Book contents

- Designing Boundaries in Early China

- Designing Boundaries in Early China

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Maps

- Acknowledgments

- Chronology

- Preamble

- 1 The Basis of Ancient Borders

- 2 The Visual Modeling of Space in Text and Map

- 3 Movement and Geography

- 4 The Perception of the “State”: The Internal Definition of Sovereign Space

- 5 The Perception of the “Enemy”: The External Definition of Sovereign Space

- 6 Transgressions: Rupturing the Boundaries Between Sovereignties

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

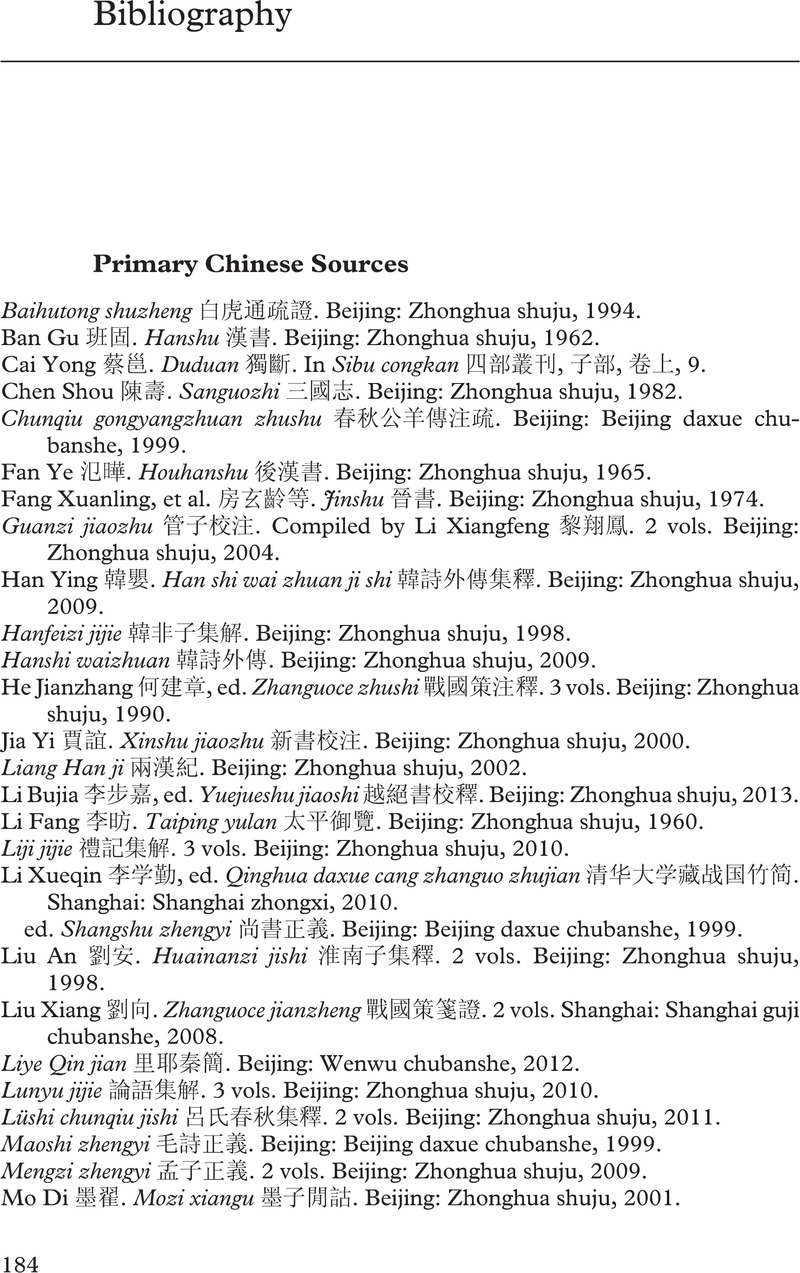

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 19 November 2021

- Designing Boundaries in Early China

- Designing Boundaries in Early China

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Maps

- Acknowledgments

- Chronology

- Preamble

- 1 The Basis of Ancient Borders

- 2 The Visual Modeling of Space in Text and Map

- 3 Movement and Geography

- 4 The Perception of the “State”: The Internal Definition of Sovereign Space

- 5 The Perception of the “Enemy”: The External Definition of Sovereign Space

- 6 Transgressions: Rupturing the Boundaries Between Sovereignties

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Designing Boundaries in Early China , pp. 184 - 196Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2021