American attempts to expand its territory and population ramped up in early 1865.Footnote 1 On January 7, 1865, Waldemar Raaslöff attended a dinner hosted by the French chargé d’affaires, L. De Geoffroy, with several Washington dignitaries present including US Secretary of State William Seward. The presence of both Seward and Raaslöff was no coincidence. Authorized by President Lincoln, who had shown Raaslöff an “exceptional” amount of attention at the White House New Year’s reception five days earlier, Seward suggested that he and Raaslöff sit down before dinner in a room adjacent to the dining room to discuss a proposition that Raaslöff almost immediately thereafter relayed to the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs in a dispatch labeled “Confidential.”Footnote 2

Seward wanted to bring it to “the Danish government’s attention” that the United States “desired through purchase to attain possession of our West Indian Islands.”Footnote 3 The American proposition was motivated by the perceived need for a naval and coaling station in the Caribbean, and St. Thomas was at the top of empire-building Americans’ wish list.

In Raaslöff’s account, Seward had wanted to “put forward this Overture” for “quite some time” but had until now not been able to find “a suitable moment.”Footnote 4 The reason was an Old World conflict, now known as the Second Schleswig War, that turned out to be an important first step in Otto von Bismarck’s Grossstaatenbildung – the unification of the German states – the consequences of which had only recently become clear.Footnote 5

For Danish politicians, military personnel, and civilians alike, the conflict was devastating.Footnote 6 The war reduced Denmark’s territorial size by one-third and its population by 40 percent and thrust the country further into international Kleinstaat status – so much so that people wondered if Denmark could even survive as a nation and whether it offered economic prospects worthy of future generations’ pursuit.Footnote 7

At the peace conference in London, Danish delegates had, “in confidence” and ultimately unsuccessfully, suggested ceding the islands of St. Croix, St. Thomas, and St. John to Prussia and Austria in exchange for a redrawn border, but there were still raw emotions – and potential real political ramifications – associated with a sale.Footnote 8 The Civil War, however, had shown the need for the United States, as part of its own Grossstaatenbildung, to become a “naval power,” and, now that the peace agreement between “Denmark and the German great powers had taken effect,” Seward trusted that negotiations could be conducted with “the greatest possible delicacy and discretion.”Footnote 9

Still, the Schleswig question complicated American imperial pursuits. As Erik Overgaard Pedersen has shown, Denmark’s foreign policy after 1864 was primary determined by attempts to regain at least part of Schleswig and minimize any further loss of territory or population. To affect such an outcome, support from France and Great Britain – who were wary of the United States extending its strategic and military position into the Caribbean – was crucial. On the other hand, a successful sale of the Danish West Indies would bolster the depleted Danish treasury while also resolving a complicated – and by 1865 no longer economically beneficial – colonial relationship in a far-away region.Footnote 10

These intricate international relationships would, along with the American domestic tension over citizenship questions, determine the negotiations for the next five years. In the end, despite a treaty signed by both American and Danish diplomats, the United States, in Seward’s words, chose “dollars” over “dominion” as the Senate never ratified the agreement and thereby revealed the limits of small state diplomacy as Danish politicians had little, if any, leverage.Footnote 11

Initially, however, it was Danish fear related to the threshold principle that hampered the negotiations.Footnote 12 Raaslöff, for example, described the thought of losing the West Indian Islands as “too painful for me to entertain” and sensed that a sale “would be contrary” to King Christian IX’s “feelings.”Footnote 13 The origins of such “painful” thoughts, and Schleswig’s future importance, were found in an attempt to consolidate the Danish Kingdom more clearly along ethnic and linguistic lines.Footnote 14 On November 13, 1863, the Danish parliament passed the so-called November Constitution aiming to divide Schleswig from the mainly German-speaking Holstein.Footnote 15 This move, however, was seized upon by leading politicians within the German Federation, the Prussian minister-president Otto von Bismarck among them, as a breach of the London Treaty following the First Schleswig War. Within months, war between Denmark and Prussia – the former aided by a contingent of Swedes, Norwegians, and Finns, the latter allied with Austria – broke out.

These Old World developments were followed closely in America by politicians, diplomats, and Scandinavian immigrants alike.Footnote 16 Emigranten, Fædrelandet, and Hemlandet ran weekly updates, and in New York Scandinavian leaders and diplomats, led in part by Waldemar Raaslöff, organized a fundraising drive.Footnote 17 The war found its decisive military moments at the battles of Dybböl and Als. After a two-month-long siege, numerically superior Prussian troops overran the Danish ramparts at Dybböl on April 18, 1864, and by late June seized all of mainland Jutland. As noted, the war’s consequences were deeply felt in Northern Europe.Footnote 18 Not only had Denmark lost sizable territory and population to emerging great powers in Europe, the post-war years also saw Denmark, Sweden, and Norway lose population to emigration, in part due to Seward’s promotion of the Homestead Act.

While the Second Schleswig War for some months made it more difficult for Scandinavians to emigrate to North America, as passage between Denmark and northern Germany (e.g. Hamburg) for a period was not possible, the end of the war led a number of Scandinavian immigrants west. For Swedish, Norwegian, and Danish citizens returning home with military experience in the summer of 1864, the United States became an increasingly attractive place to resume a military career.

Figure 10.1 The mill at Dybböl came to symbolize the military defeat in 1864 for generations of Danes as the battlefield and surrounding territory was annexed by the emerging German Grossstaat.

On September 16, 1864, American consul William W. Thomas Jr. wrote from the Kingdom of Sweden and Norway that Swedish volunteers from the war of 1864 were arriving “in squads of five, ten, and twenty” and that all heartily wished to “go to America and join the forces of the Union.”Footnote 19 Thomas personally arranged for these soldiers’ travel by raising money and working out arrangements with captains in Hamburg. While acknowledging that “as consul I can have nothing to do with enlisting soldiers,” Thomas nevertheless wrote with pride that he had “forwarded over thirty [Swedish veterans] this week” whose fare had been paid by “good friend[s] in America, including the Consul himself.”Footnote 20 Thus, Thomas knowingly leveraged Swedish veterans’ post-war economic anxiety to add military manpower in opposition to the interest of Swedish authorities but claimed to provide a valuable opportunity that the veterans’ themselves sought.Footnote 21

Thomas’ example was far from singular. While recruitment in Germany was officially illegal, more than 1,000 men in Hamburg were enlisted through Boston-based agents in the latter years of the war, and British diplomats raised numerous complaints of “fraudulent enlistment” as well.Footnote 22

Additionally, as described in Emigranten, the German Press reported that “several” Danish officers, some of whom may have been living south of the recently redrawn Danish-German border, were about to leave for America from Hamburg and Bremen in December 1864. According to an article in Hamburg Nachrichten (Hamburg Intelligencer), eleven war veterans had arrived in the port city and “a large number of comrades were expected to follow.”Footnote 23

These Scandinavian war veterans were, in part, looking for opportunities to use their military experience in the American Civil War, but the Homestead Act, which had taken effect in 1863, also became an increasingly powerful pull factor. After 1864, Scandinavian immigrants, with limited opportunity for upward social mobility in the Old World, thereby played into Seward’s Homestead vision of European migration adding to the nation’s population, pool of recruits, and territory through the Confederacy’s defeat and western expansion when Old World conditions became too desperate.Footnote 24

The Scandinavians who did arrive expressed pride in the nation they had now become part. “At the present time America has a great army and perhaps more than all of Europe’s armies,” wrote Norwegian-born Ole Jakobsen Berg in January 1865, adding that no country could measure up to the United States. Yet how the newly adopted nation would maintain this appeal and simultaneously reconstruct itself, with the South’s added population and territory, after four years of Civil War remained an open question. To Seward, part of the answer was continued expansion.

