When Japanese and Chinese forces clashed in Shanghai in the early months of 1932, twenty-one-year-old Macau-born Guo Jingqiu (Helena Kuo) was starting a journalism career that would later take her to Britain, France and the United States. The violence of the combat led her to return temporarily to her place of birth, where her family still lived, in search of safety. There, she encountered a completely different reality: ‘I went out into the town that first night. The dancing and gambling and vice continued as usual. The hotels were crowded with rich refugees from Shanghai. Macao seemed more like Babylon than ever. No one worried about China’s war problem.’Footnote 1

Guo was not the only person in Macau concerned about China’s situation, but, in 1932, the Japanese invasion of China was still regarded in the enclave as a distant affair. In 1937, when a continuous state of warfare began, things were very different.

After addressing the limited impact of the Sino–Japanese conflict in Macau in the early 1930s, this chapter explores how the territory came to be an important intersection for competing Chinese forces from 1937 to 1941. It was relevant not only for Chinese resistance activities in Guangdong province – both Nationalist and Communist – but also for the collaborationist movement led by Wang Jingwei. Similarly, Macau was used as a meeting place for Japanese peace feelers towards Cantonese elites and Chiang Kai-shek’s envoys. It was a place that did not simply stand in the middle but was caught in the middle of different and intersecting nationalist and imperialist designs.

The great majority of the Macau population – both pre-war and refugee – was Chinese, so understanding how different Chinese actors perceived and engaged with neutrality and collaboration in the enclave is paramount. Macau was used by both Chinese resistance and collaborators in their activities to maintain China’s war effort against Japan or convince others to file for peace with the occupiers. The commercial and transportation opportunities neutrality offered were amply explored by both those resisting and those collaborating with Japan.

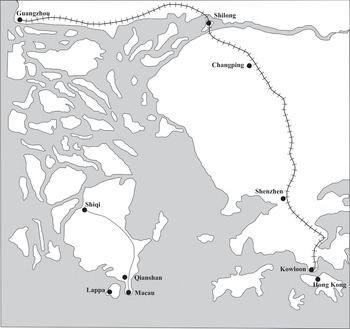

The enclave had a strategic position. Located in the Pearl River Delta, connected by land and water routes to the most important city in South China, Guangzhou (occupied in 1938), it bordered a county, Zhongshan, that was not firmly occupied until 1940, and was well connected to Hong Kong, which until 1941 was a crucial lifeline for Chinese resistance. Whilst the British colony’s importance for the Chinese war effort has been acknowledged by several historians, Macau has remained largely in the shadows.Footnote 2 This chapter demonstrates that the small enclave mattered locally and regionally and was also discussed in international diplomacy.

Watching from Afar: Macau and the Japanese Invasion of China before 1937

On 18 September 1931, an incident at a railway masterminded by Japanese military figures stationed in north-eastern China escalated into a full-on invasion of three provinces that became known as the Manchurian Crisis. In China today, this marks the official start of China’s War of Resistance against Japan and of the Second World War.

In response to Japanese actions, the Chinese government called on the League of Nations, of which China was a founding member, for assistance. Chinese diplomats in Geneva and all over the world conveyed the arguments against the Japanese aggression. Portugal was no exception. Minister Wang Tingzhang wrote to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Lisbon and transmitted the appeal being made ‘of the Chinese government and people’ calling on all the League’s signatory powers to examine the ‘invasion of Chinese waters by numerous Japanese ships’ along the coasts, including in Shanghai, escalating the conflict in Manchuria.Footnote 3 The immobility of the League was evident, however.

Meanwhile, in Macau, there were some open manifestations of support for the Chinese resistance, including speeches condemning Japan and fundraising for Chinese victims to be sent to General Ma Zhanshan, a major figure of the resistance in the north-east.Footnote 4 There is some evidence to suggest that Portuguese authorities took steps to curb openly anti-Japanese activities. For example, in 1931, the Macau authorities sought to prevent the Chinese Commercial Association (the local chamber of commerce) from requesting local merchants to participate in a boycott of Japanese products, as this could be damaging to the territory’s commerce.Footnote 5

The spread of hostilities to Shanghai, where Chinese and Japanese armies clashed from late January to March 1932, had more direct effects in the enclave, as well as on Portuguese residing in mainland China that, to an extent, and like other cities in China, anticipated some of the actions that took place from 1937 onwards.Footnote 6 The 1932 hostilities, which have been called ‘the Shanghai War of 1932’ and whose significance has been demonstrated by Donald Jordan, did not leave the Portuguese unscathed.Footnote 7 The Portuguese diplomats in the city prepared an evacuation of the community, even dispatching the auxiliary cruiser Gil Eanes from Macau. Portugal’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs archives hold detailed lists of their material losses and complaint letters on the damage caused to Portuguese properties.Footnote 8 A public subscription was started by Macau’s municipal council, the Loyal Senate (Leal Senado) to gather donations for relief of Portuguese in Shanghai, an early example of the public–private partnerships that were a dominant practice during the Second World War.Footnote 9

Although Portuguese officials were concerned only with their fellow nationals, Chinese who left Shanghai also sought shelter in Macau, as Guo Jingqiu’s case illustrates. Chinese refugees also generated a civil society response. In Macau, the Chinese population likewise organised subscriptions to collect relief funds to be remitted to the victims on the mainland, and refugees who had come to Macau were assisted by local charities.Footnote 10 One of those who reportedly sought refuge in Macau in 1932 was the film superstar Ruan Lingyu.Footnote 11 Unlike in 1937, however, when the 1932 hostilities in Shanghai came to an end, refugees largely left Macau soon after.

A refugee exodus would only unfold again – and with much greater intensity – from 1937 onwards, but, from 1932 to 1937, there were periodic echoes of the Sino–Japanese conflict implicating Macau. These usually took the form of alarmist rumours of Japanese demands. In March 1932, rumours that Japan was using Macau for military activities with Portuguese agreement arose in Chinese newspapers yet the Portuguese authorities denied them.Footnote 12 In 1935, a string of news articles reported on hearsay that a Japanese group wanted to build an aerodrome in Macau or, more spectacularly, that Japan had proposed to buy Macau itself. Portuguese authorities always rebuffed such hearsay, but the gossip did generate some international attention.Footnote 13

Even though there was a perception of relative appeasement of Japan by Chiang’s government in the mid-1930s, diplomatically, resistance never ceased.Footnote 14 Japanese actions in China continued to be brought to the attention of the international community, including small powers such as Portugal. When Manchukuo, a Japanese-sponsored colonial creation under the guise of a supposedly ‘independent’ state was established out of the three invaded provinces in the north-east, the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA) wrote to the Portuguese minister Armando Navarro, urging Portugal ‘not to give recognition to the unlawful organization born out of Japanese military action’.Footnote 15 Although Portugal did not show signs of recognising Manchukuo, neither was it openly supportive of China in the League of Nations where the Manchurian Crisis would eventually lead to Japan’s withdrawal from the international body.

In December 1932, after the findings of the League’s Lytton Report that confirmed Japan’s aggressive actions in the north-east and Chinese sovereignty over Manchuria, the Portuguese minister of foreign affairs instructed the country’s delegate ‘not to intervene in the discussion of any resolution project’. When a vote became inevitable, Portugal was to follow the British attitude, ‘softening as much as possible what in our vote may be disagreeable to China or to Japan’.Footnote 16 In other words, Portugal opted for a detached neutrality.

