of cost-effectiveness analysis for pharmaceuticals, the creation of a health fund to virtually pool resources across all sickness funds and the merger of GKV associations at the federal level – were directed at the GKV, the reform also had substantial implications for private health insurance. Following the coming into force of the Act to Promote Competition within the GKV (GKV-Wettbewerbsstärkungsgesetz) in January 2009, health insurance, public or private, became mandatory for all residents. The Act stipulated that anyone who was not enrolled in the GKV must take out private health insurance or rejoin the GKV. Private insurers were required to offer a new type of tariff (the so-called basic tariff, which is similar to the standard tariff introduced in 1994) to a wider group of individuals, including people over the age of 55 years, people receiving benefits or a pension, and all those who opted for private cover from January 2009Footnote 4 (see below).

Arguably, the outcome of the 2007 reform reflects two dynamics in contemporary German health policy. Although substitutive private health insurance was repeatedly discussed before the reform, there was no political majority in support of the abolition of the dual health insurance system (often dubbed Zweiklassenmedizin – two-tier medicine – by its critics). In spite of its acknowledged problems (for example. the increase in premiums for older people and the absence of cost control) private health insurance is still the favoured model in large parts of the conservative and liberal (pro-private/pro-corporate) establishment. The dual insurance system is also fiercely defended by the medical profession. Thus the political costs of change are high, creating a propensity to maintain the status quo.

Any changes have largely been introduced at the margins of the system; for example, making people demonstrate earnings above the threshold for 3 years instead of 1 year (introduced in 2007 and revoked in 2010), or the introduction of Wahltarife (optional tariffs) within the GKV, which allow sickness funds to offer a more diversified range of insurance plans.Footnote 5 These new tariffs were at least in part intended to attract or retain those able to choose between GKV and private cover. In contrast, reforms introduced in 2010 by the federal government (then a coalition of Free Democrats and Christian Democrats) aimed to increase the attractiveness of private cover vis-à-vis statutory cover by allowing sickness funds to charge a premium in addition to wage-based contributions. However, a further reform introduced in 2015 under a coalition of Christian Democrats and Social Democrats reduced the contribution rate for people with GKV insurance to 14.6%. Sickness funds can still charge their members an additional fee, but this fee is calculated as a share of income as opposed to being a flat fee.

The succession of recent reforms has led to increasingly stringent regulation of the substitutive private market, which is not uncontested. The PKVs opposed several aspects of the 2007 and earlier reforms, notably rules around the basic tariff, the transferability of ageing reserves and allowing sickness funds to offer voluntary benefits (limited to pharmaceuticals excluded from the statutory package, such as homeopathic drugs). Several private insurers submitted a joint appeal to the Federal Constitutional Court to review the 2007 Act on the grounds that it disadvantaged private subscribers and infringed on the entrepreneurial freedom of insurers (PKV, 2008). The appeal was rejected in June 2009 (Bundesverfassungsgericht, 2009).

Concerns about the future viability of private health insurance were voiced by a PKV working group in 2008 – “Social Security 2020”. In an internal discussion paper (leaked to the press), the group proposed considering the introduction of universal compulsory health insurance, private or public, based on flat-rate premiums independent of age and individual risk. Their concern was that population ageing, in conjunction with regulation, would undermine their ability to attract a sufficient number of young and healthy customers to be able to keep premiums stable. Although the proposal was supported by larger (commercial) insurers, it was fiercely opposed by others (mostly mutual associations) (Reference FrommeFromme, 2008). Some speculated that the days of substitutive private health insurance were numbered, largely due to growing dissatisfaction among the privately insured who faced ever increasing premiums (Zeit online, 2012). More recently, private health insurers have come under increased financial pressure due to low interest rates in the capital market and a rising number of defaulters (Reference Greß, Sagan and ThomsonGreß, 2016).

Overview of the market for private health insurance in Germany

Market structure

Substitutive insurance provides full cover of the costs of health care equivalent (or more) to the benefits covered by statutory health insurance. Complementary or supplementary insurance typically covers the costs of health services that are excluded from the GKV and/or that attract a statutory user charge. In 2014, about 24.3 million people had complementary/supplementary cover, compared with 13.8 million in 2000 (BMG, 2010; PKV, 2015).

Private products are currently offered by 49 insurance companies (PKV, 2015); 24 of these are publicly listed corporations, usually with a wider insurance portfolio; 18 are mutual associations, which specialize in health care; an additional seven insurance companies are listed stock corporations that only offer complementary/supplementary insurance. The market is not highly concentrated – in 2014 the four largest insurance companies had a joint market share of 51% (PKV, 2015). In addition, there are two private funds for railway and postal workers, dating back to the time when both enterprises were (fully) state-owned and their employees were civil servants, and a number of small private insurers operating regionally and only in the complementary market (there were 31 such insurers in 2009 and their combined market share was 0.002%) (PKV, 2010).

Eligibility

Eligibility for substitutive cover is limited to those not mandatorily covered by the GKV, that is, people with earnings above the threshold. Self-employed people are not required to join a sickness fund and usually take out private cover.Footnote 6 The health care costs of civil servants (including teachers and police officers) are mostly covered by the state through “Beihilfe”.Footnote 7 Civil servants only have to cover a small proportion, for which they can buy complementary private cover.

Premiums and policy conditions

Private premiums are based on an assessment of an individual’s risk profile at the time of purchase and adjusted for age, sex and medical history. For employees, the cost of the premium is typically shared with the employer. The employer’s share includes premiums for the insured and any dependants. It is set at 50% of the rate that employers and employees would have to contribute if the employee were in the GKV, and is capped at 50% of the actual insurance premium (PKV, 2009). Dependants are not automatically covered and must pay separate premiums. Some insurers offer group contracts, purchased through employers. Group contracts may offer financial and other advantages, such as lower premiums and waivers of risk assessment and waiting periods (DKV, 2008).

Insurers can reject applications and exclude pre-existing conditions or charge a higher premium to cover them. From 2009, however, they are required to accept any applicant (open enrolment) eligible for the basic tariff and cannot exclude cover of pre-existing conditions for this category of clients. Like the standard tariff, the basic tariff covers services provided under the GKV at a capped premium (€665.29 per month in 2016). If people can demonstrate that they cannot afford the full premium for the basic tariff, the premium will be reduced by 50% and the remainder will be subsidized by the state. If this is still unaffordable, individuals will receive a state subsidy under the social benefits scheme.

Substitutive private cover is for life and operates on a funded basis. Since 2001, insurers have been required to build up ageing reserves to cover age-related increases in costs (and slow the increase of premiums) later in life; reserves are built by charging all clients between the ages of 21 and 60 an additional 10% of all premium payments made.

Benefits

Substitutive private cover typically offers the same comprehensive range of benefits as the GKV. Some specific services may be excluded, such as dental care or treatment in a health resort. From 2009, private plans have had to cover both outpatient (ambulatory) and (non-long-term) inpatient services. Before this, it was possible to choose to be covered for one or the other only. Insurers typically impose a waiting period of 3 months before benefits apply (or 8 months for childbirth, psychotherapy and dental care), but this may be waived if a new customer was previously covered by the GKV (DKV, 2008).

Benefits are mainly provided in cash and may involve cost sharing. Co-insurance is common in dental care and most plans offer deductibles. The deductible amount has been capped at €5000 per year (PKV, 2009). In 2005, about 75% of privately insured individuals (excluding those eligible for Beihilfe) opted for a deductible (25% of those eligible for Beihilfe) (Reference Grabka, Jacobs, Klauber and LeinertGrabka, 2006). Older people are likely to opt for higher deductibles than younger people (Reference Grabka, Jacobs, Klauber and LeinertGrabka, 2006).