Despite being a small state diplomat, Raaslöff had cultivated a fruitful relationship with William Seward stretching back to at least 1861, when the two agreed to explore colonization of “now emancipated negroes” in the Caribbean.Footnote 25 The mutual trust made Seward confident that he could count on Raaslöff’s “discretion” when he opened negotiations for the purchase of St. Thomas, St. Croix, and St. John on January 7, 1865, and Raaslöff on the other hand reported that Seward was “entirely serious” and acted on behalf of the president.Footnote 26 According to Raslöff’s report of the meeting, Seward stated that “the United States naturally would not want to see” the islands fall into the hands of “another power” and promised the “most loyal and most friendly” negotiating position toward Denmark.Footnote 27 If Seward’s proposal did indeed give “occasion for negotiations,” the American secretary of state promised that they would be conducted in the “most ‘generous,’ ‘chivalrous’ and ‘delicate’ manner.”Footnote 28

The meeting sparked high-level negotiations between Seward’s Department of State and the Danish government often represented by Raaslöff. Despite the Danish king’s hesitancy, which initially put negotiations on hold, Raaslöff was notified by the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs on February 24, 1865, that the country’s “financial and political position” necessitated a thorough consideration of the American proposal and that “on an occasion such as this, personal feelings should not be the sole factor.”Footnote 29

Yet the negotiations were derailed – as were so many other lives and policy decisions – on April 14, 1865, by John Wilkes Booth’s fateful shot in Ford’s Theater and Lewis Powell’s knife-wielding attack on Seward.Footnote 30 The following day, Raaslöff received a melancholic message from Acting Secretary of State William Hunter, who had the “great misfortune” to inform him that:

The President of the United States was shot with a pistol last night while attending a theatre in this City, and expired this morning from the effects of the wound at about the same time an attempt was made to assassinate the Secretary of State[,] which though it fortunately failed, left him severely, but it is hoped not dangerously wounded, with a Knife or Dagger. Mr. F. W. Seward was also struck on the head with a heavy weapon and is in a critical condition from the effect of the blows. Pursuant to the provision of the Constitution of the United States Andrew Johnson, the Vice President, has formally assumed the functions of President.Footnote 31

Raaslöff, who responded to Hunter’s news with “deep and sincere grief,” on April 22, 1865, reported home to the Danish government that a planned meeting with the secretary of state would now be postponed indefinitely.Footnote 32

It was soon clear that the assassination of President Lincoln, who had recently laid out a vision of reconstruction with “malice towards none” and a personal preference for Black men’s suffrage, had far-reaching consequences inside and outside American borders.Footnote 33 Lincoln’s successor, Andrew Johnson, shared the late president’s homestead advocacy and vision of expansion into the Caribbean through purchase of “the Virgin Islands,” but in his opposition to freedpeople’s landownership and equality he helped legitimize ideas of Black inferiority and helped exacerbate splits in the Republican Party.Footnote 34 Such nationwide debates over expansion and equality also rippled through Scandinavian-American communities.

Cannons boomed in celebration across the South toward the end of the Civil War. In Little Rock, Arkansas, Nels Knutson described a 100-cannon tribute to General Philip Sheridan’s victory in the Shenandoah Valley in October 1864. In Alabama, Christian Christensen noted a 100-gun salute to celebrate the victory over Lee’s army in April 1865 and a 200-gun salute when Mobile fell.Footnote 1 In New Orleans, Elers Koch, who had been forced to serve in the Confederate cavalry for part of the war, described a “great illumination” and salute “on account of the surrender” and added: “I feel like I want to Hurrah all the time, I feel so elated by the Federal success.”Footnote 2

But euphoria soon turned to sorrow. With news of Lincoln’s death, troops such as the 54th Massachusetts in Charleston, South Carolina, “lowered flags, fired guns, tolled bells,” and a “silent gloom” fell over the Union Army’s encampments while military and civilian buildings were draped in black.Footnote 3 As far north as New Denmark, Wisconsin, Fritz Rasmussen’s father noted the “great general mourning” associated with the “murder,” and his son-in-law, Celius Christiansen, years later described a similar experience in Missouri.Footnote 4 “Never will I forget the impression, I got, by seeing the great city, St. Louis, in a mourning garb,” Christiansen wrote: “Everything was draped with black cloth even down from all the church spires. Thousands of dollars had been spent in this city alone to express the people’s deep mourning of the president.”Footnote 5

The Confederate capitulations, Lincoln’s assassination, and the attempt at Secretary Seward’s life, along with all the other “events over the last month,” led to a sense at Emigranten that April 1865 had surpassed “everything that has thus far taken place in the continent’s history.”Footnote 6 With Lincoln’s assassination, thoughts of retribution, for a moment, supplanted thoughts of reconciliation.Footnote 7 Writing from Nashville, Tennessee, in late April or early May, Norwegian-born Julius Steenson struggled to find the words to describe his feeling of “horror” and “vengeance” toward “the assassin Booth” in a letter to his cousin Mary.Footnote 8 Steenson was glad that the “murderer” had been caught but sorry that Booth was killed in the process, feeling that “to die so quick was not enough punishment for such an act as to kill that man of so great private life and public worth.”Footnote 9

Retribution was also on Edward Rasmussen’s mind: “You have probably heard that they have caught the traitor Jeff. Davis and I hope that before you receive these lines that he is strung up in a gallow as high as Haman’s,” Rasmussen noted with an Old Testament reference, in a letter to his son Fritz.Footnote 10 In a similar vein, the Swedish-born colonel Hans Mattson, stationed in Jacksonport, Arkansas, wrote to his wife that several “persons were shot dead by soldiers at Little Rock for rejoycing [sic] over Lincoln[’]s murder – it served them right.”Footnote 11

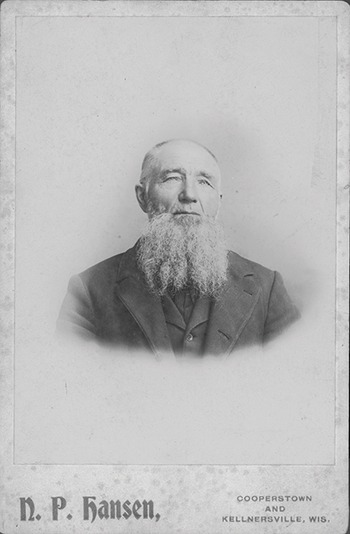

Figure 11.1 Hans Mattson became one of the best-known Swedish-American Civil War officers and later one of the best-known Scandinavian-born politicians in the United States.

Mattson’s letter alluded to the simmering tension and the potential for violence between former Confederates and the Union Army tasked, in part, with ensuring public safety, not least that of freedpeople. Guerrilla attacks, robberies, Union soldiers’ own looting, and attacks on the formerly enslaved at times found their way into accounts, demonstrating both prejudice and empathy toward freedpeople among Scandinavian soldiers.

Maintaining law and order proved difficult in numerous instances during this early part of Reconstruction. Norwegian-born Ole Stedje, writing from Duvall’s Bluff, Arkansas in March 1865, noted the importance of winning over the local population in a larger effort against paramilitary bands, and Danish-born Wilhelm Wermuth described “violence so common here that there is not much to say about it,” after falling victim to guerrillas in Kansas.Footnote 12

Fritz Rasmussen, who spent the majority of his one-year service in Alabama, also witnessed instances in which tension between white southerners and freedmen likely turned violent. Describing a boat being loaded with confiscated rebel weapons, Rasmussen on August 2, 1865, saw one gun go off and hit “a negro in one side of the abdomen,” tearing a “hideous” hole to the intestines.Footnote 13 “Several people thought that the carpenter aboard had shot him,” Rasmussen noted, “as it was known that they had exchanged words.”Footnote 14

While Rasmussen did not specifically note the carpenter’s ethnicity, the fact that he, unlike the victim, was not described as “a negro” possibly makes it an instance of a white laborer shooting a Black man. If so, it was part of a larger pattern during the early part of reconstruction. As Carole Emberton has noted, “the violence recorded by the [Freedmen’s] Bureau attests to both its pervasiveness in postwar society as well as the indeterminacy of power relations in everyday life.”Footnote 15 In Missouri, Rasmussen’s brother-in-law Celius Christiansen contemplated violence and the consequences of slavery when he arrived at “Væverly” (Waverly); in his memoirs he recounted the aftermath of a guerrilla attack in 1865:

They had so little respect for the military that they, in broad daylight a Sunday afternoon, attacked a plantation close to town. Here they shot three negroes, whereof one died immediately, and the two others survived by pretending to be dead. I spoke to one of them who had three bullets in his head and someone had knocked his teeth in, so it was horrible to watch. That such an outrageous attack frightened the black population is quite natural and I remember that I felt great compassion with them by hearing their lamentations and seeing their misery and sadness.Footnote 16

Christiansen claimed the attack was committed by the famed outlaw brothers Frank and Jesse James, who had returned to their family farm in nearby Clay County, Missouri, in late 1865, but the chronology does not quite add up, as the 50th Wisconsin left Waverly in the summer.Footnote 17 It is, however, possible that Christiansen did witness the aftermath of an attack by bushwackers in the summer of 1865, as Waverly was situated in a “triangle of counties” where the anti-Unionist – and by extension anti-Black – sentiment, according to T. J. Stiles, “was fiercest.”Footnote 18

Importantly, Christiansen’s memoir also revealed a certain ambivalence about race and ethnicity in the post-war moment, as he expressed sympathy for “the poor black slaves” who suffered in bondage, disdained the many shabby slave huts he encountered, and applauded abolition of “the gruesome slavery” but also, to an extent, admired ex-confederates and supported American Indians’ removal.Footnote 19 Christiansen became “intimate friends” with an alleged former bushwacker and later praised a victory against Lakota people that opened up “large expanses of the best lands.”Footnote 20

Christiansen’s story exemplifies the complexities on the ground in the post-war South but indicates Scandinavian immigrants’ lack of postbellum reflection regarding Native people and freedpeople’s precariousness in the face of violence as well. Yet, even as Scandinavian-born soldiers often abhorred violence against freedpeople, few examples exist of them proactively fighting for Black citizenship, voting rights, and equality in the Civil War’s immediate aftermath.