Portuguese diplomats regarded the situation in East Asia differently, but none advocated open support for China. The chargé d’affaires in Tokyo noted the worrying imperial confidence of Japanese authorities whose attitude ‘is becoming singularly similar to that of Germany in 1914’.Footnote 17 For his part, the Portuguese ambassador in London, Rui Enes Ulrich, considered ‘a grave error’ the League’s decision that Manchukuo should not be recognised. He praised Japanese imperialist plans, offering his ‘sincere sympathy for the notable work of Japanese colonisation’ and his ‘disgust for the liberal Chinese anarchy’.Footnote 18 Yet he too thought Portugal should not take any initiative to recognise Manchukuo because Macau’s existence made it imperative to ‘avoid any friction with China’. Thus, the country should simply follow whatever other states did on the matter. Chinese diplomats continued to monitor Portugal’s position vis-à-vis Manchukuo in subsequent years, but Portugal never advanced towards a formal recognition, the main reason for that arguably being because Britain never did.

An all-out war between China and Japan erupted in July 1937 when an incident near Beijing (the so-called Marco Polo Bridge Incident) was met with fierce military resistance. When a new front opened in Shanghai in August, that resistance became clear to the entire world. One of the most important attempts to bring the conflict to the attention of the international community occurred a few months later when the Conference of Brussels was convened in November, bringing together the signatory powers of the 1922 Nine-Power Treaty of Washington – Portugal amongst them.Footnote 19 A key power, however, Japan, declined the invitation. Ambassador Wellington Koo (Gu Weijun) made a powerful case for Chinese resistance:

China had never given any challenge to Japan before the deliberate opening of hostilities on China by Japan. The Chinese armed forces had never invaded a single foot of Japanese territory, nor had the Chinese air forced bombed a single Japanese town. China had not wished to make war on Japan and is fighting today determinedly and bravely only to resist the unceasing onslaught of the invading Japanese forces.Footnote 20

Koo’s appeal to foreign powers did not bring about the support the Chinese government desired, but Japan’s refusal to attend the conference confirmed its refusal to work towards a diplomatic solution that had already been apparent with its retreat from the League.

Portugal’s participation in the Conference of Brussels had more to do with projecting an image of colonial prestige than with solving the crisis in Asia. In one of his interventions, the Portuguese envoy, Augusto de Castro, who was the minister in Belgium, used a colonialist discourse that emphasised ‘the part played by Portugal in the civilization of Asia’, justifying its presence there with the country’s ‘political and territorial interests’ and ‘its position in the Far East’. Castro reaffirmed the country’s neutrality and merely committed to ‘lend its support to all useful work for conciliation’ to which the conference may lead ‘within the limits and spirit of its neutrality’.Footnote 21 The Portuguese chargé d’affaires in Tokyo noted that the local press was conveying the impression that Portugal was sympathetic to Japanese actions in China and its position in the Brussels conference reflected that.Footnote 22 However, in Castro’s correspondence to Salazar – who combined his post of president of the council of ministers (prime minister) with that of minister of foreign affairs – it was clear that the main preoccupation of the Portuguese diplomat was to act in accordance with the British position and maintain close relations with the United Kingdom despite existing tensions relating to the Spanish Civil War.Footnote 23 As will be demonstrated in Chapter 2, the Portuguese authorities’ policy to follow the UK position on the Sino–Japanese conflict was shaken in the following years, when Macau came into direct contact with the realities of a continuous state of war in South China. As Britain moved closer to an alliance with China, Portugal’s position became more ambiguous, even though Macau gained a new importance for the Chinese resistance.

Macau and Chinese Resistance

Communication between the Chinese Nationalist government resisting the Japanese invasion and the Portuguese authorities in Lisbon and Macau was made through diplomatic channels, personal intermediaries and contacts between provincial and county authorities and the Macau administration. These links had varying degrees of efficiency, but they were constant during the war.

Sino–Portuguese diplomatic relations suffered a period of crisis after 1938. Although China’s diplomatic representation in Portugal was marked by stability, such was not the case with the Portuguese diplomatic presence in China. The Chinese minister to Portugal throughout the period covered in this chapter was Li Jinlun, who served in Lisbon for a record period, from 1934 to 1943 (see Figure 1.1).Footnote 24 When the war erupted, Portugal’s highest-ranking diplomat to China was Minister Plenipotentiary Armando Navarro, based at the Portuguese legation in Beijing since 1930. As the Portuguese minister to Tokyo who had worked in Beijing in the 1920s noted, ‘Macau justified the existence of the legation’, since Portuguese trade and other relations with China were practically nil.Footnote 25 An extensive Portuguese community, mostly comprising Eurasian families with ancestral links to Macau, lived in some treaty ports where Portuguese consuls and/or vice consuls were either posted from Portugal (namely to Shanghai and Guangzhou) or requested to look after Portuguese interests locally. At the suggestion of Li Jinlun, the Portuguese Ministry of Foreign Affairs ordered Navarro to move from Beijing to Shanghai in October 1937 to better communicate with the government in Nanjing.Footnote 26 He died in February the following year, however, depriving Portugal of an experienced diplomat in China.Footnote 27 His successor, chosen in April, was João Maria da Silva de Lebre e Lima, who had served in London and at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Lisbon.

Figure 1.1 Li Jinlun (centre left), Chinese minister to Portugal between 1934 and 1943, after presenting his credentials at the presidential palace in Lisbon, 1934.

All was set in August 1938 for Lima to travel from the Portuguese legation in Shanghai to the Chinese wartime capital of Chongqing to present his credentials. Then suddenly his departure was suspended as the war progressed and military operations, including aerial bombing between Hong Kong and Chongqing, made travelling dangerous.Footnote 28 Lima ended up staying in Shanghai until his return to Lisbon in 1945, a permanent point of contention mentioned by the Chinese side throughout the war.Footnote 29 Although technically accredited to Chiang’s government, Portugal’s minister lived in an occupied city, mingling in the same diplomatic circles as the pro–Wang Jingwei German and Italian ambassadors. This fact is particularly illustrative of the complexities of Portuguese neutrality in China. Furthermore, all Portuguese consuls in mainland China were, from 1937–8 onwards, living in occupied cities (Shanghai, Guangzhou, Xiamen, Hankou, Harbin), and the Portuguese consul in Hong Kong was transferred elsewhere in 1939 and was not replaced by a ‘career diplomat’.Footnote 30

Diplomatic channels were thus highly uneven. With Portuguese diplomacy in China in such dire straits, Macau assumed a privileged position as a base for communication with both Japanese and Chinese of different factions, sometimes at odds with the Portuguese diplomats.Footnote 31 Chinese contacts with Macau requesting assistance from the Portuguese authorities began in the first year of the war.Footnote 32 They gained momentum as the Chinese Nationalists began to suffer serious attacks in South China from 1938.

Having attempted and failed to instigate a local coup, the Japanese started to bomb Guangzhou in February 1938. The Portuguese consul in the city witnessed the attacks and manifested sympathy for the Chinese victims in his reports to Salazar: ‘The Japanese say the targets are military but until today almost no soldier has been killed in these raids over the city. Students, women, children are the ones that have suffered in these violent and continuous daily attacks on the city. I personally went to see the result of the bombings … The spectacle is profoundly horrible and desolating.’Footnote 33

As the first city to be under a KMT government in the 1920s, Guangzhou was of great symbolic importance for the Nationalists. In a speech to Nationalist party delegates in April, Chiang Kai-shek declared that ‘Guangdong province is our revolutionary base area’ and stressed the importance of China holding Guangzhou with its key ‘sea links to the outside world’.Footnote 34 The Nationalist forces would eventually retreat from Guangzhou, but the city was defended for several months and Guangdong province was never completely occupied.

