Eighteenth-Century Manners of Reading

Eighteenth-Century Manners of Reading Book contents

- Eighteenth-Century Manners of Reading

- Eighteenth-Century Manners of Reading

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Figures

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 The ABCs of Reading

- Chapter 2 Arts of Reading

- Chapter 3 Polite Reading

- Chapter 4 Ordinary Discontinuous Reading

- Chapter 5 Reading Secret Writing

- Afterword

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

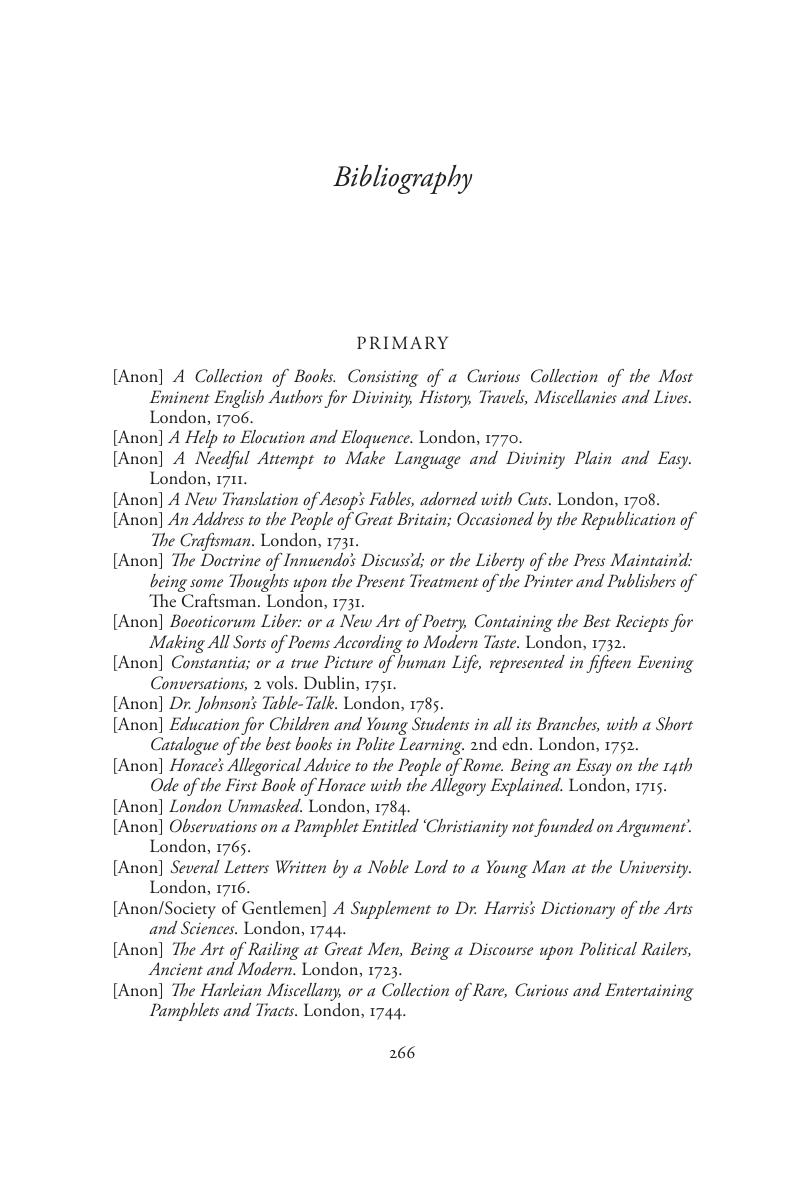

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 October 2017

- Eighteenth-Century Manners of Reading

- Eighteenth-Century Manners of Reading

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Figures

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 The ABCs of Reading

- Chapter 2 Arts of Reading

- Chapter 3 Polite Reading

- Chapter 4 Ordinary Discontinuous Reading

- Chapter 5 Reading Secret Writing

- Afterword

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Eighteenth-Century Manners of ReadingPrint Culture and Popular Instruction in the Anglophone Atlantic World, pp. 266 - 287Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2017