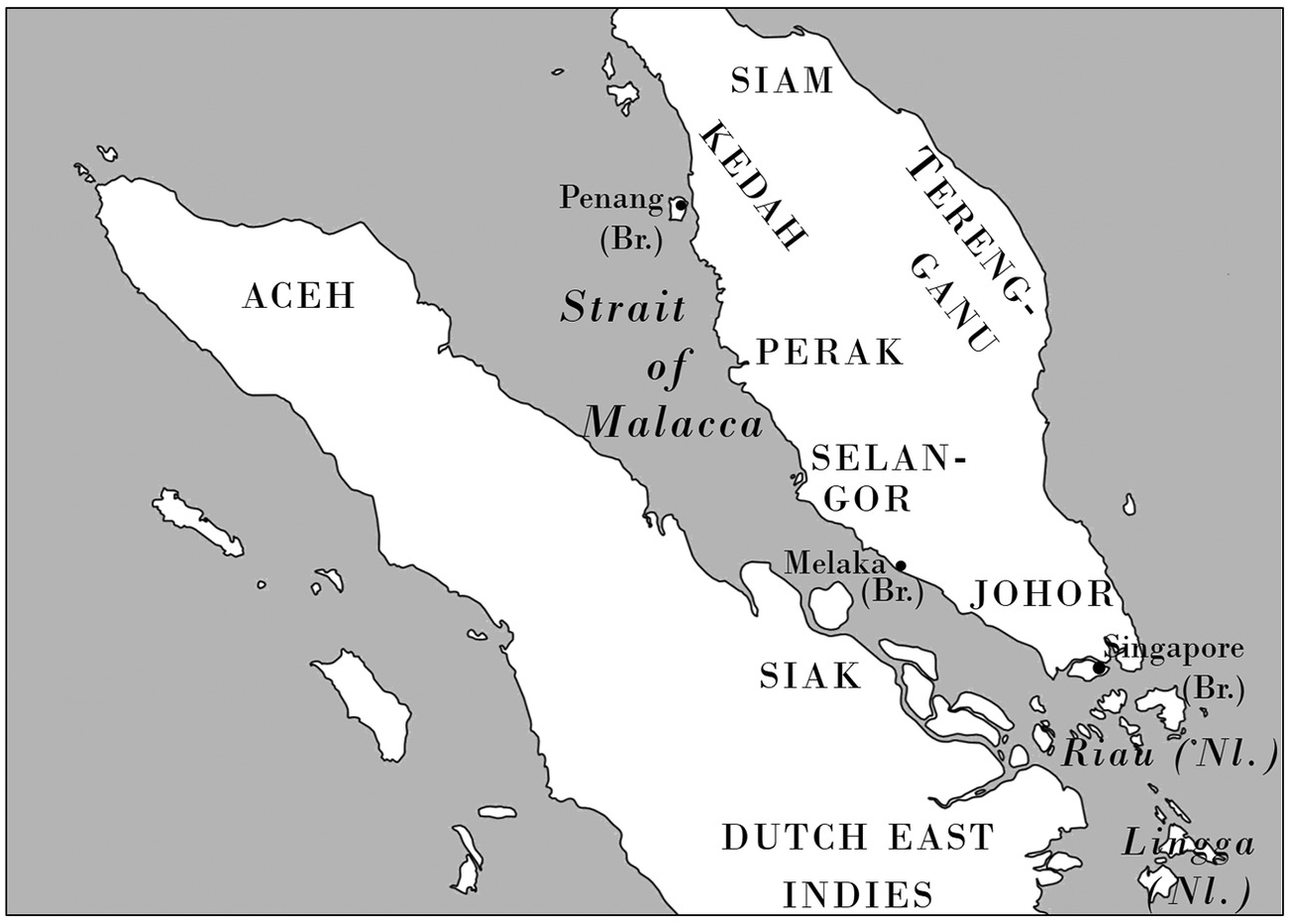

Next to the Sulu Sea the most pirate-infested region in Southeast Asia according to nineteenth-century colonial observers was the Strait of Malacca. The conditions for piratical activity were (and still are) in many ways formidable. The natural geography of the area, with many small islands, secluded bays, rivers and densely forested coastlines, was ideal for launching swift attacks and for evading capture afterwards. The southern part of the Strait of Malacca and the adjacent Strait of Singapore has throughout history been a bottleneck for regional and long-distance maritime commerce, which has provided raiders with a wealth of richly laden targets.

Given these circumstances it is unsurprising to find attestations of piratical activity in the Strait of Malacca since the earliest historical times.Footnote 1 Like elsewhere in the Malay Archipelago, piracy and maritime raiding in precolonial times were often linked to political processes, and the control of maritime violence and commerce was a key to political power as well as wealth. Piracy and maritime raiding thus fluctuated over time with political developments, and tended to increase in times of political instability and upheaval and, conversely, to decrease in times of political stability and centralisation.

The arrival of European navigators in the area from the turn of the sixteenth century triggered a period of political insecurity, characterised by an increase in piracy and maritime raiding perpetrated by both European and Malay navigators. In 1511 the Portuguese conquered Melaka (Malacca) on the west coast of the Malay Peninsula, the main commercial hub in Southeast Asia, which led to a dispersal of the trade previously centred on the port-city and a decline in its prosperity. The conquest also led to an increase in piratical activity in the Strait due to the demise of Melaka’s sea power, which previously had checked the activities of local raiders, and due to the Portuguese raids on Arab, Indian, Malay and other Asian shipping, and on coastal settlements.

Map 3: The Strait of Malacca

As in the Indian Ocean, the Portuguese tried to establish the cartaz system in the Strait of Malacca (and other parts of maritime Southeast Asia), but they had too few ships at their disposal in order to enforce it efficiently. Meanwhile, the decline of Melaka paved the way for the rise of Aceh in northern Sumatra and for Johor in the Riau Archipelago, both of which competed fiercely for the remainder of the sixteenth century with the Portuguese and with each other for dominance in the Strait. As in the southern Philippines, maritime violence and raiding were the dominating form of warfare in the struggle for power in the Strait of Malacca throughout the early modern era.

Dutch Expansion and Notions of Piracy

From the turn of the seventeenth century the Portuguese were gradually pushed out of Southeast Asia by the Dutch and, to a lesser degree, the English. The Dutch East India Company established itself as the dominant power in the Strait of Malacca and much of the rest of the Malay Archipelago (except for the Philippines), particularly after they established a permanent base in Batavia (Jakarta) on the north coast of Java in 1619 and conquered Melaka from the Portuguese in 1641. The company’s ruthless policy of conquering strategic ports and strongholds in the Indonesian Archipelago, killing or enslaving tens of thousands of people in the process, accelerated the decline of indigenous traders and rulers, and resulted in a sustained long-term drop in Southeast Asian commerce and prosperity.Footnote 2

For most of the early modern period Malay piracy was not a major problem for the Dutch East India Company or other European navigators in Southeast Asia. The European vessels were generally larger and better armed than those of their Asian competitors, and they were thus less likely to be attacked. The prevalence of piracy and maritime raiding in the Strait of Malacca and other parts of the Malay Archipelago in fact often benefitted European navigators, both because it struck at their commercial competitors and because of the opportunities that such activities offered for trade with the raiders or their associates. The Dutch and other Europeans thus readily sold arms and munitions to Malay pirates in exchange for slaves, contraband and pirated goods.Footnote 3

The fact that the Dutch thus indirectly thrived on piracy did not prevent them from using the word to discredit their enemies in the Malay Archipelago. For example, after the Dutch sack of Makassar in Sulawesi in 1669 large numbers of Makassarese and Bugis migrated and formed large fleets led by Bugis and Makassarese noblemen. They earned a reputation as formidable fighters and traders, and their services were welcomed by many indigenous rulers in the eastern parts of the Malay Archipelago.Footnote 4 They also engaged in maritime raiding, although piracy for private gain seems to have been relatively rare.Footnote 5 Dutch sources from the last decade of the seventeenth century nevertheless described the Makassarese raiders as full-fledged pirates, and decisive measures were taken in order to suppress them, even after most of the Makassarese diaspora had been repatriated to Sulawesi in 1680.Footnote 6

