Except in the processes of butchering, outcastes could not handle foods to be eaten by ordinary people.

Introduction

Both long-standing and more recent engagements with zooarchaeology often pivot between two distinct polarities: the economic and the social (Marciniak Reference Marciniak2005; Russell Reference Russell2012; Arbuckle & McCarty Reference Arbuckle and McCarty2014; Sykes Reference Sykes2014). Not surprisingly, the ‘social turn’ has often focused on topics of shared historic interest, namely, the consumption of animals and their role in ritual and religious expression (Russell Reference Russell2012: 91; Sykes Reference Sykes2014: 114–32). Meat has long been an important topic (e.g., ‘Meat beyond diet’, in Russell Reference Russell2012: 358–94) and builds on a wider and more established body of anthropological literature. Excellent scholarship on the role of food and meat as social capital exists at least since the work of Spencer (1898: religion and military influence) and Veblen (1910: conspicuous consumption). Anthropological enquiry of the 1960s to 1980s further reinforced alimentation as central to human thought and practice, with important theoretical developments made by Lévi-Strauss (Reference Lévi-Strauss1966, Reference Lévi-Strauss1970, Reference Lévi-Strauss1978), Douglas (Reference Douglas1970, Reference Douglas1975), Barthes (Reference Barthes, Forster and Forster1975), Goody (Reference Goody1982), and Harris (Reference Harris1985). These authors emphasise the ways in which cuisine, dining, and social stratification can be viewed through the medium of food. The role of meat protein in human evolution (Aiello & Wheeler Reference Aeillo and Wheeler1995; Stanford Reference Stanford1999; Navarrete et al. Reference Navarrete, van Schaik and Isler2011), alongside issues surrounding the ethics of consuming animals (Marcus Reference Marcus2005) and the engendered nature of meat representation (Adams Reference Adams1990; Ruby & Heine Reference Ruby and Heine2011), illustrate the diverse relationships that we have with animal bodies and their flesh. Among these varied perspectives, Fiddes’s Meat: A Natural Symbol (Reference Fiddes1991) stands out as a seminal text, arguing for recognition of the role meat has played in a range of social settings.

Mengzi wrote: ‘a taste for meat is at a world level the most commonly shared penchant’ (Sabban Reference Sabban1993: 81). Meat consumption is arguably the most highly charged, widely debated, and heavily moralised food topic, occupying a seminal place within studies of food. However, the trend to emphasize the outcome – flesh, or meat – has tended to draw attention away from how we arrive at the commodity. As I illustrate in this chapter, butchery is also ‘a highly charged and heavily moralized food topic’.

Anthropological research focused specifically on butchery and butchering takes wide-ranging forms. For example, ethnographic studies have explored the relationship between the butcher, the animal, and the location of carcass processing (Mooketsi Reference Mooketsi2001), as a way of connecting butchery to wider social drivers. The varied interconnections between animal processing, the animal’s flesh, and the construction of taboos have also been an area of keen interest for ethnographers (Ross et al. Reference Ross1978; Forth Reference Forth2007; Luzar et al. Reference Luzar, Silvius and Fragoso2012). This broad category, not necessarily anthropological in methods but in research focus, also includes contemporary studies of the history of the industry (Watts Reference Watts2006; Lee Reference Lee2008; Fairlie Reference Fairlie2010; Pacyga Reference Pacyga2015) and those who work in it (Fogel Reference Fogel1970; Pilcher Reference Pilcher2006). Of the latter category, perhaps the most influential work of the time was a fictitious narrative called The Jungle, by Upton Sinclair (serialised in 1905, published in 1906), which highlighted the working conditions of the then modern industry and led to sweeping reforms in the United States.

I have deliberately brought together a wide range of perspectives to emphasise the diversity of relationships that exist and revolve around butchery. In all the above cases, whether directly or indirectly, butchering is central. The above represents a top-down interpretation of carcass processing, considered from the perspective of the place of meat in society. The complementary viewpoint from archaeological remains will not be as clear. It is easier to see how cut marks can be indicative of specific sharing practices in non-industrialised cultures, but perhaps harder to note how butchery processes may provide a lens on industrialisation itself or those involved in the trade. Such ideas offer testable hypotheses and raise the bar in terms of the type of questions archaeologists investigate. As Russell (Reference Russell2012: 3) suggests, moving beyond ‘protein and calories’ allows us to view a more complete repertoire of factors that influence how we interact with non-human animals.

Thus, in contrast to the social equality that actor–network theory (ANT) presupposes, an important aspect of butchery revolves around the power and influence of social attitudes toward aspects of the craft and those involved in it. Meat is featured within a range of settings, from civic identity (Billington Reference Billington1990; Seetah Reference Seetah, Pluskowski, Kunst, Kucera, Bietak and Hein2010) to negativity associated with working closely with animal bodies, their waste, and death (Charsley Reference Charsley1996). It serves as a dominant means of social differentiation (Groemer Reference Groemer2001). However, in none of the examples described so far are we actually relying on cut marks to deepen our understanding of the role of meat. An excellent illustration of this point is Mooketsi’s (Reference Mooketsi2001) research in Botswana, whose analysis evaluates the role of butchery and the butcher, but includes no assessment of cut marks.

Focusing on non-mechanised settings and emphasising ‘social practice’, the following explores how cross-cultural perceptions of ‘self’ and ‘other’ are codified and expressed on the basis of interactions with animal bodies. Applying the principles of analogy, ethnographic enquiry, and ethnoarchaeology, the discussion positions butchery within the larger socioeconomic context, spotlighting an aspect that is central to how the craft developed: the relationship between those who work as butchers and the society in which they live. This offers zooarchaeologists a way to connect butchery as ‘sociotechnological practice’ to society and to situate the practitioners involved in various crafts. This stance also provides a bridge between social and economic sides of zooarchaeology and resonates with developments in chaîne opératoire that are aimed at uniting practice and the practitioner.

This chapter engages with ideas drawn from social studies. In this regard, ‘status’ relates to a socially defined position in society, whether small scale or large; ‘social differentiation’ describes the process by which different statuses develop in any given society; and ‘social stratification’ refers to relatively fixed, hierarchical arrangements in society by which groups have varying access to social and economic capital. In addition, I also borrow from social studies to distinguish between caste and class systems, the former denoting that an individual’s standing in a stratified system is ascribed, while the latter emphasises that a person’s place within their stratification can change according to their achievements (Saunders Reference Saunders2006: 1–27).