The Portuguese authorities in Macau assisted the Chinese in neighbouring areas during the Japanese bombings, providing refuge and medical care. Borders were relatively porous, which suited the needs of humanitarian assistance. In April, the Japanese bombed the Chinese Maritime Customs (CMC) post at Qianshan, near Macau, leading hundreds of people to head to the enclave.Footnote 35 The crews of the nearby boats fled in panic to Wanzai, in the eastern part of Lappa Island, with a few treated for their wounds in Macau.Footnote 36 Following a request for help from Chinese authorities, an ambulance went from Macau into Chinese-controlled territory to collect two people seriously injured after a Japanese attack.Footnote 37 After a similar request, several wounded in a bombing over Zhongshan’s capital, Shiqi, were also assisted in Macau (see Figure 1.2).Footnote 38 Chinese Minister of Foreign Affairs Wang Chonghui thanked the Portuguese minister to China in writing in December, and asked him to convey his regards to Governor Artur Tamagnini de Barbosa, the police commander and the staff who had assisted the victims in another attack on Shiqi.Footnote 39

Figure 1.2 Map of South China showing the Macau–Shiqi road and the Kowloon–Guangzhou railway.

Macau had for centuries been a source of arms supplies for China, and the war with Japan revived the practice.Footnote 40 Whilst the role of Hong Kong as a base for military supplies into unoccupied China is well known, Macau’s is less so, despite the connections between the two foreign-ruled territories.Footnote 41 For example, in May 1939, agents of the Chinese military informally approached the Hong Kong government requesting it to allow the export of war material to Macau for re-export to inland China to be used by Chinese forces in south Guangdong. This was to be done without insisting on a formal authorisation by the Macau government.Footnote 42 The Macau chief of police, Lieutenant Colonel Alberto Arez, wrote a personal letter to his Hong Kong counterpart stating that ‘we are prepared to help these people’.Footnote 43 This source, hinting that at least some amongst the Macau authorities were favourable to cooperating with the Chinese, contradicts the governor’s assurances to Lisbon that no military assistance was dispensed. However, the plan did not secure British approval.Footnote 44 The reason for the denial was that such a proposition posed ‘a grave risk of a clash with the local Japanese naval authorities’.Footnote 45 Whilst some were willing to take risks, others feared international consequences.

Sino–Portuguese contacts were also established for matters concerning Portuguese interests in the enclave. In May 1938, the governor sent Arez to speak to the provincial governor, Wu Tiecheng, via the Portuguese consulate at Guangzhou. He was to discuss the presence in Macau of Japanese elements spreading anti-Portuguese propaganda and causing problems between Portugal and China. He suggested that, should the Guangzhou authorities know who the troublemakers were and request it, the governor would be willing to hand them over unless they were long-term residents. The consul considered this offer extremely problematic but helped Arez to write a more general note that ended up being received by Diao Zuoqian, special delegate of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Guangdong and Guangxi. Equally vague in his response, Diao guaranteed that ‘Macau’s tranquillity was very important to China and to Guangzhou, given the high number of Chinese who lived there.’Footnote 46 Such was the strange coexistence of imperialism and anti-imperialism in exceptional times of war, when the neutrality of a foreign colony was quite useful to Chinese resistance. Attempts to get supplies into Macau were also made via personal channels.Footnote 47

However, cooperation was neither linear nor constant. Sometimes, Chinese actions around Macau prompted protests by the Portuguese, such as in May 1938, when several Chinese planes flew over Macau on their way to bomb Japanese positions outside of Portuguese waters, or in October, when Chinese troops patrolling a so-called neutral zone wounded a Portuguese lieutenant from the Barrier Gate (Portas do Cerco) garrison.Footnote 48 Protests were sent from the Portuguese consul in Guangzhou to the provincial authorities and assurances were given in writing or in person, by Diao Zuoqian or the secretary, Ling Shifen.

Diplomatic correspondence between Portugal and China during the war can be described as a litany of complaints and rebuttals, with the Chinese government insisting on official clarifications to any information it received on possible breaches of Portuguese neutrality in Macau. These are indicative that Chinese wartime diplomacy was attuned to a myriad of affairs and did not overlook relations with a small European power. The Chinese minister in Lisbon, Li Jinlun, went to the Portuguese Ministry of Foreign Affairs several times to get a reaction to news on events in Macau or rumours about Portugal’s stance on Japan. Similarly, the dispatches of the Portuguese minister to China to the Chinese minister of foreign affairs in Chongqing usually contained denials of such rumours. For example, in May 1938, Lima wrote to Wang Chonghui, via the Portuguese consulate in Hong Kong, to deny the news that Portugal would recognise Manchukuo. In his rebuttal, he admitted the de facto existence of parallel diplomacy between Macau and Japanese forces:

It is possible that between the Government of Macao and the Japanese authorities there exists some kind of understanding or local agreement in connection with shipping facilities. However, I have the honour and pleasure to assure Your Excellency that the news regarding the existence, for the above purposes, of any treaty or negotiations between the Portuguese and the Japanese Governments have no foundation whatsoever.Footnote 49

The Japanese occupation of Guangzhou added a layer of distance between the Portuguese diplomats and the Chinese central government. The city fell in October 1938 with little military resistance, almost at the same time as the Nationalists lost the temporary wartime capital of Wuhan. The city’s occupation may be regarded as the transition between a first phase of the Second Sino–Japanese War and a ‘second, defensive stage’ that ensued.Footnote 50

As the Nationalists lost ground in South China, Macau made its riskiest move in shadow diplomacy. In February 1939, the Macau police commander, Captain Carlos de Sousa Gorgulho, went to Tokyo, where he met a number of Japanese officials – an event that will be discussed further in Chapter 2.Footnote 51 The visit caused a stir in Sino–Portuguese relations. In Paris, Ambassador Wellington Koo lamented the news he had heard of an agreement between the government of Macau and Japan that included the recognition of Manchukuo and the free use of the Macau port. Koo interpreted the affair as part of Japan’s efforts to ‘poach the lesser signatories of the Washington Treaty’.Footnote 52 The minister in Lisbon, Li Jinlun, came to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to enquire if the news was true. He was told it was not.Footnote 53 Li later delivered a note on the matter, noting that there was information that ‘some members of the Macau government favour the pro-Japanese policy’ advocated by Gorgulho.Footnote 54 A document from the Chinese Military Affairs Commission informing the Ministry of Foreign Affairs on Gorgulho’s trip and the proposals he had discussed shows how these caused high-level concern. The Nationalists feared Japan was attempting to use Macau as a base and to influence Portugal to join the Anti-Comintern Pact, which was not far-fetched, given Salazar’s anti-communism.Footnote 55 Shortly after, Li Jinlun presented the ministry in Lisbon with this new set of allegations of Portuguese collaboration with Japan that he wished to see clarified.Footnote 56 Those were denied, but increasing Japanese pressure in the vicinity of Macau was a reality, one that Chinese officials were well aware of.

