Fukuzawa Yukichi urged his fellow countrymen who migrated to the United States to follow the model of Anglo-American expansion – they needed to commit themselves to long-term settlement in order to have permanent achievement abroad.Footnote 1 The majority of the migrants during the last two decades of the nineteenth century, however, did not subscribe to this notion. With strong ambitions back home, the majority of Fukuzawa’s students who made their way across the Pacific at that time had no intention to live out the rest of their lives in California. Some began to return to Asia in the late 1880s.Footnote 2

The ease of migrant movement between Japan and California at the time was strengthened by another wave of Japanese migration to the United States, triggered by the Meiji government’s suppression of the Freedom and People’s Rights Movement. Initiated by the Tosa clan under the leadership of Itagaki Taisuke, this sociopolitical movement attracted many shizoku and rural elites from all over the country. It demanded the freedom of speech, the freedom of association, and the creation of a parliament in order to increase political representation for the common people. The Meiji government responded to this movement negatively. It promulgated the Public Peace Preservation Law in 1887, allowing itself to expel from the capital individuals considered detrimental to political stability and to imprison those who did not comply with this verdict of exile.Footnote 3 Thus chased out from the political center of the empire, some members of the movement chose to migrate to the United States, the nation they thought of as the true embodiment of freedom, to continue their political campaign. Using San Francisco as their base, these exiles formed the Federation of Patriots (Aikoku Yūshi Dōmei) in January 1888. They continued to criticize the political establishment in Japan by publishing periodicals in Japanese and sending copies of each issue back to Tokyo. To circumvent state censorship, they had to constantly change the names of their publications. In 1888 alone, the Meiji government banned the sale of more than twenty-one different newspapers shipped from San Francisco – a testament to the overlapping intellectual spheres in Tokyo and San Francisco.Footnote 4

A boom in the publication of trans-Pacific migration guides and writings of Japanese travelers in the United States beginning in the late 1880s further connected the minds of Japanese expansionists on both sides of the Pacific Ocean. Most of these migration guides were authored by migrants themselves, aimed at encouraging Japanese audiences to prove themselves by earning wealth and honor in the Golden State. Travelers such as Nagasawa Betten and Ozaki Yukio also provided their domestic readers with a significant amount of information about the United States in general and its Japanese immigrant communities in particular. Their writings included messages they collected from Japanese Americans as well as their own observations. In summary, before the 1980s rise of migration companies that would play a critical role in the mass migration of laborers from the archipelago to the West Coast of the United States, Japanese communities in mainland America tended to be small in size, mainly composed of self-financed students and political exiles. Even though they were now physically located in San Francisco instead of Tokyo, these settlers were well connected with thinkers and politicians back in Japan.Footnote 5

Meanwhile, the experience of the Chinese migrants who had reached the shores of North America decades before the Japanese had also shaped the minds of Japanese expansionists in Tokyo and San Francisco. On one hand, the Japanese intellectuals and policymakers saw American exclusion of Chinese immigrants as an ominous warning to get ready for the destined battle between the white and yellow races; on the other hand, they looked at the existence of numerous Chinese diasporic communities all around the Pacific Rim as both a potential threat and a possible model.Footnote 6

It was within this context of trans-Pacific dialogue between the shizoku expansionists and political dissidents that the discourse of southward expansion (nanshin), a major school of expansionist thought throughout the history of the Japanese empire, first emerged.Footnote 7 As the following pages demonstrate, if white racism forced Japanese expansionists to explore alternative migration destinations, Malthusian expansionism continued to legitimize Japanese migration-driven expansion. Both factors contributed to the construction of the nanshin discourse. The campaigns of shizoku expansion to Hokkaido and the United States together laid the ground for the initial phase of Japan’s expansion to the South Seas and Latin America.

As it was with all schools of expansion within the Japanese empire, southward expansion – both as an ideology and as a movement – was a complicated construct from its very inception. Starting in the late 1880s, different interest groups proposed a variety of agendas for expansion, their primary aims ranging from commercial to naval and agricultural. The ideal candidates for migration in these blueprints also ranged from merchants, laborers, and farmers to outcasts known as the burakumin.Footnote 8 However, the domestic struggles of shizoku settlement continued to serve as the dominant political context in which the nanshin discourse was originally proposed and debated. Like it was for the preceding Hokkaido and American migration campaigns, shizoku were initially regarded as the most desirable candidates for southward expansion.

Existing literature tends to define nanshin, literally meaning “moving into the South,” as a school of thought that promoted Japanese maritime expansion southward in the Pacific including the South Pacific and Southeast Asia.Footnote 9 This geography-bound understanding is mainly derived from the definition of Nan’yō as a geographical term in Japanese history. Literally translated as “the South Seas,” Nan’yō had different meanings in different contexts. But it has been generally considered that in its widest scope, Nan’yō covers the land and sea in the South Pacific and Southeast Asia, the two geographical regions that the works on Japanese southward expansion by Mark Peattie and Yano Tōru have focused on respectively.Footnote 10 However, as this chapter explains, for Japanese expansionists in the late nineteenth century the South Seas also included Hawaiʻi.Footnote 11 In addition to Hawaiʻi, other nanshin advocates in history did not confine their sights within the South Seas. Some also included Latin America in their blueprints of southward expansion.Footnote 12

Currently the history of Japan’s southward expansion is being studied as a subject within the nation-/region-based narrative of the Japanese empire, one that excludes the experience of Japanese migration to Latin America and Hawaiʻi.Footnote 13 However, as this chapter illustrates, the calls for expansion into Latin America and Hawaiʻi were proposed in conjunction with calls for expansion into the South Seas. The nanshin advocates envisioned that Japanese expansion to areas located geographically south to the Japanese archipelago and Japanese communities in the United States would be able to circumvent Anglo-American colonial hegemony. Following the experiences of shizoku expansion to Hokkaido in the 1870s and 1880s and to North America in the 1880s and 1890s, the campaigns for expansion to the South Seas and Latin America belonged to the same wave of shizoku expansion that was firmly buttressed by Malthusian expansionism.

Reunderstanding the World in Racial Terms

Experiences in the United States promoted shizoku migrants and visitors to adopt a race-centric worldview. Replicating the racial thinking of many expansionists in the West,Footnote 14 the Japanese expansionists’ definition of race was directly derived from Charles Darwin’s theory of natural selection. They were convinced that the world of mankind, like that of nature, not only was composed of biologically different human races but also followed the principle of survival of the fittest. The contemporary competition among nations, they believed, was a reflection of the biological struggle for the limited space and resources among the races. Their perception of the world as an arena for racial competition converged with the intellectuals in domestic Japan on whether the nation should endorse mixed residence in inland Japan (naichi zakkyo) in order to revise the unequal treaties. This would allow Westerners (as well as Chinese and Koreans) to travel, settle in, and conduct business throughout the Japanese archipelago without restriction. A group of hard-liners, later known as promoters of national essence (kokusuishugisha), warned that the white races were taking over the world by not only excluding the yellow races from the West but also invading their homelands in the East. They formed the Association of Politics and Education (Seikyō Sha) in 1888, organizing public lectures as well as publishing journals and newspapers, urging their countrymen to assume a position of leadership in the inevitable worldwide racial competition. To avoid racial extinction, they argued, the Japanese needed to compete with the white races as the leader of the yellow races; in order to emerge victorious from this competition, they must reaffirm their cultural roots and launch their own colonial expansion.

The Japanese American experience’s influence on the growing discourse of racial competition in Tokyo was particularly evident in the writings of Seikyō Sha thinker Nagasawa Betten. Nagasawa went to the United States to study at Stanford University in 1891, and there he joined the Expedition Society (Ensei Sha),Footnote 15 a political organization formed by exiled Freedom and People’s Rights Movement activists in San Francisco, and participated in their debates about the future of Japanese expansion.