War service in the South helped transform some perceptions of race among Scandinavian-born soldiers, as was the case for a correspondent who wrote to Hemlandet in October 1863 from Helena, Arkansas, to express his admiration of the service performed by a “Corps d’Afrique.”Footnote 21 Moreover, in Emigranten on April 25, 1864, Ole Stedje from the Army of the Cumberland wrote: “When one, as we do, move about down here for a longer period of time, and can see all of slavery’s conditions revealed, the thought forces itself upon one that even if one previously was a stiff Democrat, slavery has been the South’s most depraved institution.”Footnote 22

Christian Christensen’s wartime interaction with future freedpeople likewise revealed racial attitudes that set him apart. According to an 1865 letter from fellow officer and fervent abolitionist Brigadier General John Wolcott Phelps, Christensen’s “bearing towards the negro race was peculiarly gratifying” and “indicative of a generous heart and an enlarged and liberal understanding.”Footnote 23 To Fritz Rasmussen, military service underlined the immorality of slavery. In his diary post from July 23, 1865, Rasmussen wrote about the wealthy planters’ “arrogance” that led to war and added his thoughts on abolition:

What joy I felt the other day when “the provisional Governors Proclamation” was brought into the tent and Ed. Daskam, among other, read: “There is no more a slave in Alabama.” Yes, what indignation I feel every time something catches my eye related to the depravity of slavery. This afternoon I went to church in a big negro church, as it is called here, and precious and beloved, relatives and friends, the feelings I suffered or went through there are impossible for me to describe.Footnote 24

Expression of admiration and sympathy for the formerly enslaved, however, seldom translated into concrete action or enthusiasm when Scandinavian immigrants later debated or acted on the question of freedpeople’s civil rights. For every Stedje, Christensen, and Rasmussen, there were Danielsons, Winslöws, and Hegs who used the phrase “niggers” even while expressing some support of abolitionism.Footnote 25

Important clues to understanding the ambiguity of equality expressed in the soldiers’ letters, diaries, and memoirs are found in the Scandinavian-American press. The issue of land redistribution was for example broached in Emigranten on April 10, 1865, when General William Sherman’s Special Field Order No. 15 was described in positive, yet prejudiced, terms:Footnote 26

At a previous occasion, “Emigraten” has reported on an order from General Sherman which concerns setting aside islands and a part of the coast line in South Carolina, Georgia and Florida for the freed slaves’ disposal. There they could build a home, manage cotton growth, agriculture or all together such operations as they from their youth are trained to do and understand … The government has chosen a good and completely comprehensive plan to provide for “Sambo” and his colored family … It is hereby demonstrated that the Negro can provide for himself as soon as he is put to work and this is all one can require.Footnote 27

The expectation of freedpeople providing for themselves through agricultural work as soon as possible was a common refrain in the Scandinavian-American press. Still, when President Andrew Johnson by September 1865 directed the commissioner of the Freedmen’s Bureau, General Oliver O. Howard, in Eric Foner’s words, to order “the restoration to pardoned owners of all land except the small amount that had already been sold under a court decree,” the issue was no longer at the forefront of Scandinavian immigrant newspapers, whose pages were filled with local election coverage with almost no discussion of racial issues.Footnote 28

In November 1865, for example, “Wisconsin was among the first of fifteen states and territories where white men had the opportunity to enfranchise their black counterparts” and, as Alison Clark Efford reminds us, “declined to do so.”Footnote 29 Scandinavian immigrants, who often professed to have come to the United States because of liberty and equality, were likely on the side that declined.

Despite the opportunity to advocate for extending the right to vote (with its implied connection to citizenship), no letters to the editor appeared in the main Scandinavian newspapers, and discussions of race were also almost completely absent from the editorial page. On the eve of the election, Emigranten did, however, in a longer piece manage to squeeze in one sentence criticizing the Democratic gubernatorial candidate’s complete opposition to freedpeople’s rights when it pointed out that “Union men grant each other the right to be for or against giving the Negroes the vote in Wisconsin,” but the Scandinavian paper did not elaborate on its own position.Footnote 30 Fædrelandet also spent very little ink on the election but was a little clearer than Emigranten on November 16 when it noted the Union Party’s “splendid victory” and also the “rejection” of the suffrage proposal.Footnote 31 On the question of Black men’s right to vote, Fædrelandet added:

The time is probably not right either to answer this question in the affirmative, but we hope that the time is not distant when any friend of freedom and human rights will say: “now the time has come, now the negro is worthy of admittance as citizen.”Footnote 32

Though it is difficult to assess opinions on the ground in Scandinavian enclaves, Susannah Ural’s point that “editors could not stay in business if they failed to address the interest of their communities” does at the very least indicate a split even among Republican-leaning Scandinavian voters on the Black suffrage question.Footnote 33 Among German immigrants in Wisconsin, the split was likely even more pronounced. As Efford has demonstrated, “German Republican leaders in Wisconsin were firm on suffrage,” but the German leaders’ position differed from the position of most German-born “Wisconsinites, the majority of whom voted Democratic,” and it was also more forward-thinking than was the case for Scandinavian-born editors.Footnote 34

In a Republican Party that, according to Richard White’s assessment, was the party of “nationalism, economic improvement, personal independence, and more tentatively, universal rights,” the Scandinavian press generally sided with the (white) nationalism and economic improvement faction.Footnote 35 The question of citizenship, and by extension suffrage, was central to the struggle among Republican factions, and the central arena was Washington, DC.

As such, Lyman Trumbull, still chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, was questioned about citizenship and skin color in early 1866. Would the proposed 14th amendment guarantee citizenship for “persons born in the United States … without distinction of color?” Democratic Senator James Guthrie of Kentucky and Republican Senator Jacob Howard of Michigan asked.Footnote 36 The answer, Trumbull explained, was yes and no: mostly “no” for Indians (“We deal with them by treaty”), but mostly “yes” for everyone else.Footnote 37 Trumbull’s answer, which included “the children of Chinese and Gypsies” as potential citizens, surprised Republican Senator Edgar Cowan, who argued that an immigration influx from China could “overwhelm our race and wrest from them the dominion of that country.”Footnote 38

The use of the phrases “our race” and “dominion of that country” was telling, and Cowan in his next comment denied that children of Chinese immigrants could be considered citizens as of right now. This led Trumbull to ask, is “not the child born in this country of German parents a citizen?” To which Cowan replied: “The children of German parents are citizens; but Germans are not Chinese; Germans are not Australians, nor Hottentots, nor anything of the kind. That is the fallacy of his argument.”Footnote 39 To this reply, Trumbull simply stated, “The law makes no such distinction.”Footnote 40

Scandinavians also were not Germans, but in the discussion over citizenship, the Norwegian, Swedish, and Danish ethnic elite actually considered themselves superior to competing European ethnic group such as the Germans – and even more so in relation to nonwhites. As an example, a mixed news and opinion piece, likely penned by Solberg, in Emigranten on August 13, 1866, asked: “Who is white?”