Just as in England, the decades around the turn of the eighteenth century marked a shift in the Dutch attitude toward piracy and maritime raiding. In the Dutch case, moreover, the new policy was conditioned by the adverse effects that the slave raids had on Dutch settlements and interests in Southeast Asia. The raids mostly emanated from the southern Philippines and the eastern parts of the Indonesian Archipelago that were outside the control of the Dutch East India Company. From the beginning of the eighteenth century the Company began to take measures designed to suppress piratical activity, both in the eastern parts of the Indonesian Archipelago and in the west, in and around the Strait of Malacca. In 1705 the company issued a detailed regulation that limited the number of crew members and passengers that indigenous craft were allowed to carry, obviously without concern for the increased vulnerability that the restrictions entailed for indigenous traders. From the middle of the century three cruisers were engaged to keep the north coast of Java free from pirates, and during the rest of the century further measures were taken to ensure that the indigenous rulers with whom the Dutch had friendly relations would cooperate in order to suppress piracy in and emanating from their lands.Footnote 7

Such measures notwithstanding, however, piracy and maritime raiding increased significantly, particularly after 1770, when raiding emanating from the Sulu Archipelago took off – stimulated, as we have seen, by the integration of the region into the commercial networks that connected Europe and East Asia and by the demand for slaves in the Dutch East Indies and other colonies.Footnote 8 The annual raids of the feared Iranun, or lanun (pirates), affected large parts of maritime Southeast Asia. Toward the end of eighteenth century the Iranun had also established forward bases in several places in the Strait of Malacca, including in Riau and along the east coast of Sumatra, and began to plunder the coasts and maritime traffic of the Strait systematically. The Iranun were drawn to the area by the opportunities for raiding offered by the burgeoning maritime traffic and by the power vacuum due to the decline of the Dutch East India Company and the political instability of the major indigenous power in the southern part of the Strait of Malacca, the Sultanate of Johor.Footnote 9

The complex historical, social and political reasons behind the surge in maritime raiding in Southeast Asia from the end of the eighteenth century were not entirely understood by contemporary Dutch colonial administrators and observers. As among other Europeans, the explanations generally focused on racial, cultural and religious factors. With regard to the latter, Islam was believed to be instrumental in sanctioning piracy and slave-raiding among the Malays. Pieter Johannes Veth, who was one of the leading scholars on the geography, history and culture of the Dutch East Indies in the nineteenth century, argued, for example, that piracy in the archipelago to a large extent should be understood as a form of jihad.Footnote 10 The religious antagonism, however, was less pronounced in the context of the Dutch East Indies than in the Spanish Philippines, and the Dutch did not try to make the Malays abandon their piratical habits by converting them to Christianity.

There was some disagreement among Dutch colonial officials as to whether certain groups of Malays should be labelled piratical or not, and as to which policies were most efficient for bringing an end to maritime raiding. The report by a Malay translator for the Dutch colonial government, Johan Christiaan van Angelbeek, from 1825, for example, presented an image of piracy in the Riau-Lingga Archipelago as a traditional way of life on the part the so-called Rayat Laut (lit. ‘sea people’), embedded in regional patterns of dependency and servitude to Malay princes and headmen. Rather than suggesting a military solution to suppress piracy – which was the method of choice for most Dutch colonial administrators and military officers at the time − Van Angelbeek proposed that antipiracy measures focus on offering alternative sources of income to the pirates in order to wean them from their traditional way of life.Footnote 11

For the most part Dutch efforts to deal with piracy in the first half of the nineteenth century focused on repressive measures. After the British handed back Java to the Netherlands at the end of the Napoleonic Wars the colonial authorities stepped up their efforts to enlist the support of indigenous sovereigns in an attempt to suppress piracy. The Malay rulers of several autonomous states in the archipelago, such as Lingga, Banjarmasin and Pontianak, signed, or confirmed, treaties of friendship with the Dutch government in which they, among other things, promised to punish pirates and not allow them to reside in their territory.Footnote 12 The Dutch, however, were aware that most indigenous rulers – to the extent that they were willing to cooperate in the suppression of piracy – had very limited means at their disposal, and the Dutch colonial government tended instead to rely above all on its own marine forces to suppress piracy and to prevent smuggling. Anglo–Dutch rivalry in the Strait of Malacca, moreover, provided a further rationale for strengthening Dutch naval power in the region, as did the Java War (1825–30), which brought about an increase in maritime raiding. As a consequence of these developments, Dutch forces in the Strait of Malacca, and in Southeast Asia in general, were much larger than the British. Dutch sea power was further strengthened in the 1830s, when a permanent coastguard was set up to suppress piracy and smuggling. In addition, several units of the Dutch Navy regularly cruised the colony’s archipelagic waters throughout the nineteenth century.Footnote 13

It seems that these efforts began to bear fruit from the 1840s, although it is not always immediately obvious which colonial power was responsible for the decline in piratical activity. In 1848, for example, there was a sharp falling-off in maritime raiding in the eastern parts of the Dutch East Indies. Dutch officials put this development down to the fear that the Dutch steamers aroused among those inhabitants of the colony who harboured piratical inclinations. It seems likely, however, that the Spanish destruction of the Sama base at Balangingi in the beginning of the year was at least as consequential in bringing about the decline in maritime raiding − possibly combined with the withdrawal of support and sponsorship by the Sulu Sultanate for the Iranun and Sama raiders.Footnote 14

As in the Spanish colony, there was little questioning among the Dutch of the use of the label piracy to describe the various bands of Malays who were responsible for the maritime violence in the archipelago, particularly in the press and among the general public in the Netherlands. The Dutch discourse about piracy in the East Indies tended to label all forms of maritime violence perpetrated by Malays as piracy and thus illicit, whereas coercive and violent practices on the part of the colonial government and European and other foreign individuals were seen as legitimate and regarded as a buffer against indigenous piracy.Footnote 15 The Dutch media was above all concerned with the extent and efficiency of the antipiracy measures taken and less with questioning the rationale and motives for designating various ethnic groups as piratical.Footnote 16

To the extent that criticism against the promiscuous use of the allegation of piracy and the excessive violence deployed to suppress it was voiced in the Dutch context, it came largely from government officials in the Dutch East Indies. In 1838, for example, the governor-general of the colony, J. C. Baud, complained to the Dutch government about a naval operation in Flores that had resulted in the destruction of fifty vessels and seven prosperous villages, and left 14,000 people homeless. A few years earlier the Resident of Riau had voiced similar apprehensions about the use of indiscriminate violence against alleged pirate communities.Footnote 17 Such voices were nonetheless rare and seem to have met with little sympathy in the Netherlands.

Piracy and British Expansion in Southeast Asia

Piracy, as we have seen, had been a topic of great public interest in Great Britain at least since the beginning of the eighteenth century. As the British expanded into Southeast Asia, particularly during the following century, piracy frequently became the object of considerable controversy in Great Britain, more so than in any of the other major four colonial powers in Southeast Asia in the nineteenth century. The great British interest in piracy can be explained by the importance of piracy in the country’s history, particularly in British overseas expansion – both with regard to the piratical imperialism of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and to Britain’s leading role in the struggle to suppress piracy from the turn of the eighteenth century. The cultural fascination with pirates as fictional or semifictional characters also served to stimulate public interest in piracy in its various guises.

