Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- About the Contributors

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Timeline of Twentieth-Century China

- Maps

- Part I Mao's World

- 1 Mao, Revolution, and Memory

- 2 Making Revolution in Twentieth-Century China

- 3 From Urban Radical to Rural Revolutionary: Mao From the 1920s to 1937

- 4 War, Cosmopolitanism, and Authority: Mao from 1937 to 1956

- 5 Consuming Fragments of Mao Zedong: The Chairman's Final Two Decades at the Helm

- 6 Mao and His Followers

- 7 Mao, Mao Zedong Thought, and Communist Intellectuals

- 8 Gendered Mao: Mao, Maoism, and Women

- 9 Mao the Man and Mao the Icon

- Part II Mao's Legacy

- Appendix: Selected Further Readings (Annotated)

- Index

- References

2 - Making Revolution in Twentieth-Century China

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 August 2012

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- About the Contributors

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Timeline of Twentieth-Century China

- Maps

- Part I Mao's World

- 1 Mao, Revolution, and Memory

- 2 Making Revolution in Twentieth-Century China

- 3 From Urban Radical to Rural Revolutionary: Mao From the 1920s to 1937

- 4 War, Cosmopolitanism, and Authority: Mao from 1937 to 1956

- 5 Consuming Fragments of Mao Zedong: The Chairman's Final Two Decades at the Helm

- 6 Mao and His Followers

- 7 Mao, Mao Zedong Thought, and Communist Intellectuals

- 8 Gendered Mao: Mao, Maoism, and Women

- 9 Mao the Man and Mao the Icon

- Part II Mao's Legacy

- Appendix: Selected Further Readings (Annotated)

- Index

- References

Summary

With our several thousand years of accumulated ailments, where everything is contrary to the needs of the times, if we wish to change what is unsuitable and achieve what is suitable, we must overturn things from the foundations, clean things out thoroughly. Alas! Alas! This is the task of Revolution [English in original] (what the Japanese call kakumei [Chinese: geming] …). It is the one and only way to save China today.

Liang Qichao, “Explaining ‘ge,’” 1903Why are Chinese like a sheet of loose sand? What makes them like a sheet of loose sand? It is because there is too much individual freedom. Because Chinese have too much freedom, therefore China needs a revolution.… Because we are like a sheet of loose sand, foreign imperialism has invaded, we have been oppressed by the commercial warfare of the great powers, and we have been unable to resist. If we are to resist foreign oppression in the future, we must overcome individual freedom and join together as a firm unit, just as one adds water and cement to loose gravel to produce something as solid as a rock.

Sun Yat-sen, “Three Principles of the People,” 1924Revolution is not a dinner party, or literary composition, or painting, or embroidery. It cannot be done so delicately, so gentlemanly, and so “gently, kindly, politely, plainly, and modestly.” Revolution is an insurrection, the violent action of one class overthrowing the power of another.

Mao Zedong, “Report on an Investigation of the Peasant Movement in Hunan,” 1927- Type

- Chapter

- Information

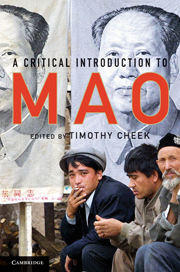

- A Critical Introduction to Mao , pp. 31 - 60Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2010

References

- 2

- Cited by