Craft, Marginalised Groups, and Archaeology

The study of humans and animals in the past could benefit from adopting tried and tested approaches developed for other material sciences in archaeology. Studies of metal (Lahiri Reference Lahiri1995; Derevenski Reference Derevenski2000), ceramics (Jones Reference Jones2001; Arthur Reference Arthur2014a), and lithic implements (Weedman Reference Weedman2006) have all shown that ideology and cosmology are critical drivers of production, assembly, use, and discard of objects: ‘The ideological underpinnings of metalcraft and the perception of metalcraftpersons provide the context and justification for understanding some of their practices’ (Lahiri Reference Lahiri1995: 116). In numerous cases, ethnoarchaeology has helped to reveal ideology in ways that can then be directly applied to the archaeological context (Arthur et al. Reference Arthur, Arthur, Curtis, Lakew and Lesur-Gebremarium2009). Weedman, for example, points to how an ideology of purity drives segregation of certain artisanal groups who form part of Gamo society, in Ethiopia (Reference Weedman2006). A number of features seem to illustrate salience across geographic, chronological, and cultural boundaries, which may have genuine significance for understanding ‘craft’ in a more complete way. Indeed, approached in this way, situating craft becomes an essential feature of human evolution, expression of social norms, and economic development. Studies have shown how relationships within discrete ‘craft groups’ influence the transmission of practice. In India, for example, enskilment is expressed along caste or caste-like lines; ‘occupational speciality is learned and shared within endogamous groups which often have distinctive names and sometimes live in circumscribed areas’ (David & Kramer Reference David and Kramer2001: 308). This is equally the case for relationships between craft groups. In cases where ideology drives segregation of certain crafts – seen as distasteful, unclean, or impure – which are then collected into one location on the periphery of a settlement, this can lead to between-group marriage, with attendant ramifications for learning, acquiring, or refining skills (Sterner & David Reference Sterner and David1991).

Zooarchaeologists recognise the importance of ideology as a driving force in the creation of bone assemblages. However, these have generally been restricted to specific cases, particularly as they relate to religious and ritual practice (Greenfield & Bouchnik Reference Greenfield, Bouchnick, Amundsen-Meyer, Engel and Pickering2011: 106–10). The potential benefits of adopting the types of detailed ethnoarchaeological studies that have gained attention in the study of pottery and lithics are impressive, particularly in situating the human half of the human–animal relationship.

Carcass to Meat – A Hard Act to Swallow?

The social and ethnographic contexts surrounding the practice of butchery reinforce the notion that craft is embedded within cultural milieus. In the discussion that follows, the lens falls firmly on the human agent, rather than animal bone or cut marks. For some societies, the corporeal animal carcass is seen to retain qualities that are considered base, attributes that the spiritual human should avoid. The examples are drawn from in-depth contemporary case studies that discuss marginalised groups from a range of culture contexts. Drawing on and generalising from this extensive literature, I examine how relations with meat, slaughter, animal bodies, and body-part processing have formed the basis for negative attitudes toward those individuals involved in these crafts. In the interests of further expanding the picture, I also draw on cases where those involved in animal slaughter and processing derive from the religious elite or economically privileged portions of society. A brief survey of post-medieval to contemporary examples drawn from Europe, in particular Britain, and the United States is presented to contextualise the ethnographic and historic case studies with modern industrialised examples. These cases illustrate some of the ways that the craft of butchery changed, once systems were in place to deal with those aspects of butchery that caused greatest nuisance. This final category is grounded more in the development of capital and less on belief, although religion and ideas of sanitation and cleanliness were still important drivers.

Although this is not a universal, it is often the case that societal attitudes toward those involved in animal processing can be vehemently negative. Religious principles and moralised understandings of cleanliness serve to create and promulgate identities that define individuals, and even ethnicities, in terms of their associations with butchery, within larger contexts like regions or nations. Positive attitudes can be equally socially relevant in some settings and likely rest on the fact that the butchers were valued because of their skill and knowledge, as well as for the economic capital that their enterprise made possible. In some instances, this also extended to increased social value (Billington Reference Billington1990). I focus more of my attention on examining and understanding negative attitudes, as these have harmful outcomes for the people involved. Further, the consequences of these negative attitudes have tended to concretise practical tasks and material objects within and around the marginalised groups’ environment, particularly through endogamy, and this has particular relevance for archaeologists.

A number of characteristics appear to drive negative attitudes to carcass processors. For many, meat consumption is associated with vitality and good health (Brantz Reference Brantz2005). In contrast, vegetarianism, veganism, and modern concerns about the implications of excess meat on human and environmental health – to name a few examples – all point to the ways in which individuals and societies wrestle with the act of consuming flesh (Rozin et al. Reference 248Rozin, Markwith and Stoess1997; Ruby & Heine Reference Ruby and Heine2011; De Backer & Hudders Reference De Backer and Hudders2015). Whether viewed from the perspective of individual or societal unease, one facet of consumption has historically been of particular concern: slaughter. It has been suggested that meat consumption decreases as societies advance technologically, while sensitivities toward the act of slaughter itself increase (Ellen Reference Ellen and Ingold1994: 203). This is far from universal. Indeed, certain cultures consider the suffering of the animal to be an essential aspect of ritual sacrifice preceding consumption. For the Masa Guisey of Cameroon, for instance, the offering of a chicken involves a slow death, the bird plucked and singed while alive (de Garine Reference de Garine2004).

To take another example, for many practicing Buddhists and Hindus, it is precisely this suffering that underpins their cultural attitude against the taking of life for consumption. Similarly, for Christians, Jews, and Muslims, religion plays an important role in shaping attitudes toward meat eating or those who undertook slaughter. However, in each case important nuances exist, particularly in accordance with interpretations of religious texts (Bouchnik Reference Bouchnik, Marom, Yeshuran, Weissbrod and Bar-Oz2016: 306). For Judaism and Islam, the act of slaughter was an integral aspect of religious practice (Greenfield & Bouchnik Reference Greenfield, Bouchnick, Amundsen-Meyer, Engel and Pickering2011: 107). In contrast, during the Middle Ages in Europe, as part of a more general emphasis on abstinence and material paucity to avoid the sin of gluttony, certain orders of monks refrained from eating meat. The situation is further complicated due to religious ideology. In medieval Latin Christendom, meat could be associated with moral pollution as it was considered to promote sexual appetite. However, at the same time, many religious groups, particularly high-ranking clerics and abbots, regularly consumed meat (Ervynck Reference Ervynck, O’Day, Van Neer and Ervynck2004: 216–21). The view of animals also needs to be situated: fauna walked on all four feet and were closer to the earth, and therefore base. Worse still were snakes, which crawl and were the ‘adulterer’ (Crane Reference Crane2013: 100). Indeed, by the Carolingian period, the rule of Saint Benedict was widely adopted in Western Europe, resulting in the prohibition of meat from quadrupeds for monks in good health (Schmitz Reference Schmitz1945). Ultimately, this may help explain the subsequent dependence on fish (Ervynck Reference Ervynck, O’Day, Van Neer and Ervynck2004: 219).