Many nineteenth-century Britons associated piracy with the trafficking of slaves. The background to this association can be traced to 1807, when Parliament prohibited the slave trade and the Royal Navy was charged with the task of intercepting ships of any nationality suspected of trafficking slaves across the Atlantic. The Navy declared slave-trading to be on a par with piracy, a feat that served as a legal justification for the self-proclaimed right of Britain to intercept and search foreign vessels on the high seas.Footnote 18

Apart from the effort to suppress the transatlantic slave trade, British antipiracy operations in the first half of the nineteenth century were concentrated on the three areas where the problem seemed to be most serious: the Mediterranean, the Persian Gulf and the Malay Archipelago. In all three areas the vast majority of the alleged pirates were Muslims, and in line with the arguments made by contemporary Dutch and Spanish observers, Islam was seen as a corrupting force that encouraged both piracy and the abduction and trafficking of slaves. Piracy also began to be linked to the lack of civilisation on the part of certain nations or races, particularly Arabs and Malays.Footnote 19

John Crawfurd, a Scottish colonial official and scholar, who served in several capacities in the British colonial administration in Southeast Asia in the first half of the nineteenth century, was a leading proponent of stadial theory, and influenced subsequent British perceptions and policies pertaining to piracy in Southeast Asia. According to Crawfurd, there were hardly any maritime peoples in the Malay Archipelago that had not at one time or another engaged in piracy, and the only ones who were not inclined to piracy, at least not in present times, were the agricultural peoples of Java, Bali, Lombok, Sumatra and the Philippines under Spanish control.Footnote 20

British commercial interests in Southeast Asia can be traced to the beginning of the seventeenth century, but their presence in the region was for a long time limited to the west coast of Sumatra, where the English East India Company established a trading station at Benkulu (Bencoolen) in 1685. During the following century, British interests in Southeast Asia, particularly the Malay Peninsula, increased because of its strategic location between India and China, and its commodities, particularly tea and opium. In 1786 the company established a free port called George Town on the island of Penang off the west coast of the Malay Peninsula. A major purpose of Penang was to compete with the declining Dutch East India Company for the trade in the area, and Penang developed rapidly during its first decades, attracting large numbers of Chinese, Indian, Malay and European traders.Footnote 21

The founding of Penang coincided with a surge in maritime raiding in Southeast Asia after 1770 and the establishment of forward bases of the Iranun in Riau and the east coast of Sumatra in the 1780s. This maritime raiding, combined with the political instability of the Sultanate of Johor, led to a deterioration in maritime security, which threatened the commerce and prosperity of Penang. To a large extent these concerns explain the increase in British allusions to piracy in the Strait of Malacca from the end of the eighteenth century, but there were also pragmatic reasons for labelling the Malay raiders pirates. In 1784, the British Parliament had passed the East India Company Act, which aimed to bring the company’s rule over India more firmly under London’s control. The Act, among other things, cancelled the delegating of the presidencies subordinate to the governor-general in Calcutta to make war or negotiate treaties with foreign potentates without explicit permission from higher authorities, ultimately from London, except in the direst emergencies. The provision thus limited the scope for local initiative, and company officials in Southeast Asia began to look for a way to circumvent the restrictions. By extending the term piracy to include not only raids against ships for private gain but also naval operations and other forms of maritime violence sanctioned by indigenous sovereigns, British officials in Southeast Asia gave themselves carte blanche to take military action without seeking prior permission from London or Calcutta. British officials in the region also believed that the Malay nobility and others engaging in piratical activity had to be convinced that the British would not confine themselves to defensive measures but would be proactive in their efforts to uphold maritime security in the Strait of Malacca and other major sea-lanes of communication in the region.Footnote 22

The blueprint for much of British policy in Southeast Asia during the nineteenth century was drawn up by Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles, who served as lieutenant-governor of Java during the British occupation of the island between 1811 and 1815, and who in 1819 founded Singapore. Although Raffles gave different explanations for the prevalence of piracy in the Malay Archipelago in his many speeches and writings, he principally believed that piracy was a consequence of the commercial and political decline of indigenous commerce and polities due to the long-standing, ruthless and monopolistic commercial policies of the Dutch in the archipelago. Such policies, according to Raffles, were ‘contrary to all principles of natural justice, and unworthy of any enlightened and civilised nation’.Footnote 23

Like other British observers in the nineteenth century, Raffles did not necessarily see a contradiction between the historical and the racial or cultural explanations, or, in the words of Anne Lindsey Reber, the ‘decay’ and the ‘innate’ theories of piracy.Footnote 24 On the contrary: both explanations were consistent with stadial theory, and both also sat easily with the Orientalist trope of the decline and decay of formerly great Oriental civilisations. The attractive implication of this line of argument was that the British had a special obligation to bring civilisation and progress to the Malays and thus to end the decay imposed on them by two centuries of Dutch oppression. The best way to do so, according to Raffles, was to suppress piracy and slave-raiding by providing commercial opportunities:

We may look forward to an early abolition of piracy and illicit traffic, when the seas shall be open to the free current of commerce, and when the British flag shall wave over them in protection of its freedom, and in promotion of its spirit. Restriction and oppression have too often converted their shores to scenes of rapine and violence, but an opposite policy and more enlightened principles will, ere long, subdue and remove the evil.Footnote 25

Raffles further argued that the British should support the indigenous Malay rulers and strengthen their authority over their shores and over the lesser chiefs, who frequently were the instigators of piratical activities.Footnote 26

Such policies were implemented in Raffles’s lifetime and afterwards by means of so-called agreements or treaties of peace and friendship. Hundreds of such bilateral treaties were concluded in the course of the nineteenth century between Great Britain or the East India Company and Asian sovereigns of greater or lesser importance. The agreements typically regulated matters of sovereignty, jurisdiction and commerce, always to the advantage of the British, who invariably were the economically, politically and militarily stronger party. From around 1820 most of the treaties – like the corresponding Dutch and Spanish treaties with indigenous rulers in the archipelago − included one or several paragraphs in which both parties promised to do their best to suppress piracy in and around their territories. There was no explanation or legal definition of the words piracy or pirate in the treaties, however, a circumstance that served to give the British colonial officials and naval officers on the spot great leeway in deciding what constituted piracy, and to deploy harsh and often arbitrary measures to suppress it.Footnote 27

Anglo–Dutch Rivalry and the Suppression of Piracy

As in the Sulu Sea, the efforts of the colonial powers to suppress piracy and other forms of maritime violence in the Strait of Malacca in the nineteenth century were hampered by imperial rivalry. British expansion in the area was viewed unfavourably by the Dutch, who not only resented the commercial competition but also feared that that British might try to extend their territory and political influence to Sumatra, which the Dutch considered to be within their sphere of influence. The establishment of Singapore, which soon eclipsed Penang as the major British commercial and administrative hub in Southeast Asia, exacerbated these tensions, which in turn led to negotiations that eventually, in 1824, resulted in the Treaty of London between the two countries. The British ceded Benkulu to the Dutch in exchange for Melaka, and promised to respect Dutch sovereignty over Riau and other islands to the south of Singapore, whereas the Dutch withdrew their opposition to the establishment of Singapore. Both countries also agreed to take forceful measures to suppress piracy, but there was no concrete provision for naval cooperation or intelligence-sharing in the treaty.Footnote 28

In 1826 the British merged their three colonies in the Malay Peninsula, Penang, Singapore and Melaka, to form the Straits Settlements, and six years later the administrative centre was moved from Penang to Singapore, which had undergone rapid economic and demographic growth since it was founded. The new colony was still a part of the East India Company’s Indian possessions and subordinate to the governor-general in Calcutta. For almost fifty years, until 1874, official British policy was not to seek further territorial expansion in the Malay Peninsula or in other places around the Strait of Malacca. The emphasis was instead on maintaining friendly relations with the indigenous Malay Sultanates that controlled the rest of the peninsula, and on developing profitable commercial relations with merchants and producers regardless of origins or nationality. In contrast to the more aggressive policies pursued by the British in Burma, the policy in the Strait of Malacca before the 1870s was thus very much that of ‘Imperialism of Free Trade’, in the words of John Gallagher and Ronald Robinson. It was a policy that in many ways was advantageous to the British, as it relieved them of the burden of administering vast territories populated by potentially unruly or hostile populations while at the same time bringing great commercial benefits to the British, such as access to markets and commodities.Footnote 29

It was not only the British who profited from the country’s free trade policy. The Straits Settlements also attracted large numbers of merchants and workers, including Chinese, mainly from Fujian and Liaoning (Kwangtung), Malays, Indians, Arabs and other Europeans. The population of Singapore multiplied in the decades following its foundation, and by the 1830s it had become the main commercial entrepôt in Southeast Asia.Footnote 30

The Straits Settlements were vulnerable to piratical depredations, however, because they were an essentially maritime colony, the unity of which depended on the free flow of navigation in and out of the three settlements and between them.Footnote 31 Piracy and maritime raiding were a threat to the commerce of the colony and affected mainly the indigenous traders, whose small and weakly protected vessels were often easy targets for pirates. The problem was not alleviated by the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824, despite the two countries’ promise to act forcefully against pirates. Moreover, although Britain’s Royal Navy was the most powerful in the world, her sea power in Asian waters was limited and generally insufficient for the purpose of suppressing piracy and slave-trafficking.Footnote 32 As a result, piracy continued unabated throughout the 1820s and most of the 1830s, leading the Straits government to worry that native trade in the region would eventually become extinct.Footnote 33

The opportunities offered by the boom in maritime commerce combined with the lack of political control – on the part of both the colonial powers and the indigenous Malay states – made the Strait of Malacca a haven for maritime raiding. Marauders from around the archipelago were drawn to the area, including Malays from Johor, Riau-Lingga and Brunei, Bugis from Sulawesi, Dayaks from Borneo, Iranuns and Samas from the southern Philippines, and Acehnese from North Sumatra. In addition, Chinese pirates began to arrive in the region, particularly from the 1840s, as piracy surged in the aftermath of the Opium War. European and American adventurers also at times seized the opportunity and engaged in piratical raids.