The ‘Portuguese’ Ships

An illustrative way in which neutrality shaped Sino–Portuguese relations at a non-state level – but that often spilled out into consular démarches – was the registration of Chinese ships under Portuguese nationality, several of which were used for smuggling materiel to both Chiang’s China and Japanese troops. As a Portuguese consul wrote at the time, the ‘Portuguese merchant fleet’ in China was ‘the illegitimate daughter of the Sino–Japanese conflict’.Footnote 57 Correspondence about detained ships, many of which were involved in the lucrative, albeit risky, transport of weapons, ammunitions or goods destined to both of the belligerents, is one of the sources that attest to the flexibility of Portuguese neutrality in the war. Japanese representatives accused the Macau authorities of protecting Chinese boats that attacked Japanese warships;Footnote 58 sometimes it was the arrest of Chinese and their boats that motivated protests by China.Footnote 59

Japan had informed foreign powers that the transfer of Chinese ships to foreign ownership since August 1937 would be recognised only with bona fide proof of the transfer. A consequence of this was the registration of Chinese boats under foreign flags, of which Portugal’s was an easy choice, most likely because the limited financial capacity of the Portuguese in China made them more prone to agree to such a scheme. Throughout 1937 and 1938, Japanese navy patrols often stopped and searched ‘Portuguese’ merchant ships such as the Wing Wah and the Anjou, Chinese junks with permits from the Macau Harbour Authority and Chinese junks travelling between Hong Kong and Macau. Some had their cargo seized whilst others were attacked, the crew left to die.Footnote 60 A public accusation that Chinese junks and speedboats were using Portuguese territorial waters in South China to launch raids on Japanese warships was made by a Japanese navy spokesman in Shanghai in April 1938, which was amply reported both in Shanghai and in Hong Kong.Footnote 61 Although the Macau government and the Chinese military authorities denied this, these cases illustrate the ease with which the ships could be deployed for pro-resistance purposes.Footnote 62 In July 1938, the minister of colonies, Francisco José Vieira Machado, wrote to the governor of Macau that it was ‘not convenient to facilitate the matriculation of Chinese junks as Portuguese boats [as] it will be [a] source [of] conflicts without any advantage’.Footnote 63 Barbosa replied that such measures would only last during the conflict and blamed the trouble on ‘the abuse of Chinese boats’ using Portuguese flags, as if Portuguese officials had not permitted such use of the flags.Footnote 64 However, sometimes that was not the only flag they used: one of the vessels the Japanese detained in 1940, the Fu An (Fuk On in Cantonese), ‘flew the Portuguese flag’ whilst having ‘a painted flag of the Chiang Kai Shek regime on her stern’, evidence of a rushed transfer of ownership or of its true allegiance.Footnote 65 However, not all the ships were stopped by the Japanese side. In 1940, the Chinese authorities in Fujian detained the boats Tito and Santa Rosa, including the Portuguese captain and crew, accused of collaborating with the enemy.Footnote 66 Such were the dangers and opportunities of neutrality: a Portuguese flag could facilitate shipping but was not a stable guarantee against attacks by one of the belligerents.

The registration of former Chinese ships as Portuguese was an open secret and was employed as a strategy for mutual benefit, given that Macau needed supplies from inland China and the Portuguese needed Chinese capital for the ships and could also profit from their trade.Footnote 67 Even Portuguese representatives were involved: one prominent case involved the Luso, a ship bought by the vice consul in Shanghai, Antonio Augusto Alves Lico. Attempts to tackle the situation were half-hearted. In the summer of 1939, instructions were given to Portuguese consulates in China and to the Macau Harbour Authority not to nationalise Chinese or Japanese ships as Portuguese. Temporary boat passports were to be replaced for definite ones, and in cases where there were legal impediments, solutions were to be found to guarantee that nothing really changed so as not to cause trouble to the Portuguese involved in the traffic. In any case, by 1941, most of the ‘Portuguese’ ships had been apprehended by Japanese or Chinese authorities. Portuguese consuls at Shanghai and Guangzhou repeatedly pleaded with them, but release of the boats and sometimes their crews was a lengthy and not always successful process. The Portuguese consul in Guangzhou concluded: ‘The “Portuguese fleet” is not respected by any of the two contenders, because both know the way in which it was acquired.’Footnote 68 The registration of Chinese ships under foreign flags mirrored the registration of businesses in the neutral International Settlement and French Concession in Shanghai.Footnote 69 These were strategies for survival in which nationalism and transnational connections overlapped.

The Portuguese ships were one channel amongst others and the important role Macau played in smuggling weapons and other supplies into Free China is attested by contemporary sources of different provenances, including a report by the manager of the Banco Nacional Ultramarino (BNU) and an American document noting that ‘a considerable amount of railway material’ and small quantities of munitions entered China via Macau.Footnote 70 Some of these were likely to have been deployed nearby, as Macau’s environs became a frontline of hostilities.

Defending Zhongshan

The Japanese Expeditionary Forces in South China had held positions encircling Zhongshan county since the late 1930s but had not moved into the capital, Shiqi, until the end of the decade. They tried to convince local elites to settle for peace and neighbouring Macau was one of the chosen meeting places. According to a British account, based on a pro-resistance source, at least five meetings took place in Macau between Japanese officers and representatives of the Zhongshan authorities between December 1938 and February 1939 to guarantee a smooth occupation without violence. The Japanese side promised the return of foreign concessions and colonies and the abolition of extraterritoriality, but ‘the Chinese representatives retorted that it was impossible to reconcile the Japanese protestations of friendliness, with the indiscriminate attacks on the local civilian populace as exemplified in the burning of junks, raping of women … or the shooting down of the C.N.A.C. [China National Aviation Corporation] plane “Kweilin”’.Footnote 71 Appealing to anti-imperialist solidary meant little when it was accompanied by imperialist aggression.

Armed resistance to the Japanese was made not by regular troops but by militia,Footnote 72 which, a newspaper claimed, ‘imported arms and ammunitions through third parties at the border’ – that is, via Macau (see Figure 1.3).Footnote 73 This may explain why military historians have largely overlooked the region.Footnote 74 Fighting around Shiqi occurred from the spring of 1939 and intensified during the summer and fall when the county was heavily bombed, disrupting food production and supplies, including of manufactured goods, between Hong Kong and Macau and the interior of China. Concerning reports reached diaspora communities as far away as San Francisco.Footnote 75 As Macri observed: ‘The Chinese defended the birthplace of Sun Yat Sen with great determination, and although the fight for Shekki [Shiqi] was small in scale compared with other significant battles, its political impact helped prolong the war.’Footnote 76 Three assaults on the city failed in September, but on 8 October, Japanese forces occupied it. However, they had to withdraw after two days and the local magistrate, General Zhang Huichang, returned.Footnote 77 Like many other Nationalist officials, Zhang’s life story was marked by global connections. He grew up in the United States, graduated from a flight school in New York and became an American citizen. He returned to China in 1917, was Sun Yat-sen’s aide-de-camp and the leader of his first squadron of aviation corps, later bureau chief of the Canton Aviation Bureau and director of the Nationalist government Aviation Office in Nanjing. An aviation celebrity, he fell from grace after joining the Fujian People’s Government, destroyed by Chiang Kai-shek in 1933. He served as a diplomat in Cuba before returning to serve as the head of Zhongshan county. By 1939, anti-Japanese resistance put him again on Chiang’s side.Footnote 78

