Book contents

- Interaction, Feedback and Task Research in Second Language Learning

- Interaction, Feedback and Task Research in Second Language Learning

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures

- Tables

- Preface

- Chapter One Theory and Approaches in Research into Interaction, Corrective Feedback, and Tasks in L2 Learning

- Chapter Two Designing Studies of the Roles of Interaction, Feedback, and Tasks in Second Language Learning

- Chapter Three Investigating Individual Differences in Interaction, Feedback, and Task Studies: Aptitude, Working Memory, Cognitive Creativity, and New Findings in L2 Learning

- Chapter Four Collecting Introspective Data in Interaction, Feedback, and Task Research

- Chapter Five Creating and Using Surveys, Interviews, and Mixed Methods for Research into Interaction, Corrective Feedback, Tasks, and L2 Learning

- Chapter Six Doing Meta-Analytic and Synthetic Research on Interaction, Feedback, Tasks, and L2 Learning

- Chapter Seven Investigating Interaction, Feedback, Tasks, and L2 Learning in Instructional Settings

- Chapter Eight Choosing and Using Eye-Tracking, Imaging, and Prompted Production Measures to Investigate Interaction, Feedback, and Tasks in L2 Learning

- Chapter Nine Working with Data in Interaction, Feedback, and Task Research

- Chapter Ten Common Problems, Pitfalls, and How to Address Them in Research on Interaction, Corrective Feedback, and Tasks in L2 Learning

- Glossary

- References

- Index

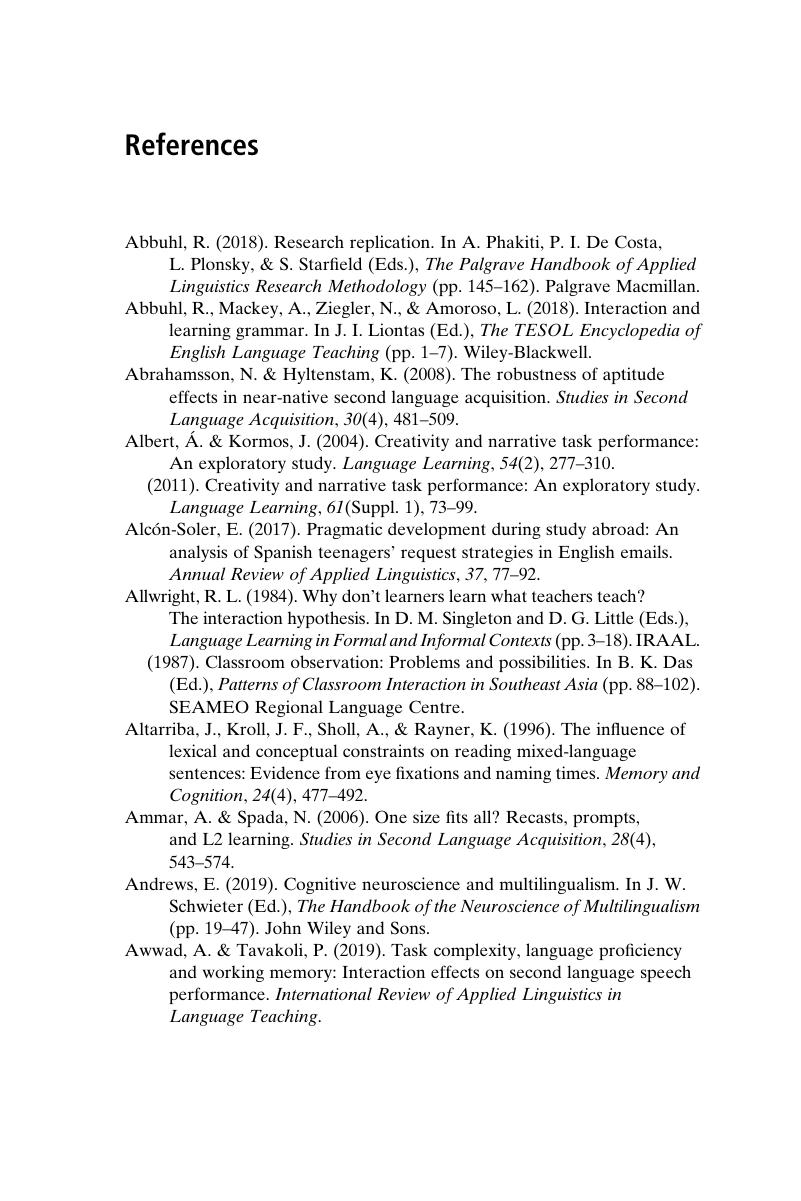

- References

References

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 03 August 2020

- Interaction, Feedback and Task Research in Second Language Learning

- Interaction, Feedback and Task Research in Second Language Learning

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures

- Tables

- Preface

- Chapter One Theory and Approaches in Research into Interaction, Corrective Feedback, and Tasks in L2 Learning

- Chapter Two Designing Studies of the Roles of Interaction, Feedback, and Tasks in Second Language Learning

- Chapter Three Investigating Individual Differences in Interaction, Feedback, and Task Studies: Aptitude, Working Memory, Cognitive Creativity, and New Findings in L2 Learning

- Chapter Four Collecting Introspective Data in Interaction, Feedback, and Task Research

- Chapter Five Creating and Using Surveys, Interviews, and Mixed Methods for Research into Interaction, Corrective Feedback, Tasks, and L2 Learning

- Chapter Six Doing Meta-Analytic and Synthetic Research on Interaction, Feedback, Tasks, and L2 Learning

- Chapter Seven Investigating Interaction, Feedback, Tasks, and L2 Learning in Instructional Settings

- Chapter Eight Choosing and Using Eye-Tracking, Imaging, and Prompted Production Measures to Investigate Interaction, Feedback, and Tasks in L2 Learning

- Chapter Nine Working with Data in Interaction, Feedback, and Task Research

- Chapter Ten Common Problems, Pitfalls, and How to Address Them in Research on Interaction, Corrective Feedback, and Tasks in L2 Learning

- Glossary

- References

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Interaction, Feedback and Task Research in Second Language LearningMethods and Design, pp. 214 - 239Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2020