Some of the pirates operated out of the Malay Peninsula, but most of them (apart from the Chinese) were based in Sumatra or the Riau-Lingga Archipelago, which was, at least nominally, under Dutch control. There were both small bands of freebooters and those who operated under the covert sponsorship of local Malay rulers, sometimes sponsored or led by members of a royal family or other notables. The predations of the major bands of pirates sometimes took the form of large-scale expeditions that could involve dozens of vessels and hundreds of men who attacked vessels at sea and in port and made coastal raids, mainly for the purpose of capturing slaves.

As among the Dutch, British knowledge about the identity and origins of the perpetrators was often scarce and confused, particularly before the 1830s. Moreover, despite the Treaty of 1824, mutual animosity and suspicion persisted between the Dutch and the British. These circumstances, combined with the lack of sea power on the part of the British, the region’s natural geography, the navigational skills of the pirates, and the speed and shallow draft of their vessels, rendered the task of suppressing piracy and other forms of maritime violence difficult for the colonial authorities.Footnote 34

Colonial officials tended to regard all Malays as more or less addicted to piracy, at least those who did not practise agriculture. Fishermen and others who lived on the coasts or around the estuaries of rivers were believed to be particularly prone to engage in piracy. According to Crawfurd, who was the resident of Singapore from 1823 to 1826, the maritime Malays were ‘barbarous and poor, therefore rapacious, faithless, and sanguinary’. Piracy, Crawfurd thought, was part of their character.Footnote 35

Despite such pervasive claims, which tended to regard Malays as pirates by nature, there were colonial and naval officials who expressed doubts about the sweeping use of the label piracy in the Malay context. In 1832 the commander-in-chief of British naval forces in the East Indies, Rear-Admiral Edward Owen, rejected the use of the term pirates to describe the Malay forces involved in a dynastic struggle in Kedah. To the dismay of the governor of the Straits Settlements, Robert Ibbetson, Owen said: ‘I could not treat as pirates any against whom no acts of piracy had been specifically alleged, or proof obtained.’Footnote 36 A few years later the commander of a British gunboat in the Strait of Malacca, Sherard Osborne, likewise contested the East India Company’s labelling of a fleet of forty Malay war-prahus as piratical:

This fleet of prahus, styled by us a piratical one, sailed under the colours of the ex-rajah of Quedah; and although many of the leaders were known and avowed pirates, still the strong European party at Penang maintained that they were lawful belligerents battling to regain their own.

The East India Company and Lord Auckland, then governor-general of India, took however an adverse view of the Malay claim to Quedah, and declared them pirates, though upon what grounds no one seemed very well able to show.Footnote 37

In the mid 1830s, however, the efforts to suppress piracy were stepped up, henceforth leaving little room for second thoughts as to who was a pirate and who was not. These renewed efforts had not only to do with the continued threat from piracy to the colony’s commerce or the improved intelligence about the whereabouts and modus operandi of the perpetrators: it also gained strength from an Act, passed by Parliament in 1825, for encouraging the capture or destruction of piratical ships and vessels. The Act was originally passed for the purpose of suppressing piracy in the Caribbean during the Latin American wars of independence.Footnote 38 Most importantly in the present context, however, the Act established the practice of paying head money for the killing, capturing or dispersing of pirates:

[T]here shall be paid by the Treasurer of His Majesty’s Navy … unto the Officers, Seamen, Marines, Soldiers, and others, who shall have been actually on board any of His Majesty’s Ships or Vessels of War, or hired armed Ships, at the actual taking, sinking, burning, or otherwise destroying of any Ship, Vessel, or Boat, manned by Pirates or Persons engaged in Acts of Piracy … the Sum of Twenty Pounds for each and every such piratical Person, either taken and secured or killed during the Attack on such piratical Vessel, and then the Sum of Five Pounds for each and every other Man of the Crew not taken or killed, who shall have been alive on board such Pirate Vessel at the beginning of the Attack thereof.Footnote 39

The Act did not require any adjudication of the criminality of alleged pirates, and killing them, rather than capturing or dispersing them, obviously facilitated the procedures for claiming the bounty, as there would be no one alive to dispute the accusation of piracy. Moreover, the stipulation that the reward for killing alleged pirates was four times that of dispersing them obviously encouraged the use of lethal violence and contributed to the brutality of British efforts to suppress piracy in Southeast Asia and elsewhere during the 1830s and 1840s.

The Act was not immediately implemented in Southeast Asia after it was passed in 1825, probably because of uncertainty about whether it was applicable in Asian waters and with regard to personnel serving on board the vessels of the East India Company. In 1836, however, a naval encounter with a fleet of alleged Malay pirates set a precedent.Footnote 40 The British frigate HMS Andromache encountered three prahus with about a hundred Malays from the Lingga Archipelago. A Scottish officer, Colin Mackenzie, who was on board ship as a passenger, described what happened after the British had fired their cannons and hit the Malay boats:

The whole crew having in their desperation jumped into the sea, the work of slaughter began, with muskets, pikes, pistols, and cutlasses. I sickened at the sight, but it was dire necessity. They asked for no quarter, and received none; but the expression of despair on some of their faces, as, exhausted with diving and swimming, they turned them up towards us merely to receive the death-shot or thrust, froze my blood.Footnote 41

A claim was subsequently submitted to the Admiralty for head money, and in following year the Admiralty paid £1,825 to the crew of the Andromache for defeating the alleged pirates. Remarkably, the bounty was paid despite the fact that nine alleged pirates, who were taken prisoner in the encounter, were acquitted of all charges because there was no evidence that they had undertaken or planned to undertake any act of piracy when they were attacked by the British. The advocate-general in Calcutta also noted that the Malays had not fired at the British before they were attacked by the Andromache, thus implying that the alleged pirates had in fact acted in self-defence.Footnote 42

Another problematic circumstance (not raised by the advocate-general) was that, even if the three prahus had indeed been piratical, as defined by the British, only about one-third of those on board were likely to have been raiders or warriors. The majority of people on board a Malay prahu used for war or raiding were normally slaves, prisoners or hired hands whose task it was to row the boat and wait upon their masters.Footnote 43

The risk of killing innocent people was obviously even greater when the British, soon after the massacre witnessed by Mackenzie, intensified their antipiracy campaigns and began to attack whole villages suspected of harbouring piratical persons. The main advocate for this policy was James Brooke, who was able to enlist the support of the Royal Navy in his campaigns against alleged pirates on the coast of north Borneo. Consciously stretching the definition of piracy and arguing that piracy in Asia was fundamentally different from European piracy, Brooke, in a memorandum of 1844, urged the British government to burn and destroy all pirate haunts and disperse the pirate communities in order to eradicate the evil from the Malay Archipelago. The methods recommended by Brooke were diligently implemented during the remainder of the 1840s.Footnote 44

The apparent discrepancy between, on the one hand, piracy in the legal sense of the word and, on the other, an allegation of piracy as a basis for claims to head money was resolved after a fashion by the High Court of Admiralty in 1845. In the so-called Serhassan case, named after a small island, Serasan, off the coast of northwest Borneo, where around thirty alleged pirates were killed and another twenty-five captured by a British naval expedition in 1843, the court ruled that the bounty claimed by those involved in the encounter was due, despite the lack of positive evidence that those killed or defeated were in fact pirates. In the opinion of High Admiralty judge Stephen Lushington, it was sufficient ‘to clothe their conduct with a piratical character if they were armed and prepared to commence a piratical attack upon any other persons’.Footnote 45