Faith systems from Asia illustrate a number of examples of ‘sins by association’, discussed in the case studies presented below. Becoming morally polluted, as per the Christian example from the Middle Ages, is reinforced by a range of Asian examples that emphasise physical pollution, as a consequence of working with animal bodies and their blood and waste. This illustrates the complexity of the situation. In numerous cases it is not meat that is the problem, nor its consumption, but rather the specific interaction that the human has with the beast: killing. Slaughter, and preparing a ‘corpse’ through evisceration, exsanguination, and skinning, incorporates a different set of acts than preparing ‘meat’ for consumption. More recently, these ‘wet’ acts, in societies where butchery and carcass preparation have become institutionalised (Lee Reference Lee2008: 4), have been removed from public view. The flesh is transformed into meat behind closed doors (Vialles Reference Vialles1994: 5). The preparation of meat for consumption is clearly an act of butchery, but one associated with food: through cuisine, meat is prepared to be eaten.

Economy also plays an intriguing role. It is revealing that in many cases considerable wealth was involved. Monastic communities invested large amounts of capital into fish, fowl, and game, all examples of flesh that they could consume (Murray et al. Reference Murray, McCormick and Plunkett2004). Butcher castes in Asian and African contexts monopolised the processing of animals and could become very wealthy. However, in these latter cases, the financial capital could not erase the perceived notions of defilement nor permit those involved in the profession to transition to a better social class.

Finally, while the following accounts are drawn from contemporary or recent historic accounts, we should be alerted to the likelihood that this type of social stratification might reveal itself to have been far more prevalent in the archaeological past. Two accounts from the Canary Islands, recorded during early contact between pre-Hispanic peoples and Castilians, provide tantalising food for thought for historical zooarchaeologists:

The job of butcher was perceived as vile and crude, and was performed by the lowest man; and he was so disgusting that he was not allowed to touch anything, to him was handed a wood stick to point at the things he wanted. He was not admissible inside the houses, or to mingle with people, but only with other colleagues of his profession; and as a reward for his submission, he was given the things he needed. And none was allowed to kill any animal, unless in the places arranged by the butcher, and in these houses youths, women and children were not admissible.

[T]he worst damage they could enact on the Spaniards captured by them (the indigenous peoples), was to scalp them and make them slaughter animals for meat, and to cook it, and to roast it.

These fascinating reports speak of ‘untouchability’ within a wholly unrelated context to that seen in India or other modern analogues (Price Reference Price, De Vos and Wagatsuma1966: 39; Amos Reference Amos2011: 29–32). They also exemplify a phenomenon that is repeated in many of the cases that I will present: carcass processing is defined culturally as among the basest and most menial tasks that an individual can perform. Finally, another remarkable similarity is that a deeply ingrained hierarchy seems to be a common feature of the societies outlined, which was the case for the agricultural, pre-Hispanic peoples of the Canary Islands (Morales et al. Reference Morales, Rodríguez, Alberto, Machado and Criado2009).

Case Studies in Social Differentiation

Of the three monotheistic religions, none would prohibit a butcher from entering a place of worship. Indeed, for Islam, Judaism, and Christianity, a case could be made for the fact that meat processors and butchers enjoyed a relatively well-regarded status, whether due to economic factors or because they performed a task that had its roots in religious text. However, in India, Japan, and Korea, for example, religious and societal ideals created a complex system of separation for those whose trade resulted in an association with animals and animal bodies. In particular, butchering of animals appears as an almost universal mechanism used to designate outcaste status (de Vos & Wagatsuma Reference De Vos and Wagatsuma1966: 7). In all these cases, a social hierarchy based on heredity, in combination with a religious ideology based on a tenet of cyclical rebirth, led to the establishment of systems of untouchables and outcastes that extend to the present day (Groemer Reference Groemer2001; McClain Reference McClain2002: 100). The following survey commences with India, partly as it has the largest and oldest ‘outcaste’ population of any contemporary society, as well as one of the most complex (Mendelsohn & Vicziany Reference Mendelsohn and Vicziany1998: 1–6; Jodhka Reference Jodhka2012: 1–33; see also Appadurai Reference Appadurai1988). In India, the caste system and the plight of the untouchables has been one that has received a great deal of public attention, particularly since the time of Gandhi (Adams Reference Adams2010; Das Reference Das2010).

India

The relationship between abstinence from meat eating and Hinduism is well known and complex (Staples Reference Staples2008) and, as one might imagine, has ramifications for those who are involved in carcass processing. One way to achieve virtue and promote a positive karma for Hindus is to abstain from eating meat. However, equating modern vegetarianism with Buddhist and Hindu traditions is not an accurate comparison (Masri Reference Masri1989: 49). Neither Buddhists nor Hindus are against the eating of meat per se (although this point is contested, see Page Reference Page1999: 122); it is the sanctity of life that prompts a vegetarian diet in these groups. Both faiths permit the eating of meat that has not been killed expressly for the purposes of the individual’s consumption (Hopkins Reference Hopkins1906; Chakravarti Reference Chakravarti1979; Masri Reference Masri1989: 49). Furthermore, within the Hindu caste system, a person of the warrior caste would be considered to be acting within the remits of their nature to eat meat, for example, to improve physical conditioning (Khare Reference Khare1966).

India’s endogamous system of social hierarchy is based on various attributes that include vocation, religious belief, and linguistics. The Jāti (a group of communities) is divided into four main castes to which all individuals belong. Each Jāti is associated with a traditional trade, job, or tribe. Those of the lowest Jāti were invariably involved in professions that were considered menial, such as blacksmiths and weavers (Natrajan Reference Natrajan2012: 29–30). Within this social stratification exists a level that is beneath the lowest of castes: the untouchables.

Caste differentiation is socially sanctioned and condoned to the point that those involved in the animal trades are regarded as inhuman (a theme that recurs in both Japan and Korea). In part, this was based on fatalism (Elder Reference Elder1966). The individual must have been wicked in a previous life; it was their karma. Those involved in animal trades were considered base, untouchable because of their profession and both physically and ritually polluted (Passin Reference Passin1955, Reference Passin1957; Mendelsohn & Vicziany Reference Mendelsohn and Vicziany1998: 7). There is a difference between the notions of caste and ‘outcaste’ (which is a better descriptor for the Japanese and Korean examples) and untouchability. Though untouchables worked in a range of professions, including sweeping and laundering, those involved in animal slaughter and processing were considered tainted because they performed a task that was defiling (Price Reference Price, De Vos and Wagatsuma1966: 39). To illustrate this, Brahmins (the highest caste composed of priests) who killed animals for consumption were considered inferior to other Brahmins who did not (Dumont Reference Dumont1980: 358). It is the interaction with animals, and specifically the act of slaughter, which underpins the idea of moral pollution. Those who repetitively performed such tasks were not able to remove the taint that killing left on them and they deserved to be both reviled and ostracised. Although they might attain wealth and prosperity, relative to their station (Siddiqi Reference Siddiqi2001), they were never able to remove the desecration of their actions.