Drawing from his own experience in the American West, Nagasawa wrote to his intellectual friend and fellow Seikyō Sha member Shiga Shigetaka about the importance of adopting a race-centric worldview:

While the competition between nations is evident, the competition between races remains invisible. People take the visible competition seriously and prepare themselves for it, but only experts can sense the invisible competition and thus few efforts are made for its preparation. The crucial point lies not in the former but the latter. … Living among people of other races, my sense of urgency about the need for making preparations for racial competition grows each day. The urgent task now, as you have proposed, is to promote our national essence and to inspire our countrymen’s spirit of overseas expansion.Footnote 16

Nagasawa thus shifted the primary subjects of global competition in expansion from nation to race, the power of which was not bound by national territory. This view allowed him to place overseas migration at the center of Japanese expansion. He concluded, “Overseas expansion is the most effective way to prepare for racial competition. … Once our fellow Japanese find their footing in every corner of the world, it will doubtlessly lead to our triumph in the racial competition.”Footnote 17 In his book The Yankees (Yankii), published in Tokyo in 1893, Nagasawa Betten embraced American frontier expansionism and described the national history of the United States as a living example of it.Footnote 18 The Mayflower ancestors of the American people, he wrote, overcame many hardships to establish the first thirteen colonies as the foundation of their nation, and their expansion had not ceased ever since. The American borders had extended beyond the Mississippi River and the Rocky Mountains, reaching the coast of the Pacific Ocean. If the railway bridging the two Americas were completed, the United States would become a natural leader of the entire Western Hemisphere due to the wisdom and wealth of its people.Footnote 19 While Nagasawa did not believe that Japanese overseas expansion was triggered by religious and political persecutions, he argued that the Japanese should nevertheless emulate the Mayflower settlers’ frontier expansionism in order to establish a new, large, prosperous, and mighty nation much like the United States.Footnote 20

However, in this trans-Pacific reconstruction of Japanese expansionism, Anglo-American settler colonialism was not the only reference for the Japanese intellectuals. The omnipresent influence of Chinese Americans on their lives in San Francisco led the Japanese expansionists to include the Chinese expansion model as another point of reference. The existing literature on Japanese American history has well documented the fact that the Japanese immigrants replicated white racism toward their Chinese neighbors in the American West. To combat white racism, they strove to prove their own whiteness and spared no efforts to separate themselves from the “uncivilized” Chinese laborers.Footnote 21

This attitude, however, constituted only one aspect of the Japanese migrants’ complicated feelings about their Chinese counterparts in the late nineteenth century. Arriving in the American West decades earlier than the Japanese, the Chinese immigrants founded the earliest Asian communities that the first Japanese immigrants readily resided in.Footnote 22 While shizoku setters felt insulted when they were mistaken for Chinese, they also admired Chinese achievements in the land of white men. Mutō Sanji, a Japanese business tycoon who sojourned in the United States during the Meiji era, published a guide for Japanese migration to the United States in 1888. In this book, he argued that in the destined global competition between the white and the yellow races, the Chinese had offered a good example for the Japanese on how to compete with the white races.Footnote 23

Mutō’s book went into detail illustrating the contributions that Chinese immigrants had made to American society in the fields of agriculture, mining, railway building, manufacturing, and domestic service.Footnote 24 He also commented on the strong presence of Chinese communities on the West Coast of North America: no matter where he traveled, be it California, Oregon, Washington, or British Columbia, he could always find Chinese communities there. Admiring “the courage of the Chinese in competing with the white people,”Footnote 25 Mutō believed that the Japanese should borrow a page from the successful Chinese experience.Footnote 26

Compared to Mutō, Nagasawa was more critical of the Chinese American immigrants. He wrote extensively about what he saw as “uncivilized” behaviors of the Chinese in the United States that his fellow countrymen should take care to avoid. Even so, he still acknowledged the wide-reaching presence of Chinese migrants around the world and saw the Chinese as another rival for the Japanese in the competition of expansion.Footnote 27

In summary, although Meiji settlers and travelers shared a discriminatory attitude toward the Chinese immigrants in the United States, at the same time there was also a sense of both admiration and fear. This mixed attitude reflected the general perception of the Qing Empire among Japanese intellectuals prior to the Sino-Japanese War, when it was considered to be a mighty geopolitical power in Asia, declining but still maintaining a strong potential for revival. Some Meiji Japanese intellectuals, Seikyō Sha thinkers in particular among them, espoused a type of proto Pan-Asianism and recognized the Qing Empire as the current dominating power in Asia; it was only in escaping from the Qing’s clutches that Japan could win for itself the mantle of leadership in Asia.Footnote 28

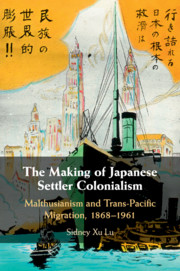

Figure 2.1 This picture appears in the front matter of the book Beikoku Ijū Ron authored by Mutō Sanji in 1887. Based on his observation in the American West, Mutō described the global competition of the world in this picture as the “conflict of races” among the Caucasians, the Chinese, and the Japanese.

For Japanese expansionists on both sides of the Pacific, the Qing Empire was a mighty rival in the age of colonial competition. At the same time, however, Qing was also seen as a possible ally whose model of expansion Japan could learn from. Such an understanding of the Qing Empire and Chinese overseas expansion substantially affected the ways in which the racial exclusion of Chinese immigrants in the United States transformed the ideology of Japanese expansionism in the last two decades of the nineteenth century.

Chinese Exclusion in the United States and the Rise of Nanshin

The first Chinese Exclusion Act was enacted by the US government in 1882, before most of the Japanese migrants had arrived in California. Anti-Chinese campaigns made it possible for the act to be renewed for another ten years in 1892 with the Geary Act, then becoming permanent in 1902.Footnote 29 The complexity of the Japanese racial identity, especially when considered in relation to that of the Chinese and white Americans, resulted in different responses to the Chinese Exclusion Act among the Meiji expansionists on both sides of the Pacific. Some of them unconditionally accepted the act’s racist logic and believed that the uncivilized Chinese deserved to be excluded, at the same time emphasizing that the Japanese belonged to the civilized races and therefore would not suffer the same fate as the Chinese.Footnote 30 The “uncivilized Chinese” also served as a metaphor that the shizoku settlers used to disparage the unprivileged Japanese laborers who began to arrive in California en masse at the beginning of the 1890s. Asserting that these laborers’ behaviors were almost as uncivilized as those of the Chinese, the Japanese intellectuals believed that their lower-class countrymen in the United States had dishonored the empire, leading to the argument that their migration should be restricted if not outright banned.Footnote 31

Some other expansionists, however, contemplated the fate of the Chinese in the United States with a measure of empathy. An 1888 editorial in the Nineteenth Century (Jūkyūseiki), a mouthpiece of the Federation of Patriots, identified the Qing Empire and the Empire of Japan as the two leaders of East Asia, both of whom had to face the invasion of white people who were armed with civilization and gunpowder. The article warned its readers that even the Qing Empire, with its vast territory, great wealth, and over three hundred million subjects, could not avoid falling prey to white imperialism. Since these same Western powers would not spare Japan from its imperialistic clutches, it went on to argue, Japan should develop its material strength in order to survive through self-defense instead of worshipping Western nations.Footnote 32

Some were further convinced by a series of anti-Japanese incidents in California at the end of the 1880s that the Japanese would eventually meet the same fate of racial exclusion as the Chinese immigrants had. Japanese diplomats in the United States began to send Tokyo copies of articles in local newspapers that called for excluding the Japanese from immigration because they were no different from the uncivilized Chinese who stole jobs from white workers.Footnote 33 In 1891, the US government established the Immigration Bureau and imposed strict immigration rules in order to exclude “undesirable” individuals from coming to the United States.Footnote 34 This wave of anti-Japanese sentiment reached its peak in 1892, marked by a sharp increase in the number of articles attacking Japanese immigrants in major San Francisco newspapers.Footnote 35 Exclusionists also began to give public speeches and hold gatherings all around the city. With the rise of Japan’s colonial empire in Asia, the flow of Japanese laborers into California was considered an even greater threat than the Chinese had posed.Footnote 36

In the same year, an editorial in Patriotism (Aikoku), another official newspaper of the Federation of Patriots, responded to the anti-Japanese sentiment in the United States with a blistering attack on white racism: “Extremely wretched! Extremely cruel! On the coast of Africa, when a ship steered by white people ran out of coal, they captured the natives and threw them into the fire as fuel. … The white people also captured native African children and used them as baits to hunt crocodiles. Once a crocodile took the bait, the child would die in its stomach. This is the way that the white races treat colored races. How cruel! How wretched!” The article then argued that white Americans treated the Chinese immigrants in a similar manner. The Americans had excluded the Chinese from their territory while invading the latter’s home country with gunpowder, costing the Chinese countless lives and untold amounts of wealth. While the Europeans’ massacres of Africans were cruel, the article claimed, “they are still forgivable when compared with what the Americans are doing today: they are bragging about their civilization to the entire world, but how can they do so when they are full of cruelty and prejudice?!” It then moved on to argue that the Japanese in the United States suffered from white racism as well and that the Japanese government should send the Imperial Navy to defeat the white Americans in retaliation against such humiliations.Footnote 37