Figure 1.3 A Chinese woman fighting for the resistance in Zhongshan, 1939. Sueddeutsche Zeitung Photo / Alamy

Worried that combat might spread to what was considered a ‘neutral zone’ between Macau and Qianshan, or that Chinese troops might seek refuge in the enclave, Governor Barbosa sought to reinforce Portuguese defences near the border. He was also involved in contacting the local authorities via intermediaries to convince them to avoid a bloodbath by giving up what he considered a ‘pointless opposition’.Footnote 79 Chinese resistance in and around Macau was tolerated, but Barbosa would prefer that it did not pose too many problems for the Portuguese in Macau. Others were more understanding, however. Anti-Japanese activities in Macau were a consequence of the brutal invasion, and the Portuguese consul in Guangzhou knew it would be ‘almost impossible to completely prevent them in a land where around 200,000 Chinese live who cordially hate the invader and victorious oppressor’.Footnote 80

In early March 1940, Japanese naval units advanced again into Shiqi following the same route as the previous year. An army of around 25,000 men under Wu Fei, who had been the county leader since 1939, resisted the invasion but was overpowered. Japanese naval and land forces blockaded coastal areas while naval air units bombed the retreating Chinese. The city was taken in three days.Footnote 81 From Chongqing, a Chinese military spokesman dismissed the operation as of ‘no military significance’ and probably carried out ‘for certain political reasons connected with the Japanese attempt at an early establishment of a new regime in China’.Footnote 82 News in pro-Japan Chinese newspapers in Guangzhou claimed the pro-Chiang guerrillas, who had provoked the Japanese advance on Shiqi, had been operating from and were aided by Macau. The governor of Macau believed Wu Fei had collaborated with the Japanese. The Portuguese consul in Guangzhou disagreed, confirming the rumours that he was acting under orders of the Nationalist government, fooling both the Japanese and Barbosa.Footnote 83 These contradictory views demonstrate how volatile the South China front was, with those engaged in resistance and collaboration not always unequivocally differentiated.

The Kuomintang in Macau

The presence of neutral foreign colonies and concessions bordering Guangdong province was of great importance to harness support for Chinese resistance.Footnote 84 At an early stage, Hong Kong and Macau were regarded as one entity and KMT cadres usually operated in both, often being based in Hong Kong, which was deemed more important.Footnote 85 As the Nationalists suffered a series of defeats and Japanese-occupied areas expanded, the importance of neutral territories grew and there was a significant rise in the number of party members in Hong Kong, Kowloon and Macau.Footnote 86 Wu Tiecheng, the former mayor of Shanghai and governor of Guangdong province, headed the Hong Kong–Macau branch, which had been reorganised and became independent from the tutelage of the Guangzhou one it had formerly belonged to.Footnote 87 In 1939, Wu entrusted responsibility for the Macau section to Zhou Yongneng, who earlier in his career had played an important role in establishing a KMT branch in Cuba. Wu also asked the KMT Central Committee to make Zhou the head of the Guangdong Office of Overseas Chinese Affairs.Footnote 88 A mass rally supporting the resistance was held on Lappa island in May 1939, with the participation of Macau patriotic associations.Footnote 89

Chinese resistance activities had to deal with increasing interference from the Portuguese authorities. In September 1939, they sent the police to search offices, houses and schools of Chinese representatives in Macau. Chinese sources state that, after the Japanese consul had protested to the governor against the Chinese government in Chongqing having many people engaged in anti-Japanese activities in the enclave, and requested the Portuguese stop them, Barbosa had agreed to send the Macau police to search for propaganda materials. Zhou’s house and the Chong Tak [Zhongde] Middle School were searched, materials were confiscated and some people were arrested.Footnote 90 The Portuguese police had also asked for the money collected from donations for refugee relief.Footnote 91 These actions seem to indicate that Portugal was breaching its neutral status and favouring Japan. The Chinese legation in Lisbon was instructed to protest to the Portuguese government and urge it to enquire about the matter with the Macau authorities.

Further information that the Macau police had raided offices, schools and residences searching for anti-Japanese materials reached the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs in October. This was based on a Chinese intelligence report (qingbao) informing on Portuguese–Japanese collaboration that had included the acceptance of payments from the Japanese in exchange for help to arrest Chinese officials and spies engaged in anti-Japanese activities in Macau.Footnote 92 Li Jinlun delivered a note to the Portuguese Ministry of Foreign Affairs stating that the Chinese government had been informed of a decision to crack down on Chinese relief institutions in Macau, including the seizure of more than 10,000 Chinese dollars that the Commercial Association had collected for refugees. They had been ordered to dissolve because if the Japanese captured Zhongshan and demanded a list of Chinese involved in anti-Japanese activities, the Macau government could not be responsible for their safety.Footnote 93

In a follow-up meeting at the ministry, Li insisted on clarifying the rumours, particularly the threat of handing Chinese refugees in the enclave over to the Japanese military authorities if they advanced close to Macau. He wanted guarantees from the Portuguese that the Macau authorities would not do such a thing.Footnote 94 Barbosa reported to Lisbon that all of the rumours were false. Chinese merchants who raised funds for refugees were just asked to present their balance sheets to prove funds were not being sent to the resistance as the Japanese suspected.Footnote 95 This was a somewhat impossible request given the entanglement of relief and resistance in South China. Once again, however, the Chinese central government was quick to use diplomatic channels to hold the Portuguese accountable for what was happening in Macau.

Despite the Japanese military forces citing KMT activities in Macau to pressure the Portuguese, these continued to take place. A report from Japan’s national news agency, Dōmei, claimed that a KMT meeting had been held in Macau in January 1940, where Chiang ‘was praised’ and Wang Jingwei ‘was criticized’.Footnote 96 The governor denied this, but Zhou Yongneng later confirmed that the meeting had taken place on Lappa.Footnote 97 This is also attested by a letter from Jack Braga, assuring the report was erroneous but confirming that KMT meetings did occasionally take place in Wanzai on the eastern part of Lappa. Braga hailed from an important Hong Kong Portuguese family and lived in Macau from the late 1920s to 1946. He was a Reuters and Associated Press correspondent and a teacher and, as detailed in Chapter 5, also worked for British, Chinese and possibly American intelligence during the war. He stated that the majority of those attending the meeting were Macau residents and the branch was known as the Macau Kuomintang. Braga believed the branch was not engaged in anti-Japanese propaganda ‘but concentrate their attention on getting subscriptions for Chinese war charities, and keep an eye on any of their own nationals who happen to be pro-Japanese’.Footnote 98 The line between relief and resistance was often a thin one.