The private market offers a wide range of complementary plans, providing reimbursement for services fully or partly excluded from the GKV, such as eyewear, hearing aids and some health checks and diagnostic services (typically excluded or restricted on the grounds of their limited effectiveness or added value). Complementary plans are also available for services that involve statutory user charges, such as dental care, pharmaceuticals. There are also plans offering “top-ups” in hospital, including accommodation in a one- or two-bed ward and treatment by the chief consultant. Despite the enormous variety of plans available, they largely cover combinations of the same services.

Paying providers

Like sickness funds, private insurers are largely bound by collective agreements on provider payment formed by the associations of sickness funds and provider associations (that is, German Hospital Association and Associations of GKV Physicians). In addition, they can form agreements with providers that only treat privately insured patients. Vertical integration with providers is rare and not permitted in some cases (insurers are not allowed to own polyclinics).

Private insurers are generally price takers. In the hospital sector, prices per service are reimbursed based on diagnosis-related groups and prices are identical for statutory and private health insurance. In ambulatory care, prices are based on a list of “basic prices” issued by the Federal Ministry of Health. However, physicians can charge higher fees by multiplying the basic price by a factor set to reflect the level of complexity and time for treatment (for example, a factor of up to 3.5 for personal services rendered by a physician and 1.3 for laboratory services). Physicians are also allowed to bill in excess of these prices, although this requires approval of the insurer before the service is provided (PKV, 2008). Reference WalendzikWaldendzik et al. (2008) have demonstrated that prices for physician services are more than twice as high for the privately insured as for those covered by the GKV. Prices for high-cost pharmaceuticals are now negotiated with pharmaceutical companies for both sickness funds and private insurers. Given the pressure on premiums in recent years, private insurers have shown increased interest in developing better tools to manage care and contain costs (Reference GenettGenett, 2016). However, this is likely to compromise their ability to attract new members.

Unlike sickness funds, private insurers only form direct contractual relationships with subscribers, not with providers. As a result, they have little leverage over providers, many of whom are allowed to charge higher fees for privately insured patients than for GKV members. While insurers routinely check all medical bills submitted by patients, these procedures mainly aim to uncover exaggerated accounts of delivered services or services not covered by the patient’s plan (such as those associated with a pre-existing condition).

Legislation and regulation

Health insurance is heavily regulated through legislation. Social Code Book V (SGB V) regulates all aspect of statutory health insurance, including criteria for eligibility and opting out. It does not regulate private health insurance directly (perhaps with the exception of the basic tariff), but changes in legislation aimed at reforming the GKV often affect private health insurance. Private cover is regulated through a number of laws and ordinances applying to the insurance market in general (for example, insurance contract law) or to private health insurance specifically (for example, provisions for savings). Financial oversight of the private health insurance market is exercised by the Federal Supervisory Office for Financial Services (Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht), an agency of the Ministry of Finance. Developments in the private health insurance sector are also closely observed by the Ministry of Health, although the latter has little direct control over the market. Indeed, interventions typically require changes in legislation and need to be agreed by parliament.

From 2009, customers have been allowed to take the portion of the ageing reserve attributable to the basic tariff with them if they change private insurer (or the entire reserve if they change plan within the same company). This change was introduced to facilitate consumer mobility and promote competition in the private market. Private cover qualifies for tax subsidies. Until recently, a maximum ceiling for tax subsidies applied to all types of insurance, which meant that tax subsidies did not usually provide an incentive to purchase private health insurance. In January 2010, however, a special tax subsidy was applied exclusively to health insurance, including GKV cover.Footnote 8

Financing and delivery of health care in Chile

Health care in Chile is financed through a dual system of statutory health insurance (Fondo Nacional de Salud, FONASA) and private health insurance (Instituciones de Salud Previsional, ISAPRE). Health insurance is mandatory for workers, pensioners and the unemployed (unless they are unable to pay). In 2013, about 76.3% of the population were covered by the statutory scheme and 18.2% had voluntary private cover (Reference SánchezSánchez, 2014; Superintendencia Reference de Saludde Salud, 2015). About 2.95% of the population have access to health care as members of the army (Reference SánchezSánchez, 2014; Superintendencia Reference de Saludde Salud, 2015). Contributions for the statutory scheme are deducted from wages, at a rate of 7% up to a ceiling. People with no or low income are also entitled to join FONASA. Their contributions are covered by the government. Health services funded by FONASA are mainly provided by public providers.

FONASA membership is organized in two tiers. Members of the first tier (A and B, indicating a monthly income below €280 per person) have access to public providers only, organized through 29 local health authorities. Members of the second tier are divided into categories C with an income between €280 and €400 and D with an income above €400, and can choose between public and (accredited and contracted) private providers if they are willing to make a co-payment and buy a pay-as-you-go voucher for additional benefits (originally introduced under the SERMENA system; see below). This is called Modalidad de Libre Eleccion. The privately insured, that is, ISAPRE customers, have access to a wider choice of mainly for-profit private providers. However, some crossover between public and private providers can be observed between both FONASA and ISAPRE members. For example, since 2005, as part of the regimen of Explicit Health Guarantees (Garantías Explícitas en Salud, AUGE), which guarantees a certain set of services for all FONASA members (see below), if the guarantees are not met by public providers, FONASA members can use private providers instead. Also, wealthier FONASA members tend to use the Modalidad de Libre Eleccion and pay-as-you-go vouchers to expand their choice of and access to outpatient services. On the other hand, some underinsured ISAPRE users tend to use public providers for catastrophic events and pay FONASA fees for these.

In terms of provider payment, ISAPRE schemes generally pay private providers on a fee-for-service basis. They usually accept prices prevailing in the market, but in some cases they use lists of preferred providers and negotiate prices with them in bulk (that is, for all providers on the list). FONASA tends to pay public providers according to a centrally defined list of hospital and physician fees and capitation payments for primary care. These fees are much lower than those paid by the ISAPRE schemes (SERNAC, 2011).

Even though vertical integration has been explicitly forbidden by law since 2005,Footnote 9 ISAPRE schemes have increasingly integrated vertically with providers through structures such as health care holdings or integrated care clusters (where the use of certain providers is encouraged through financial hedges). These structures, similar to health care holdings that underlie the health maintenance organizations in the USA (Reference ValenciaValencia, 2012), control about 42% of the private provider market (Reference ValenciaValencia, 2012; Superintendencia Reference de Saludde Salud, 2013). Vertical integration can be viewed as a response to the growing public discontent with escalating health care costs ascribed to the use of fee-for-service as a method of payment in the private subsystem and the resulting excessive profits of private providers (Superintendencia Reference de Saludde Salud, 2013). By merging vertically with providers, ISAPRE insurers can shift costs to the the provider level, avoid increasing premiums at the insurer level and maintain high profits at the level of the health care holding or cluster (Superintendencia Reference de Saludde Salud, 2013). A recent study from the Superintendencia de Salud that compared the prices of four services (caesarean section, normal delivery, cholecystectomy and appendectomy) showed that, in 2016, patients affiliated with vertically integrated private health insurance companies paid on average 19% more for these services than patients with comparably priced plans with similar coverage who were insured in companies that were not vertically integrated (Reference Sandoval and HerreraSandoval & Herrera, 2016).

The history of health insurance in Chile

The first period of statutory health insurance (1880s–1950s)

Throughout most of the 19th century, local authorities and charitable organizations were the main providers of health care, with almost no involvement of the central government in health care delivery. At the end of the century, political pressure to address the health needs of the industrial poor grew, leading, in 1886, to the creation of the Public Relief Commission (Junta de Beneficiencia). This public–private body was mandated to develop a first administrative framework, bringing together various forms of providers, supported by a state subsidy, while maintaining their organizational autonomy. In 1917, renewed political and social pressure led to the creation of the Council of Public Relief (Consejo de Beneficiencia). The Council initiated a national programme to improve health care infrastructure, introducing, among other things, nationwide quality standards in hospitals. By the late 1920s, this network of state-funded hospitals had become the main health care provider.