The expansionists in Tokyo, however, had little interest in waging an actual war against the United States. The Chinese Exclusion Act and their fear that the Japanese would eventually meet the same fate pushed them to try to make sense of the exclusionists’ logic. Some took the Chinese exclusion as an announcement that the white races had secured their ownership of the North American land and thus had the right to exclude others. As a result, the United States was no longer a suitable destination for Japanese migration. Instead, the Japanese should make haste to occupy hitherto unmarked and unowned territories in the world; once they staked their claims of ownership, they could exclude other races just like the white Americans were now doing. Of course, in the minds of these Meiji expansionists, only the “civilized” races qualified as competitors for land ownership. Aboriginal peoples, such as Native Americans and Pacific Islanders like the Ainu in Hokkaido, were classified as uncivilized races who had no right to their ancestral homes.

An 1890 article vividly captured this moment of transformation in the discourse of Japanese expansionism. Authored by political journalist Tokutomi Sōhō, it was titled “The New Homes of the Japanese Race” (“Nihon Jinshu no Shin Kokyō”). Tokutomi began by reaffirming the importance of race in global politics: nations no longer struggled through military aggression but through race-centered colonial expansion. The Chinese were an example of a race that had spread to every corner of the world. While the Chinese migrants’ status in local societies was usually low, they nevertheless added to the overall strength of their race. As a result, even though the Qing Empire was declining, the power of the Chinese race was in fact increasing because they continued to migrate overseas and increase in numbers there.

Tokutomi’s call to emulate the Chinese in the quest for Japanese expansion was grounded in Malthusian expansionism. He believed that the Japanese, like the civilized Western nations, were an expanding race marked by a rapidly growing population. The Japanese empire urgently needed to join the global racial competition by exporting its surplus population overseas and turning them into trailblazers of racial expansion. Where, then, could the Japanese expand to? He named the Philippines, the Mariana Islands, the Carolina Islands, and many other islands dotted across the Pacific Ocean as the ideal targets. Tokutomi was not bothered by the facts that the majority of these areas were already colonized by European powers. Appropriating the Lockean logic used to justify Japanese settlement in the American West, Tokutomi believed that the white Europeans failed to claim their ownership over many of these areas because the land was left empty and unused. Aside from tropical flora and fauna, these islands were inhabited only by primitive barbarians. Once the Japanese actually claimed these “empty houses,” Tokutomi argued, they could “shut the doors on everybody else.”Footnote 38

As a direct result of Chinese exclusion in the United States, the call for southward expansion also garnered supporters in the Japanese government. A particularly noteworthy supporter was Enomoto Takeaki, whose many roles in the government included a stint as minister of foreign affairs between 1891 and 1892, a time when the flood of consular reports about anti-Japanese political campaigns in California began to reach Tokyo. Responding to white racism on the other side of the Pacific, Enomoto established the Bureau of Emigration as a part of his ministry in 1891 to explore vacuum domicilium around the Pacific as alternative targets for Japanese expansion.Footnote 39 In the 1880s and 1890s, he played a crucial role in founding two schools of thought that together constituted the overall nanshin discourse – the expansion to the South Seas (Nan’yō) and the expansion to Latin America.

While the existing academic literature has clinically isolated the history of Japanese maritime expansion to the South Seas from the history of Japanese migration to Latin America, as the following pages will demonstrate, they were closely associated with each other in terms of both ideology and practice. A sense of urgency in searching for “unclaimed” territories, triggered by both white racism in North America and trans-Pacific migration of the Chinese, pushed the Japanese expansionists to cast their gaze southward on both the land and sea in the tropic zone and Southern Hemisphere. This wave of expansion also traced its ideological and political lineage back to the shizoku expansion into Hokkaido in the earlier decades.

Hawaiʻi and Calls for Expansion in the South Seas

Tokutomi’s proposal was a part of a larger intellectual trend that pointed to the South Seas as the future of Japanese expansion. Throughout the history of the empire, Japanese thinkers had offered a variety of rationales for southward expansion into the Pacific, ranging from defending the archipelago against foreign invasion to protecting Japanese subjects abroad through naval power, from stretching the trans-Pacific trade network to fulfilling Japan’s own Manifest Destiny as a maritime empire.Footnote 40 Originally, however, the call for southward expansion was promoted by Seikyō Sha thinkers in the latter half of the 1880s as a direct response to the Chinese Exclusion Act in the United States.

Though relatively obscure, the earliest nanshin promoter was a Seikyō Sha thinker named Sugiura Jūkō.Footnote 41 In a book published in 1886, he argued that Japan was facing serious threat from the West and it could only survive through conducting its own colonial expansion. Sugiura saw that the Chinese migrants in North America were humiliated and excluded by the Anglo-Saxons. Worried that the Japanese migrants would eventually receive the same mistreatment in the world of the white settlers, he believed that the Japanese should look elsewhere to expand. According to him, the Qing Empire and Korea were to be Japan’s allies, Southeast Asia was already claimed by the British and French, thus the only places where the Japanese could build colonies were the numerous islands located to the South of the Japanese archipelago in the Pacific.Footnote 42

The book Nan’yō Jiji, authored by Sugiura’s fellow Seikyō Sha member Shiga Shigetaka one year later, infused further political meaning into the word Nan’yō, which was previously only a loosely defined geographical concept. For Shiga, Nan’yō indicated the cultural space lying to the South of the Japanese archipelago independent from both the West (Seiyō), the white men’s domain, and the East (Tōyō), home of the yellow races.Footnote 43 While a substantial part of Nan’yō was still unclaimed, Shiga warned that the white colonists had already begun their territorial scramble there; it was vital for the Japanese to enter the fray as soon as possible.

In particular, Shiga singled out Hawaiʻi, a wealthy kingdom that already had thousands of Japanese migrants, as a target worthy of Tokyo’s attention. Though Hawaiʻi was officially independent, the land and politics of the kingdom were monopolized by the white settlers while its small business and farming sectors were controlled by the Chinese. Shiga argued that Japan should also claim a share of the prize by sending more migrants to Hawaiʻi and enhancing Japan’s commercial power there.Footnote 44

In the same year when Nan’yō Jiji became a bestseller in Japan, American settlers in Hawaiʻi forced the Hawaiʻian King Kalākaua to sign a new constitution that deprived the all nonwhite migrants – as well as two-thirds of the native Hawaiʻians – of their voting rights. Hawaiʻi, a book pushed in 1892 in Japan, argued that this constitution sent a clear message that the white people had already gained the upper hand in the racial competition in the Hawaiʻian Islands. After the Americans took full control of Hawaiʻi, the book warned, they would shut its doors to the Chinese and the Japanese.Footnote 45 It reminded its readers that the Japanese empire could not afford losing its influence in Hawaiʻi: though small in size, Hawaiʻi was the center of communication and trade between the two sides of the Pacific Ocean and thus the center of the racial competition in the Pacific region.Footnote 46

A year later, the American settlers overthrew the Hawaiʻian monarchy and replaced it with a republic. Fearing that Hawaiʻi might soon entirely fall into the white men’s hands, the Japanese Federation of Patriots in San Francisco dispatched four of its members to Hawaiʻi to make an attempt at retaining the Japanese residents’ voting rights and dismantling the white men’s monopoly of power in Hawaiʻian politics.Footnote 47 They published a book titled Japan and Hawaiʻi (Nihon to Hawai) in Tokyo that recorded their observations and thoughts while in Hawaiʻi. The book urged the Japanese government to seize the “golden chance” of the political upheaval on the islands and use forceful diplomacy, backed up with naval power, to win political rights for Japanese settlers in Hawaiʻi. Given the geopolitical significance of the islands, Japan had to secure its interest there in order to fight the race war with the West. In addition to arguing for Tokyo to exert political pressure, Japan and Hawaiʻi also suggested that the Japanese government should follow the model of the Chinese immigrant companies in San Francisco by purchasing land on the islands and cultivating Japanese enterprises there.Footnote 48

In the same year, Nagasawa Betten echoed the opinion of the Federation of Patriots members in Seikyō Sha’s mouthpiece Ajia, emphasizing the importance of Hawaiʻi in the racial battle that loomed over the Pacific Ocean.Footnote 49 In his book The Yankees, also published in 1893, Nagasawa pointed out another advantage that would come from controlling Hawaiʻi: it would serve as a station for the Japanese empire in the mid-Pacific region and allow it to further expand into Latin America.Footnote 50

Calling for Expansion in Latin America

The Yankees also served as a telling example of how the discourse of Japanese colonial expansion into the South Seas was closely tied to another expansionist discourse emerging around the end of the 1880s, one that called for Japanese migration to Latin America. Much like the case of the South Seas, the promotion of expansion into Mexico and further south in the Western Hemisphere was a collective response made by Japanese expansionists in Tokyo and San Francisco to the Chinese Exclusion Act in the United States, which they viewed as an episode in the colonial contest between different races.