In the twelve years between 1836 and 1847 altogether £20,435 were paid for over 1,000 killed or (more rarely) captured Malay pirates, and £12,675 for some 2,500 dispersed pirates in Southeast Asian waters. During this time, the head money claimed from engagements in the Strait of Malacca and on the north coast of Borneo made up the bulk – more than 80 per cent − of total British payments for the capture and destruction of pirates worldwide.Footnote 46 The Admiralty, which paid the bounties, seemed to be of the opinion that if piracy was to be exterminated in the Malay Archipelago, there was little room for arguing about whether or not an attack had been justified or whether those killed were in fact pirates or innocent fishermen or traders.Footnote 47 Racial classification thus overrode other concerns, such as those pertaining to humanity and the rule of law, all under the colonial ‘logic of the disposability of human life in the name of civilization and progress’, as in another context Rolando Vazquez and Walter Mignolo put it.Footnote 48

The antipiracy operations and the brutality used in them were controversial, however. In London, anti-imperialist politicians and humanitarian activists began to question the sweeping use of the term piracy in the Southeast Asian context and raised questions about who should be held responsible for the maritime violence and what the appropriate response of the British authorities should be. In particular, the brutal campaigns of James Brooke against the allegedly piratical communities of north Borneo began to draw sharp criticism in the press and in Parliament toward the end of the 1840s. Brooke was criticised, among other things, for designating as piracy what was actually intertribal warfare.Footnote 49 He was also chastised for the harsh measures employed to deal with the alleged pirates and the large-scale destruction of human life and property. With reference to the so-called Battle of Batang Marau in 1849, in which several villages were burned and some 500 alleged pirates killed, the Radical Member of Parliament Richard Cobden said: ‘The loss of life was greater than in the case of the English at Trafalgar, Copenhagen, or Algiers, and yet it was thought to pass over such a loss of human life as if they were so many dogs; and, worse, to mix up professions of religion and adhesion to Christianity with the massacre.’Footnote 50

The mass slaughter at Batang Marau led to a renewed effort to repeal the already criticised Bounty Act, a move that had begun a few years earlier, both for humanitarian and financial reasons. When the government, in 1850, demanded over £100,000 from Parliament to satisfy claims for head money – mainly for engagements in the South China Sea, but also including £20,700 for the 500 pirates who were killed and another 2,140 who were dispersed at Batang Marau – the process of changing the law was reinitiated.Footnote 51 The Act was repealed in 1850, although the practice of paying head money – now renamed ‘prize money’ – continued until 1948.Footnote 52

While Brook and the Royal Navy campaigned against alleged pirates in north Borneo, piratical activity in the Strait of Malacca declined sharply, particularly during the second half of the 1840s. Between 1846 and 1849 there were only three reported attacks against British vessels committed by Malays or Dayaks, compared with twenty-two between 1840 and 1845: that is, a decline of 80 per cent on a yearly basis.Footnote 53 By the 1850s organised Malay piracy had ceased to be a security threat in the Strait of Malacca, even though occasional acts of petty piracy and coastal raiding continued to occur.Footnote 54

It is doubtful to what extent the massacres of the 1830s and 1840s were responsible for the decline in piratical activity toward the middle of the century. John Crawfurd, who in 1825 had recommended that the most noted pirate haunts be destroyed by way of example, now advised against such methods:

The destruction of the supposed haunts of the pirates by large and costly expeditions, seems by no means an expedient plan for the suppression of piracy. In such expeditions the innocent are punished with the guilty; and by the destruction of property which accompanies them, both parties are deprived of the future means of honest livelihood, and hence forced, as it were, to a continuance of their piratical habits. The total failure of all such expeditions on the part of the Spaniards, for a period of near three centuries, ought to be a sufficient warning against undertaking them.Footnote 55

By contrast, Dutch efforts to suppress piracy, particularly in the Riau Archipelago, were of greater consequence. From the 1840s, the Dutch began to take firmer control over the Riau Archipelago, where most of the pirates were based, administratively, economically and militarily. The Dutch also began, on a limited scale, to promote indigenous trade as a means of weaning the Malay elites from engaging in or sponsoring piracy and to encourage them to take active part in the efforts to suppress piracy. The Dutch also intensified conventional antipiracy patrols, and, with improved intelligence and enhanced naval capacity, they were able to capture many of the perpetrators, often at their landbases. Thus deprived of their safe havens and protection from local rulers and strongmen, the pirates had little choice but to withdraw to more remote locations in the archipelago, or to take up other occupations.Footnote 56

For the Dutch in the Strait of Malacca, like the Spanish in the Sulu Archipelago, it was of key importance to assert their sovereignty or hegemony over Sumatra and the Riau Archipelago by preventing maritime violence from emanating from Dutch territory or spheres of influence, and to affect British interests or international commerce. These concerns came to the fore in the early 1840s, when British naval vessels engaged in antipiracy operations violated Dutch territory on several occasions. In 1841, moreover, the British announced that they were considering abrogating the 1824 Treaty of London because of alleged commercial discrimination by the Dutch. By efficiently suppressing piracy emanating from its territory, the Dutch sought to alleviate the risk of further British intervention in the Dutch sphere and to weaken support for a more expansionist British policy in the Straits Settlements.Footnote 57

Chinese Piracy

As the depredations by Malay pirates declined in the Strait of Malacca in the 1840s, a new type of piracy appeared, which soon came to constitute an even greater threat to the indigenous trade of the Straits Settlements than the earlier form. This new type of piracy was directly linked to social and political developments in China and the South China Sea. The Qing Dynasty enlisted large numbers of Chinese junks as armed privateers in the Opium War (1839–42) against the British, and after the end of the war many of them took to piracy. The Chinese authorities had little will or capacity to check the depredations of the pirates, most of whom were based in or around the major trading centres of southern China, such as Canton (Guangzhou), Hong Kong and Macau. Firearms and munitions were readily available in these ports, and the pirates could also easily acquire provisions and dispose of their booty there. The British authorities in Hong Kong were notoriously corrupt and inefficient in the colony’s early years, and local officials at times even colluded with the pirates.Footnote 58

The first reports of Chinese junks committing piracy in the Strait of Malacca in the 1840s led the Straits authorities to increase antipiracy patrols. There was no permanent British naval base in the region, however, and the colonial government itself had very limited ability to combat piracy. For most of the time there was only one British colonial steamer available for antipiracy operations in the Strait of Malacca. Piracy nevertheless declined in the second half of the 1840s – largely, as we have seen, as a result of the measures taken by the Dutch in Sumatra and Riau – which led the British to believe that their own efforts were sufficient to check both Chinese piracy and the depredations of the Malay raiders based in and around the Strait of Malacca.Footnote 59

The decline in piratical activity in the second half of the 1840s was temporary, however, and once again events in China spilled over into Southeast Asia. In 1849 pirates from southern China robbed a junk belonging to a British subject and killed two British officers off the south coast of China, which led the Royal Navy to step up antipiracy operations in the South China Sea. At least in part as a result of these and subsequent naval operations, some of the perpetrators moved their operations to Singapore and the Malay Archipelago.Footnote 60 The upheaval of the Taiping Rebellion in southern China, which broke out in 1850, further contributed to the surge in piracy on the South China coast and in the major rivers of southern China. Pirates soon extended their operations further to the western parts of the South China Sea, including the waters off Vietnam, Cambodia, and the Gulf of Thailand. By the mid 1850s heavily armed junks also preyed on maritime commerce in the waters close to Singapore and in the Strait of Malacca.Footnote 61

On average there were between one and two cases of piracy every month reported to the police in the Settlements between 1855 and 1860, with Singapore making up for more than half, or forty-nine out of a total of eighty-nine reported cases, followed by Penang with around 40 per cent, or thirty-six reported cases.Footnote 62 These figures, based on the number of cases reported to the Straits Settlements police, were only a fraction of the total number of pirate attacks committed, however, a circumstance of which the authorities were well aware.Footnote 63 Frequently none of the victims survived to report an attack to the police, and even if there were survivors, many attacks that occurred outside the jurisdiction (that is the ports and territorial waters) of any of the three settlements went unreported. Moreover, because of cultural differences and language barriers, it is likely that many victims of non-European nationality did not report attacks to the police. The local press, by contrast, was rife with horrific stories of piracy, and the Singapore newspapers featured reports of pirate attacks nearly every week for most of the 1850s.Footnote 64