Social differentiation based on caste in India is expressed in a number of physical ways; in the worst cases these are violent (Shah Reference Shah2006: 97; Natrajan Reference Natrajan2012: 11 and 170n3). Lower castes could be precluded from entering temples; they could not associate with those of a higher caste nor take meals with them (Mines Reference Mines2009: 1). Their social positions become fixed from one generation to the next due to endogamic marriage. For the untouchables, as the name implies, no physical contact could take place with members of a higher caste (Charsley Reference Charsley1996). For those untouchables who dealt with animals – the slaughterers, butchers, tanners, and leatherworkers – the act of killing animals and working with their body parts was seen as penance. Thus, there was no compunction in treating them with disdain. Their release from this particular status would come with death, and, provided they were virtuous in their present lives, their rebirth would be more favourable.

Japan

As in India, similar cultural and religious ideologies combined to create Japan’s own outcastes, the Eta (meaning ‘defilement abundant’). During the Tokugawa Period (1603–1868) this group’s ostracism effectively became codified in law and practice (De Vos & Wagatsuma Reference De Vos and Wagatsuma1966; Groemer Reference Groemer2001; see Amos Reference Amos2011 for a recent and important work on the Burakumin). The situation in Japan was different to India in that two separate religious ideologies, analogous but fundamentally distinct coalesced to influence the creation of social outcastes (De Vos & Wagatsuma Reference De Vos and Wagatsuma1966: 3). An underlying tenet of Shintō is avoidance of impurity (McClain Reference McClain2002: 100). While Christianity views cleanliness as next to godliness, in Shintō cleanliness is godliness (Passin Reference Passin1955). In effect, those who worked with animals were not in a position to be able to attain purity; they were irrevocably impure, dirty, and corrupt. With the arrival of Buddhism and an ethic that all life was sacred (Donoghue Reference Donoghue1957; McCormack Reference McCormack2013: 39), those involved in animal trades, especially those who had to carry out the physical act of slaughter and the letting of blood, were even more reviled and considered to be polluted. Eta were composed of a range of professions. Thus, leatherworkers, tanners, and butchers were grouped with unlicensed prostitutes. This indirectly illustrates the social group that those in the animal trades were identified with. Another group of outcastes, termed Hinin (non-human), included professions considered unsavoury, such as monkey trainers and actors. As with the untouchables of India, the condition was considered hereditary, but only for the Eta; the Hinin were outcastes because of the professions they found themselves in due to poverty or other reasons (Passin Reference Passin1955). In an interesting parallel with numerous European examples, Eta involved in animal trades were called on to be executioners (Groemer Reference Groemer2001).

The clear division between the treatment of Eta and Hinin and of ‘normal’ people exemplifies the attitude to this outcaste group. Eta were historically excluded from censuses or, if recorded, were tabulated separately from ‘people’. Their villages were not recorded on maps or the maps themselves were abridged to eliminate the location of their dwellings. These attitudes were legally as well as socially sanctioned. In 1859 a magistrate was asked to rule on the case of a non-Eta killing an Eta. He decreed that an Eta was one-seventh of a normal person, and therefore the non-Eta would have to kill six more Eta before he could be punished. The descriptive terms Eta and Hinin are themselves highly offensive, equivalent to racial slurs. This has more recently resulted in the use of terms such as Burakumin (community people), which is considered less offensive.1 The mark of the beast was firmly reinforced by a variety of derogatory animal associations. Eta would be counted with the same classifier as used for animals (Hiki: 匹). The common insult for Eta was to hold four fingers in the air or refer to an Eta as ‘four’. This was intended to reinforce the association between animals and Eta, suggesting the four legs of an animal, or that the Eta had only four fingers, one less than normal people (Passin Reference Passin1955). These attitudes are so pervasive that even in the more recent past, Eta have considered themselves to be base, identifying strongly both with their activity and with animals. During interviews conducted with members of the Burakumin, when asked if they are the same as other, non-Eta, people, the response was that they were not: ‘We kill animals. We are dirty, and some people think we are not human.’ When asked why other people are better, ‘They do not kill animals’ was the response (Donoghue Reference Donoghue1957: 1015).

Korea

The Korean outcaste system, established during the Koryo Period (AD 918–1319) reflected many similarities to those seen in Japan. Like Japan, the incumbent belief system, in this case Confucianism, upheld ideals of upper and lower orders and served as a basis for social differentiation. With the arrival of Buddhism and the doctrine of the sanctity of life, those ‘lower orders’ of people involved in animal trades, who could never truly attain virtue according to Confucianism, became outcastes (Passin Reference Passin1957; Neary Reference Neary1987). As in Japan, two groups of endogamous outcastes were created: the Paekchŏng (or Baekjeong), who were butchers and analogous with the Eta, and the Chianin (or Jaein), incorporating the same vocational groups as the Hinin.

More so than the Indian and Japanese examples, the Paekchŏng were charged with all aspects of animal processing. They were the leatherworkers, tanners, and of course butchers (Kim Reference Kim2013: 15). They were also dogcatchers and responsible for the removal of animal carcasses. Of the outcastes mentioned, they were arguably the group most closely associated and defined by the subject of their trade. Again, the theme of moral inadequacy was exemplified in their role as executioners. Although the creation of this outcaste group effectively permitted the Paekchŏng to monopolise certain trades, this did little to compensate for the degree of social ostracism. The measures to delineate these outcastes were extreme. They were expected to show acute servility, bowing to all those from upper classes, including children. Their isolation from society was promoted in a range of forms. They were not permitted to wear silk, nor the top hats that all married persons wore, and could not roof their houses with tile. Thus, the group could be easily identified through their clothes and homesteads. Furthermore, they had to bury their dead in segregated plots and were not permitted to use funeral carts (Passin Reference Passin1955).

Tibet and China

Tibet shares similarities with India, Japan, and Korea. In Tibet, the subjects of marginalisation are the Ragyappa (or Rogyapa), who are responsible for slaughtering and the removal of animal carcasses, as well as preparing human corpses for sky burial (Gould Reference Gould1960). However, China has no such social outcastes based on animal trades, although outcastes exist as a consequence of other social attributes (Hansson Reference Hansson1996). The underlying difference is that China has a system of hierarchy based on virtue (Gould Reference Gould1960) rather than heredity, which can be considered a class, rather than caste, system.

African Examples

African examples of endogamic caste systems, sanctioned and based on occupation (Weedman Reference Weedman2006; Arthur Reference Arthur2008, Reference Arthur2014b), illustrate salience in many regions of the world, reinforcing multiple cases of social causation. Indeed, though castes have been considered a pan-Indian phenomenon, the similarities are remarkable, with all criteria of true caste met save the influence of Hinduism (Pankhurst Reference Pankhurst1999).2 Ethiopia has been a particularly noteworthy case (Halpike Reference Hallpike1968; Todd Reference Todd1978).