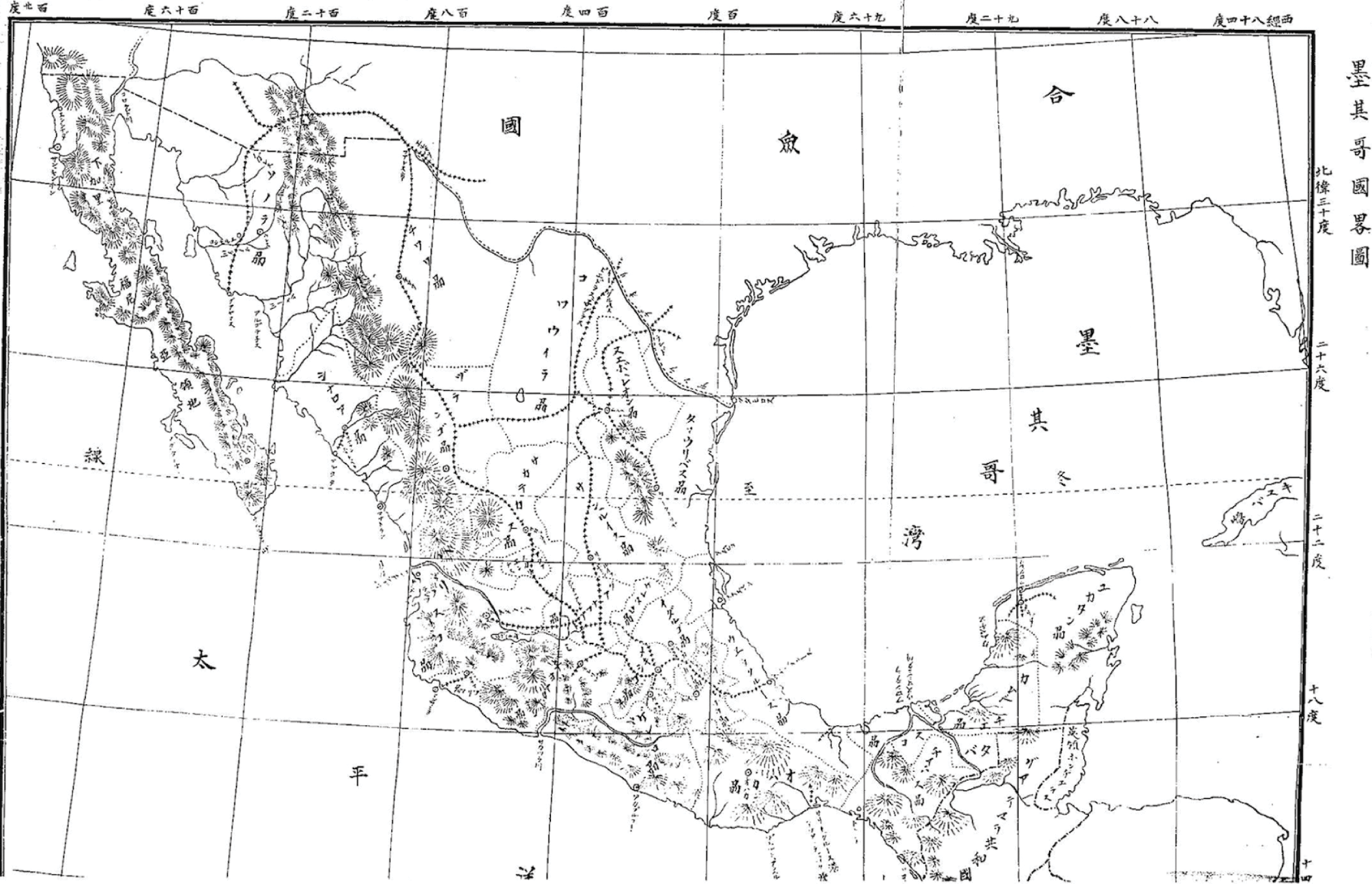

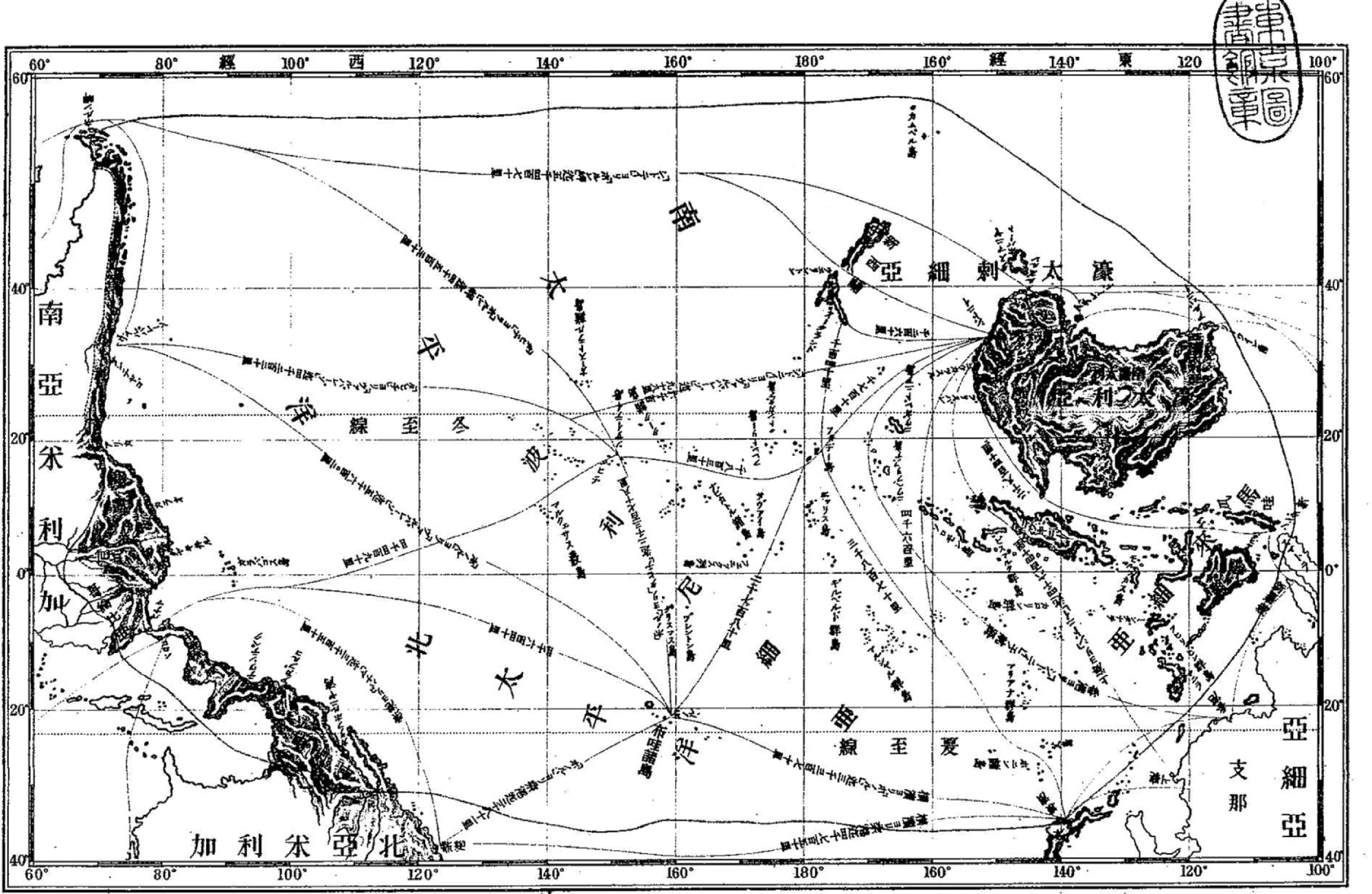

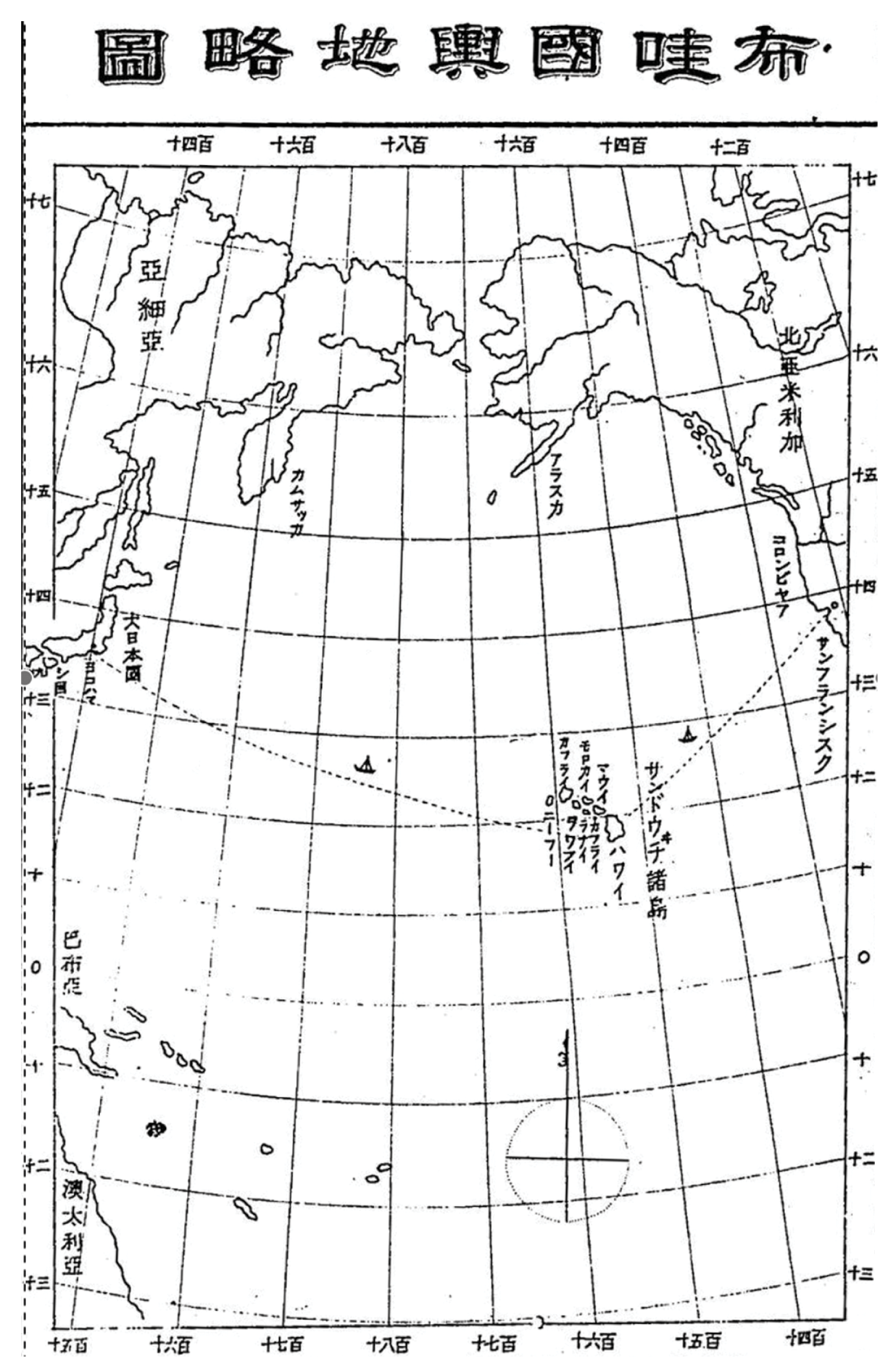

Figure 2.2 This map appears in Hawai Koku Fūdo Ryakuki (A Short Description of the Society and Culture of the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi), one of the earliest books published in Meiji Japan introducing the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi to the general public. The map describes the importance of Hawaiʻi by highlighting its location at the center of the sea route connecting Japan and the American West Coast. It demonstrates that Japanese colonial ambition in Hawaiʻi was developed hand in hand with Japanese migration to the American West.

Substantial efforts in promoting migration to Latin America began when Enomoto Takeaki became minister of foreign affairs in 1891. The same year, Enomoto established the Japanese consulate in Mexico City, collecting local information in order to facilitate migration planning. He assigned Fujita Toshirō, a previous Japanese consul in San Francisco whose reports had flooded Enomoto’s office in Kasumigaseki, warning about the possibility of Japanese exclusion in California, to head the consulate in Mexico. Later that year, Enomoto sponsored Fujita to conduct a trip with a few other government employees to investigate locations in Mexico suitable for Japanese migration.Footnote 51 These activities illustrated the direct connection between the Chinese Exclusion Act in the United States and Enomoto’s initiative in exploring Mexico as a possible destination for Japanese migration. Such a connection was further asserted by Andō Tarō, the first director of the Emigration Bureau appointed by Enomoto himself. In 1892, Andō published a series of articles aiming to steer the general public’s attention toward migration to Mexico. Given the fact that the Asian immigrants in the United States were mistreated due to white racism, Andō told readers, Mexico was a more desirable destination for migrants from the overpopulated Japan because there “the natives welcomed us thanks to our racial affinity.”Footnote 52

Enomoto’s initiative mirrored the rise of discussions about expansion into Latin America among the Japanese settlers in the United States. Disillusioned by white racism, some of them gave up on the dream of pursuing a Japanese colonial future in the American West. As an 1891 Ensei article lamented, white sellers not only prohibited the Japanese from establishing colonies in the United States, but also refused to