Prologue: Shibden Hall

It’s 6 March 2020, a bright cold day in Halifax, and Shibden Hall is closed to the public. Not because of Covid-19 – the first UK lockdown hasn’t happened yet – but because the boiler’s not working. Angela Clare from Calderdale Museums is waiting at the gate to show us round: me, my friend Harriet from Manchester and two American fans of Gentleman Jack who didn’t know the house was closed and happened to turn up at just the right moment. ‘Wear lots of layers,’ Angela had warned me; ‘it’ll be freezing.’ There’s a school visit going on as well, and our paths keep almost crossing with troops of primary school children wearing mob caps and aprons. After the house, we go out into the carriage barn, and Angela gestures through the doorway to the courtyard of the Folk Museum, with its reconstruction of shops and crafts. ‘Everything beyond this point is fiction,’ she says. I take a photograph on my phone, but when I check it later there’s nothing there.

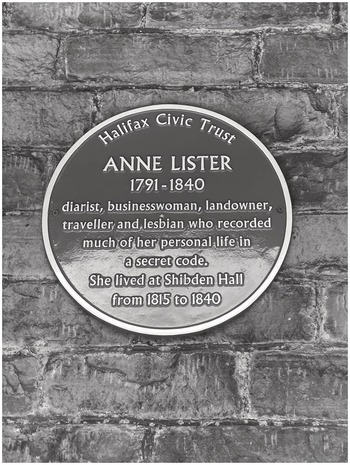

My photograph of the plaque on the wall at Shibden comes out fine. I was there nearly a year ago for the unveiling, on Lister’s birthday, 3 April 2019. That was a cold wet day. People huddling under fleece blankets in the unheated carriage barn to hear Helena Whitbread and Jill Liddington give their talks, next to the one electric heater. The mayor, speaking warmly about how Anne Lister had been part of his life as a teenager in Halifax, because Helena was a friend of his mother and had talked about Anne Lister at his mother’s kitchen table. The rain, finally stopping just in time for the mayor to unveil the plaque. Lots of people taking photographs of Helena and Jill underneath it.

None of us in the UK or the USA had seen Gentleman Jack at that point, though we were all keen to know how it would turn out. We had no idea how much was about to change, how many conversations about Anne Lister would be sparked, in and beyond Halifax and across the globe. How many people would beat a path to her door, would make the pilgrimage to Halifax and Shibden in search of her.

Figure 6 Shibden Hall plaque.

What was already clear, in that pre-Gentleman Jack spring of 2019, was just how powerful a thing a plaque could be, and what fierce emotions it could provoke. By the time the Shibden Hall plaque was unveiled, there had already been not one, but two plaques commemorating Anne Lister’s place in LGBTQ+ history, both of them at the same site in York, though not at the same time.

A Tale of Two Plaques

On 24 July 2018, York Civic Trust unveiled the first rainbow plaque in the UK, in recognition of Anne Lister and her union with Ann Walker.1 The plaque, outside the church of Holy Trinity in Goodramgate, York, where the two women celebrated their union by taking communion together, immediately sparked controversy for its wording: ‘ANNE LISTER / 1791–1840 / Gender-nonconforming / entrepreneur. Celebrated marital / commitment, without legal / recognition, to Ann Walker / in this church. / Easter, 1834.’

As Kit Heyam, co-organiser of the Rainbow Plaques project in York, recalls: ‘within hours of the plaque unveiling, I was receiving angry and often abusive messages on social media. Within a day, this had escalated: a petition was launched against the plaque and several people had got hold of my work phone number.’2 The online petition, which accused the organisers of erasing lesbian history and demanded that the plaque be replaced with one that would describe Lister as a lesbian, gained upwards of two thousand signatures in its first week and was widely reported in the news media.3 On 3 September, York Civic Trust announced its decision to change the plaque’s wording.4 A consultation period was introduced on the proposed new wording from 30 October to 25 November 2018, and on 10 December the Trust announced that 95 per cent of those who had responded to the survey were happy with the revised wording, which was as follows:

ANNE LISTER / 1791–1840 / of Shibden Hall, Halifax / Lesbian and Diarist; took sacrament here / to seal her union with Ann Walker / Easter 1834.5

The new plaque was unveiled on 28 February 2019, to mark the end of LGBT History Month in York; York Civic Trust also took the opportunity at this point to correct the rainbow border of the plaque, which had initially been upside down. A talk by Helena Whitbread followed the unveiling of the new plaque – a significant choice, given Whitbread’s pioneering role in presenting Lister’s diaries to the world and her unwavering view of Lister as a lesbian.6

At the unveiling of the Shibden Hall plaque in April 2019, a representative from the Halifax Civic Trust commented privately that they had learned from the York experience, and that the word lesbian would definitely be on this one. Unlike the two versions of the York plaque, the Shibden plaque didn’t try to sum Lister up in two words (‘gender-nonconforming entrepreneur’ versus ‘lesbian and diarist’), but offered a more expansive description: ‘Anne Lister / 1791–1840 / diarist, businesswoman, landowner, / traveller and lesbian who recorded / much of her personal life in / a secret code. / She lived at Shibden Hall / from 1815 to 1840.’ In fairness, the Shibden plaque had an easier task than the York one; its matter-of-fact statement about Lister’s connection with Shibden Hall left more space to describe her, and no room for controversy.

Figure 7 Lister/Walker plaque.

One of the problems with the York plaque was that the Church of England’s continuing refusal to recognise same-sex marriages necessitated careful wording about what exactly had happened between Lister and Walker; the desire to claim the church as the site of one of the first same-sex marriages, or the first lesbian wedding, could not be fully realised.7 Moreover, as Simon Joyce notes in his article ‘The Perverse Presentism of Rainbow Plaques’, Lister’s diary entries don’t fully support this claim: Lister and Walker did not celebrate the anniversary of taking communion together at the church, but instead marked the date when they had agreed to make the commitment to each other.8 Joyce suggests that there is a parallel between the controversy over the York plaque and how Gentleman Jack ‘downplays [Lister’s] gender nonconformity in order to focus instead on her relationship to Ann Walker as a prototypical example of marriage equality’.9

Joyce argues that both sides of the plaque debate were based on presuppositions that would have made no sense in Lister’s historical context, namely ‘that we each have a way of self-identifying in terms of gender and sexuality and that this should be considered an unimpeachable truth about ourselves’.10 The term ‘gender-nonconforming’, in his view, was rooted in ‘a fantasy of stable identity that was just as anachronistic as the labels that had been rejected’.11 Discussing Jack Halberstam’s reading of Lister in Female Masculinity as closest to a ‘stone butch’ in terms of modern identity, Joyce says that if Halberstam is right, ‘the York Civic Trust’s first instinct was actually more grounded in Lister’s own sense of self than its second’ and that the impulse to define Lister as ‘a lesbian avant la lettre’ might be more anachronistic than calling her gender-nonconforming.12

Anachronism was only part of the story, however, and not the part that made most noise. As Heyam recalls, ‘Some of the angry messages (and all of the abuse) came from anti-trans activists who saw Anne’s plaque as a symptom of how, in their eyes, advances in trans rights were eroding the rights of lesbians.’13 Heyam is at pains to point out that ‘the majority of anger and hurt came from lesbians and bi women who were explicitly supportive of trans rights, but still felt Anne was an important part of their historical community’, and that respect for these women’s concerns prompted the revision of the plaque.14 Nevertheless, the plaque’s wording was widely interpreted as having more to do with contemporary LGBTQ+ politics than with the potential for anachronism in applying modern identity categories to historical figures. York Civic Trust’s press statement that the choice of ‘gender-nonconforming’ rather than ‘lesbian’ was an attempt to ‘future-proof’ the plaque’s description of Lister did not help matters; a discussion in the comments on a Facebook post sharing York LGBT Forum’s announcement about the plaque interpreted the reference to ‘future-proofing’ as a sinister prediction of further lesbian erasure.15 A blog post by the linguistics professor Deborah Cameron linked the plaque’s wording to a recent Buzzfeed article about evolving attitudes to gender identity, particularly amongst young people, and the implications of those changes for the future of supposedly old-fashioned binary labels such as gay and lesbian; the issue about the plaque’s wording, Cameron concluded, was not ‘what we can’t know about the past, it’s what we don’t agree on in the present’.16 Shon Faye, who discusses the controversy in a chapter which begins with the disruption of the 2018 Pride parade in London by the anti-trans group Get The L Out, a couple of weeks before the unveiling of the York plaque, comments: ‘This fierce dispute over the precise description of a dead Victorian woman is more about contemporary LGBT politics than it is about history.’17

Heyam’s account of the Rainbow Plaques project is surprising and at times moving. As they explain, the original impetus for Lister’s plaque came from an event Heyam co-organised for York LGBT History Month in 2015, in which people were invited to create cardboard rainbow plaques that marked spaces of significant LGBTQ+ history – personal, local or global – which would be displayed for twenty-four hours across the city. Two of these plaques marked Lister’s association with York, one at her school, King’s Manor, and one at Holy Trinity Goodramgate. Participants in the project were keen for Lister to have a ‘real’ plaque at the church, which they saw as ‘the site of one of the first lesbian marriages in the UK’.18 This plan was eventually realised in 2018, through a collaboration between York Civic Trust and York LGBT Forum, in conversation with the Churches Conservation Trust, but something clearly went badly wrong in the shift from that creative, community-led, local and temporary project to a permanent memorial.