Among the indigenous Manga people of the Central African Republic are the Hausa, who entered the region following European colonialism, circa 1900. Although the Hausa as a group are not defined as ‘butchers’, within their population is a subgroup of professional butchers. This subcaste incurs both inter- and intragroup prejudice as a consequence of their association with animals, the act of killing, and the letting of blood. This is despite the fact that their profession allows them to attain considerable wealth. Their base nature is considered adequately strong that they have no obligation to partake in religious ceremony or hadj, and the wives of Hausa butchers are not secluded in walled enclosures as are the women of the Manga, which is an expectation under Islamic edict (Horowitz Reference Horowitz1974).

The polluting effect of slaughter forms the driver for other butcher castes. In Senegal, the ‘griot’ serve as butchers among the Wolof and Serer peoples. In northern Cameroon a sacrificer, who formerly would have been a slave, performs the act of slaughter in lieu of the religious chiefs who are prohibited from killing or handling meat (de Garine Reference de Garine2004).

In Ethiopia, the role of the Fuga in Gurage society highlights the issue of hygiene and cleanliness that often underpins cultural attitudes to butchery. The Fuga, a somewhat generic term for indigenous groups in the region, are considered to be primitive hunters that were subjugated during the historic past. In this case, the Fuga were first conquered several centuries ago by the Sidāmo, and subsequently by the Gurage, and now live as part of the Western Gurage Tribes. Craft specialisation typifies their role in Gurage society. In particular, their role as tanners, Gezhä, is a key profession, and the skills of this craft are passed on from generation to generation. The Gurage consider the specific roles taken up by the Fuga to be vile, and this expresses itself through a disdain for any physical contact. The fear of contamination is so severe that Fuga can only enter the house of a Gurage if invited, following which the homestead is ritualistically cleansed (Shack Reference Shack1964). The Fuga are also required to practice endogamy.

Projecting the Character of ‘the Butcher’

In contrast to the cases outlined above, a brief survey of Judaic, Islamic, medieval, and modern Western perspectives provides counterpoints to the types of negative associations that have been attributed to those involved in carcass processing. In some cases, the same roles and practices are used as a powerful means of self-identification and nationhood. It should be made clear that these examples do not mimic the cases already discussed; the cultural context is wholly different. Rather, the following illustrates the diversity of the lived experience. Here, positive associations are discussed as they relate, once again, to religious ideology but also to developing modernity. It should also be noted that negativity is not absent in these cases. However, in addition to negativity being predicated on society’s view of those who butcher, and attendant associations with death and bodily waste, there were also economic drivers, such as the fear that butchers deliberately sold diseased meat for general consumption. The point to note is that these adverse attitudes did not result in the level of social ostracism observed in the African and Asian cases.

In Jewish and Muslim traditions not only must the animal be consecrated prior to slaughter, but also only specified men, often a rabbi in the Jewish faith, are permitted to carry out the act of killing (Masri Reference Masri1989: 113; Cohn-Sherbok Reference Cohn-Sherbok, Waldau and Patton2006: 86). Slaughter, if performed according to correct practice, is not seen as defiling. In fact, Judaic and Islamic practices demonstrate the polar opposite of the Asian perspective. Here the groups identify themselves by the specific way in which they kill and process animals. The practices associated with keeping kosher are thus used to preserve group identity (Feeley-Harnik Reference Feeley-Harnik1995; Brumberg-Kraus Reference Brumberg-Kraus1999; Buckser Reference Buckser1999). However, where these religious groups form a minority within other communities, the techniques and practices of slaughter have drawn attention, emphasising the differences between groups and reinforcing the ideology of ‘the other’. Attitudes toward shechita in Europe and America have highlighted the association between anti-Semitism and the anti-shechita movement, veiled behind the rhetoric of prevention of animal cruelty (Lewin et al. Reference Lewin, Munk and Berman1946: 21; Judd Reference Judd2007). Similarly, in parts of Europe and France in particular, the Muslim fête du mouton has received particular attention as a consequence of the overt nature of sacrifice, and slaughter, within urban enclaves (Brisebarre Reference Brisebarre1998).

Capital growth, modernity, and industrialization also influenced the way those involved in carcass processing were viewed. Using Britain as an example, individuals working in the animal trades and associated with the various guilds were part of powerful institutions. Members of the Butchers’ Guild, which attained Royal Charter in 1605 (Jones Reference Jones1976: 33), enjoyed a large degree of public goodwill and were integral to particular festive occasions (Billington Reference Billington1990). They were also important to the economy of major urban enclaves (Watts Reference Watts2006) and provided a service that received the attention of nobility and even royalty (Jones Reference Jones1976: 181). On a more fundamental level, butchers themselves were valued, and this can be seen in the fact that their shops were often located on the high street. Indeed, by the 1600s, at a time when many trades were restricted to a single street, which could quite literally be a back alley, butchers in London had established themselves in an internationally recognised market, Smithfield (Forshaw & Bergtröm Reference Forshaw and Bergström1980: 35). To have had a son apprenticed to a butcher appears to have been an aspiration (Jones Reference Jones1976: 15). From the later medieval period in Britain and other parts of Europe where similar guilds were established, butchers and others involved in the animal body-part trades could become economically salient and enjoyed a respected status (Yeomans Reference Yeomans2008; Seetah Reference Seetah, Pluskowski, Kunst, Kucera, Bietak and Hein2010).

Negative associations were not absent, and these too are revealing: ‘Many have a great aversion to those whose trade it is to take away the lives of the lower species of creature. A butcher is a mere monster, and a fisherman, a filthy wretch,’ wrote the Reverend Seccombe (Reference Seccombe1743). At this time, the function of a butcher did not always involve killing the animal, a task that was often undertaken by a slaughter man (Rixson Reference Rixson2000: 96). The point is that negative attitudes could derive from associations with death, although the evidence suggests that both legislators and the public were more concerned with the quality of the product, pricing, and corruption. Numerous cases exist where butchers were held accountable for selling spoiled meat or flouting laws designed to prevent the sale of meat during Lent or on Sundays (Jones Reference Jones1976: 123).

Finally, although rooted in processes that have a deeper antiquity, at least since the post-medieval period in Europe and North America, the drive toward modernity has had major implications for the place and role of the contemporary butcher (Otter Reference Otter and Lee2008; Pacyga Reference Pacyga2015). The removal of animal slaughter from the high street is strongly linked to legislation designed to control physical waste and pollution (Perren Reference Perren and Lee2008). Vialles suggests that in post-medieval Europe, ‘an ellipsis between animal and meat’ (Vialles Reference Vialles1994: 5) led to the establishment of designated abattoirs and the categorical removal of slaughter from the urban domain and public sight (Lee Reference Lee2008: 47). The situation is an intricate one. For Britain, there was a strong connection between waste and disease, in a modern sense. This resulted in reforms to public health legislation, led in part by Edwin Chadwick’s report on the sanitary conditions of the working poor (Chadwick Reference Chadwick1843). However, the circumstances of change also revolved around the transformation of humanitarian attitudes toward animals and a process to ‘civilise slaughter’ (Otter Reference Otter and Lee2008: 89; MacLachlan Reference MacLachlan and Lee2008: 107). Also important were the economic drivers that pushed for a greater regimentation of the process of slaughter and butchery (MacLachlan Reference MacLachlan and Lee2008: 107–27). These attitudes, during a period of globalisation of trade and intensification in local urbanization, found ready adoption in many parts of the United States and Mexico (Horowitz Reference Horowitz2006: 1–18; Pilcher Reference Pilcher2006: 1–15). However, with the industrialisation of meat production, i.e., increased mechanisation of carcass processing, the butcher and the craft were marginalised in an entirely new way. In effect, the skill disappeared. In its place, individuals undertook precise and specific mechanical steps within the process, and an increasing specialisation of tasks and functions occurred, resulting in a mode of butchery that mimicked the factory line (Gerrard Reference Gerrard1964: 86–101). ‘Once the slaughter began, it seemed endless. In the cattle kill … the line moved with ferocious speed never before demanded of workers’ (Pacyga Reference Pacyga2015: 70).