The question, the writer pointed out, had caused considerable trouble in Michigan, as it was “suspected” that someone “having a mix of ‘black’ blood in his veins,” had voted.Footnote 41 Yet, the blood, according to the Emigranten editor, distinguished “us free Americans” from other groups:

African blood is “black,” European “white” and if a man wants to be somebody, there cannot be a trace of “black” blood in his veins. Enthusiastic about the idea about freedom and equality, we Norsemen did indeed protest slavery’s monstrous motto that “the Black man has no rights which the white man is bound to respect,” but what was simply meant by this protest was the right to not be a slave against one’s will.Footnote 42

In short, while the editor explicitly distanced himself – and Scandinavians more broadly – from the wording of the 1857 Dred Scott decision in a case revolving around a Black man’s freedom from bondage, the ideas behind the decision, that Black people where inherently inferior and could neither be equal nor citizens seemed acceptable.Footnote 43 In terms of political citizenship, only “fullblooded” Europeans, who “stood as high above anyone with mixed blood in the veins as the pure thoroughbred over the simple draft animal,” should have the right to vote in the United States, Emigranten argued.Footnote 44

Thus, even as Scandinavian immigrants professed their admiration for American ideals and wrote home about “the principle of equality” being “completely recognized and entirely implemented,” as one Norwegian correspondent did to an Old World newspaper on September 28, 1866, the principle of equality was still far from recognized or implemented on the question of suffrage extended to nonwhites and, as we shall see, women.Footnote 45

In rural Scandinavian immigrant enclaves, gender roles by 1865 were still very much tied to Old World perceptions and practices. As Jon Gjerde has argued, paternalist European family patterns “based on Scripture and ‘correct’ behavior” often “informed the relationship between husband and wife,” as well as that “between parent and child.”Footnote 46

Yet returning veterans, some physically or mentally ill, came home to communities where women had run the households for months if not years. Thus, the Civil War’s end ushered in a transition period where traditional roles within and outside the home by necessity were in flux and at least implicitly forced community members to reassess and renegotiate gender roles.

For most of 1865, Fritz Rasmussen’s wife Sidsel worked so hard at the farm in New Denmark, while raising three little girls, that she could hardly find time or energy to write in the evening. Still, Sidsel sent regular letters to her husband.Footnote 47 On June 12, Sidsel wrote about the difficulty of collecting her thoughts given the demands of childcare but still dutifully described events on the farm and also engaged Fritz Rasmussen’s apparent criticism (his letter to her has not been preserved) that she had not overseen farm work closely enough.Footnote 48

Ten days later, Sidsel noted that Union soldiers were slowly starting to return (“two Germans came the other day”) and added that “Olsen and Christen ‘Carpenter’ would follow in a few days.”Footnote 49 These returning soldiers gave reason for optimism that Fritz Rasmussen also would soon return home, and Sidsel therefore decided, contrary to her husband’s request, that it did not make sense to send the money south.Footnote 50

Sidsel’s letters in the summer of 1865 expressed hope that his return would lead to a happy long-term family life; they also revealed the amount of labor she was doing. “It is high time to get out and milk and do the chores,” Sidsel concluded her June 22 letter; her letter of June 29 noted that it was difficult to write as “little Gusta also wants to join.”Footnote 51

By July 23, Rasmus “Sailor” as well as Anton and Johan Hartman had returned home; added Sidsel: “I should so wish that you could also come tiptoeing home to us.”Footnote 52 As the soldiers started returning, however, it was also clear to the community’s civilians that the veterans often were physically weakened. Norwegian-born John Arvesen, who had served in the 50th Wisconsin Infantry, “came back from the hospital in Madison” so ill that the doctor, according to Fritz’s father, did not expect him to live.Footnote 53 Arvesen died shortly thereafter; and Marcus Pedersen, who was drafted in the fall of 1864 with Fritz Rasmussen, also passed away soon after returning home to New Denmark.Footnote 54

With Pedersen’s death, Sidsel’s thoughts immediately turned to his widow. “I can hardly hold back the tears at the moment thinking of what Markus’ poor wife has gone through,” Sidsel wrote. “[He] was lying there in the greatest misery imaginable. He had almost decayed before he let go of this life.”Footnote 55

And in New Denmark the story of illness, exacerbated by persistent outbreaks of smallpox, continued throughout the summer and regularly left women the healthiest and strongest in the household. “Most of the enlisted have been ill, Cillius and Rasmus ‘Carpenter’ have been very sick but are now improving,” Sidsel wrote.Footnote 56 Fritz’s brother James added on August 27 that “cousin Rasmus” had come home with the “fever,” which was a common sight: “most of the discharged soldiers become ill or indisposed when they return.”Footnote 57 James attributed the health issues to the changing climate, but Fritz in his reply on September 14 seemingly also alluded to a mental health aspect: “I am not surprised that the returning soldiers are a little out of balance when they return home. I myself expect my share of indisposition if I ever see the home again,” Rasmussen wrote from Alabama.Footnote 58

Yet, just as Sidsel had hoped, her husband came home and surprised the family on Tuesday, October 24, 1865. “About 9 Oclock P.M. I tapped at my own door & immediately fondly & reverentially greeted my dear & beloved Wife,” Rasmussen wrote.Footnote 59 Seeing his children was equally powerful. “The emotions I felt of hearing my little Daughter prattling Papa! Papa!! were even nearer to overcome [my] selfpos[s]ession.”Footnote 60 Such a meeting was unforgettable. “Home! Home! Home!! Home!!!” he wrote and noted that in this exact moment he could have died a happy man.Footnote 61 But instead of death, Fritz’s return brought life. A little over nine months later, July 19, 1866, the couple’s fourth child and first son, Edwin, arrived and filled Rasmussen’s diary with bliss:

Happy day for Me! A Day that I have long anticipated with sore forebodings; but, Thanks thanks! to Thee oh Lord! For undeserved mercy & blessings! … I have this day been blessed with a new Subject for my own individual family-circle; and, not that one Sex; would [not] be as Kindly received as another, I do declare, that, it did turn a variety this time, from the usual run, so that the first I know of, was the exclamation from both of the old Ladies: “Oh! It is a – – – Boy! A Boy!!” Yes! It is a Boy! My Boy.Footnote 62

Yet the joy of homecoming was mixed with the complexity of homecoming. Rasmussen’s delight at finding the family in good health, the farm in good condition, and the harvest better than expected turned to concern toward the end of 1865. Sidsel had for some time not been feeling well, and her illness seemed “more and more suspicious.”Footnote 63 The recently returned veteran had hoped that the couple’s wartime separation would have helped their relationship, but on December 22, 1865, likely not knowing about Sidsel’s pregnancy and the significant discomfort it caused her, he wrote that he felt his wife’s “coolness” toward him acutely.Footnote 64

Sidsel was so ill that for several days leading up to Christmas she could not get out of bed to take care of the household chores her husband expected. Childcare thus became one of Fritz’s responsibilities, a task he found boring and felt ill-equipped to carry out (“I am no ‘woman-man’ [qvindeman],” Rasmussen had written in 1864).Footnote 65 In his own words, proof of Rasmussen’s lack of domestic ability came on Christmas morning, when it turned out that he had forgotten to prepare gifts for his three daughters and thereby significantly disappointed the family’s youngest.Footnote 66

During his military service, Rasmussen harbored “elysian dreams” about what life would be like if only he survived, but the realities of marriage, fatherhood, and community life proved harder to handle.Footnote 67 In addition to the economy, family demands created tension in Fritz and Sidsel’s marriage. Sidsel experienced physical discomfort during pregnancies to such an extent that, when she found out in late 1862 that she was pregnant with the couple’s third child, she was “bathed in tears” and, to her husband’s dismay, attempted to “contradict nature” by requesting a remedy for an abortion.Footnote 68

A baby girl, Augusta, arrived on August 11, 1863, but the tension between Fritz and Sidsel during the pregnancy, and the continued domestic and reproductive expectations put on Sidsel, spoke to women’s roles in rural Scandinavian enclaves and larger society. “The family itself,” as Stephanie McCurry reminds us, was a “realm of governance.”Footnote 69 Despite Fritz Rasmussen’s assertion that “one Sex” would be “as Kindly received as another,” boys were valued more than girls from birth, as evidenced by Rasmussen’s description of his first son’s arrival (“A Boy!! Yes! It is a Boy! My Boy”), in contrast to the more measured acknowledgment of the arrival of his first child, Rasmine, on November 29, 1858 (“a beautiful little girl and daughter”).Footnote 70 Twenty years and seven children later, Sidsel would eventually lose her life at the age of forty, a few weeks after having given birth to a baby boy, Sidselius, on April 4, 1878 (“that it is a boy is for us doubly satisfactory,” Fritz Rasmussen noted immediately after the baby’s arrival).Footnote 71