As Heyam says, the response to the first York plaque showed ‘just how many people Anne Lister was important to, and how few of those people our consultation had managed to reach’. Rather than being a deliberate decision motivated by concerns about anachronism, the omission of the word ‘lesbian’ from the plaque seems to have been the result of that failure: ‘No one had highlighted this word as important in our consultation,’ Heyam says, ‘and (with what seems in retrospect like enormous naivety) I’d assumed that this was because everybody knew Anne Lister was a lesbian.’19 Such naivety is indeed startling; given the long and painful history of lesbian invisibility, what ‘everybody knows’ is precisely what can’t be taken for granted, and it does seem astonishing that nobody realised this was going to be a problem. Heyam’s explanation of ‘gender-nonconforming’ is perhaps less surprising, though it contrasts strikingly with Joyce’s reading of the term as rooted in ‘a fantasy of stable identity’. For the decision-making committee, Heyam says, ‘this was a description of Anne’s behaviour … But to many people, it read as a label for Anne’s identity: a statement that they weren’t a woman, and were therefore not a lesbian either.’20 (Heyam uses they/them pronouns for the historical figures in their book, for reasons they outline in their Author’s Note.)

Heyam expresses sadness that the new plaque ‘makes no mention of Anne’s gender nonconformity’ and that ‘we’ve lost an opportunity to commemorate how Anne represents an overlap between trans history and lesbian history’.21 They argue that we should ‘focus less on the impossible task of identifying which historical figures are “really” trans and which aren’t, and more on acknowledging the diversity of creative, non-conforming and fluid approaches to gendered dress in the past, and appreciating both the individuality and the shared experiences they represent’.22

When the news about the first York plaque was announced, in the summer of 2018, I was struck – as many people were – by the discrepancy between the BBC news headline, ‘Plaque in York Honours “First Modern Lesbian” Anne Lister’, and the wording of the plaque itself, which described Lister as ‘Gender-nonconforming entrepreneur’.23 I knew very quickly that I wanted to write something about Lister, labelling and identity categories, but I also had a sinking feeling about what I was letting myself in for. And I felt caught in a difficult in-between space, in my own response to that initial news story and the issues it raised. I was aware that some of the loudest voices in the outcry against lesbian erasure in the original wording of the York plaque were coming from a position of intense and persistent hostility to trans and queer identities, a position that has been increasingly visible in the UK in the past few years.24 As part of my work for this chapter, I read all the comments on the original online petition, an experience I found deeply disheartening. To be clear: I identify as both queer and lesbian; I want my queer history to be inclusive and nuanced, but I had my own pang about the original wording of the plaque. I wanted the word ‘lesbian’ to be there, even while knowing that using it would be anachronistic, and probably not what Lister would have wanted. ‘Gender-nonconforming entrepreneur’ felt like a very unsatisfactory and partial description.

Public perceptions of Anne Lister, including my own, were soon to be influenced by a new factor: Gentleman Jack was broadcast from 22 April to 10 June 2019 in the USA and from 19 May to 7 July in the UK, nicely timed to coincide with Pride Month in each case. Shibden Hall rapidly became a site of pilgrimage for fans of the series; visitor numbers to the house trebled, and media interest in Anne Lister soared. Lots of well-meaning straight colleagues started asking me if I’d seen Gentleman Jack or heard of Anne Lister.

In the run-up to the UK broadcast of the television series, I was interviewed by a journalist, Rebecca Woods, who was writing a piece about Lister for the BBC website.25 Our email correspondence about Lister and questions of identity made me think about a conversation earlier in 2019 with Dominique Bouchard from English Heritage, about academia and public engagement on LGBTQ+ topics. Dominique had suggested then that we might have to be less nuanced in presenting queer history for a general audience, if the result of trying to be nuanced is that we end up not saying anything at all or end up obscuring or erasing the queerness of historical subjects. In my discussions with Rebecca Woods, the journalist, I tried to emphasise the importance of Lister’s place in lesbian history, but I kept getting caught between wanting to say ‘yes, of course she’s a lesbian’ and being acutely aware of the problems with ascribing modern identity categories to historical subjects, and indeed with ascribing lesbian identity in particular to Anne Lister, the woman so often labelled ‘the first modern lesbian’.26

The Dead Sea Scrolls of Lesbian History

In 2009 or 2010, the historian Laura Doan was approached by a researcher asking if she would be willing to talk about Anne Lister for a television documentary that would present Lister as the first modern lesbian. Mindful of the problems with identity history, Doan explained that she couldn’t talk about Lister as unproblematically an example of lesbian identity. The researcher, a bit flustered, went off to check with the programme-makers and came back saying, ‘I’m sorry, we really need her to be a lesbian!’27

Doan, not surprisingly, did not take part in the documentary, which was made to accompany James Kent’s 2010 film, The Secret Diaries of Miss Anne Lister. Capitalising on the release of the film, Virago published a revised version of Helena Whitbread’s original 1988 selection from Anne Lister’s diaries, I Know My Own Heart, retitled The Secret Diaries of Miss Anne Lister. Above a still from the film showing Maxine Peake and Anna Madeley as Anne Lister and Mariana Lawton, the front cover bears a quotation from Emma Donoghue: ‘The Lister diaries are the Dead Sea Scrolls of lesbian history; they changed everything.’28

That was rather how it felt, in 1988; the revelations of an early nineteenth-century woman’s sexual desire for and sexual exploits with numerous other women were so astonishing that some people actually thought they must be a hoax. It was just too good to be true.29 The version of lesbian history which Terry Castle mischievously described as ‘no lesbians before 1900’ was overturned by Lister’s detailed record of her love affairs, flirtations, seductions, ‘grubbling’ (i.e. groping) and multiple ‘kisses’ (her term for orgasms).30 Lister’s declaration, ‘I love, & only love, the fairer sex’, was taken up as a statement of lesbian sexual identity, and her assessment of the Ladies of Llangollen’s relationship as ‘something more tender still than friendship’ offered an exhilarating sense of identification.31 Lister’s use of a personal code – her ‘crypt hand’ – for passages about her sexual activities provided a wonderful metaphor for what had been hidden from history.