treat Asian immigrants equally. The real Promised Land for the Japanese, it argued, lay to the south of the US border. Latin America had vast amounts of fertile land, and its natives were nothing like the white Americans – they were welcoming and obedient, easy for the Japanese to manipulate.Footnote 53 That year, Ensei began to publish reports of self-organized Japanese American expeditions to Mexico and South America. These reports offered Japanese American readers detailed information about Latin America’s geography, culture, and social conditions, encouraging them to remigrate southward across the US border.Footnote 54

In this trans-Pacific chorus clamoring for Latin American migration, the Chinese migrants, who were the actual objects of racial exclusion in the United States, also played a role. As they had done in the case of Japanese migration to the American West, Japanese expansionists used the Chinese experience in Mexico as a reference point to make their own proposals. In fact, it was the Chinese presence in Mexico that encouraged Japanese expansionists to view Mexico as a potential target in the first place. To promote expansion to Mexico and farther south, Nagasawa Betten argued in 1893 that the Chinese, being excluded from North America, Hawaiʻi, and Australia, were now moving into Mexico and South America. In order to avoid ceding these lands to Chinese control, the Japanese should occupy them first.Footnote 55

Andō Tarō urged his fellow countrymen to learn from the Chinese example and pursue their future in Mexico. He argued that while the Japanese shied away from setting their feet on welcoming foreign lands, their fellow Asians were building “small Chinese nations” all over the world under adverse circumstances.Footnote 56 An article in Ensei further predicted that while the Qing Empire might collapse in the near future, the Chinese would remain as a powerful race in the world because of their omnipresent diasporic communities in Latin America and Southeast Asia; they would be a very important force for the Japanese to collaborate with in order to win the race war against the white people.Footnote 57

In sum, the Chinese trans-Pacific migration and its exclusion from the white men’s world served as both a reference and a stimulation for the rise of Japanese expansion in the South Seas and Latin America. But as the remaining pages in this chapter illustrate, the shizoku expansion in Hokkaido during earlier decades also provided intellectual and political foundations for southward expansion.