In 1924, legislation passed by parliament (Law 4.054) established a system of statutory health insurance (the “Cajas” system). Coverage was introduced in three tiers, with separate Cajas for blue-collar workers, white-collar workers and civil servants. The schemes were funded through contributions levied on wage income (initially 3%), contributions from employers (equalling 2% of the employee’s wage) and support from the state (1%). Cajas reimbursed providers on a fee-for-service basis, later changing to a preferred-provider approach, which led to increasing vertical integration of payers and providers.

From 1942, white-collar workers were able to join the National Medical Service for Employees (Servicio Medico Nacional de Empleados, SERMENA). This scheme was created under the umbrella of the Cajas and allowed its members free choice of health care provider. By 1943, 37 Cajas covered around 1.5 million workers and their families (30% of the population) (Reference AlexanderAlexander, 1949). However, the Cajas system left large sections of the population without coverage. Rural peasants and the urban poor in the informal economy (about 33% of the urban labour force in 1952) were excluded (Reference RaczynskiRaczynski, 1994), and dependants were only covered after 1936.

Introduction of the National Health Service (1950s–1970s)

In response to gaps in coverage, in 1952, the populist centre-right administration of President Carlos Ibáñez del Campo merged the Cajas with a wide range of religious, municipal and other public or charitable health care providers to create the National Health Service (Servicio Nacional de Salud, SNS). Mandatory earmarked contributions to the SNS continued to be based on wages (5% for employees, 10% for employers). However, as historical budget deficits required continuous subsidization, transfers from the general government budget became de facto the main source of funding. By 1955, about 1.6 million workers contributed to the SNS, representing 65% of the active population. Individual benefits in terms of the volume of services consumed had risen by approximately 250% in real terms between 1920 and 1950 (Reference ArellanoArellano, 1985).

White-collar workers could still join SERMENA, which had been transformed into a supplementary insurance scheme in 1952. SERMENA members could purchase a pay-as-you-go voucher for additional benefits (including dental, ophthalmological, occupational and mental health services) and choose from a range of providers that were part of the SNS, although not available under the usual arrangement, as well as private providers (Modalidad de Libre Elección). The voucher entitled patients to partial reimbursement for additional services, although many services also involved hefty user charges (Reference 220Vergara-Iturriaga and Martínez-GutiérrezVergara-Iturriaga & Martínez-Gutiérrez 2008). SERMENA was popular with doctors, as it allowed them to earn extra income, and with wealthier people (Reference 217IllanesIllanes, 1993; Reference Horwitz, Bedregal, Padilla and LamadridHorwitz et al., 1995). However, it was criticised for undermining the SNS because it relied on SNS capacity and infrastructure, which was not available to people who could not afford to pay extra.

The emergence of private health insurance

Following elections in 1970, incoming president Salvador Allende hoped to build a unified health service (Servicio Unico de Salud) that would bring together the public and private components of the system and integrate SERMENA into the public health system. Because this would have limited choice previously available to a privileged group of people, it faced opposition. In 1973, a military coup led by General Augusto Pinochet swept the Allende government out of office. The Junta’s social and economic policy was shaped by neoliberal ideas and the following years therefore saw a radically reduced involvement of the state in the delivery of services. In 1975, the Junta decentralized the SNS, so that it was organized as 27 regional health trusts. Responsibility for primary care was transferred to municipalities (Sistema Nacional de Servicios de Salud). The role of the Ministry of Health was largely limited to national goal-setting and policy-making. In contrast to the previous integrated system, the new approach separated funding, provision and regulation, and allowed the private sector to be involved in both funding and providing health care. Providers were paid on a fee-for-service basis and choice was opened up to anyone who could afford to purchase a voucher. In 1979, the SNS and SERMENA were merged through decree to form FONASA.

These reforms prepared the ground for the entry of private health insurance. A 1980 decree (Law Decree 3.626) created the legal and institutional framework, stipulating that all workers in the formal economy would pay a mandatory 4% of their taxable earnings or pension income into a central health fund, but would then be able to choose to join FONASA or a private insurer (ISAPRE) (in which case the contribution would be transferred to the private insurer). The reform also introduced the tiered system still in use today within FONASA. Category A and B users (unemployed people or informal sector workers) were exempt from making contributions and joined FONASA by default; they usually had no choice of provider and were exempt from user charges. Users in categories C and D, in contrast, enjoyed more choice but were also required to pay user charges (10% of the services tariff in category C, 20% in category D).

Individuals opting for private cover usually also had to pay user charges. Legislation required ISAPREs to cover services covered by FONASA (that is, the “basic plan” for category A and B). However, in contrast to FONASA, ISAPRE user charges were not regulated and could therefore be substantial. To begin with, about 50% of those who were privately insured had previously been covered by one of the more privileged Cajas (for workers employed in mining or railroads) that had not been part of the SNS (Reference Scarpaci and ScarpaciScarpaci, 1989). These mostly joined “closed” ISAPREs exclusively available for members of certain companies or unions. Contracts with private insurers were for 1 year and extensions were subject to review, allowing private insurers to increase premiums substantially over time. However, if a contract could not be renewed or an ISAPRE customer wanted to leave the scheme, he or she was allowed to join FONASA unconditionally.

Development of the private health insurance market in the 1980s

Uptake of private health insurance was initially slow in the 1980s, its share only growing from 0.5% of the population in 1981 to 4.5% in 1986 (Reference RaczynskiRaczynski, 1994). This was attributed to the high cost of premiums, the economic recession of 1981–1983 and reluctance among users to enter the market. There were also concerns about coverage limitations for maternity and sick pay, which by law had to be included in both FONASA and ISAPRE plans. Several private plans also refused to enrol married women without a separate income and/or required female applicants to undergo a pregnancy test (Reference Scarpaci and ScarpaciScarpaci, 1989). As a result of the economic crisis and devaluation of the national currency in the early 1980s, many private insurers faced increasing deficits (Reference Scarpaci and ScarpaciScarpaci, 1989). The situation improved after 1986 when legislation was introduced requiring private insurers to make provisions for maternity and sick pay, for which insurers were compensated through tax funding. Low-income earners who had taken out private insurance also became eligible for a tax break of 2% of their gross earnings (this was abolished in 2000). Mandatory contributions for both ISAPRE and FONASA rose from 4% in 1981 to 6% in 1983 and 7% in 1986, an increase of 88% in 6 years (Reference Scarpaci and ScarpaciScarpaci, 1989).

The number of privately insured people increased in the second half of the 1980s, rising from under 500 000 in 1985 to 1.4 million in 1988 (about 11% of the population), mainly in response to the improved economic climate, which increased salaries. The number of private insurers rose from 17 to 31 during the same period, with smaller companies entering the market (Reference Scarpaci and ScarpaciScarpaci, 1989). The market share of the three largest insurers fell from 74% in 1981 to 46% in 1988 (Reference Scarpaci and ScarpaciScarpaci, 1989). Migration of wealthier people from FONASA to ISAPRE meant a loss of income for FONASA. By 1988, the ISAPRE system covered 11% of the population but collected more than half of all mandatory contributions, accounting for 38% of total spending on health (Reference RaczynskiRaczynski, 1994). Reference RaczynskiRaczynski (1994) argues that resources previously collected by the state were increasingly directed to the private sector.

Major health insurance reforms of the 1990s

Following the return to democracy in 1990, health sector reform was a priority for the newly elected government. Between 1990 and 1994, the government tried to rebuild and modernize public health services, largely to compensate for previous structural adjustment programmes and budget cuts. Although health care was a concern throughout the 1990s, reforms to the health insurance system failed to generate the support required for large-scale changes, mainly due to strong opposition in Congress from right wing senators appointed by the army. Between 1994 and 2000, the government tried to circumvent this opposition by promoting the modernization of the public health sector and fostering competition between public and private schemes to improving the efficiency of both parts of the system.