Crackdown on KMT activities grew in the later stages of Barbosa’s governorship, and from 1940 onwards they were mostly forced underground.Footnote 99 In June 1940, Chiang Kai-shek was informed that the Macau governor had reached a tacit agreement with Japanese forces. He would suppress the activities of Chinese patriotic groups and in exchange Japan would prevent a blockade of Macau. Chiang lamented in his diary that Macau was now completely under Japanese control.Footnote 100 Zhou Yongneng recalled in his memoirs how his presence in Macau was cut short when he was arrested. When his identity was revealed in a newspaper, the governor of Macau ceded to Japanese pressure and sent the police to arrest him. Wu Tiecheng, with the help of some influential Chinese personalities from Macau, managed to prevent Zhou’s extradition to the Japanese. Instead, he was simply expelled from Macau and forbidden to exercise activities there.Footnote 101 He went to Hong Kong where he remained until the death of Governor Barbosa and his replacement by Gabriel Maurício Teixeira, whom Zhou described as anti-German and not sympathetic towards the Japanese. Zhou managed to resume work in Macau through Catholic networks and he cultivated good relations with the new governor and others in the administration.Footnote 102 Although he lived in Kowloon, Zhou often stayed in Macau. He was there for a party meeting when the invasion of Hong Kong began and he remained stranded in Macau for the following weeks. He then fled to Chongqing after learning that collaborators were planning to kill him.Footnote 103 Zhou’s case is illustrative of the multiple local and transnational links that sustained Chinese resistance in South China.

Official and shadow diplomacy were occasionally intertwined. At the end of 1940 and in April 1941, Li Shizhong, a former chargé d’affaires in Portugal, came to visit the new Macau governor. He identified himself as an envoy of Chiang Kai-shek, who wanted him to be his delegate in the enclave.Footnote 104 Teixeira replied he could only consider him privately – as an official appointment had to be granted by Lisbon – but he did not dismiss him. Indeed, assistance could be and was requested through these semi-informal channels. When the governor was asked to allow the supplying of gasoline to Free China, he told Li that Portugal’s ‘honest [and] loyal neutrality policy could not allow’ an approval. When he suggested that perhaps contraband could be permitted, Teixeira’s answer was ambiguous: ‘when smugglers were caught, they would suffer the legal penalties’.Footnote 105 This implied that they would be free to continue their activities if they kept a low profile.

As these contacts attest, Chiang Kai-shek had not given up on Macau as an entrepôt for Chinese war supplies. In February 1941, the governor informed Lisbon that Chiang had sent a special delegate, Wang Zhengting, to Hong Kong and Macau. Wang was a former minister of foreign affairs and had been China’s ambassador to the United States between 1936 and 1938. He had not been able to visit Macau, arguably because Japanese were searching boats travelling between the two colonies. Since Wang had asked to exchange views with the Macau government, the governor sent Pedro José Lobo to Hong Kong to meet him. Lobo was one of the most powerful figures in Macau, remaining a key intermediary figure throughout the war years and afterwards. He was instructed to listen to whatever Wang had to say but only to talk about assistance to refugees: ‘[W]ithin [its] impartial neutrality, the Macau government will continue to assist Chinese refugees not only because [of] the never-interrupted friendship between our two countries but also by compliance with the Christian spirit [which is the] base of the New State [Estado Novo authoritarian regime] doctrine.’Footnote 106

Mentioning Christianity may have been an attempt to stress a common ground given Chiang’s Christian faith and the Christian influence over his New Life Movement implemented, like the New State in Portugal, in the 1930s.Footnote 107 The reference to the Chinese refugees in Macau – by then already numbering in the tens of thousands – attests to the links between humanitarian assistance and political expediency in the enclave, an issue that will be analysed in Chapter 3. During his meeting with Lobo, Wang transmitted official thanks from Chiang Kai-shek for Portugal’s ‘correctness [and] friendship with China and assistance [to] refugees’, having sent a jade stone ring to the governor as a ‘symbol of friendship’.

Before leaving for Chongqing, Wang said he would return within a few months and would visit Macau unless there was a risk of detention by Japanese forces. Teixeira later notified Lisbon that he had information of ‘secret negotiations’ taking place in Hong Kong between delegates of Chiang Kai-shek and Wang Jingwei. Wang, he said, had been showing resistance towards the Japanese and refused to nominate a pro-Japanese candidate to govern Shiqi.Footnote 108 Japanese agents were working in Guangdong distributing donations for propaganda purposes and advocating peace. However, according to the governor, Chiang remained the ‘main figure’. He told his superior that ‘if Chiang does not make peace [,] even if the Japanese keep Wang Jingwei [,] his authority will be more and more fictitious’. The governor then clearly stated his position in the matter. ‘[O]ur policy is not altered: honest neutrality but, within it, friendship with Chiang.’Footnote 109 This was a more open expression of cooperation with Chinese resistance than the actions of his predecessor.

Nationalist resistance’s interactions with Macau were part of a wider picture of making creative uses of neutral foreign-ruled territories in China, to which Shanghai’s foreign concessions and Hong Kong were key. Chiang’s men were not the only ones operating in these, however.

Communist Mobilisation

Communist guerrillas had been recruited in Macau since the early stages of the war. Both the KMT and the CCP were involved in cultural activities taking place in Macau to mobilise support for the war effort, including sonic and visual propaganda such as the 1938 documentary series Kangzhan teji (War of Resistance Special) shown at the Apollo Theatre in Macau.Footnote 110

The origins of the CCP in Macau have, so far, lacked scholarly attention, but it is known that the party was present in Macau before 1937. Chen Shaoling, a CCP member from Taishan who had fled the KMT to Malaya in 1927, came to the enclave in 1935, where he opened a ‘progressive’ bookshop and sought to mobilise teachers, students and workers.Footnote 111 The Second United Front with the Nationalists during the war provided a golden opportunity for the CCP to expand their activities in places such as Macau and Chen played an important role in mobilisation efforts within and beyond Macau.

One of the city’s newly founded charities, the Four Circles Disaster Relief Association (Sijie jiuzaihui), was linked to Communist resistance. The circles were academic, musical, theatrical and sporting. It included more than fifty smaller associations (schools, sports teams, media, musical and theatre groups, etc.) and more than 100 people. Founded in August 1937, it organised a variety of fundraising activities (such as entertainment events, sports competitions and collection of donations on the street). These groups’ work included propaganda activities to mobilise the rural communities and provision of medical treatment, for example, to victims of Japanese bombings, as well as actual fighting.Footnote 112 The association provided training to youth teams dispatched to engage in popular mobilisation and guerrilla fighting in inland China. The Macau Chinese Youth Countryside Service Group (Lü Ao Zhongguo qingnian xiangcun fuwutuan) was the first Chinese service group to send members to the interior.Footnote 113 Several of its young members lost their lives in the conflict.Footnote 114

After the fall of Guangzhou, the Four Circles Disaster Relief Association Return to the County Service Group (Sijie jiuzaihui huiguo fuwutuan) was set up, with Liao Jintao as leader.Footnote 115 Liao, an underground CCP member, was a clerk in a motor company in Macau and was responsible for the propaganda department of the Four Circles Association, travelling to Guangzhou and other places near Macau and mobilising people to support the resistance. The Nationalists arrested him in 1941, and he ended up dying in jail at just twenty-seven.Footnote 116

That same year, General Ye Ting, commander of the New Fourth Army, is mentioned as having come to reside in the enclave. Ye had been arrested and tried in the New Fourth Army Incident that had fatally damaged the CCP–KMT United Front. He was reportedly imprisoned until the end of the war.Footnote 117 However, according to a telegram from the governor of Macau, after being arrested by the Nationalists, Ye returned to Macau, where he had sought refuge in 1935.Footnote 118 The governor notified Lisbon that he would summon Ye to tell him that ‘he would let him stay in Macau as long as he observed absolute correctness [in his behaviour] but at the minimum communist activity he would be arrested and deported’.Footnote 119 It is unclear if Ye’s return to Macau did indeed take place and, if so, how long it lasted and what its purpose was.

