Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Preface

- List of Abbreviations and Acronyms

- List of Illustrations

- PART I Essays

- Overview

- Introduction: A Centenary History of Abantu-Batho, the People's Paper

- Chapter 1 ‘Only the Bolder Spirits’: Politics, Racism, Solidarity and War in Abantu-Batho

- Chapter 2 ‘They Must Go to the Bantu Batho’: Economics and Education, Religion and Gender, Love and Leisure in the People's Paper

- FOUNDERS AND EDITORS

- THEMES AND CONNECTIONS

- PART II Anthology

Introduction: A Centenary History of Abantu-Batho, the People's Paper

from Overview

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 21 April 2018

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Preface

- List of Abbreviations and Acronyms

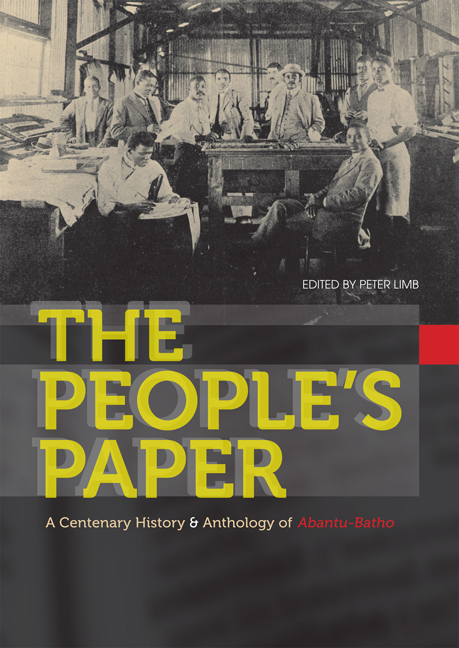

- List of Illustrations

- PART I Essays

- Overview

- Introduction: A Centenary History of Abantu-Batho, the People's Paper

- Chapter 1 ‘Only the Bolder Spirits’: Politics, Racism, Solidarity and War in Abantu-Batho

- Chapter 2 ‘They Must Go to the Bantu Batho’: Economics and Education, Religion and Gender, Love and Leisure in the People's Paper

- FOUNDERS AND EDITORS

- THEMES AND CONNECTIONS

- PART II Anthology

Summary

ABANTU-BATHO: A VERY SHORT INTRODUCTION

The 2012 centenary of the African National Congress (ANC) is also that of the closely allied newspaper, Abantu-Batho (The People). This little-studied weekly was established in October 1912 by the convener of the ANC, Pixley ka Isaka Seme, with financial assistance from the Queen Regent of Swaziland, Labotsibeni. It attracted as editors and journalists some of the best of a rising company of African intellectuals, political figures and literati such as Cleopas Kunene, Saul Msane, Richard Victor Selope Thema, T. D. Mweli Skota, Robert Grendon, S. E. K. Mqhayi and Nontsizi Mgqwetho. In its pages important themes of the day, from the pass laws, Land Act and the World War to strikes and socialism, the founding of Fort Hare, the rights of black women and Garveyism were articulated, just as mundane events such as football matches, marriages and church gatherings were reported. It was also a forum for letters and literary contributions, some of the highest calibre, others of a plebeian bluntness.

A dynamic black press had already been established in some cities and towns by 1912. The ability to spread news in a printed format had once been a virtual monopoly of the colonial state or the missions, but the rise of a black-owned and -edited press challenged this, just as the spread of new communications and news agencies opened up space to share ideas more freely. In the latter-half of the nineteenth century, a nascent African intelligentsia developed letter-writing networks and then, having few publication outlets, created their own regional newspapers such as Imvo Zabantsundu (Native Opinion, 1884–) of J. T. Jabavu, Izwi Labantu (Voice of the People, 1897–1909) of A. K. Soga, Koranta ea Becoana (Bechuana Gazette, 1901–08) and Tsala ea Batho (The People's Friend, 1910–15) of Solomon Tshekisho Plaatje, and Ilanga lase Natal (Natal Sun, 1903–) of John Langalibalele Dube, plus several weeklies printed across the border in Basutoland (now Lesotho). The editorial politics of these weeklies was always strictly within constitutional limits, but in favour of extending black rights. Like Abantu-Batho, their circulation and readership (see below) were modest, but their impact on emergent political bodies was large.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- The People’s PaperA Centenary History & Anthology of Abantu-Batho, pp. 2 - 48Publisher: Wits University PressPrint publication year: 2012