While this survey has marshalled a variety of perspectives that could usefully be employed to better position the butcher, it is also important to recognise limitations. Coming back to the Asian examples, professions that to some minds are dégoûtant, such as collecting ‘night soil’ (human excrement), did not result in outcaste status in Japan (Passin Reference Passin1955). Conversely, leather workers and tanners were also considered as outcastes even though they would not have killed the animals themselves. Shoemakers were considered base because Confucianism considers the feet as an opposing force to the head and therefore unvirtuous. In these cases, sinning by proxy led to these groups also being identified as the moral ‘other’ (Page Reference Page1999: 128–9). The examples illustrate how facile the reasoning could be and how easy it was for outcaste status to be attributed; such convoluted reasoning would render any archaeological view opaque.

Furthermore, deciphering the view of a particular profession in the past requires a large measure of caution, particularly when relying on historic accounts. Swift wrote that ‘physicians ought not to give their judgment of religion, for the same reason that butchers are not admitted to be jurors upon life and death’ (Swift Reference Swift1843: 385). On the surface this may suggest that the very nature of those who killed, butchered, and processed carcasses was called into question and that the morality of butchers was heavily scrutinised as a result of their profession. However, Swift, an early modern satirist and a cleric, sought to provoke a reaction, and more importantly, his comments were probably aimed directly at physicians and not at butchers. With increased secularisation of society during this time, and growing reliance on doctors to administer a ‘cure’ for ailments, rather than a vicar, it is plausible that these statements are a reaction to the threat to his profession and the sanctity of religion.

Stratification through the Lens of Archaeology

Inequality, in one form or another, is universal. As archaeologists, how can we approach a more complete understanding of social divisions, and how do animal remains fit into this paradigm? Once again, the emphasis rests on the knowledge and skills of butchery and butchering itself, but viewed from the external perspective, by society at large. In this way, we observe how practice can shed a light on a more complex and universal topic: identity.

An important body of research in zooarchaeology has looked at the individuals who process animals from economic and cultural points of view (Mooketsi Reference Mooketsi2001; Pluskowski Reference Pluskowski and Pluskowski2007: 110; Yeomans Reference Yeomans and Pluskowski2007: 98). Building on this body of literature in terms of scale is research that links bone distribution and site organisation to interpret occupational topographies (Benco et al. Reference 231Benco, Ettahiri and Loyet2002). By adding to this archaeological view, the preceding examples seek to better understand mind-set – as it relates to those who handle carcasses. This then serves as a point of departure for understanding social organisation. All share three common factors that are relevant within an archaeological context. They exhibit culturally sanctioned attitudes toward hygiene, are driven by religious ideology, and would likely leave specific material signatures discretely positioned within the landscape. Bolstering these points is the fact that the perpetuation of outcaste status is invariably reinforced by endogamy. Thus, the association between activity and social stratification becomes rooted in heredity and fixed within specific locations over generations.

These features provide a usable framework from which we might better understand social structure from cut mark data. The following depends on one assumption: in cases where particular practices are adhered to, perhaps over generations, these would illustrate specificity in the modes of processing that were particular to individual groups. Such ‘archaeological butchery groups’ could reveal much about the agent as well as the relationship between agents at different social levels and the religious practice of a site’s inhabitants. It also potentially situates the place of technological knowledge within the context of expressing social ideals.