From North to South: Hokkaido and Nanshin

If the discourse of racial competition had shaped the practical direction of the expansion, it was the ideology of Malthusian expansionism that provided the logical foundation for the project. Malthusian expansionism emerged with the colonial project in Hokkaido and early Japanese migration to the United States. It argued for both the existence of surplus population and the necessity of further population growth, the apparent paradox of which was to be solved by migration-based expansion. At the end of the 1880s, the South Seas and Latin America became new destinations where Japan’s surplus population could be exported to.

In 1890, economist Torii Akita announced that Japan had seen a population increase numbering six million in the preceding fifteen-year period. He warned that with such a rapid rate of population growth and a small territory, the Japanese would soon become plagued by hunger and homelessness. Directly spending government money to relieve poverty would lead to a financial deficit, but reducing the birth rate by moral persuasion (as Thomas Malthus had suggested) might lead to a permanent decline of the racial stock. Instead, the nation should make long-term plans by moving the surplus people elsewhere to explore empty and fertile lands. Through two lists that outlined population density figures in different prefectures in Japan and different areas in the world, Torii identified the ideal destinations for migration as Hokkaido within Japan and the South Seas as well as the two Americas abroad.Footnote 58

However, outside of Torii’s thesis, the arguments for migration to Hokkaido and overseas did not always complement each other. The racism that Japanese migrants and travelers encountered in the United States since the late 1880s and the white plantation owners’ poor treatment of Japanese laborers in Hawaiʻi triggered renewed calls for migration to Hokkaido in place of going overseas.Footnote 59 Such arguments played down the value of overseas migration in general by emphasizing that Hokkaido had the capacity to host all of Japan’s surplus population. In a public lecture in 1891, Hamada Kenjirō argued that overseas migration would run the risk of harming Japan’s national image and might result in material losses as well as diplomatic issues for the nation. Reminding his audience that the population density in Hokkaido was still extremely low, he argued that it would be beneficial to the nation if the surplus people would be used to explore Hokkaido instead of being exported abroad.Footnote 60 In the same year, Katsuyama Kōzō also opposed overseas migration by claiming that the Japanese people, due to their long history of isolation, were not yet used to living abroad. Hokkaido, he believed, was the ideal migration destination because it was a part of Japan’s domestic territory and its vast lands, rich and fertile, were fully capable of accommodating all the surplus population to be found in the archipelago.Footnote 61

Responding to these arguments, advocates for overseas migration disputed the assertion that Hokkaido could fully accommodate the archipelago’s ever-growing surplus population. In his book Strategies for the South (Nan’yō Saku), southward expansionist Hattori Tōru argued that the advocates for domestic migration were wrong to believe that Hokkaido was sufficient to host all surplus people within Japan proper. He reasoned, “The Japanese population is growing at an astonishing rate. … In 50 years, there will be 25,000,000 newborns in the archipelago. Since Hokkaido can only accommodate 9,150,000 more people, it means that Hokkaido’s capacity will be filled to full within 20 years.”Footnote 62 Hattori reminded his readers that based on his calculations, in order to make long-term plans for the country, they needed to think beyond Hokkaido and look overseas for migrant destinations. Ironically, the idea of looking for extra space to export the surplus population, originally drawn from the Hokkaido expansion, was now used against the same enterprise.

As it was with the colonial project in Hokkaido, however, the urgent necessity of exporting surplus population overseas was proposed in conjunction with the goal of promoting further population growth and wealth accumulation. Hattori pointed out that since nations competed with each other via racial productivity and the ability of expansion,Footnote 63 to gain the upper hand in this competition Japan should export its subjects from the overcrowded archipelago to the islands in the South Seas and build colonies there. The migration would not only stimulate further increases in Japan’s manpower but also facilitate a transfer of natural resources from the colonies to the metropolis, expanding the nation’s trading networks.Footnote 64 Mexico was also incorporated into the map of expansion by the same logic.Footnote 65 Similar to shizoku expansion in Hokkaido and the United States, it was the need for surplus population not the fear of it and the celebration of population growth not the anxiety over it that buttressed the discourses of expansion to the South Seas and Latin America. The three dimensions of Japanese colonial expansion shaped by the empire’s imitation of Anglo-American settler colonialism, including making useful subjects, uplifting the Japanese in the global racial hierarchy, and increasing capitalist accumulation for the empire, continued to shape ideas and practices during this new wave of expansion.

Making Useful Subjects

The idea of using migration to produce more valuable subjects was embraced and further developed under the discourse of racial competition. Seikyō Sha thinkers saw Japan’s own colonial migration as a necessary step to prepare the empire builders for their destined war with the white races. Shiga Shigetaka, for example, saw the Chinese Exclusion Act as evidence that the yellow races, including the Japanese, were not yet mentally and physically ready to compete with the white people head-on.Footnote 66 In order to avoid defeat, Japan should not only prohibit interracial residence in the archipelago but also export its subjects. Such a move, he further argued, would enable these subjects to acquire both knowledge of the outside world and an expansionist spirit.Footnote 67 Connecting nationalism with overseas expansionism, “the true patriots,” he asserted, were those “who left the country for country’s good.”Footnote 68 For Nagasawa Betten, Hawaiʻi would be the first stage to test the Japanese race’s ability to compete with the Caucasians. Gaining political rights in Hawaiʻi would allow Japanese immigrants to compete with the white settlers equally. This was the first test for the Japanese, the result of which could determine whether interracial residence should be allowed in Japan.Footnote 69 Even Taguchi Ukichi, who directly opposed the Seikyō Sha thinkers on the issue of interracial residence and was confident that Japanese were already fully capable to compete with Westerners, agreed that migration to the South Seas would better prepare the Japanese for the upcoming race war. Though previously lacking expansionist experience, he pointed out the Japanese could acquire a hands-on education on the subject in the South Seas.Footnote 70

The expansionists had a well-defined profile of the ideal migration candidate. While some of them were open to the idea of merchants, peasants, and even burakumin going overseas, shizoku were the most ideal candidates for this project. Throughout the 1880s and into the early 1890s, shizoku relief remained the overarching political context for Japan’s overseas expansion. Similar to the case of Hokkaido in the 1870s, the expansionist thinkers believed, the South Seas and Latin America would turn the declassed samurai into self-made men and model subjects of the empire. Taguchi Ukichi, for example, began his promotion of southward expansion by accepting a special shizoku relief fund from the governor of Tokyo. In 1890, this fund allowed him to establish and manage the Southern Islands Company (Nantō Shōsha) in the Bonin Islands that provided employment for shizoku from the Tokyo prefecture.Footnote 71 Taguchi also used a part of this fund to embark upon a six-month trip to Micronesia in the same year, investigating possible opportunities for shizoku there.Footnote 72 Relocating “ambitious Tokyo shizoku to the South Seas,” he believed, would enable them to achieve self-independence and expand Japan’s power abroad at the same time.Footnote 73

While Taguchi’s activity in the South Seas did not last long, his passionate writings in Tokyo Keizai Zasshi brought the topic of South Seas expansion into the public discourse of the day.Footnote 74 He argued that southward expansion, like its Hokkaido counterpart, should be commerce based and free from governmental intervention. He believed that early Meiji migration to Hawaiʻi failed to benefit the empire because the impoverished farmer-migrants, lacking a spirit of independence, eventually became enslaved by Westerners.Footnote 75 With this historical lesson in mind, Japan’s southward expansion should be conducted by independent merchants. Such a mercantile expansion would not only bring tremendous profit to Japan but also allow the empire to acquire unclaimed territories in the Pacific in a nonmilitary manner.Footnote 76

While Taguchi redirected shizoku expansion from Hokkaido to the South Seas, his intellectual opponent on Hokkaido migration policies, bureaucrat and scholar Wakayama Norikazu, was a central figure in the campaign that brought Latin America to the map of shizoku expansion. Maintaining his migration agenda in Hokkaido, Wakayama believed that Japan’s expansion into Latin America should be conducted not through commerce but rather through government-led agricultural settlement. In a letter to Ōkuma Shigenobu, minister of foreign affairs, Wakayama urged the government to mobilize a million shizoku to explore Latin America and establish colonies there. These colonization projects, he contended, would strengthen shizoku in both body and spirit. With appropriate education that would ensure their continued loyalty to Japan, these settlers would become permanent assets of the Japanese empire.Footnote 77

Racial Uplifting

As it was in the case of Hokkaido expansion, the nanshin proposals cited Japanese population growth as a fact that proved the superiority of the Japanese race. The South Seas expansionists contrasted Japanese population growth with a rapidly declining native population, painting an image of an empty space waiting for the expanding Japanese to rightfully occupy.