Before then, despite their frequent expressions of affection for each other, Rasmussen also regularly described heated arguments with Sidsel. On July 26, 1867, after a conflict over farm work, in which Fritz had declined Sidsel’s offer to help as he thought it would be too hard on her, she remarked, “That is a new thing, if you would always exempt me so, it would be pleasant!”Footnote 72 The exchange, which according to Fritz was also tied to Sidsel’s desire for more material comfort, and the fact that Sidsel had demonstrably started working in the field anyway led Fritz to dejectedly write:

Such is the world: Some living through it easy and comfortable; others simi-slaves [sic], in indigency and want; Some basking in Sublimest loves blisfullness [sic] and content, others in a Simi-hell [sic]. But where is the alternative, when providence or predestination so ordains … if it was not, that it [writing] seemingly helps to dispell my troubled thoughts … then, I say, that I should rather fling both paper and pen into the fire – and, often in mind, to follow myself.Footnote 73

Sidsel’s insistence on grasping moments of autonomy, possibly shaped in part by her wartime experience of running the farm and resistance to Fritz’s insistence that she limit work outside the home, challenged the Northern European Old World gender roles that many rural Scandinavians and also Germans in America modeled their households after. As Efford has noted, the “dominant constructions of ethnicity suggested that women’s rights would undermine the immigrant community and endanger pluralism,” and the “fear that politics would distract women from their domestic role” was prevalent.Footnote 74 Similar tropes about women’s sole fitness for domestic duties appeared regularly in the Scandinavian-American press. For example, Hemlandet on May 15, 1866, ran a piece under the title “On the Woman’s Emancipation” that cautioned against a movement for expanded women’s rights in Sweden.Footnote 75 In the following years, the Scandinavian press regularly critiqued women who wanted to “forsake family life for public life,” and one anonymous correspondent compared women to hens, insinuating that they had lighter brains and were happiest when they “hurried home to bring order to the household.”Footnote 76

These articles pointed to the uneasy relationship that existed between Scandinavian immigrants’ profession of liberty and equality and issues of economic inequality, gender, and race in postwar American society.Footnote 77 Even the few articles and editorials that did advocate for women’s rights revealed fault lines of class and race when attempting to bridge gender divides. For example, Skandinaven ran a piece on October 5, 1869, that argued women were just as well suited to voting as men and that they understood political issues as well as “the masses of white voters,” given that most white women, the writer implied, “in intellectual and moral advancement stand above Negroes, Indians, and the Chinese.”Footnote 78

In short, Scandinavian editors’ positions, as well as the letter writers they admitted into their newspapers, were generally conservative on questions of racial and gender equality. The Scandinavian-American press leaned more toward a return to a perceived economic and rural antebellum stability, now that abolition had been achieved, rather than using the Civil War as a stepping stone to reinventing and extending citizenship rights to freedpeople, Native people, and women.

Such positions became increasingly apparent as Scandinavian-born leaders enthusiastically embraced the Republican Party’s laissez-faire arguments in the post-war moment and simultaneously silenced voices arguing for a broader definition of equality within American borders.

When Hans Mattson rose to speak to fellow Civil War veterans in St. Paul on March 6, 1889, the former officer emphasized the apparent ease with which white Union men and their white rebel counterparts had agreed to “bury the past” in order to shake hands over the war’s “bloody chasm” and together work for a better future.

As commander of a Union force in Arkansas, Mattson was tasked with protecting the local population, overseeing Confederate soldiers’ parole, and enabling the transition to freedom for thousands of formerly enslaved in the state.Footnote 1 However, the Swedish-born officer, who in 1861 defined the Civil War as a conflict between “freedom and tyranny,” twenty-four years later spent little energy discussing the plight of freedpeople and instead underlined how the federal military from the beginning had encouraged a laissez-faire approach to economic reconstruction in a region devastated by four years of war.Footnote 2

“You must like free and independent citizens, place yourself by industrious labor, as soon as possible, beyond the necessity of federal support,” Mattson instructed farmers around Batesville on May 22, 1865.Footnote 3 On the transition to a free labor economy in the South, the Swedish veteran went on to claim that in the early years of reconstruction, the inhabitants of Arkansas generally “made fair contracts with the liberated slaves and strictly and carefully observed them.”Footnote 4 Yet, even if Mattson’s recollection is to be trusted, fair contracts carefully observed were not always the norm, and attempts to maintain an antebellum racial hierarchy were numerous.Footnote 5 Toward the end of his speech, Mattson’s memory allowed for as much as he related “one incident of many” that underscored the prevalence of “old slave thinking” in the post-war South.Footnote 6

“One day, a very tidy negro woman came and reported that her late master had recently killed her husband,” Mattson recalled. “I sent for the former master. He was a leading physician, a man of fine address and culture, who lived in an elegant mansion near the city. He sat down and told me the story, nearly word for word as the woman did.”Footnote 7 Mattson’s speech, as it has been preserved, recounted the incident as follows:

Tom, the negro, had been [the planter’s] body servant since both were children, and since his freedom still remained in the same service. Tom had a boy about eight years old. This boy had done some mischief and I (said the doctor) called him in and gave him a good flogging. Tom was outside and heard the boy scream, and after a while he pushed open the door and took the boy from me, telling me that I had whipped him enough. He brought the boy into his own cabin and then started for town. I took my gun and ran after him. When he saw me coming he started on a run, and I shot him, of course. [“]Wouldn’t you have done the same?” he asked me with an injured look. The killing of his negro for such an offense seemed so right and natural that he was perfectly astonished when I informed him that he would have to answer to the charge of murder before a military commission at Little Rock, where he was at once sent for trial.Footnote 8

Mattson, true to ideals about equality before the law, sided with the freedwoman; but his comment about her appearance, “a very tidy negro woman,” also showed preconceptions, common among white men, against freedpeople themselves.Footnote 9 Implicit in Mattson’s story was the fact that not all newly freed Black women were perceived as “very tidy.”Footnote 10 As such, the structure of Mattson’s 1889 address to local veterans reflected the fact that many Scandinavian immigrants immediately after the war were primarily concerned with economic betterment, personally and collectively, in a free market economy, but it also implicitly demonstrated the sense of white superiority that continued to inform life in the United States.Footnote 11 Less than a year before Mattson’s speech in Minnesota, two Swedish settlers in Texas, Carl and Fred Landelius, wrote to their sister Hanna in Sweden about cotton growth in Travis County and their belief in a racial hierarchy:

At the moment we are very busy with cotton picking. Naturally we cannot pick all our cotton but we have 5 negroes (and negresses) hired. Don’t you think that it would be strange to be where we are among so many foreign people? The negro is, I think, of the lowest race. His is very slow by nature, actually weak-willed [viljelös], and lives in the moment. Seldom does one see a negro who is well-off.Footnote 12

The roots of freedpeople’s poverty received little attention in the Scandinavian enclaves.Footnote 13 Neither did the associated paradox between free labor ideology and government redistribution of land to mainly white citizens, what Keri Leigh Merritt has deemed part of “the most comprehensive form of wealth redistribution” in American history.Footnote 14 But both free labor ideology and homestead policy were used as arguments for continued Republican support. To well-educated Scandinavian immigrants, equality was attained through free labor on one’s own land. The equality envisioned, however, was more economic than racial and social.Footnote 15

In the early years of reconstruction, there seemed to be clear limits to how far Scandinavian ethnic leaders could envision freedom and justice extending. It was, however, increasingly important for Scandinavian leaders to situate Norwegian, Swedish, and Danish immigrants positively in a postbellum national narrative where the effort to gain political influence only increased. Hans Mattson, for example, wrote specifically about Scandinavian immigrants’ love of liberty, Republican support, and zeal for Civil War service in his English-language memoirs.Footnote 16

Indeed, the experience of Civil War did seem to strengthen support for the Republican Party, not least its economic policy, among Scandinavian immigrants and thereby also strengthen ethnic leaders’ claim to political positions. On April 13, 1868, a brief front-page piece signed “many Scandinavians” appeared in the Chicago Tribune that touted Abraham Lincoln as “the representative and apostle of liberty to the downtrodden and oppressed of every nation on earth,” and it advocated, in essence, a Scandinavian ethnic holiday by “abstaining from ordinary work and festivities” on April 15.Footnote 17 The Tribune piece was one among numerous indications of Scandinavian support for the Republican Party – and its Civil War–era leaders – in the years immediately after 1865. Among the Civil War veterans, support was especially pronounced. On January 1, 1867, for example, a reunion for the 15th Wisconsin regiment was held at the hall of “The Republican Gymnastic Association” in Madison, with speeches praising the party in power.Footnote 18