Not everyone accepted this view of Lister or her revolutionary effect on lesbian history. In a 2019 blog post on the representation of butchness in recent television dramas, Jack Halberstam noted disapprovingly that there is ‘a tendency now to regard Lister as a “lesbian”’. Criticising Gentleman Jack for making ‘that same mistake’, Halberstam stated that

no such word would have been used during Lister’s life-time and the markers of Lister’s difference from other women concerned his/her cultivated masculine appearance and his/her desire for women. S/he did not understand herself to be part of a community of others like herself and s/he considered her partners to be women while s/he was something else, something closer to manhood.32

Another queer theorist, Annamarie Jagose, similarly insists that ‘Lister’s many sexual partners do not understand themselves, any more than she understands them, as sharing with Lister a sexual preference, let alone anything like a sexuality. Without exception, Lister’s sexual relations with women are not defined as transacted between subjects of the same gender.’33 As Chris Roulston suggests, ‘For eighteenth-century scholars, Lister has repeatedly created a crisis of classification. Labeled as both “the first modern lesbian” and as an example of female masculinity, Lister appears to inhabit and simultaneously to elude the various categories in which she has been placed.’34 Caroline Baylis-Green argues that ‘Lister’s Diaries show her inhabiting a number of differently gendered personae and subjectivities, which fit more comfortably within a genderqueer or non-binary framework.’35 Simon Joyce suggests that one of the difficulties for readers of Lister’s diaries is ‘the absence of stable identity signifiers’ but also Lister’s need for them, which means that ‘she tacks between a number of sexual registers: same-sex desire, the Romantic language of intimate friendship, a language of gender transitivity, and a masculine discourse of sexual libertinism’.36

‘I look within myself & doubt’: Lister’s Self-Construction

Despite all these caveats, the ‘first modern lesbian’ label has adhered to Lister with remarkable persistence, not always helpfully. Jill Liddington’s consciously careful description of Lister’s diaries as ‘the earliest and most candid first-person experience of living a lesbian life’ suggests that what’s important is not identity, but experience, and particularly the recording of that experience.37 One of the drawbacks of the ‘first modern lesbian’ label is that it obscures Lister’s work as a writer, presenting the diaries as a straight-from-the-heart outpouring of authentic lesbian emotion. Lister was a self-conscious writer, who reread, indexed and reflected on her own writing, and who thought about becoming a published author.38 The record of her life comes to us mediated through her deliberate self-construction – she is our source, and that’s as problematic as for any other first-person narrative, memoir, journal or epistolary record. Whoever we think she’s performing for, even if it’s just herself, the sense of an audience and an effect complicated any attempt to see this as an unmediated, innocent or transparent account of the heart she claimed to know so well. Even that claim, ‘I know my own heart’, is textually mediated, and quoted in French from the opening page of Rousseau’s Confessions.39 As Anna Clark notes, Lister’s construction of identity drew on Romantic literature (Rousseau and Byron) as well as Greek and Latin classical texts.40

Lister’s sense of her own sexual and gender identity is hard to pin down. Here, engaging with one of the available terms from her own time, she rejects the idea of a connection between her own desires and actions and Sapphism: ‘Got on the subject of Saffic [sic] regard. [I] said there was artifice in it. It was very different from mine & would be no pleasure to me.’41 Lister repeatedly insists on the naturalness of her desire for the fairer sex, and also on her own exceptionalism. Her quotation of Rousseau’s claim to be unlike anyone else has often seemed to be taken too much at face value, so that she ends up bearing the whole evidentiary burden of ‘proving’ lesbian existence in the early nineteenth century. But she is, I think, looking for women like her, not as sexual partners but as models (like the Ladies of Llangollen) or as kindred spirits (like the masculine bluestocking Miss Pickford).42 She has a network of women friends, some of whom are let into the secret of her code or ‘crypt hand’, as Anira Rowanchild notes, and with whom she also shares reading practices and gifts of books, as Stephen Colclough has shown.43 I think there is more of a community here than Halberstam allows for, and I’m interested in the way it keeps dropping out of the picture, whether in critical accounts or dramatisations. Both Gentleman Jack and the 2010 film The Secret Diaries of Miss Anne Lister focus mainly on the pair-bond – Lister’s unhappy relationship with Mariana Belcombe in Secret Diaries, and her courtship of Ann Walker in the first series of Gentleman Jack. I also think there is something prescriptive in Halberstam’s and Jagose’s definitions of Lister as not-lesbian because she doesn’t want likeness or sameness in her sexual relations, or because she does not see herself as the same as the woman she’s having sex with. As I kept finding myself saying to the BBC journalist, it’s complicated.

Lister’s use of her reading for self-construction has been charted by Anna Clark, Stephen Colclough, Chris Roulston, Marc Schachter, Laurie Shannon, Amy Solomons and Stephen Turton amongst others; but she also constructs herself through the mirror of other women who ‘love, & only love, the fairer sex’.44 Lister’s fascination with the Ladies of Llangollen is a particularly rich site for such self-construction, and the effects of her visit to Plas Newydd continue to shape her visions of the life she longs for, in ways that are both practical (her improvements to Shibden’s house and grounds) and imaginative.45 Lister’s assessment of Butler and Ponsonby’s relationship, prompted by Mariana’s question about whether it could be platonic, has been much quoted and discussed:

I cannot help thinking that surely it was not platonic. Heaven forgive me, but I look within myself & doubt. I feel the infirmity of our nature & hesitate to pronounce such attachments uncemented by something more tender still than friendship. But much, or all, depends upon the story of their former lives, the period passed before they lived together, that feverish dream called youth.46

But Mariana is not the only woman with whom Lister discusses Butler and Ponsonby; Emma Saltmarshe, a married friend and former flirt, earns Lister’s disfavour with her contemptuous account of the Ladies and their estate:

Mentioned my having seen Miss Ponsonby … Not a little to my surprise, Emma launched forth most fluently in dispraise of the place. A little baby house & baby grounds. Bits of painted glass stuck in all the windows. Beautifully morocco-bound books laid about in all the arbours, etc., evidently for shew, perhaps stiff if you touched them & never opened. Tasso, etc., etc. Everything evidently done for effect. She thought they must be 2 romantic girls &, as I walked with her to see her off, she said she had thought it was a pity they were not married; it would do them a great deal of good.47

At the risk of over-reading – always a risk with literary critics – I can’t help hearing another layer of meaning in Emma Saltmarshe’s contemptuous remarks about the Ladies’ beautifully bound and displayed books, ‘perhaps stiff if you touched them & never opened’. I’m not saying this is a meaning that Emma intends, though in an earlier journal entry Lister comments on Emma’s own tendency to over-interpretation: ‘She often thinks I mean ten times more than ever entered my head, & fancies smiles & looks & double entendres I never dreamt of.’48 In the wake of Lister’s exchange with Mariana about the non-platonic nature of the Ladies’ relationship, Emma’s suggestion that the Ladies’ female bonding may also be ‘done for effect’, and that they’d be better off married, is a jarring one.

Emma’s attack on the Ladies’ books and reading seems particularly ill-judged, given the importance that books and reading have in Lister’s own life, her sense of her identity and her relationships with other women. When Lister meets Sarah Ponsonby, she compliments Ponsonby on a beautiful bookcase she has noticed earlier, and they discuss reading, translation and poetry. ‘Contrived to ask if they were classical,’ Lister notes, to which Miss Ponsonby replies, ‘No … Thank God from Latin & Greek I am free.’ They also talk about Byron, who has sent the Ladies ‘several of his works’, and Lister asks if Miss Ponsonby has read Don Juan: ‘She was ashamed to say she had read the 1st canto.’ As with the question about being classical, Lister seems to be looking for confirmation of likeness, but with limited success.49

Lister’s visit to the Ladies is a complex event which opens up a world of identification and desire beyond the pair-bond with Mariana. She imagines the possibility of her own desires for domestic partnership with a woman through the Ladies, a process that is strongly evident in her letter to Sibbella Maclean of 19 October 1825. Lister’s attempts to persuade Sibbella to come and spend significant time at Shibden, and get to know her better, are bound up with a painful vignette about Butler and Ponsonby’s declining health in old age.

Do turn to my letter again. Perhaps it is merely in that dry sort of style that you would better understand if you had passed a winter with me at Shibden. I have sometimes, they tell me, a way of saying things peculiarly my own. I smiled to read, that it would not now surprise you ‘so much’, even if I should marry. Be prepared for all things, for I am persuaded ‘joy flies monopolists’; and, if you are ‘one’, and I am not another ‘made to live alone’. I could be happy in a garret, or a cellar with the object of my regard, but, in solitude, a prison or a palace would be all alike to me. ‘Did Mrs B(arlow) ask your opinion as to marrying?’ No! but knowing the circumstances, I have ventured to give it. I have ventured to urge, that the rational union of two amiable persons must be productive of comfort. Trust me, Sibbella, however much you may fancy you differ with me on this subject, we are at heart agreed. There is no pleasure like that of thought meeting thought ‘ere from the lips it part’. Give me a mind in unison with my own, and I’ll find the way of happiness – without it, I should feel alone among multitudes, and all the world would seem to me a desert.