As will be detailed later, the CCP presence in Macau became stronger in the 1940s when some future key figures started to operate in the Portuguese enclave. Chinese historians now credit the party with the bulk of anti-Japanese resistance activities in and around Macau.Footnote 120

Macau and Chinese Collaborators

Neutral territories were prime sites for the coexistence and interaction of opposing forces during the Second World War. Macau was important both for those supporting resistance against Japan and for those attempting to settle for peace, most notably Wang Jingwei and his circle. As will become clear in this section and in Chapter 4, the enclave was a peculiar participant observer in the rise and fall of Wang’s RNG.

Unable to convince Chiang Kai-shek to accept surrender, the Japanese turned their attention to Wang Jingwei, an important KMT figure who regarded Chiang as a rival who had usurped his ‘rightful place as leader of the National Revolution’.Footnote 121 Together with a group of close associates, Wang left Chongqing in December 1938, bound for Hanoi in French Indochina, and Hong Kong. In these then-neutral colonial territories, Wang and his circle began to negotiate with Japan, responding to covert overtures for peace that had been happening for some time and would continue for the rest of the conflict. After leaving Chongqing, Wang began to contact a number of figures in areas where he and his wife, Chen Bijun, were well connected. Chen, who had been born in British-ruled Penang, played a key role in Wang’s shift towards Japan and actively lobbied for his ‘Peace Movement’. She led one of the two main factions of Wang’s supporters, the furen pai or ‘Madame (Wang) Faction’, that came to dominate occupied Guangdong’s economy and politics.Footnote 122

One of Chen Bijun’s colonial stopovers was Macau. In January, the governor reported to Lisbon that Chen had ‘come to reside in Macau’, believing it to be a safe location.Footnote 123 Guangdong province had long been a key area of support for Wang, a native Cantonese who had been a close associate of Sun Yat-sen. It is not surprising that the Wangs’ first efforts to develop an alternative government to that of Chiang’s involved meetings with other Cantonese elites, facilitated by the official neutrality of the foreign-ruled territories in South China. These territories also offered opportunities to reach out to European authorities.

It was via Macau that Wang Jingwei arrived at Guangzhou in July, on the Japanese ship Shirogane Maru.Footnote 124 He broadcast a key speech in the provincial capital, calling for peace with Japan and condemning Chiang and guerrilla actions in Guangdong, and the suffering they inflicted on the local population.Footnote 125 His pleas were not unanimously well received and his attempts to convince key KMT military figures, such as General Zhang Fakui, to defect failed.

In Hong Kong, Wang’s supporters faced fierce opposition from pro-resistance circles and were met with a cold, if not downright hostile, position from the British colonial authorities, well exemplified by the difficulties faced by the Hua nan ribao (South China Daily News), a Hong Kong–based newspaper that was an important propaganda mouthpiece for Wang.Footnote 126 Despite this, his moves to gain prominence in occupied South China had some traction. Although Wang ended up relocating to Shanghai, a pro-Wang Guangdong Political Affairs Committee was established later in 1939. By then, Cantonese collaborators were divided into factions, one of them Chen Bijun’s, fighting for power. In a bid against Chen’s faction, Peng Dongyuan, one of the collaborators the Japanese had put in charge of Guangzhou, made himself mayor of the new Guangzhou Municipal Administrative Office. Eventually, Chen’s faction – with the support of the head of the Japanese army special services in Shanghai, Kagesa Sasaki – succeeded in dominating Guangdong province, where a new provincial government was established in May 1940.Footnote 127 Several of the provincial government committee members were part of Chen Bijun’s faction, and she was appointed to the position of Guangdong political director that granted her extensive powers of supervision over government affairs in South China.Footnote 128

If Wang Jingwei used Macau as a stopover for his démarches in South China, so did Chiang Kai-shek’s envoys, who were determined to make Wang’s efforts collapse. Wang’s rival government had been officially inaugurated on 30 March 1940 without formal recognition by Japan, which ‘still hoped for a peace settlement with the real power in China, the National Government’.Footnote 129 In June, high-level contacts that had begun in Hong Kong between Nationalist agents and Japanese military figures were resumed in Macau. The talks revolved around ‘Chinese recognition of Manchuria and Japanese stationing of troops in North China’ and went as far as the signing of a memorandum agreeing that Chiang would meet Itagaki Seishirō, chief of staff of the China Expeditionary Army, in Chongqing in August, but then Chiang abruptly cancelled them.Footnote 130

In early November, a more informal meeting took place in Macau between Du Shishan, one of the Nationalists’ ‘unofficial representatives’, and Toyama Shuzo, son of a friend of Sun Yat-sen, who warned of the imminent recognition of the Wang Jingwei regime. This was one of the Nationalists’ last efforts to obstruct that recognition.Footnote 131 However, they did not stop trying to discredit the RNG and even unlikely actors were used to ensure this. For example, news from Chongqing that the Chinese apostolic vicar of Nanjing, Yu Bin, called for opposing the Wang government, was published in the main Macau daily.Footnote 132 The impact of such reports on a considerable local Chinese Catholic population is unknown but is easily imaginable, particularly given the Japanese bombing of Catholic missions in the province that will be addressed in the following chapter.

Meanwhile, the RNG authorities in Guangdong found Macau useful for other purposes. In May 1940, a new Zhongshan county magistrate contacted the Macau authorities with commercial proposals. He was organising an export regime to neighbouring territories and promised to make Macau’s harbour a distribution hub, as well as to replace the Lappa island garrison with one more in line with Portuguese interests. In exchange, he wished to obtain 20,000 patacas to cover the district’s organisational expenses.Footnote 133 In a top-secret telegram to Lisbon, Governor Barbosa expressed his approval, fearing economic reprisals if he did not comply. Everything would be taken care of confidentially, involving only the governor and two other associates, one of them Lobo. With the bluntly racist language sometimes found in official correspondence, he exonerated himself of any responsibility, noting that ‘all Chinamen are venal’, it was not such a high amount, ‘and the general has volunteered to issue a receipt which is a valuable document for us and places him, in a way, in our dependency’. Ever mindful of colonial comparisons, he added that ‘it is like this that other foreign countries have managed their tranquillity and the maintenance of their interests in the Far East’.Footnote 134 In other words, since everybody was collaborating, it was not a problem.

The minister of colonies was not particularly enthusiastic at first. Such things ‘are perhaps very common [in the] East but they contradict our principles [and] shock our sensibility’, he telegraphed. The whole affair was likely to lead to more demands and would look very much like blackmail. However, if the Lappa settlement meant a Portuguese reoccupation of Lappa, he added, using ‘these means would not be so repugnant’. The minister approved the operation, hoping for the ‘moral sacrifice’ to be justified by ‘advantageous results’.Footnote 135 For the governor, compromise was imperative because the ‘maintenance [of] gambling, opium and commerce profits depend[ed] [on the] sympathy [of the] high authority [of the] Zhongshan district’.

Morality was a strange thing indeed, for its sacrifice was, after all, to buy Macau’s financial solvency through activities that elsewhere attracted moral condemnation. The money would be considered a loan and the replacement of the Lappa garrison by one less hostile to Portugal would allow the Macau authorities to scale down maritime security measures. In sum, collaboration with the collaborators would be ‘very useful at least economically’, especially given the unrelenting Japanese pressure.Footnote 136 Such desire for stability soon gave way to more demands.