In addition, Hemlandet on March 17, 1868, reported on “Grant Clubs” springing up “all across the country” and encouraged Swedes to attend meetings in Chicago’s 15th Ward.Footnote 19 Skandinaven on October 7, 1868, reported the organization of a “Scandinavian Grant Club” in Racine County among “the Scandinavians in the towns of Norway and Raymond,” in which everyone pledged to vote for the former Union general in the upcoming election.Footnote 20

Republican loyalty and military experience, in turn, offered post-war opportunities, and numerous ethnic leaders took advantage.Footnote 21 Hans Mattson was elected secretary of state for the Republican Party in Minnesota in 1869, Norwegian-born veteran Knute Nelson became a Republican state senator in Minnesota in 1874 and later a US senator, and his countryman and fellow veteran Hans B. Warner served as Wisconsin’s Republican secretary of state from 1878 to 1882.Footnote 22 Fritz Rasmussen, like Mattson, Nelson, Warner, and others, also continued his support for the Republican Party. Despite Rasmussen’s reluctance to serve in the military, and the health problems it later caused him, his wartime experience became a source of pride and a motivation for continued Republican allegiance. Thus, on a clear and pleasant morning, November 3, 1868, Fritz Rasmussen went down to New Denmark’s “townhouse” and gave his “Vote for the High – or General Election,” adding “this time it certainly was ‘electing a General,’ and a Grant too.”Footnote 23 In the following years, Rasmussen held several positions of trust in the community and regularly lauded American government principles for being “better, than any [that has] yet existed upon earth.”Footnote 24

In this sense, the Scandinavian experience mirrored that of the German veterans, Carl Schurz most prominent among them, who, in Mischa Honeck’s words, understood that “courage in combat and a noble role in victory were important bargaining chips” for “going into business or entering government service.”Footnote 25 Yet, contrary to German Republican leaders in 1868, among whom “radicalism was ascendant,” no forceful principled arguments for Black suffrage appeared in the Scandinavian public sphere.Footnote 26 Instead, Scandinavian immigrants who challenged the Scandinavian-American nonradical Republican orthodoxy during the early years of Reconstruction faced swift backlash.Footnote 27

While still in its infancy, socialist-inspired agitation among Scandinavian immigrants – embodied by the Norwegian-born 1848 revolutionary Marcus Thrane – appeared in the public sphere in 1866. In the opening issue of Marcus Thrane’s Norske Amerikaner (Marcus Thrane’s Norwegian American) on May 25, 1866, Thrane laid forward a “program” that argued for active engagement on behalf of fundamental human rights, not least “every man’s right to vote.”Footnote 28 Without explicitly connecting his editorial to freedmen’s right to vote, Thrane praised the principle of equality in the Declaration of Independence and argued that slavery had always been “inreconcilable with the Republican principle.”Footnote 29 Thrane also stressed women’s central role in the fight for these foundational human rights and tied it concretely to the abolitionist cause.Footnote 30

From Thrane’s perspective, among the most prominent “women and men” who had shaped public opinion against the antithesis of republican government, namely slavery, and helped save this basically “flawless” republican experiment from “failure,” was first and foremost Harriet Beecher Stowe. To Thrane, Stowe was followed by her younger brother Henry Ward Beecher, Charles Sumner, and Abraham Lincoln (“just mentioning his name makes the hearts beat”).Footnote 31

Thrane’s program – not least his implied socialist ideas (the present danger, Thrane wrote, “is the deep divide” between “wealth and poverty, enlightenment and ignorance”) and his fight for freedom, for Black people’s humanity, and for recognition of women’s central role in the public sphere – seemed increasingly important.Footnote 32 Enlightenment, according to Thrane, was the key issue, as it would ideally lead to the recognition of everyone’s equality regardless of skin color: “Could a Negro work as a carpenter?” Thrane asked and, pointing to the lack of social equality in the post-war North, answered, “There is scarcely a shop where a laborer would continue to work if a Negro should also work there.”Footnote 33 Change through enlightenment was needed, the editor argued.

Thrane’s ideas, however, also included critique of religion and caused enough concern among Scandinavian ethnic leaders that both Kirkelig Maanedstidende and Emigranten published an anonymous rebuttal titled “A warning for all Christians” against Thrane’s newspaper, despite its alleged small readership.Footnote 34 The letter, as well as the dissemination through the main religious and secular Scandinavian-American publications, testified to a sense of urgency in setting the agenda regarding notions of (economic) equality and morality – and, by extension, notions of American citizenship in post-war American society. In this sense, given Thrane’s admiration for Charles Sumner, the radical wing of the Republican Party received little, if any, support within Scandinavian publications.Footnote 35 Instead the Scandinavian editors’ policy positions aligned closely with those of the former Civil War general Benjamin Butler who, in 1869, addressed southern Republicans and stated: “Now you must help yourself.”Footnote 36 In other words, there could be no long-term governmental help for supporters of freedmen and freedwomen (e.g. opportunities for landownership or legal protection in contractual disputes) in the racialized post-war free market economy.Footnote 37

Among Scandinavian immigrants, not least editors and clergymen, there was little urge to use the Civil War as a stepping-stone to reinvent and extend citizenship rights to the formerly enslaved and to women. Instead, the Scandinavian-American press and clergy devoted space to a multitude of other issues, not least whether slavery was inherently sinful. By debating “last year’s war,” the Scandinavian-born elite essentially made it more difficult to start a conversation about future struggles over the meaning of equality and citizenship.

Any lingering doubt about whether Old World elites, as represented by Old World state churches, attempted to wield a conservative influence over Scandinavian communities in the New World vanished after the Civil War. Marcus Thrane’s Norske Amerikaner, as Terje Leiren has shown, “survived only four months, largely because Thrane’s social and anticlerical views precipitated a bitter feud with the clergy and its supporters.”Footnote 38 Similarly, the 15th Wisconsin regiment’s former chaplain, Claus Clausen, was essentially forced out of the Norwegian Synod when discussions over slavery’s sinfulness erupted anew.Footnote 39

This schism within the Norwegian community had been evident since 1861, when Claus Clausen retracted his statement that slavery was not “in and of itself a sin,” and it reemerged after July 4, 1864, when J. A. Johnson, who had been instrumental in raising the 15th Wisconsin Regiment, sided with the regiment’s former chaplain.Footnote 40 By 1865, the Synod leadership was publicly known to view Clausen’s interpretation as “diabolical” and rejected attempts to compromise.Footnote 41

Throughout the 1860s, the slavery debate raged between conservative Norwegian Synod clergymen with ties to education in the Old World state church and Claus Clausen’s faction who generally stuck to the 1861 statement that slavery was indeed sinful.Footnote 42 While the Norwegian Synod seemingly won the theological debate, Claus Clausen won considerable support in Scandinavian-American communities as well. Skandinaven, for example, pointed to Clausen’s popularity in 1867. During a visit to Chicago, Clausen had attracted one of the “largest gathering of Skandinavians [sic] that has ever attended a religious service in America,” Skandinaven reported on January 31, 1867:

It is probably especially of the strife and optimism he has shown in regard to slavery as a debatable question within the Lutheran Church that he has come to the front, so to speak, for the public and, not least, because of the harsh unforgiveable and unchristian judgement his enemies have spread against him that he [to a great extent], receives the sympathy and is held in high esteem by the public. The following Sunday morning he preached in Vor Frelsers Kirke [Church of Our Savior] in Chicago, again for an overflowing audience.Footnote 43

The extent to which Skandinaven actually spoke for a Scandinavian “public” is difficult to assess, but the account is supported by a correspondent, identified as a former schoolteacher from Hedemarken in Norway, who wrote home from Primrose, Wisconsin, on February 4, 1868. In his description of the religious conflict, the writer stated that the people had “demonstrated common sense and distanced themselves from the clergy’s arguments.”Footnote 44 Only pastor Claus Clausen, according to the letter writer, represented “defense of truth and freedom.”Footnote 45

This postbellum slavery debate in the Norwegian Synod, and its leadership’s insistence that slavery “in and of itself” was not sinful, was one of several examples of racial conservatism among Scandinavian-born opinion makers and helped legitimize opposition to equality and thereby citizenship rights for nonwhites.Footnote 46 In post-emancipation Scandinavian and American society, the view that white men of Nordic heritage were naturally superior to other ethnic groups, not least Black people previously held in bondage and American Indians, was common and, as we have seen, had found alleged religious and “scientific” support in the Old World for more than a century.Footnote 47

Whether through religion or “science,” these racist views were regularly on display in the Scandinavian-American public sphere, and the connection between Scandinavian religious conservatism and reluctance to embrace nonwhites as equal citizens in the United States was made clear in opinion pieces such as the one that appeared in Emigranten on March 16, 1868 linking interpretations of the Bible to racial superiority.

