Book contents

- The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Child Development

- Child Development

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Contributors

- Editorial preface

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments: External Reviewers

- Introduction Study of child development: an interdisciplinary enterprise

- Part I Theories of development

- Part II Methods in child development research

- Part III Prenatal development and the newborn

- Part IV Perceptual and cognitive development

- Attention

- Audition

- Biological motion perception

- Cognitive development during infancy

- Cognitive development beyond infancy

- Executive functions

- Face perception and recognition

- Imitation

- Intelligence

- Memory

- Multisensory development

- Olfaction and gustation

- Perceptual-motor calibration and space perception

- Sleep and cognitive development

- Vision

- Part V Language and communication development

- Part VI Social and emotional development

- Part VII Motor and related development

- Part VIII Postnatal brain development

- Part IX Developmental pathology

- Part X Crossing the borders

- Part XI Speculations about future directions

- Book part

- Author Index

- Subject Index

- Plate Section (PDF Only)

- References

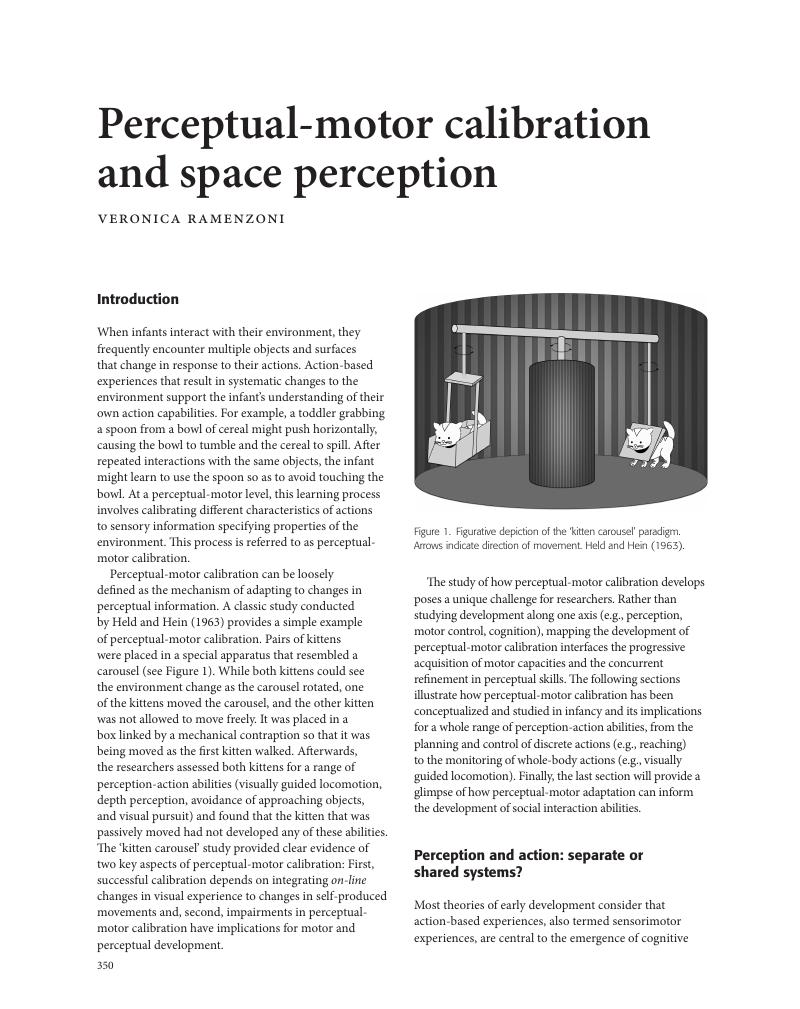

Perceptual-motor calibration and space perception

from Part IV - Perceptual and cognitive development

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 26 October 2017

- The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Child Development

- Child Development

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Contributors

- Editorial preface

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments: External Reviewers

- Introduction Study of child development: an interdisciplinary enterprise

- Part I Theories of development

- Part II Methods in child development research

- Part III Prenatal development and the newborn

- Part IV Perceptual and cognitive development

- Attention

- Audition

- Biological motion perception

- Cognitive development during infancy

- Cognitive development beyond infancy

- Executive functions

- Face perception and recognition

- Imitation

- Intelligence

- Memory

- Multisensory development

- Olfaction and gustation

- Perceptual-motor calibration and space perception

- Sleep and cognitive development

- Vision

- Part V Language and communication development

- Part VI Social and emotional development

- Part VII Motor and related development

- Part VIII Postnatal brain development

- Part IX Developmental pathology

- Part X Crossing the borders

- Part XI Speculations about future directions

- Book part

- Author Index

- Subject Index

- Plate Section (PDF Only)

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Child Development , pp. 350 - 357Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2017