Between 2003 and 2005, led by a centre-left government that had declared health reform a priority, parliament approved comprehensive legislation, including changes aimed at addressing the inequities arising from a dual health insurance system. The Financing Law (Law no. 19.888) introduced in 2003 increased taxes on alcohol and cigarettes and raised the VAT rate from 18% to 19% so that the additional 1% could be allocated to health care. It also increased the level of revenue transferred from the central government to the public health system (Minsal, 2008). Government transfers are still crucial, given the low incomes of the population (the average monthly salary in 2013 was approximately €564) and the low share of wage-related contributions in FONASA’s budget. In 2013, only 42.5% of FONASA members made such contributions and the share of these contributions has historically accounted for less than 60% of FONASA’s budget (Superintendencia Reference de Saludde Salud, 2015).

Further legislation (Law no. 19.895, called the “Short Law for ISAPREs” because of its relatively uncontroversial nature), enacted in 2003, introduced additional requirements to ensure financial solvency and transparency among private insurers. The Health Authority Act was introduced in 2004 to strengthen the supervisory role of the Ministry of Health vis-à-vis insurers. Importantly, legislation passed in 2003 defined a set of medical conditions, referred to as “explicit health guarantees” (Garantias Explicitas en Salud, AUGE), that private plans must cover for a premium that is community-rated across insurers. The selection of conditions covered rose from 25 in 2005 to 80 in 2016, reflecting the national burden of disease and disability. User charges for explicit guarantee services were regulated (for both ISAPRE and FONASA) and the privately insured had to access them through a network of preferred providers. FONASA members were allowed to seek care from a private provider if the public sector was not able to deliver the service within a certain period of time. The explicit guarantee system therefore acted as a waiting time guarantee.

The “Long Law for ISAPREs” was introduced in 2005. It applied community rating to ISAPRE premiums and established rules for premium setting. Both these rules and the community rating of premiums were strongly opposed by the association of private health insurers and right-wing politicians in Congress. The law set the rate of annual premium changes for ISAPRE (to be calculated based on a table of risk factors) and created a risk equalization scheme (Fondo Compensatorio Solidario) among open ISAPRE schemes to fund explicit guarantees. This was meant to standardize the price of services in both sectors for selected conditions. In addition, plans that covered services beyond those included in the explicit guarantee had to cover the same range of services covered by FONASA for users in category D and guarantee choice of provider. It was hoped that, by regulating premiums, coverage and prices through preferred-provider arrangements within the explicit guarantees system, would encourage providers to standardize services, discontinue the practice of treating patients differently based on their insurance status and improve quality of care, with these positive effects increasing as the AUGE system expanded.

Implementation of the “Long law” in 2005 met with heavy criticism from private insurers because the changes introduced substantially increased their financial risk. At the same time, patient groups regarded some of the indicators included as risk factors, such as sex and age, as discriminatory and challenged their constitutionality in court. The table of risk factors was declared unconstitutional by the Constitutional Tribunal in 2010 (though it is still in effect), a decision that effectively reversed the 2005 law and presented an important setback to the agreements reached in Congress.

Overview of the market for private health insurance in Chile

Market structure

In 2015, private health insurance was offered by 13 insurers, with the three largest holding a market share of almost 60% (Reference SánchezSánchez, 2014). Seven of these insurers were open ISAPRE schemes and the other six were closed ISAPRE schemes covering workers in the mining industry and railroads, and civil servants. There is also a growing market for complementary and supplementary health insurance, with 12.3% of the population having purchased some sort of complementary or supplementary insurance plan in 2010 (Reference SánchezSánchez, 2014).

Complementary or supplementary insurance is offered almost exclusively through group contracts (87% of the complementary market; Departamento de Estudios y Desarrollo 2008) and plans typically provide greater choice of provider, a reduction in user charges and increased cover for catastrophic illness, which is often capped by private plans for conditions not covered by the explicit guarantees, such as trauma.

Before the introduction of the explicit guarantees, about 40 000 different ISAPRE plans were on the market. It is estimated that their number has increased to 64 000, indicating that reforms have not produced the desired convergence of plans (Comisión Asesora Presidencial, 2014).

Eligibility

Health insurance is in principle compulsory for all workers, pensioners and unemployed people, although in practice the latter (as well as those employed in the informal sector) are not required to make contributions. Everyone except miners can choose to join FONASA or an ISAPRE scheme. Traditionally seen as being of strategic importance, miners working under permanent contracts are automatically privately insured, usually in one of the closed plans.

Premiums and policy conditions

Private health insurance in Chile is available to those able to afford the premiums. Financing has been historically based on mandatory wage contributions (7% of wage income up to a ceiling; see above). These contributions are capped at €186 per month, as are contributions made by FONASA members (Superintendencia Reference de Pensionesde Pensiones, 2015). However, if this mandatory contribution does not cover the full price of the private health insurance premium, households must pay the difference themselves. Companies offering private plans are also allowed to negotiate wage-based contributions with customers that exceed the statutory ceiling if they wish to offer additional services not covered by the basic premium or a larger choice of providers (Reference Bastías, Pantoja, Leisewitz and ZárateBastías et al., 2008). Although the cap may in theory increase the financial risk borne by ISAPRE schemes, the risk is in practice small due to cream-skimming practices applied when contracts are renewed (see below). FONASA contributions are very low in comparison. For someone in category C (the second highest income category), assumed to have a monthly income below €380, the monthly FONASA contribution would be about €27.

Private premiums are based on individual risk (age, sex) and characteristics (number of dependants covered), with a proportion of the price calculated as a community rate to cover the explicit guarantee conditions introduced in 2003. Contracts are usually annual and extensions are subject to a review based on individual risk factors. Insurers can reject applications and limit cover of nonguaranteed services. Before 2003, they were also allowed to cap benefits through “stop-loss” clauses for cover of catastrophic events or chronic conditions (Reference JackJack, 2002). Stop-loss clauses meant services could be excluded from cover at a time when the insured needed them most, creating a powerful disincentive for higher-risk people to opt for private cover and a strong incentive for the privately insured to switch to FONASA once they had reached the limit of their private plan. They therefore led to further segmentation of the national health insurance “market”. The introduction of explicit guarantees and catastrophic cover with a cap on deductiblesFootnote 10 put an end to this practice; insurers are no longer allowed to limit cover of guaranteed services.

Following earlier attempts to limit financial risk for the privately insured (see footnote 97), the Superintendencia de Salud (an arm’s-length regulatory body set up following the merger of the regulator for statutory cover and the ISAPREs regulator) has had greater oversight of premiums since 2003, although many of the original rules were contested by insurers. Insurers must now set premiums within 30% of a basic premium set by the insurer, which limits their ability to differentiate between plans and enrollees. The Superintendencia sets parameters for the risk factors used to calculate premiums, a more controversial change that was fiercely opposed by insurers and deemed unconstitutional in 2010. This policy was combined with the creation of a risk equalization mechanism, extensively elaborated in the Long Law and overseen by the Superintendencia. The mechanism, based on age and gender, virtually redistributes resources between insurers. It was also strongly opposed by insurers and, so far, its impact on risk selection has been negligible, especially given that AUGE (since renamed as Garantías Explícitas de Salud) benefits for ISAPRE users do not allow for a choice of provider (a preferred network of providers has to be used) which for many users was an important factor when choosing private health insurance.

Benefits

The privately insured have access to a wide range of private providers and the private sector is seen as providing more choice and faster access. FONASA members with complementary voluntary health insurance also have access to a wider range of providers (with the scope of entitlement dependent on the contract chosen). ISAPRE benefits are required by law to match FONASA entitlements. Any additional benefits are negotiated with enrollees based on guidelines set by the Superintendencia.