Figure 12.2 Claus Clausen maintained his theological anti-slavery conviction after the Civil War and was consequently thrown out of the Norwegian Synod, again.

In a piece titled, “Is the Negro an animal or does he have a soul?” an admitted Democrat argued that the differences between white and Black people were so great that the latter could not possibly be a descendent of Adam, whom God had breathed life into, and went on to say that if “the Negro was in [Noah’s] ark (and we believe he was there), he entered as an animal and is an animal to this day.” Moreover, the Norwegian-born writer argued that any mixing of the Black and white race would categorize the offspring as Black and “therefore we believe that only Adam and his descendants have souls and that Negroes are not descendants of Adam.”Footnote 48

This line of argument resonated with Emigranten’s editor, who noted that this opinion had been sent to him by an “esteemed” fellow Norwegian and that it did not seem to make sense to do missionary work among people of African descent, for if Black people were just “soulless donkeys or, at best, enlightened mules, then it is after all too much to make them Christian.”Footnote 49

Clausen, on the other hand, continued to stress a greater sense of equality (“no Christian could be pro-slavery”) and resigned from the Norwegian Synod on June 28, 1868, when its leadership insisted on different theological interpretations.Footnote 50 Along with Clausen, “a dozen or more congregations of the Synod similarly broke away or were split in two.”Footnote 51 The Synod, with some merit, accused Clausen of holding theologically inconsistent views in a lengthy account published in 1868.Footnote 52 Clausen’s eighty-six-page rebuttal reiterated his anti-slavery position and contained unmistakable references to Grundtvig before he “laid down his pen.”Footnote 53

With failing health, partly due to his Civil War service, Clausen instead set his sights on landownership in the South and helped spearhead an ill-fated immigrant colony scheme in Virginia.Footnote 54 The colony was partly doomed by the financial crisis of 1873 but did exemplify Scandinavian immigrants’ continued preoccupation with land in the post-war years. Most Norwegians, Swedes, and Danes, however, set their sights west.

Exemplifying Scandinavian immigrant concern with social mobility through landownership and an expanding American empire on the continent, Danish-born Laurence Grönlund, whose writings in time would inspire Edward Bellamy and Eugene Debs, published a piece on the Homestead Act in Fremad (Forward) on April 23, 1868, shortly after his arrival to the United States.Footnote 55

Grönlund criticized American politicians for being too focused on “corporations and monopolies” at the expense of the “great mass which produce what the legislators consume.”Footnote 56 One notable exemption to the pattern, “an oasis in the desert,” was the Homestead Act, which Grönlund a few weeks later called a politically mandated leveller that allowed poor Old World immigrants to finally enjoy “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”Footnote 57 Impressed with the speed by which “liberal ideas” had spread in the United States to protect poor people against the powerful, Grönlund argued that the nation’s moral character had been elevated, as the people could now enjoy the fruits of their own labor by “sitting under one’s own grapewine and fig tree.”Footnote 58 To Grönlund, landownership yielded an almost “holy satisfaction.”Footnote 59 What is “life worth,” Grönlund asked, “if robbed of all convenience and comfort to the point where life consists of misery, degradation, and poverty”?Footnote 60 Entirely missing from Grönlund’s lengthy texts, however, were questions of Native people’s religious connection, and right, to the land. Such omissions, conscious or not, continued among Scandinavians for decades and helped settlers justify land appropriation.Footnote 61

To a greater degree than other foreign-born groups such as the German and Irish, Scandinavian immigrants settled predominantly in rural areas (see Figure 12.3).Footnote 62 For this reason, the Homestead Act, predicated on population growth and territorial expansion, was central to Scandinavian immigrants’ visions of an American self-sufficient, moral citizenship and remained so for years. Conversely, high-level political attempts at territorial expansion into the Caribbean, where few Norwegian, Swedish, or Danish farmers imagined themselves settling, received much less attention.

Figure 12.3 “Norsk Hotel” (Norwegian hotel) reads the sign above the entrance where four unidentified people are standing in an otherwise rural Iowa setting. The photo thereby exemplifies Norwegian immigrants’ continued attachment to Old World language and culture in rural America, what Jon Gjerde has called “complementary identity.”

To Scandinavian settlers, and many Americans, a contiguous American empire was the aim. Scandinavian immigrants’ support was of such scale that “several questions” regarding the Homestead Act arrived at the Skandinaven offices in Wisconsin within just one week in 1868. The queries prompted Skandinaven’s editors, who knew that this law was one of the “most important for the Norwegian settlers,” to, once again, publish answers to these frequently asked questions.Footnote 63

Notably, Scandinavian immigrants after the Civil War started casting their gaze even further west. A Norwegian-born settler wrote from Minnesota in early 1868 that “3 ½ years ago there was not a white man in sight. Wild Indians and deer were the only living creatures,” but now numerous Norwegian, Swedish, and American settlements were part of the immediate surroundings.Footnote 64 Just a few months later, the Swedish-born pastor Sven Gustaf Larson relayed news of a small but increasing Swedish community in Jewell County, Kansas, where more than twenty-five countrymen each had laid claim to 160 homestead acres. As an indication of these Scandinavian settlers’ mindset, Larson recounted a conversation with the land commissioner in Junction City who had promised that there would be enough Homestead land for half of Sweden, to which the pastor in his letter to Hemlandet remarked, “Why not say all of Sweden’s population if one takes Nebraska and other western states into consideration.”Footnote 65 That the remaining valuable Native land in Kansas would soon be available for purchase “for the usual government price” was taken for granted by Larson in a subsequent dispatch.Footnote 66 The same argument – free land formerly inhabited by American Indians, soon to be available through the Homestead Act or for sale at $1.25 an acre – appeared time and again in the Scandinavian-American texts.Footnote 67

As far back as 1838, Ole Rynning had noted how “the Indians have now been moved far west away from” the borders of Illinois, and by early 1869 a Swedish correspondent reported home about potential landtaking on “[so-called] Osage-Indian land” in southern Kansas but warned against taking land in western Kansas “as long as the bloodthirsty Indians there frequently make their greetings.”Footnote 68

Further north, despite an anonymous correspondent in 1864 imploring Fædrelandet’s readers to recognize the immense “suffering” inflicted on Native people following their removal from Minnesota, the dispossession continued in the Dakotas.Footnote 69 Karen V. Hansen explains:

These lands in the public domain of the United States had recently been ceded by Indian peoples negotiating as sovereign powers. From the perspective of American Indians, therefore, the Homestead Act amounted to a wholesale scheme for further encroachment, violating the terms of the treaties they had recently signed protecting their land. In reaction to the continuing advance by white settlers, Dakota Chief Waanatan, attending a peace commision in July 1868, said, “I see them swarming all over my country … Take all the white and your soldiers away and all will be well.”Footnote 70

Despite Chief Waanatan’s plea, white settlers, Scandinavians among them, continued to move onto American Indian land and within decades came to occupy much of the land around Spirit Lake that had otherwise been set aside for Dakota bands following the 1862 war in Minnesota.Footnote 71 White supremacy was, as Barbara Fields reminds us, “a set of political programs,” among other things, and the Homestead Act, with its requirement for citizenship or stated intent to naturalize, was one such example.Footnote 72 Many Scandinavian-Americans saw landownership or opportunities for upward social mobility, along with political participation, as a right that came along with their understanding of American citizenship.Footnote 73 In the process, Scandinavian immigrants often supported a social hierarchy where American Indians and nonwhite people were deemed inferior. Still, in 1864, Fædrelandet’s anonymous correspondent described Native people in the Dakota territory as “sick, naked, about to die of hunger, and defenseless”; and several descriptions of “suffering poor” freedpeople, who, in Frederick Douglass’ words, were “literally turned loose, naked, hungry, and destitute, to the open sky” after the Civil War, also appeared in the Scandinavian-American public sphere.Footnote 74 Initiatives to help alleviate nonwhite poverty, organized by Scandinavian-born immigrants, however, remained rare. Instead, Scandinavian community leaders, when advocating economic assistance to groups in precarious circumstances, prioritized resources to local Scandinavian-American aid societies or collections on behalf of Old World communities suffering from starvation or deep poverty.