The letter circles around ideas of marriage, as Lister works to persuade Sibbella of their compatibility and the pleasure it can bring, her prose joining Sibbella and herself as two beings not ‘made to live alone’ and insisting that ‘we are at heart agreed’. The union of like minds becomes something close to a kiss, ‘thought meeting thought “ere from the lips it part”’. Lister’s hunger for loving companionship and understanding is palpable here; solitude without love is a prison, and the lack of ‘a mind in unison with my own’ transforms the world into a desert. When Lister turns to the subject of Butler and Ponsonby, presumably in response to something in Sibbella’s letter, her own hopes and fears about the possibility of a long-term relationship with Sibbella (older than Lister, aristocratic, potentially the Eleanor Butler to her Sarah Ponsonby) are never far from the surface:

I was sorry to find it possible for any party of travellers to give such an account of Lady E. B(utler) and Miss Ponsonby. The latter is several years (ten I think) younger than the former, and must be four or five or more years less than eighty. Her first appearance struck me as much, and perhaps, as unfavorably as possible, but there was a flash of mind that bore down on all, and I shall never forget the enchantment that it threw on all around. Lady E. B(utler) I have never seen. She was once clever. What she is, it might be humiliating to inquire, for, in this world, minds, like bodies, do appear to wear out. About the time I was at Llangollen the difficulty of seeing the ladies (any one might see the place) seemed considerable. I regret that it is lessened, but the burden of age may lessen the quantity of self-derived resources and thus aggravate the necessity of picking up amusement wherever it is to be had. Lady E. B(utler) has been quite blind more than a year. She had always high spirits, and was always, in this respect, a contrast to her graver friend whom I can well enough imagine to consenting to admit strangers for her friend’s sake, and sitting, scarcely uttering a word, intently and almost unconsciously gazing on the eye that could behold that gaze no more. Changed indeed must she be, if there be not a spirit still within her, that, if one spark had lighted it, could not have beamed with all the light of noonday life and intellect! But no more. Should we decay as these have done, may there at last, remain some proud and haughty feelings of reserve, that bars us from the stare of strangers! … But do try your utmost to let us have an opportunity of coming to a fair understanding of each other’s dispositions, &c. &c., next spring. I shall not dare to think much of it for fear of disappointment, but a fortnight will be infinitely better than nothing; and I would endeavour to return with you if possible. Surely, I shall know you some time.50

Lister imagines what the emotional impact of Lady Eleanor’s blindness must be for Ponsonby, even to the extent of seeing Butler from Ponsonby’s point of view. It’s a complicated act, in which Lister not only imagines an intrusion into the private space of the female couple (whose domestic idyll she seeks to emulate), but performs such an intrusion, becoming a spectator and (in her identification with Ponsonby) a participant in this domestic scene of fragility and vulnerability set against (and menacing) enduring same-sex love. The scene becomes a projection into her own possible old age with Sibbella or another woman companion, at risk of being exposed to the curious and perhaps mocking, gloating, vulgar or disrespectful ‘stare of strangers’.

Plaques and Projections

The first time I went to Shibden, for a study day on Lister in the summer of 2014, there was a screening of The Secret Diaries of Miss Anne Lister in the Hall in the evening, and from time to time I would glance sideways and see the film’s images of Maxine Peake as Lister and Anna Madeley as Mariana reflected in the glass of the Lister family portraits. (Or that’s how I remembered it; when I went back to Shibden, I realised the reflection must have been in the photograph of John Lister and his fellow antiquarians, because that’s the only one that has glass!) I’m very aware of how Gentleman Jack maps and projects a particular image of Lister on to Shibden, in ways more lasting than those fleeting reflections. (Angela Clare’s chapter in this volume discusses some of the more lasting material effects of those projected images).

One of the most poignant things for me about season one of Gentleman Jack was seeing Suranne Jones as Lister moving through real places that mattered in Lister’s life – Shibden, Holy Trinity Goodramgate. Both of those places are altered now by the record of Lister’s presence nailed to the walls; the Shibden plaque, in particular, must have been covered up or edited out or filmed around for the shooting of season two. A plaque fixes something in the past, but it’s also a tug along the gathers of fabric that pull together past and present. It links person and place but also separates them, holds them apart. It opens up complicated questions about the fixed and the fleeting, and about identity and time.

In his 2018 preface to the twentieth-anniversary edition of Female Masculinity, Halberstam offers the image of the butch as a ‘bodily catachresis’, something that can’t be named, or can only be named by a misnomer because the words don’t exist for it yet.51 Halberstam identifies ‘what shall hereafter be known as “the temporal paradox of the butch” – s/he is out of time and ahead of his/her time and behind the times all at once’.52 There’s a parallel here with Chris Roulston’s 2013 article about Lister as the first modern lesbian, and the way Lister’s identity moves both forwards and backwards.53 But it also made me think about Fanny Derham, in Mary Shelley’s 1835 novel Lodore – a character who is not a butch as such, though she is described as ‘more made to be loved by her own sex than by the opposite one’.54 Fanny is both closely associated with the ancient world through her reading of Greek and Latin, and someone whose story cannot yet be told by the novel but must wait for an unspecified future time. Like Alice through the looking-glass, I once suggested, the lesbian character of the 1830s can have jam tomorrow, jam yesterday, but never jam today.55 Questions of lesbian identity seem to present the difficulty, the impossibility even, of being present/being in the present/being now.

Identity categories are necessary fictions, necessary because as queer people we are still under attack. They are powerful and they’re tricksy, whether playing over the surface or affixed as a prosthesis or a monument. I talk on Skype with two friends in Canada about all this. ‘The plaque is always late from history, but it becomes history itself,’ says Nathalie Dupuis-Désormeaux, historian of eighteenth-century music and twenty-first-century composer. She’s right: the plaque promises history, the ‘real’, in a way that – say – the new statue of Anne Lister at the Piece Hall in Halifax doesn’t. It can be harder to see the plaque as just another story, another version of Lister, even if that’s all it can be. ‘The plaque is almost parasitic, like a copyright sign,’ the art historian Cristina Martinez tells me.

Cristina’s observation about the plaque as copyright sign raises questions of ownership and durability very much at odds with the literally ephemeral cardboard rainbow plaques of Heyam’s 2015 project, conceived as an act of love and affective attachment. Heyam’s introduction to Before We Were Trans notes that they avoid the term ‘reclaiming’ in the writing of trans history, because of its links with the language of capitalist ownership; they cite Gabrielle M. W. Bychowski’s observation that this sort of language fosters an idea of historical representation as ‘a scarce resource we need to fight over’.56 The language of capitalism and ownership has a particular sharpness in relation to Lister and representation, as we wait to find out what will become of Gentleman Jack in the wake of its cancellation by HBO: the #SaveGentlemanJack campaign on social media takes place amidst anxious speculation about who might pick up the rights, who has the money to back the series.

The conversational stakes about Lister and identity are higher now than they were when the television researcher told Laura Doan, ‘I’m sorry, we really need her to be a lesbian!’ There’s so much more noise, including the constant outpouring of mainstream media stories about trans issues, most of them hostile. But there’s also the amplification created by the Gentleman Jack effect: the numbers who feel a sense of identification with Anne Lister, who feel they know her, who have a sense of ownership, as fans and sometimes as researchers. What does it mean, in this context, to talk about what ‘we’ need Anne Lister to be?

Thanks to the energy unlocked by the television series, the availability of knowledge and information about Lister has increased too, opening up the world of the diaries through the WYAS transcription project. Research on Lister and her world is alive and well in the work of the Anne Lister Society, the Anne Lister Research Summit, the websites ‘Packed with Potential’ and ‘In Search of Ann Walker’, funded PhD projects, a special issue of the Journal of Lesbian Studies, and indeed the present volume. In 2014, the audience for the first Anne Lister Study Day fitted (rather tightly) into one small room at Shibden Hall; the idea of a week-long celebration of Lister that could fill Halifax Minster was unimaginable. Whatever happens with Gentleman Jack, the future of Lister Studies is something to celebrate, and so is this messy, complicated, expansive conversation about who we think she was, and why and how she matters so much.