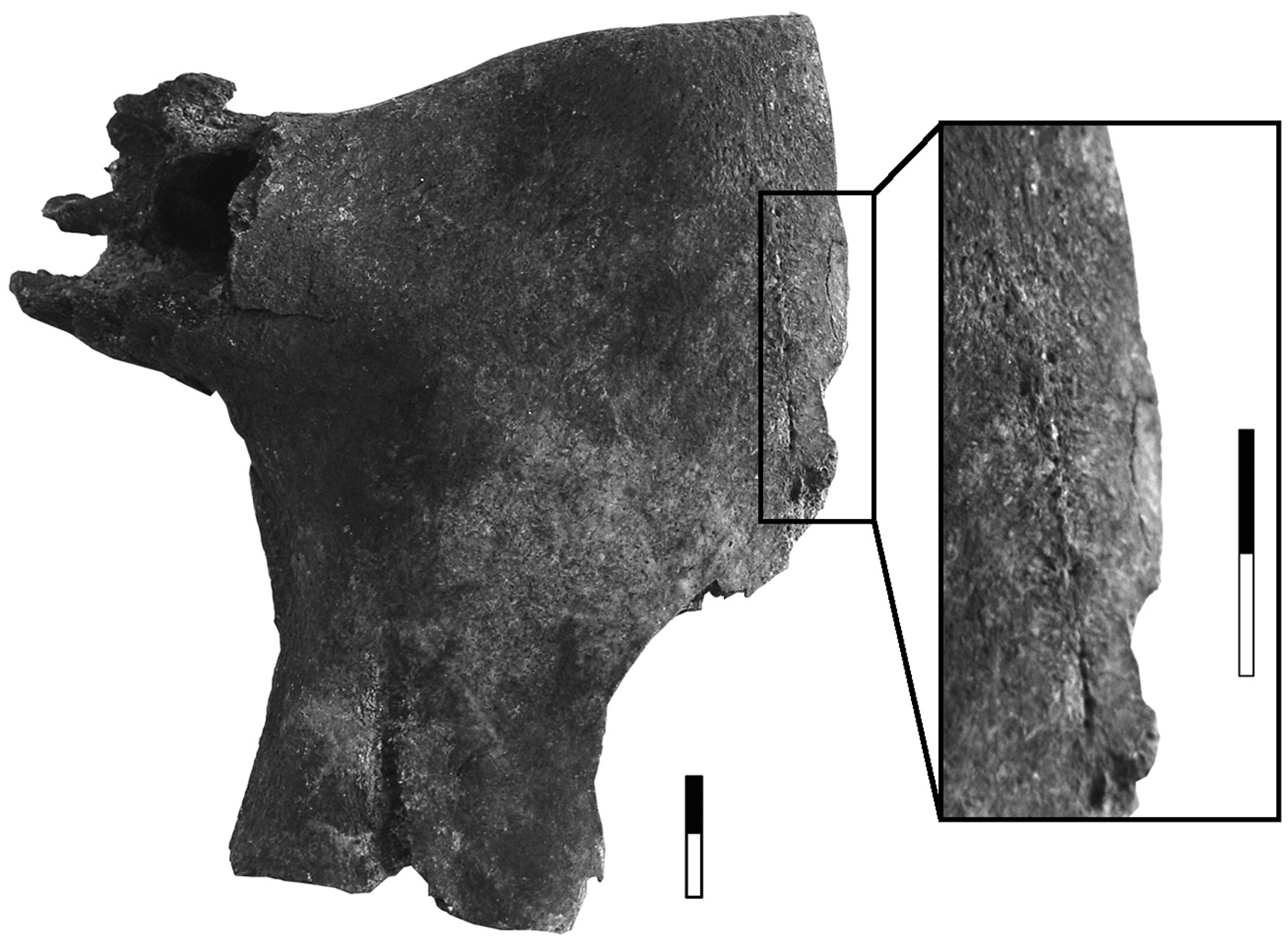

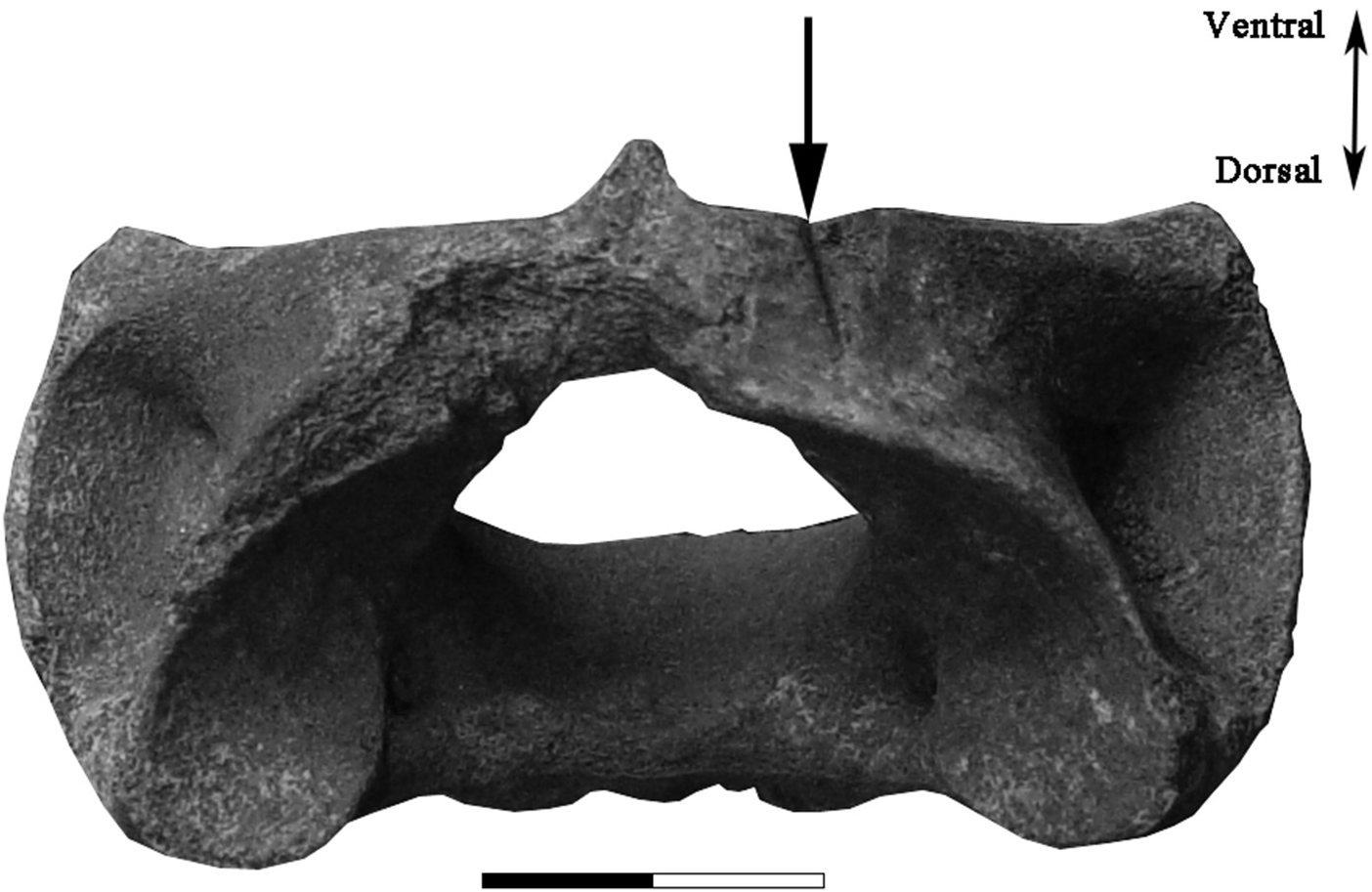

In the above case studies, religion and cosmology have been underlying drivers. Judaism and Islam follow strict rules that dictate slaughter; for Hindus and Buddhists, killing itself is sinful. In contrast, although there are guidelines directing which categories of animal flesh can be consumed and when, Catholicism is relatively free of regulation as it pertains to carcass processing. Thus, one would expect to see ‘normal’ practices for slaughtering, which is precisely what was noted from Tarbat, Portmahomack, in Scotland. The site, perhaps the earliest Pictish monastery and as such an important example of a monastic enclave (Carver Reference Carver2008), demonstrates how, in the absence of ecclesiastic indoctrination to define methods of slaughter, common practice prevailed. Poleaxing was employed to kill cattle, and pigs were slaughtered by sticking (Fig. 4.1a,b), two methods widely used for slaughter of these species. Contrasting these examples with those where the technique for slaughter is more rigidly defined provides evidence for religious drivers of slaughter (Cope Reference Cope, O’Day, Neer and Ervynck2004; Greenfield & Bouchnick Reference Greenfield, Bouchnick, Amundsen-Meyer, Engel and Pickering2011).

Fig. 4.1a Poleaxe use on cattle (cranium); note the semi-circular puncture shown in the inset, as well as the depressed, but articulated, fractured bone suggesting radiated impact, typical of poleaxe use.

Fig. 4.1b ‘Sticking’ used to slaughter a pig, ventral aspect of atlas bone (first vertebrae) shown. The mark (arrowed) shows that the point of a blade was inserted into the throat; probably with the animal laid on its back.