The main targets of the junk piracy were the small trading junks that plied the South China Sea between Singapore and Cochinchina (southern Vietnam). Unarmed or lightly armed junks carrying various types of cargo, such as opium, textiles, livestock and agricultural products, were boarded and robbed at sea, both in the waters near Singapore and along the east coast of the Malay Peninsula, and further to the north, in the waters around southern Vietnam and Cambodia. The level of violence varied depending on the modus operandi of the perpetrators and whether or not the victims offered resistance. Many attacks involved the use of indiscriminate and lethal violence.Footnote 65

The depredations had a visible impact on the maritime trade between Singapore and Cochinchina. According to the Singapore Chamber of Commerce, the attacks brought about a sharp decrease in that trade in the junk season of 1853, an impression that is corroborated by official statistics. Between the fiscal years 1850−51 and 1853−54 the total number of junks arriving from or departing for Cochinchina declined from 255 to 156, that is, by close to 40 per cent.Footnote 66 According to contemporary newspaper reports, only half of the Asian vessels bound for Singapore from the east managed to reach their destination in 1854.Footnote 67

The decrease, however, was not evident in the aggregate trade statistics for Singapore: the value of the total registered imports and exports of Singapore in fact increased by 46 per cent between the fiscal years 1851–52 and 1853–54. The volume of trade with other parts of Asia was not affected by the piratical activity, and the number of junks arriving from and departing for China and Siam increased substantially between the two fiscal years.Footnote 68 Moreover, the share of trade carried by square-rigged vessels – which in general were larger and more heavily armed than the small trading junks – increased and compensated for the decline in the junk trade.Footnote 69

The Straits government received little support from Calcutta with regard to gunboats or other resources needed to suppress piracy. In 1855 the merchants of Singapore sent petitions to the governor-general of India, the Royal Navy and both Houses of Parliament, asking for naval protection and improved legislation to deal with the problem of piracy, but with no result.Footnote 70 Calcutta’s apparent lack of interest in the maritime security and commerce of the Straits Settlements fed into a long-standing and widespread discontent in the colony with being subordinated to the English East India Company in India. In a petition to Parliament in 1857 a number of merchants complained – among a host of other things − about the failure of the company to take the problem of piracy in the Strait of Malacca seriously:

From the very first establishment of Singapore the trading vessels, and more especially the native craft, resorting to it, have been much exposed to the attacks of pirates. No systematic measures of protection have ever been adopted or carried out by the East India Company, who have been content to leave the service to be performed by the Royal Navy. Her Majesty’s Naval forces being liable to be called away to other duties, can only act at intervals; and hence for long periods the neighbouring Seas have been left wholly or very slightly guarded and have at such times swarmed with pirates, to the great injury of the trade of this port.Footnote 71

In view of the great risks of travelling by sea, many trading junks and other vessels were heavily armed with spears, swords, handguns, cannons and other weapons. According to the authorities, by the mid 1850s virtually all vessels leaving Singapore were heavily armed and appeared to have the means of committing piracy, but it was impossible to know whether they were armed for that purpose or for protection. Often the only times the authorities could be certain were in the rare instances when pirates were caught red-handed committing a piratical attack at sea.Footnote 72

The problem of identifying the pirates was not limited to the sea but was as pertinent on land. Singapore was in many respects an excellent base for fitting out and launching pirate expeditions, a circumstance that was frequently noted by contemporary observers.Footnote 73 In its early years, Singapore was even reputed to be a market for slaves captured by the Iranun and other raiders in Southeast Asia, despite the British commitment to the abolition of the slave trade.Footnote 74 By the middle of the century the Dutch resident in Riau, located just across the Singapore Strait, claimed that pirates had become both more deplorable and more frequent in Singapore than in Riau – which, as we have seen, until recently had reputedly been a pirate nest in the region – and that pirates based in both Singapore and Riau obtained their arms and munitions in British ports and sold their booty or exchanged it for ammunition there.Footnote 75

Like Hong Kong in eastern Asia, Singapore was a major market for arms in Southeast Asia, and firearms and munitions were readily available for purchase. Moreover, there were no restrictions on the amount of armaments that a vessel could carry without being formally suspected of being a pirate vessel. The trade in arms was not regulated, and the importation of arms from Europe was an important part of the city’s commerce. For example, in 1855, according to official figures, 3,659 iron guns, 15,259 muskets and 2,559 pairs of pistols were exported to Singapore, only from British and Dutch ports.Footnote 76 These figures did not include numerous unreported shipments of munitions. According to the governor of the Straits Settlements, Edmund Blundell, there was scarcely a mercantile firm in Singapore, regardless of nationality, that did not import large and small arms, military stores and ammunition.Footnote 77 Most of the arms were re-exported, particularly to China, where demand for arms and munitions was high because of civil unrest. Many weapons, however, also ended up on board pirate junks operating out of Singapore.

Besides the ready supply of arms, there were several other reasons Singapore was an excellent base for piratical operations. Unscrupulous crews could easily be hired, and information about the routes and cargoes of potential victims was easy to come by. Pirates could obtain passports and other papers from the Straits authorities by which they could pass themselves off as honest traders if they were visited by British, or any other nation’s, vessels at sea. As a port of free trade, Singapore was also a good place for the pirates to dispose of their booty with little risk of questions being asked about the provenance of the goods. As there were no tariffs or duties on imports or exports, there was little incentive or interest on the part of the authorities to keep records of the goods that changed hands, legally or illegally. The police, consequently, generally lacked the means by which to investigate reported cases of piracy through tracking down suspicious goods.Footnote 78

The police sometimes searched suspected pirate junks in port, particularly those with heavy, offensive armaments and little cargo on board, but even when the indications of piratical intent were strong, there was little the authorities could do to stop the suspected marauders from setting out to sea. A police report from 1856, for example, gives the following account of an investigation in Singapore Harbour, which was conducted after rumours had reached the police that pirate vessels were being fitted out:

Junk No. 171 has twenty-three large Guns, most of them mounted; twenty-four Casks Gunpowder; number of Chinese Spears and Swords; a large quantity of shot, both small and large, with 13 Chests of Opium … This Junk looks very suspicious; she is apparently a fast sailer, and with her large armament, would take, with ease, any Junk or Vessel that came in her way.

Junk No. 145 has thirty Guns, that is eleven large and nineteen small, all well mounted. She has also, in her hold, four very large Guns; they are lying right down in the centre of the hatch, and can easily be got up when wanted. Her powder is thirty-two piculs, with a large number of Shot of all sizes. Her cargo consists of sixteen Chests of Opium, Gambier and Shells in bags, with some empty boxes, and is ballasted with sand.

Junk No. 143 has fourteen Guns, nearly all large; forty kegs Gunpowder; a number of Boarding Pikes or Spears, and a large quantity of shot …

The whole of the Junks mentioned have a very suspicious-looking appearance. At present they have but few men on board, but when they are about to leave to proceed to Sea, they generally take in a large number.Footnote 79

The rudders were removed from the three suspected junks in order to prevent them from sailing, but they were returned after a few days because no proof could be presented of their intention to commit piracy. The owners of the junks, according to the report, ‘of course, naturally argued that the armament was designed solely for defence’.Footnote 80

Governor Blundell advised his superiors in Calcutta to pass new legislation in order to enable the authorities to take effective measures against the pirates. One of his proposed measures was to give the Straits authorities the right to detain in port suspect pirate vessels without the need to present concrete evidence of piratical intent.Footnote 81 The suggestion was controversial for the ‘stretch of authority’ that risked not only being inefficient but also bringing the government and the police into public contempt, as the Singapore Free Press opined.Footnote 82 Two years later a version of Blundell’s suggestion was nonetheless passed into law in the form of the Indian Act XII of 1857 (Ordinance No. 7) on ‘Piratical Native Vessels’. The Act stated that a native vessel could be seized and detained for up to six months by the authorities if there was reasonable cause to suspect that the vessel in question was a ‘piratical vessel’, ‘belonged to pirates’, ‘intended to be used for piratical purposes or for the purpose of knowingly trading with or furnishing supplies to pirates’. The authorities were also invested with the power to order measures to prevent a vessel from going to sea if it was ‘manned, armed, equipped, furnished or fitted out’ in a manner deemed ‘more than sufficient for the due navigation and protection thereof as a trading vessel’.Footnote 83

The Act, however, did little to check the problem of piracy emanating from Singapore. In 1858, just like five years earlier, the authorities had to release six heavily armed junks, all of which had been detained on suspicions of piratical intentions under the Act. The junks were released after some ‘Chinese merchants and shop-keepers of decided respectability’ in Singapore had come forward and certified that the junks were peaceful traders.Footnote 84