Conclusion: No Time like the Present

It’s April 2022, and I’m back at Shibden, on the Complete Anne and Ann Coach and Walking Tour, as part of the festivities for the long-awaited Anne Lister Birthday Week. The lawn in front of the house is covered with stalls selling Gentleman Jack-themed gin, notebooks, walking sticks, art, postcards, memorabilia, and pin badges of the Shibden plaque and of the revised York plaque. There are people in Victorian costumes; I’m not sure which ones are Gentleman Jack fans doing cosplay and which ones are stallholders. A man and a woman in Victorian dress are walking around on stilts. It’s snowing, just a little, but the sun comes out while our tour group is going round the house. I’m thinking about all the other times I’ve been here, about the layers of memory and identity that line these walls. Thinking about the inaugural Anne Lister Society meeting later this week, and how the audience for my work on Lister feels so different in 2022 from the one I imagined when I started it in 2018. I’m thinking about what it means, finding the words for Anne Lister: how and where she found the words for herself; how and where we find the words for her, and how they slip or how they stay. About who ‘we’ are, too, and what we do: codebreakers, scholars, fans, critics, theorists; Civic Trusts and other affixers of plaques; screenwriters, artists; LGBTQ+ people in search of our own history. About the way these categories, too, layer and overlap. About how it’s complicated, it’s always complicated, finding the words for identity, and how the pursuit of knowledge is bound up with emotion and desire. This is not neutral territory; it never was.

Shibden in brilliant sunshine; I go out to the carriage barn again and take another picture of the doorway. Everything beyond this point is fiction.

In 2019, the diaries of Anne Lister exploded on to the screen in the form of Gentleman Jack, the BBC/HBO series starring Suranne Jones and Sophie Rundle and directed by the award-winning Sally Wainwright. Season one, which focuses on the period of Lister’s relationship with Ann Walker, with whom Lister privately sealed a union in Holy Trinity church in York, attracted six million viewers. Season two aired in April 2022 and a BBC One documentary, Gentleman Jack Changed My Life, also aired in May 2022.1 As the BBC documentary title suggests, Gentleman Jack has generated a devoted queer and lesbian fanbase, many of whom have claimed the series has transformed their lives.

Through a queer temporality framework, this chapter analyses the effects of the Lister diaries’ transition from scholarly archive to mainstream entertainment culture. Gentleman Jack has already given rise to scholarly articles and in The Gentleman Jack Effect: Lessons in Breaking Rules and Living Out Loud (2021), Janet Lea has gathered testimonies from viewers whose lives have been radically transformed by watching season one.2 Fans have also responded to the show on Twitter and Tumblr, and in 2019, Diva published a detailed article by another of the show’s early fans, Rachel Biggs, where she describes how deeply the series affected her.3 By exploring such responses to Gentleman Jack, this chapter asks what gains and losses are involved in terms of our relationship to the queer past by translating the Lister archive into the sphere of popular culture.

In A Theory of Adaptation, Linda Hutcheon argues that adaptations have always existed – at least from the classical period onwards – and that they are far from being a ‘minor and subsidiary’ genre that can never live up to the original.4 She conceptualises adaptation not as a copy, but rather as an ‘oscillation’, a ‘re-mediation’ and a form of translation between the source text and its reworking.5 As with translation, adaptation ‘has its own aura’ and creates its own resonances;6 borrowing from Walter Benjamin, Hutcheon argues that adaptation, like translation, ‘is an engagement with the original text that makes us see the text in different ways’.7 In other words, adaptation is less a copy of the original than a reinvention and a reimagining of the source text in an ever-evolving present. While adaptation can range in terms of its political register, it is always responding to its historical moment.

In this sense, adaptation speaks to queer theory’s refusal of origins, its challenge to linear temporality and its sense of the performative. Hutcheon continues: ‘Despite being temporally second, [adaptation] is both an interpretive and a creative act; it is storytelling as both rereading and rerelating.’8 Within this paradigm, adaptation is a form of queering, in that queerness has always engaged critically with secondariness, imitation and the hierarchy of origins. How, then, might this frame the encounter between adaptation as an engagement with genre and queer theory as an engagement with gender in relation to the Lister diaries and their televisual adaptation? How does the fan response to the adaptation engage with the nonconforming Lister of the historical archive?

Wainwright has herself resisted the term ‘adaptation’, which she argues suggests the smooth translation from a coherent, recognisable genre to another equally stable generic form, such as novel to film or theatre to musical. In contrast, the Lister diaries were like ‘juggling with mercury’ and were constantly slipping through her fingers.9 In the interview with Emma Donoghue for this volume, Wainwright prefers to call her work on Lister ‘a dramatisation of a real life’.10 Rather than seeing them as a fixed account, Wainwright experienced the diaries as an evolving form with unpredictable narrative threads and dead ends. The Lister diaries tell the story of a life evolving on a day-to-day basis, with no endpoint from which the work can be rendered fully coherent. The diaries simply stop when Anne Lister falls ill on her travels and dies. Therefore, Wainwright has had to engage in her own to and fro between history and story – a process that has led to the inclusion of many of the diaries’ events and anecdotes and direct transcriptions of the diaries’ language into the show – as well as creating a fictional frame to fit the demands of prime-time television.11

Gentleman Jack aligns with what Eve Ng, borrowing from Claire Monk, has termed quality ‘post-heritage’ drama, as well as with the literary concept of ‘neo-historical fiction’, coined by Katharine Harris.12 For these scholars, the more recent iterations of historical drama – both on screen and in novel form – self-consciously incorporate an aspect of the present into representations of the past, often through ‘the conspicuous use of anachronisms’,13 or by including previously unrepresented subject positions in terms of race, class, sexuality and gender. According to Harris, the goal is to ‘push beyond what we know or think is “true” about the past in order to invent new histories’.14 Both Ng and Harris invoke Sarah Waters’s queer lesbian nineteenth-century novels – several of which have been adapted for television by the BBC – as examples of post-heritage and neo-historical narratives that laid the groundwork for queer historical representation.

In televisual terms, the show that Gentleman Jack most resembles is the BBC’s production of Portrait of a Marriage (1990), a three-part mini-series about Vita Sackville-West’s 1920s affair with Violet Trefusis, based on Nigel Nicolson’s biographical account of his parents’ marriage. It stars Janet McTeer as Vita and Cathryn Harrison as Violet, and as with Gentleman Jack, it is a historically grounded lesbian narrative. Further echoing the Lister archive, Sackville-West kept a detailed diary of her affair with Violet, as well as with other lovers. Janet McTeer’s performance as Vita also parallels Suranne Jones’s as Lister in its gender nonconforming presentation and claiming of lesbian sexuality, to the point where Nigel Nicolson, who sold the rights to Portrait of a Marriage, argued that the production ‘had too much sex in it’ and that ‘[t]he affair could have been suggested much more delicately; it could be done by gesture and look, not necessarily by performance’.15

The historical distance between 1990 and 2019, when Gentleman Jack aired on BBC’s Sunday evening prime-time slot, can best be summed up by contemporary critics’ positive response to the representation of lesbian sex on screen.16 However, for an adaptation such as Portrait of a Marriage, which appeared prior to the advent of social media – Facebook having started in 2004 – it is harder to gauge the emergence of a fanbase. While Diva, the UK’s most widely circulated lesbian magazine, was founded in 1994 and played a key role in disseminating lesbian subculture, nothing resembles the rhizomatic influence of the internet. Therefore, although Portrait of a Marriage can be compared to Gentleman Jack in terms of content, it is harder to do so in terms of reception. This is reflected in the fanbase itself, which has responded to Gentleman Jack as if such lesbian televisual representation of lives from the past was the first of its kind.

Unpacking the underlying causes that have led fans to become so affectively attached to Gentleman Jack can give us certain insights into the gains and losses of adaptation and help us to understand the affective mechanisms of post-heritage drama for a queer and lesbian audience. This attachment also engages with questions of queer temporality, in that the fanbase is finding something entirely new in the old and moving backwards in time as a way of reclaiming a present that is itself saturated with a certain kind of nostalgia. As a source text, the Lister diaries are contesting the gender and sexual norms of nineteenth-century society, and Wainwright’s challenge has been to capture their already existing nonconformity for a twenty-first-century audience. How can Lister appear queer both in her time and in ours? And what is it, exactly, that the fans have been responding to with such passionate commitment?