Contracts are typically annual. Enrollees can lose their private cover if they become unemployed, although they can then switch to FONASA. Conversely, they can remain privately insured on a voluntary basis. Since the introduction of explicit guarantees, insurers’ ability to increase premiums arbitrarily is much more limited. Cost-sharing requirements for the privately insured are substantial. In 2006, half of all private plans covered only 70% of the costs of ambulatory care and 90% of the costs of inpatient care (Reference PerticaraPerticara, 2008) and out-of-pocket payments (at 32.4% of total spending on health in 2016 compared with the OECD average of about 20% (2015 data); OECD, 2017) remain a serious barrier to accessing health care services (Reference 218Pedraza and ToledoPedraza & Toledo, 2012; Reference CidCid et al., 2006). Inequalities arising from the way in which ISAPRE benefits are priced and defined have been well documented. Reference PerticaraPerticara (2008) concluded that both FONASA and ISAPRE schemes imposed a high burden of cost sharing on patients, but that financial risk was substantially higher for the privately insured than the publicly covered. She also showed that user charges paid by the poorest 5% of the population were about 200 times higher, proportionately, than those paid by the wealthiest 5%. ISAPRE users continue to incur larger out-of-pocket payments than FONASA users not only in absolute terms, but also in terms of the share of their incomes – in 2013 out-of-pocket payments accounted to, respectively, 6.1% and 3.8% of the incomes of ISAPRE and FONASA members (Reference 218Pedraza and ToledoPedraza & Toledo, 2012; Reference Castillo-Laborde and Villalobos DintransCastillo-Laborde & Villalobos Dintrans, 2013).

Paying providers

ISAPREs pay providers on a fee-for-service basisFootnote 11 using market prices negotiated with individual providers and, in some cases, negotiating prices in bulk with preferred providers (see above). Most insurers offer a list of preferred providers with whom discounted prices have been negotiated. Fees are also agreed collectively in the case of services covered by the explicit guarantees. To control costs, many insurers have vertically merged with service providers (see above). Nevertheless, fee-for-service at prevailing market prices remains the predominant payment mechanism for most insurers, providing incentives for providers to give preferential treatment to the privately insured (and those opting for provider choice under FONASA) and to over-provide profitable services to them (Reference 220Vergara-Iturriaga and Martínez-GutiérrezVergara-Iturriaga & Martínez-Gutiérrez, 2008). So far, this approach to paying providers has not been challenged.

Legislation and regulation

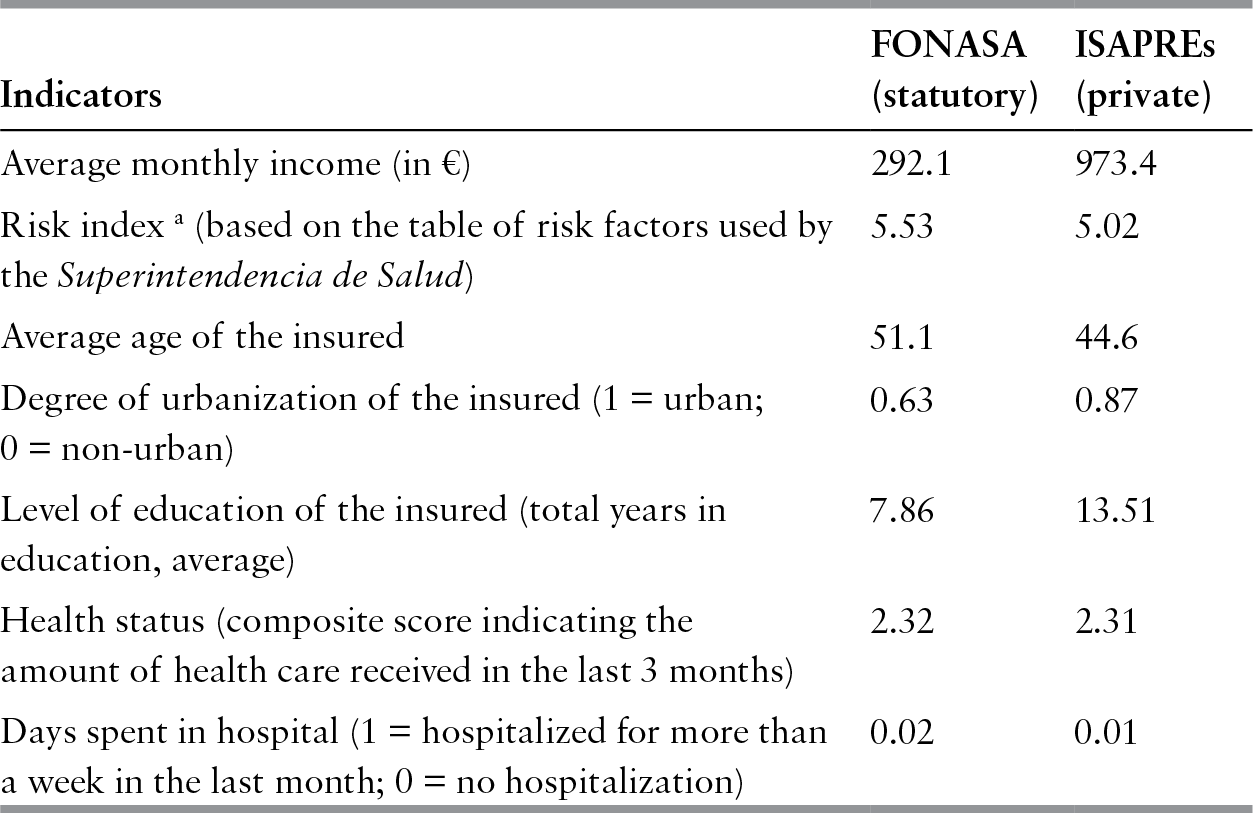

Since the reforms of the early 2000s, regulation of the private insurance industry has substantially increased (Table 6.1). Much has been done to increase transparency for consumers and limit the financial risk for enrollees associated with catastrophic events, risk selection, stop-loss clauses and user charges. The Superintendencia de Salud oversees market conduct and financial performance and also acts as an advocate for consumers. It regulates both statutory and private cover.

Serious concerns have been raised about potential collusion among private insurers, which would undermine competition (Reference Agostini, Saavedra and WillingtonAgostini, Saavedra & Willington, 2008). Reference Agostini, Saavedra and WillingtonAgostini, Saavedra & Willington (2008) suggested that the five largest insurers offered plans with identical user charges with coverage below the level prescribed by the Superintendencia (only reimbursing 90% instead of 100% of the cost of inpatient care and 70% instead of 80% of the costs of outpatient care). In 2005, the National Economic Prosecutor (Fiscalía Nacional Económica) brought the insurers to court. The insurers were acquitted in the first instance and later also by the Supreme Court of Justice, which established that parallel behaviour was insufficient to prove tacit collusion.

The impact of private health insurance in Germany and Chile

The following paragraphs attempt a comparative assessment of the operation and regulation of private health insurance in both countries and its effects on financial protection; equity in relation to financing and access to health care; and the problems arising from risk selection and market segmentation. The relationship between statutory and private health insurance is complex and in both countries both types of cover are heavily regulated. In its origin, the Chilean approach was inspired by Bismarck’s reforms, which laid the foundation for statutory health insurance and, in doing so, shaped private health insurance.

