Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 Public women: the Restoration to the death of Aphra Behn, 1660–1689

- 2 Partisans of virtue and religion, 1689–1702

- 3 Politics, gallantry, and ladies in the reign of Queen Anne, 1702–1714

- 4 Battle joined, 1715–1737

- 5 Women as members of the literary family, 1737–1756

- 6 Bluestockings and sentimental writers, 1756–1776

- 7 Romance and comedy, 1777–1789

- Notes

- Recommended modern editions

- Select bibliography

- Index

- References

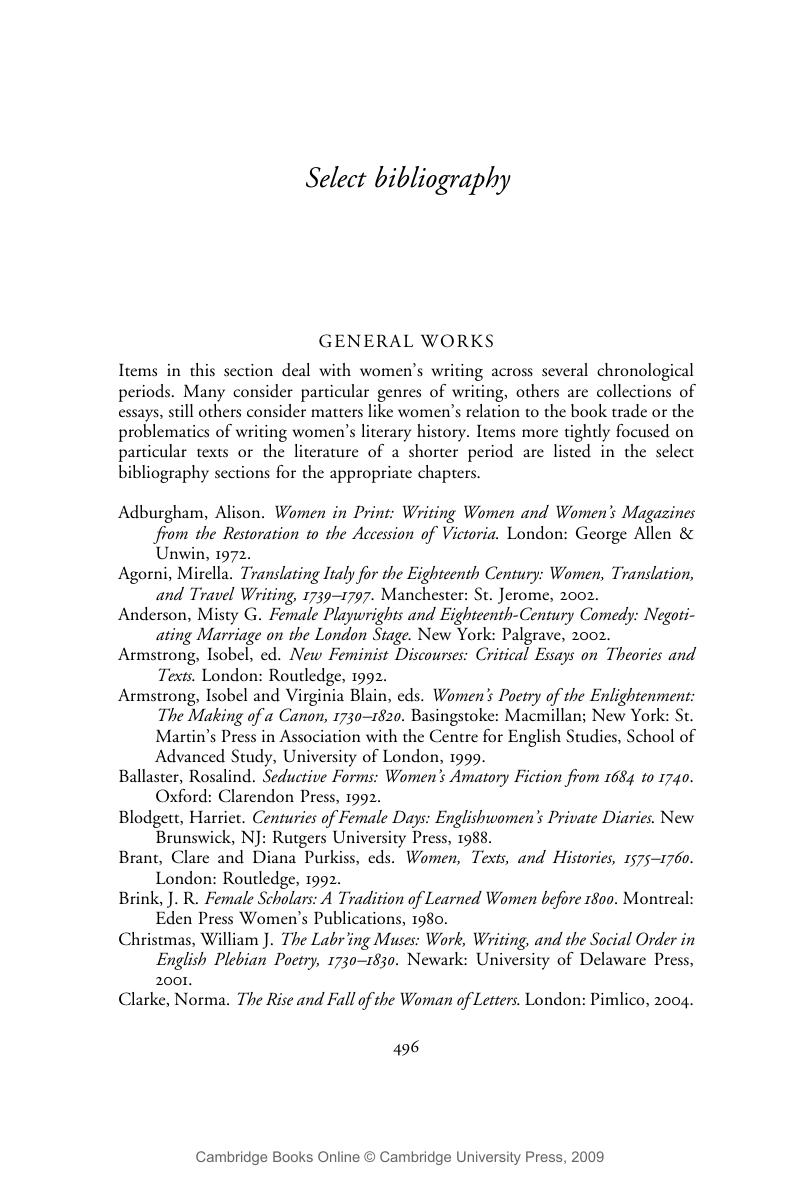

Select bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 06 November 2009

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 Public women: the Restoration to the death of Aphra Behn, 1660–1689

- 2 Partisans of virtue and religion, 1689–1702

- 3 Politics, gallantry, and ladies in the reign of Queen Anne, 1702–1714

- 4 Battle joined, 1715–1737

- 5 Women as members of the literary family, 1737–1756

- 6 Bluestockings and sentimental writers, 1756–1776

- 7 Romance and comedy, 1777–1789

- Notes

- Recommended modern editions

- Select bibliography

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- A Literary History of Women's Writing in Britain, 1660–1789 , pp. 496 - 512Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2006