At the same time, as Ng suggests, part of the appeal of Gentleman Jack lies as much in what is familiar as in what is ground-breaking. As a more lavish production than the original BBC Secret Diaries of Miss Anne Lister (2010), Gentleman Jack fulfils the mandate of quality drama with its ‘innovations in storytelling’, its ‘high production values’ and its ‘distinctive aesthetic qualities’.17 These elements place Gentleman Jack alongside the familiar adaptations of Jane Austen novels and create certain expectations in the viewer, ones that include ‘a certain image of England and Englishness’18 generated through what James Leggott and Julie Taddeo describe as key visual hallmarks, such as English landscaping and the representation of stately homes.19 In its exploitation of certain visual tropes that connote Englishness, such as the rolling hills of the Yorkshire landscape and scenes set in both Walker’s and Lister’s manor houses, Gentleman Jack participates in a mode of representation which Ng notes continues to depend on ‘hierarchies of class, race, and nation that have long structured the narratives of the genre’.20

The familiar therefore rubs up against the unfamiliar, in that Gentleman Jack subverts the content but not the context of quality historical drama. Indeed, one fan became attracted to the show because it was taking place around Jane Austen’s time and she knew she would be treated to the familiar props and landscapes of the Regency and early Victorian eras.21 While Ng is more critical of Gentleman Jack’s adherence to the dramatic conventions that reinforce the norms of a certain nostalgic Englishness, Sarah E. Maier and Rachel M. Friars argue that the show also challenges the conventions of historical drama by including multiple perspectives beyond Lister’s own privileged one and ‘frequent[ly] abandons Lister in favour of a wider picture of rural English life in the 1830s’.22 This also distinguishes the Gentleman Jack series from the first BBC feature adaptation of the Lister diaries, which was entirely from Lister’s perspective.

Gentleman Jack’s newness, in this sense, depends on how it takes up quality heritage television conventions as a way of subverting certain, although not all, of our expectations. The show also speaks to what Paula Blank argues is a turning away from queer history as ‘alterity’ and seeing the past ‘in terms of difference’, towards an embracing of the non-linear and what Madhavi Menon has called ‘homohistory’ and Carolyn Dinshaw has framed as ‘touching across time’.23 For Blank, the history of sexuality is less forward-moving than palimpsestic, with different models co-existing over the centuries and producing both a mode of ‘self-othering’ and a ‘queer … desire for a provisional reidentification with the past’.24 Carla Freccero has also argued for thinking about the past as a form of ‘queer spectrality’, a haunting in which ‘the past or the future presses upon us with a kind of insistence or demand, a demand to which we must somehow respond’.25 For Maier and Friars, Gentleman Jack positions Lister as ‘the connective tissue’ between ‘a lost past and present paradigm’.26 In each of these approaches to the queerly historical and the historically queer, there is a desire for both a recuperation of the queer past – defined as it has been by erasure and invisibility – and a refusal to read it in terms of progression. The queer past, these theorists argue, is a living, tactile thing that engages and simultaneously eludes us in a continuous back and forth. Furthermore, in producing an affective rather than a strictly scholarly engagement with the queer historical past, Gentleman Jack has created a fluid mode of identification that lies somewhere between fact and fiction.27

In fans’ responses, there is an implicit recognition of the precarity of queer history and of the unlikely possibility that a series tied to such an archive could exist in the first place. The diaries not only came close to being burned when their encrypted content was first decoded in the 1890s, but they also languished in various repositories for one hundred and fifty years before extracts of the coded sections were published by Helena Whitbread in 1988 and the modern world was ready to read them. The Gentleman Jack adaptation of the Lister diaries therefore parallels and undoes the scholarly project in various ways. While the role of the traditional scholar can be thought of as seeking out the truth of the past through accurate historical contextualisation and reconstruction – the past as fully footnoted – the role of the scriptwriter might be seen as adapting the past for the purposes of the present, and for an audience who may have no particular investment in history per se. In the case of Gentleman Jack, many fans will have experienced the adaptation as the original.

In this sense, Gentleman Jack has created a new kind of originating moment for the diaries themselves. Unlike the Anne Lister BBC film, Gentleman Jack covers a relatively small portion of the diaries. It is set in the year 1832, when Lister is forty-one years old and has just been rejected by her Scottish lover, Vere Hobart. At this point, Lister is looking for a more permanent companion, having had, over the past twenty years or so, a series of flirtations and more serious affairs with women from the surrounding area and during her stay in Paris in 1824. The first season’s eight episodes follow Lister’s encounter with and courtship of Ann Walker, a neighbouring heiress who, like Lister, has inherited her own property but is considerably wealthier. Walker is presented as feminine and relatively fragile, and although she is clearly in love with Lister, we see her turning down Lister’s initial proposal of ‘marriage’, the social anomaly of this being too much for Walker to envisage. The couple undergo several setbacks, including Walker’s feelings of anxiety over her attraction to Lister and subsequent breakdown. After a separation of some months, the couple are reunited in the final episode, and this time Walker is the one to bring up the marriage proposal, which both then enthusiastically commit to.

Supplementing the couple’s romance narrative, we have scenes of Lister’s family life, including her close relationship with her aunt and uncle and her sparring and competitive relationship with her sister, Marian. We see Lister dealing with her tenants, competing with the local coal baron, Mr Rawson, and developing her plans to sink her own pit. We also witness her being harassed and accosted on a country road and, of course, we see her writing her diary. As mentioned, landscape plays a key role and scenes of Yorkshire, Halifax, Shibden Hall and Crow Nest are interspersed with European travel, as in episode seven when Lister is invited to the court of the Queen of Denmark.

Through Jones’s portrayal, Lister’s gentlemanly cosmopolitanism compellingly combines visual and narrative pleasure and the viewer cannot but fully champion her courtship of Ann Walker. (See Figure 8) Yet this on-screen seduction raises interesting questions about its off-screen effects and the fans’ own experience of being seduced. Fans have reacted to the show’s familiar romance landmarks as much as to its innovative reworking of the romance trope. This has led to three broad modes of response from the fanbase: a sense of community building that connects past and present, personal narratives of self-transformation, and acute feelings of nostalgia and loss. We will unpack these affective responses in order to analyse the Gentleman Jack effect in terms of our twenty-first-century understandings of gender and sexuality.

Figure 8 Gentleman Jack, season one.

The fanbase has organised itself in different ways, with one of its most striking characteristics being lesbian community building. This has taken place largely on Facebook, coalescing around a lesbian-identified fanbase through various Facebook groups, such as the ‘Lister Sisters’ and ‘Shibden after Dark’. Fans can, of course, belong to multiple platforms depending on their needs and wants. These groups have in turn generated further adaptive mutations, such as cosplay and fanfiction. The Facebook fandom phenomenon is also what led Janet Lea to collect and publish fans’ responses in The Gentleman Jack Effect. Lea is a native of Texas and full-time writer, and her book of interviews with Gentleman Jack fans was published in September 2021, barely two years after the airing of season one. Lea frames her project through a specifically lesbian lens, shaping the connection between Jones’s Lister, Rundle’s Walker and the fanbase as a lesbian one, even though there are also non-lesbian participants and the term ‘lesbian’ never appears in the Lister diaries.

Lea’s range of participants has an impressive global reach, with fans from Kenya, New Zealand, Singapore and the Philippines, among others, encompassing sixty-nine interviews from sixteen countries, only a small selection of the six hundred responses from forty-four countries Lea received when she sent out her questionnaire on Facebook. The Gentleman Jack HBO/BBC Facebook group itself contains 10,000 members ‘of all ages from 100 different countries’.28 The use of Facebook as the interview source also signals a particular demographic, and although some fans are in their twenties, the majority are between thirty and seventy years old, which also potentially speaks to their predominant identification as lesbian rather than more recently available terms, suggesting a generational reclaiming of lesbian identity through the figure of ‘Gentleman Jack’.