Table 6.1 Development and regulation of private health insurance in Germany and Chile, 1970–2016

| Germany | |

| 1970 | Expansion of mandatory statutory health insurance to white-collar workers; white-collar workers with earnings above a threshold continued to be allowed to opt for private health insurance |

| 1989 | Introduction of choice of statutory or private health insurance for all individuals with higher earnings |

| 1990 | German Reunification |

| 1994 | Introduction of the PKV standard tariff |

| 1994 | Introduction of the age limit for returning to the GKV: individuals aged 65+ cannot return to GKV (lowered to 55+ in 2000) |

| 2001 | Introduction of a compulsory ageing reserve surcharge of 10% on all PKV premiums |

| 2004 | Statutory health insurance funds allowed to sell voluntary complementary and supplementary policies |

| 2007 | Extension of qualifying period during which individuals have to be earning above the threshold in order to be allowed to opt out of the GKV (from 1 year to 3 years) |

| 2009 | Health insurance (statutory or private) made mandatory; PKV basic tariff made a legal requirement; introduction of portability of ageing reserves to reduce barriers to switching insurer among the privately insured |

| 2010 | Qualifying period extended in 2007 reduced to 1 year; extended to 2 years in 2011 |

| 2011 | Discounts for medicines negotiated by statutory health insurance funds are valid for PKV also; access to PKV for high-income employees is improved: individuals need to have income above the threshold for 1 year only |

| Chile | |

| 1973 | Military coup bringing the Military Junta to power |

| 1979 | Merger of SNS and SERMENA to form FONASA; decentralization of the health system and formation of 27 autonomous regional health trusts |

| 1980 | Establishment of private health insurance represented by ISAPRE; FONASA to become the regulator of private health insurance |

| 1986 | Introduction of the Ley de Salud (Health Act) |

| Chile | |

| 1989 | National referendum and beginning of transition to democracy |

| 1990 | Creation of the Superintendencia de ISAPREs as the regulator for private health insurance |

| 2000 | Introduction of mandatory catastrophic insurance coverage (CAEC); the aim of this policy was to cap payments at a threshold, to reduce the financial burden experienced in cases of serious illness |

| 2003 | Introduction of the system of “explicit health guarantees” (AUGE), standardizing insurance plans; private insurers must provide these explicit guarantees at a community-rated price and within a preferred-provider framework; user charges are regulated for both ISAPRE plans and FONASA |

| 2005 | Creation of the Superintendencia de Salud as a regulator for the entire health care sector and health insurance market; enactment of the “Long ISAPRE law”, which applied community rating to ISAPRE premiums and introduced strict rules for the setting of premiums in the future – annual premium changes for ISAPRE were to be calculated based on a table of risk factors; a risk equalization scheme (Fondo Compensatorio Solidario) was created as a mechanism to fund the community-rated explicit guarantees |

| 2010 | Constitutional Tribunal declares the table of risk factors unconstitutional, effectively reversing the 2005 law |

| 2010 | Establishment of the hospital concession programme (arrangements between public and private health care providers, whereby the private sector designs, builds, finances and maintains hospital infrastructure and the public sector reimburses the delivery of services provided in this setting); the programme ran until 2014 |

| 2011 | Abolition of the 7% mandatory health care contribution for pensioners over the age of 65 |

| 2014 | Report of the Presidential Commission for Health Reform (Comisión Asesora Presidencial Para El Estudio Y Propuesta De Un Nuevo Régimen Jurídico Para El Sistema De Salud Privado) sets out nonbinding recommendations for private health insurance reform, including the return to a single-payer public insurance system. A minority report proposed introducing a broader minimum health plan, at a single premium, into the private system, with a compensation fund for reducing risk-selection behaviour (which could also eventually be open to FONASA) (Reference Bossert and LeisewitzBossert & Leisewitz, 2016); so far none of these recommendations has been implemented |

| Chile | |

| 2015 | The Financing System for Diagnosis and Treatment of High Cost Programmes (Ley Ricarte Soto) established to increase financial protection and catastrophic coverage for illnesses not included in the explicit guarantee regimen for both ISAPRE and FONASA users |

Notes: FONASA: Fondo Nacional de Salud; GKV: gezetzliche Krankenversicherung; ISAPRE: Instituciones de Salud Previsional; PKV: privaten Krankenversicherung; SERMENA: Servicio Medico Nacional de Empleados; SNS: Servicio Nacional de Salud.

Both countries are unusual in offering people a choice of statutory or private health insurance but there is substantial variation in regulating the boundary between statutory and private cover. In Germany, the choice is largely limited to people with earnings above a legally defined threshold; those who choose substitutive private cover face substantial barriers to returning to the statutory scheme (the GKV) and in fact cannot return to it if they are over 55 years old. In Chile, anyone can opt for substitutive private cover and there are no restrictions on switching back to statutory cover; people can freely access publicly provided care should they lose their private cover.

Substitutive private health insurance covers about 11% of the population in Germany and 18.2% in Chile. Private cover is generally taken out by wealthier people, although there are some exceptions in Germany, where civil servants and those who have opted out and are over 55 are privately insured by default, irrespective of income. In Chile, private cover is attractive to those who can afford the premiums because it offers greater choice of provider, particularly access to private providers. FONASA members must pay extra to access privately provided services. Private cover also allows people to avoid the waiting lists that afflict the public sector. In contrast, the additional benefits offered by private cover in Germany are relatively modest, as both the publicly and privately insured draw on more or less the same pool of public and private providers. However, there is some evidence to suggest that those with private cover experience shorter waits in ambulatory care and in hospitals (Reference SchwierzSchwierz et al., 2011).

The two countries share similar concerns about the interaction between statutory and private health insurance in three areas. First, the payment mechanisms associated with private cover tend to distort priorities in care delivery by creating incentives for providers to treat private patients preferentially. This problem affects all types of health care in Chile, whereas in Germany it is most dominant in the ambulatory sector, where office-based doctors are allowed to charge higher prices for private than for statutory patients. However, incentives to over-provide services arising from fee-for-service payment are not restricted to private insurers in either country. Second, there is evidence of risk segmentation due to the selection of low risks by private insurers (see below). Third, there are substantial concerns about cross-subsidization between statutory and private cover, although the direction of these transfers is not entirely understood.

In both countries, the political costs of reforming (or abolishing) substitutive private health insurance are significant because private health insurance enjoys the support of health professionals and wealthy beneficiaries unwilling to forsake its advantages. Nevertheless, policy-makers have managed to address some concerns over time, although the pace of reform has differed. Chile has been able to achieve major reform in the last 15 years only, resulting in the introduction of a risk equalization mechanism (of limited effectiveness), and increasing catastrophic cover, among other things. In Germany, policy-makers have introduced successive reforms since the mid-1990s, but the main driver of risk selection – the option for wealthier people not to contribute to statutory cover – has not been removed.

Perhaps related to the above are differences in socioeconomic context. Public services in Chile still face substantial resource constraints, hence the need to ration care through waiting times. Some governments have promoted private health insurance as a panacea, a means of improving efficiency, reducing public sector bureaucracy and limiting pressure on public budgets. In Germany, high spending on health care (public and private), as well as high consumer expectations, have created a climate where rising costs are a constant concern. In the past, pressure to reform has mostly been felt in the statutory system. However, in recent years hikes in premiums, the rising number of defaulters and low interest rates in the capital markets have put substantial pressure on private insurers to control costs.

Financial protection

Health coverage is universal in both countries, but in Germany all residents are required to be covered and some who have opted for private cover are unable to return to the statutory scheme. In contrast, people in Chile do not have to pay contributions to FONASA and can still access publicly provided health services; additionally, those who opt for private cover can return to FONASA at any time. This difference has important implications. Arguably, ensuring financial protection for those with substitutive private cover ought to be a lower public policy priority in Chile than in Germany. However, in recent years both countries have introduced reforms to enhance financial protection among the privately insured.

Private insurers in Germany are allowed to set premiums reflecting individual risk and to exclude cover of pre-existing conditions, but they must cover both inpatient and outpatient care and match the benefits offered by the GKV. Deductibles are capped. Legislation also limits increases in premiums to what is necessary to maintain the financial viability of the insurer. During the 1990s, substitutive premiums rose sharply for many older people, in part due to previous miscalculation by insurers. To prevent this from happening again, the government requires insurers to impose a permanent surcharge on new subscribers to build up sufficient “ageing reserves”. Survey data from 2005 indicate that about 350 000 people (or 5% of those) with substitutive cover paid premiums that were higher than the maximum GKV contribution, and the average age of this group was 61 years (Reference Grabka, Jacobs, Klauber and LeinertGrabka, 2006).