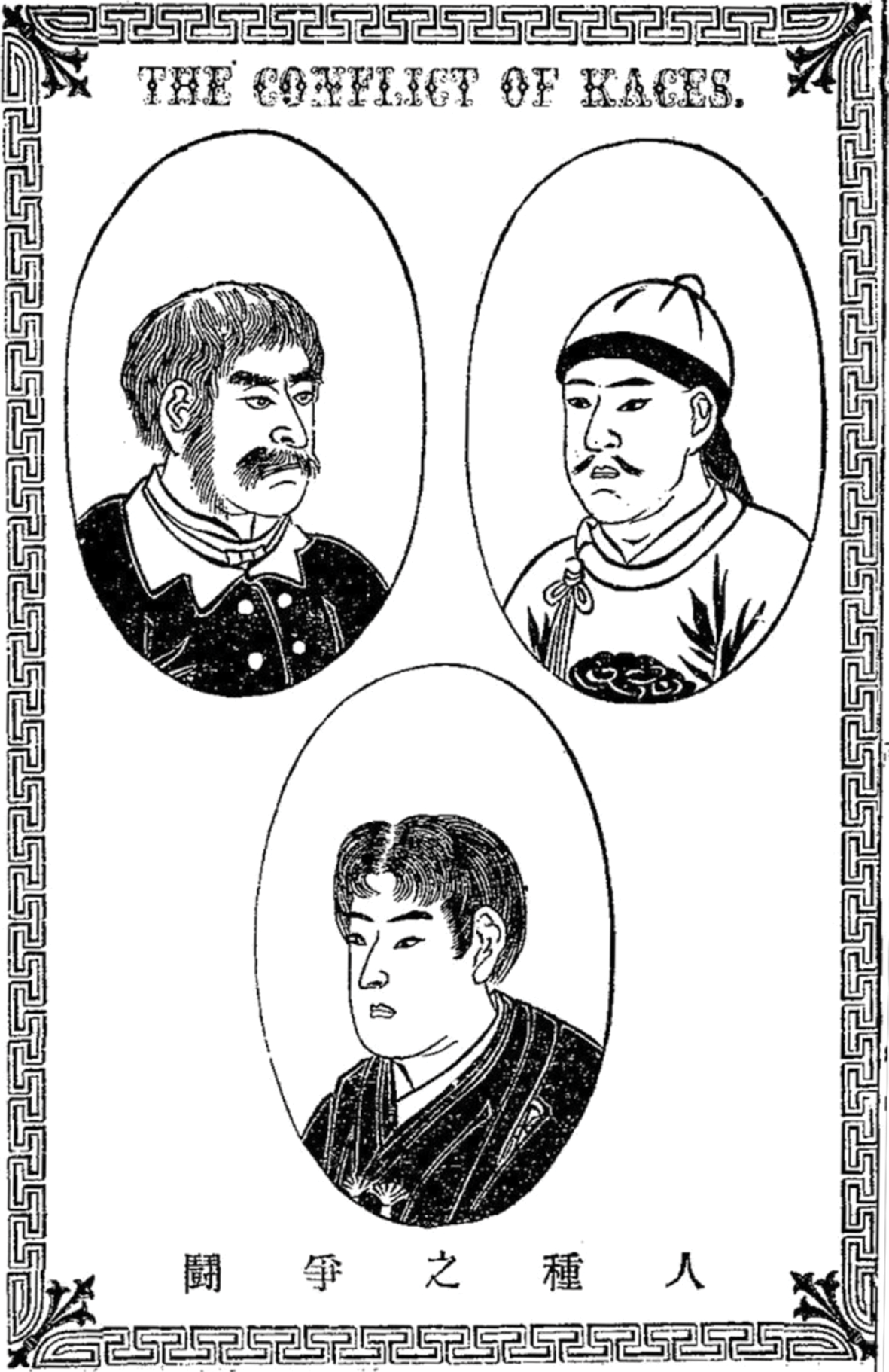

Figure 2.4 This picture appears in the front matter of a book that recorded the observations of a group of Japanese expansionists during their expedition to Mexico. It describes the primitivity of Mexican farmers.

Japan’s colonial experience in Hokkaido also enabled the South Seas expansionists to place the Japanese in the existing racial hierarchy between the white colonists and native islanders as another civilized race. Shiga Shigetaka, for example, found similarities between the native islanders of the South Seas and the Ainu of Hokkaido, categorizing both as inferior in relation to the Japanese and Westerners. He attributed the decline of the native population to their own racial inferiority – they lacked the ability to withstand epidemics and were incapable of competing with white settlers.Footnote 78 As an adherent of social Darwinism, he saw such racial decimation as cruel but unavoidable and believed that the Japanese, as a superior race, should claim their share in the South Seas like the Westerners.Footnote 79 On the other hand, unlike the Ainu and the Pacific Islanders who were doomed to disappear, the local peoples in Latin America were not categorized as primitive races. However, they were still considered to be inferior to the Japanese; thus the latter could easily settle on their lands and bring the light of civilization to them.Footnote 80

Increasing Capitalist Accumulation

Also similar to the case of Hokkaido, in the minds of Japanese expansionists, the declining and/or inferior natives in the South Seas and Latin America were juxtaposed with the abundant wealth these lands could provide for the empire. Sugiura Jūgō, for example, was amazed by the South Seas’ low population density in contrast with the enormous amount of raw materials it provided for England.Footnote 81 In an article titled “Economic Strategies in the South Seas” (“Nan’yō Keiryaku Ron”), Taguchi Ukichi’s most representative thesis on South Seas expansion, he similarly perceived the islands “below the equator” as “not only full of precious plants, animals, and rare minerals, but also rich in marine products.”Footnote 82

Advocates for migration to Latin America viewed their proposed destination in much the same way. Listing a series of data that compared the populations, territory sizes, and natural resources between Japan and Mexico, Tōkai Etsurō contrasted a small, resourceless, and overcrowded Japan with a spacious, wealthy, and empty Mexico. As the title of his book indicated, expansionist migration to Mexico was a “strategy to enrich the Japanese nation” (nihon fukoku saku). By the book’s end, Tōkai had drawn a similar portrait of several other Latin American countries such as Columbia, Honduras, Brazil, and Chile, all of which were listed as possible future migration destinations for his countrymen.Footnote 83

As the empire’s first colonial acquisition, Hokkaido was constantly mentioned as a point of reference in the expansionists’ descriptions of the South Seas and Latin America. Japanese Malthusian expansionists perceived native islanders as the equally primitive brethren of the Ainu. They identified the northern island of New Zealand, in particular, as similar to Hokkaido in terms of both ecology and economic potential.Footnote 84 They considered Latin American countries even more desirable than Hokkaido due to their larger and more fertile territories, more abundant mineral deposits, and better climate in general.Footnote 85 Through these comparisons, Japanese expansionists portrayed the South Seas and Latin America as new sources of wealth (shin fugen) that were similar to or even richer than Hokkaido. Their empty lands offered a perfect solution to the issue of overpopulation in the archipelago, and their limitless resources would help to sustain the ever-expanding empire.Footnote 86

Human Connections

Aside from ideological consistency, the innate continuity shared by the Hokkaido and nanshin campaigns was also demonstrated by extensive human connections between the two. Both Taguchi Ukichi and Wakayama Norikazu, architects of the Hokkaido expansion project in the 1870s, became proponents of southward expansion in the late 1880s. They did so with different destinations in mind – Taguchi in favor of the South Seas and Wakayama arguing for Mexico – but it was Enomoto Takeaki who lent his political influence and personal efforts to both southward projects.