Additional features that might be indicative of social differentiation include divisions of labour and evidence for hierarchical consumption. The scapula from medieval Toruń Town, Poland (Fig. 7.1, Chapter 7) and research drawn from medieval and post-medieval Britain (Yeomans Reference Yeomans and Pluskowski2007) illustrate differentiation of tools and crafts. This points to a likely compartmentalisation and segregation of animal processing, and potentially supports the involvement of different individuals. This is not in and of itself indicative of social stratification, but rather, in a highly specialised system that has developed over generations, we may see evidence of well-defined tasks. Finally, there is good evidence for differentiation during consumption, as reported by Stokes (Reference Stokes and Rowley-Conwy2000) from Roman Britain, and Sykes (Reference Sykes and Pluskowski2007) for the medieval context.

Moving from the cut mark data to spatial context, and in recognition of miasma theory (Rawcliffe Reference Rawcliffe2013: 8–9), one outcome of having to deal with effluent waste from animal processing is that these trades are usually grouped together. Thus, occupational segregation creates vocational topographies, or ‘geographies of slaughter’ (Day Reference Day2005). These have been documented from a wide range of settings, in Europe, i.e. Britain (Goldberg Reference Goldberg1992: 64–6 for York; Yeomans Reference Yeomans and Pluskowski2007: 103 for London), Asia (Passin Reference Passin1955 for India; McClain Reference McClain2002: 101 for Japan), and Africa (Horowitz Reference Horowitz1974 for Niger; Weedman Reference Weedman2006 for Ethiopia). Spatial and logistical practicalities, such as the need to be close to water, serve as important drivers (see example from York, in Goldberg Reference Goldberg1992: 64). However, social factors, for example, the status of those involved in these professions, must also have gone hand in hand with these practical considerations.

Routes to Professionalisation of Practice

Thus, to return to the archaeological case studies, the butchery evidence reveals much about the technological construction and specialisation of tools, as well as the occurrence of standardised (professional?) practices. These, in turn, can be used to infer craftsmanship and indeed trades focused on specific processing. Archaeological lines of evidence from the butchery record and indications of occupational topographies can be combined with historical accounts of particular building types, i.e. bathhouses, that indicate cultural attitudes to hygiene. Additional depth can be added to reveal ideologies as might be evident through depictions from religious iconography (Gould Reference Gould1960). Religion can also be viewed indirectly. Lawrence and Davis (Reference Lawrence and Davis2011: 242) point to the presence of tinned fish and the relative absence of alcohol containers as indicative of adherence to Islamic edict by Afghan cameleers in Australia, the first Muslims to settle there, from the 1860s. Fish was not subject to halal, and thus tinned fish was a valuable source of protein. From this multidisciplinary perspective, we can go much further than an investigation of animal exploitation; the faunal evidence helps us to better understand community organisation (Ervynck Reference Ervynck, O’Day, Van Neer and Ervynck2004; Pluskowski Reference Pluskowski2010). Zooarchaeologists are increasingly cognizant of the diversity of social relationships that take place between humans and animals, and new approaches help to delve more deeply into these interactions.

Despite complications, the ubiquity of social division renders this topic of universal relevance for archaeology. Equally relevant are the ways in which zooarchaeology can provide insight into ‘how’ social divisions are manifested. There is far more to investigate than the ostracism of people associated with specific trades. Through constructed identities we gain insight into aspects of culture contact. Conquest appears to be a crucial link in the creation of outcastes. Outcastes often derive from indigenous communities, which are considered technologically, militarily, or culturally backward. The untouchables of India are thought to derive from remnant Dravidians conquered by northern Aryan groups and progressively marginalised into menial tasks (Gould Reference Gould1960). This situation is replicated in Ethiopia (Todd Reference Todd1978). Both these contexts also illustrate the physiological underpinnings of these social divisions; marginalised groups are invariably considered ‘primitive’. In Japan, Eta apparently derive either from ancestral Negrito people from the Philippines, a Hindu tribe called Weda, or Korean immigrants (Price Reference Price, Reilly, Kaufman and Bodino2003: 41). The fact that endogamy is a common feature also speaks of the need to preserve cultural, physical, and moral purity. This theory of ‘origins’ has been much debated (De Vos & Wagatsuma Reference De Vos and Wagatsuma1966: 11–12; Todd Reference Todd1978; Pankhurst Reference Pankhurst1999) but remains to be tested through archaeological data.

Concluding Comments

Whether discussing medieval Europe, Hindu India, or Shintō Japan, the act of killing animals, preparing their carcasses, and consuming their flesh has been associated with social or spiritual pollution. In contrast, medieval Europe offers both a counter and complement to these examples; there certainly were negative connotations, but these were not grounded in the act of slaughter per se.

In the European case, as part of the push for Western modernity, legislation to enact controls over physical pollution saw the gradual displacement of animal slaughter from the high street, giving rise to the abattoir. For the archaeological contexts, the attendant social facets that surround the crafts and materials we study are often elusive. However, this does not preclude us from using the rich ethnographic literature and modern analogy (Chapter 5) to inform our interpretation. Furthermore, the materiality of crafts can serve as a means of assessing technological developments (Chapter 6). Uniting the ethnographic and technological contexts is important in terms of recognising and capturing the entire scope of ‘social influences’. For butchery, these are exerted on carcass processing itself but also exist as attitudes at a national level, which can result in both positive and negative associations for the occupational groups involved in the activity.

Scholars from numerous disciplines have demonstrated the ways in which butchery and butchering have had a profound impact on economy at a global scale, through meat consumption. Similarly, the universal and complex nature of social impacts has to be recognised. Acknowledging this point serves to temper and enrich our interpretations and connects us to the people behind the practice. It is interesting to consider that, as a consequence of ostracism and endogamy, there is an assurance to some degree that knowledge and techniques associated with the scheduled professions are transmitted from one generation to the next. The caste system effectively functions to embed geographic boundaries and practical skills in portions of society, particularly for those of a lower station. This phenomenon has been brought to our attention through anthropological enquiry. However, as the Canary Island example and cases from Tarbat and Toruń illustrate, they are also likely to be present in the archaeological record and could help explain important details of how craft knowledge is disseminated through time and across space, or why it is not.

Thus, whether from the perspective of localised ethnographies, systems of social differentiation based on associations with animal bodies, or newly industrialised settings where the butcher is effectively a factory worker on the lowest rung of the social ladder, there are opportunities to enrich our interpretations of the past. Once again, restating a point that is axiomatic for this book, the overarching emphasis on the study of meat and cut marks has circumvented our attention away from the craft and the practitioner, and this is to the detriment of our collective scholarly enterprise. Looking toward the future, this chapter has provided a starting point for imagining how a range of datasets could be judiciously weaved together to create a more intricate tapestry of past social attitudes to those involved in animal body-part crafts. This not only provides better ways to understand butchery and butchering in the past, it also uses cut mark data in more creative ways to better understand sociality. The role of the butcher is conceptualised in each society; whether or not it is acknowledged and articulated, no society remains ambivalent or ignorant of butchery.