In Chile, the government introduced “explicit guarantees” for the treatment of selected conditions in 2003, to ensure the provision of minimum benefits for those with private cover. However, the policy has still not been applied consistently, with persistent problems of access and financial protection for patients and increasing hospital debts due to the purchase of guaranteed services from private providers. Reforms have also introduced premium pricing controls (including a community rate for services included in the explicit guarantees), a risk equalization mechanism, the abolition of stop-loss clauses that capped benefits, and regulation of user charges. The table of risk factors used to limit risk rating was declared unconstitutional in 2010 and negotiations in Congress have not resolved this issue. Private premiums are significantly higher than contributions to FONASA, a problem compounded by high user charges.

Equity

Critics of Germany’s dual insurance system argue that substitutive private health insurance undermines equity in the health system as a whole. Higher earners, especially when they are young and healthy, benefit from being able to buy private cover for less than they would have to contribute to the GKV. Questions have also been asked about the effect of the substitutive market on the GKV, particularly as the GKV loses the contributions of those who leave it, an issue exacerbated by the fact that those opting out are largely higher-earning low risks. Some argue that the loss of income results in the GKV indirectly subsidizing the privately insured (particularly if it is mainly poorer high-risk individuals that eventually return to the GKV). Preventing older people from returning to the GKV has been one way of addressing this issue, as has increasing the qualifying period for opting out from 1 year to 3 years (although the latter policy was eventually reversed). Conversely, the association of private insurers (PKV) claims that the privately insured indirectly subsidize outpatient care for GKV members because outpatient doctors can (and do) charge higher fees to private patients (Reference Niehaus and WeberNiehaus & Weber, 2005). However, it is not clear whether these additional funds are used by providers to benefit GKV members. Office-based physicians tend to argue that outpatient (specialist) practices depend on the income from privately insured people, but arguably these higher fees contribute to cost inflation in the health sector (Reference Busse and RiesbergBusse & Riesberg, 2004).

Several studies confirm variation by insurance status in waiting times for appointments with outpatient specialists in Germany, with a 2008 study showing GKV members waiting about three times longer than privately insured people (Reference Mielck, Helmert and BöckenMielck & Helmert, 2006; Reference Schellhorn, Böcken, Braun and AmhofSchellhorn, 2007; Reference LüngenLüngen et al., 2008; Reference SchwierzSchwierz et al., 2011). The difference between the two groups ranged from 24.8 working days for a gastroscopy to 17.6 working days for an allergy test (including pulmonary function test) and 4.6 days for a hearing test (Reference LüngenLüngen et al., 2008). The studies show mixed results in terms of variation in satisfaction levels. Research also shows that the privately insured have faster access to patented and innovative drugs than GKV members (Reference KrobotKrobot et al., 2004; Reference ZiegenhagenZiegenhagen et al., 2004).

Variation in access to care by insurance status is modest in Germany compared with Chile. Criticisms about the impact of substitutive private cover on equitable access to care have been repeatedly voiced in Chile, where privately insured people typically have significantly faster access to (a wider range of) health services (Reference Zuckermann and de KadtZuckerman & de Kadt, 1997; Reference Holst, Laaser and HohmannHolst, Laaser & Hohmann, 2004). Access variations are frequently cited as a cause of major inequalities in health care use and health outcomes (Reference Zuckermann and de KadtZuckerman & de Kadt, 1997; Reference JackJack, 2002; Reference Holst, Laaser and HohmannHolst, Laaser & Hohmann, 2004). Household survey data from 2006 show that use of health care was 30% higher in the wealthiest than in the poorest income quintile (Reference Fischer, González and SerraFischer, González & Serra, 2006), while a 2003 study found that people with the lowest incomes had the worst self-rated health (Reference SubramanianSubramanian et al., 2003). These inequalities in health care utilization and self-rated health appear to have persisted at least up to 2013 (Ministerio de Desarrollo Social, 2013).

Risk segmentation

Substantial segmentation of the national risk pool attributed to allowing people to choose between statutory and private cover has been a major concern in both Germany and Chile. In Germany, the regulatory framework exacerbates risk segmentation, as (with the exception of the standard and basic tariff) private insurers are allowed to reject applications for cover, risk rate premiums, exclude cover of pre-existing conditions, charge extra for dependants and offer discounted premiums in exchange for high deductibles. The ability of private insurers in Chile to select “good” risks has been substantially curtailed by recent reforms, including the introduction of risk equalization, explicit guarantees and premium regulation. However, evidence of the effects of these changes is lacking and some of the measures have not yet been implemented consistently.