After serving as a high-ranking officer in the Hokkaido Development Agency, Enomoto rose to a series of key cabinet positions. He was successively in charge of the Ministries of Communications (1885–1889), Education (1889–1890), Foreign Affairs (1891–1892), and finally Agriculture and Commerce (1894–1897).Footnote 87 Believing that national strength could be acquired only through frontier conquest and colonial expansion, Enomoto made a few unsuccessful attempts to expand the empire into the South Seas by purchasing the Mariana Islands, the Palau Islands, and Borneo as early as the mid-1870s.Footnote 88 To promote studies on the Pacific Rim region with colonial ambitions in mind, he helped to establish in 1879 the Tokyo Geography Society (Tokyo Chigaku Kyōkai), modeled after the Royal Geographic Society in London.Footnote 89 The society’s members included leading intellectuals and politicians of the day such as Shiga Shigetaka, Fukuzawa Yukichi, and Ōkuma Shigenobu. With his influence in the Imperial Navy, Enomoto also encouraged the Japanese intellectuals’ interest in the South Seas by sponsoring trips via naval cruises. A number of Seikyō Sha expansionists took this opportunity to tour the South Seas, among them Miyake Setsurei and Shiga Shigetaka, the latter of whom wrote the book Nan’yō Jiji from his trip observations.Footnote 90

After taking the charge of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Enomoto appointed his loyal follower Andō Tarō as the head of the Emigration Bureau.Footnote 91 Andō’s Emigration Bureau only managed affairs of migration abroad and facilitated overseas expeditions to investigate migration destinations.Footnote 92 Though Enomoto and Andō managed to send a group of Japanese peasants to Mexico, this particular campaign soon failed due to poor planning and serious financial issues.Footnote 93 Nevertheless, it marked the beginning of Japanese migration to Latin America. In 1897, Mexico and Brazil were included in the Japanese Emigration Protection Law as migration destinations. This piece of legislation required Japanese subjects to name a guarantor when they submitted a passport application for the purpose of migration. Previously only the United States, Canada, Hawaiʻi, and Siam were deemed migration destinations.Footnote 94

Enomoto’s initiative also encouraged Japanese expansionists to carry out colonial projects of their own in the following years. Ensei’s July 1892 issue included a Japanese intellectual’s public letter to Enomoto Takeaki. Writing from San Francisco, the author praised Enomoto’s plan for Japanese expansion into Mexico as a glorious project that would bring permanent benefits to both the individuals involved and Japan itself for generations to come. He saluted Enomoto as the founding father of Japanese settler expansionism who jumpstarted the mission by founding the Republic of Ezo (Ezo Kyōwakoku).Footnote 95 While the Republic of Ezo was short-lived, the writer argued that if Enomoto transplanted his colonial project to Mexico, it would surely succeed.Footnote 96 Stimulated by both Enomoto’s initiative and widespread racism in the United States, the Japanese expansionists residing in the American West began to consider Latin America as a possible migration destination. Such ambitions led to their land acquisition campaigns in Baja California in the first two decades of the twentieth century.Footnote 97

The Peak of Shizoku Expansionism

In 1891, Tsuneya Seifuku, a government employee who had conducted an investigative trip to Mexico under Enomoto’s auspices, published a book titled On Overseas Colonial Migration (Kaigai Shokumin Ron). It gathered together the ideologies and proposals of shizoku expansion since Hokkaido migration in the 1870s.

In the first half of his book, Tsuneya urged the shizoku who were uncertain about their future in Japan to look beyond the archipelago.Footnote 98 He incorporated the ideas of racial competition, population growth, as well as economic development in his argument for shizoku expansion. Tsuneya described the world as one in which only the fittest races would survive; he emphasized the necessity for Japan to expand overseas and participate in the colonial competition against the Westerners. The Japanese, he further pointed out, were competent competitors: they had their own successful colonial conquests during the past few centuries, therefore they were the Westerners’ equal.Footnote 99 He followed this theme of racial competition with demographic comparisons between different countries, highlighting the fact that Japan had the highest population density among them all. To propel the nation forward, Tsuneya concluded, Japan should relocate a great number of people to both Hokkaido and other parts of the world.Footnote 100 Migration-based expansion, he further pointed out, was also necessary for Japan to keep its currently rapid rate of population growth and increase its national wealth.Footnote 101 He also reconciled the contemporary debates about the different migration models and the role that the government ought to play in them. Since expansionist migration was a crucial issue for the empire, Tsuneya argued, it should be conducted through collaboration between the government and the people. He was open to all manners of migration but believed that for the migrants – be they merchants, peasants, or temporary laborers – to remain valuable for the nation, they must all be protected by Japan’s naval power.Footnote 102 In the second half of the book, which examined the possible destinations of Japan’s expansionist migration, Tsuneya included both the South Seas and Latin America in his map.

If On Overseas Colonial Migration served as a theoretical summary of the previous agendas on shizoku expansion, the Colonial Association (Shokumin Kyōkai), established by Enomoto Takeaki in 1893, put the theory into practice.Footnote 103 The establishment of the Colonial Association as the first nationwide organization of overseas expansion marked the culmination of shizoku-centered expansionism in Meiji Japan. The association sponsored investigation trips and expeditions around the Pacific Rim. It also held public lectures and published an official journal named Reports of the Colonial Association (Shokumin Kyōkai Hōkokusho) to disseminate information about and ideas for overseas expansion. The association’s prospectus appeared in the journal’s inaugural issue, and it reiterated all the major ideas for overseas expansion in the previous years as summarized by Tsuneya.Footnote 104

The association’s choice of advising council and membership composition revealed partnerships between government officials and public intellectuals, between the promoters of Hokkaido migration and those in favor of overseas expansion.Footnote 105 The fact that leading figures from separate migration campaigns – Inoue Kakugorō, Shiga Shigetaka, Taguchi Ukichi, and Tsuneya Seifuku to name but a few – were all involved in the association illustrated the common foundation that these different schools of expansion shared. As direct ideological descendants of early Meiji colonial expansion in Hokkaido, they were all motivated by the desire to both reduce population pressure at home and increase Japan’s national power abroad. Shizoku, the group that posed the biggest threat to the new nation’s stability, was singled out as the ideal candidate for these projects. The processes of migration and settlement were expected to transform them into exemplary subjects of the empire.

Conclusion

This chapter has explained how shizoku migration to the American West paved the way for the genesis of Japanese expansion in the South Seas and Latin America in the last two decades of the nineteenth century. Shizoku expansionists’ encounter of white racism through Chinese exclusion in the United States allowed them to reinterpret the imperial competitions in the world as struggles between races. The exclusion of Chinese immigrants from the United States forced Japanese expansionists to temporarily move their gaze from North America to the South Seas and Latin America. In their imaginations, exporting the declassed samurai there to claim these still contested territories would allow the Japanese empire to claim its own colonial possessions amid the increasingly intensified global competition of race.

If white racism redirected Japanese expansion toward the Southern Hemisphere from outside, Malthusian expansionism continued to connect shizoku-centered political tension at home with colonial expansion abroad from the inside. Thinkers and participants in southward expansion had profound connections with shizoku migration in the recent past in Hokkaido, where the marriage between the discourse of overpopulation and migration-driven expansion originated. The formation of the Colonial Association and the campaigns of expansion it launched demonstrated the profound connections between the shizoku migration in Hokkaido, migration to the United States, and the ideas and activities of Japanese expansion in the South Seas and Latin America.

The Colonial Association continued to function and publish its journal until the beginning of the twentieth century. Yet the shizoku-based expansionist discourse, along with the generation of shizoku whose lives were fundamentally transformed by the turmoil of regime and policy changes, had faded from public consciousness by the mid-1890s. When the Japanese empire was on the cusp of a war with the Qing Empire that would redefine the geopolitics in East Asia, a new social discourse had already begun to emerge. It was rooted in the rise of urban decay and rural poverty, results of Japan’s rapid industrialization and urbanization. Ideologues of expansion, joined by social reformers, began to propose migration abroad, particular to the United States, as a solution to rescue the common poor from their misery at home. The shizoku generation was giving way to the rise of unprivileged commoners in Japanese society; Japan’s migration-driven expansion thus entered a new stage. The following chapter examines the commoner-centered Japanese migration to the United States that took place from the mid-1890s to 1907.