While Scandinavian immigrants generally subscribed to the “free labor” ideology underlying their idea of “liberty and equality,” these ethnic mutual aid initiatives also testified to immigrants’ awareness of the market revolution’s potential fallibility.Footnote 75 White skin, a Protestant upbringing, and a relatively high educational level due to Old World compulsory education enabled many Scandinavian immigrants to steer clear of the most “exploitative class relationships,” but hard work did not always yield economic success.Footnote 76

This realization had, in part, led three Scandinavians in New York to form an association in the summer of 1844 to socialize and provide help in case a fellow countryman fell on hard times.Footnote 77 This Scandinavian Association established in a small house on Cherry Street on Manhattan’s Lower East Side had the added purpose, according to a later travel writer, of bringing Scandinavians together to counterbalance “German, Irish, and all the other foreign nations who already have societies here.”Footnote 78 The Scandinavian Association’s minutes – and its underlying mutual aid idea, which inspired similar associations in the Midwest – was a reminder that Norwegian, Swedish, and Danish immigrants regularly needed a helping hand to stay afloat in the American labor market.Footnote 79

Scandinavian immigrants in Wisconsin and Illinois also set up several mutual aid societies in 1868 as hunger in Norway became a factor that increasingly pushed people in the Old World toward the Midwest. The Swedish association Swea and “the Emigrant Aid Association” worked both separately and collaboratively to establish a shelter in Chicago.Footnote 80 Moreover, John A. Johnson in Wisconsin organized a collection of funds for needy immigrants to be sent to Fædrelandet’s editor or distributed through aid societies and pastors in Chicago or Milwaukee.Footnote 81

The Scandinavian immigrant elite, however, who specifically advocated American landownership as a means for achieving equality and liberty when leaving the Old World, were conspicuously silent on the topic of land- (and by extension wealth-) redistribution in the wake of the Civil War and by 1868 were more interested in white ethnic economic issues than in national aid initiatives on behalf of nonwhites. In short, Scandinavian-Americans in the post-war moment proved more interested in organizing help for their former fellow citizens from the Old World than they were in helping American Indians, on whose lands they often settled, or in helping the newly emancipated, and soon to be fellow, American citizens navigate the structural pitfalls of a free labor economy.Footnote 82

By 1868 the work to ensure political and civil rights for freedpeople seemed finished in the eyes of the Scandinavian-American editors. The former Confederate States were slowly adopting the rewritten Constitution that formally ended slavery within the United States, and now financial matters could again occupy the minds and newspaper pages in Scandinavian communities. The economic opportunities that had led the Civil War–era Scandinavian immigrants to the United States in the first place were now to be utilized, Homestead Act in hand, with freedpeople’s and American Indians’ rights taking a back seat to the renewed focus on agricultural and industrial growth.

Yet, even as Scandinavian-American communities pushed issues of reconstruction into the background, continued discussions over citizenship rights in Washington, DC, turned out to have important implications for the attainment of contiguous and noncontiguous American empire

“The harbour is a great basin, capacious enough for a small navy; and its entrance, though safe and easy, is through a narrow strait, which even the diminutive forts and antiquated ordnance of the Danes are able to defend.”Footnote 1 Thus wrote William Seward’s son Frederick, alluding to the fact that the secretary of state’s 1866 trip to the Caribbean had a dual purpose, part recuperation and part reconnaissance. To achieve an American toehold in the Caribbean, Seward, travelling on the steamer USS De Soto, had decided to dip his own toe in first. When the Seward family arrived at St. Thomas on January 9, 1866, they found conditions favorable, though dated, for strategic and economic purposes. “It has as peculiar advantages for a naval station as it has for commercial support,” Frederic Seward wrote.Footnote 2 From an American perspective, it was lucky that this island had fallen into Denmark’s “possession” as the Northern European nation was “strong enough to keep it, but not aggressive enough to use it as a base for warfare.”Footnote 3 By 1866, however, Denmark was in decline, and the islands’ revitalization through American strength and energy, Seward believed, would be an advantage for all involved.Footnote 4 After his personal inspection and visit to other Caribbean localities, Seward was therefore well-prepared to make a concrete offer when he returned to the United States on January 28, 1866.Footnote 5 Equally importantly, Danish politicians were willing to listen.

American strength and Danish weakness, along with timing, were key variables as the negotiations moved forward. By the late summer of 1865, Seward had recovered enough from the April assassination attempt to resume negotiations, and Raaslöff, realizing Denmark’s Kleinstaat status, kept advising Danish politicians to engage in negotiations.Footnote 6 Raaslöff by late 1865 acknowledged that the domestic situation in the United States was deteriorating but nonetheless said he “expected that there would be considerable patriotic support for a policy of strengthening the country militarily and strategically through annexation of the Danish islands.”Footnote 7 Raaslöff’s initial optimism was not unfounded. The American government, authorized by President Lincoln, had initiated negotiations, Seward was personally invested, and the American secretary of the navy, Gideon Welles, during the Civil War described St. Thomas as a potentially “desirable acquisition as a coaling station and central point in the West Indies.”Footnote 8

However, by March 30, 1866, Welles was already starting to think more critically about spending millions of dollars on an island group that could, essentially, just be taken by force:

Mr. Seward brought up in the Cabinet to-day, the subject of the purchase of the Danish islands in the West Indies, particularly St. Thomas … He proposes to offer ten millions for all the Danish islands. I think it a large sum. At least double what I would have offered when the islands were wanted, and three times as much as I am willing the Government should give now. In fact I doubt if Congress would purchase for three millions, and I must see Seward and tell him my opinion.Footnote 9

In the preceding months, however, Raaslöff was assured that the American interest remained intact. Through dinner parties with Assistant Secretary of the Navy Gustavus Vasa Fox (at which Raaslöff also urged the US government to resume Caribbean slave patrols and revive the 1862 colonization agreement) Raaslöff got a feel for the American political climate, and a Danish cabinet change moved the negotiations concretely forward.Footnote 10 On November 6, 1865, the large Danish landholder Count Christian E. Frijs assumed power and worked closely with Raaslöff on foreign policy hereafter.Footnote 11 By December 1865 Raaslöff could finally notify the American government that Denmark was ready to sell St. Thomas, St. Croix, and St. John if the price was right.Footnote 12

Finding the right time and the right price, however, proved challenging. William Seward’s return to political life in 1865 saw him increasingly tied to Abraham Lincoln’s successor, Andrew Johnson; though the new president generally supported expansion into the Caribbean, he also urged that “negotiations rest a short while” to avoid a too direct connection, in the public’s eye, between Seward’s St. Thomas visit and concrete discussions.Footnote 13 Moreover, Johnson was becoming increasingly involved in a struggle over Abraham Lincoln’s legacy with the Republican-controlled Congress after it convened in December 1865.Footnote 14

Raaslöff, who stressed that Denmark needed a sizable offer to overcome domestic diplomatic doubts about the sale, reported home on February 8, 1866, that he had suggested $20 million as a minimum amount.Footnote 15 But crucial leverage was missing. As Erik Overgaard Pedersen has noted, “Danish possession of the islands had become insecure,” and if the United States, England, or France went to war there was a sense that the islands might well be taken by force.Footnote 16 American negotiators shared the same view.

After several months of meetings between Raaslöff and Seward, the latter, on July 17, 1866, finally offered a concrete sum of $5 million, which was in line with American military officers’ assessments. Brevet Major-General Richard Delafield took Denmark’s vulnerable geostrategic position into account when stating that $5 million would be more than the Danish government could expect by “holding a prize that can be taken from him at any moment he become at war with a strong maritime nation.”Footnote 17

Between Seward’s and Raaslöff’s conversation in early 1865 and 1868, the prospect of a Danish-American treaty for the sale and purchase of St. Thomas, St. John, and possibly the agriculturally based island of St. Croix waxed and waned, but talks were generally considered promising by both parties.Footnote 18 Yet, as Pedersen has succinctly noted, the negotiations hinged on balancing domestic and international politics on both sides of the Atlantic.