Book contents

- The Faust Legend

- The Faust Legend

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Prologue

- Chapter 1 The Background of the Faust Legend

- Chapter 2 Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus

- Chapter 3 Goethe’s Faust

- Chapter 4 Post-Goethe Dramatic Versions of the Faust Legend

- Chapter 5 Cinematic Fausts

- Epilogue

- Notes

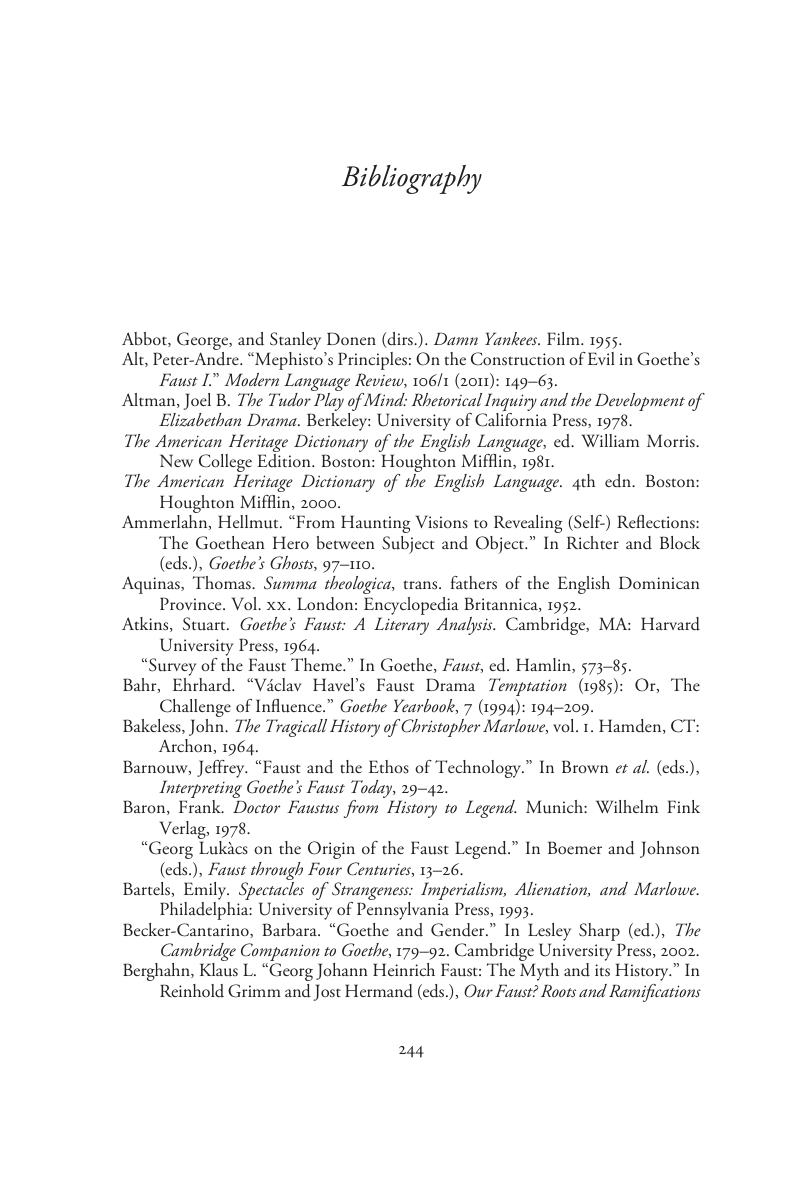

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 02 September 2019

- The Faust Legend

- The Faust Legend

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Prologue

- Chapter 1 The Background of the Faust Legend

- Chapter 2 Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus

- Chapter 3 Goethe’s Faust

- Chapter 4 Post-Goethe Dramatic Versions of the Faust Legend

- Chapter 5 Cinematic Fausts

- Epilogue

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- The Faust LegendFrom Marlowe and Goethe to Contemporary Drama and Film, pp. 244 - 256Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2019