The law was in many respects a half-measure, and two of Blundell’s more controversial suggestions in order to curb piratical activity around and emanating from the Straits Settlements were not adopted. One was the suggestion that the steamers and gunboats of the colonial government be given the right to visit, search and seize any suspect vessel, regardless of nationality, on the high seas. The governor argued for the legalisation of the ‘apparently arbitrary seizures’ which he believed were necessary, and he proposed that a powerful steamer, commanded by a ‘young and active commander, manned by Malays and not encumbered with naval discipline and etiquette’, nor with ‘Common Law definitions of piracy’ or the Admiralty’s instructions to Her Majesty’s Ships, be despatched to clear the Straits Settlements and its neighbourhood of all piratical vessels.Footnote 85 The suggestion was rejected by the Indian Government, however, on the grounds that it was beyond the colonial government’s power to legislate on matters relating to the high seas and the law of nations.Footnote 86

Although the governor failed to obtain legal sanction for some his proposed measures, antipiracy patrols and search operations were eventually stepped up in order to suppress Chinese piracy. British vessels in the area – both the colonial steamers and the gunboats of the Royal Navy – interpreted their right to visit, search and seize suspected pirate vessels on the high seas generously. The antipiracy operations began to bear fruit toward the end of the 1850s. In May 1858 the colonial steamer Hooghly captured two suspected junks and brought them to Singapore, and in May the following year the Royal Navy’s corvette Esk captured another two piratical junks, after they had managed to fight off the Hooghly. In each case there were about fifty Chinese on board, all of whom were convicted and sentenced to transportation to Bombay.Footnote 87

Perhaps the most controversial of Blundell’s suggestions was to curb the free trade in munitions (but not in arms) in the Straits Settlements, a trade that obviously stimulated piracy, not only in the Strait of Malacca and the Malay Archipelago in general, but also in China and the South China Sea. The problem was that the trade was extremely profitable and a cornerstone of the commercial success of the Strait Settlements. After the founding of the colony in 1826, the English East India Company had been given virtually free rein to trade in arms, even though there were strong concerns already at the time about the risk that arms and munitions that passed into Asian hands might be used in uprisings and piratical attacks. The company was nonetheless licensed to supply munitions to Asian buyers, but only in ‘deserving’ cases, including to indigenous rulers who ventured to suppress piracy and other disturbances in their territories. The scope of the licence was lavishly interpreted, however, and the second half of the 1820s saw an explosion in the colony’s arms trade, which in turn fuelled the increase in piratical activity in the region at the time. In 1828 an attempt was made to restrict the arms trade in and out of Singapore, but the Board of Commissioners for the Affairs of India in London decided to abandon the attempt after protests from Singapore merchants. The argument was that the restrictions were useless because munitions were readily available in the archipelago from American and French traders.Footnote 88

As thirty years earlier, thus, Blundell’s suggestion to restrict the Singapore arms trade did not meet with approval, neither in the Straits Settlements nor in London or Calcutta. It was obviously deemed more important from the colony’s and Britain’s point of view that the lucrative trade continue to prosper than to curb the proliferation of arms that fuelled piratical activity. Free trade, in other words, took precedence over maritime security.

When the export of arms eventually was regulated, in 1863, it was not primarily for the purpose of discouraging piratical activity but mainly for the purpose of preventing wars and major uprisings directly affecting British interests in Asia. Concerns over such disturbances were aggravated, particularly in the wake of the Indian Rebellion (1857–58) and the Second Opium War (1856–60) in China, both of which involved armed violence against British citizens and interests.Footnote 89

After 1860, junk piracy in the Straits largely subsided for several reasons. The arrest of two of the major bands of Chinese pirates operating out of Singapore in 1858–59 was of some consequence, but of greater importance were the political developments in China, particularly the end of the Second Opium War in 1860 and the defeat of the Taiping Rebellion in 1864. Around the same time China and Britain agreed to cooperate in the suppression of piracy and China agreed to support British warships in pursuit of pirates within Chinese territory.Footnote 90 From the 1860s the Chinese authorities also began to take more decisive measures to suppress piracy in and emanating from their territory as part of a broader attempt at the time to strengthen and modernise the military and civil administration. Taken together, these developments brought about a decline in Chinese piracy in the Strait of Malacca.

Chinese piracy did not disappear from Southeast Asia, however. Squeezed between the antipiracy operations of the Chinese, British, Dutch and other colonial powers, both in China and the South China Sea, and in the Malay Archipelago, Chinese pirates increasingly took refuge in the Gulf of Tonkin, where, as we shall see, they continued to wreak havoc.

‘Highway Robbery at Sea’

Although Malay piracy had declined in the 1840s, it continued on a smaller scale far beyond the middle of the century, and it would, in the estimation of John Crawfurd, be as hopeless to exterminate it as it would be to put an end to ‘burglary and theft in the best ordered states of society’.Footnote 91 An unintended consequence of the increased Dutch control over Riau was that many of the pirates moved and dispersed to various locations around the Strait of Malacca. Attacks thus continued to occur, not only in the vicinity of Singapore and in the southern parts of the Strait, but also along the east coast of Sumatra and along the west coast of the Malay Peninsula.

Although they were less serious than the acts of Chinese piracy, the depredations of Malay pirates were a nuisance to traders and colonial officials in both the British and the Dutch colony. These were difficult to suppress, moreover, because information about the hideouts of the perpetrators was difficult to come by, and large expeditions were for the most part inefficient against the scattered pirates. When detected red-handed, the perpetrators of an attack were often able to make a swift escape into one of the many small rivers and creeks of the Malay Peninsula or Sumatra, where the large colonial steamers and gunboats could not follow them because of their deep draft. Cruising against the pirates was also difficult because of problems of recognition and, interpretation, and, while at sea, pirates were often indistinguishable from traders or fishermen.Footnote 92

Many petty pirate attacks occurred in the vicinity of Singapore in the late 1850s and early 1860s. The perpetrators generally used small, inconspicuous boats, such as Malay sampans (small, flat-bottomed boats, usually with a shelter on board) and they tended to carry only light and inconspicuous armament, such as muskets and cutlasses. In contrast to the heavily armed pirate junks that were equipped with cannons, stinkpots, boarding pikes and other offensive weapons, there was thus little about the piratical sampans that a priori indicated criminal intent. Another circumstance that favoured the operations of the pirates was that they were able to dispose of their plunder quickly and in ways that were difficult for the authorities to detect. The loot from pirate attacks in British waters or against British vessels was often carried off to neighbouring islands beyond the jurisdiction of the British.Footnote 93

This type of ‘highway robbery’ at sea, as it was labelled in an official report, was not a security threat to the Straits Settlements, and its frequency was not so great as to have a serious impact on trade in and out of the colony.Footnote 94 At the same time, however, the attacks were often violent and brutal. In several instances they involved the murder of the victims, even when they did not offer resistance. In the year between May 1859 and April 1860, for example, eight people were reportedly murdered by Malay pirates in various locations around the Straits colony.Footnote 95

According to newspaper reports one particular gang of Malay pirates, based in the Riau Archipelago and led by a man from the island of Galang, Pak [Pah] Ranti, was responsible for the attacks. For several years Pak Ranti managed to avoid capture by the Straits Settlements police, despite several close brushes. In 1859, he attacked a police boat with a crew of six men and a Malay officer, killing the officer and three of the policemen, an event that led the police to intensify their efforts to defeat the band.Footnote 96 A series of unsuccessful operations and fruitless chases, accompanied by false reports of Pak Ranti’s capture or defeat, however, led the police to be chastised in the Singapore press for its alleged incompetence and overzealous efforts in pursuing pirates. The Straits Times, in an editorial, argued that pirate-hunting seemed to be a ‘pleasant and exciting [occupation] with a touch of [the] romantic about it’ and that it too readily distracted the police from their ‘dull routine duties’.Footnote 97 Such views demonstrated the extent to which piracy by the early 1860s had been desecuritised and was no longer seen as a major threat to the commerce and prosperity of the Straits Settlements, despite the violence and the risk that the attacks posed to local traders and fishermen.