Authorities in Zhongshan tried to control access to Macau in different ways. These interactions served multiple and intersecting purposes, from personal profit to protection of power or expansion of influence. In November, a tax was imposed on everyone who went to Macau. The new governor, Gabriel Teixeira, informed Lisbon he would try to negotiate a reduction. An opportunity came up when, a few months later, the newly appointed magistrate of Zhongshan remained in Macau, hiding from the supporters of his predecessor, ‘who wanted to assassinate him’, and waiting for the Japanese to ‘clean up Zhongshan’.Footnote 137

The case highlights how different collaborationist factions in the south had differing degrees of closeness with the Japanese military forces. The Macau governor granted him protection, including authorisation for gun licences for his two bodyguards.Footnote 138 In May, the magistrate came to visit Teixeira with customary ‘wishes of collaboration’ (desejos [de] colaboração). Confirming those to be his wishes as well, the governor suggested that a practical way of doing so would be to lower the taxes over people and goods travelling between Macau and Zhongshan, as well as to facilitate the return of refugees in Macau. The magistrate requested to station a representative to deal with Macau–Zhongshan issues, a refugee from Zhongshan who had been living in Macau for four years. He was a graduate of an American university and a ‘friend’ of the Portuguese. The governor accepted.Footnote 139 Personal links, however, were a volatile insurance in a region ravaged by factions and war. In mid-June, the magistrate was assassinated in Macau, shot dead by three Chinese who escaped.Footnote 140 Even though the governor assured Lisbon that he had provided everything for the man’s safety, the incident was a pretext for the RNG to protest as a state would.

Complaints and demands were opportunities for the RNG to affirm its claims as the legitimate Chinese government. A protest about the magistrate’s assassination came via the commissioner for foreign affairs of the Guangdong provincial government, Zhou Bingsan, accompanied by a Japanese adviser. The demands were harsh: a written apology by the Macau government; immediate handing over of the criminals; punishment of the responsible Macau government staff; financial compensation for the family of the deceased; and guarantees that similar incidents would never again take place. Teixeira refused to accept, claiming he had granted all requests for the deceased’s protection and had kept good relations with him. The Japanese sided with the governor, and their agent told Teixeira that their investigations in Shiqi pointed towards the assassination having been requested by the Nanjing government itself.Footnote 141 This case highlights the divisions amongst collaborators and how internal decisions influenced informal external relations.

As in Shanghai, where – as Frederick Wakeman demonstrated – political terrorism became an everyday reality between 1937 and 1941, political assassinations continued with frequency in South China, sometimes perpetrated in Macau.Footnote 142 One of the victims was the Guangzhou police sub-chief.Footnote 143 He was the fifth man working for the RNG provincial government killed in Macau between June 1940 and September 1941.Footnote 144 A new protest ensued. The Guangzhou authorities wanted to send their staff in order to, they claimed, cooperate with the Portuguese authorities in ‘exterminating dangerous Chongqing elements in Macau’. Licences for carrying guns would be issued to them and their bodyguards. After some negotiating, the governor granted 20 licences – much fewer than the 150 demanded – and tried to get the Japanese representatives to support him. Then he called a representative of Chiang’s government in Hong Kong, urging him of the ‘imperative need to impose on his supporters respect [for] Macau’s hospitality [and] neutrality’.Footnote 145 The agent denied Chongqing’s involvement in the assassinations. The fact that the governor believed it had been the Nationalists is not surprising as their underground actions against collaborators were common during the war.Footnote 146 This episode reveals that, although pressured by the RNG authorities, the Portuguese authorities in Macau continued to maintain contact with Chiang’s men.

The Nationalists were paying close attention to what was happening in Macau and regularly sent representatives to ensure the Portuguese authorities had not changed sides. In early May 1941, Ling Shifen visited the governor. He wanted to ascertain whether the Macau government had recognised Wang’s, and if the Japanese had espionage services in the enclave and were pressuring Chinese schools and associations to support Wang.

Teixeira confirmed not only that the Macau government had not recognised the RNG, but also that such a decision rested with the metropolitan government. On the other issues, he had no knowledge of Japanese spying in Macau and did not think it necessary given that Japan occupied all the neighbouring territories. As for co-opting the Macau Chinese, he only knew that Colonel Okubo Hiroshi, a Japanese liaison officer, had invited the president of the Commercial Association to support Wang Jingwei. The governor forbade that association from any political activity.Footnote 147

At least until 1941, the core of the Macau Chinese elite remained with Chiang, and this permitted useful communications with a very wide reach indeed. For example, in early July 1941, the British intercepted a message from Macau to the Chinese embassy at Berlin to evacuate the embassy.Footnote 148 The warning came shortly after Chongqing’s severed relations with the Axis Powers. That month, two years after his defection, Wang Jingwei saw Japan finally recognise his Nanjing government. Germany, Italy and a number of pro-Axis countries, including Spain, also recognised it.Footnote 149 Efforts were made, by Wang and Japan, to persuade Portugal to follow suit. Despite many rumours in that direction, such an official recognition never occurred. In fact, Chiang’s government asked Portugal to protect Chinese interests and citizens in Spain and its territories after the breaking of relations with Madrid, and Portugal accepted the request.Footnote 150 Despite compromises at the local level, Sino–Portuguese state-to-state relations kept an appearance of smooth continuity.

Conclusion

Although Portugal had been part of China’s diplomatic resistance against Japan since 1931, Macau’s importance for the Nationalists grew significantly from July 1937, when a continuous state of warfare led to profound and unprecedented effects in the neutral South China enclave.

When hostilities reached Guangdong province, the attitude of Portuguese colonial authorities and the actions of Chinese in Macau became an object of scrutiny and a target for mobilisation. Portuguese neutrality was often questioned by the Chinese government, but it was also pragmatically utilised by its agents. Smuggling, propaganda and meetings were conducted in and via Macau by Chinese in opposing camps. As this chapter has demonstrated, Chinese wartime diplomacy was a dynamic endeavour that did not ignore small powers such as Portugal. From the start of the war, the Nationalists used the opportunities neutrality provided, from Macau’s entrepôt features to the protection the Portuguese flag could offer renationalised ships.

Portuguese foreign policy towards China was actually nothing more than colonial policy, where every action was taken with the single objective of securing Portugal’s outposts in Asia. Whilst Chinese diplomats in Lisbon had a stable presence and acted with professionalism, Portuguese diplomats remained in occupied cities and did not follow the Nationalists to the wartime capital, Chongqing. This contributed to the disruption in state-to-state communication at a time when it was urgently needed. In such a trying context, Macau’s authorities often bypassed official diplomatic channels and launched their own shadow diplomacy initiatives, albeit without lasting success. Decisions were sometimes taken in Macau without the prior knowledge and approval of the Portuguese government in Lisbon, even though it was the latter that had to respond to Chinese enquiries and complaints over malpractices of neutrality.

Macau was part of a network of foreign-ruled territories, also including Shanghai’s foreign concessions, Hong Kong and Guangzhouwan, which, due to their ambiguous neutrality and colonial status, were used by both resistance activists and collaborators with Japan. These were liminal places, with water and overland links to mainland China, through which people, goods and information circulated. Increasing Japanese pressure to limit Chinese use of Macau for resistance had some degree of success; however, they never completely ceased as the smuggling opportunities on offer were attractive to all sides.