Within this construction of lesbian community, fans describe moments of self-transformation and experiences of identification across time. This identification, in turn, depends on reading Lister as an authentic subject as well as a post-heritage drama lesbian heroine. Authenticity has many resonances, from designating an original document (as in the authentic Lister diaries), to being based on fact (as in the authentic historical archive), to the existential notion of living responsibly (as in living an authentic life), all of which are reflected in fans’ responses to Gentleman Jack.29 Fans talk about feelings of recognition and familiarity – ‘I felt like I was going home’30 – as well as becoming who they were supposed to be: ‘It’s all about just becoming who I really want to be, really who I have been all along.’31 One of the most moving interviews is with seventy-one-year-old Inna Clawsette (pseudonym), who had been in a heterosexual marriage for thirty years and who had always felt something was missing. She says that after watching Gentleman Jack, ‘For the first time in my life, I could just be myself … and that changed me.’32 Jones’s Lister externalises and makes visible a desire for authenticity that fans come to recognise in themselves, often for the first time. Fans also oscillate between idealising Lister and idealising the Lister–Walker couple, so that part of the fantasy of authenticity Gentleman Jack provides is relational: ‘If Anne and Ann could be themselves nearly 200 years ago, surely I could do the same in 2019.’33

Another identificatory thread that reappears between Jones’s Lister and the fans’ responses is Lister’s firm sense of self at a time when there was no clear language to support it. Paradoxically, it is Lister’s absence of identificatory language that creates a strong identification among the fans. The fact that Lister could be herself without having to name herself seems to open up opportunities for fans who have also struggled with questions of naming, whether in terms of coming out of the closet, asserting themselves in different realms such as the workplace, or resisting certain labels. In this sense, Wainwright’s representation of Lister has produced a psychological openness to new trajectories of selfhood.

This sense of newness has created an unprecedented interest in queer historical representation and in the possibilities the past can offer. Accompanying fans’ recognition of Lister’s existential authenticity – which arguably could also be applied to the characters in adaptations of Waters’s novels – is Lister’s historical authenticity. In her preface, Lea acknowledges the significance of Gentleman Jack’s tie to the historical Anne Lister: ‘Thanks to Gentleman Jack, I fell in love with a woman who had been buried for nearly two hundred years.’34 Older fans such as Kate Brown from the United States, in her mid-sixties, have described a form of temporal identification with Lister: ‘Seeing that, on TV this late in life and knowing there was a real person who experienced what we’ve experienced and she did it 200 years ago, was so validating for me.’35 In this interview, Kate is identifying her queer Baltimore youth in the 1970s with the experiences of nineteenth-century Lister, collapsing both time and place in ways that invoke Dinshaw’s notion of ‘touching across time’. The historical is subsumed under the personal as well as expanded to include past and present in a synchronous fashion. In this moment of temporal connectivity, Lister’s story simultaneously represents both her own present and Kate’s past.

For many fans, there is the added experience of unmediated spontaneity, the coming upon Lister without premeditation or intent, which has generated a feeling of authentic connection. Patience, a queer Kenyan fan who settled in the United States in part to escape the gender-normative social structures of her homeland, writes: ‘I caught a snippet of Anne Lister when she adjusts her top hat with her stick, and I remember thinking, “What is that? That looks gay.”’36 Patience is one of many fans who came upon Gentleman Jack spontaneously and who describes the effect of the series as having a direct impact on her life, from making her change her wardrobe to feeling ‘more comfortable and more self-assured’.37 Jones’s Lister created in Patience a new sense of freedom because the character herself claimed that same freedom. Most surprising in this interview is Patience’s cross-race as well as her transhistorical identification with Lister. Already positioned outside the American norm by her race – ‘everywhere I go, people see me first and foremost as black’38 – Patience seems to have found a kindred spirit in Lister’s own outlier status that combines race and sexuality. Patience, like Lister, finds herself the object of the gaze, and she admires Lister’s refusal to be defined by that normative gaze: ‘She wasn’t looking to be validated by other people. She just knew – in an environment where the culture didn’t even have words to describe who she was.’39 Here the language of existential authenticity enables both a transhistorical and transracial reading of Lister, allowing Patience to see herself in Lister across time.

The queer temporal effect of the Lister diaries – that of moving backwards in time in order to experience a new sense of the present – has a geographical as well as a historical component. One of the more detailed interviews is with Jen Carter from Maharashtra, India, and as with Patience, it documents some of the difficulties the LGBTQ+ community faces in countries lacking certain human rights protections. In India, even though homosexuality was officially decriminalised in 2018, ‘disapproval … remains high’.40 Jen’s response to the show is particularly striking in terms of India’s own complex history of British colonisation, which was at its height in Lister’s era.41 Lea explains that when Jen was a child, ‘her father had given her Jane Austen novels to read to improve her English’.42 However, in reading Pride and Prejudice, rather than being attracted to the figure of Mr Darcy, Jen wanted to be him, so that in this case, the British colonial canon is queered by its postcolonial reader and Gentleman Jack ultimately provided the perfect Darcy replacement.

As with Patience, Jen finds herself collapsing her personal history into Lister’s narrative: ‘When I saw the first episode of Gentleman Jack and Anne’s problems with Vere Hobart, I thought to myself, “Oh my God, I’m watching this – it’s my life!”’43 Importantly, the nineteenth-century constraints around gender and sexuality in Lister’s life potentially resemble those in Jen’s life more closely than for a Western viewer. While Jen’s father was extremely understanding of Jen’s sexuality, her female partner’s father threatened to kill himself if she did not go through with her arranged marriage.44 As a result, both young women attempted suicide and their relationship fell apart, a narrative that contains echoes of Ann Walker’s own breakdown in response to the constraints of nineteenth-century norms. Nine years later, Jen discovered Gentleman Jack: ‘Without Gentleman Jack I don’t know when I would have had the courage to come out.’45 Lea explains that Jen took the final step by posting her story, along with a photograph of herself, on the ‘Shibden after Dark’ website on 3 April 2020, Anne Lister’s birthday.

In these accounts, the queer lesbian viewer is rendered authentic through the converging vectors of authenticity, as feelings of familiarity, of ‘going home’ and of historical connection become part of the viewing experience. Yet the issue of authenticity is far from straightforward, as it begs the question of what is being authenticated. To begin with, fans are engaging with a mediated version of Lister, one that has been inevitably shaped and glamorised in the tradition of costume drama, even if that tradition is being queerly challenged. They are also responding to the strategic anachronisms that Wainwright has put in place. This generates a form of historical desire in which ‘the creative space of fiction’ is used ‘to resist a linear construction of time’, allowing us to ‘imagine anachronistic queer histories’.46 As Harris points out, the use of anachronism displaces conventional historical representation by layering the present on to the past and producing an affective desire for a relation across time that challenges linear models of historical authenticity.

In particular, the technique of breaking the fourth wall not only creates a synchronous bond between viewer and actor, collapsing past and present, but also produces an intimacy that echoes the genre of the diary, as if Lister were letting the viewer into her private, intimate world. As Wainwright says in her interview, Lister ‘talking to camera … was a no-brainer because it’s just like the immediacy of reading the journal’.47 In these anachronistic moments of connection, Jones’s Lister quotes directly from the diaries, returning us to the original source at the very moment when Jones in the present is displacing the Lister of the past. The breaking of the fourth wall not only reminds the viewer that they are watching a fictional performance on screen, but also brings attention to the fact of adaptation. In this sense, the figure of Lister becomes more historical – through her original words addressed directly to the viewer – and less so – through Jones’s direct gaze into the viewer’s sitting room.

Several fans, such as Michaela Dresel from New Zealand, have recorded the breaking of the fourth wall as being a defining moment: ‘The fourth wall breaks in the show when Anne Lister looks into the camera and quotes from her diaries got me hooked.’48 Katherina Oh from Singapore experienced the breaking of the fourth wall as a mode of ‘cheeky … flirting’, saying, ‘I loved when Suranne Jones broke the fourth wall. She is very cheeky when she does the raising of her eyebrows and flirting with the camera.’49 It is also significant that while Dresel refers to Anne Lister, Oh refers to Suranne Jones, so that while Dresel is inside the narrative and sustains the fiction of Lister’s presence, Oh steps outside it.