If chasing pirates could be described as a romantic pursuit, there seems to have been little that was romantic about being a Malay pirate at the time. A captured member of Pak Ranti’s gang confessed in 1861 to having been a pirate for three years, earning only his food and getting no share of the spoils. He and his comrades were frequently chased by the police and forced to hide in the jungle for several days. On several occasions members of the band were killed and their boats captured. Sometimes they lacked food, and most of the village chiefs in Riau, where the pirates were based, would have nothing to do with them.Footnote 98 This testimony shows the extent to which piracy and maritime raiding, in only a couple of decades since the mid 1840s, had ceased to be an attractive or even feasible occupation in and around the Strait of Malacca.

The Straits Settlements police, aided by the Raja of Johor, who was on friendly terms with the British, eventually succeeded in bringing the ravages of Pak Ranti to an end through their relentless pursuit of the pirates and the issue of a reward for any information that would lead to the capture of the pirate chief. At the end of 1861, he gave himself up to a local chief in Riau who was loyal to the Dutch. The reason, according to the British report, was the continual harassment that he and his followers had suffered for several years at the hands of the police.Footnote 99

Following the capture of Pak Ranti the number of piracies reported to the Straits Settlements authorities declined, and only a few isolated attacks on small native crafts, most of them of a trifling nature, were reported in the following years.

In the long term, the successful suppression of small-scale Malay piracy in and around the Straits Settlements was in large part due to a new strategy on the part of the authorities. Regular patrols were launched, not only in the territorial waters of the Settlements and in the vicinity of its ports, but also along the coast of the Malay Peninsula. Tonze, a former so-called penny ferry, which previously had been used to carry passengers on the Thames in London, was brought to the Straits Settlements and converted to a gunboat. She was attached to Melaka and employed to patrol the west coast of the Malay Peninsula and its many rivers and estuaries in order to deter any piratical activity.Footnote 100 Another, similar, vessel, the Mohr, was attached to Penang. Despite some initial doubts about the suitability of the penny ferries for military or law enforcement purposes, they proved able to perform their duties efficiently. They drew little water, which enabled them to cross the bars that existed at most river mouths in the peninsula and thus penetrate far into the interior, thereby making it more difficult for the pirates to elude pursuit by seeking shelter upstream.Footnote 101

As a result of these efforts petty piracy could finally be effectively checked, and in 1864–65 only one incident was reported in British territorial waters, probably the lowest since the founding of the Straits Settlements almost forty years earlier. Outside the British jurisdiction, however, deadly pirate attacks continued to occur occasionally, as attested by the discovery of the dead bodies of three Siamese, who evidently had been murdered at sea, on the shore near Kuala Buka in Terengganu in 1865.Footnote 102

Resurgence of Piracy in the North

The lull in piratical activity turned out to be temporary. From the end of the 1860s small-scale piratical activity resurged, now in the northern parts of the Malay Peninsula between Penang and Melaka. As earlier, many attacks went unreported by the colonial authorities because they occurred outside the British (or Dutch) jurisdiction. However, to the extent that the attacks befell British subjects – including merchants, shipowners, crew and passengers residing in the Straits Settlements but not necessarily of British nationality – or were attended with murder, the piracies were brought to the attention of the authorities as well as the general public.

The renewed wave of piracy was linked to the social and political upheaval in the Sultanates of Perak and Selangor. Initially it seemed that most of the pirates came from Perak in connection with an ongoing conflict over the control of the tin-mining district of Larut in Perak. After civil war broke out in Selangor in 1866, however, the main theatre of piratical activity in the Strait of Malacca seemed to shift, and Selangor soon gained a reputation among the British for being the most formidable pirates’ nest in the region.Footnote 103

The background to the unrest in Selangor was a dispute between two of the country’s leading chiefs, Raja Abdullah and Raja Mahdi, over the control and taxation rights in the district of Klang in western Selangor. Both sides kept boats in the Strait of Malacca, off the coast of Selangor, by means of which they tried to cut off the communications and supply lines of the other side. In that context, some trading vessels from Melaka became victims of minor acts of plunder. Such incidents occurred with relative frequency, but they were for the most part relatively insignificant and did not involve the murder of crew and passengers.Footnote 104

To the British the piratical activity emanating from Perak and Selangor seemed qualitatively different from the petty piracy that had taken place in the waters off Singapore a few years earlier. The new type of piracy appeared to be organised and sponsored by leading Malay chiefs, whose allegiance to the Sultans of Perak and Selangor, respectively, was but nominal. From the British perspective the chiefs seemed to believe that their rank gave them the right to rob and molest seafarers with impunity and that doing so could even be considered an honourable occupation. John McNair, a British colonial official who served in Singapore at the time, wrote with reference to Perak that ‘piracies are, for the most part, chieftain-like raids. There is no petty thieving, but bold attacks upon vessels by men who seem to have considered that they had a right to mulct the travellers on the great highway of the sea at their will’.Footnote 105

The resurgence of piracy in Perak and Selangor in the second half of the 1860s seemed, in this sense, to resemble traditional maritime raiding in the region, which was seen by the perpetrators – but not necessarily by the victims or the Malay population in general − as a legitimate and even honourable pursuit. Raja Mahdi was a particular scapegoat in British eyes, who was made out to be a pirate and a thoroughly bad character. At the same time, however, the British had reports that he was admired by his followers as a courageous and chivalrous ‘Malay warrior of the old school’, as Richard Wilkinson, a British colonial official and historian, put it.Footnote 106

What was at stake for the British was not only the suppression of piracy and security for maritime traffic and commerce: British investors also looked at the Malay Peninsula with a view to exploiting the economic opportunities provided by the booming tin industry and other natural resources. The unstable political situation in Selangor and Perak was aggravated by the influx of rival Chinese societies involved in tin-mining. Political instability was thus increasingly seen as an obstacle to the economic interests of British and other businessmen based in the Straits Settlements. Toward the end of 1860s the traditional noninterventionist policy that the Indian government had adhered to in the region since the establishment of the Straits Settlements began to be regarded as obsolete by leading officials and merchants in the colony. Moreover, the case for a more expansionist British policy was strengthened by the rise of Germany as an imperial power and fears that the Germans might try to establish a naval station in the region.Footnote 107

Against that background, the acting governor of the Straits Settlements, Colonel Edward Anson – who substituted for Governor Harry Ord, on leave at the time − took the initiative to appoint a committee to report on the colony’s relations with the Malay states. The report, dated 19 May 1871, recommended the introduction of a residential system modelled on that used for indirect British rule in India. A British resident (or ‘political agent’) was to be appointed to the Malay Sultanates who would advise the Sultans on all policy matters of concern to the British, which, in principle, included everything except questions related to Malay religion and custom.Footnote 108

In London, however, the Liberal government, led by Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone, continued to maintain the policy of nonintervention, leaving little room for the Straits government – especially under the aegis of an acting governor − to exercise any influence over the developments in Perak and Selangor. For those in the colony who favoured a more interventionist policy, such as Anson, a resurgence in piratical activity in or emanating from the two states could be regarded as a welcome development that might provide the pretext for an intervention.Footnote 109

The Selangor Incident

In June 1871 a particularly gruesome pirate attack, in which thirty-four men, women and children were murdered, reportedly took place in the Strait of Malacca. The alleged perpetrators were fourteen Chinese, who boarded the junk Kim Seng Cheong, bound for Larut in Perak, as passengers shortly after its departure from Penang. Apart from the passengers and crew, the junk was said to be carrying a general cargo worth about $7,000, including $3,000 in specie.Footnote 110

The attack on the Kim Seng Cheong – if, indeed, it happened as officially reported − was not just ‘a simple case of piracy’, as put by one historian.Footnote 111 It was the most lethal and ruthless known pirate attack in the Strait of Malacca for several decades, and it happened at a time when piratical activity seemed, once and for all, to have subsided. For nine months before the attack there had been no acts of piracy reported at all in the Straits Settlements.Footnote 112 As the attack on the Kim Seng Cheong befell a ship owned by a Chinese firm based in the British colony, and as the perpetrators had boarded the junk in the vicinity of a British port, governor Anson saw it as his duty to take action in order to apprehend the perpetrators and, if possible, recapture the junk and its cargo. At the same time, however, Anson’s handling of the affair must also be understood against the background that he, like many other leading officials in the Straits Settlements, took a great personal interest in the problem of piracy and that he was in favour of a more interventionist colonial policy with regard to the Malay states.Footnote 113