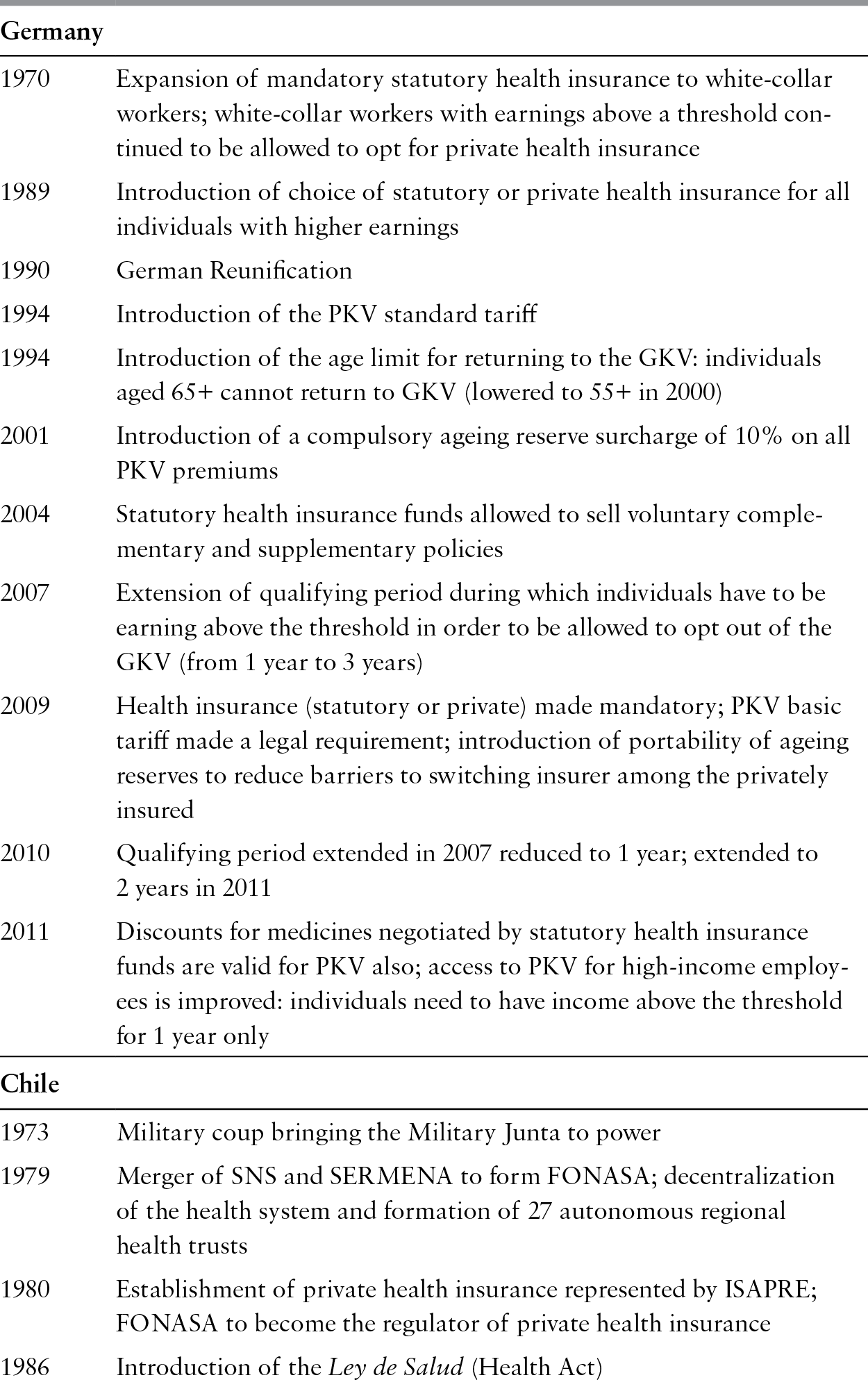

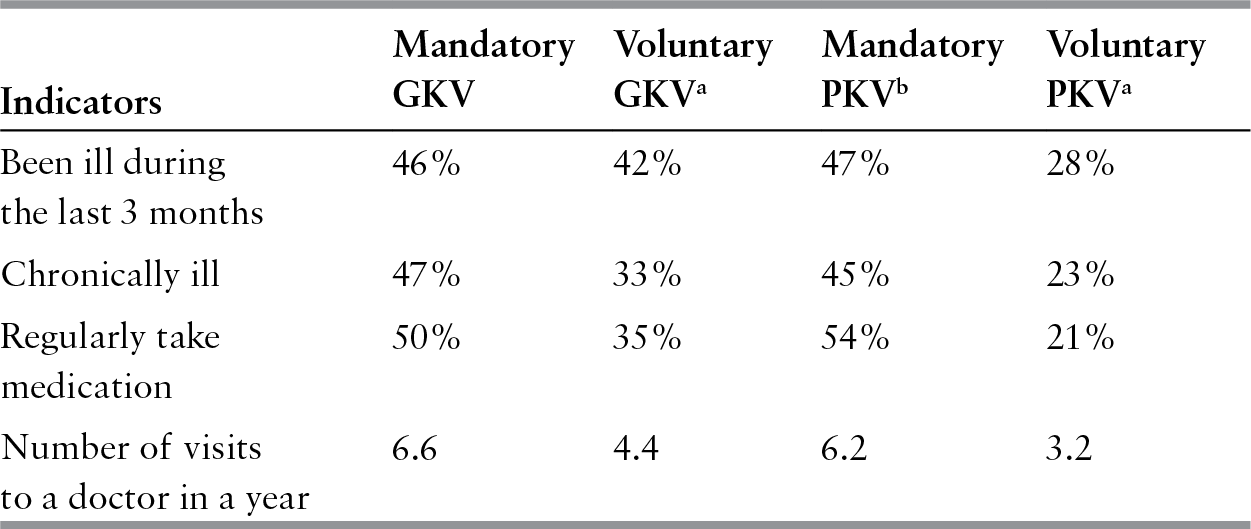

The substitutive market in both countries enjoys a high concentration of low risks, while the statutory scheme covers a disproportionate number of high risks, notably women and children, older people and individuals with larger families (see Tables 6.2 and 6.3). In Germany, in 2014, about 50% of the privately insured were men, while women and children accounted for 31% and 18%, respectively (PKV, 2015). Risk selection is highest among those with earnings above the threshold. Differences in health status and health care use are less visible among those who are required to be covered by the GKV and those who are privately insured by default (Reference Leinert, Jacobs, Klauber and LeinertLeinert, 2006). A similar pattern is seen in Chile, where older and poorer people are less likely to be privately insured than younger and wealthier people. Indeed as of 2013, the oldest and poorest quintiles of the population accounted for less than 5% of those covered by ISAPRE schemes (Reference Barrientos and Lloyd-SherlockBarrientos & Lloyd-Sherlock, 2000; Ministerio de Desarrollo Social, 2013). Using household survey data from 2000 and 2006, Reference Dawes IbáñezDawes Ibáñez (2010) showed that the probability of taking out private cover increases with income and decreases with risk of ill health.

Table 6.2 Health status and health care use among the publicly and privately insured in Germany, 2006

| Indicators | Mandatory GKV | Voluntary GKVa | Mandatory PKVb | Voluntary PKVa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 46% | 42% | 47% | 28% |

| Chronically ill | 47% | 33% | 45% | 23% |

| Regularly take medication | 50% | 35% | 54% | 21% |

| 6.6 | 4.4 | 6.2 | 3.2 |

Notes: GKV: gezetzliche Krankenversicherung; PKV: privaten Krankenversicherung.

a Includes those with earnings above the threshold and self-employed people.

b Includes civil servants entitled to Beihilfe and non-active people (for example, pensioners).

Table 6.3 Characteristics, health status and health care use among the publicly and privately insured in Chile, 2006

| Indicators | FONASA (statutory) | ISAPREs (private) |

|---|---|---|

| Average monthly income (in €) | 292.1 | 973.4 |

| Risk index a (based on the table of risk factors used by the Superintendencia de Salud) | 5.53 | 5.02 |

| Average age of the insured | 51.1 | 44.6 |

| 0.63 | 0.87 |

| Level of education of the insured (total years in education, average) | 7.86 | 13.51 |

| 2.32 | 2.31 |

| Days spent in hospital (1 = hospitalized for more than a week in the last month; 0 = no hospitalization) | 0.02 | 0.01 |

Notes: FONASA: Fondo Nacional de Salud; ISAPRE: Instituciones de Salud Previsional.

Differences in averages for all variables are statistically significant (P< 0.01).

a Although the risk index seems similar across both groups, there are important differences in its components, such as education and income levels.

Incentives for quality and efficiency in care delivery

One of the assumptions underlying choice of insurer is that competition will create incentives for quality and efficiency in care delivery. In Germany, however, the high costs involved in changing from one private insurer to another – now mainly due to risk-rated premiums and exclusion of pre-existing conditions but previously due to the non-portability of ageing reserves – has meant that there has been almost no competition among insurers for those already part of the substitutive market. Instead, competitive efforts have focused on attracting new entrants. From 2009, ageing reserves have had to be portable, which the government hoped would improve competition between private insurers. Competition between statutory and private health insurance does not seem to be a dominant policy objective in Chile, at least in the current political climate. But previous governments, particularly the military regimen of General Pinochet in the 1970s and 1980s, promoted the market by channelling subsidies to private insurers. This was, in part, a response to (perceived) burgeoning bureaucracy in the private provider system.

German private insurers face a major problem in being unable to control provider fees, although this has become increasingly debated. The GKV partly shares this problem, which can be attributed to a general lack of transparency in pricing and reimbursement. An internal paper prepared by the Federal Association of Sickness Funds showed that two in five invoices for hospital care were flawed or inappropriate, adding about €1.5 billion to the costs of hospital care (Spiegel online, 2010). Private insurers are particularly weak in challenging the billing practices of office-based physicians because they have little insight into the appropriateness of the services delivered. They may also be reluctant to challenge physicians due to the fact that they market themselves as being able to give enrollees better access to health care.

Private insurers in Chile face similar difficulties in controlling provider behaviour, partly due to fee-for-service payment, which provides strong incentives to over-provide services to (and over-charge) privately insured people. For example, caesarean section rates have been consistently higher among privately insured women than among those who give birth in public hospitals (Reference MurrayMurray, 2000; Reference GuzmánGuzmán, 2012; Reference Guzmán, Ludmir and DeFrancescoGuzmán, Ludmir & DeFrancesco, 2015). Market fragmentation may also contribute to private insurers’ weakness in negotiating with providers. Even so, private insurers in Chile seem to be more aggressive in purchasing than in Germany because, among other things, there is a more vertical integration of insurers and providers. Spending on administration per enrollee is about twice as high for private insurers as for FONASA (Reference CidCid et al., 2006; Comisión Asesora Presidencial, 2014).

What is the future for private health insurance?