A further paradox of the felt authenticity of Lister and Walker in Gentleman Jack lies in Wainwright’s exploitation of sartorial seduction, made possible by the show’s status as a high-quality drama production. Perhaps the most idealised and fictionalised aspect of the series, and of a quality well beyond what Lister herself would have worn or been able to afford, the Gentleman Jack wardrobe adds a visual and tactile glamour to the characters that seduces the viewing public and paradoxically affirms a mode of queer authenticity. While Lister appears in black skirts and a military-inspired greatcoat, Ann Walker’s richly textured dresses allude to the eighteenth-century portraiture of a Fragonard or a Boucher. Furthermore, the gender-bending butch–femme contrast of Lister and Walker references the queer tradition of gender performativity and a queer sartorial history that spans the twentieth century, from the aristocratic Radclyffe Hall through to 1950s butch–femme working-class culture. Wainwright’s addition of Lister’s top hat – which Lister herself never wore – gives her an added masculinised authority, while also echoing the eighteenth-century drawings and caricatures of the Ladies of Llangollen, a famous female couple who eloped from Ireland to Wales in the 1780s to set up home together, and whom Lister greatly admired.

Yet Jones’s Lister also remains remarkably faithful to the descriptions in the diaries. In her diary entries, Lister frequently described both her own sense of her appearance and how others saw her, leaving us with a rich account of her clothing choices – in particular her early decision to wear only black – along with her body language and her nonconforming gender presentation. Lister was acutely aware of the effects of her physical presence and paid attention to gestures large and small, from her energetic walk to how she held her cane and twirled her watch. Jones, in turn, follows Lister’s lead, and through her glamorous androgynous wardrobe, her butch walk and her seductive presence, her Lister repeatedly contests the codes of nineteenth-century normative femininity – particularly when placed in the context of mainstream nineteenth-century heritage drama.

In terms of fans’ responses, Lister’s appeal therefore lies as much in her gender presentation as in her queer sexuality. Importantly, this has fed into Twitter debates that reflect our current struggles over identity politics. In an echo of the controversy concerning the plaques celebrating Lister and Walker’s union in Holy Trinity Church, York – where the phrase ‘gender-nonconforming’ was replaced, after protests, with ‘lesbian’ – Twitter responses to Gentleman Jack have ranged from claiming Lister as a lesbian, to seeing her as ‘the Great Butch of History’,50 to insisting she was ‘AT THE VERY LEAST GNC/non-binary’, and that ‘the argument could definitely be made that Anne would be a trans man were the resources available’.51 Other Twitter responses note the irony of opposing groups on the identity spectrum each claiming Lister for themselves, which makes Lister both central to the conversation about identity politics and a flashpoint for disagreement.52 While the overt presentism in these debates may be frustrating to some, they show how the past can invade the present and both affirm and redefine it. They also expose the extent to which the figure of Lister generates in fans a desire for identity, even as Lister herself can never be firmly identified.

One of the series’ distinctive features is how it pays close attention to Lister’s politics in a way the Secret Diaries film did not; we see Lister responding to the implications of the 1832 Reform Bill as well as her commenting on her tenants and competing with Rawson, the local coal baron. At the same time, Lister’s conservative political stance and her engagement in an aggressive form of capitalism is reconfigured through a proto-feminist lens as having the courage to stand up to the boys, as when she vies for her own coal mine. Lister’s gender nonconformity is celebrated in ways that allow her to behave like the men rather than questioning the terms of their privilege, in both her personal and her public life. Yet Wainwright, herself from a working-class background, also reminds us that Lister ‘wasn’t even landed gentry – more like the level below, yeomanry, because the Shibden estate isn’t that big, only about 400 acres’.53 Until her inheritance, Lister was also struggling for money, ‘always … borrow[ing] and wait[ing] for handouts’.54 Wainwright also suggestively gives Lister’s sister, Marian – whom Lister generally ignores and overrides – more progressive views than Lister herself – as when they are discussing the 1832 Reform Bill – subtly pointing to Lister’s investment in the political status quo. At the same time, Lister, unlike Marian, is the one being harassed and attacked on country roads on account of her gender nonconformity. In refusing conventional femininity, Lister is placing herself permanently at risk and, as Susan. S. Lanser has argued, her class allegiance and upward mobility can be read as engaging in a mode of self-protection and as a ‘compensatory conservatism … and classism’.55 Lister foregrounds what Lanser terms the ‘status risk’ of her ‘gender transgressions’ by overdetermining her class status.56

Although the majority of fans see Lister as transformative for her time and for theirs, their primary response to her remains intensely personal and privileges an affective over a political engagement with her narrative. There is a focus on Lister’s romantic individualism that is matched by an almost total silence concerning her Tory politics, her upward mobility and her landlord status. We see only the occasional critical entry, such as Tumblr’s deandykery, who writes: ‘when the class war comes [Lister] will not be spared’.57 While it is a paradox of the show that a figure who defines herself through her uniqueness and her exceptionalism has become a harbinger for contemporary community building, this also speaks to the anachronistic effect of translating the past into the present. Fans see in Lister’s refusal to remain isolated and her determination to participate in the privileges afforded her, despite her outlier status, the possibilities of a queer future. In addition, Jones’s performance arguably generates feelings of desire and/or identification that obfuscate Lister’s political conservatism. What fans fail to attend to is therefore as telling as what they highlight.

The most compelling scene for the fanbase has been the marriage proposal and the wedding day in season one’s final episode. The Lister diaries themselves, as Simon Joyce points out, ‘are full of quasi-matrimonial rituals in which she exchanges symbolic tokens with lovers as signs of “marital commitment”: rings, locks of hair, and in one striking moment, pubic hair’.58 Lister was obsessed with marriage as well as acutely aware of her exclusion from it. The marriage proposal scene takes place on top of a hill overlooking the lush Yorkshire countryside, with a subtly romantic musical score that crescendos with the sealing kiss, Walker in a powder-blue dress that echoes the sky, and Lister in her signature black overcoat studded with brass buttons. As Lister says to Walker, ‘but we’re not alive. Are we? If we’re not taking the odd risk now and again,’ a risk which is dramatised in the representation of this queer historical couple being shown in a prime-time slot.59 The marriage proposal scene was posted by the BBC as a stand-alone YouTube clip, which has received close to a million (805,650) views to date, with 1,165 comments.

In the diaries, however, there is no hilltop proposal scene and the description of the wedding day is minimal, as Lister writes on 30 March 1834: ‘At Goodramgate church at 10 35; Miss W – and I and Thomas staid [for] the sacrament … The first time I ever joined Miss W – in my prayers – I had prayed that our union might be happy – she had not thought of doing as much for me.’60 Lister had already proposed and made plans for attending a church service in lieu of a wedding ceremony as early as 14 December 1832: ‘Miss W – told me in the hut if she said “Yes” again it should be binding. It should be the same as a marriage and she would give me no cause to be jealous – made no objection to what I proposed, that is, her declaring it on the Bible & taking the sacrament with me at Shibden or Lightcliffe church.’61 This entry shows how the wedding vows were themselves in a state of instability, having been made once, then rebuffed, then reconfirmed. This highlights the complexities of enacting a public ceremony as a private event and fully believing in it as a valid speech act. While Wainwright takes on some of this hesitancy by having Walker initially refuse Lister before the final episode, this serves primarily as a build-up to the romantic hilltop scene.

Responding to this final episode, the Gentleman Jack fanbase has fully endorsed the reality of Lister marrying her beloved, and there are now lesbian marriage ceremonies being performed at Shibden Hall and many pilgrimages to Holy Trinity Church, which also boasts the aforementioned heritage plaque of the Lister–Walker union signalling the first lesbian marriage. For the fans, Lister’s marriage is a further confirmation of her authenticity, in that she is seen following her nature through this quasi-public ritual.

Yet it is precisely at the intersection of these opposing positions that the queerness of historical time comes into play. The original fiction, after all, belongs to Lister herself. It is she who was repeatedly staging and performing marital rituals with her lovers as a way of claiming social belonging and asserting her desire and her relationships in a world that was rendering them invisible. Wainwright’s response has been to foreground, rather than to mask, this fantasy element as an integral part of the Lister narrative. By following the classic courtship and romance model of conventional costume drama, yet peopling it with queer protagonists, Wainwright creates belonging and recognition across time, while arguably honouring, rather than simply fictionalising, Lister’s stated desires in her diary entries. In this sense, Wainwright gives Lister, and the fans, ‘the marriage she (and they) always wanted’.62